By Mike Phifer

Major General James Ewell Brown Stuart was in all his glory. It was June 8, 1863, and the Confederate cavalry commander was putting on a grand review of his horse soldiers on a plain west of the Rappahannock River near Brandy Station, Virginia, for none other than General Robert E. Lee. In fact, this was Stuart’s third grand review since May 22. The first two had more pomp and ceremony and concluded with a mock battle. The third review was more hastily put together for Lee, who had been invited to the second review but missed out.

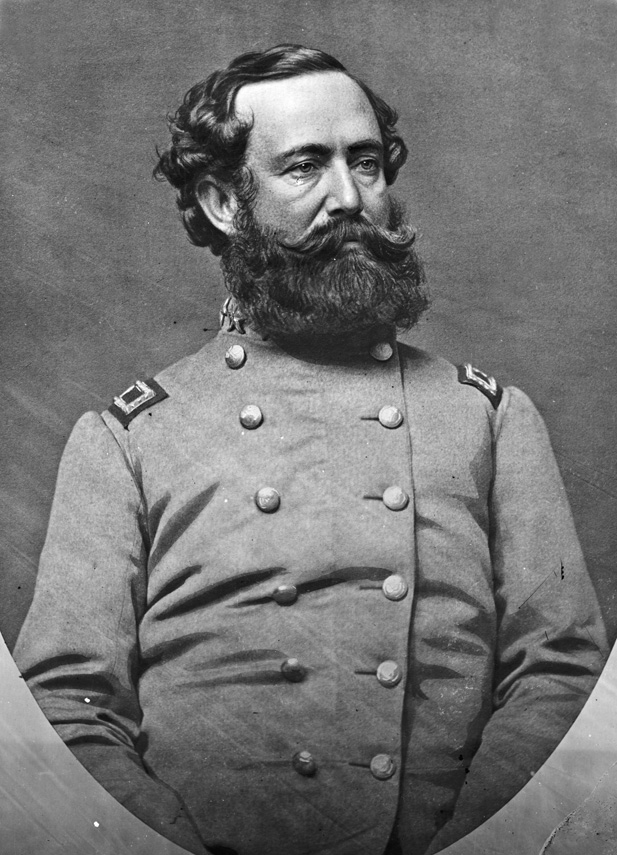

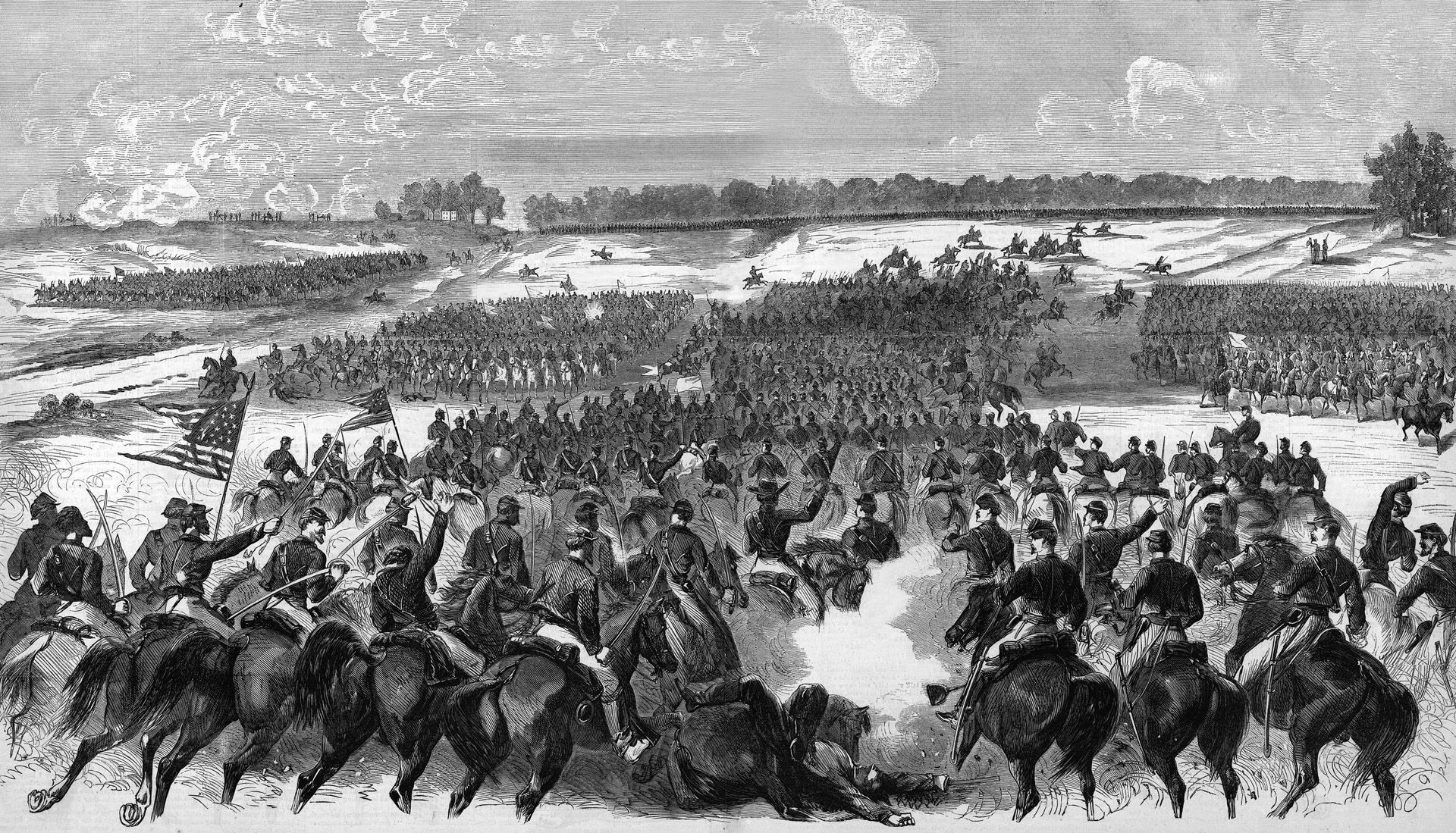

Stuart’s 22 regiments of horsemen were lined up in double ranks that stretched for three miles. It was an impressive sight, and Stuart had good reason to be proud. His cavalry was at its zenith, boasting five brigades of horse soldiers and two battalions of horse artillery numbering 9,536 troopers and 756 officers. With plans to take the war north, Lee had reinforced Stuart with a brigade of cavalry under the command of Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson from North Carolina and Brig. Gen. William “Grumble” Jones’s brigade from the Shenandoah Valley. Stuart was happy to have the reinforcements, but not with their commanders. He thought Robertson “the most troublesome man in the army” and had been glad to see him reassigned to North Carolina. Stuart also disliked Jones, a feeling that was returned by the rough-talking, hard-fighting cavalry officer.

Besides seeing his cavalry command increased in strength, Stuart had spent almost a month in Culpepper County, where he had been sent to protect the Army of Northern Virginia’s rear from Federal cavalry and take advantage of the good grazing land there. While there he also resupplied his regiments, got fresh mounts when possible, and drilled his men.

After inspecting the troopers, Lee took up position on a low rise and watched as almost 10,000 sabers flashed in the sunlight, colors flying as the squadrons passed him in columns of four. When the review was finally over, the tired troopers rode back to their respective camps near Brandy Station.

Colonel Tom Munford, who was briefly in command of Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade, as Lee’s nephew was laid up with rheumatoid arthritis, encamped for the night at Oak Shade Church near the Hazel River, a tributary of the Rappahannock. Brig. Gen. William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, Robert E. Lee’s son, meanwhile, took up position at Welford’s Farm, while Jones’s brigade encamped near St. James Church along with Major Robert Beckham and the famous Stuart’s Horse Artillery Battalion.

Brigadier General Wade Hampton, one of the richest men in the Confederacy, bivouacked his brigade between Fleetwood Hill and Stevensburg along with Robertson’s brigade. Stuart, meanwhile, headed over to his headquarters on Fleetwood Hill. This scenic terrain was an elevated ridge that commanded the surrounding rolling country and the roads leading north and south from Brandy Station.

Stuart was happy with the day’s pageantry and prepared to move his men out the next day as they were to screen Lee’s army as it began to shift west and then head up the Shenandoah Valley for an invasion of the North. Jones, though, was not pleased with the day’s events and commented: “No doubt the Yankees, who have two divisions of cavalry on the other side of the river, have witnessed from their signal stations, this show in which Stuart has exposed to view his strength and aroused their curiosity. They will want to know what is going on and, if I am not mistaken, will be over early in the morning to investigate.” He was right.

For some time, Union General Joseph Hooker had been receiving reports about Stuart’s presence in the Culpepper Court House vicinity. Colonel George Sharpe, Hooker’s chief of intelligence, believed the Rebels intended to launch a large cavalry raid. Hooker decided to strike first.

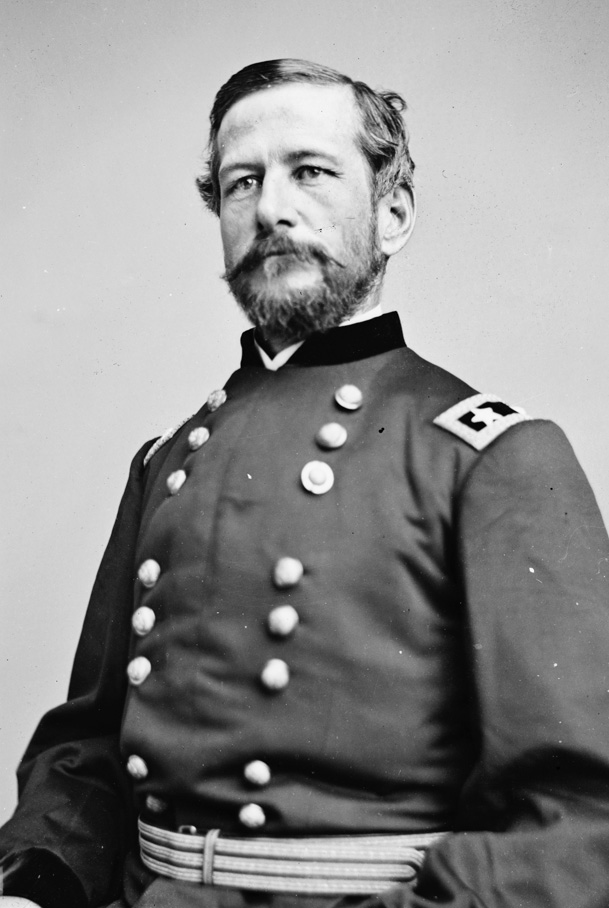

On June 7, Hooker ordered Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, his cavalry commander, to divide his force and cross the Rappahannock River at Beverly and Kelly’s Fords and “disperse and destroy the Rebel force assembled in the vicinity of Culpepper.” The Federal horsemen were also to destroy the enemy’s “trains and supplies of all description” to the best of their ability. If they should be successful in routing the Rebels, they were to pursue them vigorously as long as it was to their advantage.

It was a tall order for the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry. By the third summer of the war, Union cavalry was finally reaching parity with Confederate cavalry. When the war broke out, the North was at a disadvantage for qualified cavalry officers as the majority of those serving in the regular army resigned their commissions to fight for the South. In the first half of the war, the bluecoated cavalry generally suffered from a lack of comfort and experience in the saddle. In contrast, their Confederate counterparts, who had relied heavily on horses for personal transportation before the war, had brought their own mounts when mustered into units. The result was that the Union cavalry mostly had been outfought and outridden by its Rebel adversaries.

The organizational structure of the Union cavalry during the first part of the war also put it at a distinct disadvantage. Rather than being organized in a separate cavalry corps, individual regiments were attached to infantry commands for use as scouts, couriers, and escorts. Such an approach completely nullified their use for raids and long-range reconnaissance.

In contrast, Stuart used his cavalry for large-scale actions that effectively merged reconnaissance activities with disrupting enemy operations during the Peninsula and Second Manassas campaigns. Having circumnavigated the Union Army in the East during the Peninsula campaign, Stuart repeated the feat after the Antietam campaign with his famous Chambersburg Raid in October 1862. Stuart’s ability to ride around the Union Army was deeply humiliating to the Union cavalry units serving in the East.

Under Hooker’s command things had greatly improved for the Federal horsemen as “Fighting Joe” made sure they received better training, equipment, and horses, weeded out poor officers, and most importantly grouped the horse soldiers into a corps. The newly created cavalry corps had done well in its first raid into Culpepper County at Kelly’s Ford in March but did less well in a raid behind Rebel lines during the Chancellorsville campaign in May. Now the Federal horsemen were anxious again to prove their mettle and skill.

Before the bluecoats mounted up and rode out on June 8, they refilled their cartridge boxes, were issued three days worth of rations, and saw to their horses. Soon 9,000 horse soldiers, divided into three divisions, were in the saddle and on the move for their destinations. Marching along the dusty roads in support of the cavalry were 3,000 blue-coated infantrymen. These handpicked regiments made up two brigades and were among the best marching and fighting soldiers of the Army of the Potomac.

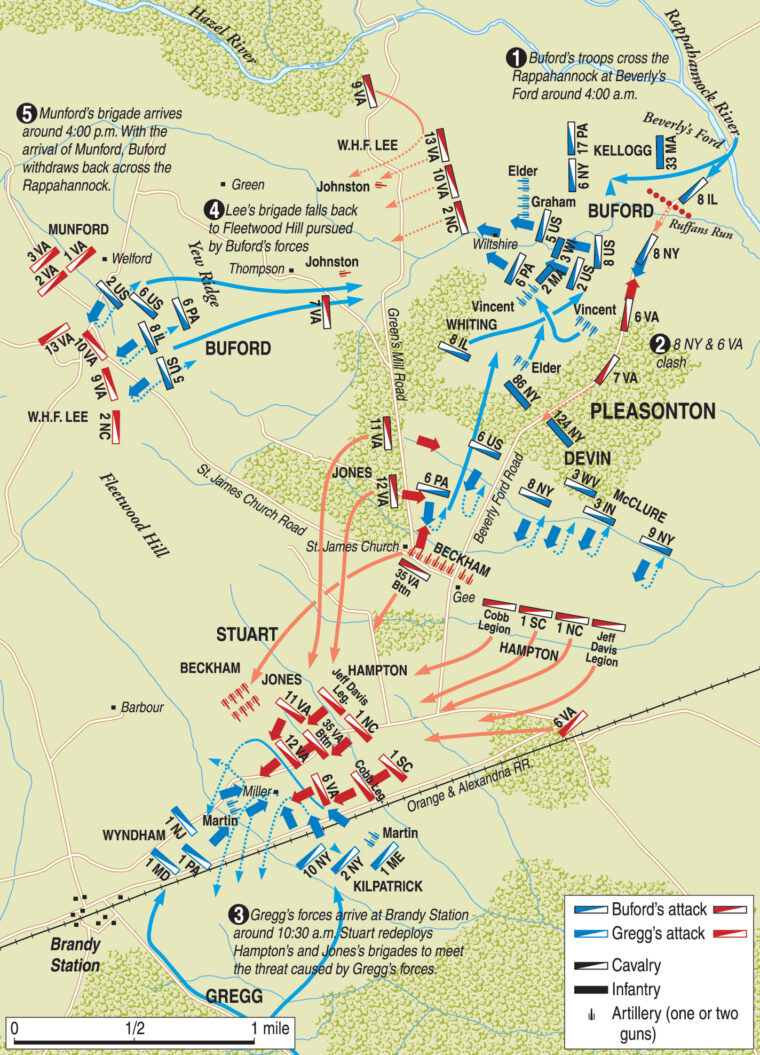

The Federals’ plan to thrash Stuart’s cavalry was to have Brig. Gen. John Buford take his 1st Cavalry Division and the Reserve Brigade across the Rappahannock at Beverly Ford and move on to Brandy Station. Accompanying him was a brigade of infantry under Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames and some horse artillery. Buford’s force made up the right wing of Pleasonton’s plan, and the cavalry corps commander would travel with this wing himself.

At Brandy Station, Buford was to be joined by Brig. Gen. David Gregg’s 3rd Cavalry Division, which was to cross the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford, located about eight miles below Beverly Ford. Also crossing Kelly’s Ford as part of Gregg’s left wing was the 2nd Cavalry Division under Frenchman Colonel Alfred Duffie and an infantry brigade under Brig. Gen. David Russell. Once across the Rappahannock, Duffie was to take his division and ride to Stevensburg to protect Buford’s and Gregg’s left flank as they headed to Culpepper and attacked the Rebel cavalry. Only as the Union cavalrymen were to brutally learn, Stuart and his horse soldiers were not at Culpepper, but rather five miles closer at Brandy Station.

After a hot, dusty ride, Gregg’s 3rd Cavalry Division reached Kelly’s Ford and encamped about a mile from the ford after dark. With the Rebels nearby, extra precautions were taken, no fires were lit, and the men ate a cold meal. Gregg ordered that the horses were to remain saddled and bridled. The troopers, trying to catch some sleep, had to loop the reins around their arms.

Around midnight, Buford’s men bivouacked about a mile or two above Beverly’s Ford out of sight from Rebel pickets. With no campfires allowed, the men dined on cold ham and hardtack before grabbing a couple of hours of sleep. At 2 am the horse soldiers were quietly awakened from their short slumber and ordered to mount their horses. Once mounted, they rode toward the ford.

A gray dawn began to appear, casting strange shadows on the landscape when the 1st Cavalry Division reached the ford, which was shrouded in a thick fog. Sitting on his gray horse smoking a pipe, Buford watched as his troopers splashed into the 31/2-foot-deep ford and crossed over in columns of four around 4:30 am. Alabama born Colonel Benjamin F. Davis led the 1st Brigade across the ford first with the 8th New York Cavalry spearheading the way.

Rebel vedettes spotted the bluecoats and thundered back to the picket reserve, their revolvers blazing to sound the alarm. The 30 sleepy-eyed men who made up the picket reserve from the 6th Virginia Cavalry of Jones’s brigade quickly mounted up. Their commander, Captain Bruce Gibson, dispatched two men to gallop back to tell Jones of the Yankees coming. “Keep cool, men,” Gibson told his pickets, adding, “and shoot to kill.” He then led the small band of horsemen forward to slow down the Federal onslaught.

Gibson’s pickets let loose a volley at close range into the advancing 8th New York Cavalry, emptying a number of saddles. The Federal advance was momentarily turned back, but the main body soon came up, forcing Gibson and his men to fall back. Davis’s brigade pressed them hard toward the camp of Stuart’s Horse Artillery about a mile and half from Beverly Ford. Pushing through the trees and to an open plateau, the bluecoats spotted the Rebel artillery in an open woods.

Yankee bullets zipped in over the blankets of the Confederate artillerymen. The men quickly scrambled to their feet and dashed for their 600 horses and mules that were pastured nearby. While most of the men harnessed their animals and limbered them up, quick-thinking Captain James Hart of the Washington Artillery of South Carolina rolled one of his guns out onto the road with the help of a handful of men. The Blakely gun then began hammering the Federal horsemen with canister. Another gun was soon rolled into action and added its firepower against the Yankees, buying the Confederate artillerymen precious time to get their guns to safety.

Major Cabell E. Flournoy, commander of the 6th Virginia, quickly thundered onto the scene with 150 horse soldiers, some of them without coats and saddles. They pushed past the retreating Confederate guns and crashed into the 8th New York. Sabers slashed and revolvers crashed in the bloody and fierce fight, which initially pushed back the 8th New York. Bluecoat help soon arrived, and outnumbered and suffering about 30 casualties, Flournoy was forced to fall back.

Lieutenant R.O. Allen of the 6th Virginia quickly turned his horse around when he spotted Colonel Davis about 75 yards ahead of his men. Davis was turned in the saddle waving his men onward yelling, “Stand firm, 8th New York!” Sensing something wrong, he turned to see Allen coming toward him. Davis swung at Allen with his saber, but the Confederate swung to the side of his horse and missed the blow. Then Allen fired his revolver, putting a bullet into Davis’s brain and killing him.

The 7th Virginia Cavalry had arrived along with Jones and entered the fray. While the blue and gray horsemen attacked and counterattacked along the Beverly Ford Road and surrounding woods, it was becoming clear to Buford and Pleasanton that the enemy cavalry stood between them and Culpepper Court House. The 8th Illinois Cavalry of Davis’s 1st Brigade, now under the command of Major William McClure, hit the two Virginia cavalry regiments hard, managing to finally push them out of the woods.

With Hart’s two guns helping to cover their retreat, Stuart’s Horse Artillery took up position on a ridge near Emily Gee’s brick house and east of the St. James Church. In front of the Rebel guns lay about 800 yards of open terrain to the southern edge of the woods, where the 8th Illinois soon made its appearance and came under Confederate artillery fire. Then the 12th Virginia Cavalry of Jones’s brigade slammed into the Federals. The bluecoats managed to drive off the Rebels only to be hit by two more units from Jones’s brigade, the 11th Virginia Cavalry Regiment and the 35th Virginia Cavalry Battalion. The Illinois boys were quickly reinforced by the 8th New York and 3rd Indiana Cavalry of their own brigade. The Rebels eventually got the worst of it and were forced to fall back near the artillery holding the ridge.

Back at Fleetwood Hill, Stuart became aware of the fighting at Beverly Ford when he heard the gunfire and had been informed of the Yankee’s crossing the ford by a hard-riding courier dispatched by Jones. Stuart ordered his camp taken down and the headquarters and supply wagons sent to Culpepper Court House. Couriers were sent to Hampton, Rooney Lee, and Munford to ride toward the sound of the guns. Orders also were sent to Robertson to watch the other fords, especially Kelly’s Ford.

With Rebel resistance stiffening, Buford brought up the two infantry regiments of Ames’s brigade. He ordered the 124th New York Infantry to take up position at the edge of the woods on the west side of the Beverly Ford Road, while the 86th New York Infantry was put on the east side of the road. To the left of the 86th, most of the 1st Brigade, except the 8th Illinois, took up position. Held in reserve was the small 2nd Brigade. Buford’s artillery was also brought up and had some difficulty deploying due to the trees.

Buford ordered Major Robert Morris Jr., commander of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry of the Reserve Brigade, to clear the woods of any remaining Rebel skirmishers. As Morris move forward with his men, any remaining Rebels soon scrambled back to their own lines. Emerging at the edge of the woods, Morris led his men in a charge across the open ground toward the Confederate guns and cavalry near the St. James Church.

“We dashed at them,” recounted an officer in the 6th Pennsylvania, “squadrons front with drawn sabers, and we flew along—our men yelling like demons—grape and canister were poured into our left flank and a storm of rifle bullets on our front.” As the cavalrymen galloped toward the Rebels’ guns, they had to leap three ditches, which sent some riders and mounts crumbling into a heap. Morris’s horse went down in one of the ditches, hit by canister, and the major was captured. Heavily outnumbered, the bluecoats fought desperately with their sabers and pistols, some managing to reach a Confederate battery before the 35th Virginia hammered into their front, while the 11th Virginia and 12th Virginia hit their right flank. Seeing the desperate situation the Pennsylvania boys were in, the 6th U.S. Cavalry of the Reserve Brigade sent four squadrons galloping to support them.

“Hundreds of glittering sabers instantly leaped from their scabbards, gleamed and flashed in the morning sun, then clashed with metallic ring, searching for human blood, while hundreds of little puffs of white smoke gracefully rose through the balmy June air from discharging firearms,” said a Confederate artillerymen watching the cavalry fight near his gun. The Federals managed to fight their way out and rode hard for the safety of their own lines.

After driving off Rebel pressure on his right flank, Buford secured his line by anchoring his right on the Hazel River and his left along the Rappahannock. Meanwhile, the Confederates were strengthening their own line of defense with the arrival of the bulk of Hampton’s brigade. Stuart, who had arrived on the scene after leaving his adjutant, Major Henry McClellan and a few couriers and signalmen maintaining contact by flags with Confederate headquarters, ordered Hampton’s men to take up position to the right of Jones and the Gee House.

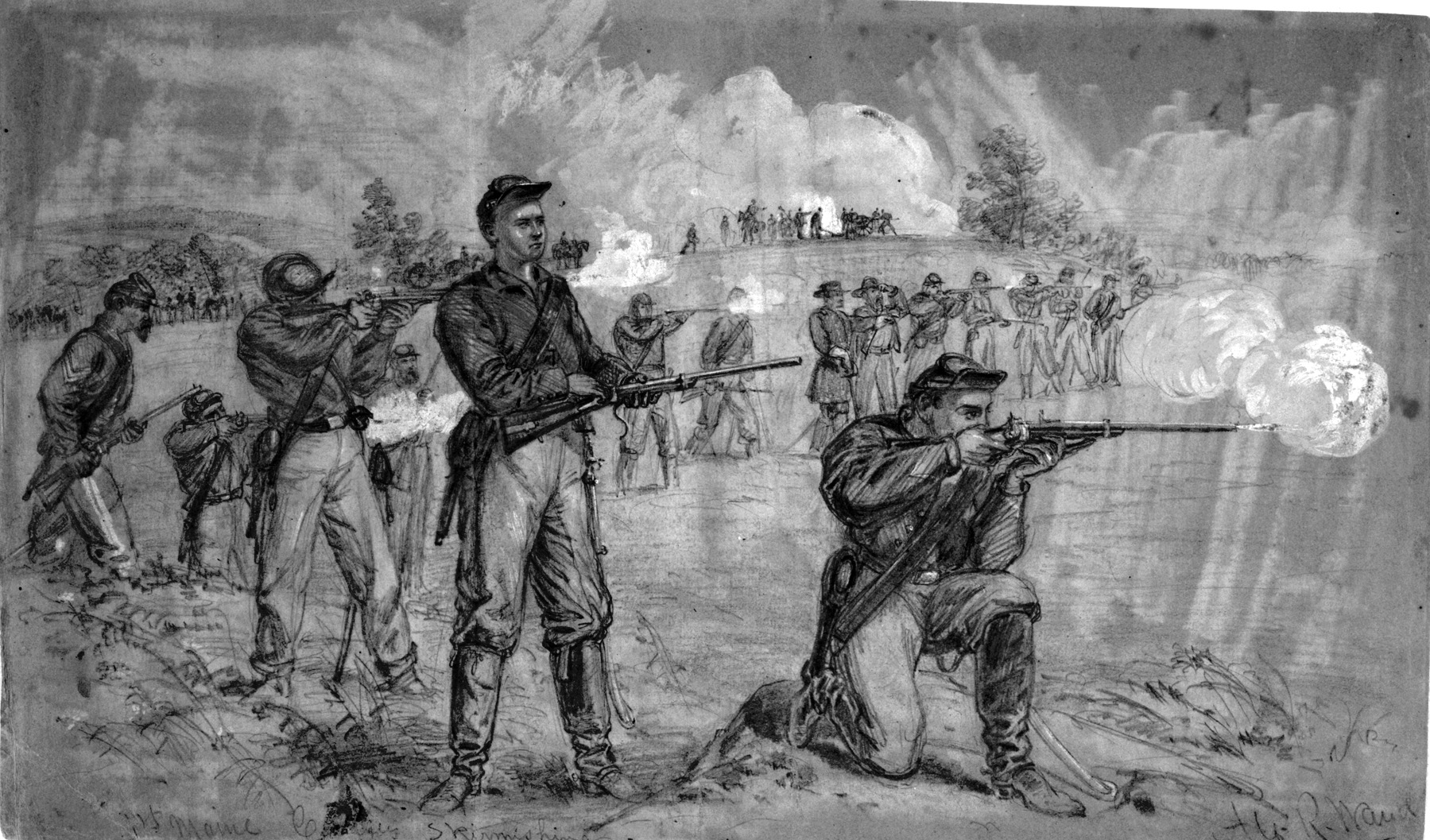

The Confederates went on the offensive. Hampton quickly sent out dismounted skirmishers against dismounted Yankee troopers under Colonel Thomas Devin and spread out infantrymen. A fierce firefight erupted on Buford’s left. Rooney Lee’s brigade, meanwhile, after driving off some Union resistance, had taken up position north of Jones along a stone wall between the Cunningham and Green farms.

With Lee’s dismounted horse soldiers holding the wall and mounted troops in reserve, they had a good field of fire on the right flank of Buford’s position. Buford ordered the understrength 5th U.S. Cavalry to retake the wall. Leaving one squadron to protect a section of Captain William Graham’s battery, two squadrons of dismounted Union troopers managed to capture a portion of the wall and beat back Confederate counterattacks. Running low on ammunition, the Federal troops fell back to help protect Graham’s battery.

Union artillery now opened up on Beckham’s guns. In the artillery duel that erupted, the Yankees got the worse of it, but the firing did allow Buford to reorganize an attack against Lee’s men holding the stone wall. It was thrown back. In the lull that followed, guns were heard booming near Fleetwood Hill. It was now about 11:30 am, and Buford’s men had been fighting for almost six hours waiting for Gregg to arrive. He finally had.

Gregg had a long early morning waiting impatiently for the Frenchman to arrive with his men. Duffie and his 2nd Division had a long, tiring ride for Kelly’s Ford on June 8 and had stopped to rest briefly. Reveille was sounded at 1 am, and the horse soldiers were soon in the saddle again. In the darkness and fog of the early morning, Duffie’s guide got lost, forcing the column to do some backtracking. Finally, Duffie made his appearance sometime around 5:30 am, and Gregg finally got his left wing moving.

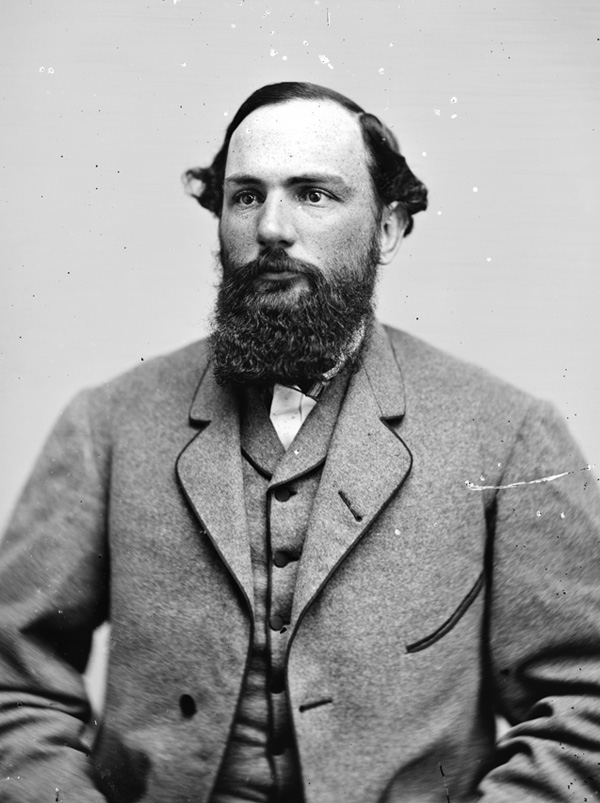

Using two collapsible canvas pontoon boats that Hooker had sent with Gregg’s left wing, a small detachment from Russell’s ad hoc brigade of infantry slipped across Kelly’s Ford. It quickly drove off Confederate pickets and secured the ford. A squadron of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry then splashed across the ford and captured vedettes belonging to Robertson’s brigade. With the ford secure, Gregg’s left wing began crossing the Rappahannock about 6 am. It would take about three hours before all his men had crossed, putting them way behind schedule.

Once across the river, Brandy Station lay only seven miles away by road. The country that lay in front of Gregg was prime cavalry terrain, mostly flat and open. Although the sound of the guns could be heard at St. James Church, Gregg did not ride toward it. Instead, he stuck to the original plan and traveled by road toward Brandy Station. Meanwhile, Duffie’s division was sent toward Stevensburg to protect Gregg’s southern flank.

Besides skirmishing with the Federal infantry, Robertson did little to oppose Gregg’s advance on Brandy Station. He sent word of the Yankee advance and then would do little during the rest of the battle.

Upon hearing of Gregg’s advance, Jones sent a messenger to Stuart to warn him that the Yankees might reach Brandy Station from the south. Stuart replied, “Tell General Jones to attend the Yankees in his front, and I’ll watch the flanks.” Upon hearing this, Jones snapped back, “So he thinks they ain’t coming, does he? Well, let him alone; he’ll damn soon see for himself.”

Leading Duffie’s advance on Stevensburg was Major Benjamin Stanhope with two squadrons of his 6th Ohio Cavalry. Stanhope’s advance pushed into the little town of Stevensburg and soon had its hands full when Confederate cavalry was spotted coming from the north. Stanhope sent word to Duffie of the Rebel advance, but the Frenchman did not speed up his division. Instead, he ordered Stanhope to hold Stevensburg and if forced out to retreat slowly.

Leading the Confederate column of horse soldiers, which consisted of the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry, was Colonel Matthew Butler. Butler had about 200 men and was part of Hampton’s brigade, which had been posted along with the 4th Virginia Cavalry of Munford’s brigade and a lone gun in reserve at Brandy Station. Butler sent Lt. Col. Frank Hampton, younger brother of Wade Hampton, with a small detachment into Stevensburg to establish an outpost and delay the Yankees. Upon reaching Stevensburg, Hampton helped hurry along some of Stanhope’s men, who had evacuated the town.

To block the Yankee advance toward Culpepper and screen Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps encamped about halfway to the town from Stevensburg, Butler deployed his force east of the Stevensburg-Brandy Station road, just outside of town. The wooded terrain of the area helped hide Butler’s weak numbers as his men were spread out over a mile. Butler was soon informed that reinforcements were on the way in the form of the 4th Virginia Cavalry under Colonel William Wickham.

When Duffie arrived around 11 am, he sent in mounted skirmishers to determine the strength of the Rebels. Without orders, Colonel Luigi di Cesnola quickly charged with his 1st Brigade, with the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry leading the way into Hampton’s detachment holding Stevensburg. The Confederates here were overpowered and forced to flee. Lt. Col. Hampton was mortally wounded. The Union horse soldiers soon smashed into the 4th Virginia, which had just arrived and was forming for battle. “It was a regular steeplechase” recalled a Union cavalryman, “through ditches, over fences, through underbrush.” The graybacks scrambled for safety, rallied temporarily, only to retreat again with some of them not stopping until they reached Longstreet’s men.

With his right flank collapsed and fleeing, Butler had no choice but to retreat toward Mountain Run, a small stream with steep banks about three miles south of Brandy Station. Duffie and his men rode into Stevensburg and then headed north on the road that led to Brandy Station. The Frenchman could see Butler attempting to make a stand at Mountain Run. Duffie’s artillery commander, Lieutenant Alexander Pennington, quickly brought his battery into action against the lone gun with Butler. One of Pennington’s rounds smashed into Butler and another officer. Butler was badly wounded, losing his foot, while the other officer died later that night. Butler passed command to Major Thomas Lipscomb, telling him to fight and fall back slowly toward Culpepper.

As Duffie prepared to charge the Rebel position, a courier reached him from Gregg telling him to “return and join the 3rd Division, on the road to Brandy Station.” Duffie was to head back the way he came on the Kelly’s Ford Road and join Gregg at Brandy Station. Gregg was in wild fight at Fleetwood Hill and could use the Frenchman’s help.

Watching the Yankees under Gregg advancing on Fleetwood Hill was Major McClellan, the staff officer Stuart left behind. He knew the Confederates were in serious trouble if the Yankees captured the hill, but as it was he had little at hand to defend the key terrain. After quickly sending a rider to warn Stuart, McClellan spotted a lone 12-pounder Napoleon gun near the foot of the hill. McClellan had the gun’s commander, Lieutenant John Carter of Chew’s battery, bring his artillery piece to the top of the hill beside the Miller House. He then ordered Carter to fire slowly on the column of advancing Yankees.

British soldier of fortune Colonel Sir Percy Wyndham was leading his 2nd Brigade as the advance guard of Gregg’s 3rd Division when Carter’s lone gun fired on his command. Wyndham halted his advance just below the Orange and Alexandria Railroad tracks and deployed his brigade. Possibly fearing the Rebels had set a trap, he sent a message to Gregg and then waited to hear from his commander before advancing. In the meantime, Wyndham ordered up a section of guns from Captain Joseph Martin’s 6th New York Independent Battery, which unlimbered and fired on the Rebel gun.

Carter’s lone gun bought precious time for the Confederates. When the courier from McClellan arrived at St. James Church and informed Stuart of the Yankees near Fleetwood Hill, the Confederate cavalry commander told artillery officer Captain Hart to investigate. Hart had not gone far when a second messenger from McClellan arrived and told Stuart, “General, the Yankees are at Brandy.” Stuart quickly ordered the 12th Virginia, 35th Virginia, and a section of horse artillery toward Brandy Station. Stuart quickly followed and soon ordered Jones and Hampton to ride to face the new enemy threat. Rooney Lee’s men and the dismounted skirmishers were left at St. James Church to deal with Buford.

The second section of Martin’s battery was brought up to add firepower to the other section, which was down to one gun as its second was disabled due to a stuck round in the bore, and support Wyndham as he was finally ordered to advance on the key high ground. Wyndham, riding with the 1st New Jersey Cavalry, led his brigade forward. With drawn sabers and a wild shout, the bluecoats dashed across the railroad tracks and thundered over the field toward Fleetwood Hill.

McClellan, who was watching the Yankees, knew help was needed now. Turning to the east, he spotted the 12th Virginia Cavalry, under Colonel Asher Harman, riding to his aid. McClellan quickly swung into the saddle and galloped toward the horse soldiers, urging them to hurry. With his gun out of ammunition, Carter was withdrawing from the advancing bluecoats, who were 50 yards from the crest of the hill, when Harman and his men arrived.

The 12th Virginia slammed into the 1st New Jersey. In the swirling, choking dust, gray-, butternut-, and blue-clad horse soldiers blazed away with revolvers and slashed with sabers. The 12th Virginia was driven off, as was the 35th Virginia when it entered the fray.

“The heights of Brandy and the spot where our headquarters had been were perfectly swarming with Yankees, while the men of one of our brigades were scattered wide over the plateau, chased in all directions by their enemies,” recalled Major Heros von Borcke, a Prussian serving as Stuart’s aide.

As the Rebel cavalry rallied for another charge, elements of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry joined the New Jersey horse soldiers. Then the Confederates charged again, this time with the 6th Virginia, which had just arrived after being sent by Hampton (the 6th Virginia was part of Jones’s brigade but was fighting with Hampton back at St. James Church). The New Jersey cavalrymen found themselves in a bad way as they were nearly surrounded in a sea of gray and butternut. To break free they desperately charged two Confederate batteries that had arrived on the scene. The Rebel gunners put up a determined stand as one artillerymen shouted, “Boys, let’s die over the guns!”

Fighting grew in intensity as the 1st New Jersey attempted to break out of the Rebel cavalry and guns. Three times their guidon was captured, and three times it was recaptured, the last time by a small band from the 1st Pennsylvania, which was fighting to the left of the 1st New Jersey. When the 1st New Jersey finally limped away exhausted, its commander, Lt. Col. Vigil Brodrick, lay dead, while Wyndham had a bullet in his leg.

Martin’s battery, meanwhile, moved its guns to the southwest side of the bottom of the hill and opened up on the Confederates. The Federals soon had unwelcomed visitors with the 6th Virginia charging toward them. The New Yorkers blasted away with canister, but the Rebels kept coming and overran them. The Federal gunners fought desperately with revolvers and rammers, but it was not until the arrival of some Union cavalry that the Virginians retreated back up the hill.

As the fighting raged on and around Fleetwood Hill, Martin and his surviving artillerymen again fired into the Southern horsemen. This time the 35th Virginia overran the guns and attempted to turn them on the Yankees, but the arrival of two companies of the 1st Maryland Cavalry changed their minds. The Virginians retreated. So did Martin, whose three guns were useless now as one had a burst barrel and the other two were spiked or wedged. With his artillery horses dead and only six men out of 36 unharmed, Martin abandoned his guns.

Two Rebel batteries arrived on Fleetwood Hill, quickly unlimbered, and hammered away at the Yankees. Gregg soon ordered Colonel Judson Kilpatrick to attack with his fresh 1st Brigade. A lieutenant in the 10th New York Cavalry, which was charging on the right, recalled meeting a large body of Rebels: “The Rebel line that swept down upon us came in splendid order, and when the two lines were about to close in, they opened a rapid fire upon us. What then followed were indescribable clashing and slashing, banging and yelling.”

Wade Hampton arrived, and it was Cobb’s Legion of Georgia Cavalry from his brigade that hit the New Yorkers hard, causing them to retreat off the hill. The 1st South Carolina Cavalry of Hampton’s brigade flanked the 2nd New York Cavalry, which fought briefly before fleeing as well. The South Carolinians were in hot pursuit, hacking down any stragglers.

Seeing two of his regiments falling back, Kilpatrick led the 1st Maine Cavalry into action. The 1st Maine ferociously slammed into the 6th Virginia with sabers hacking and slashing. In the brutal fighting, Kilpatrick killed a Rebel officer he knew from West Point and disliked. Despite the success of the 1st Maine’s charge, it was only temporary. Hampton’s Jeff Davis Legion attacking east of the railroad tracks and other Confederates attacking west of it forced Gregg’s men to retreat. Hampton soon called off the attack when Stuart held back cavalrymen to secure the heights. The 11th Virginia briefly followed Gregg’s retreating division, which had been joined by Duffie’s much needed troops, who had arrived too late to help. The fight for Fleetwood Hill was over.

While Gregg had his hands full at Fleetwood Hill, Buford began to press Rooney Lee, although he had been ordered by Pleasonton to remain on the defensive. “Do you see those people down there? They’ve got to be driven out,” Buford told some officers from the 2nd Massachusetts and 3rd Wisconsin Regiments in Ames’s brigade. The infantry officers could see Lee’s sharpshooters and some dismounted horse soldiers from the 10th Virginia Cavalry and 2nd North Carolina Cavalry well positioned behind a stone wall and thought they doubled their own numbers. An officer said as much to Buford, who replied “Well, I didn’t order you, mind; but if you can flank them, go in, and drive them off.”

Several companies of infantry supported by 10 sharpshooters eased their way toward the Rebels’ northern flank, using whatever cover they could find, and managed to get close to the enemy and fired into them unexpectedly. Lee’s brigade poured lead into the Federals, who scrambled back to safety.

Buford now ordered in his battered 6th Pennsylvania and the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. Enduring Confederate rifle and artillery fire, the Pennsylvanians did well until slammed into by the 9th Virginia Cavalry. In the wild melee that unfolded, the 6th Pennsylvania was shoved back until the 2nd U.S., led by Captain Wesley Merritt, entered the fight, driving into the flank of the Virginians and chasing them back over Yew Ridge, west of the stone wall. Then Rooney Lee counterattacked with the 2nd North Carolina, 13th Virginia, and 10th Virginia, shoving the Yankees off the ridge and back to their own lines.

In the confusion, Merritt and an aide approached a knot of Confederate officers and told the leading officer he was his prisoner. The officer was Rooney Lee, who took a swing with his saber at young Merritt’s head. Merritt managed to parry most of the blow, although he lost his hat and suffered a slight wound. Both Merritt and his aide managed to escape a volley of pistol shots as they galloped to safety. Rooney Lee would not be as lucky; he was wounded in the leg in the fighting around Yew Ridge.

In the end, the Federals were forced to fall back as Confederate reinforcements under Colonel Munford finally arrived. The biggest cavalry fight in North America had ended. With reports of Confederate infantry arriving to support Stuart, Pleasonton ordered Buford to withdraw around 5 pm. Conducting a fighting withdrawal, Buford took his command back across Beverly Ford with no trouble as the Confederates did not pursue.

It had been a bloody day for the cavalry of both sides as the Federals suffered almost 900 killed, wounded, and captured; the Confederates had roughly 600 casualties. Although the battle was a Confederate victory as the Federal cavalry had failed in its objective of dispersing Stuart’s forces and retreated from the field, the bluecoats had done well.

McClellan, Stuart’s staff officer on Fleetwood Hill, would later write that the battle had “made the Federal cavalry.” He continued, “Up to that time confessedly inferior to the Southern horsemen, they gained on this day that confidence in themselves and in their commanders which enabled them to contest so fiercely the subsequent battlefields.”

First cavalry battle in which Union forces held their own. Southern cavalry entered the war in better form because of the extensive experience of Southerners with horses on farms and plantations. Later, the Union forces under Sheridan became better trained and organized. The result was the foray into the Shenandoah Valley in support of Sherman’s march to the sea.