By Stephen D. Lutz

On September 27, 1944, a C-47 Skytrain named “Mary,” tail number 43-48395, prepared to depart Royal Air Force Base Wharton in Lancashire, England, filled with assorted medical supplies destined for a U.S. Army field hospital in northeast France. After delivering the supplies, “Mary” was to have been loaded with wounded American soldiers and flown back to a hospital in England.

“Mary” was under the command of 1st Lt. Ralph Parker and co-pilot 2nd Lt. David Forbes. Two enlisted men were also on board: Sergeant Harold Bonser, the flight engineer, and Corporal Chester Bright, the radio operator.

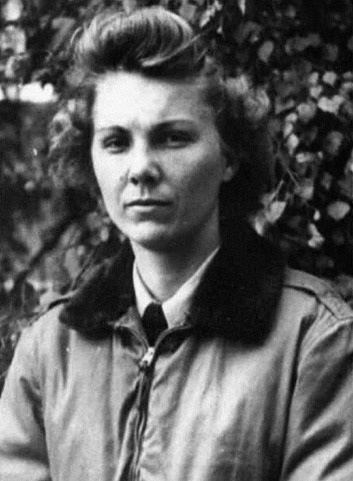

Also on board was flight nurse 2nd Lt. Reba Zitella Whittle of Rocksprings, Texas—140 miles west of San Antonio—and surgical technician Tech-3 Jonathan Hill. The 25-year-old Lieutenant Whittle was an experienced flight nurse; this was her 40th flight. While there was not much for her to do on this leg of the journey, she knew that coming back she would have her hands full caring for a planeload of wounded men, many in agony.

In the late 1930s, before the war began, Reba had completed the nursing course from Medical and Surgical Memorial Hospital’s School of Nursing in San Antonio, then invested another year at North Texas State College in Denton, Texas, studying Home Economics.

On June 10, 1941, Reba attended the Army’s primary medical post at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio for an Army induction physical. Standing five-feet five-inches tall and weighing a mere 117 pounds, she was easily disqualifiable for being underweight for her height. Only under advisement of increasing her calorie intake to gain an extra seven pounds was she able to meet the requirements for military duty as a registered nurse. She was commissioned a second lieutenant and given Army serial number N-734426, with the “N” designating “Nurse.” Her date of enlistment was June 13, 1941.

After serving at the Albuquerque Air Base Hospital, she spent 27 months working at the Station Hospital at Kirkland Field, New Mexico, and at Mather Field near Sacramento, California. She then volunteered for overseas duty. In August 1943, she was enrolled in the Army Air Forces School of Air Evacuation at Bowman Field, Kentucky.

She attended the six-week school and learned a variety of duties and responsibilities that would be hers once she reached the European Theater. She graduated in November 1943 and, on January 22, 1944, joined 25 other flight nurses aboard the ocean liner HMS Queen Mary for the trans-Atlantic crossing to England.

Once there, she was assigned to the 813th Medical Aeromedical Evacuation Transportation Squadron (MAETS) of the 310th Ferry Squadron, 27th Air Transport Group. For the next nine months Reba found residency upon three Royal Air Force bases: RAF Nottingham, RAF Brighton, and finally RAF Grove outside of Oxford, northwest of London.

Reba came to a realization of hazards connected to being a military flight nurse when she read a book written by Juanita Redmond, who had been an Army nurse in the Philippines when Japan invaded on the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. Redmond managed to escape the islands via a U.S. submarine to write her tales in the book, I Served on Bataan (Lippincott, 1943). By war’s end, 201 American nurses were killed. Within the collective of the 813th, nurses never openly discussed such consequences of war.

That all changed on the fateful day of September 27, 1944.

Strapped into her seat in the unheated fuselage of the cargo plane named “Mary,” Reba closed her eyes for the two-hour flight, and began drifting off to sleep, lulled by the loud drone of the two Pratt & Whitney engines.

At this point of the war, the Western Allies were pushing the German Army ever eastward. Heavy fighting had taken place from September 17-25 during Operation Market Garden, a bold-but-flawed plan hatched by British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery that was intended to cross the Rhine River and push into northwest Germany.

But the operation had not gone as planned, and so the Allied drive became stalled, with heavy casualties.

The drowsy lieutenant had no idea that the plane was 60 miles off course, having overflown the airport where it was supposed to have landed and was now approaching the German city of Aachen and its protective screen of 88mm anti-aircraft gun batteries.

Since the plane, in accordance with U.S. Army policy, was not marked as a medical evacuation plane, the Germans below saw it as just another C-47, a viable air target worthy of being shot down.

Suddenly, the ear-punching booms of 88mm shells blotted out the roar of the plane’s engines, and shards of white-hot shell splinters ripped through the plane’s thin aluminum skin.

In her diary, Reba wrote, “Was sleeping quite soundly in the back of our hospital plane until suddenly awakened by terrific sounds of guns and cracklings of the plane as if it had gone into bits. For a few moments I hardly knew what to think…. Looked at my Surgical Tech [Hill] opposite me with blood flowing from his left leg. The noise by this time seemed to be much worse. But to see the left engine blazing away is simply more than I can express.

“Started to scream and cry as most women would, but Sgt. Hill consoled me and assured it wouldn’t help—at that time I realized no value would be of benefit and he had been injured and should be the one crying. About that time he was hit in the left arm as I had my head on is left shoulder.”

Jolted as though slugged with a giant boxing glove, “Mary,” with six persons aboard, began a sharp descent to earth.

Luckily, the pilots were able to maintain a semblance of control and managed to bring the damaged plane in for a crash landing. Reba flew forward and smashed into the navigator’s compartment head first. She wrote, “The ship was nearly blazing and holes every place, some large enough to crawl through back in the fuselage. Noticed the others crawling out the top hatch, so immediately went zooming out. Three out before I—the pilot last—who fell as if he had been badly wounded. One never came out.”

German soldiers quickly surrounded the plane and watched as four of the five persons on board stumbled out; all made it except for radio operator Chester Bright. A German soldier wrapped a bandage around Reba’s bleeding head. The five survivors were taken into custody as prisoners of war.

Reba Whittle was woozy from a concussion and bleeding from a gash to her forehead. Her surgical technician, Jona-than Hill, was bleeding severely from injuries to his left arm and leg. The others—Parker, Forbes, and Bonser—were shaken but relatively uninjured.

With weapons drawn, the German troops herded the Americans together and marched them to a house “where we went into a dank dungeon cellar which really looked very spooky and smelled very bad.” A doctor came in and provided some immediate first aid.

The group was then marched for two or three miles to a village on the outskirts of Aachen, then stopped at a brick house. Reba wrote, “Marched us in where four or five German officers sat in this office. There we stood like dummies and them giving us terrific glares. They showed us immediately to another room where the guard gave the Sgt. a glass of wine. Before he had time to complete his wine, they pushed us outside. There we sat on the ground shivering as it was rather cold . . . We had to sit outside there for some time, until a queer-looking truck came up and they motioned for us to get in.

“Never a word between the guards and us as neither could understand,” she said. The truck arrived at a larger village and the prisoners were herded into a barn, where they were given some pears to eat. An officer who spoke good English came in and brought them into the kitchen of the farmhouse and gave them some more food and drink. Being a woman, Reba was of particular interest to the officers.

After their meal, the POWs were taken on a 40-minute bus ride to “a huge-looking place surrounded by a very high metal fence and a guard at the gate to let us in.” After more food, the five Americans were led to dirty rooms, where Reba was allowed her own room (with straw mattress) and the four men in another; afraid of being alone, she moved in with the four men.

An interrogator arrived and began asking questions. “The air-raid alarm came and he said, ‘Well, too bad—you might be bombed by your own people.’ And out he went. This night was the longest I ever spent.”

The next day the group was taken by truck, and prisoner Reba was subjected to stares by the villagers in each town they passed through. At one stop a German doctor looked at her and shook his head. “Too bad having a woman, as you are the first one and no one knows exactly what to do,” he said in English.

For nearly five months, none of the Germans knew what to do with Reba Whittle. Germany was signatory to the Geneva Accords pertaining to the health and welfare of POWs and felt compelled to provide some degrees of safety and comfort as best as war conditions allowed.

The journey continued, with the truck finally arriving at an airfield. Reba noted, “The city was very badly damaged. Could hardly see a house or building that wasn’t torn up.”

By now her injuries and fear of the unknown were getting the best of her. She was put alone into the room of a house. “This is when I really first let down and cried. They couldn’t figure out what was wrong with me. So I asked for my Surg. Tech [Hill] to be put in there with me. Felt much better when he came in but couldn’t stop crying for quite awhile.”

For the next few hours, Reba and the others were questioned by their captors, then sent by night train to Frankfurt am Main—and a Luftwaffe intelligence center at Oberursal, just outside Frankfurt. Reba was separated from her male companions and locked in a cell. “Extremely depressing,” she said. “The more I thought of being in a cell and wondering what would happen next, I became terrified and started crying. Felt more like screaming and a perfect wonder I didn’t.”

A couple of German officers came in. “Took my name and said how sorry they were to have a nurse as a POW as they had no facilities at all. [They] asked some questions and said I would go to a hospital nearby, and they had a few of our boys there.”

Reba was taken to the hospital, where she was allowed to bathe. A British gentleman, possibly a doctor, gave her clean men’s clothing for her to change into. After he left, she was locked into a room and became hysterical. Gradually she calmed down and the nurses there brought her flowers, fruit, and bobby pins for her hair.

On the morning of October 6, Reba was taken on an all-day trip to a hospital in Obermassfeld, near Weimar. She said, “This was a British and American [POW] hospital run by British doctors.” Here she was asked by the doctors if she would be able to perform some nursing duties; she agreed. “All the boys seeming very glad to see an American nurse,” she wrote, “plus being greatly surprised and all anxious to hear how I was taken [prisoner].”

Reba recalled, “Shall never forget one of our boys by the name of Davis from Dallas who had lost his right arm. His kind words and hospitality was really appreciated. Then to see how he made himself so useful after having an arm off was remarkable.”

Soon she was off to another hospital, this one in Meiningen—Stalag 9-C—between Frankfurt and Leipzig. The hospital was a large building that had been a concert hall before the war; the patients were a mixture of Americans and Brits. She said that she “felt very out of place being among 500 men.” She went to work in the Burn Unit and wherever else she was needed.

The staff of the hospital went out of their way to make her comfortable—hung framed pictures on the wall in her room, installed curtains, brought in or made a table, cupboard, and even an easy chair. A South African gave her a bottle of perfume that he had carried through Sicily and Italy; he had been a POW for four years. Someone came up with a tube of lipstick. “They all actually were too good to me. Always trying to get or make something to be more comfortable and make me happy,” she wrote.

In late October a group from the International Red Cross inspected the hospital. As stipulated within the Geneva Accords, such visits were routine in determining which disabled prisoners could be repatriated due to disabilities that eliminated them from all active combat/military duty. Reba missed that visit but her name must have been mentioned. Four weeks later, another delegation visited specifically looking to meet her.

By mid-November a tri-party negotiation was in process between German and American diplomats, with the Swiss Red Cross as mediators, to come to terms in exchanging Reba for approved German POWs. The last entry Reba made in her journal came on November 23, 1944.

Reba’s diary concludes at that point possibly because she learned that the International Committee of the Red Cross was working on ways to repatriate her back to the U.S.

Delays in repatriation were common, so it was not until January 1945 that she was told that she was being exchanged for German POWs. She left Stalag Luft IX on January 25, accompanied by members of the German Red Cross, and was placed in a railroad boxcar with other prisoners, some of whom seemed to be psychotic.

After arriving in Bern, Switzerland, she was housed by a Swiss couple; there she had her first hot bath in months. The following day she was repatriated with 109 other American POWs and on February 2, 1945, flew from Marseilles to the U.S.

She arrived via a military C-57 Lodestar transport plane and was admitted into Walter Reed Hospital on February 5. She was immediately transferred to Brooke General Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, as that was her home state.

After a brief reunion with her fiancé, Lt. Col. Stanley Tobiason of the U.S. Army Air Force, she received a “welcome home” telegram from President Franklin D. Roosevelt and a security debriefing. She also received a Purple Heart and the Air Medal. On March 2, 1945, she was promoted to first lieutenant after spending four years, two months, and 13 days time in grade as a second lieutenant.

By May 11, 1945, she was classified as fit only for light duty due to dizzy spells and anxiety flare-ups.

Reba also spent several months in and out of Army hospitals to treat medical conditions brought on by the plane crash and her incarceration as a POW. Because of severe headaches, she was disqualified from flying.

In August 1945, she married Lt. Col. Tobiason. (At one point after the crash, he received permission to make a voluntary search-and-rescue mission for her but failed in his attempt.)

She was honorably discharged from active duty on January 13, 1946. Immediately thereafter, she applied to the Veteran Administration for war-related combat-injury disability compensation for a variety of physical and psychological ailments, including PTSD, that were brought on by the crash and her time spent as a prisoner of war.

Her biggest battle came against the U.S. Army. In 1950 she initiated a ten-year, back-and-forth claim for service-related medical-retirement benefits. The Army repeatedly denied appeal after appeal. Hospital stays in both civilian and military facilities would not sway the Army’s opinion that her injuries not incurred under battle conditions, despite the fact that she was shot down while on active duty over enemy territory.

Through a series of three settlements, Reba received a total payment of $13,760.66, but nothing toward a monthly income disability benefits. By 1960 she gave up that battle.

On January 26, 1981, Reba Zitella Tobiason, neé Whittle, died due to brain cancer. The organic nature of this cancer may, or, may not, had been linked to her massive brain concussion of September 27, 1944.

Nearly 94,000 American men were taken prisoner during the war in Europe, but 2nd Lt. Reba Zitella Whittle was World War II’s only American female military person to be held as a prisoner of war in all of the European Theater.

The majority of Reba’s history and diary comes from Lt. Col. Mary E. V. Frank’s The Forgotten POW: Second Lieutenant Reba Z. Whittle, A.N., February 1990, Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments