By Don Holloway

Just a few days after Britain and Germany declared war in August 1914, their territories in East Africa declared peace. Colonial relations had always been civil; no less than Queen Victoria herself had agreed to a zigzag in the border, putting Mount Kilimanjaro on the German side because her nephew, Kaiser Wilhelm II, had no snow-capped peaks in his domains. Heinrich Schnee, governor of German East Africa (modern Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania, together larger than Germany and France combined) accepted a cordial offer from British East Africa (modern Kenya) to abstain from what was sure to be a brief, distant, European spat. However, his military commander, Lt. Col. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, disagreed: “I knew that the fate of the colonies, as of all German possessions, would be decided on the battlefields of Europe [but] could we, with our small forces prevent considerable numbers of the enemy from intervening?”

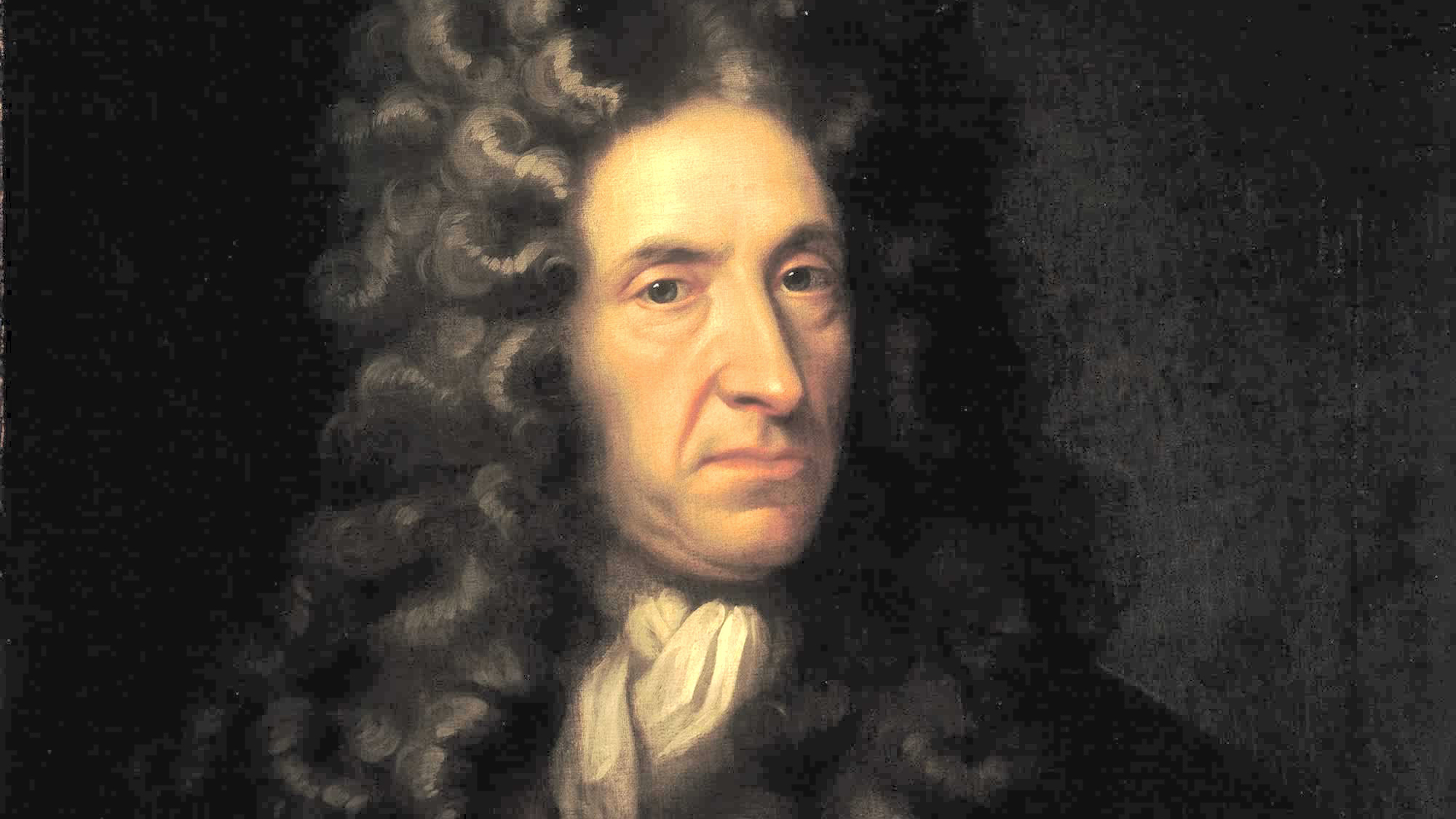

Baroness Karen von Blixen, Danish author of Out of Africa, had met Lettow-Vorbeck before the war and preferred him to the stodgy British. “He belonged to the olden days,” she remembered. “I have never met another German who has given me so strong an impression of what Imperial Germany was and stood for.” But he also was ahead of his colonial era times. In China, as part of the international coalition putting down the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, he had recognized both the effectiveness of native guerrilla tactics and “the clumsiness with which English troops were moved and led in battle.” Being wounded in German West Africa (Namibia) and serving in Cameroon taught him the best soldiers to fight a European war on the Dark Continent were askaris—native Africans under European command. But his Schutztruppe (“protective troops,” native infantry) numbered only 2,500, with a like number of native police and a handful of German officers, including Captain Karl-Ernst Göring, elder brother of future Nazi Field Marshal Hermann Göring.

Armed mostly with obsolete single-shot, black-powder rifles, with little hope of reinforcement or resupply from home and against orders, as Schnee feared a native uprising more than British invasion, Lettow-Vorbeck set about picking a fight he could not win. He sent a detachment to capture Taveta, a small village on the British side of Kilimanjaro and telegraphed Schnee in Dar-es-Salaam: “The German flag flies on British territory.”

It was an unbearable affront to English pride. The Royal Navy sent the cruiser HMS Fox to politely inform the commissioner of Tanga, the coastal terminus of the Germans’ northern railway, that the truce was off. With more than 50 hours advance notice, Lettow-Vorbeck’s askaris enjoyed a novel train ride from Kilimanjaro to Tanga. At 3 am on November 3, he and two officers bicycled by moonlight through the deserted streets to personally observe British amphibious operations. Some 8,000 Indian sepoys—Baluchis, Gurkhas, and Punjabis—were massing in the rubber, coconut, and sisal plantations on the Tanga peninsula (including a sentry who hailed, but neglected to shoot, Lettow-Vorbeck). The Germans were outnumbered eight to one, just as their commander planned.

The Allies attacked at dawn. On first receiving fire, the askaris fell back. “But when we Europeans got in front of them and laughed at them,” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck, “they quickly recovered themselves.” His machine guns tore away the sepoys’ left flank, and the Schutztruppe turned it, cutting off their advance. The drone of bullets soon was replaced by a more ominous hum. The heavy fire had stirred up beehives hung in the plantation trees—African killer bees, which drove the invaders back into the sea. Tanga is often called “The Battle of the Bees.” The British always insisted the Germans planned it that way, but “at the decisive moment all of the machine guns of one of our companies were put out of action by these same ‘trained bees,’” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck.

The British left behind three companies’ worth of new Enfield multiple-shot rifles, 16 machine guns, and 600,000 rounds of smokeless powder ammunition. Tanga was not only a British disaster; it set a precendent. From then on, most of the Schutztruppe’s gear would be supplied by the enemy.

In January 1915, the Germans crossed the border again, taking the British coastal base at Yasini, but at a cost of 200,000 rounds and six officers dead, a sizable portion of their staff. The lesson was not lost on Lettow-Vorbeck. “The need to strike great blows only exceptionally, and to restrain myself to guerrilla warfare was evidently imperative,” he said.

Throughout 1915, Lettow-Vorbeck targeted the Uganda railway. In one two-month period his raiders derailed 30 trains and blew up 10 bridges. The British put up with him while they subdued German Southwest Africa and the raider SMS Königsberg, trapped in the Rufiji river delta. Lettow-Vorbeck simply commandeered the cruiser’s crew as extra infantry and had its 105mm guns, of which there were 10, mounted on wheeled carriages as field artillery. One of the guns, which the troops manhandled over some of the world’s roughest terrain, would last the entire campaign.

But Lettow-Vorbeck could not match enemy manpower. By early 1916, the Allies assembled more than 27,000 men from Nigeria, the Gold Coast, South Africa, and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and Belgians from the Congo under a new commander. Afrikaner Lt. Gen. Jan Smuts’s commandos had fought the British to a standstill in the Boer War. Having switched sides politically and tactically, he knew, “Merely to follow the enemy in his very mobile retreat might prove an endless game.” In March Smuts launched a two-pronged attack past Taveta and Kilimanjaro, aiming to corner Lettow-Vorbeck in a kind of drive, a grand safari, a hunt for the biggest, most elusive, most dangerous game of all.

Instead of being driven, Lettow-Vorbeck led his hunters into one ambush after another over ground of his choosing and already stripped bare by his men, destroying bridges and rail lines behind him. Biding his time, he let the enemy battle mostly against his one real ally: Africa itself.

In the first year and a half of war, some 30 British fell to lions, rhinoceros, and crocodiles; one colonel said it was like fighting in a zoo. Communication wires were cut not only by enemy action, but also by giraffe and elephants blundering into them. A battle was disrupted when an enraged rhinoceros scattered first the British, then the Germans, and then the Masai tribesmen who had gathered to watch the fun. Any askari too badly wounded to go on had to be left behind. The wounded were captured if lucky; if not, they were killed that night by lions or hyenas.

Worse were the mosquitos, ticks, fleas, chiggers, and flies bearing vicious African diseases and parasites: malaria, typhoid, dysentery, sleeping sickness, and blackwater fever (named for the victim’s blood-filled urine). The Germans, with mostly ersatz quinine referred to as “Lettow schnapps” to fight against malaria, were not immune. “I am apparently very sensitive to malaria from which I suffered a great deal,” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck. He would come down with the fever no less than 10 times during the campaign.

Twice a year came torrential, equatorial African rain. It lasted for weeks and was a phenomenon the likes of which even the South Africans had never seen. “All the hollows became rivers, all the low lying areas became lakes, the bridges disappeared, and all the roads dissolved in mud,” wrote Smuts. Trucks, cars, motorcycles, and supply wagons sank up to their axles. Wireless sets shorted out. Communication fell to foot sloggers.

In March 1916, Smuts sent General Louis Jacob “Jaap” van Deventer’s 1,200-man South African Mounted Brigade overland, through the rain, toward the road junction at Kondoa Irangi, a German food depot and wireless station. As soon as they left the airy plains and entered the jungle, tsetse flies swarmed them. Trypanosomiasis, eventually fatal to humans if untreated, is quickly fatal to equines. Mounts dying under them, van Deventer’s cavalry became infantry; only 600, drenched and sick, staggered into Kondoa Irangi. The actual infantry, following a path marked by dead horses and mules rotting in the tropical heat, did not catch up until more than a week later, when of 600 men in the 2nd Rhodesian Regiment only 50 could still fight. They found the village abandoned, partially burned, and lying under the guns of some 4,000 Germans and askaris in the surrounding hills. Even when outnumbering the enemy, Lettow-Vorbeck had no intention of defending towns, much less becoming trapped in them; it was a policy that extended even to the colony’s cities.

The British took Tanga that July and at the beginning of September captured Dar-es-Salaam. Schnee fled to join his commander in the field (and become a thorn in his side throughout the war). Lettow-Vorbeck was barely in any condition to lead. “He has lost 12 kilos in the past two weeks and is yellow with fever, but will not stop,” wrote an adjutant. “He seems to live on coffee…. I watched him coming back to camp today after twelve hours in the bush … dragging his horse behind him, both of them footsore, and I am not sure which one more resembled a skeleton. One thing is certain. The horse will not last the next 24 hours, but the Colonel will.”

On the Western Front, the Allies were dying by the thousands to take yards of French soil; in East Africa they had gained territory approximately the size of France itself, stretching their enormous manpower thin. Forced to halt, they sent the Germans a formal demand for surrender, which only encouraged Lettow-Vorbeck: “General Smuts realized that his blow had failed … he had reached the end of his resources.”

Instead, at the beginning of 1917, Smuts declared victory and went off to join the Imperial War Cabinet in London. Catching Lettow-Vorbeck (whom the Kaiser promoted to general) ultimately fell to van Deventer, who had served under Smuts in the Boer War, taken a British bullet through the throat, and spoke little English. Sharing Lettow-Vorbeck’s high opinion of askaris, he vastly increased his own native forces.

The Royal Navy captured the last of the German southern seaports, from which the Allies launched their fall offensive. Cut off from home, Lettow-Vorbeck dug in on high ground at Mahiwa, stood off their flanking attacks, and encouraged them to come straight at him. The British may have learned to use askaris, but only as they used men on the Western Front, vainly charging entrenched machine guns. “Wave after wave of fresh troops were thrown against our front,” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck, adding, “The enemy by the increasing fierceness of his frontal attack was bleeding himself to death.”

He hurled them back with 2,700 casualties, more than half the Allied troops employed, but lost 95 killed and 422 wounded. “Considering the smallness of our forces, these losses were for us very considerable, and were felt all the more seriously because they could not be replaced,” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck. He regarded Mahiwa as a “splendid victory” but knew he could not afford many more of them.

By the last half of 1917, squeezed into the sparsely populated, primitive southeastern corner of German East Africa, Lettow-Vorbeck had only six weeks of food left. Germany even attempted but failed to resupply him with Zeppelin L59. With his back to the Rovuma River, the border with Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique)—Portugal had entered the war in March 1916—he determined to take back the offensive. “The war could and must be carried on,” he wrote. “This could only be done by evacuating German East Africa and invading Portuguese East Africa.”

Leaving their sick and wounded behind, on November 25 Lettow-Vorbeck and his fittest 300 Germans, 1,700 askaris, and 3,000 bearers waded the Rovuma. About 1,000 Portuguese troops contested the crossing. In what Lettow-Vorbeck called both a “fearful melee” and “a perfect miracle,” the Schutztruppe killed all but 200, resupplying on their food and gear.

That was only the start. Beyond the river lay a land of plenty, lush plantations untouched by war, flush with supplies, poorly defended. That Christmas Lettow-Vorbeck slept in a real bed with clean sheets and mosquito netting; he and his officers enjoyed a dinner of roast pork with Portuguese wine, coffee, and cigars. One of them wrote, “Never have we fared so well during the past four years.”

No less than King George V congratulated van Deventer on rendering the former German East Africa a British protectorate. But the Boer looked sourly to Portuguese East Africa as “an equally arduous campaign … for the country is vast and communications are difficult.”

By now the Schutztruppe was used to it. Marching two hours on and a half hour off, six hours a day, they covered 100 to 150 miles per week, trailed by a procession of camp followers, prisoners, women, children, old men, ex-governor Schnee and his staff, refugees, and other hangers-on, even chickens whose crowing threatened to give them away. An order “that the crowing of cocks before 9 am was forbidden brought no relief,” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck. The askaris’ wives carried their loads on their heads and their children on their backs, bearing babies along the way. “They all liked gay colors, and after an important capture, the convoy, stretching for miles, would look like a carnival procession,” wrote their leader. The Schutztruppe had become a nomadic tribe whose home was wherever the Bwana General, Lettow-Vorbeck, laid down for the night. “It was very jolly when the whole force bivouacked in this way in the forest, in the best of spirits, and refreshed themselves for fresh exertions, fresh marching and fresh fighting,” he wrote.

But never far behind them came an even larger number of Allied askaris, all of them scouring Portuguese East Africa like a horde of driver ants. “This is a queer war,” wrote one of Lettow-Vorbeck’s scouts. “We chase the Portuguese, and the English chase us.”

In July, at Nhamacurra, two-thirds of the way down to South Africa, Lettow-Vorbeck ran off the Allied garrison, captured a supply ship at the riverbank, and took the biggest cache of booty in the entire campaign. The haul included an English doctor, medical stores, 10 machine guns, 350 rifles, more than 300 tons of food, more wine and liquor than they could swill, and so much clothing that the askaris, Lettow-Vorbeck noted, “stopped stealing, as if by command. “Everyone was allowed to let himself go, for once, after his long abstinence [but] with the best will in the world it was impossible to drink it all,” wrote Lettow-Vorbeck. They poured the rest in the river.

The Allies, fearing a German invasion of South Africa, landed on the coast to head them off. With the enemy ahead and behind, Lettow-Vorbeck simply dug in his heels, let them pass him by, and doubled back to the north. That autumn the Allies could not catch up to him, but the Spanish Flu pandemic did. Half his men began coughing blood. The sick and wounded were abandoned (among them Göring, shot in the chest and captured on September 6). British aircraft dropped propaganda leaflets encouraging the survivors to desert; as they neared home, increasing numbers of natives did. The Schutztruppe was down to less than 200 Europeans and l,500 askaris when, at the end of September, they recrossed the Rovuma, shooting eight hippos for a celebratory feast.

By this time, however, neither Germany nor its former colony was faring well. “Day after day we moved through country formerly fertile and well settled,” Lettow-Vorbeck wrote. “The time for the change of direction was now approaching and there was not a day to lose.” In mid-October he turned west, over Lake Nyasa, and crossed the border again—this time into Rhodesia. The war might be all but lost, but Germany’s commander-in-chief Africa was still on the attack. As he put it, “There is always a way out, even of an apparently hopeless position, if the leader makes up his mind to face the risks.”

With a whole new colony to invade, the Schutztruppe might have carried on the war for years, but time was running out. On November 13, having won a skirmish with the British and probing ahead on his bicycle for a campsite 100 miles inside the enemy border, Lettow-Vorbeck received a telegram from van Deventer advising him hostilities had ended two days earlier. The Imperial German flag would never again fly over Africa.

A British officer who met Lettow-Vorbeck on his surrender wrote, “Instead of the haughty Prussian one expected to meet, he turned out to be a most courteous and perfectly mannered man, his behavior throughout his captivity was a model to anyone in such a position.” To corral him required the Allies to keep some 300,000 troops from the Western Front, of which they lost 20,000 Indians and Europeans and about 60,000 natives, plus an estimated 140,000 horses and mules.

For his part, Lettow-Vorbeck never commanded more than 3,000 Europeans and 11,000 Africans; at the end he was down to 150 Europeans, fewer than 1,200 askaris, and 3,000 bearers. They had fought a war they could not win, far from home, for a Fatherland most of them had never seen, battling not so much for Germany as for their general. In March 1919, he arrived in Berlin to a hero’s welcome. “Everyone seemed to think that we had preserved some part of Germany’s soldierly traditions, had come back home unsullied, and that the Teutonic sense of loyalty peculiar to us Germans had kept its head high,” he wrote.

It might even be said that his strategy proved ultimately victorious. Over the ensuing century Britain, Belgium, Portugal, and France lost most of their African colonies to rebel movements—guerrilla fighters who learned from men like Lettow-Vorbeck how to lose battles but win wars.

Yes, he was heroic, but it was a waste of time and lives as that country’s fate was decided in France after all.