By Jon Diamond

Why was Myitkyina such an important objective in the reconquest of Burma in 1943 through 1944 for the Allies and especially among them, Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell? After the inglorious Allied retreat through Burma in early 1942, with the ensuing capture of that entire country by Japanese forces, China was to become wholly isolated from resupply save for the dangerous air route over the Himalayas called The Hump. At a press conference, Stilwell made the now famous statement: “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back, and retake it.”

Coincidental with the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from France in June 1940 was the “voluntary closure” of the Burma Road by the British under Japanese coercion. This occurred after the Vichy government allowed the Japanese to occupy northern Indochina, effectively isolating China completely. The Burma Road ran from Lashio, south of Myitkyina, through the mountains to Kunming in China and up to Chunking. The road was constructed through the efforts of several hundred thousand Chinese laborers and wound through high mountain ranges and their low-lying valleys as well as across two rivers, the Mekong and Salween.

Although primitive from a civil engineering standpoint, the Burma Road was nonetheless one of Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek’s last conduits for resupply since he had already lost the coast of eastern China to the Japanese. Thus, the British closure of the Burma Road severely impeded the flow of supplies to Chiang’s new capital.

The loss of Rangoon within two to three months of the start of hostilities and then the remainder of Burma severely impeded Allied operations in Asia. China was usually supplied first by ship at Rangoon, then by rail to Lashio, and finally by truck convoy over the Burma Road to Kunming. With Rangoon now under Japanese control, this supply chain was broken. Without military assistance, China would be forced to surrender, and Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) forces could be diverted to other Pacific war zones.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) at their Trident and Quadrant Conferences in Washington and Quebec, respectively, established a need for a land operation to capture northern Burma to improve the air route and establish overland communications with China with a target date of mid-February 1944. Another goal was to continue to build up and increase the air routes and air supplies to China and to develop air facilities with a view to keeping China in the war. Stated succinctly, all parties in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater were clamoring for more supplies and war matériel. However, it was apparent in 1942-1943 that an airlift alone would be inadequate for an enlarging force to go on the offensive in China, let alone to keep Chiang’s government supplied to the minimum degree necessary to remain in conflict with Japan.

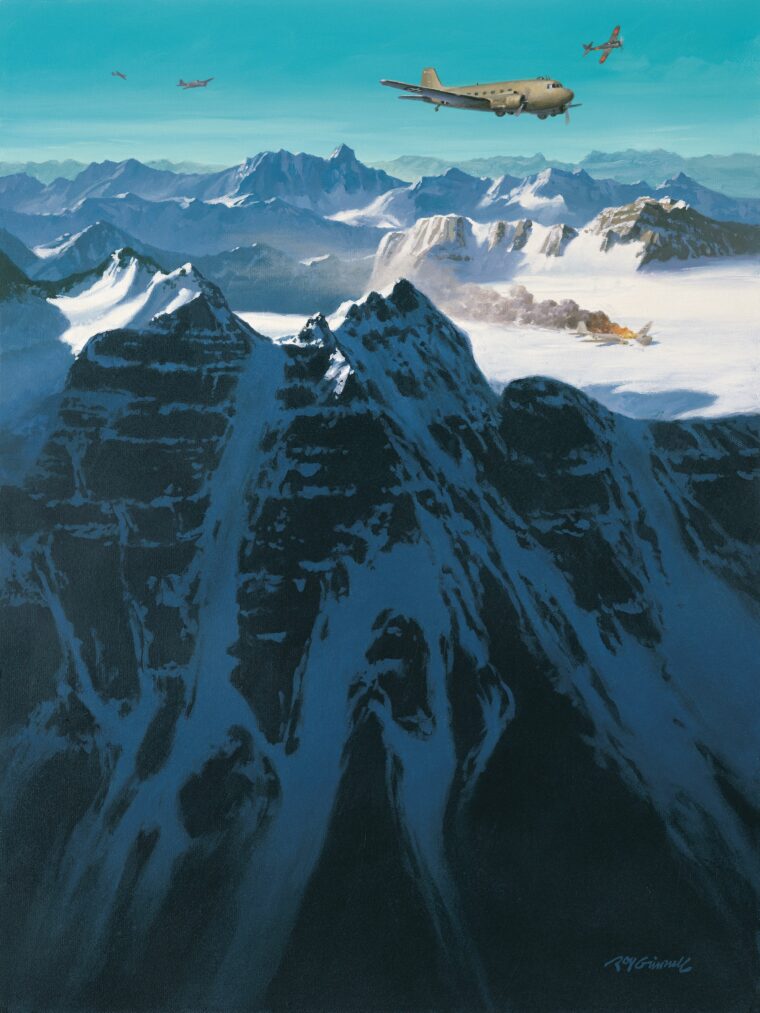

To accomplish the aims of the CCS, the capture of Myitkyina in north Burma became of paramount importance. Myitkyina, at the junction of the Mogaung and Hukawng Valleys, lies at the southern tip of the Hump, which U.S. cargo planes of the Air Transport Command (ATC) had to fly over in their trek from air depots in India to their terminals at Yunnanyi and Kunming in southwestern China.

Due to the threat of Japanese fighters stationed at the Myitkyina airfield, these transport aircraft had to fly far to the north of the more direct line from Chabua, India, to Yunnanyi and Kunming, and then swing south to the Chinese air terminals. However, this safer detour increased fuel consumption and reduced the load among the transports.

Furthermore, the air route itself was narrow, and its saturation with transports sometime in the near future was predicted. This supply nightmare would persist as long as Myitkyina remained in Japanese hands as the base for elements of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force’s (IJAAF) 5th Air Division. With Myitkyina in Allied possession, the transport crews would be able to resume the more southerly air route and avoid the geographical hazards of the Himalayan peaks in addition to reaping the logistical benefits.

According to Stilwell biographer Barbara Tuchman, “The ATC burned one gallon of fuel for every gallon it delivered to China and had to deliver 18 tons of supplies to enable [General Claire] Chennault’s air force to drop one ton of bombs on the Japanese. A single cargo plane could carry approximately four to five tons and under optimum conditions could make one round trip per day. But rarely more that 60-70 percent of assigned planes was in operation at any one time, and weather and other failures reduced the flight. Losses over the route were heavy. In three years of operation the ATC was to lose 468 planes, an average of 13 a month. Sometimes the crew was able to parachute to safety and be guided out by Kachin rescue teams organized by OSS agents in Burma. Others died in the jungle or were captured by the Japanese or in some cases were caught in the tree tops and their corpses found hanging long afterwards, eaten by ants.“

Another important reason for Stilwell and his Sino-American forces to capture Myitkyina centered on the fact that since the autumn of 1942 U.S. Army engineers had been building a road south from Ledo in Assam, India, which was intended to cross northern Burma and ultimately link with the old Burma Road at Mong Yu, which lies between Bhamo and Lashio. The Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys, through which this Ledo Road was to be constructed, entered the Irrawaddy Valley within a few miles of Myitkyina.

The city of Myitkyina was key to the rail and road net of prewar Burma, so when the Ledo Road reached it, the engineering problem would become one of improving existing facilities rather than constructing new ones. Therefore, taking Myitkyina was the prerequisite for completing the Ledo Road’s juncture with the Burma Road, establishing a point where land communication could be reopened with China via an all-weather road with a gasoline pipeline.

According to official historians of the CBI, “One of the noteworthy aspects of the North Burma Campaign of 1943-1944 is that the logistical preparations, the planning, and the fighting proceeded simultaneously.”

Stilwell started his military advance with the Ledo Road’s construction following him and using his Chinese 38th Division as outpost protection for the American road engineers before getting official orders from the CCS. As the overseer for all Lend-Lease aid to China, Stilwell knew that aerial resupply would be insufficient, especially if the northern arc for the ATC planes was maintained to avoid Japanese fighters.

Upon receiving the directive from the CCS to advance into northern Burma, Stilwell also gained the approval from the Chinese to augment his offensive in the late autumn of 1943 with the Chinese 22nd Division which had been training in Ramgarh, India. This time point was to correspond with a little known IJAAF air assault from October 13-27, 1943, Operation Tsuzigiri, against the ATC, which added impetus to Stilwell’s ground campaign through the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys with the ultimate prize being Myitkyina.

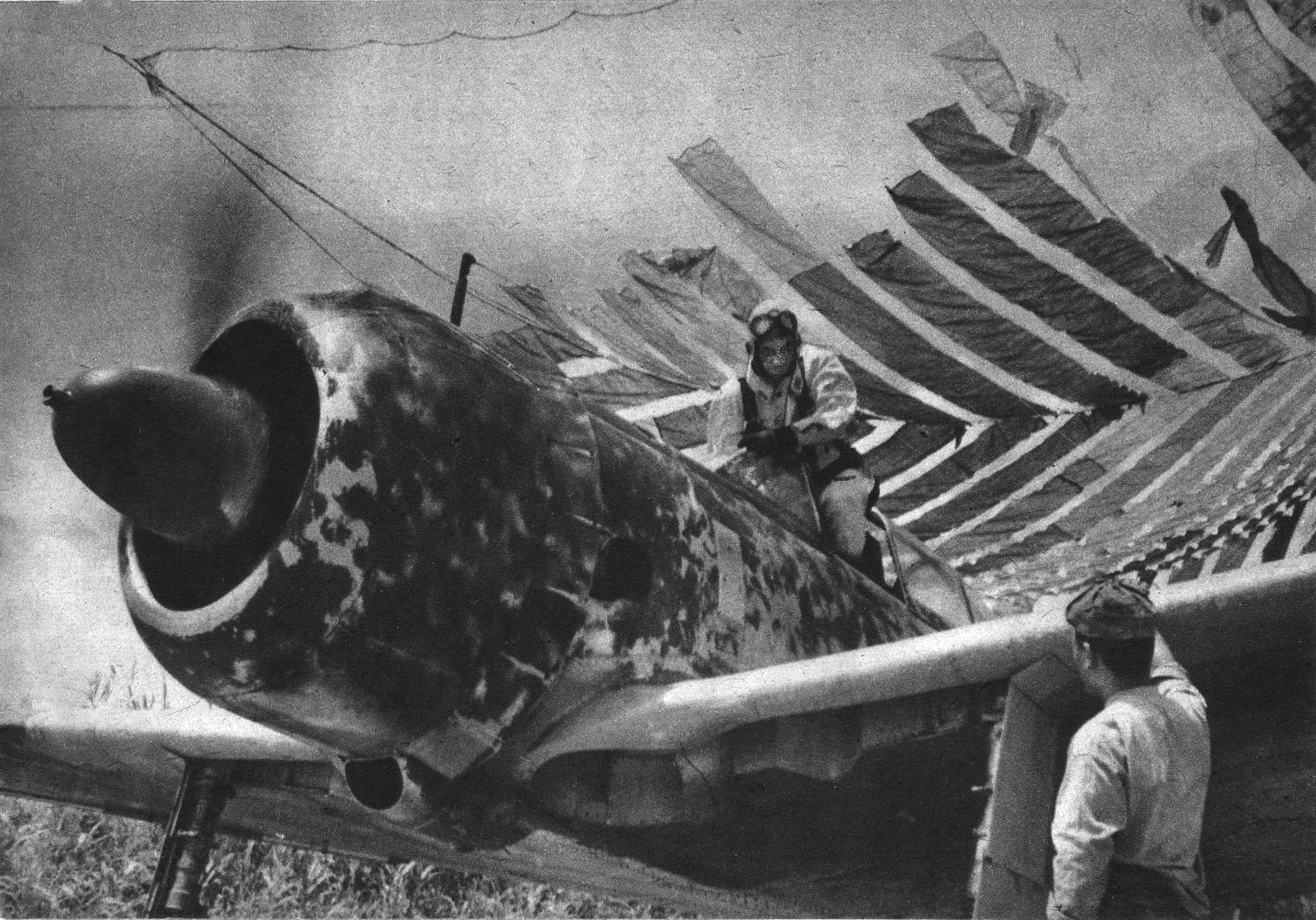

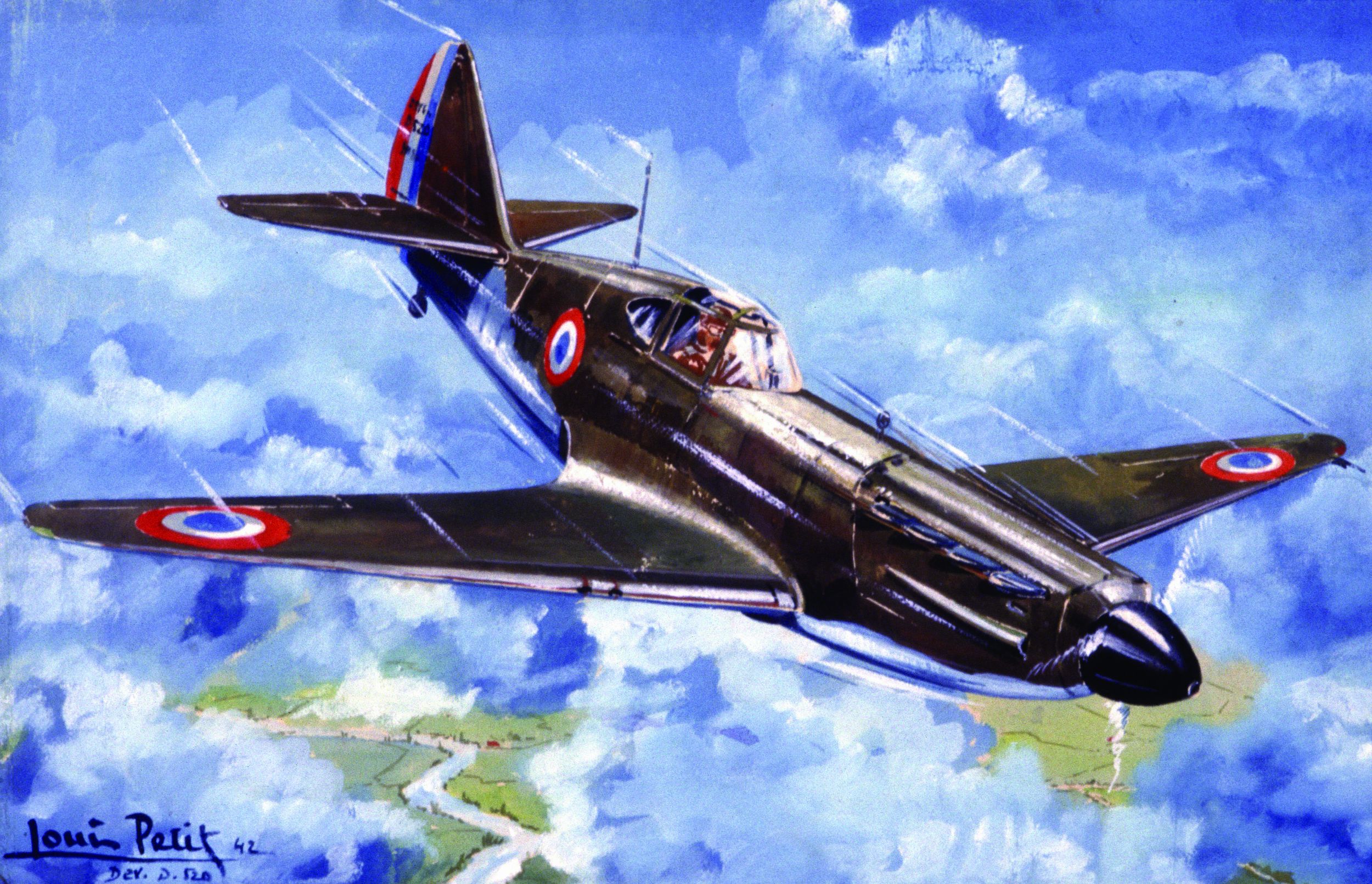

In the autumn of 1943, the air defense of Burma was charged to the IJAAF’s 5th Air Division, which contained, among others, the 50th and 77th Fighter Sentai in its 4th Air Brigade and the 64th Fighter Sentai in the 7th Air Brigade. A Japanese sentai was the equivalent of a U.S. squadron, consisting of roughly 25 planes. The 5th Air Division had scores of forward airstrips and possessed a few counterbalancing advantages. Its rear areas were well out of reach of all but the heavy Allied bombers, of which there were too few to neutralize Japanese bases. Defense against Japanese fighters, initially the Nakajima Ki-27 Nate and later the Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar, was poor because the Japanese concealed their airfields from aerial photography and even from Kachin scouts by hiding their planes in holes in the ground covered with sod.

The Ki-43 was considered the Japanese Army’s best fighter in terms of maneuverability and speed, but it lacked an aerial punch, being lightly armed with only two 12.7mm machine guns. Also, it had no pilot armor, self-sealing gas tanks, or starter motor. The Ki-43 was developed in 1937 when the Japanese Army decided to produce a fighter with a retractable undercarriage to succeed the Ki-27.

This newer fighter went into service in June 1941 and proved successful despite its light armament. After encounters with more advanced Allied fighters, armor and self-sealing fuel tanks were added. The Ki-43 saw action across the Pacific and toward the war’s end was used in kamikaze attacks against Allied warships and bombers. The Ki-43 was deployed in greater numbers than any other Imperial Army fighter and was second only to the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Mitsubishi A6M Zero in terms of sheer production numbers. Vital for its role as a Hump interceptor, it had a service ceiling of 36,750 feet but a limited range of 1,095 miles.

Airmen of the ATC were of a very special caliber, largely due to the operational constraints placed upon them by the Hump route. Prior to 1944, these crews often flew 16-hour shifts sometimes comprising three round trips in a day. Their airfields were crude by construction standards.

The men of the ATC used a variety of planes, but the workhorse was the newer C-46, which was prone to engine failure, plagued by carburetor icing, and often overloaded when flying above its maximum ceiling of 27,600 feet. The Commando had a crew of four and was unarmed. This aircraft was designed as a replacement for the C-47 transport, which was better known by its civilian title, the Douglas DC-3. The C-46 was able to carry cargo at greater altitude than any other Allied twin-engined transport aircraft during the war.

The C-46 was promised for delivery in July 1942 to assist in supplying China after the fall of Burma to the Japanese in April. The C-46 was said to be a more reliable, heavier fitted variation of the older two-engine C-47 transport that the Army Air Corps had been using since the war’s beginning. Capable of carrying nearly twice the load of the C-47, a C-46 could also operate at altitudes higher than the 24,000-foot ceiling of a C-47, more reassuring to the Hump pilots sometimes scraping the Himalayan mountaintops.

Due to delays in the production of the C-46, the ATC had to rely on the older C-47s along with scores of refitted American Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers, rechristened C-87s for cargo, and the C-109, a tanker version of the C-87, as fuel carriers. Even after the delivery of the newer transports, many of the C-46s were found to have structural flaws.

As the ATC began cobbling together an air fleet, the airlift began to show signs of improvement by September 1942 with over 400 tons of supplies delivered to China. The IJAAF observed this greater delivery rate to China, and its Burma-based air arm was waiting for the end of the monsoon season to contest the Hump route.

The Japanese air sentai, staged out of bases in southern and central Burma, began bomber attacks against American transport bases in Assam as well as fighter attacks against airborne transports. However, with the Japanese bases being nearly 500 miles from the Hump’s flight path, the range limitations of the Ki-43 fighter of 1,000 to 1,100 miles became all too evident. To lengthen their time over targets or within the transport route, it became apparent that the Ki-43 fighters would have to recover to a more northerly staging base, like Myitkyina, to refuel.

It had been an IJAAF tactic to strike at U.S. air bases in Assam because they were easier to attack than solitary cargo aircraft in transit, which without radar would be extremely difficult to identify solely by visual recognition. As the numbers of ATC transports flying the Hump route increased to a few dozen flights a day by 1943, the 5th Air Division tried to interdict these sorties with aerial fighter attacks.

Thus, the 5th Air Division was now committed to attack the Hump route with aerial combat as part of the IJAAF plan to regain air superiority against the Allies in the skies over Burma. As a harbinger of this new air offensive, an unarmed C-87 transport was shot down on August 9, 1943, as two radio operators heard the crew state that they were under attack and that they were taking evasive action in the clouds to avoid the Ki-43 fighters. They were never heard from again.

On October 13, the Japanese 50th Sentai launched Operation Tsuzigiri (Street Murder). Eight Ki-43s were sent to Myitkyina to begin hunting transports. Japanese sources claim that 50th Sentai aircraft shot down three transports on October 13, while U.S. records comfirm only two. Moving their base forward to Myitkyina reduced the range from base to target for the Japanese aircraft, theoretically allowing them longer time in the air to engage the transports.

Aircraft of the 50th Sentai attacked again a week later and downed a single C-46. Three days later, another transport was shot down by Ki-43s.

General Chennault did not remain idle for long, dispatching his 308th Bomb Squadron of B-24s to mimic the flight pattern of their unarmed C-87 counterparts while hoping to lure the Ki-43 fighters into aerial combat. Some sources claim that these B-24s, wolves in sheep’s clothing, shot down eight Ki-43s in a single day and as many as 18 over a three-day period.

Although the renewed offensive had lasted only two weeks, the American air combat response and the consequent IJAAF fighter losses ended Operation Tsuzigiri. Officially, Japanese commanders decided that the 50th Sentai could not spare missions that downed only a handful of U.S. transports.

Some intriguing observations have emerged from the geographical pattern of cargo transport losses during Operation Tsuzigiri. First, the five transports shot down during the two-week interval clearly showed that they were all from 50 to 100 miles south of Fort Hertz, a remote British outpost in northeastern Burma. This was in direct contradiction to the recommended safest air route for the transport crews in both 1942 and 1943, which was 30 to 40 miles north of Fort Hertz to avoid Japanese fighters. Second, the Japanese fighters were all staged out of Myitkyina.

Why had the American transport crews flown such a perilous route rather than the northerly arcing one? It was the most direct route possible between the Hump depots in Assam and the southwestern Chinese air terminals. Apparently, the transport pilots flew the northerly route only when it was deemed mandatory because of a Japanese air threat.

Since these crewmen knew that Ki-43s could not maintain a combat presence for long intervals because of their relatively short range, the Hump pilots were gambling against only a potential Japanese fighter threat rather than the certain one posed by the high Himalayan mountain barrier of northern Burma on the northerly arc.

Thus, when Ki-43 fighters were suddenly relocated to Myitkyina, they shot down several transports and drove the remaining ATC crews to the more treacherous northern route leading to more wasteful fuel consumption, reduced loads, and longer flight times.

Only the elimination of Myitkyina as a Japanese fighter base would enable the ATC pilots to resume the more southerly route, and commanders in and out of the CBI realized that this compelled Stilwell to launch his offensive for Myitkyina and the simultaneous construction of the Ledo Road in earnest in the late autumn of 1943. n

Jon Diamond is a practicing physician in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has completed recent Osprey Publishing Command books on Field Marshal Archibald Wavell and the Chindit organizer, Major General Orde Wingate.

My Dad, William H. McClare was a liaison pilot for OSS Detachment 101 and earned a Distinguished Flying Cross at the Battle for Myitkyina. He often spoke of the bravery exhibited those flying over the “Hump”