By Blaine Taylor

In May 1867, French ruler Napoleon III hosted a gala Great Universal Exposition that proved to be the high-water mark of his ornate but tissue-thin Second Empire. Among the glittering guests that day was Wilhelm I, King of Prussia. The two ruling sovereigns addressed each other as “my dear brother,” but their civility and good cheer masked the fact that Napoleonic France and upstart Prussia were on an unavoidable collision course to war. In the distance, storm clouds were gathering.

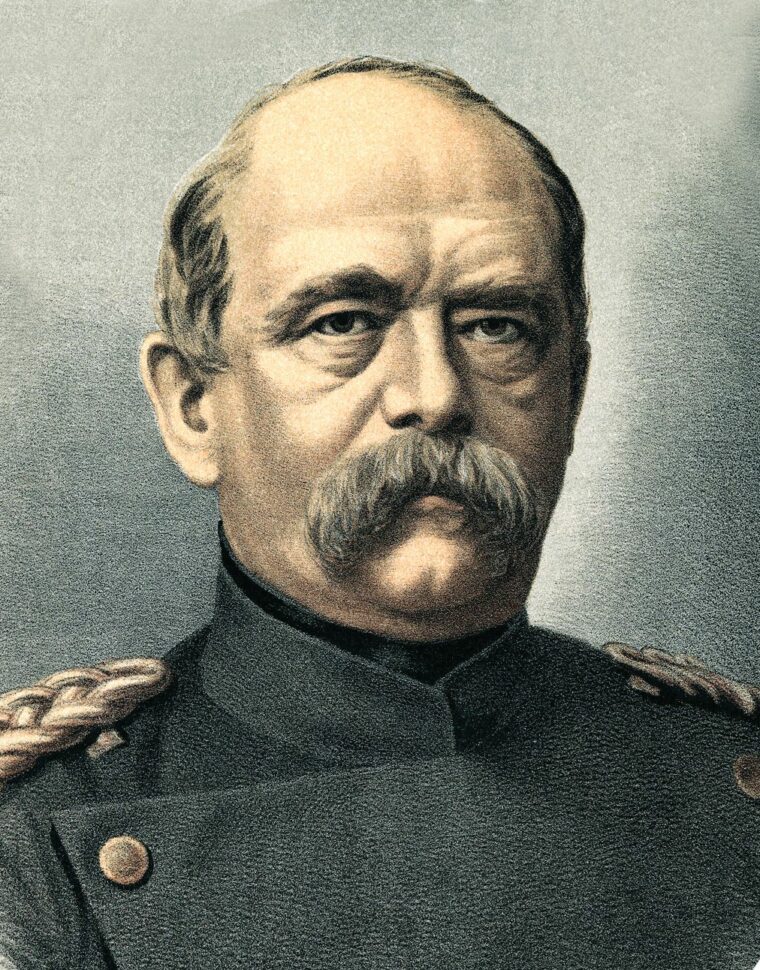

The man who would help launch that storm was Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck, the head of Wilhelm’s government at Berlin. Bismarck had already masterminded the formation of the smaller Teutonic states into the North German Confederation in 1866, with Prussia as its linchpin. Moreover, as Prussia’s “blood and iron chancellor” since 1862, Bismarck was completely unimpressed with Napoleon III, characterizing him dismissively as “a sphinx without a riddle.”

While Bismarck recognized that France was Prussia’s most formidable continental foe, he also believed that when the time came he could circumvent the unwary French ruler. He was more concerned about completing German unification without the intervention of the other major European powers that had a vested interest in preventing such a unification—Romanov Russia, Habsburg Austria, and Victorian England.

Czarist Russia, angered by the Franco-British coalition that had defeated her in the Crimean War of 1854-1856, stood aside during Prussia’s Unification Wars, thus giving Bismarck a free hand to do his work. Allied with Austria in 1864, Prussia had prevented Denmark from annexing the pro-German duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, then defeated Austria two years later to establish unquestioned Prussian hegemony within Germany and seized both duchies for herself.

In Paris, Napoleon III had also remained neutral, believing that Prussia could not vanquish Austria alone. He did not want to see France tied down in another Seven Years’ War. Like many other military observers, Napoleon III was frankly amazed at the speedy demise of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the Six Weeks’ War. The last thing he wanted was a war with suddenly mighty Prussia.

Time had not been kind to Napoleon III’s tottering regime. In March 1867, the French had pressured King William III of Holland to cede Luxembourg to France, but Bismarck refused to countenance such a territorial acquisition and successfully blocked the move. Three months later, on June 19, the Austrian claimant to the Mexican throne, Emperor Maximilian, was captured and shot by a Juarista firing squad after the French bayonets that had propped up his regime had been withdrawn in the face of diplomatic demands from the angered United States. On top of everything else, the “Little Napoleon” was already a very sick man, afflicted with painful gallstones.

Meanwhile, a new diplomatic disaster for Napoleon III was brewing closer to home as the new decade began. It involved the so-called “Hohenzollern candidature” for the vacant throne of Spain. Two years earlier, in 1868, the unruly Spaniards had ejected corrupt and sexually promiscuous Queen Isabella II from her throne. In 1870, the crown was offered to young Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, the Catholic branch of the mainly Protestant Prussian ruling House of Hohenzollern.

Neither Leopold nor King Wilhelm, as head of the family, favored accepting the Spanish offer. The ever-scheming Bismarck was for it, though, because he realized that the prospect of Hohenzollern kings reigning on both France’s Rhenish and Spanish frontiers was a political and military threat that no French ruler could countenance. Meanwhile, Napoleon III’s wife, the Spanish-born Empress Eugenie, was already thinking seriously about a regency in which she ruled France alone to ensure that the throne would remain secure for their son and heir, the Prince Imperial. Worried that her husband would never agree to step down, she moaned, “We are marching to our downfall, and the best thing would be if the Emperor would disappear suddenly, at least for the time being.”

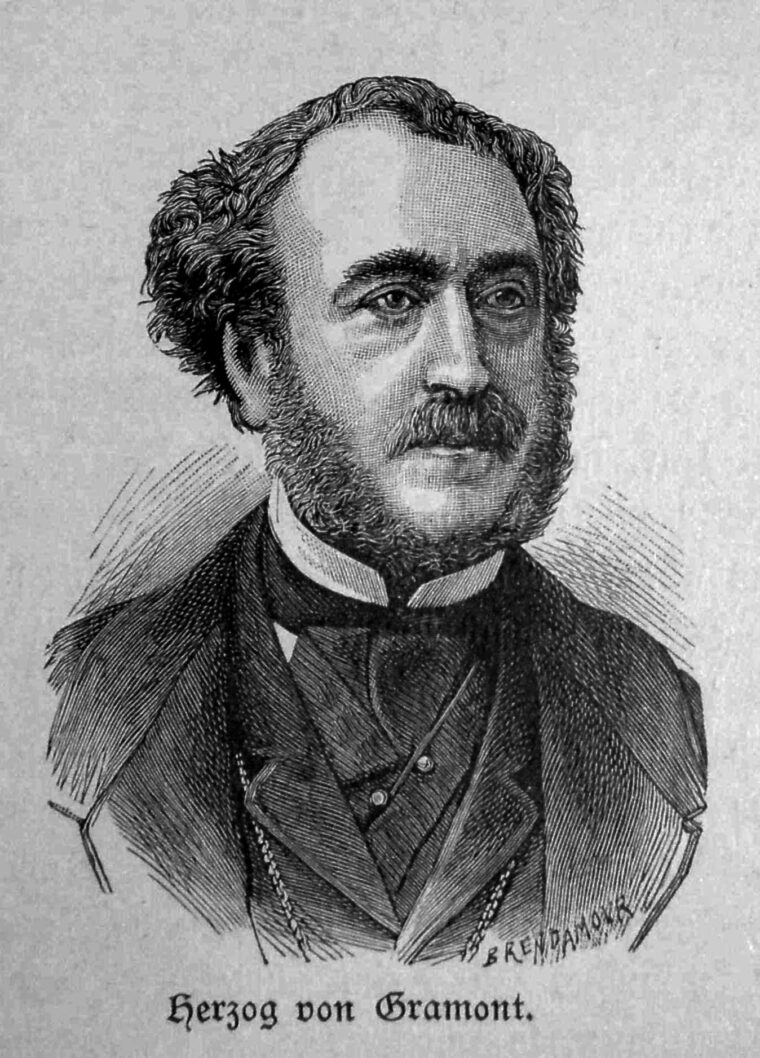

Ultimately, Leopold renounced the Hohenzollern candidacy, but Napoleon III’s new foreign minister, the Duc de Gramont, wanted more. He thundered that the now-refused offer had threatened the balance of power in Europe and “placed in peril the interests and the honor of France.” He said the nation relied “on the wisdom of the German and the friendship of the Spanish people. But if it proves otherwise, then we would know how to fulfill our duty without hesitation and without weakness.” Bismarck, reading the speech, commented with some satisfaction, “This certainly looks like war.”

Compounding his error, Gramont directed the French ambassador to Berlin, Count Vincent Benedetti, to extract a further promise from King Wilhelm I that neither Leopold nor any other German prince would ever consider sitting on the Spanish throne. If Wilhelm refused, said Gramont, “It will be war at once, and in a few days, we will be on the Rhine.” He urged Benedetti to act swiftly, before the Prussians had the chance to mobilize their own troops. “You cannot imagine how excited public opinion is,” wrote Gramont. “It is overtaking us on every side and we are counting the hours.”

In the midst of the diplomatic furor, Wilhelm happened to be taking a health cure at the German resort town of Ems, east of Koblentz on the Lahn River in Hesse-Nassau. On the morning of July 13, 1870, he was strolling unconcernedly in the park with his aides when the French ambassador violated protocol and approached him directly. Remarkably, a photograph exists of the encounter, showing a top hat-wearing Wilhelm and a straw hat-wearing Benedetti walking side by side. Each is using a cane.

By all accounts, the brief conversation was cordial, if carefully cool. Wilhelm congratulated the Frenchman on the news of Leopold’s refusal of the Spanish offer. Benedetti, as instructed by Gramont, demanded that the king give assurances that such a thing would never happen again. Wilhelm politely refused, saying he could not bind himself or the nation to such an ironclad position for the unforeseeable future. The two men parted within minutes. A little later in the day, Wilhelm forwarded Benedetti a copy of the formal letter of renunciation that Prince Leopold’s father, Charles Antony, had sent to the Spanish ministry. The letter, Wilhelm noted, had “his entire and unreserved approval.” When Benedetti asked for another meeting to press his demands for a formal guarantee, Wilhelm replied that as far as he was concerned there was nothing further to discuss.

Afterward, Royal Secretary Heinrich Abeken sent the following telegram to Bismarck: “His Majesty the King has written to me: ‘Count Benedetti intercepted me on the promenade and ended by demanding of me in a very importunate manner that I should authorize him to telegraph at once that I bound myself in perpetuity never again to give my consent if the Hohenzollerns renewed their candidature. I rejected this demand somewhat sternly, as it is neither right nor possible to undertake engagements of this kind forever and ever. Naturally, I told him that I had not yet received any news, and since he had been better informed via Paris and Madrid than I was, he must surely see that my government was not concerned in the matter.’ The king decided in view of the above-mentioned demands, not to receive Count Benedetti anymore, but to have him informed, by an adjutant, that His Majesty had now received confirmation of the news which Benedetti had already had from Paris and had nothing further to say to the ambassador. His Majesty suggests to Your Excellency that Benedetti’s new demand and its rejection might well be communicated both to our ambassadors and to the Press.”

Bismarck was the ultimate opportunist, waiting for just the right moment to strike. “One must wait for the Goddess of History to pass, then grasp the hem of her garment as she does, being carried along with it,” he had noted in the past. After receiving Abeken’s telegram, Bismarck edited it slightly to sharpen the apparent differences between the offended king and the importunate French diplomat. The new Ems Telegram, which Bismarck forwarded to all Prussian ministries abroad, was subtly but tellingly different in tone: “After the news of the renunciation of the Prince of Hohenzollern had been communicated to the Imperial French government by the Royal Spanish government, the French Ambassador in Ems made a further demand of His Majesty the King that he should authorize him to telegraph to Paris that His Majesty the King undertook for all time never again to give his assent should the Hohenzollerns once more take up their candidature. His Majesty the King thereupon refused to receive the ambassador again, and had the latter informed by the adjutant of the day that His Majesty had no further communication to make to the ambassador.”

Bismarck was privately exultant. “This will be a red rag to the Gallic bull!” he chortled to confidants as the second version of the events in the garden at Ems was released for publication to all diplomatic posts and news bureaus in Berlin. A third version appeared, inadvertently strengthening Bismarck’s hand, when the French translation by the Havas Agency altered the ambassador’s demand into a question and also translated the German term for adjutant (a high-ranking aide de camp) into the French term for a low-ranking noncommissioned officer. It was this third version that was published the next day in French newspapers. Ironically, it was Bastille Day.

Now both sides believed themselves simultaneously insulted: the Germans in having the much-revered Prussian monarch humiliated, and the French in having that king brush off their duly appointed representative before he could deliver his message in full detail. Angry citizens filled the Paris and Berlin streets demanding satisfaction and crowing intemperately about national honor.

On the German side, only Bismarck and select Prussian Army leaders wanted war, while the king, the queen, the crown prince, and the crown princess all opposed it. On the French side, virtually everyone—both military and public, and foremost the Empress—was for the war, while the sick emperor eventually was persuaded as well. Of the French marshals and generals, Eugenie later recalled, “They all vouched for our victory: ‘We shall swallow Prussia at one gulp!’” Only left-wing assemblyman Louis Adolphe Thiers rose to speak out against the looming war. “Do you want all Europe to say that although the substance of the quarrel was settled, you have decided to pour out torrents of blood over a mere matter of form?” That was precisely what French leaders had decided.

Without having the support of a single European ally, France declared war on Prussia five days later, on July 19, 1870. The overconfident French Army always intended to invade Germany first, but France suddenly found herself invaded instead. After losing several engagements, the main French army was surrounded and defeated at the Battle of Sedan on September 1, with Napoleon III surrendering as well. On the 4th, the Third French Republic was proclaimed in Paris, and Eugenie sought asylum in neutral Britain. The Second Empire had fallen ignominiously and completely, as she had once more clearheadedly predicted.

In January 1871, besieged Paris also fell. The Prussian Army staged a victory parade, and King Wilhelm was proclaimed German emperor by his fellow Teutonic princes. Bismarck, whose editing skills had equaled his back room machinations, was named a count and promoted to the rank of full general.

The last French Bonapartes all died in exile: the deposed emperor died in England in 1873, the Prince Imperial was killed in the Zulu War of 1879, and ex-Empress Eugenie expired in 1922, but not before seeing the hated German Empire fall in 1918. The following year, an angry Berlin mob publicly burned the captured French battle flags and standards of 1870. It seemed, in retrospect at least, that no one had wanted the war that one artfully edited telegram had so carefully and callously instigated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments