By Joshua Shepherd

Late in the day on May 23, 1706, the troops of the Colonel William Borthwick’s regiment of Argyll’s Scots Brigade formed up for an unenviable assignment. Although repeated English attacks on the Flemish village of Ramillies had failed, Borthwick was determined to see his men break the enemy defenses.

His objective was the village church, which included a walled compound occupied by the French Picardie Regiment. While his musketeers kept up a fire on the French, Borthwick’s grenadier company would smash its way through the church gate and force an opening. Despite the straightforward plan, the grenadiers, who would clearly suffer heavy casualties, constituted a forlorn hope.

Unmoved by the consequences, 19-year-old Ensign James Gardiner gripped the Scots colors and moved forward with the grenadiers amid a blinding storm of smoke, lead, and dying men. Nearing the churchyard, the grenadiers stalled amid the heavy fire, faltered, and began to fall back. Hoping to rally them, Gardiner drove the colors into the ground and turned to shout encouragement to his men. As he did so he was struck in the mouth by a French musket ball and fell to the ground.

Two grenadiers dragged the stricken ensign to safety and propped him up against the churchyard wall. Bleeding profusely and unable to retreat, the young ensign was left alone where presumably he would die. Although the killing would continue until sunset, the sanguinary clash between a Grand Alliance army and a Franco-Bavarian army at Ramillies in the Spanish Netherlands had ended for young James Gardiner.

The inglorious bloodletting that would redden the fields of Ramillies was the direct result of an epic dynastic struggle for domination of the European mainland. By 1706 Europe was locked in its fifth year of war as the continent’s rival powers clashed over a disputed succession to the Spanish throne.

The death, and childlessness, of a single man had plunged millions into conflict. Charles II of Spain, an unfortunate soul who had been plagued for his entire life by ill health, physical deformities, and outright bad luck, died without an heir in 1700. At that time, Spain’s possessions were considerable. They encompassed the Spanish homeland on the Iberian Peninsula, southern Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Spanish Netherlands. In addition, Spain possessed a vast overseas empire that included much of South America.

The initial prospect, however, for a peaceful compromise over the throne seemed within reach. Charles had previously selected Josef Ferdinand of Bavaria, grandson of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, as his heir. The young prince was viewed as a compromise candidate for the Spanish throne. He was related to Austria’s House of Hapsburg, but acceptable to France’s ruling Bourbons. Quite unexpectedly, though, Josef Ferdinand fell ill, and, to the consternation of Europe’s monarchs, succumbed to the sickness.

Josef Ferdinand’s unfortunate death entirely destabilized the delicate diplomatic arrangement that had promised peace. King Charles of Spain, his own health quickly deteriorating, was forced to nominate a new heir, and his choice would virtually guarantee war. Charles selected Philippe of Anjou, the second grandson of King Louis XIV, France’s powerful Bourbon monarch at the time, who called himself the Sun King. Charles’ own death in autumn 1700 only served to escalate the likelihood of hostilities.

To France’s enemies, the proposed accession of a French prince to the Spanish throne threatened an unacceptable consolidation of power to the Bourbon monarchy. Fearful that France would continue to expand its influence, Austria was quick to act, invading the Spanish province of Milan. Despite last-minute diplomatic efforts, the situation rapidly deteriorated. In May 1702 England, the United Dutch Provinces, and the Holy Roman Empire issued a joint declaration of war against France. For his part, Louis XIV enjoyed alliances with Spain, Bavaria, and Cologne. The dispute over the Spanish succession had been transformed into a major war that would engulf the European Continent.

During summer 1702, Captain General John Churchill, Earl of Marlborough, arrived on the continent to take command of disparate Allied forces. Although he had never commanded a large army in the field, Marlborough was given command of the English, Dutch, and other allied forces. Churchill would wage a frustrating war of maneuver over the following two years, beset by logistical constraints and grudgingly slow support from hesitant allies. Marlborough scored a major victory in August 1704, smashing a Franco-Bavarian field army at Blenheim in northern Bavaria. Queen Anne elevated Marlborough to duke for the feat, and while widely considered one of the major tactical masterpieces of military history, the clash at Blenheim failed to materially alter the course of the war.

Marlborough hoped to break the stalemate by changing course. Rather than continue a seemingly fruitless fight in the narrow confines of the Low Countries, Marlborough made plans in 1706 for a concentration of Allied forces that would then execute a grand campaign in Italy and southern France. The plan constituted audacious and original strategic thinking, but the idea met with a cool reception from Dutch and German allies.

French advances along the Rhine River further destabilized the strategic situation in northern Europe, and the setbacks had rendered Marlborough’s plan for a grand campaign into Italy and southern France out of the question. The English duke, however, was disinclined to see the Allies assume a defensive posture. True to his aggressive nature, Marlborough opted to seize the strategic initiative by launching an alternate offensive into the Spanish Netherlands.

Certainly ahead of his time as a military thinker, Marlborough’s plan for the coming campaign broke the centuries-old European tradition of seizing and holding the enemy’s fortified strongholds. Realizing that such positions could be choked off easily if they lacked adequate logistical support, Marlborough opted to target the strategic head of the French war effort in Flanders. That target was Marshal Francois de Neufville, Duke of Villeroi’s Franco-Bavarian army. Villeroi had 60,000 troops and 70 guns.

Largely ignoring all other objectives, Marlborough single-mindedly tailored his campaign to seeking out Villeroi’s forces, forcing them into a decisive engagement, and destroying them in detail.

Marlborough led his troops out of The Hague on May 9, groping his way south and west in the hope of pinpointing Villeroi. Despite his previous frustrations in securing Allied support, the duke was at the head of an imposing force. The Allied army had 62,000 men and 120 guns.

Marlborough continued to play a delicate balancing act as both soldier and diplomat, struggling to forge a cohesive force out of a diverse collection of battalions. The army that he led into the field was a veritable European melting pot. Although largely composed of English and Dutch troops, the army included contingents of Danish, Swiss, Swedish, and Hessian auxiliaries. Despite the army’s tapestry of language and culture, the Allies were united in their repugnance for French dominance.

But in a crucial bit of unconventional generalship, Marlborough made the decision to attach a large train of Dutch siege artillery to his field army. Although the heavy guns would prove cumbersome on the march, they could furnish the duke with overwhelming firepower when used to bolster the smaller guns of the Allied field artillery. If the Allies were successful on the field, the siege train could be employed quickly against France’s network of fortified bastions along its frontier.

By May 17, Marlborough’s columns had converged at Tongeren, a Flemish town situated west of the Meuse River. Despite his swift movement and decisive posturing, the duke feared that the French would never allow themselves to be forced into a decisive battle. In a private letter, Marlborough confessed his fears. “I have no hope of doing anything considerable, unless the French do what I am very confident they will not, namely, come out and fight,” he wrote.

But Marlborough’s fears were misplaced. The war thus far had seriously depleted the French treasury and Louis XIV, hoping to hasten the end of the conflict, had ordered Villeroi to adopt an aggressive posture. Compelled to comply with the wishes of his sovereign, Villeroi began moving south and east in the presumed direction of the Allied army. To further strengthen his field army the French general stripped much of the region’s fortified strongholds of their garrison troops. Villeroi’s unexpected eagerness to give battle would afford Marlborough just the opportunity that he sought.

Quite unexpectedly, that opportunity began to materialize on the morning of May 23, 1706. The army’s quartermaster general, William Cadogan, led about 600 men westward, simply searching for a good campsite for the army for the coming evening. Marlborough had plans to take up positions on high ground just to the west of a stream known as the Petite Gheete. It was expected that the French, still thought to be maintaining a passive defense along the Dyle River, would pose no immediate threat. But as the van of Cadogan’s column inched its way forward through a dense morning fog, it abruptly encountered a patrol of enemy cavalry. Cadogan had inadvertently stumbled on the French.

The startled troopers from both sides opened up a confused exchange of gunfire, then untangled and fell back. Suspecting that the bulk of the French army could be nearby, Cadogan organized his men into a defensible line on high ground east of the valley of the Petite Gheete and sent news of his discovery to Marlborough. Waiting for the fog to break, Cadogan sat tight and awaited developments.

When Marlborough was apprised of the news, he acted quickly, dispatching mounted reinforcements to Cadogan and hurrying along the main body of his army. By midmorning, Marlborough and Cadogan met to confer, but heavy fog left the officers unsure of the enemy’s true numbers and disposition. The ever-aggressive Marlborough made plans to launch a cavalry movement straight across the valley and drive in the French pickets. But before he could do so, the fog began to lift. As it did, it revealed a truly shocking sight. Across the valley floor and situated on formidable rising ground was a massive enemy force. It was clear that Villeroi, far from shunning battle, had come out of his defenses looking for a fight.

True to his nature, Marlborough was eager to accommodate. The duke immediately issued orders for the bulk of his army to hurry forward and form up for battle along the high ground east of the Petite Gheete. As they did so, one of the Dutch observers attached to the army, Sicco van Goslinga, voiced his opposition to Marlborough’s dispositions. The Allied army was far too dispersed to give battle, warned the startled Dutchman, and was courting an outright catastrophe by not exercising greater caution. Marlborough, far from being dissuaded by the pessimistic outburst, brushed it aside and proceeded to prepare for battle.

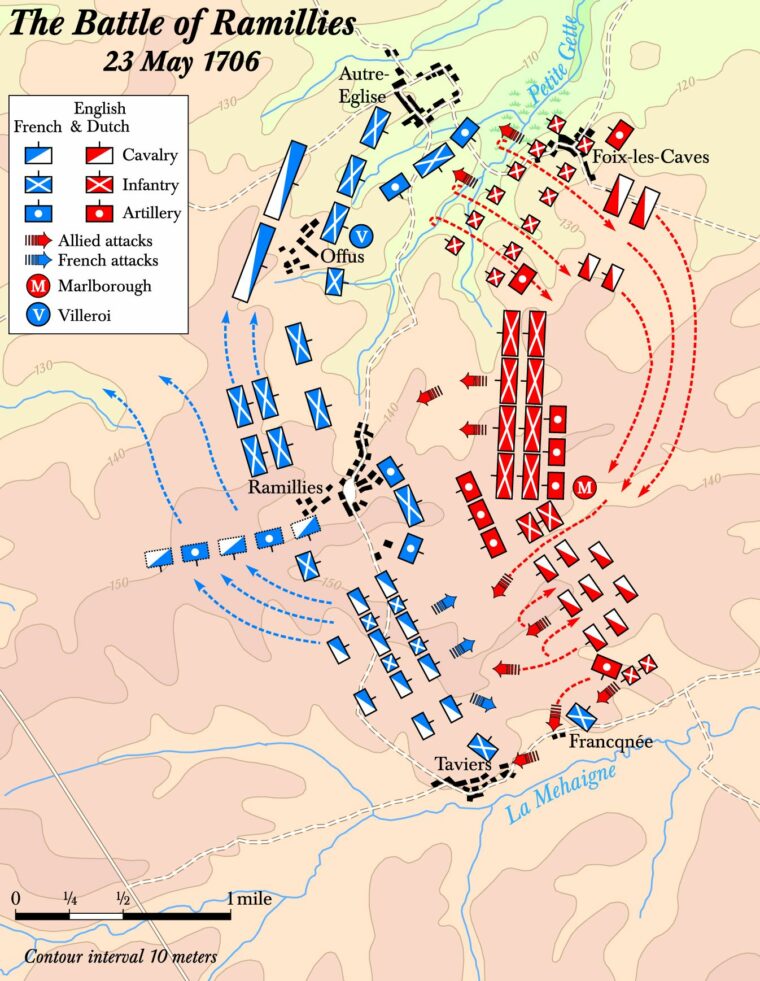

For his part, Villeroi did the same. Equally pleased that he was finally coming to grips with his nemesis, Villeroi made his final dispositions, with his center situated on the village of Ramillies. On the right, his flank was anchored on high ground bordered by the Vissoule Stream. His left, fronting the swollen Petite Gheete, was anchored around the village of Autre Eglise. It was a good position, bolstered by a string of walled farmhouses that could be transformed into strongpoints. Villeroi could also count on the services of two very capable commanders, who were lieutenant generals Pierre de Montesquiou, Comte d’Artagnan, who commanded the Bourbon center, and the Marquis Antoine de Guiscard, who commanded the right wing. Villeroi took personal command of the left wing.

As both armies readied for the inevitable, they began to open fire with their heavy guns. The dull thud of artillery fire echoed across the valley floor, the harbinger of a coming fight. The English, however, with the added firepower of the Dutch siege guns, would eventually gain the upper hand in the artillery duel.

Marlborough was keen to open the battle. He ordered Colonel Hans Felix Werdmuller to swing to the left with four battalions of the Dutch Guards and clear enemy outposts in front of the French right. Werdmuller ran into trouble almost immediately. As his men trudged toward the hamlet of Franquenee, they were met with heavy fire from dismounted enemy dragoons that had taken cover around the village. Werdmuller, whose infantry was backed up with a pair of light guns, deployed in line of battle and pushed toward the farmhouse. His force quickly overwhelmed its defenders with heavy volleys of musketry. Outnumbered and outmatched, the dragoons fled for the rear.

As they did so, they sought protection in the hamlet of Taviers, a key outpost that secured Villeroi’s right flank. Although the French general had planned for three battalions to defend the village, the locale was only occupied by a single company of Swiss troops when Werdmuller’s column approached. After a brief but sharp fight, Werdmuller’s men forced their way through the village, pushing out the Swiss defenders and driving for the confluence of the Vissoule Stream and the Mehaigne River.

Apprehending the threat to their right, French commanders on the ground acted quickly to secure the flank and halt Werdmuller’s advance. The Marquis de Guiscard, the lieutenant general in overall command of the French right, sent forward five dragoon regiments from his rear line in an effort to quickly blunt the Allied thrust. As they neared the swollen waters of the Vissoule, the dragoons encountered muddy bottom ground and dismounted before pressing forward.

As they struggled through the mud, they were taken under heavy fire from Werdmuller’s infantry. Exultant after their successful fight that morning and afforded ample time to receive a counterattack, they fired a powerful volley that caught the enemy dragoons in the open. The musketry stalled their advance and inflicted heavy casualties. Officers suffered disproportionately. The Siegneur d’Aubigne, gamely leading his men forward, was cut down by Dutch musketry.

Guiscard fully realized the threat that Werdmuller’s attack posed to the French right, and so he ordered two full infantry brigades to move out in support of the dragoons. Although the Bourbon forces enjoyed a healthy numerical advantage over Werdmuller, their troops were unfortunately arriving in action in a piecemeal fashion, affording Werdmuller the opportunity to fend off the counterattacks individually.

Two French battalions, Provence and Bassigny, happened to stumble astride Werdmuller’s right flank. They poured enfilading fire into the Dutch line. The Dutch commander, however, remained unflappable. Turning his right flank to meet the threat and unleashing a heavy fire of his own, Werdmuller succeeded in holding on to his position. The uncoordinated French counterattacks ensured that the hapless Bourbon infantry was destroyed in a vain attempt to dislodge the Dutch.

Despite a decided edge in manpower, the piecemeal Bourbon attack degenerated into a fiasco. One regiment after another became bogged down in the muddy ground as it struggled to fight its way forward toward the Dutch. Lt. Col. Jean de la Colonie attempted to get his troops in position to attack the Dutch, but panic in the face of heavy musketry had become contagious. Colonie recalled the perilous approach, explaining that his men had struggled through the knee-deep water. “The dragoons and the Swiss who had preceded us [had come] tumbling down upon my troops in full flight,” he wrote, “and a number of my men turned and fled with them.”

Villeroi faced a major setback on his right. Colonie and a handful of fellow officers succeeded in rallying about four ragged battalions of infantry to offer the Bourbon right a semblance of defense, but the morning’s clash had been nothing short of calamitous. Superior numbers had been wasted in a vain and clumsy attempt to push back Werdmuller, and the French right had been nearly wrecked.

In front of the French left, Marlborough would soon launch another attack. At 2:30 p.m. Lt. Gen. George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney, led forward a strong contingent of Marlborough’s infantry. Consisting of 5,000 men, the troops were experienced, possessed good morale, and were led by capable officers. Angling for the villages of Offus and Autre-Eglise, Orkney aimed at nothing less than the destruction of the French left.

His troops struggled mightily as they advanced through deep mud to come to grips with the enemy line. It was the same kind of ordeal that had undone their French counterparts on the opposite flank. Harassed by French pickets and bombarded by enemy artillery, Orkney’s men suffered galling casualties as they fought to close the distance to the enemy. The Petite Gheete, intersected by numerous small tributaries, slowed the advance. Well-aimed artillery tore apart assault formations. Dead and wounded men blanketed the hillsides and bloodied the creeks.

Yet Orkney’s hardened troops pressed forward despite the terrain obstacles. Orkney himself, wildly waving his sword, personally led his men forward on foot. Leaving his left-most battalions near the Petite Gheete to tie down the French line, he ordered his right to angle toward Autre-Eglise.

The German and Walloon infantry that held the town let loose devastating volleys of musketry. Under such heavy fire, the redcoats pressed forward, and were soon threatening the Bourbon left. Lt. Gen. Count Christian von Birkenfeld, sensing the danger to Villeroi’s flank, ordered a counterattack by the French Regiment du Roi. Tearing into the Allied column, the French halted the advance. A brutal melee then ensued. Wielding bayonets and clubbed muskets, the Frenchmen succeeded in driving off the redcoats.

Far from undone, Orkney ordered a renewed push and watched as his men streamed forward. Orkney was a seasoned veteran, but even he found the musketry and artillery fire to be the heaviest he had ever seen. “Indeed, I think I never had more shot about my ears,” he wrote. But by his reckoning, his troops, still intact after the initial fighting, were ready to overwhelm the enemy in Autre-Eglise. However, before the final attack could be launched, fresh orders arrived from Marlborough instructing Orkney to disengage.

The irascible earl was dumbfounded. Certain that the duke misunderstood the tactical situation in front of Autre-Eglise, Orkney refused to follow the order, and a string of frustrated aides received the same response, which was that the Scottish earl refused to budge. Exasperated by the stubborn response, Marlborough dispatched Cadogan with direct orders for Orkney to fall back. Only after a contentious argument did Orkney relent. In something of an understatement, he later explained that “it vexed me to retire.” Marlborough, however, seems to have had no intention of forcing the Bourbon left, but rather deceiving the enemy as to his true intentions. While Orkney and his stalwart redcoats had battled it out on that flank, Marlborough put in motion an audacious plan to smash the opposite end of Villeroi’s line. While the French general distributed his battalions widely to meet the attacks on his left, Marlborough concentrated his forces against the Franco-Bavarian army’s weakened center and right.

Having set the trap, Marlborough made the decision to unleash a grand charge against the French right that had already been pushed back by Werdmuller’s earlier attack. The attack would be commanded by Field Marshall Hendrik van Nassau-Ouwerkerk. Ouwerkerk was the ideal commander for such an attempt. An experienced officer and thoroughgoing enemy of French and Spanish interlopers, the fiery Dutch nobleman was in his element for the most important battle of his life.

Ouwerkerk commanded an impressive force, roughly half of the army’s mounted arm, consisting of 69 squadrons of horsemen. Arrayed in three dense lines, they were composed of a diverse lot of Allied troopers, including Dutch, Danes, and Germans. To bolster the attack, Marlborough sent additional reinforcements to support Ouwerkerk. Lt. Gen. Matthias Hoeufft, leading 21 squadrons of cavalry and dragoons, was ordered to take up positions behind Ouwerkerk. So long as the French were denied the ability to reinforce their own cavalry, the Allies would enjoy a decided advantage in numbers.

Ouwerkerk’s leading columns advanced slowly, saving their energy for the final clash. Passing south of the village of Ramillies, the Allied horsemen quickly caught sight of the enemy. French cavalry in crisp ranks awaited them. At the front of the French cavalry was the Maison du Roi, the French king’s elite guard horsemen. They were determined to maintain the field and uphold the honor of their king.

Hoping to break up the Allied attack before it could gather momentum, Guiscard ordered the guardsmen forward. As the French came forward at the gallop, the commander of the Allied first line, Lt. Gen. Count Friedrich Cirksena of Oostfriesland, ordered his troopers to close ranks in order to present a solid wall of horse to the enemy. In the final moments, both sides spurred their horses to a gallop.

They met in a thunderous crash that survivors never forgot. In a swirling maelstrom of tumbling horses, flashing steel and stricken men, Europe’s mounted warriors struggled in one of the largest cavalry clashes of the century. In short order, the French gained the upper hand, driving deep into Cirksena’s lines and plunging into the rear ranks of Allied horsemen.

The fighting shifted east as Ouwerkerk’s troopers, overwhelmed by French pressure, gave ground and fled to the south of Ramillies. Exultant French horsemen pressed their advantage, but were met with renewed resistance as Allied officers rallied their men and turned on their pursuers. As both sides funneled more men and horses into the battle, the fight degenerated into a brutal brawl in which neither side could gain the upper hand.

Marlborough sent orders for more Allied cavalry to reinforce Ouwerkerk, and then personally trotted into the scene to bring order to his demoralized horsemen. Amid the confusion of retreating men, the duke became separated from his escort. As French cavalrymen closed in, he turned his horse to the safety of Allied lines, but was thrown to the ground by his mount. Seeing that Marlborough was about to be captured or perhaps even killed, Maj. Gen. Robert Murray ordered a group of his Protestant Swiss troops forward to rescue him. The troops saved Marlborough just in the nick of time before the French horsemen reached him.

To the north of the cavalry fight, Marlborough issued orders that would deliver a fatal blow to the Bourbon army on the battlefield. In front of Ramillies village, a strong contingent of the Allied infantry had formed up in three deep lines in preparation for a massive assault on the enemy’s center. The lead troops, commanded by Colonel Karl Wilhelm von Sparre, were sure to suffer terrible casualties as they spearheaded the attack.

As they moved forward in crisp formations, the Allied infantry was subjected to heavy artillery fire but pressed on. Fortunately, the rolling terrain offered a modicum of protection when intervening rises in the ground temporarily obscured the troops from French gunners. But as they neared the town, they were greeted with heavy small arms fire. A determined body of Bourbon infantry defended Ramillies where they fired from the protection of homes, wood fences, and stone walls. Bavarian infantry held the right of the line, while the French Picardie Regiment defended the left of the line.

As the attack of the front rank stalled under a galling fire, the commander of the rear lines, Willem van Soutlande, ordered reserve troops to spread out and cover the flanks: the Dutch Scots Brigade to the north and the Dutch Guards to the south. With the Allied lines extended far beyond their own flanks, the Bourbon defenders of Ramillies grew increasingly demoralized. The Dutch Guards, after they succeeded in making their way to the front of the Bavarian position, dressed ranks and made a mad charge toward the enemy. Rattled by the ferocity of the attack, the Bavarian troops broke and ran for the rear.

The outer defenses of Ramillies had begun to crack but were far from broken. With Sparre’s troops stalled east of the village, help was on the way from the northeast. Marching fast toward the battle was the Scots Brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. John Campbell, Duke of Argyll. Aiming for the church steeple in the city center, the fiery Argyll, waving a sword above his head and shouting orders to his men, personally led the attack through the town.

As they approached their target, French soldiers poured fire into the front ranks of the Scots as they approached the walled courtyard of the church. While his line companies returned fire on the French defenders, Colonel William Borthwick ordered his grenadiers to batter down the churchyard gate. The Scottish grenadiers reeled under the French fire. It was at this time that Ensign Gardiner was wounded by enemy fire.

quarter was given.

As the Scots regrouped, they were suddenly attacked at close quarters by a battalion of Irish troops under the command of Colonel Charles O’Brien, Viscount of Clare. What developed was a vicious blood feud, carried out with little quarter asked or given. The two opponents both wore nearly identical red coats, which contributed to the confusion of the fighting. Borthwick was killed outright during the struggle, and Clare was mortally wounded. The Scots’ attempt to seize Ramillies had stalled.

On the left, the fortunes of battle would soon turn in Marlborough’s favor. Ouwerkerk, who had been holding his own against the French cavalry, was reinforced with a contingent of 4,000 Danish horsemen. As the Danish horse plunged into the fight, their added numbers unexpectedly turned the tide of battle. Overwhelmed at last, exhausted and demoralized French horsemen began falling back. Guiscard was obliged to order a retreat.

Riding west and then north, the Bourbon cavalry attempted to reorganize in the rear of Villeroi’s battle line, but lost men due to straggling in the process. Ouwerkerk gave chase, then stopped on high ground west of Ramillies to regroup his victorious squadrons.

Realizing that the center of the Bourbon line would soon face renewed pressure, d’Artagnan positioned five battalions in a south-facing line as a modicum of protection from the Allied cavalry. It was little more than a desperate measure to buy time. Sparre and Soutelande again got their infantry battalions moving, attacking the beleaguered defenders of Ramillies. Once again, the Bourbon troops gave a good accounting of themselves, but the mounting pressure from Marlborough’s infantry ultimately rendered the Bourbon position untenable.

Brigadier General Alessandro Scipione, Marquis de Maffei, commanding the Bavarians manning the southern defenses of the town, ordered a retreat. D’Artagnan personally took command of the northern defenses of the village, rushing forward dwindling reserves in a desperate attempt to hold onto Ramillies.

For Villeroi, matters only worsened. Having entirely outgeneraled his French counterpart, Marlborough was able to continue throwing overwhelming numbers of fresh troops into the crucial sector of the battlefield. Marlborough ordered two additional brigades, commanded by brigadiers George Macartney and Phillip von Donop, to cross the Petite Gheete north of Ramillies. Their attack, which threatened to cut off the defenders of Ramillies, elicited a desperate response from d’Artagnan.

The Frenchman pleaded for immediate assistance from the Marquis de Montpesat, who commanded nine battalions of French and Swiss Guards. The elite troops had been held in reserve for emergency, and launched a ferocious counterattack, smashing Macartney and Donop’s brigades and sweeping across the Petite Gheete. The impetuous and costly attack succeeded brilliantly, but afforded the Bourbon army only a temporary reprieve from the inevitable.

Realizing that his position had become untenable, Villeroi ordered a withdrawal and a redeployment centered on the village of Offus. He hoped that the Bourbon army would be able to hold off the Allies long enough at that location to disengage once again and withdraw toward Louvain. Troops trapped in Ramillies were ordered to abandon their baggage and artillery and break out as best they could.

Marlborough, though, gave his opponent little respite. With the momentum of the battle clearly turned in his favor, the duke sought to deliver the coup de grace to the Bourbon army. Ordering Ouwerkerk’s reinforced and regrouped cavalry squadrons to launch a fresh attack, Marlborough turned loose nearly 18,000 horsemen in a broad sweep across the enemy’s rear. Effective Bourbon resistance crumbled in front of the impressive charge, and Ouwerkerk’s horsemen wrought havoc among stragglers, baggage trains, and disrupted enemy units.

On the Allied right, Orkney witnessed Bourbon forces falling back from Autre-Eglise and decided to pounce, sending forward his infantry in a belated push for the town. On the far right, Lt. Col. Lord John Hay led Scottish and Irish cavalry in a thundering charge that caught the French Regiment du Roi entirely by surprise. The French guards were hastily gathering their baggage and unprepared for the attack. Hay’s horsemen tore up two battalions of the regiment, capturing a large lot of prisoners, before the rest of the French guards were able to form up and drive off their attackers with several well-directed volleys.

Despite the near-collapse of the Bourbon army, Villeroi still had infantry units capable of putting up a fight. Without infantry support, English cavalry ranging around the enemy left was incapable of doing much execution against stubborn ranks of Bourbon foot soldiers. Villeroi’s army had been badly shattered, but its complete destruction remained unattainable. The aggressive Orkney, disappointed to see the enemy escaping, vented his frustrations. “It vexed me to see a great body of them going off,” he wrote.

Dazed by the reverse he had suffered at the hands of Marlborough, Villeroi ordered a general retreat. He issued orders to his subordinates directing them to extract their troops as best they could and regroup at Tirlemont on the Dyle River. Allied horse and foot harassed the retreating Bourbon troops until darkness put an end to the fighting. Villeroi narrowly succeeded in pulling the core of his army out of the noose, but it had been wrecked as a functioning field force.

The charred battlefield itself would reveal an Allied victory of staggering proportions. Marlborough’s exultant troops had captured scores of enemy cannon and 80 enemy flags. Whereas the Franco-Bavarian army lost 13,000 men, Marlborough’s Grand Alliance army had suffered just 4,000 casualties. Among the survivors of the clash of arms was Ensign James Gardiner. The ball which struck him had miraculously passed through his mouth and neck without striking teeth, bone, or artery. Though in great pain, he was rescued the following morning.

Despite the tragic loss of life, the fallout of the battle proved even more disastrous for King Louis’ war effort. In the wake of the fight at Ramillies, Marlborough continued to pursue and harrass Villeroi’s defeated army, pushing it toward the frontiers of France. The duke then proceeded to snatch up the weakened garrisons of towns and fortresses across the Spanish Netherlands. Louvain fell to the Grand Alliance on May 25, Brussels on May 27, and Antwerp on June 5. By the close of the campaign season, French forces had largely been driven west of the Meuse River.

In a broad arc across Europe, Bourbon forces were placed on their heels due to the staggering defeat at Ramillies. In an effort to rebuild defenses in Flanders, Louis XIV transferred French and Spanish troops from Spain and Italy, ensuring that the strategic initiative would rest with Allied forces. For her part, the English monarch Queen Anne was ecstatic over the potential fruits of Marlborough’s victory. “Now we have, God be thanked, so hopeful a prospect of peace,” she wrote.

The Treaty of Utrecht signed in 1713 allowed King Philip V of Spain to keep the Spanish throne in return for permanently renouncing his claim to the French throne. For his part, Louis XIV agreed that the crowns of France and Spain should not merge. The war dragged on, however, between the Holy Roman Empire and France until Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI signed the Treaty of Baden the following year.

France would persist as a major world power, but the War of the Spanish Succession was a harbinger of the French monarchy’s waning influence. The ultimate lesson of the long war for the great powers was that maintaining a careful balance of power was more important than dynastic rights.

Louis XIV, who had made war a way of life for the French people, realized that the French power had been curtailed in the wake of many defeats at the hands of the Grand Alliance. Attempting to console Villeroi for the shifting fortunes of the battlefield, the French king told him, “At our age, marshal, we must no longer expect good fortune.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments