By William R. Hogan

On August 4, 1944, a Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress heavy bomber, tail number 43-37909, so new that it did not have a nickname or nose art yet, took off from England on a bombing run over Germany that would end in a crash landing on Borkum Island in the North Sea.

After taking ground fire, the pilot and co-pilot, Lieutenants Harvey Walthall of Virginia and William Meyers of Pennsylvania, heroically recovered their stricken aircraft to safely land on a pebble beach on the German island of Borkum. A mob of locals roused by nearby Nazi officials beat and abused the prisoners of war on what turned out to be a death march.

It was a balmy morning in Sudbury, England, and the sun peeked over heather fields of gold and stone gray manor houses of the Salisbury plain. The crews of the 486th Bombardment Group (Heavy) plodded through their mission briefing while crews fed guns heavy belts of .50-caliber ammunition, checked hydraulics and finished loading bombs.

It was only this B-17G crew’s third mission together. The 486th Bombardment Group’s primary target that day was the Ernst Schliemann oil refinery in Hamburg. Its 5,000-ton per month capacity was vital to the Wehrmacht’s mechanized armies.

In the nose below the flight deck sat Lieutenant Quentin Ingerson, navigator. He checked the routes on maps, reviewing air assembly areas and the dreaded red fans of expected Luftwaffe fighter coverage. He was the youngest member of the crew at only 19.

Immediately behind the pilots was Sergeant Kazmer Rachak, 22. When the war started, he dreamed of becoming a pilot but failed the flight physical because of color blindness. He requested to serve in the Air Corps and was trained as the flight engineer/gunner. His job was to fix anything that went mechanically wrong in flight.

A long hop over the bomb bay into the middle fuselage reached radio operator Sergeant Ken Faber’s station, where the 26-year-old New Yorker ran checks on the four radios and internal communications suite under his charge. A sheet metal worker before the war, Faber was devoted to wife Justine, waiting for him back home in Eerie, New York.

The ball turret aft of Faber’s position housed Sergeant James W. Danno, 21, from Washington. This was the former theology student’s first combat mission.

Sergeant William Dold sat astride the two large windows, each with a swiveling .50-caliber machine gun facing port and starboard on the B-17’s “waist.” He was attending the University of Notre Dame when the war geared up and volunteered to get a chance at being a pilot. An Army physical put an end to his dream of piloting due to “unsteady hands.”

The last man to clamber aboard was Sergeant William Lambertus, 25. The tall blonde-haired William grew up in Newark, New Jersey. His job was to protect the B-17’s six o’clock position. For this task he manned dual .50-caliber machine guns poking menacingly through an armored glass bubble in the plane’s tail.

Harvey Walthall called out, “Left engine starter on!” The first of four powerful radial engines coughed to life, propellers spinning. Bill Meyers followed with the second as the pilots sequentially engaged Left 1, Left 2, Right 3 and Right 4 engines from the rack of throttles crammed between them. English heather still newly grown swayed low against the hurricane force winds of 20 B-17s cranking their engines.

Facing the runway at full throttle, Harvey nodded at Bill as the brakes were released and their Flying Fortress rolled down the tarmac at 100 mph. The bomber picked up maximum speed, and the pilots felt the heavy burden of 4,800 pounds of high explosive bombs shift from the pneumatic tires and ease up to the wings as lift took over.

At 5,000 feet, according to plan, they reached the assembly altitude at 9:40 a.m., where the rest of the wing was waiting. At 12,000 feet, the second wing of 20 planes of the 486th Bombardment Group completed the 40-plane formation, moving purposefully northeastward like a metallic storm cloud.

At 12:45, Walthall called out over the internal communications: “Fighter escort is on station.” Five minutes later: “Enemy coastline crossed.” The formation continued, hugging the Dutch coast further over the North Sea toward Germany. Occasional radio transmissions broke the monotony.

Forty minutes later, they entered the most dangerous portion of the flight as the bomber formation took a straight course, no longer zigzagging. The statistically safest bet, the pilots were told, was the shortest, most direct route through flak barrages. This also kept the formation tight to protect from enemy fighters and helped ensure accurate bombs on target.

Black pluffs of exploding flak bloomed ahead. Bomber 909 in the rear of the formation trudged on. The explosions and turbulence grew closer and shook the plane’s frame as well as the crew’s nerves.

A dozen tense minutes of bumpy flight passed. Pilot and copilot began to think they would all make it through to the bombing run when they felt a shudder and strong surge through the yoke.

A burst of flak had detonated directly below the bomber, sending a compressed wave of hot air through the fuselage and into the hydraulic system that operated the moving parts of the wings. The bomber rose 200 feet within two seconds, dangerously close to the bomber above, number 145.

Rachak saw it all from his cupola on top of the fuselage. Number 145 approached fast toward their starboard wing. Its tail section drifted down toward 909’s No. 3 and 4 engines. The propellers of 909 cut into the empennage of 145 between the waist and tail guns with a sickening roar and crunch. Debris shot out at all angles, hitting the fuselage with a force like shrapnel exploding within 50 meters of the aircraft. Then, the horizontal stabilizer came down on the top turret.

Kazmer was knocked to the flight deck as the turret dome crumpled and shattered. Freezing air shot in, adding to the noise inside the cabin. Off to 909’s right, the tail of 145 held tight in spite of the deep gashes that threatened to cause the ship to come apart. Pulling out of the formation, 145’s pilot, Lt. William Dale, kept her level but her bombing run was finished. It would be all Dale and the crew could do to get themselves safely back to friendly territory.

In the cockpit of 909, Meyers and Walthall saw that the engines ran but with damaged blades. The big bomber dropped heavily to the right with a moan of creaking metal. Alarms sounded in stressed out, mechanical whines. The bomber drifted right in an “S” turn that threatened to invert them. Inside the cockpit, the altitude gauge spun as the aircraft fell. Walthall scrambled to take control of the plane and get it out of its backward death spin. He issued crisp orders to the navigator to mark their position and send a May-Day on the squadron net.

Next, he added power to engines 3 and 4, then pulled on the yoke to keep the stricken bomber from a complete stall. The aircraft continued to dive into a bank of clouds. Crews in aircraft above lost sight as their undamaged machines continued on at 500 mph.

Behind the pilots, Kazmer thought he heard the order to bail out over the terrible wind noise. He checked his parachute harness, then looked toward the main access door. Ingerson also thought he heard the bail out order. According to procedure, Kazmer would be the first one out followed by the navigator. Kazmar unstrapped his bulked up body from his seat then rapidly waddled to the already open door. A couple more steps and Kazmer was sucked out violently from the waist access door. His body was tossed about in the rough air like a leaf in a wind gust until a bone-jerking stop let him know his parachute had opened. Ingerson followed close behind from his own access door, greeting the open sky and blooming parachute canopy a few seconds later.

Both crewmen drifted slowly away through the low bank of clouds as their brothers remained at their stations, unaware that the two had bailed out. Any thought of the remaining crew bailing out was impossible due to the falling plane’s G forces.

Back inside the cockpit, Walthall and Meyers’ calm efforts to increase power to the stricken engines paid off. At 10,000 feet both could feel the familiar and comforting pressure on their palms and feet pushing back from the pedals and yoke as 909 generated enough lift on her right side to stop the spinning elevation dial and regain a horizontal attitude.

Once out of the bank of clouds, the pilots realized they would not be making it back to England or even France. They had lost a lot of altitude, and the engines could not generate enough power to stop their descent. The crippled bomber whined and shook in a steady descent that appeared to clear them from the narrow channel between the mainland and a large island offshore.

That ground surged toward them. There was a lighthouse and small town on the far side of the strip of land. Walthall saw what looked like a naval base and the menacing skyward pointing barrels of an antiaircraft battery.

Then 909 gave its last effort, its frame shaking roughly, smoke pouring out of the No. 3 engine. “Crew: Brace for Impact.” At 20 feet above the ground there was a split second of quiet as Meyers cut the long-suffering engines. Then a sickening crunch and impossibly loud grinding of rock on aluminum were heard. The shock jolted the crew in the mid-section.

After 30 long seconds, the bomber stopped; an 800-foot gash cut the beach behind it. Everyone let out a sigh of relief and sat back to collect their thoughts. Meyers and Walthall had pulled off an impossible save of their bomber and crew. But their ordeal was just beginning.

As they exited their aircraft in relief, the seven flyers saw armed German naval personnel rush forward, rifles at port arms. Shouts of “Hande hoch!” preceded prods with rifle barrel or butt. The seven airmen staggered outside their stricken aircraft. The Germans shoved them along until the Americans stood in line, dazed and panting.

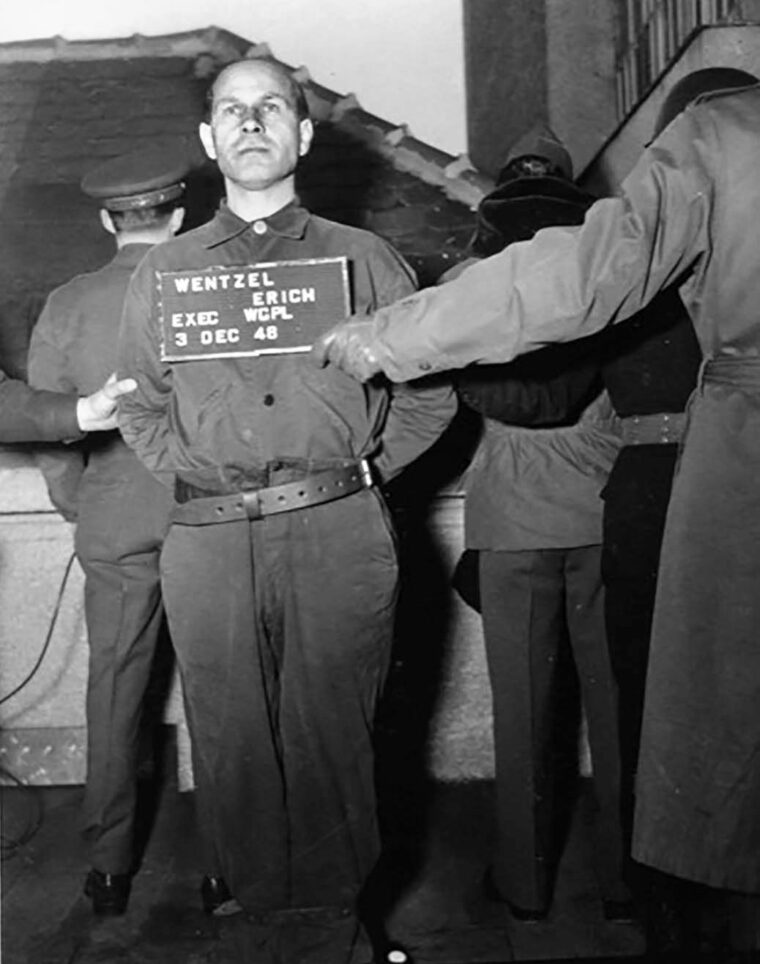

Finally, an English-speaking man in German naval uniform marched up and quieted down the others. He introduced himself as Navy Lieutenant Erich Wentzel and informed the fliers that they were now German prisoners of war.

Wentzel conducted a rude interrogation of each U.S. flyer, writing down notes as he went down the line one by one. He then assigned two sergeants, Schmitz and Wittmaack, to march the prisoners through the center of the island. The route of march took them past Reich Labor Service (RAD) men clearly visible turning shovels down the road.

The disheveled, exhausted airmen trudged forward toward the end of the gray, dark beach, the rhythmic crunch of boots on gravel, heavy breathing, and grunts from the guards the only sounds for the next 10 minutes.

Ahead was the RAD work gang, eight men in gray overalls, assorted hats and sleeves rolled up showing sinewy arms that folded spades over their shoulders. The workers assembled into lines on each side of the gravel road.

The U.S. flyers began running the gauntlet of shovel wielding RAD diggers. Blows with shovel, fist or foot greeted the prisoners. German shouts melded with grunts and exhalations of pain from the fliers. Howard Graham shuffled in, his heavy pants slowing him despite the pushing from behind and the sides. The RAD workers tired themselves swinging spades and reverted to throwing punches in the close quarters of the 16-man scrum.

The Americans in front turned around to help the others. Sergeant Schmitz rudely pushed them on. The fliers could not catch their breath; the guards prodded on, making them hold their trembling, bruised arms over their heads. They had another 6.5 miles to go to the port in the building heat of midday.

The Americans in front turned around to help the others. Sergeant Schmitz rudely pushed them on. The fliers could not catch their breath; the guards prodded on, making them hold their trembling, bruised arms over their heads. They had another 6.5 miles to go to the port in the building heat of midday.

Meanwhile, the naval commander, Captain Kurt Goebbel, rang Borkum’s mayor, Jan Akkerman, informing him that the giant bomber that everyone in town saw and heard as it careened overhead had crash landed on the empty northern beach and that seven “Ami” prisoners were to be marched to the southern pier. The naval officer added ominously: “This is a purely military matter and I hope civilian authorities will not intervene as you may have read in Reich Propaganda Minister Goebbels’ treatise on dealing with these war criminals.”

Akkerman was a virulent Nazi, a member of the party since 1934, and continued to believe in the false promise of that ideology. He was familiar with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels’ pronouncement that Allied aviators were war criminals and deserved the most savage treatment possible.

He looked out his window on the second floor of the town hall toward the small main square. People were milling about as word had already spread that the bomber’s crew were in German hands and would likely march through town to get to the naval pier. Akkerman hung up the phone, bent on revenge.

The seven crewmen and guards marched for 30 minutes. It was a warm day, and the bomber crew breathed heavily out of parched, dry mouths. The road changed from narrow gravel to an improved two-lane asphalt avenue headed straight to a jumble of small buildings in the island’s town.

Graham’s guard, Karl Geyer, called out to Wentzel to stop the column so that the young flyer could adjust his heavy trousers. Wentzel sharply denied the guard’s request, then threatened to punish Geyer if he allowed his American prisoner to drop his hands again.

Ahead, the small town was now in view with streets leading to a row of two- and three- story brick buildings centered around a cobblestoned open area. At the center stood an imposing five-story brick building crowned by steeples and a spire. Several dozen people assembled in two masses on each side of the street.

Another guard, a young Austrian named Johann Pointner, called a halt. Shouldn’t the column turn on Victoria Street and avoid the mob ahead? It was the shorter way to the port. Wentzel, mounted on a bicycle, pulled up to the group and ordered the formation on through the center of town and the angry mob.

In front of the Borkum City Hall, Mayor Akkerman riled up the townspeople. After his phone call, he strode flamboyantly out of his office to address the crowd. Adopting his best Hitleresque gesticulation complete with rabidly escalating speech, Akkerman enjoined, “The bomber you saw crash land on the beach north of here has yielded seven prisoners, seven war criminals! They are marching here at this moment. Now is the time to pay them back for their terror raids upon our people.”

Initially curious, the crowd quickly turned into a mob as people began to incite violence.

“Beat the dogs, the murderers!” shouted Akkerman, his face contorted with rage.

Slowly, inexorably, the seven were pushed and prodded toward the waiting mob. They entered the town square, and chaos ensued.

Some civilians attacked the prisoners, while other egged on shouting: “Knock them down, kill them, they kill our wives, brothers and children.” A flurry of insults and spittle followed. A fist flew in, connecting with an eye socket. Slaps to the back of the head echoed with dull thuds.

As the aviators stumbled on through the corridor of angry villagers, an air raid policeman, Gustav Mammenga, rushed up, delivering a brutal blow to Graham’s head. Graham collapsed in a heap. The column slowed under the attack.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, German Army Private Erich Langer sprang forward after making his way out of the crowd. The crazed soldier was on leave after his entire family had succumbed weeks earlier to an Allied bombing raid over Hamburg. “You damned swine! You murdered my wife and four children!” he bellowed.

Langer drew a pistol from a black leather holster, fiery hate in his eyes, and shot the supine Graham. The loud bang hushed and froze the crowd. The convoy of prisoners halted briefly, then Schmitz and Wittmaack ordered them on. Several civilians ran away from the mob, not wanting any part in what was sure to follow.

Graham lay on the ground on his side convulsing as blood poured from his chest. Several villagers ran to him, not to abuse him but to move him into a nearby office to try and stop the bleeding. Graham was fading. A wild-eyed Langer burst into the office, waving his pistol and offering a “mercy shot.” A German secretary yelled at Langer to get out, but Graham soon died. Langer followed the prisoners down the cobblestone street leading out of Borkum.

The surviving Americans yelled and cursed at their guards. Schmitz and Wittmaack, fearing they were losing control, ordered the guards to use their rifle butts on the prisoners. The march continued to the outskirts of town and back to the countryside. The ground began to slope to the coastline. The group was getting close to the seaport where a waiting ferry promised deliverance.

Behind the formation came the angry shouting of murderous Erich Langer. He caught up to the shuffling formation and began yelling in staccato German at Schmitz and Wittmaack. The arguing went on for several minutes.

The Germans could not leave any witnesses to Graham’s murder. They lined up the exhausted prisoners next to a tree line. The damp smell of salt and sea reminding them they were close to the seaport. But there was nowhere to run.

Langer, Schmitz, and Wittmaack walked down the line firing their weapons. The thud of a falling body followed each bang. For Harvey Walthall, William Meyers, William Dold, William Lambertus, and James Danno, the war ended on the soggy ground of Borkum Island in a blinding pistol shot.

The war roared on for almost another year. Finally, in the late summer of 1945 the war crime on Borkum surged out of the shadows. After VE-Day, the British occupied the northern islands, including Borkum. Villagers informed the British that the seven rough-hewn wooden crosses poking out of the ground in the Borkum Presbyterian Cemetery belonged to a bomber crew that landed uninjured. Chatter from formerly imprisoned French, Polish and Russian workers building fortifications on Borkum Island during the war reached Allied ears.

A U.S. naval liaison to the British Admiral in charge of the northern sector referred the report to U.S. Military Intelligence. A preliminary inquiry in June 1945, was followed by a substantive investigation that pointed an accusatory finger at 22 Germans. Allied authorities apprehended 15 during the latter half of 1945. The remaining seven did not survive the war.

The principal assassin, Erich Langer, who fired the first bullet at Howard Graham as he struggled to make his way through the hostile crowd, died fighting the Russians. A bitter man, raging with revenge, Langer escaped earthly judgment for his crimes.

The investigation found enough evidence to recommend a trial. On October 31, 1945, Major General Lucius D. Clay, Commanding General, 7th Army and Military Governor of the Western District, signed the order creating the Borkum Island War Crimes Tribunal, known to history as U.S. versus Kurt Goebbel et al.

The tribunal, presided over by Chief Judge Colonel Edward B. Jackson with prosecution led by Major Joseph D. Bryan and the defense by Lieutenant Colonel Samuel M. Hogan (a combat veteran with no formal legal training) would decide the fate of the German defendants. Inside the splendid throne room of the Ludwigsburg Palace, the tribunal attempted to settle several legal questions while providing closure for the families of the American flyers.

With Erich Langer dead, the prosecution needed to build a conspiracy case. Could the prosecution prove that the defendants planned and carried out a conspiracy to assault and murder the flyers? If so, all 15 would hang.

Further moral and legal questions hovered over the courtroom. Could a court composed of U.S. military officers trying their former enemies for the deaths of other U.S. military officers truly operate without bias? Did Allied unrestricted bombing of civilian cities justify reprisals by the German forces on Allied aircrews? International law was ambiguous as to the justification for Allied bombing of civilian targets. Still, the law was clear on the duty of nations to protect prisoners of war.

The tribunal: judges, defense, and prosecution, got into a routine after the December 4, 1945, opening session. Through dozens of examinations and cross-examinations, the trial proceeded. The defense cast doubt on the conspiracy charges, noting that Goebell telephoned the mainland that seven prisoners would be ferried across and to be prepared for their intake. This clearly showed that the accused did not intend for the seven prisoners of war to perish that day.

As to the defendants, the main responsible parties were Goebbel, the senior military commander on the island and the man setting the brutal tone of the guard detail toward the prisoners, Erich Wentzel for failing to protect the prisoners as the senior officer accompanying the march, and Jan Akkermann, the senior government official on the island, heard repeatedly inciting the crowd of 20-30 villagers.

The remaining defendants, enlisted guards Johann Josef Schmitz, Johann Pointner, Karl Geyer, Heinz Witzke, and Jacob Wittmaack held varying degrees of culpability or inaction as witnesses to human rights violations. Pointner and Geyer mitigated their guilt as they attempted to render first aid to Howard Graham and at times were seen pushing away members of the civilian mob as they tried to slap or kick the prisoners.

Among the non-military defendants, air raid police chief Karl Weber tried to do the same, while policeman Gustav Mammenga clearly failed to arrest Langer after the first murder occurred, citing “lack of jurisdiction.”

Through January and February, U.S. vs. Goebbel became a back and forth sparring match. As the defense showed that the officers’ actions precluded a conspiracy, the prosecution punched back detailing the cover-up that followed the killings. Kurt Goebbel directed the falsification of official reports and sworn statements by the guards. In false statements to German authorities on the mainland, the accused had claimed that the prisoners died after beatings by a mob despite their efforts to protect them.

By midnight on March 23, 1946, the exhausted members of the tribunal awaited the verdict. Colonel Jackson read the names of the guilty in a clear, deliberate monotone: Kurt Goebbel (ranking officer on Borkum Island); Jacob Seiler (Goebbel’s second-in-command); Erich Wentzel (officer in charge of the column of prisoners); Johann Schmitz and Jacob Wittmaack (sergeants of the guard of the prisoners); and Jan Akkerman (Borkum mayor).

Colonel Jackson’s gavel ended the Borkum Island War Crimes Tribunal, and Schmitz, Wittmaack, and Akkermann were executed in 1948. In ensuing years, Germany went from being an enemy to defeated supplicant, then friend and ally. The political winds touched off years of appeals, resulting in reduced sentences for most of the German defendants. Kurt Goebbel had his sentence reduced on appeal, eventually receiving parole in February 1956.

On August 4, 2003, the two surviving members of 909’s aircrew, Quentin Ingerson and Kazmer Rachak, made the long journey from the United States to Borkum Island. There, in the presence of the local townspeople and surviving family members, they laid a plaque commemorating the lives of their seven fellow crewmen that did not return from that fateful flight over northern Germany on that balmy summer day long ago.

William R. Hogan is the youngest son of Colonel (Ret.) Samuel M. Hogan, and a fourth generation U.S. Army officer who has served across the world. He currently resides in Paris, serving as an exchange officer on the French Army Staff.

Thanks to Mr. Hogan for a superbly researched, clearly written and nuanced account of yet another small tragedy of WWII. This is truly one of the finest pieces of writing I have ever read here, and compares to the best books of the history of the the war. Details, details, details make the event sorrowfully come to life.

Very nice article although I seriously doubt the statement that the “undamaged machines continued on at 500 mph.” Maximum speed is generally stated to be around 300 mph.