By Flint Whitlock

The small French village of Merville (1940 population: 470), located just south of the coastal town of Franceville-Plage, had as its neighbor on its southern fringe an unwelcome German battery consisting of four concrete bunkers housing artillery pieces that pointed northwest toward Ouistreham and the mouth of the Orne River.

Since Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s visit to the battery site on March 6, 1944, Allied aerial photos revealed a frenzy of activity there, with it appearing obvious that the Germans’ construction arm, Organization Todt, was in the midst of installing four reinforced-concrete, earth-covered casemates.

The first and largest was identified by the British as “Type H611,” while the other three were smaller “Type 669” models. SHAEF intelligence officers knew that the Type H611 was almost always used to house 155mm field guns that had a range of 10 1/2 miles; Sword Beach, at Ouistreham, where the 3rd British Infantry Division was planning to come ashore on D-Day, was only slightly less than four miles from this battery.

It was therefore understandable that SHAEF believed that these powerful guns were, or soon would be, emplaced within the Merville casemates. No one at SHAEF was actually certain of the caliber of the guns because none of the aerial photographs showed them in any great detail.

But unless the guns, whatever their caliber, were knocked out, they would pose a grave danger to British troops landing at Sword—and possibly even farther west at Gold and Juno Beaches.

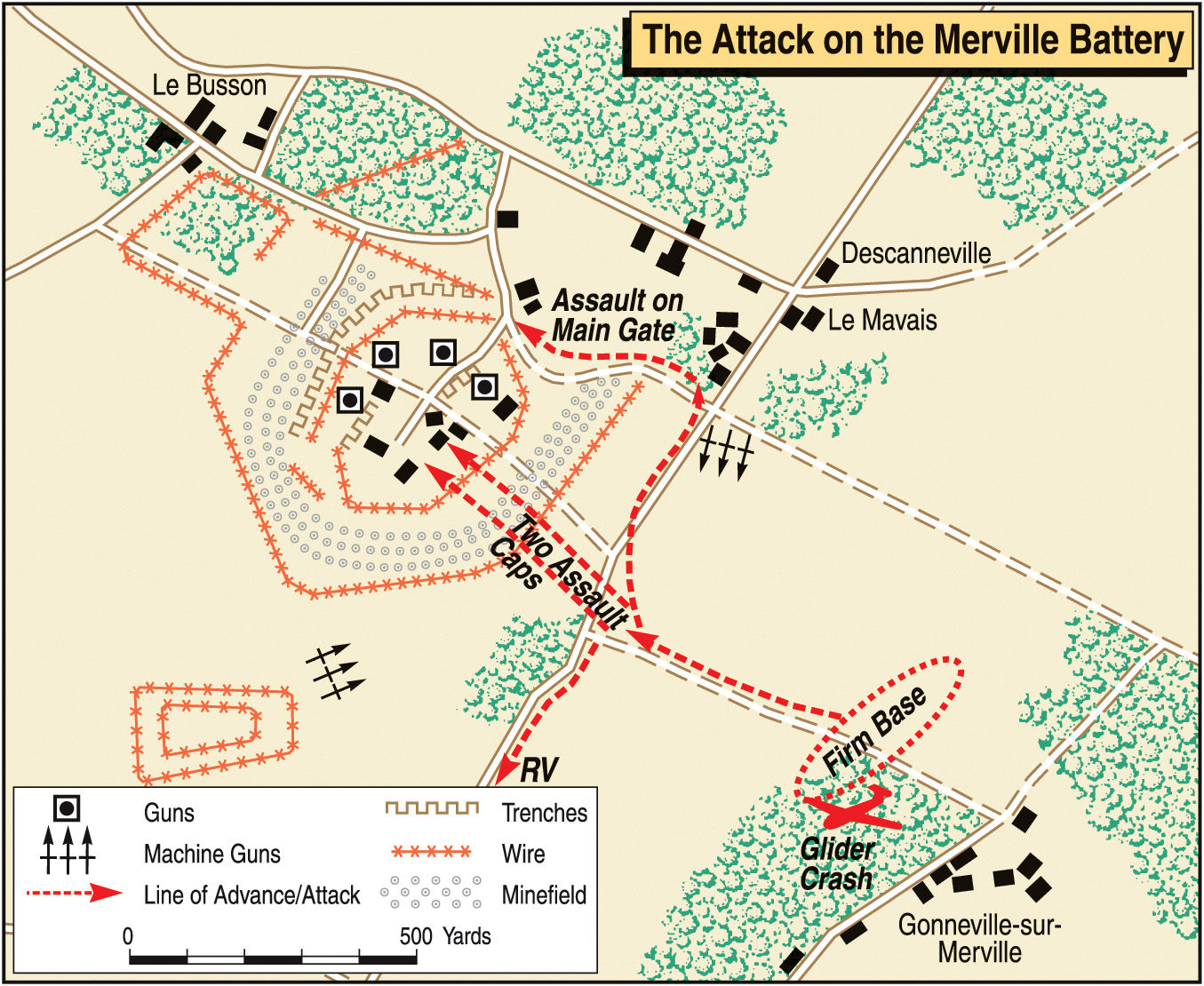

Aerial photos also revealed that encircling the battery were a 20mm anti-aircraft gun, bunkers, fighting trenches, and a partially completed anti-tank ditch. The position was also surrounded by a cattle fence enclosing a minefield of an approximate average depth of 100 yards, the inner border of which consisted of a concertina wire fence 15 feet thick and five feet high. In places this inner fence was doubled, and within it the battery position itself was intersected by cross wire.

Everyone at SHAEF was convinced that the Germans would not have poured so much concrete and so heavily defended the battery if what it housed was insignificant, and so it was added to the list of primary objectives––such as Sainte-Mère-Église, Pointe-du-Hoc, the La Fière bridge, and the two bridges over the Orne––that needed to be taken as soon as possible on D-Day. Since it was believed that the casemates of the battery were immune to aerial assault, SHAEF realized that only through a ground assault by a large number of troops could it be neutralized.

The coup-de-main assault on the two Orne bridges were the responsibility of Major John Howard’s D Company, 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire (the “Ox and Bucks”) Regiment, while the mission of taking out the Merville Battery was assigned to Lt. Col. Terence Otway and his 9th Parachute Battalion. While Howard’s planned simultaneous seizure of the Orne bridges was daring in the extreme, it was not nearly as complex and fraught with danger as Otway’s mission.

The Orne bridges and Merville Battery assaults were themselves portions of a larger plan called Operation Tonga that was designed to seal off the eastern end of the 50-mile-long invasion area. While these actions were taking place, Brigadier S. James Hill’s 3rd Parachute Brigade––made up of Lt. Col. George Bradbrooke’s 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Lt. Col. Alastair Pearson’s 8th Parachute Battalion, and Lt. Col. Terence Otway’s 9th Parachute Battalion––was given the greatest number of missions that had to be accomplished if the British, French, and Canadian seaborne forces were to enjoy a successful landing at Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

In addition, the division’s other brigade––the 5th, commanded by Brigadier Nigel Poett––had the daunting task of seizing and holding two bridges over the Orne River and Canal west of Ranville that were the only bridges in the area that the Germans could use to attack the amphibious invasion force.

Once their missions had been accomplished, the majority of the 5th Parachute Brigade would be withdrawn and held in reserve to respond to any emergencies that might arise.

Additionally, Lt. Col. Peter J. Luard’s 13th Parachute Battalion would secure Ranville, while the 591st Parachute Squadron would clear two landing strips at LZ “N,” between Ranville and Le Mesnil, for the first glider landing.

Although the objectives might seem to be more than one brigade could reasonably be expected to accomplish, Brigadier Hill said afterwards, “Looking back on my brigade’s task for D-Day, I think I would have accepted it was well-nigh impossible when 2,00 young men with an average age of 22, who, with the exception of three officers, had never seen a shot fired in anger before, were asked at the dead of night, in a foreign field, to put out of action an enemy battery and destroy five bridges interspersed with deep irrigation ditches and German wire. These tasks covered a span of seven miles.

“Thereafter, as near first light as possible, the brigade was required to capture and hold the [Le Mesnil] ridge, which was the dominating feature overlooking the Orne Valley, where the main divisional objective was the capture intact of the bridges over the River Orne and canal so that a bridgehead for a future breakout for 21 Army Group could be established. When regarded in retrospect and the cold light of day, that was a formidable task in all circumstances.

“The extraordinary thing was that no one of us doubted our ability to carry it out. During our months of training, we had built up faith in each other and faith in ourselves.”

Lt. Col. Pearson’s 8th Para was to be dropped at Drop Zone “K,” some three miles south of Ranville, from which the Royal Engineers of No. 2 Troop, 3rd Parachute Squadron, would proceed to demolish a road bridge and a railway bridge at Bures and another highway bridge at Troarn, thereby shutting off German access to the invasion area.

Otway’s battalion, which obviously had the roughest assignment (he called it a “stinker”), spent many weeks training for their role. With the four, earth-covered, concrete bunkers of the Merville battery virtually bomb-proof, Otway’s men had to figure out ways to breach the barbed wire, minefields, and machine-gun emplacements surrounding them, then get close enough to the bunkers to assault them through their firing ports, steel doors, or ventilation shafts––all within a very short period of time.

The timing for this mission was critical; the battery would have to be neutralized by 5:30 a.m. and a signal given, or else the Royal Navy would assume the raid had failed and would begin bombarding the site. At best the mission seemed suicidal, and, even though the 29-year-old battalion commander presented a bluff, hearty confidence to his men, Otway secretly doubted that any attacking force could accomplish such a mission.

Twenty-nine-year-old Lt. Col. Terence Brandram Hastings Otway (born in Cairo in 1914) did not look like the prototypical image of a leader of airborne troops. But appearances can be deceiving. As historian David Howarth observed, “At that age he commanded 750 of the toughest of British troops. He was slim and lightly built. His face was lean and gave an impression of keen intellect and an ascetic and sensitive character. One might almost have been forgiven for putting him down, at first sight, as an artist rather than a colonel of paratroops. But such appointments are more than a matter of chance.”

By D-Day Otway was, in fact, a seasoned officer with over 10 years in the army. The son of a soldier who had died after being gassed during the First World War, Otway entered the Royal Military College (Sandhurst) at age 19 and, upon receiving his commission, was posted overseas to China where, in the mid-1930s, he and his unit became the target of Japanese attacks.

His unit moved from China to India, but he was not pleased with the assignment and planned to resign his commission. On his way back to England, he learned that he had been selected for promotion to captain in the 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles. In 1939, he became the battalion adjutant, and then the Second World War broke out.

Four months before Operation Overlord, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and made commander of the 9th Parachute Battalion.

Les Daniels, a sergeant in 9th Para, said of him, “Colonel Otway was a very hard man, very stand-offish, naturally as you’d expect your commanding officer to be. No tolerance for a fool whatsoever. You daren’t make a mistake with the colonel.”

Otway’s own command philosophy was simple: “I wanted to be respected and I wanted to be considered to be a fair person, but I wouldn’t go out of my way to get popularity. I wanted an efficient, well-run, happy battalion, and I reckon I had it.”

Shortly after taking command of the battalion, Otway was informed of the invasion plan and the role that the 9th Para would play in it. “I was taken to a farm house near Amesbury, in Wiltshire, by the Brigade Major, and nothing was said. I was taken up to the first floor and there was a model, and he said, ‘You see that, that’s a battery.’ I said, ‘Yes, I can see that,’ and he said, ‘You have got to take it.’ They [the guns] were sited to fire straight along the Normandy beaches over which the British troops were due to land in Operation Overlord.”

Otway privately mulled over the awesome responsibility of leading the assault on the Merville Battery––an assignment he privately regarded as suicidal. But, ever the dutiful soldier, Otway knew he had to give it his best; the fate of the British and Canadian invasion beachheads depended on it.

While Howard’s planned seizure of the Orne bridges was daring in the extreme, it was not nearly as complex and fraught with danger as Otway’s mission. He and his men would be delivered by both parachute and glider. Any miscalculation or mis-drop on the part of the Royal Air Force, or a determined stand by the Germans, could lead to a disastrous failure—and the possible slaughter of British and Canadian troops landing by sea at Sword, Juno, and Gold Beaches. The likelihood of things going wrong was immense.

But there was nothing but to do it. The British government bought a field near Newbury in Berkshire and constructed a full-scale replica of the Merville Battery, developed from aerial photos. “If we were going to go and do this job, which was obviously very difficult,” said Otway, “we had to have a replica in this country and every man would have to know what to do. The battery was sited to fire along the length of Sword Beach, across which the British 3rd Infantry Division was going to land. Everybody emphasized to me personally what would happen if we failed––that is, the men killed on the beach.”

Otway’s 750 men spent weeks rehearsing and refining their timing and movements at the replica, often using live ammunition. Since the raid was scheduled to take place in the dark, Otway had his men constantly practicing the assault in the dead of night.

He soon realized that having his men land either by parachute or glider outside of the battery’s defenses and then fight their way in would probably not work, so he devised a plan that would have 60 men in three Horsa gliders crash-land as close as possible to the concrete casemates; additional men would drop immediately by parachute inside the defenses on top of the battery.

Outlining his plan to A Company, Otway asked for volunteers; the entire company stepped forward. Moved by this show of courage and selflessness, Otway and Major Allen J. M. Parry, the company commander, had the solemn task of selecting 60 men, all of them single, for almost certain death.

Practicing for Pegasus

As Otway was running 9th Para through its paces, Major John Howard and his glidermen were rehearsing for their coup de main assault to simultaneously take both the Bénouville and Ranville bridges over the Orne. The bridge at Bénouville was code-named “Pegasus” and the one at Ranville “Horsa.”

For months Howard had put the men of D Company through a grilling as they constantly practiced perfecting the techniques of seizing a bridge. Understandably, the troops became bored with the repetition, especially since, with the exception of Howard, they had no idea what their role in the invasion would be.

To end boredom and add a new level of realism, Howard asked Brigadier Nigel Poett if he could find a place in England that replicated the target in France––a place where two bridges close together crossed both a river and a canal. Colonel George Chatterton, commanding the Glider Pilot Regiment, said that such a place was found “near Hinton, Buckland and Bampton Aston which almost completely corresponded” to the Orne bridges area: the troops were moved there in early May to continue their training.

Fortune was about to smile on the Allies. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, head of Army Group B and tasked with defending the northern coast of France, had gone off to Germany to try and convince Hitler that the panzer units in Normandy needed to have the flexibility of countering local threats by the Allies when and where they appeared. Rommel knew that by going over his boss’s head––Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt—and meeting with Hitler he would incur the old man’s wrath, but he had to risk it; there was simply too much at stake.

Rommel also knew that Hitler, as well as the High Command, were firmly convinced that the Allies’ main thrust onto the continent would come at Calais, no matter how many thousands of landing craft and warships and paratroopers and gliders were hitting Normandy. Rommel’s meeting with Hitler produced nothing of substance; discouraged, he headed back to his Normandy headquarters at La Roche Guyon.

The defense of the Normandy coastline was primarily the responsibility of Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Richter and his 716th Infantry Division, an understrength division that was thinly stretched from the Dives River in the east to the Vire River in the west––a distance of some 50 miles, nearly the entire length of the Allies’ Normandy beachhead. The 716th was part of General of Artillery Erich Marcks’ LXXXIV Corps, which, in turn, was part of the German Seventh Army, commanded by Col.-Gen. Friedrich Dollmann.

Compounding the 716th’s problems was the fact that it had only two regiments (the 726th and 736th Grenadier), and both were of dubious fighting quality; many of its personnel were wounded veterans from the Eastern Front who had been transferred to Normandy to rest and recuperate.

In fact, so dire were the Germans’ manpower problems that one battalion of the 736th, whose headquarters were at Amfréville, even consisted of Russian soldiers who had been taken prisoner and given the option of either fighting for Germany or being interned in a prisoner-of-war camp; the loyalty and combat capability of this unit, known as Ost-Batallion 642, was doubtful at best.

The 736th Grenadier Regiment also had an artillery regiment, the 1716th, Battalion I of which was the one at Merville. The Merville garrison consisted of 80 artillerymen and 50 combat engineers. A forward-observation bunker with an excellent view of the coastline was located on the beach at Franceville-Plage.

The Merville battery was under the command of an inexperienced 24-year-old Austrian lieutenant named Raimund Steiner. The previous battery commander, Captain Karl-Heinrich Wolter, had been killed during an RAF bombing raid on May 19, 1944, while he was spending the evening with his French mistress. When he took command, Steiner had no idea that, in less than a month, his battery would be the scene of immense violence and bloodshed.

D-Day arrives

All the preparation and training was about to be put to the test. On the night of June 5, 1944, with warships and troop transports ploughing the stormy English Channel on their way to their assigned beachheads, the American, British, and Canadian parachute and glider forces were winging their way southward from their air bases in southern England.

Although dwarfed by the number of aircraft the Americans would be using 50 miles to the west, the 6th British Airborne Division lift was still considerable: a total of 266 aircraft, mostly Albemarles and Dakota C-47s, were detailed to carry 4,512 paratroops. The troop carriers were followed by 98 tugs pulling gliders. (Seventy-four gliders were successfully released, of which 57 landed on or near their designated Landing Zones. Altogether 611 troops were carried by gliders, and 493 of them successfully went into action.)

Once the skyborne soldiers were dropped, Allied battleships, cruisers, and destroyers would begin plastering the coastline with a fearsome barrage that would shake the entire coast of Lower Normandy, softening up the German defenses in preparation for the amphibious landing of over 100,000 soldiers.

According to the Overlord plan, Otway and his troops would depart from RAF Harwell (recce and rendezvous parties under Major Allen Parry) and Brize Norton (main assault group) shortly before midnight on June 5 in C-47s, Albemarles, and Stirlings––followed immediately by the rest of the battalion being towed in eight gliders.

In the early hours of June 6, dozens of frantic calls began lighting up the switchboard in the headquarters of Panzer-Grenadier Regiment 125 at Bellengreville, east of Caen. Roused out of bed, 32-year-old Major Hans von Luck, regimental commander, recalled, “I looked out the window and was wide awake; flares were hanging in the sky. At the same moment my adjutant was on the telephone: ‘Major, paratroops are dropping! Gliders are landing in our section!’”

Luck dashed to his command post, where he was inundated with calls from shouting captains and lieutenants telling him that countless airplanes were overflying their positions; they could see gliders and paratroopers. Everyone was convinced that this was the prelude to the long-awaited Allied invasion.

Luck relayed this information to his higher headquarters—Maj. Gen. Edgar Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer Division—but was told the general and his staff were on the road, heading back from Paris. Luck gave the junior officer who answered the phone “a brief situation report and asked him to obtain clearance for us for a concentrated night attack the moment the divisional commander returned.”

By the time Feuchtinger got the message, however, it was too late. Besides, the German high command was still clinging to the belief that any thrust at Normandy would undoubtedly be only a diversionary action to cover the real invasion that would take place at the Pas de Calais.

Soon, some of the 6th British Airborne Division paratroopers captured at Troarn were taken to Luck’s HQ and interrogated; intelligence was gathered that these troops were part of an effort to secure the bridges at Ranville and Bénouville in advance of a seaborne landing. Luck passed on the information to higher headquarters, which did nothing about it.

Lt. Col. Terence Otway and his 9th Parachute Battalion were on the way to their objective. One historian would call Otway’s assault on the battery “the most singularly outstanding example of personal leadership and raw courage displayed in Normandy during the pre-dawn darkness of D-Day,” and he would not exaggerate. Nowhere else during the entire invasion would so many things go wrong for the attackers, and nowhere else would so much chaos and adversity be overcome by so few.

Like their American counterparts, the British paratroops were weighted down with every conceivable item they might need for several days in combat. But whereas the American paratroopers used toy crickets to identify each other in the dark, the men of 9th Para carried bird whistles, and the officers had bakelite devices that made a quacking sound when squeezed.

As he crossed the Channel, Otway continued to run over the details of his mission; he and his parachutists, along with the supporting company of Canadians, would drop at DZ “V,” march a mile and a half to the northwest, and take cover as a hundred Lancaster bombers plastered the battery.

With the battery’s garrison dazed and deafened by the bombardment, or so Otway hoped, the rest of his force would arrive atop the battery in gliders, then blow their way through whatever mines and barbed wire remained with Bangalore torpedoes and assault the German survivors. The battalion would need to neutralize the battery no later than 5:30 a.m. Otway would then fire a yellow flare signifying success, or else the Royal Navy would begin shelling it.

Assaulting Merville

Trailing the paratroopers were the eight Horsa gliders. Piloting the first of them, Chalk Number 67, was Sergeant Billy Marfleet, a former dentist’s apprentice with a knack for flying. Number 67 was being towed by an Albemarle piloted by Flying Officer Christopher Lawson. Before they had taken off, Marfleet, along with the seven other glider pilots, had downed a huge meal of bacon and eggs.

The special treatment continued; the pilots were then trucked to their gliders at the airfield (they had always walked before). Shortly before 11:30 p.m. on June 5, the squadron received the signal to take off and so, with Lawson and Marfleet in the lead, the Albemarles and their attached Horsas began rolling down the runway until they became airborne. The unit assembled over Worthing near the south coast of England and then set course for France.

The flight over was as uneventful as a flight into history could be. The paras were so tightly wedged into the gliders that they could scarcely breathe, let alone move. But the bobbing and weaving motion of the gliders, being tossed about in the slipstream of the planes towing them, led inevitably to motion sickness, and soon the floors of the eight Horsas were awash in vomit.

Shortly after take-off, another glider, this one carrying men of Lieutenant Hugh Smythe’s No. 3 Platoon, A Company, had problems. The tow rope parted company with the tug, but the glider pilot was able to make a safe return to England; they would not arrive at the Le Mesnil crossroads until the evening of June 6, however.

The flight over the Channel was not without tragic mishap. Halfway across, the planes ran into a cloudbank as thick as steel wool. As the tugs and gliders approached the Normandy coast, deteriorating weather engulfed the formation. At some point while flying blindly through the dark, nighttime clouds, the tow rope connecting Number #67 with Albemarle V-1746 broke.

Billy Marfleet and his co-pilot Vic Haines dropped lower in hopes that they would see land beneath them. No such luck; all they saw was the blackness of the Channel below, rushing up at them.

Without an engine, and without the ability to climb, Number #67 plunged into the water, killing everyone on board. It was the first bad omen that signaled Otway’s aerial assault was headed for trouble. But, without radio contact between the gliders and the bombers carrying the paratroops, Otway was unaware of the tragedy that had just taken the lives of a glider full of his men and removed a key element from his assault force. He and the rest of the flight continued toward Normandy.

As his plane droned on, Otway, still trying to convince himself that the plan was workable, pulled out a bottle of whiskey that he had tucked into his jump smock and passed it around to the 20 men in his stick; it came back to him half-empty.

A few minutes after midnight the flight reached the sleeping coast, which suddenly began winking with flashes of light, and the anti-aircraft shells stabbed upward in angry red rivers to explode in and around the flock of planes. The pilot of the lead plane began to toss it about violently, throwing the paratroopers, who had just stood up in preparation for the jump, around like marbles in a tin can. Otway struggled forward to the cockpit. “Hold your course, you bloody fool!” he angrily shouted at the pilot.

“We’ve been hit in the tail,” the pilot shouted back.

“You can still fly straight, can’t you?” Otway barked. Then he saw the green light go on and the men starting to bail out through the hole in the fuselage. He thrust the half-empty whiskey bottle at one of the RAF crewmembers. “Here—you’re going to need this.” With that, he jumped to join his men.

As he drifted down toward a farmhouse that he recognized from the briefings to be a German battalion headquarters, Otway could see that the wind was carrying him away from the hump of the Merville Battery’s four casemates. With no time to steer his chute, he slammed against the wall of the house and dropped several feet into a garden where two of his men already lay. A German, having heard the thud, opened an upstairs window and looked out. Seeing movement, he fired at the Brits; one of the Brits responded by tossing a rock through the window.

Otway and the two men then high-tailed it out of the garden and took cover nearby while the Germans inside the house rushed out to look for whomever was disturbing their peace.

Meanwhile, the plane from which Otway had jumped was circling the area, for only seven men of his stick had managed to jump on the first pass; the pilot made two additional passes over the area.

Suddenly, on the ground, there was a loud crash of breaking glass. Otway’s batman, Corporal Joe Wilson, had just come down on top of the glass greenhouse attached to the headquarters farmhouse. Luckily, he managed to avoid being killed or captured by the Germans and took off for the battalion’s rendezvous point (RV) in the woods more than a mile from the battery.

Also moving to the RV, Otway managed to pick up a few 9th Para stragglers along the way, but, when he counted noses, he found that he had only a handful of troops. Waiting in the woods, Major Alan J.M. Parry, his second-in-command and the commander of A Company, whispered, “Thank God you’ve come, sir.”

“Why?” asked Otway, fearing the worst.

“The drop’s bloody chaos, sir. There’s hardly anyone here.”

It was true. 9th Para was scattered over more than 50 square miles; the bulk of the unit was missing, dropped into trees, marshes, flooded areas, and villages––everywhere except Dropping Zone “V.”

Otway waited, but at 2:35 a.m., nearly an hour and a half after the drop, only 110 of the battalion’s 750 men had been assembled.

Forty more stragglers came in during the next 15 minutes, but there were no jeeps, guns, trailers, anti-tank weapons, or, except for 20 lengths of Bangalore torpedoes and a few pounds of plastic explosive, no demolition equipment. The sappers, mortars, radios, signal equipment, mine detectors, and naval-bombardment party were all missing. And most of the Canadians of A Company, who were supposed to provide flank security, were nowhere to be found.

The Canadians had been badly mis-dropped. According to the Canadian Parachute Battalion war diary, Major Wilkins’ A Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, was dropped at approximately 1 a.m. but far off target. Upon tramping through the fields and reaching the company rendezvous point, Lieutenant John A. Clancy found only two or three men of the company present. After waiting unsuccessfully for more members of the company to appear, Clancy decided to reconnoiter the nearby village of Gonneville-sur-Merville. Taking two men, he entered the village but found no sign of the enemy. The Canadians would play no part in the coming battle for the battery.

Otway glanced at his watch again: nearly 3 a.m. The battery had to be taken by 5:30 or else the light cruiser HMS Arethusa would begin shelling it. The battalion had one Vickers machine gun, one Bren gun, and a Very flare pistol that, ironically, was only supposed to be used to signal the Navy once the mission had been accomplished.

Otway lay in hiding for a half hour observing the German sentries “wandering around inside [the wire], smoking, and they hadn’t got a clue.” But he was in a terrible quandary.

Should he wait awhile longer in hopes that the men and equipment he needed would show up or should he launch the attack with what he had at his disposal? Given the circumstances, no one would have blamed him if he decided to abort the assault and move on to his secondary objectives (of which there were many).

After more hopeful, fruitless waiting, Otway realized that he could not delay the assault any longer. He called for a meeting of his available officers and non-coms and told them that, despite their diminished numbers, the attack would proceed; all of his subordinates supported that idea, even though they knew many of them would likely die in the effort.

The force crept out of the woods and started moving silently toward the objective, bypassing an anti-aircraft battery firing on the two remaining gliders that were coming in to support Otway’s assault. At this moment, the two gliders swooped in low over the battery looking for a star-shell mortar signal that Otway could not give because his signaling equipment was missing.

The first glider, with Captain Robert Gordon-Brown and his platoon from A Company, 9th Para, aboard, took hits from the Germans as it raced overhead but landed safely, albeit four miles away.

The second Horsa, carrying Lieutenant Hugh Pond and his platoon, also from A Company, looked as though it would land atop the battery but then was ripped by 20mm anti-aircraft fire. It came in hard and fast in an orchard some 200 yards away, where trees tore off the wings and shredded the plywood fuselage. Dazed, the survivors stumbled from the wreckage only to come under fire from a German patrol.

After reaching the outer wire of the battery, Otway ran into Major George Smith, commander of Headquarters Company, who had parachuted in with the advance party. Smith reported that he was late because the pathfinders had marked the wrong DZ but that he and his recce party had already snipped the outer ring of barbed wire, dug up some of the mines, marked a path through the minefield by scratching grooves in the dirt with the heels of their boots, and were ready to cut the inner wire upon Otway’s order.

Smith also said that he had seen the hundred Lancasters flying overhead, but their bombs had completely missed the battery (they had dropped their bomb load on DZ “V” instead), and some of his men drifting to earth in their parachutes had the falling bombs miss them by feet.

As the awful reality that his mission was on the verge of unraveling sank in, Otway counted his force. Major Parry’s A Company and Major Ian Dyer’s C Company (Dyer himself was missing) could muster only 48 men total. Major Harold Bestly’s B Company was down to 30 men. With only about a third of his expected force available, Otway had no choice but to reduce the scope of his assault.

Dividing his reduced resources into four assault teams of 12 men each, Otway assigned each team to attack one of the enemy casemates. Only two gaps through the wire and minefield would be used instead of three, with two assault groups attacking through each. B Company was organized into two breaching teams of 15 men each, with 10 Bangalore torpedoes. A diversion party made up of seven men and the Bren gun would cause a commotion at the main gate to distract the German garrison.

Suddenly, before Otway could give the signal to attack, the Germans became aware of the Brits’ presence and began spewing out automatic-weapons fire. Otway yelled, “Get those bloody machine guns!” The Vickers opened up in reply and silenced the German positions.

In all the noise and confusion, Otway gave the order for the breaching teams to blow the wire. The Bangalores ripped a 20-foot gap and, before the dust from the explosion had settled, Otway shouted, “Get in! Get in! Get in!”

Major Parry blew his whistle and charged through the minefield with the assault party following on the double; he was among the first to be hit. “I was conscious of something striking my left thigh,” he said. “My leg collapsed under me, and I fell into a huge bomb crater. I saw my batman [Private George Adsett] who was just alongside me, looking at me as if to say, ‘Bad luck, mate,’ and off he went.” Adsett was killed moments later.

The four assault parties from A and C Companies rushed through the gaps, firing their Sten guns from the hip as they ran. Men threw themselves onto barbed wire so their mates could use them as human bridges, then jumped into the trenches to battle the Germans hand to hand.

The pre-dawn darkness was raked by a thousand bullets, and grenades and mines and shells were exploding everywhere, catapulting attackers into the air. Private Alan Mower saw a bleeding paratrooper sitting in the middle of a minefield, waving his comrades away and yelling, “Don’t come near me!”

Otway, observing all this from a bomb crater that he had made his command post, decided that his place was in the center of the action even if it would cost him his life, so he leaped up and shouted, “Come on!” to his batman Corporal Joe Wilson and made for the gap in the wire.

Otway’s officer corps was particularly hard hit in the first few minutes, although he himself was miraculously unhurt. His adjutant, Captain Havelock “Hal” Hudson, was hit in the buttocks and stomach; B Company commander Major Harold Bestly had a mangled leg; and Lieutenant Alan “Twinkletoes” Jefferson, so nicknamed because he had previously trained with the famed Sadler Wells ballet company, was wounded by a mine.

Major Parry, too, was down and lying wounded in a bomb crater. “My left leg was numb, and my trouser leg was soaked in blood,” he said. “Having a miniscule knowledge of first aid I removed my whistle lanyard and tied it to my leg as a tourniquet. My knowledge was evidently too limited, as I applied it to the wrong place. Realizing, after a brief interval, my error, I removed it, thus restoring some form of life to my leg; sufficient at any rate, to enable me to clamber out of my hole and continue with my appointed mission.”

Private Sid Capon jumped into a trench where he was confronted by two men in German uniforms. Suddenly they threw down their weapons and raised their arms, shouting “Russki! Russki!”––indicating that they were Russian “volunteers” the Germans had pressed into service. Other Germans who noticed the paratrooper insignia on the Denison smocks, shouted “Fallschirmjager!” and either dashed into the night or surrendered.

The battle was reaching its climax. Lieutenant Mike Dowling of B Company led 40 men to the gun ports of one of the casemates, furiously firing their Stens and throwing grenades into the embrasures. Dowling said, “We started to charge and then I felt something whipping me on my left leg. I went down and I couldn’t get up. My left arm and left leg were both hit. I watched my soldiers going in … and they were doing what they should do. I was immensely proud of them.”

Other paras broke through the steel doors of one of the earth-covered gun casemates only to be cut down by German grenades. While some paras were finishing off stubborn pockets of resistance, others were rounding up prisoners.

Otway overheard one of the soldiers say, “‘Poor Mr. Dowling,’ so my ears pricked up and I said, ‘Mr. Dowling––what?’ ‘Oh, he’s dead, sir,’ he said. ‘So is his batman. I saw both their bodies.’ I said, ‘No! Are you sure?’ And he said, ‘Yes sir, quite sure.’ That was an awful shock.” But Dowling wasn’t dead, just badly wounded.

A couple of miles to the north in the coastal resort city of Franceville-Plage, as the attack on the battery began, the battery commander, Lieutenant Steiner, was sound asleep in his quarters at the beachside observation and command post. He was awakened by a frantic call from a sergeant at the battery telling him that gliders had landed at the guns and that a fierce battle was underway, with grenades and phosphorus bombs being thrown down the casemates’ ventilation shafts.

“Over the telephone,” Steiner said, “I heard my men panting as if in the last hour of their lives. Some prayed, others cursed and fought against suffocation.”

Steiner quickly called his boss, Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Richter, to inform him of what was taking place. Richter was not impressed. “Typical Austrian,” Richter grunted before he hung up, noting that, to the Germans, the Austrian soldiers were “wimps” and easily panicked into thinking that a single downed glider meant that the invasion had begun.

“I did not know what to do,” Lieutenant Steiner admitted. “I was still a very young lad and was all alone. It was hopeless.”

He then rang up the commander of the 711th Division, who said that he could provide artillery support but that Steiner had to get to his battery immediately so he could adjust the fire. The lieutenant recalled, “The radio operator and I crawled a mile on the belly. In the meantime, it was a pitch-black night. Chaos. Franceville, the classy seaside resort between the [Command] Center and the battery, was burning already. We crawled through the middle of the inferno.”

As he neared the battery, Steiner saw dead and wounded soldiers from both sides scattered across the landscape and German artillery shells raining down on it (someone else in one of the casemates must have been calling down fire on the site), trying to blow away the enemy. He realized he had no chance to do anything and so retreated back to the coast.

“The bombers came and went, gliders behind them,” he said. “It was hell. Everywhere were paratroopers––whether English, whether American, I do not know to this day. We were shelled all the time and had to defend ourselves. Constant artillery strikes and shots came from all sides. It was heartbreaking.” Later he tried again to reach the battery, but it was no use, and once more he went back to the command center on the coast, feeling that he had failed in this, his first battle.

At the battery, Major Parry, his leg bleeding profusely, hobbled over to No. 1 casemate and noticed some captured German prisoners sitting huddled together. “Most of them were wearing greatcoats and soft hats and didn’t appear to be expecting us,” he said. “As I entered the enormous casemate it was possible to discern only two or three of my party.

“To my intense dismay, I saw not a 150mm gun, as was expected, but a tiny, old-fashioned piece mounted on a carriage with wooden wheels. I estimated it to be a 75mm and it was clearly a temporary expedient pending the arrival of the permanent armament. This was an awful anti-climax and made me wonder if our journey had really been necessary.”

Pondering the situation and weak from loss of blood, Parry was resting on the sill at the bottom of the firing aperture resting when, moments later, there was an explosion outside, and he felt something slam into his wrist. At first thinking that he had lost his hand, Parry was relieved to find that it was only a small cut from a shell splinter. He bandaged it and proceeded to deal with the captured gun.

“We all carried sticks of plastic explosive, detonators, and fuse wire, and I instructed a sergeant to make up a suitable charge which was placed in the breech of the gun.” The fuse was lit, and everyone abandoned the casemate until a tremendous bang was heard. “We re-entered the casemate, now full of acrid smoke, and upon inspecting the gun I was reasonably satisfied that sufficient damage had been inflicted upon it to prevent it playing a part in the seaborne assault.”

The rest of the guns were disabled, but Otway’s men were not yet home free. Artillery rounds from a nearby battery began saturating the area.

It was almost 5 a.m., and the eastern sky was growing light. In a half hour the cruiser Arethusa would add its bombardment to that of the Germans. Lieutenant Jimmy Loring, Otway’s signal officer, fired a yellow flare from the Very pistol and lit yellow smoke candles in hopes that an RAF spotting plane would see the success signal and radio the cruiser lying offshore. It did.

Loring also produced a ruffled carrier pigeon from a case inside his smock, attached a success message to its leg, and sent it on its way. After first heading toward Berlin, the bird corrected its direction of flight and made for London, carrying the news that the battery had been neutralized.

In less than an hour, the battle for the Merville Battery was over, but victory came with a heavy price. Otway, his ears still ringing from all the noise, and his fury at the pilots for the mis-drop undiminished, paused to count his losses. Of the original 150 attackers, only 75 were still on their feet; the other 75 lay dead or wounded around the battery.

The Germans had it worse. Out of the original 200, only 22 survived. Corporal Doug Tottle, one of only six out of 30 medical orderlies who made it to the battery, thought he could stand the sight of anything, but the carnage––men disemboweled, some missing eyes, jaws, arms, and legs, others decapitated––sickened him. “I then helped and did what I could with the aid of the other medics,” he said.

Because he had a large number of wounded men to be cared for––both British and German––and no ambulances, jeeps, or necessary medical equipment, Otway asked the battalion’s medical officer, Captain Harold Watts, and two medical orderlies if they would set up an aid station in a half-destroyed barn at a farm near the battery, known as Haras de Retz, realizing full well that they might themselves be captured; the men agreed.

More German shells from a battery to the west began falling around the position, so Otway issued orders for the battalion to quickly head to the appointed assembly point—a large wooden crucifix about 500 yards away. He knew that his depleted force was in no shape to take on its secondary objective—a small radar station at Sallenelles—but perhaps they could make it to Le Plein, a mile to the south.

The wounded Parry was trundled off the battlefield in a small cart towed with toggle ropes. Major Smith noted that Parry “took a brandy flask from his pocket, gulped a mouthful and beamed, ‘A jolly good battle, what?’ The grim faces of the men burst into smiles, and the sullen group of prisoners looked on in bewildered amazement. Parry insisted on being allowed to stay with the Battalion, but Otway ordered him to go to the Regimental Aid Post, and he did so reluctantly.”

Private Ken Walker soberly reflected on the battle and its aftermath: “Here for the first time I realized some of the horrors of war, never having been in battle before. I was absolutely exhausted and feeling depressed, as if suffering from the after-effects of an attack of influenza. Most of the soldiers appeared to be in the same state, which could also be described as total bewilderment.”

Their work at Merville done, Otway and his gallant band, their mud-covered, blood-stained uniforms shredded by bullets and shrapnel and barbed wire, began heading toward Le Plein.

While on the march, Otway met up with Lieutenant Pond’s glider-borne platoon, which had engaged a German patrol after its crash. A German doctor and two orderlies were Pond’s prisoners, and they were marched back to the barn to assist Captain Watts. (When the medical teams ran out of supplies, the German doctor said there were more in a bunker and went to retrieve them; the doctor was killed by a German shell.)

Aftermath

Lieutenant John A. Clancy of A Company, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, whose unit was dropped far from the battery, finally arrived at the RV at approximately 6 a.m. and found one other officer and 20 other ranks of the battalion and several men from other brigade units there. By that time, of course, the fight for the battery was over.

Major Hans von Luck, commander of Panzer-Grenadier Regiment 125, was angry and frustrated. “If Rommel had been with us instead of in Germany,” he later said, “he would have disregarded all orders and taken action—of that we were convinced. We felt completely fit physically and able to cope with the situation …

“There was no longer much chance of throwing the Allies back into the sea … Even the bravest and most experienced troops could no longer win this war. A successful invasion, I thought, was the beginning of the end.”

When Otway and his battered-and-bloody 75-man battalion reached Le Plein, they were at the end of their rope. He recalled that, while on their way there, they were accidentally bombed by a squadron of British bombers; luckily, there were no casualties, but his already considerable rage against the RAF hit a new high. What was left of his unit would remain in Normandy until September, when it was brought back to England.

Each attacking unit of the Allied invasion force played a role, whether large or small, in the ultimate Allied victory. And none fought with more courage and gallantry than Terence Otway’s 9th Parachute Battalion.

This article is adapted from the author’s book, If Chaos Reigns: The Near-Disaster and Ultimate Triumph of Allied Airborne Forces on D-Day, 6 June 1944.

Enjoyed the read. Very good account and detail