By David A. Norris

For nearly a month, 4,000 New England militia aided by the Royal Navy had surrounded the great fortress of Louisbourg, the key to French Canada. Despite its massive stone walls and its heavy artillery, Louisbourg’s defense hinged on a smaller stone fortification in its harbor. Thirty guns on the Ile de L’entrée, in what the English called the Island Battery, kept the Royal Navy out of the harbor and menaced the besieging army.

Well after midnight on May 27, 1745, the Island Battery’s commander, Charles-Joseph d’Ailleboust, paced the ramparts. It had been quiet at the beginning of the night, but now, a freshening wind lashed the surf against the rocks surrounding the little fortified island. Out of the darkness and over the noise of wind and splashing waves, D’Ailleboust was shocked to hear an English voice shouting for his comrades to give a hearty three cheers. Raising the alarm, the French commander turned out his men. Flashes from cannons and muskets in the fort revealed hundreds of enemy troops. Four hundred militiamen were betting their lives that they could bring an end to the siege of the Fortress of Louisbourg with a single stroke.

Four hundred New England militiamen came to a fortified island in Nova Scotia because of a treaty signed three decades earlier. In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht ended the War of the Spanish Succession, known in North America as Queen Anne’s War. In the treaty, France lost most of Acadia, its colony in eastern Canada (including Prince Edward Island, its settlements in Newfoundland, and the mainland part of modern-day Nova Scotia) to the British.

Britain took over Port Royal, the capital of Acadia, and changed its name to Annapolis Royal. France was allowed to keep Cape Breton Island. Today part of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, Cape Breton’s nearly 4,000 square miles were separated from the continent by the narrow Strait of Canso. The French brought in exiled colonists from Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. To protect Quebec and their other North American possessions, France started the construction of what would become the most formidable citadel in North America: the fortress of Louisbourg.

Louisbourg, on the eastern coast of Cape Breton Island, guarded the St. Lawrence Bay, protecting the entrance to the St. Lawrence River and Canada. Two small peninsulas and a scattering of little islands left an entrance into a harbor that was roughly two miles long and half a mile wide.

Built on the western side of the harbor, the town of Louisbourg was edged by two and a half miles of walls that rose as high as 36 feet in some places. An 80-foot-wide ditch surrounded the walls. Reefs and shallows partly protected the water approaches to the city, and marshy terrain made land attacks from many angles practically impossible.

Added insurance against British attacks came from two works outside the main city. The Island Battery guarded the entrance to the harbor with 30 28-pounders. On the northern side of the harbor, the 30 big guns, mostly 42-pounders, of the Royal Battery could sweep the harbor of any attackers missed by the Island Battery.

Louisbourg’s heaviest walls protected the land side to the west. To the north was the protected harbor, and to the east a wall overlooking a stretch of ocean. Bastions protected the corners and gates. To the northeast of the city was a short stretch of land leading to Point Rochefort, and a chain of rocks and shoals leading out to the Island Battery. With its walls and massive stone barracks and other government buildings, Louisbourg looked more like a fortified European city than a frontier outpost.

Although rather neglected by France, Louisbourg long represented a peril hanging over the British colonies along the Atlantic Seaboard, particularly New England. The harbor nursed privateers and French naval vessels to attack their maritime trade. From the land, French soldiers and agents pushed their Indian allies to attack English frontier settlements.

War came to the New World again in 1739, when Britain and Spain clashed in the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Friction between New France and New England flared into King George’s War in 1744. A parallel to Europe’s wider War of the Austrian Succession, the battlefront of King George’s War was the dividing line between the New World empires of Britain and France.

When the new war broke out, Louisbourg had 600 regular soldiers. About 2,000 civilians lived in or near the town, and among them were about 1,400 men serving as militia.

About one quarter of the regulars were from the Régiment de Karrer, a unit of German-speaking Swiss soldiers. Their red uniform coats made them resemble British troops.

At the best of times, life was tedious in the isolation of Louisbourg. The remote town attracted far fewer settlers than the more promising locations of the English colonies farther south on the Atlantic Seaboard. Fog often covered the town and the surrounding waters and countryside. In winter, ships avoided visiting because of storms and drift ice.

The lives of the soldiers in Louisbourg were bleak. Many of them had joined the colors only to avoid prison terms. Pay and treatment were poor. Their straw bedding was replaced once a year and the barracks were so foul that the soldiers preferred to sleep outside except in winter weather.

To supplement their income, officers were allowed to sell wine and food to their men, often at unfair prices. Some officers were more concerned with their farms or mercantile businesses than their units.

France declared war on March 15, 1744, two weeks before England got around to returning the favor. Louisbourg rated far down the list of French concerns and was notified of the declaration of war by a dispatch sent on a merchant ship.

The timing of the declarations of war gave the French a head start. The commander at Louisbourg, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Le Prévost Duquesnel, sent François Du Pont Duvivier to attack the nearest English post, a fort on the Strait of Canso. Duvivier was assigned 350 sailors and French and Swiss troops for the attack.

Canso’s main defense was a wooden blockhouse built by the fishermen who inhabited the place. The post’s 90 men were commanded by Captain Patrick Heron of Governor Richard Phillips’ Regiment (later the 40th Regiment of Foot). Before the French troops landed, two privateer vessels opened fire on the fort. With shot tearing through the walls of the blockhouse, Heron ran outside to wave a white flag. He later claimed that his best course was to surrender early to get more generous terms. Heron and his men were in Louisbourg before the English in Boston knew war had been declared.

Next, the French took aim at a more important target, Annapolis Royal. Led by Major Paul Mascarene, about 100 soldiers held the fort. Long years of neglect had left the fort’s earthen walls so eroded by rains that the post’s cattle wandered back and forth over them.

Ninety French soldiers and four officers joined by about 400 Indians surrounded Annapolis Royal. Warned that hundreds more troops were coming with two ships, the 64-gun L’Ardent and the 50-gun Caribou, the French demanded the surrender of the fort.

Mascarene refused the offer, wisely, it turned out. The French ships never joined the attack. Meanwhile, two small vessels brought 50 more men from Boston, sent by Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts. Eventually, the ineffective siege was lifted and the French returned to Louisbourg.

An anonymous French chronicler, the Habitant of Louisbourg, saw the feeble fall campaigns against Canso and Annapolis Royal as the source of disaster. “Perhaps the English would have let us alone had we not first insulted them,” he wrote, and “not taken into our heads to waken them from their security.”

The Habitant of Louisbourg may have been wrong about New England’s intentions. For years, Louisbourg was seen as the “Dunkirk of America,” a reference to the French port’s history as a haven for French privateers.

Personifying the privateer menace was Pierre Morpain, one of France’s most renowned corsairs. During Queen Anne’s War, Morpain menaced English shipping in the Caribbean and the North Atlantic. Once he captured a frigate, and in one 10-day cruise he took nine ships and sank four others. Almost 60 years old, Morpain was still around, serving as the port captain of Louisbourg Harbor.

Even before the attacks of 1744, Shirley was suspicious of Louisbourg. He had sent that small reinforcement to Annapolis Royal before he knew of the declaration of war. The governor also wasted no time in bolstering Boston’s defenses and sending troops to strengthen the garrisons in Maine. By late 1744, plans were brewing for a colonial campaign against Louisbourg.

Back at Louisbourg, the L’Ardent and Caribou left to shepherd an East Indian convoy to France. The governor died suddenly in October. His replacement was Louis Du Pont Duchambon. Born in France in 1680, Duchambon had spent a long life of service in Canada. By 1745, Duchambon suffered from health problems, and he had become cautious and indecisive as a commander.

Winter ended active military operations, but grumbling intensified among the garrison troops. It was bad enough to endure poor rations, tolerate low pay, and be cheated by one’s officers. Adding to the soldiers’ grievances was the failure to pay them some promised prize money for taking Canso.

On December 27, the town was alarmed by the garrison drummers beating a call to arms. There were no English ships on the horizon; the drummers summoned the troops to join a mutiny by the Régiment de Karrer. Nearly all the enlisted personnel in Louisbourg joined the mutiny and took their officers hostage. Duchambon capitulated and placated the men. The troops went back to their duties, but the officers were never sure of their loyalty again.

At the beginning of 1745, Shirley called a secret session of the General Court of Massachusetts, the colony’s administrative and legislative body. At the session, the governor unveiled a plan for sending ships and troops to attack Louisbourg.

The court at first balked at the ambitious and expensive plan. Shirley worked behind the scenes, pointing out that New Englanders would get the supply contracts and officers’ commissions. Good news came from Captain Heron and the other Canso prisoners, who returned after the French paroled them. They brought reports that the Louisbourg garrison was mutinous and their food and supplies were running short.

On January 24, 1745, the General Court granted Shirley permission to press on with the attack. Its war motion passed by a single vote; tradition holds that it was only because one delegate who opposed the campaign broke his leg on the way to the session.

Time was of the essence. England, embroiled in Europe, would provide little help for this colonial sideshow. A French fleet was expected to reinforce Louisbourg in the late spring, so the expedition was readied with great speed. New England united to provide troops, supplies, and ships for the campaign, but other colonies were not as threatened by Louisbourg and held back. New York sent some cannons, and Pennsylvania agreed only to contribute some supplies. From Philadelphia, a skeptical Benjamin Franklin wrote his brother in Boston, “Fortified towns are hard nuts to crack, and your teeth have not been accustomed to it…. Some seem to think that forts are as easy taken as snuff.”

Shirley also sent a request to Captain Peter Warren of the Royal Navy, who was then in Antigua, to send some ships to join the expedition. Warren was well acquainted with the region. He spent most of his naval career in the Caribbean or North America, and his wife was a Bostonian. When Warren received the request, though, he felt bound to use his ships to defend the West Indies and reluctantly refused.

Shirley chose William Pepperrell, a prominent merchant from Kittery, Maine, to command the expedition. Born in Kittery in 1696, he was the son of a Welsh-born shipbuilding and fishing fleet owner also named William Pepperrell. From humble circumstances, their family attained great wealth dealing in fish, land, and the mercantile trade. Pepperrell was well liked and widely respected in New England. He had served as a militia officer for years, and his career in trade made him well acquainted with his region’s people, the frontier, and the sea. For the expedition, he was commissioned a lieutenant general three times over by the colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire.

Pepperell led the largest military expedition so far raised by the British colonies. Not a single British redcoat sailed with him; every man was a colonist. There were approximately 3,000 soldiers from Massachusetts, 500 from Connecticut, 350 from New Hampshire, and a smaller number of Rhode Islanders.

In some eyes, the expedition took on aspects of a crusade. Vehemently Protestant New Englanders saw French-inspired Indian raids as a religious war sparked by Catholic missionaries in Canada. A chaplain for the expedition, Reverend Samuel Moody, announced he was bringing a hatchet to smash the images in the church of Louisbourg.

Most of the force sailed from Boston on March 24. First, the ships would rendezvous near Canso and retake the fort before moving on to Louisbourg. About 90 colonial vessels, mainly schooners, sloops, and fishing smacks, were assembled to carry the troops. Guarding them was a flotilla of armed New England ships. Heading them was the 20-gun frigate Massachusetts, under Captain Edward Tyng. The Caesar and the Shirley Galley also carried 20 guns. The Prince of Orange and the Boston Packet mounted 16 guns each. Also from Massachusetts were three smaller armed sloops. Three armed vessels came from Rhode Island, one from the colony’s government and two hired by Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire each sent one armed sloop.

A storm of rain and snow scattered the colonial ships. Sixty-eight vessels pushed through to gather off Canso on April 5. The rest straggled in over the next few days.

Canso was quickly recaptured and fortified, but Louisbourg was safe for the moment. Ships sent to look in on the fortress found the eastern coast of Cape Breton blocked by drift ice. Aboard one of the vessels on April 15, the Reverend Joseph Emerson wrote that the ship was “all day encamped with vast cakes of ice some are judged to be 50 feet thick.” The colonial ships stayed out, taking a few prizes bound for the enemy port. The ice was in a way lucky for Pepperrell, as it provided a three-week delay to allow time to drill his untrained army.

Connecticut’s troops left New London on April 14, accompanied by the 12-gun Connecticut sloop Defence and the 14-gun Tartar from Rhode Island. Off Nova Scotia on April 3, they were spotted by the Renommée, a 36-gun frigate bound from France with supplies for Louisbourg.

Captain Daniel Fones steered the Tartar away from the fleet and toward the intruder. Fones fired his bow chasers and then turned away, provoking the frigate into a chase. French shots severed the Rhode Islanders’ jib halyards, but Fones pushed his little ship for hours, leading the frigate away from the fleet.

The Connecticut vessels reached Canso on April 24 with the news that Fones had sacrificed his ship to save them. At 1 pm the following day, a ship approached and fired five guns in a triumphant flourish. It was Fones and the Tartar. The Rhode Islanders had escaped from the French frigate in the darkness two nights earlier.

On April 22, diverted from convoy duty by Warren’s orders, the British frigate Eltham reached Canso. Warren arrived the next day. With new orders from London, the naval commander gambled that he could leave the Caribbean colonies and join Pepperrell. With Warren were the ship of the line Superbe and the frigates Mermaid and Launceton.

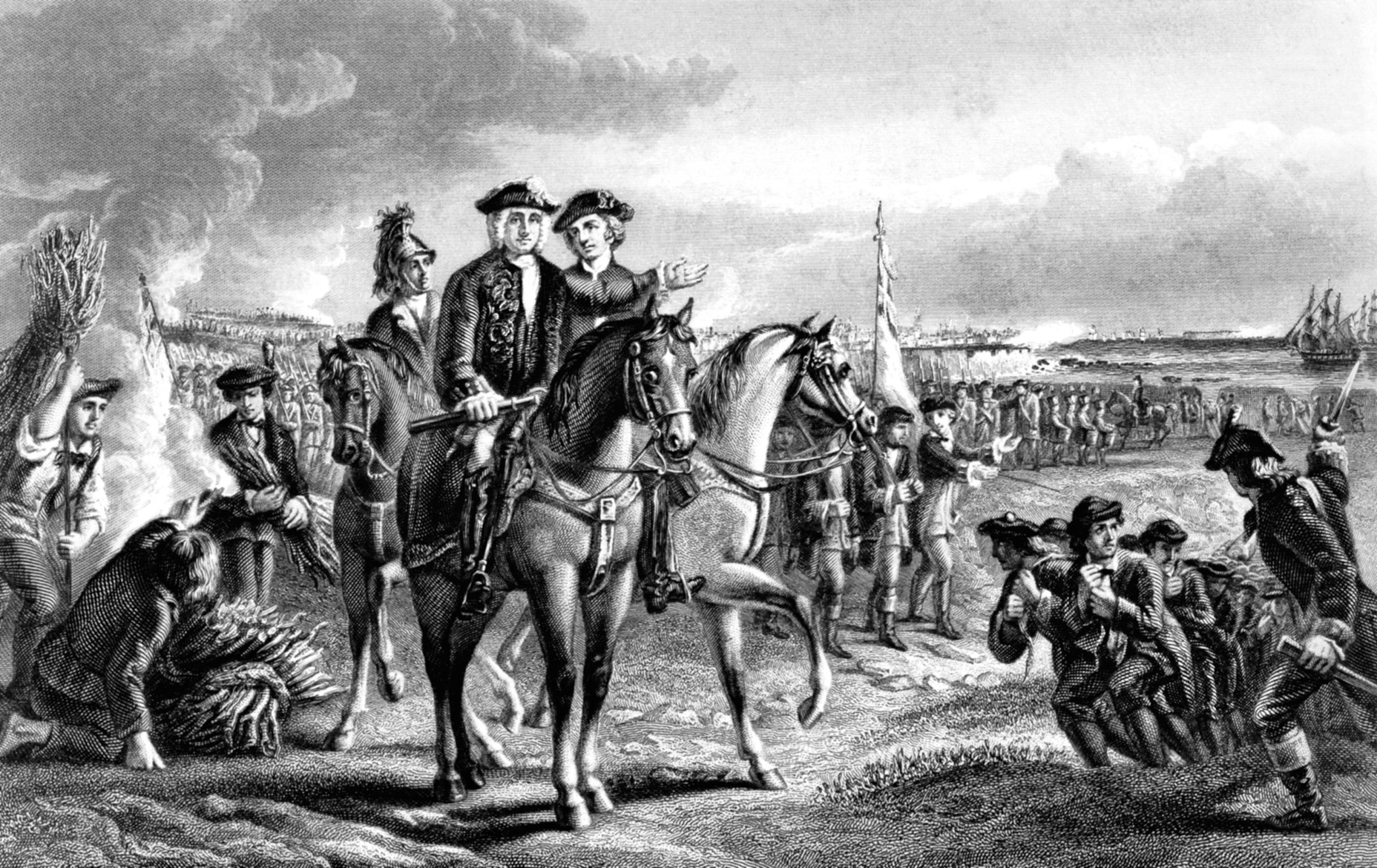

Pairing Warren as sea commander with Pepperrell as the army leader was a stroke of luck. The two were old friends, and Warren had spent considerable time visiting Pepperrell’s home in Maine. One thing they shared in common was the idea of putting the British flag over Louisbourg. Back in 1743, Warren recommended such an attack to the British Admiralty. He believed that taking Cape Breton Island and Louisbourg would “be of greater consequence to Great Britain than any other conquest that we may hope to make in a Spanish or French war.”

When the ice thinned out, the New Englanders left two companies to guard Canso and moved on to Louisbourg. They reached their destination about 8 am on April 30 and dropped anchor at a sheltered spot on Gabarus Bay about two and a half miles west of the enemy citadel.

No scouts or messengers had reported the attack on Canso, so Duchambon and the garrison were completely surprised. The city’s bells tolled, and guns boomed from the walls to summon the militia from the nearby countryside.

Louisbourg, although formidable in appearance and construction, had dangerous weaknesses. The walls had 148 emplacements for cannons, but many were empty. Perhaps there were as many as 90 big guns on the fortress walls, not counting those in the Royal Battery or Island Battery. The fortress was well situated to repel attack from the sea but was vulnerable to heavy artillery if siege guns were planted on higher ground overlooking the city.

Although the French commander was unwilling to risk sending out his troops, bolder officers pushed for action. Antoine La Poupet de La Boularderie was a former army officer who retired to an inherited estate in Cape Breton. Hearing of the invasion, he traveled in an open boat to the fortress. At Louisbourg, he insisted that Duchambon launch an immediate counterattack. If half the garrison, he thought, fell upon the New Englanders while they were fatigued and disorganized from their landing, the affair could be ended quickly. Morpain, the old privateer, backed the plan for action.

Duchambon finally allowed de La Boularderie and Morpain to lead an attack on the landing party. Too cautious to risk a substantial portion of the garrison, he allotted only 24 soldiers and 50 civilian volunteers. Advancing past the walls, Morpain and de La Boularderie realized that they had underestimated their peril. Hundreds of men were already landed. Confident and well organized, the English colonists turned their muskets on the small French detachment. Once the transports and naval vessels saw the French were attacking, they bombarded them with their cannons.

The French could do nothing but retreat. Left behind was de La Boularderie, who was wounded and captured. Morpain was also wounded and stranded on the field, but one of his slaves rescued him and helped him back into Louisbourg. French losses were only about 16 killed or wounded, but the skirmish was costly in removing two of Duchambon’s most decisive and skilled officers. By nightfall, 2,000 of Pepperrell’s men were ashore. The rest of the men were landed on May 1.

On the evening of May 2, 400 men marched from camp. They explored the terrain around the fortress and torched some French warehouses filled with naval stores. Winds blew the heavy smoke over the Royal Battery.

Within the walls of the battery, the officers feared a disaster. Much of the rear wall had been torn down for repairs. Now, as smoke from the burning warehouses engulfed the battery, it appeared that they were under a heavy attack. After a hurried plea to Duchambon, the fortress commander granted permission to spike the guns and withdraw to the city.

The gunners departed so quickly that they left their flag flying. The next morning, Colonel William Vaughan and a small reconnaissance party came within sight of the Royal Battery. From above, the outline of the battery was like a chevron, pointing down toward the harbor. Embrasures for the guns pierced the tops of the stone walls, rather like the battlements of a castle. Round turrets at either end flanked the walls. Vaughan noticed that beneath the waving flag no smoke rose from the chimneys of the suspiciously silent fortifications. One of Vaughan’s Indian scouts crept up to the walls and found the works utterly deserted.

Vaughan’s party entered the fort. Eighteen-year-old William Tufts climbed up the flagpole holding his red coat in his teeth. Tufts tied his coat to the top of the pole as a substitute flag. Vaughan sent a messenger to Pepperrell asking for reinforcements. Before more men could arrive, several boats of French troops approached to take back the fort. The New Englanders opened fire, pelting the boats with musket balls fiercely enough that the French turned back for Louisbourg.

Brigadier General Samuel Waldo was placed in charge of the captured Royal Battery. Tufts’ coat no longer flew over the fort. “Pray favour us with one of the union flags,” he wrote to Pepperrell on May 3. “We make a mean appearance under two old fishermen’s ensigns.”

Had the French broken the trunnions of the abandoned guns or even burned the carriages, the battery would have been of little use to its captors. As it was, nothing had been done other than spiking the pieces. Major Seth Pomeroy, a gunsmith, supervised 20 men who drilled out the vents. One by one, the pieces were ready to turn against the walls of the citadel.

Brought with the expedition were 34 guns: 8 22-pounders; 10 18-pounders from New York; 12 9-pounders, and four coehorn mortars (sometimes called “Cowhorns” by the colonists). Also packed was a quantity of 42-pounder ammunition in anticipation of putting captured French guns to use.

Two miles of mostly marshy ground separated the landing point and Green Hill, a piece of high ground where siege batteries were to be planted to bombard the fortress. The first gun transported into the marsh sank to its hubs and then disappeared into the mud. Horses and oxen could not work in the soft, wet ground. Many of the soldiers were used to handling sledges to transport timber and masts. Several new sledges were built to carry the guns. Teams of 200 pulled the sledges with ropes all the way to Green Hill. By May 5, the first guns were ready to open fire.

The contrast between Pepperrell’s amateur soldiers and European regulars could hardly have been sharper. In general, they carried out their siege in a disorganized manner. When the men were off duty and away from the trenches, they spent their time in a number of recreational pastimes such as wrestling, pitching quoits, or target practice.

Waldo was hounded by his men to get them more rum. Soldiers on the expedition were entitled to one gill and a half (six ounces) of spirits per day, but supplies at the battery often ran out. “We are in great want of good gunners who have a disposition to be sober in the daytime,” wrote Waldo. He said most of his men were less focused on their duties than “speculation on the surrounding hills” and “ravaging the country.”

Pepperrill’s expedition often ran short of necessities. Waldo worried that each firing of the 42-pounders in the Royal Battery burned 16 pounds of gunpowder. Bombardment often ceased for want of more powder. Fortunately, Warren had some powder to spare aboard his ships and shared it.

Solid shot, at least, was easily obtained. With the incentive of small cash bounties, men chased rolling shot from the enemy’s guns and turned the projectiles in to be fired back at the enemy’s walls.

Deadlier than the artillery of Louisbourg were the colonists’ own siege guns. Few men in the expedition were experienced gunners. Improperly loaded or too heavily charged, several of their guns exploded. When a large gun was split, as the colonials referred to the bursting of a gun, it was often fatal to one or more gunners. Warren helped once again, assigning some naval gunners to tutor the landsmen.

The expedition commanders knew little of siege craft, and planning new batteries was done in an inefficient and often dangerous way. Sappers approached new works in trenches that ran straight and open to French fire rather than in a safer zigzag pattern.

Even if fired by amateurs, the growing number of guns that lobbed shot and bombs took a toll on the city. The first shot to land in Louisbourg killed 14 people. Houses were smashed, and the walls, bastions, and gates were steadily chipped away. Women and children sheltered in fort casemates. “Some long pieces of wood had been placed in the casemates in a slanting position and this so deadened the force of the bombs and turned them aside that their momentum had no effect,” according to the Habitant of Louisbourg.

Warren’s ships and the civilian privateers snapped up several small French vessels that tried to enter the harbor. The frigate Renommée never made it past the blockade and eventually returned to France without delivering dispatches or supplies for Louisbourg.

On May 19, 1745, Captain Alexandre de La Maisonfort Du Boisdecourt neared the fortress in the 64-gun ship of the line Vigilant. The ship was packed with enough gunpowder, ammunition, and food to supply the garrison until the arrival of more aid from France. Favorable winds beckoned for the last few miles to the harbor entrance, but La Maisonfort hesitated when he saw artillery fire ashore. Then, he was stunned when two smaller ships fired on him.

Some accounts state that Royal Navy frigate Mermaid opened fire on the ship of the line, and others credit Captain John Rous and the Shirley Gallery. Most likely, both ships took a hand in confronting the Vigilant. In any event, Maisonfort abandoned his course for the harbor entrance and turned his attention to the smaller ships.

Rous kept ahead of the Vigilant and steered toward a fog bank. Then the wind dissipated the fog, revealing Rous’s objective, the rest of Warren’s warships. The Vigilant wheeled about with several vessels in pursuit. By 5 pm, two English frigates were close enough to open fire on the French vessel. One of the frigates lost its mainmast and much of its rigging but the fighting delayed La Maisonfort until more British ships sailed within range. Along with the Royal Navy, the little Shirley Galley kept up a stubborn fire; La Maisonfort later noted that Rous’s ship killed seven of his men and “broke all his glass and china ware.”

After taking considerable damage and 80 casualties, the Vigilant struck its flag. “There was not one of us,” wrote a disgusted Frenchman who watched the disaster unfold from the shore, “who did not utter maledictions upon what was so badly planned and so imprudent.”

About 100 small cannons, stores for the garrison, and supplies for two French warships under construction in Canada were on board the captured ship. Pepperrell’s officers, concerned about their dwindling supply of gunpowder, saw their problem eased by the capture of the munitions.

The capture of the Vigilant was only part of a remarkable run of English good luck. Although the weather was often foggy, temperatures were mild and there was little rain. The enemy sent little opposition against the landing on April 30, and in a panic abandoned one of its most important works, the Royal Battery. Even little turns of luck were noted. Sappers digging a trench uncovered a rock large enough to halt their progress. Just after the frustrated soldiers left the blocked trench, the rock was removed when a French shot plunged down onto it.

Even with extra helpings of good fortune, though, the siege became bogged down. By late May, between the sick lists and detailing some soldiers to man the captured Vigilant, Pepperrell had only 2,100 men fit for duty. As much as the colonists fired into the fortress, the French garrison managed to repair the damage to the walls. Looming over the campaign was the prospect of a fleet arriving from France with reinforcements and saving Louisbourg.

Duchambon still had one vital asset. As long as the French held the Island Battery, they could keep the British ships out of the harbor and harass the colonial artillery positions on land. The Island Battery, like the Royal Battery, resembled a little castle. The island was oriented diagonally from northwest to southeast, with its long northern face and the eastern edge protected by a battlemented stone wall. Guns pointing from the embrasures covered the harbor entrance. To the west and south, the island was protected by rocks jutting from the low island and the surrounding waters as well as coverage from the guns of Louisbourg.

Three assaults on the island were postponed for lack of volunteers or from the objections of officers who doubted it could be done. To stimulate volunteering for the mission, soldiers were promised a share of prize money if the battery was taken. For an assault planned for the night of May 23, a total of 200 volunteers showed up. They were a scattering of unorganized men from different units, without officers, and many of them were drunk. As if a bright moon was not enough to light the harbor and reveal a nighttime boat attack to the French, a display of the Northern Lights flashed overhead. Between the unfit state of the men and the unnaturally bright night, this attack was also called off.

Volunteers gathered for another try against the Island Battery on the night of May 26. Allowed to choose their commanders, the men voted in a fellow named Brooks as their temporary captain.

Brooks’s men left the shore in front of the Royal Battery and steered their whaleboats into Louisbourg Harbor. On their way to the battery, they were joined by a detachment that left from Windmill Point. The force numbered about 400 men. Rather than rowing with oars, they used paddles, which were quieter.

If the stone ramparts of the Island Battery were dark and silent, the sea was not. When they launched their boats around midnight, the waters were calm. But winds picked up quickly and sharply. Later, veterans of the raid agreed that they fought the most violent surf and waves they had seen since the expedition landed in Gabarus Bay. Churning waves overturned boat after boat before the men could reach their objective.

Nearing the island, the soldiers found that the only place to land was a narrow beach bracketed by dark rocks splashed with waves and foam. Only three boats at a time could unload. From the boats, men stepped ashore dripping wet, and many of them found their ammunition was soaked and useless.

D’Ailleboust, the battery commander, was awake and outside on watch. Under his command were about 60 soldiers and 140 local militiamen. Brooks’s men continued trudging ashore with their scaling ladders. All was well until about one third of the men were out of the boats. Then one man, overcome with eagerness or rum, decided to shout a hearty three cheers.

Alerted to the attack, the Island Battery’s garrison turned out to repel the raiders. Besides their 28-pounders, D’Ailleboust’s men had several swivel guns and numerous muskets to put into action. By the light of their muzzle flashes, the French garrison saw the enemy militia and their boats as they poured cannonballs, grapeshot, and profanity into them. Some of Brooks’s men fired their muskets, mostly in vain, against the French sheltering behind their stone ramparts. Other colonists leaned their scaling ladders against the walls and tried to climb into the battery. Brooks, by one account, was hauling down a French flag when a Swiss soldier killed him with a cutlass.

Few of the raiders made it back that night. The men still aboard boats turned them around and headed for safety. French fire smashed and splintered the whaleboats hauled up on the beach, trapping their crews on the island. Some of the stranded men fired their muskets at the French all night. A French official wrote that their fire was “extremely obstinate, but without effect, as they could not see to take aim.”

After daylight, 119 survivors surrendered to d’Ailleboust. Sixty others were dead on the island or drowned in the surrounding waters. French casualties were small; one writer recorded that only two or three of the island garrison were killed or wounded.

News of the disaster swept through Pepperrell’s camps. No one knew how many of the men trapped on the island were dead. Samuel Curwin recorded in his journal, “A hundred men are missing, and we are in hopes they are taken, as two boats laden with men were seen going into the town after the attack, when the French gave three hurrahs.”

For Pepperrell’s men, the Island Battery attack was the worst setback of the siege. D’Ailleboust won the admiration of the garrison for the first French victory in what seemed like a grueling and hopeless campaign. Months later, the captain was awarded the Cross of St. Louis by King Louis XV.

Although protected by water, the Island Battery was vulnerable to bombardment from higher ground. Lighthouse Point, about 1,000 yards across the harbor entrance from the battery, offered fine potential artillery positions to bombard the island, but getting English guns to Lighthouse Point would require dragging them three to four miles from the Royal Battery or landing them a long way from the point. Either option required pulling the guns across terrain strewn with rocks, covered with forests, or drenched with swamps.

Only a few hundred yards from the lighthouse was a little cove where the French had located ships for repairs. A valuable prize was found there: 10 heavy French guns. Removed from a ship years earlier, the guns had been abandoned and left to sink in the muck. The guns were cleaned up and dragged to the site of the proposed battery.

After repulsing a sortie made by 100 troops sent by boat from Louisbourg, the British moved more guns to join the captured French pieces. On June 11, the new Lighthouse Battery joined in a bombardment of the French works. The Island Battery was soon knocked out of action.

By this time, Pepperrell and Warren were reinforced by more ships from England. Warren now commanded more than 3,500 sailors and marines aboard six ships of the line and five frigates with a total of 554 guns.

With the Island Battery ruined and their force considerably strengthened, Pepperrell’s commanders agreed it was time for an all-out attack. However, there was another card to play first. Up to that point, the French garrison expected help to arrive, and it did not know for certain what happened to the Vigilant. La Maisonfort was asked to write a letter to be delivered under flag of truce. Ostensibly, the letter was to warn the garrison not to mistreat its prisoners and to praise the consideration given to the crew of the Vigilant. But the message really was intended to convey the news that the Vigilant was captured and no help was coming.

Hope faded for the disheartened garrison, as soldiers and townsfolk realized that they would never be relieved. Louisbourg’s prominent citizens and officers pleaded with Duchambon to surrender the city. On June 15, Duchambon asked for a parley to negotiate the capitulation. Two days later, the French flag was lowered from the most forbidding fortress in North America.

Articles of surrender were quite generous. Officers, soldiers, and inhabitants would be paroled and conveyed to France. The garrison could march out bearing arms and flying its flags. The colors and weapons would be turned over to the English but would be returned when they reached France. There was one unusual provision: “If any persons of the town or garrison did not wish to be recognized by the English, they should be permitted to go out masked.”

New England, and England itself, were elated by the victory. Warren was promoted to rear admiral, and William Pepperrell was made a baronet. But squabbles soon dulled the glow of success. New Englanders resented Warren quickly sending in his marines to hold the fortress and believed that the Royal Navy tried to take credit for their siege. While there was considerable prize money for the navy, the soldiers qualified for very little reward. Scores of men sickened and died before British regulars from Gibraltar arrived to take over the fortress in March 1746.

At the end of the war in 1748, diplomats met to draw up a peace treaty. During the war, the British colony of Madras in India fell to the French. More interested in their eastern possessions than Canada, British representatives traded Louisbourg for Madras.

In New England, pride in the taking of the Fortress of Louisbourg turned to disappointment and anger. All of their massive effort and the lives lost had been thrown away by distant officials who seemed to have reversed the hard-won victory on a whim.

In the next war, Louisbourg again had to be captured, and this time Britain sent the Royal Navy and regular troops. After retaking the city in 1758, the British kept it. French colonists were expelled, many to distant Louisiana, where they formed the foundations of the region’s Cajun culture.

Louisbourg’s walls were demolished by British troops. Although not the first time the British sent American soldiers overseas during the French and Indian Wars, Pepperrell’s expedition to Louisbourg was the first time an exclusively American army was organized for an overseas operation. The successful outcome showed the separate colonies what they might accomplish when they worked together. Duchambon’s surrender in 1745 set a precedent that inspired the 13 American colonies when they broke away from British control and moved toward independence. Thus, the story of the Siege of Louisbourg in 1745 is as much a part of colonial America’s patriotic heritage as the American Revolution itself. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments