By David H. Lippman

In the darkness, the two American submarines moved toward the hostile beach, inching carefully through badly marked waters. They surfaced well before dawn, and the Marine Raiders and submarine crews began bringing up rubber boats from below, inflating them on deck, installing outboard motors, and filling them with the Marines’ ammunition and supplies.

It was the early morning of August 17, 1942, and a team of U.S. Marine Raiders, led by a Corps legend and the son of the president of the United States were going to launch a raid that would boost morale in America but have an unexpected blowback a year later—leading to the deaths or wounding of 3,000 more Americans.

As the invasion of Guadalcanal opened on August 8, 1942, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific, was determined to keep the Japanese off balance and unable to respond properly. A raid on Makin (pronounced “Muckin” or “Muggin”), one of the Gilbert Islands, a British colony seized by the Japanese after the outbreak of war, seemed just the ticket.

Assigned to do the job was the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, under a colorful, leathery, hawk-nosed, 46-year-old major named Evans F. Carlson. Son of a Congregationalist minister, he had joined the Army at age 16 to fight in the Great War and risen to the rank of captain. In 1922, he joined the Marines and was commissioned as a second lieutenant the following year.

At a time when most American troops were enjoying leisurely peacetime routine, the Marine Corps was seeing a lot of action, fighting in what today would be called “peacekeeping missions” in Central America and the Caribbean or defending American holdings in China. Carlson was in the middle of this, earning his first Navy Cross in Nicaragua fighting “banditos.” He did a China tour in 1927-1929 and again in 1933-1935. After that, he was second in command of the Marine Guard at the Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia, where he caught the eye of and made a great impression on President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

When Carlson was sent to China for his third tour in 1937, FDR asked the lean major to provide personal reports to the White House on the volatile situation. Carlson reached Shanghai on July 7, 1937, a week after the Japanese invaded the city. From the safety of the International Settlement and its Marine Barracks, Carlson had a grandstand seat for the unparalleled savagery of the Sino-Japanese War, writing weekly detailed reports.

In November 1937, Carlson headed for Yenan in Shensi Province to study the Communist Chinese guerrillas to see if their operations matched their press releases. He marched with the legendary 8th Route Army for months and sent home vital information. The good side was that he reported that the Communists were an outstanding force. The bad side was that he reported that the Communists and Nationalists were working together to save China. Either way, two things resulted: FDR was able to provide arms to Nationalist China despite the Neutrality Act, and Carlson gained numerous ideas for developing a Marine force based on the Communists’ guerrilla principles, down to their slogan of “Gung Ho,” which meant “Everybody works together.”

After returning from China, Carlson resigned his commission, wrote two books on the China situation, and then rejoined the Corps as a major in the Reserves in April 1941. By this time Roosevelt was becoming intrigued by the exploits of the British Commandos in Europe and wanted to create similar forces under American auspices. The Army was developing the Rangers, but Roosevelt, who regarded the Navy as “us,” wanted such a force under its command.

The result was two battalions of Marine Raiders, and the 2nd Raider Battalion would be headed by Carlson himself. Another celebrity would be the battalion’s executive officer, Marine Reserve Major James “Jimmy” Roosevelt, the president’s son, who had served as assistant naval attaché in London and an observer with British forces in the Middle East. In London, he had had ample opportunity to study British Commandos, while in Cairo he had pored over the work of the legendary Long Range Desert Group and the Special Air Service.

Despite this colorful and knowledgeable leadership, the top Marine Corps brass was not impressed by the new battalions. They smacked of gimmickry, and high-ranking officers questioned the value of assigning the Corps’ best men to light units that would be sent on near-suicide missions. A strong answer came in the Corps’ own history—its first action in March 1776 had been a raid against British forces at New Providence Island in the Bahamas. Raiding was part of the Marine heritage.

The 2nd Raider Battalion got down to business on February 5, 1942, forming up at Camp Pendleton outside San Diego. Three thousand Leathernecks volunteered for 1,000 slots and were hit with Carlson’s tough question: “Could you slit a Jap’s throat without warning?”

Carlson ran a loose outfit, relaxing traditional forms of military command and discipline, adopting the communal methods of the 8th Route Army. Fully trained, the battalion was sent to Hawaii in May, baffling Nimitz, who later said, “Here I was presented with a unit which I had not requested and which I had not planned for.”

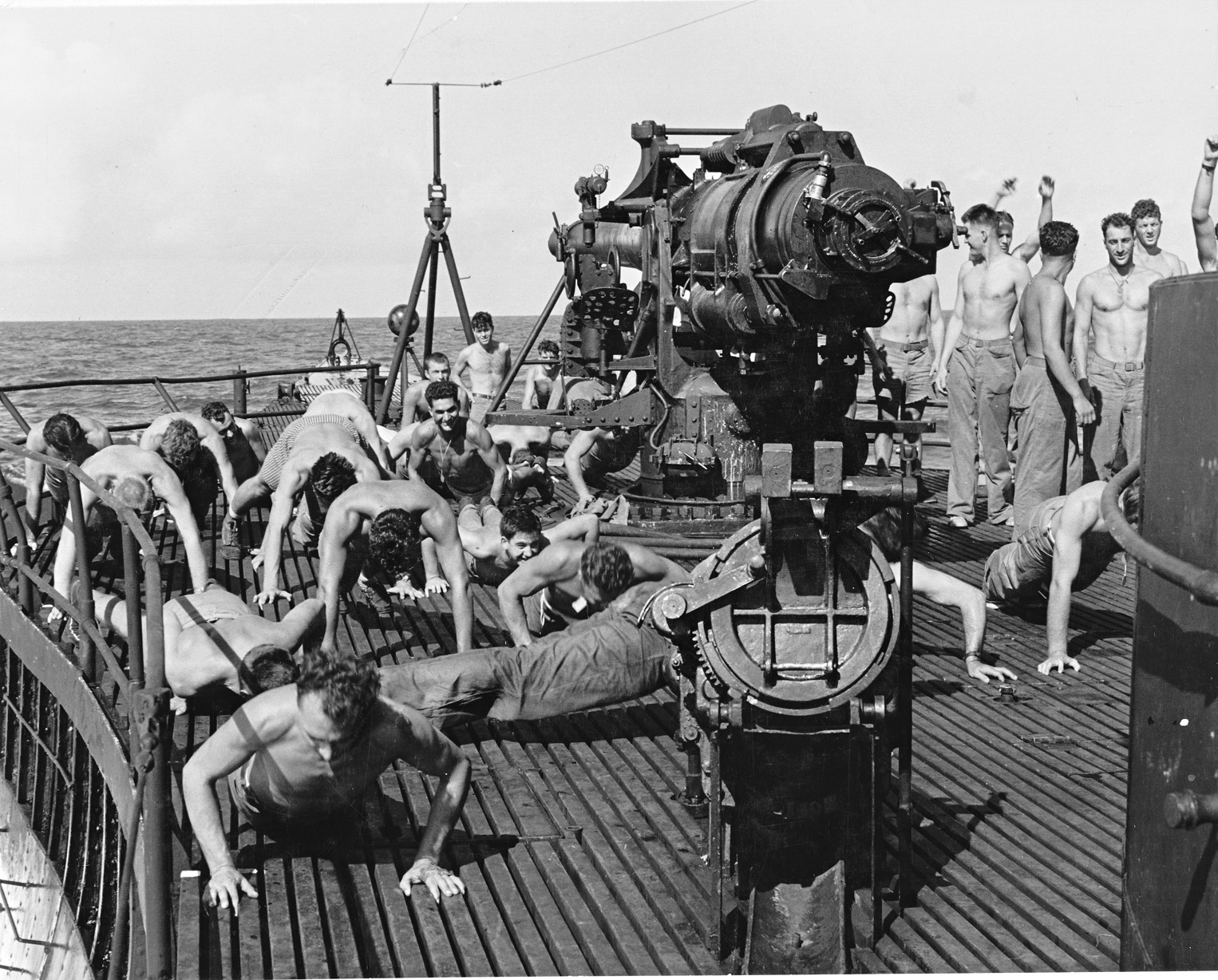

Nonetheless, he quickly found them a job—sending C and D Companies to Midway Island to defend that atoll from the expected Japanese invasion. Carlson’s Raiders provided color and dash to the defense, with their bandoliers of cartridges hanging from bronzed shoulders, belts bristling with knives, and pockets bulging with grenades. Even the medics went fully armed.

The Raiders worked hard at everything from hurling knives into trees to display their prowess to unloading supply ships to manufacturing antitank mines. Demolitions officer Lieutenant Harold Throneson and several Spanish Civil War volunteers developed an antitank mine from dynamite and a flashlight battery that exploded from 40 pounds of pressure. The Raiders delightedly manufactured 1,500 of them in a matter of days. Another Raider created booby traps from cigar boxes loaded with nails, spikes, glass, and rocks with a small charge of TNT. They could be exploded either electrically or by firing a rifle at a bull’s-eye painted on the side of the box. Other Raiders armed themselves with 14-inch screwdrivers that normally were used to repair PT-boat engines. A Raider explained that they were “good for the ribs, if you know what I mean.”

In the end, though, the preparation proved unnecessary. The Japanese force headed for Midway Atoll suffered a crushing defeat, losing four aircraft carriers and its air umbrella, and the invaders withdrew, never actually coming ashore. The Raiders left too, returning to Hawaii, and Nimitz searched for suitable employment for them.

That turned out to be Makin, part of the Gilbert Islands chain, which was an atoll about six miles long and half a mile wide, 2,000 miles west of Pearl Harbor, guarded by about 45 Japanese troops. In addition to the usual tasks of intelligence gathering and installation destruction, Carlson’s raid would distract the Japanese high command from the battles on Guadalcanal, making Tokyo think the Americans were opening a new front in the Central Pacific.

Carlson assigned 222 men to the operation, who would travel to the island on two large submarines, Nautilus under Commander Bill Brockman and Argonaut under Commander Jack Pierce. Neither sub had been much of a success so far. In addition to dealing with misfiring American Mark 14 torpedoes, both submarines were burdened with slow speed, slow diving, poor maneuverability, and engines that were at risk for crankshaft explosions. Argonaut had been designed as a minelayer and proved a flop in that role. Nautilus was the only American submarine to strike a blow at Midway, trying to torpedo the crippled Japanese carrier Kaga, but two fish missed, and the third’s warhead did not work. It shattered, popping loose the air flask, which gave shipwrecked Kaga sailors a life preserver. Now the two submarines were being converted for use as guerrilla transport and supply vessels by having their torpedo racks removed and extra air conditioning and tiers of bunks added. They would build a fine record in that critical role.

Commander John Haines would head the naval task force. Carlson assigned Company B and his own staff to Nautilus and Company A to Argonaut. The two submarines loaded up at Pearl Harbor on August 8, the day after the Guadalcanal invasion, and sailed off. It was an uncomfortable voyage for everybody. The air conditioning could not keep up, so Bluejackets and Leathernecks sweltered below decks, unable to sit or stand in the crowded spaces. Haines let the Marines go topside in small batches for 10-minute breaks in the sun. Soon the subs were hot and fetid from unwashed men and the heat of cooking—the chefs and stewards were on 24-hour watches, as it took three hours to feed all hands.

The voyage proceeded without enemy intervention, and on August 16 both submarines joined company off of Makin Atoll’s main island, Butaritari, defended by Warrant Officer Kyuzaburo Kanemitsu and 42 other Japanese naval troops. For Kanemitsu and his men Makin was a soft billet, far from the war, but a dull place. A few days before the Americans arrived, Kanemitsu’s superiors, worried about Guadalcanal, logically ordered a general alert, and Kanemitsu took those orders seriously. Every day his men held maneuvers and built nests for their rapid-fire Nambu machine guns as snipers prepared to climb coconut trees to eviscerate potential enemy invaders.

The seaward side of Butariti is a fringing coral reef, and Carlson chose at the last minute to land over the northern reef opposite the principal settlement, which lay on the lagoon only 1,500 feet across Butaritari. However, Carlson did not pass that on to Lieutenant Oscar F. “Pete” Peatross, who led 1st Platoon, Company B, and he and his 11 men would head for the southern beach.

In the predawn hours of August 17, the submarines surfaced in position, and the Marines and sailors broke out the rubber rafts, outboard motors, and combat gear for the assault. Before dawn, 15 motorized assault boats were speeding over the reef straight for Government Wharf against no Japanese opposition. Instead, they had to cope with heavy seas, which swamped the outboard motors. The Leathernecks tied their boats together to keep going.

Lieutenant Merwin C. Plumley led Company A southward and ran smack into the first Japanese defenders, arriving on bicycles and in trucks. The Japanese gave Plumley’s men a warm welcome with their rifles and machine guns, forming up a skirmish line.

When Carlson reached the beach, eight natives joined him and reported the presence of a Japanese 3,500-ton merchant ship and patrol boat in the lagoon. Carlson radioed to Nautilus and Argonaut to shell these two enemy vessels, but the message only got to Brockman, skipper of the Nautilus. He promptly turned his submarine’s six-inch guns on the Japanese vessels and hurled 65 shells at them. Everybody reported seeing the two ships sink, but incredibly Brockman was not given credit for the sinkings after the war.

Meanwhile, Carlson’s Company A was pinned down by Kanemitsu’s men. Carlson wasted no time. He sent Company B into action on the left flank, and Kanemitsu soon realized that his 45 men were badly outnumbered.

“All men are dying serenely in battle,” he radioed to his superiors. Even so, his snipers did their best, shooting at any American operating a radio, and his machine gunners fired their Nambus until they all died at their posts.

At 10:39 am, a Japanese reconnaissance seaplane turned up to find out what was going on, and the two submarines dived to avoid bombs. The reconnaissance bird was followed at 11:30 am by two more, which circled over the island looking for targets for 15 minutes. Finally they dropped some bombs on the sand, doing little damage, and headed home.

Meanwhile, Peatross, having landed on the wrong beach, tried to carry out his original orders to rendezvous with Company A at the island’s church. While doing so, he and his men attacked the island’s radio station, destroying the equipment. He found the Japanese were between him and the rest of his buddies but thought he could push through. He got to within 200 yards of the main Marine force, knocking out a Japanese machine gun and killing some of the enemy, including two fleeing in a car. But three of Peatross’s men were killed and several more wounded. Peatross moved over the ocean side of the island away from the lagoon and decided to wait for the larger force come to him. When that did not happen, he and his men withdrew to their boats and Nautilus, in that order.

Back at the main battle, 12 more Japanese planes of various types showed up at 12:55 to bomb and strafe the island with little success. Two Kawanishi “Mavis” flying boats landed 35 troops in the lagoon to reinforce Kanemitsu’s defenders. Alert Marines opened up on the huge planes with automatic fire, burning one in the water and causing the second to crash on takeoff.

With those reinforcements, Kanemitsu and his men fought back. Japanese snipers in palm groves were hard to find, so Carlson pulled his men back to open terrain. The Japanese counterattacked three times in the afternoon, and another Japanese air raid hit the Raiders at about 4:30 pm.

By 5 pm, Carlson figured he had done enough damage and it was time to break off the action. He sent his boat crews back to the beach to get the boats ready for withdrawal. At 7 pm, Carlson ordered his main force to fall back with withdrawal to coincide with darkness and high tide. The withdrawal was difficult. The outboard motors did not work, and the Marines could not paddle their way over the breakers. Boats capsized, men lost their weapons, clothing, and gear, and were hurled up on the beach exhausted. Only seven boats and fewer than 100 men made it back to the submarines in the dark—45 to Nautilus and 25 to Argonaut. About 100 Raiders were still ashore, most of them unarmed—all machine guns and most rifles and automatic rifles had been lost.

Luckily for Carlson, the Japanese did not pursue the Americans, and that gave Carlson time to figure out his next move. He grouped his 120 or so men, four of them stretcher cases, on the beach. At midnight Carlson called a meeting of his officers and some of his men and asked what they should do—hide on the north end of the atoll? Try the surf again? Surrender? The Marines looked to their commander for a decision. He gave none. By his creed, all Marines could make their own choice. Sergeant Henry Herrero, Major Roosevelt’s runner, found five men willing to make another try for the submarines. They boarded a rubber boat and made it to Nautilus.

Meanwhile, Nautilus blinkered a signal to Carlson, saying the two submarines would stay as long as necessary to rescue the Marines.

During the night, there was only one skirmish with a Japanese patrol. At dawn Carlson made a new effort to get off the beach, sending Major Roosevelt through the surf with three boats and 15 men. They succeeded, but Carlson and about 70 Raiders were still on the hostile shore.

Nautilus sent back a volunteer five-man crew on a boat hoping to get a line through the surf and two of the remaining boats and the Leathernecks back to the sub. One of the five men made it ashore, but a Japanese plane strafed the boat and it disappeared into the brine.

With 70 men left, Carlson believed he had been abandoned and the only humanitarian thing to do now seemed to be to surrender. He wrote out such a note, handed it to a captain and a corporal, and ordered them to find the enemy. Instead, they found a native islander, who in turn found them a Japanese soldier, who took the note and then disappeared.

With no answer to the surrender offer, the captain and corporal set off to find the Japanese and discovered to their astonishment that there were no longer any Japanese troops on the island. Most of the defenders were dead, and the rest had fled to other atolls and islands.

Now master of all he surveyed, Carlson regrouped his forces and had them sweep the island from side to side. They found 83 Japanese bodies and two live Japanese stragglers, who they promptly shot, near the southern tip. The Raiders collected intelligence from the abandoned Japanese headquarters, destroyed supplies, including 700 barrels of aviation fuel, and finished off the radio station. The burning aviation gas was a fine navigational beacon for the submarines, and they headed for it to rescue the Raiders.

As dusk fell, the Marines carried four rubber boats to a quiet area of the lagoon, lashed them to an outrigger canoe, and entered the lagoon at 9:30 pm. By midnight all but 30 of the Raiders were back on the submarines. Twenty-one were dead, and nine were missing.

Actually those nine were still alive and on Makin. They avoided Japanese capture for a month, but when they were rounded up on August 20, they were flown to Japan’s 6th Base Force Headquarters on Kwajalein Atoll, where they were the problem of the force’s boss, Vice Admiral Koso Abe. The Japanese gave them candy and cigarettes, joked about the sights they would see in Tokyo, and put them in a barracks.

Meanwhile, Abe asked Tokyo what he should do with his nine captives. Tokyo did not tell him. He waited for six months, then made a flag decision ordering Kwajalein’s garrison commander, Captain Yoshio Obara, to execute the lot.

Obara, who had two brothers in America and nephews in the U.S. Army, protested vehemently against this illegal order, but Abe was adamant. He was also an admiral. Obara could not find any volunteer executioners, so he detailed four officers and selected October 16, 1942, the day that coincided with Japan’s annual memorial to departed heroes, the Yasukuni Shrine festival, as the day of execution.

That day the nine Marines were led to a large grave and ceremoniously beheaded in front of Abe. After the burial, Obara’s men placed flowers on the grave and considered the incident closed. But a Marshall Islands native witnessed the horror from a hiding place in the bushes.

After the war, Abe and Obara were tried on Guam for war crimes. Abe was hanged in 1946. Obara drew a 10-year sentence.

Meanwhile, Carlson and his merry band headed home. Nautilus reached Pearl Harbor on August 25, Argonaut a day later.

At a time when clear-cut American victories were few and far between, this one was a good boost for national morale. American newsmen shot photographs of the leathery Carlson and the skinny Roosevelt—he had overcome a stomach ailment to serve in the Marines—holding up a captured Japanese Rising Sun flag. The flag itself went through channels to Marine Corps Commandant Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb and from him to President Roosevelt in the White House, who put on a show of recoiling from the flag at a press conference to display it, refusing to touch the “evil banner.”

The flag wound up in the Marine Corps Museum. Roosevelt wound up receiving a Navy Cross, which helped cut down on Republican Congressional attacks on the four Roosevelt sons, all of whom while in uniform and on active duty were being accused of serving in cushy stateside jobs. In fact, all would see considerable combat by war’s end, and two of them, because of their Navy assignments in the Pacific, would miss their father’s funeral in April 1945.

Americans celebrated the raid as yet another tweak to the Japanese, like the Doolittle Raid and the defense of Wake, to make up for the defeats of Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, but military men on both sides took grim note of the bizarre encounter.

Carlson led his Raiders into action on Guadalcanal. In one 30-day, 150-mile armed reconnaissance, his men killed more than 500 Japanese at a cost to themselves of only 17 men. Illness sent Carlson home, and he never held another combat command, but was an observer at Tarawa and at Saipan. There he was injured while trying to rescue a wounded man, which led to his early retirement as a brigadier general in July 1946 and his equally early death the following year.

Roosevelt took over the new 4th Raider Battalion, while 2nd Battalion was sent to the Solomons, where it saw heavy fighting. Eventually all the Raider battalions became the re-formed 4th Marine Regiment in 1944, which took up the colors and heritage of the old “China Marines,” which had been annihilated in the defense of the Philippines, the only Marine regiment ever to surrender. By then all Marines were considered to be as tough and flexible as the Raiders, and there was no further need of specialized outfits in the mass amphibious assaults that were coming.

Nor had the raid succeeded in its original intent. The Japanese did not divert troops from Guadalcanal specifically to the Gilberts—there was no impact on the Solomons campaign. American officers regarded the military impact of the raid as being “negligible,” although it did provide the United States with some lessons on how to transport raiders by submarine to and from a defended target.

But, tragically, the Japanese did realize how weakly defended the Gilbert Islands were. A month after the raid, they landed a detachment of Special Naval Landing Forces on Tarawa, one of the Gilbert atolls. These troops, Japan’s version of America’s Marines, were ordered to prepare the island’s defenses, and prepare them they did. Tarawa alone received 24 coast defense guns ranging from 5.5-inch to 8-inch, some purportedly captured from the British defenses at Singapore, others incredibly from Russian defenses at Port Arthur, dating back to 1905 but still capable of hurling explosive shells at troops. Tarawa would also receive 25 field guns, a system of barricades, and bombproof shelters, all defended by 4,500 men. Makin itself would be defended by 800 men.

When the U.S. 2nd Marine Division stormed Tarawa’s defenses on November 19, 1943, they would pay an immense price for the success of the Makin raid—in 76 hours of bitter fighting they would suffer nearly 1,000 dead and more than 2,000 wounded.

Author David Lippman writes frequently for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in New Jersey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments