By Steve Sommers

About 30 years ago, my wife and I were walking around a big antique toy market on a county fair site. There were sheds and barns and tents and the backs of station wagons filled with every sort of doll and truck and train imaginable. Of course, I was looking for toy soldiers: Heyde if possible. And there in an open shed I found a dream; all the pieces were still tied down in a two foot, square burgundy-colored Georg Heyde and Company box. It was a U.S. Navy zeppelin set.

In the box there were dozens of figures: holding ropes, carrying cans, and waving signal flags. There also were pilots sporting brown flying suits, an officer looking through a spyglass, and even a sailor messenger on a bicycle. In the middle of the two-tiered box was a great tin zeppelin with a flying American eagle painted on the side and “U.S. Navy” scrawled below. The asking price was more than I had in the bank; in fact, it was more than I thought any toy soldier collector would be willing to pay, but somehow the set disappeared. I have never seen another one exactly like it, and I have often looked.

I may have been destined to be a toy soldier collector. One day when I was about five or six, my dad appeared with a large, old, square cardboard box; it had a picture label showing an American Flyer train. Inside I discovered a tin railroad station, a big green tunnel, lights and signals, many sections of track, a transformer, a black electric engine, and brown tin passenger cars. Dad said his family had moved frequently; as a result, this box was the only toy left from his childhood. I picked up one of the cars and gave it a shake. It rattled. I slid back the car roof, peered inside, and saw two play-worn kneeling Scots, one with a broken rifle and the other with missing arms. Despite their condition, I was hooked. I liked that train, and I owned several 1950s Lionel sets, but it was toy soldiers that I loved the most.

Like those kilted, white-helmeted highlanders, more than half of my boyhood soldier collection was hollow-cast lead, manufactured by Britains. Britains’ figures dominated the market for enthusiasts in the past century. The rest of my army was made by Britains’ competitors and by three-inch American Dimestore soldier makers. Britains were painted in bright uniforms of all nations and sold with several figures to the box. For a dime each, three-inch khaki troops by Manoil or Barclay could be individually plucked out of a sales tray at the corner store. I had both types. My mom made me play with my Britains inside on the rug, but the dimestore soldiers were made for backyard trenches and attacks with rocks or even BB guns.

Most of my dime store figures were killed in action, but I kept my Britains on the shelf and then stored them for 20 years. When I was a kid, though, it was my dad’s stories of his childhood wishes that turned me into a dreamer of Heyde figures. Heyde figures were the two-inch, solid cast, animated toys of his childhood. My dad told me about the Heyde soldiers he wanted but could never afford. He recalled that the figures were sold with accessories that formed miniature dioramas, such a pontoon bridge under construction, a military encampment with tents and tables, a zoo with tiny buildings, and a frozen pond with children ice skating.

I pictured all of that and more in my imagination. Much to my frustration as a child, I was never able to find a single figure. I later learned that thanks to World War II and the U.S. Army Air Forces, the Heyde Company in Dresden did not survive the war.

As an adult, I studied history, moved back to Chicago, and met a group of people in the Military Miniature Society of Illinois. Most of them sculpted or painted miniature figures. They meticulously recreated uniforms and parade or battle postures to a high degree of accuracy. I tried my hand at connoisseur figure painting, but soon I realized that along with a few others in the club, my first love was still toy soldiers. At first I collected Britains’ figures; their emphasis was clearly on parades of accurately detailed uniforms. Action was generally limited to running horses and soldiers shooting in dress uniforms. Soon, however, I discovered that with some digging and a little help, Heyde’s more toy-like, animated figures, old and battered or mint in the box, could still be found.

Today, an adult might have a handful or a boxful of toy soldiers left over from childhood or collected as a reminder of the past. Most collections range from a few hundred to a thousand or more figures; and these collections probably have a focus beyond simple nostalgia. Soldier collecting in the 20th century perhaps can be traced back to two books by H.G. Wells: Floor Games (1911) and the better known Little Wars (1913). These books established the framework for one part of the toy soldier collecting hobby: wargaming. Although Wells was British, his first book was partially illustrated with photographs and drawings of German-made Heyde figures alongside Britains’ figures, toy trains, and blocks for scenery. So, between imaginary battles an adult enthusiast might line his troops in mantelpiece parade or create a temporary diorama on a shelf. After all, they were too much fun to simply store in a box.

Then as now, the military history enthusiast might collect figures to arrange in a cabinet or enhance a collection of books, or as a reminder of regimental or national history. Another common approach by figure collectors is to try to acquire everything in the company’s catalog as stamp collectors do. Or maybe it is collectors who simply love one particular maker. I probably collect Heyde figures for all of these reasons.

When I was a kid, television and movies stimulated my collecting. My imagination gave me a redcoated British square repelling Zulus; Britains also supplied me with hollow-cast French legionnaires fending off charging Arabs. As a child and as an adult collector, the options seem endless. As with any other type of collecting, though, it is possible to simply run out of gas. Many advanced collectors manage to keep going by broadening the scope of their collecting or upgrading the quality of their troops. For example, they might request only mint condition soldiers in their original box.

How big can a soldier collection get? I knew a lifelong collector, with no limit to his interests, but with a modest income. Still, when he retired to the southwestern United States, he needed a moving van to transport it all.

What is the value of a collection? Again, type of figures, age, condition, and quality determine the financial worth of individual figures or sets. For example, a single Heyde figure in the most common 48mm scale might range enormously from a used soldier that has been played with going for a dollar or less to an in-the-box mint set selling for several hundred dollars. About 25 years ago, I heard of a fellow who traded a 1930s sports car for a collection of Napoleonic French soldiers made by Mignot. Within a year, the man with the soldiers had lost interest in the toys, but it turned out to be an even deal. Apparently, the fellow with the car blew up its engine. I supposed that made it a good trade.

I like Heyde figures for many reasons. Ironically, one is that Heyde production is not well documented. For Britains, it is the opposite case. Britains are exceptionally well catalogued from their start in the 1890s to the present. There are good American books on Britains, such as those written by Joe Wallis. But when I began looking for Heyde, there was mystery about it; discovery is still part of the fun in searching for these German-made toys. In 2003, a Heyde enthusiast, Markus Grein, wrote the first book, With Heyde Figures Around the World, on the history of the company. Even more recently, T. Borges and F. Winckel wrote Heyde-Hunters, a picture book that shows some of the best of the company’s sets.

Although Britains produced figures showing troops from many nations, its lead soldiers were most often marching on parade. One of Britains’ largest and longest made sets was the formal changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace. Heyde, in addition to producing some large sets of parade troops, made a great many sets of figures in action. They were intended for creative play or display. With Heyde, a boy or man might simply have fun recreating scenes from the siege of Troy to the trench warfare of World War I. Heyde supplied them both.

I continue to buy Heyde figures at auctions and from dealers at antique toy soldier shows. I swap with fellow collectors, and I hope for a good find at an antique shop. A few years ago on a trip to France, I found a great set of Heyde Egyptians in chariots fighting Nubian warriors. They were in the window of an art and militaria shop; when I asked the woman behind the counter for the whole group, she had to telephone the owner for the price. When the call was returned, I was amazed that they were asking less than I expected. That does not happen often, I am sorry to say.

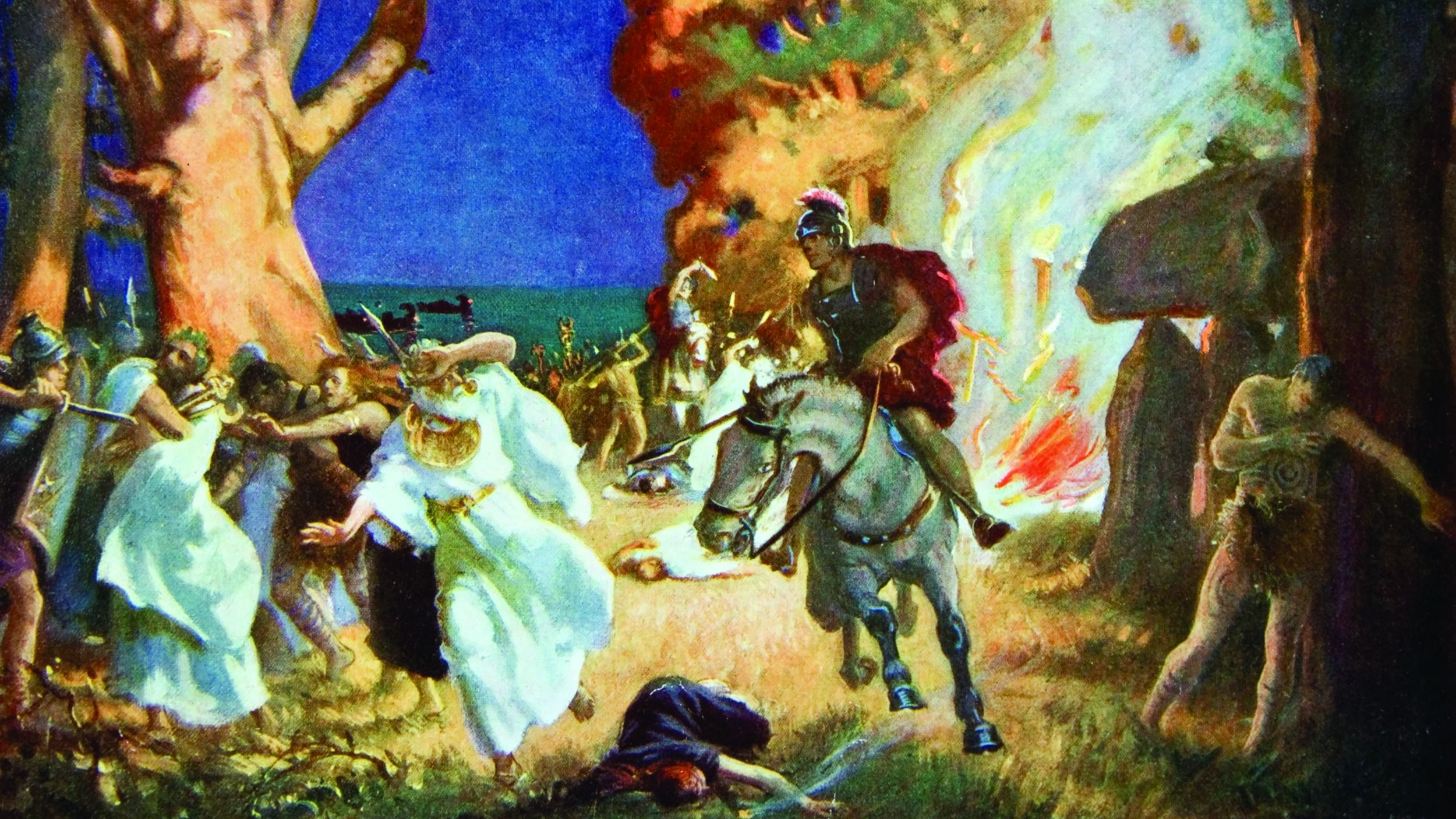

The Egyptian set is still in my collection that I have been building for more than 30 years. I have concentrated on ancient warfare and the past 200 years of history. I have several sets depicting the early period. There is the Taking of Troy with its sloping walls, Greek temple, Trojan horse, and characters right out of Homer’s Iliad. Heyde’s Alexander the Great set centers on a mammoth war elephant. The Roman triumphal procession of Germanicus also includes an elephant along with chariots and dozens of figures in ceremonial dress. Medieval knights occupy a castle by Gottschalk, the well-known dollhouse maker. I am lucky enough to have buffalo hunt sets in two sizes, each complete with cowboys, Indians, and a stagecoach.

Although covering all of Western history, Heyde specialized in figures of European wars right up to World War I, as well as 19th-century empire building. Heyde offered Franco-Prussian War battles, such as Sedan or the siege of Paris. World War I was the theme for many sets: trench fighting, almost comical battling tanks, pontoon bridge building, and communication units with Morse code keys or an electric light.

set replicates warfare between Egyptians and Nubians.

Heyde also produced an Arab caravan and French legionnaires fighting in North Africa. The company even made little lead battleships that were much too small for their figures to sail. In nonmilitary figures, Heyde cast children playing in parks in summertime and wintertime, red-jacketed huntsmen chasing a fox, and fairy tales, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

Many nations and scenes were in Heyde’s regular offerings; if not, specific sets could be special ordered. Heyde even made an airport and an arctic Little America set, which was incongruously complete with both penguins and polar bears. These and other Heyde super sets had tin buildings that anticipated by four decades the MARX plastic playsets of the 1950s and 1960s.

Why do I collect Heyde figures? They are historical, inventive, and simply fun. Other toy soldier makers covered some of the same themes, but with Heyde there was a special quality of animation and variety and a magical toy-like look and feel.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments