By Nathan N. Prefer

“Passchendaele with tree bursts” was how war correspondent Ernest Hemingway described it. The three-month slugfest that became known as the Battle the Hürtgen Forest was that and much more. It was one of the costliest and most frustrating battles fought by the U.S. Army in Europe during World War II.

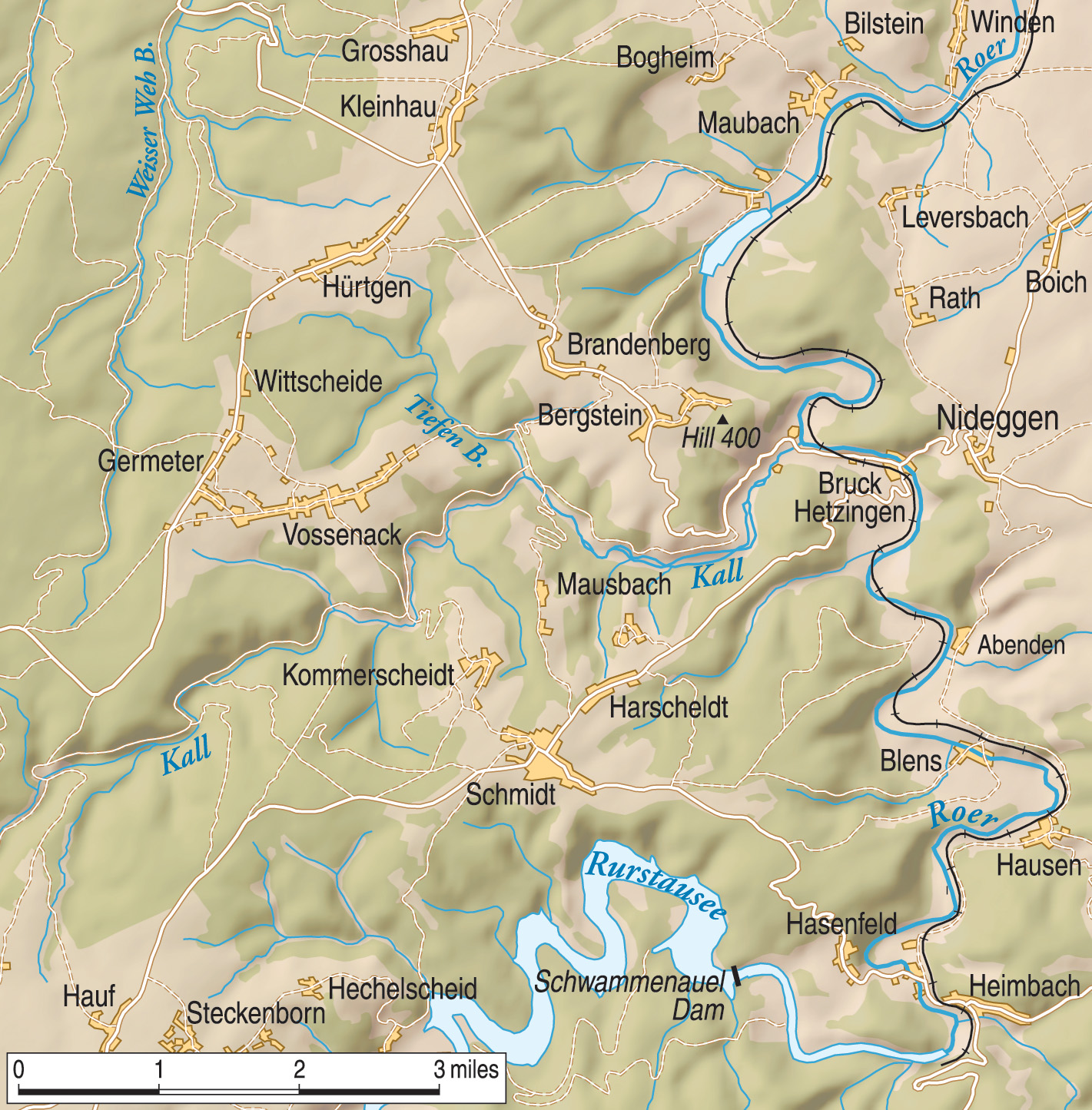

Before the war, there was no specific area known as the Hürtgen Forest. The wooded area that received that name on American maps was actually a plot of forested land 20 miles long and 10 miles wide that was the northernmost tip of the Ardennes region of Germany. A plateau of volcanic origin, it appeared to be a region of hills because of the many streams that have gouged their way through the area.

Roads were few and poor, and scattered villages within the forest provided the only shelter and road nets in the area. One such village was Hürtgen itself, from which the forest got its name. Another was Schmidt, which was the key to the entire three-month-long campaign.

The forest seemed to be taken straight from Gothic tales of frightening places. Until the 20th century, most travelers went around the forest, avoiding its dark and forbidding interior. The dark green fir trees, rising to heights of 75 to 100 feet, were thick and intertwined. Most days, the sun’s rays never penetrated to the floor of the forest, which was constantly wet, a result of all the streams flowing throughout the area and the lack of sun.

It was not until World War I that the Imperial German Army discovered that the forest could be used as a gateway into France. The French, knowing the difficulties of moving large military forces through such a dense wood, guarded it lightly. But the Germans, using the nearby Aachen Gap in the Ardennes, managed to push strong forces through the area to stunning effect. Some 25 years later, the forces of Nazi Germany repeated the feat, in both cases to France’s sorrow.

One of the most important watercourses through the forest is the Roer River. This river runs along the southern and eastern edge of the forest, past the town of Monschau, 16 miles south of Aachen. Beyond the Roer the land flattens out, leaving an open plain that leads directly to the Rhine River, Germany’s traditional natural barrier to the west. The Roer River was to become a significant factor in the Allied advance to Germany in 1944.

When the Allies reached the Aachen Gap, they had little fear of a major obstacle to their increasingly rapid advance to the German border. After a brutal struggle in northern France, they had broken out of the Normandy beachhead and surged across France, chasing after a defeated and demoralized German Army. Objective lines drawn up months before were taken and passed weeks—even months—earlier than originally planned. There seemed little in the way to slow down the Allied gallop across France and into Germany itself.

But that very confidence was already causing problems. The highly motorized Allied forces needed supplies to keep moving east. Those supplies had to come into a major port before they could be distributed. But as yet no such port had been seized. True, the ports of Cherbourg and Brest had been taken at considerable cost, but neither could accept the volume of supplies the Allies needed to keep moving. And the Allies kept moving farther and farther away from the ports, stretching the supply line to the breaking point.

The First Canadian Army had seized the city of Antwerp but had yet to clear the approaches to that major port. By September 1944, the Allied armies were having severe supply problems, needed more ground forces, and were about to face Germany’s major defensive line, known to them as the Siegfried Line.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, had decreed a broad-front policy. He had, in fact, allowed Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, commanding the 21st Army Group, to try a single powerful thrust to speed the Allied advance to Germany—a massive ground and airborne operation known as Operation Market Garden—but this had failed at Arnhem.

Eisenhower now returned to his broad-front strategy, which required that the Allied armies pierce the Siegfried Line, cross the Roer and Rhine Rivers, and enter Germany. Yet there were problems.

It was winter, and the rains and snows had produced significant runoff to the many streams and rivers in the area. The runoff, in turn, had filled the lakes behind the dams along the Roer River to near capacity. Those dams were in German hands and could easily be used to flood the area over which the American armies of General Omar N. Bradley’s 12th Army Group would have to pass.

Any Allied force that crossed the river before the dams were in American hands risked being isolated on the far bank by flooding and defeated in detail. Bradley, therefore, assigned the task of seizing the Roer River dams to the First U.S. Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges.

Hodges was 57 years old and a veteran of World War I, where he had earned a Distinguished Service Cross in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign. He, unlike most of his contemporaries, was not a graduate of West Point, having failed in his plebe year. Determined to make the military a career, he had enlisted and gained his commission from the ranks.

He later came to the attention of the U.S. Army’s Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, who monitored his career and placed him in command of the First U. S. Army. In September 1944, Hodges’ army had three corps with eight experienced combat divisions and three mechanized cavalry groups. The usual attached armor, tank destroyer, engineer, and artillery battalions were distributed among the combat units.

Having pierced the Siegfried Line in several places, First U.S. Army now had to move east into Germany. That required securing the Roer River dams and crossing the Roer and the Rhine. The only way to accomplish that, believed General Hodges, was to attack through the Hürtgen Forest. He understood that he could have bypassed the forest and found some way around to the dams, but both the supply issue and his lack of any reserve force raised the fear of a flank attack from the forest should he try to bypass it. So it would have to be a frontal attack. Maj. Gen. J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins’ VII Corps was assigned the task.

Sent first into the forest was the veteran 9th Infantry Division. Almost immediately the unique characteristics of fighting within the forest were realized. On the first day, the 60th Infantry Regiment had to fight to clear the supply route of the leading 47th Infantry Regiment. Then German counterattacks began. Concerned about the American attacks in the forest, General Erich Brandenberger, commanding the German Seventh Army, ordered more troops into the woods.

It soon became clear that the village of Schmidt, which sits atop one of the highest ridges west of the Roer and is only two miles from the Roer River dams, was a key objective. To get to Schmidt, an attacking American force would need to secure the Hürtgen-Kleinhau road net and the villages of Germeter and Vossenack. Once these were secured, a crossing of the Kall River would lead directly to Schmidt and the edge of the forest overlooking the dams.

With his first attack stalled by enemy defenses and counterattacks, General Collins ordered Maj. Gen. Louis A. Craig, commanding the 9th Infantry Division, to concentrate his full division for the next attack. But the 9th was thinly stretched, holding a nine-mile front. In order to gather just two of his three regiments for an attack, Craig had to leave his 47th Infantry behind and use the attached 298th Engineer (Combat) Battalion and 4th Cavalry Group to cover his front.

The 9th Division’s 39th and 60th Infantry Regiments would be facing a hastily thrown together grouping of miscellaneous German units under the umbrella command of the 275th and 353rd Infantry Divisions, part of Lt. Gen. Hans Schmidt’s LXXIV Corps.

The tired, understrength veterans and inexperienced replacements who fought the first battle for Schmidt were unaware that the German appreciation of them was far different than reality. German reports described the American infantrymen as “top-notch, rested, and well-equipped combat troops.” Apparently unknown to the Germans, American infantry companies were down to 80 men or fewer—less than half their authorized strength.

Fighting soon developed into a pattern. While artillery and mortars, or tanks and tank destroyers, fired to keep the Germans away from firing positions, small groups of six to eight American soldiers inched their way toward the enemy posts. When close enough, the firing would be stopped and the infantry charged the enemy, tossing grenades and firing hand weapons.

Charges of TNT were used to blow up pillboxes. Antitank weapons, such as the bazooka, fired rockets into stubborn holdout pillboxes or trenches. White phosphorus grenades also prompted surrender when dropped down the ventilation shafts. Rooting out the enemy remained a slow, costly, and painful process.

The battle was not one-sided. In the 39th Infantry Regiment sector one company had but two platoons left, one with 12 men and the other with 13. One entire company was lost to an ambush. Private James E. Mathews earned a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross by saving the life of his company commander at the cost of his own.

Yet, by October 15, the 9th Infantry Division had possession of the towns of Wittscheidt and Germeter. General Craig created forces from scratch by pulling individual companies, supply platoons, and others to add what he could to the attack. A tank company loaned from the 3rd Armored Division joined the battle.

Even as the 9th continued with its attack, events at higher headquarters changed the situation. Because Hodges wanted Collins’ VII Corps to move its main attack toward the Roer, he adjusted boundaries to give responsibility for the Hürtgen Forest, including Schmidt, to Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps. The 9th Infantry Division, which had cleared some 3,000 yards of the forest at a cost of more than one casualty per yard, would be relieved and sent to the rear for rest and replenishment. Its place in the forest would be taken by the 28th Infantry Division.

Major General Norman D. “Dutch” Cota’s 28th Infantry Division—known as the “Bloody Bucket”—was drawn from the Pennsylvania National Guard. It had come ashore in Normandy in July and fought at St. Lô before moving into northern France. It had some early difficulties, and its first commander, Lloyd Brown, was relieved of command, and the second, James E. Wharton, was killed by a sniper on August 12; Cota had commanded the division since that incident.

The division had paraded through Paris on August 29, 1944, before moving up into Belgium and then Germany. It had fought along the Siegfried Line near Grosskampenberg but had been halted by strong German resistance. After defeating heavy German counterattacks in the Wallendorf bridgehead area, the division returned to the Siegfried Line near Aachen before relieving the 9th Infantry Division in the Hürtgen Forest on October 25, 1944.

General Gerow directed Cota to launch a second attack on Schmidt. Largely because V Corps also had orders to support the VII Corps attack toward the Roer River, Gerow’s other divisions were unavailable. After reviewing the problem, however, he ordered Maj. Gen. Lunsford E. Oliver’s 5th Armored Division to assist the 28th by clearing the adjacent Monschau Corridor.

In effect, this was to be a double-pronged attack against the stubborn Siegfried Line positions that were delaying the V Corps’ advance. Here the importance of the Roer River dams was first made a part of the objective when the V Corps engineers warned that any advance over the river was subject to the status of the dams. But those dams were not an objective of either VII Corps or V Corps. First, however, Schmidt would need to be taken.

In addition to putting a combat command of Oliver’s division alongside the infantry, Gerow reinforced the 28th Division with what he had available. The 1171st Engineer Combat Group and the 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion were attached, as were the 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Towed), the 707th Tank Battalion, and the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (Self-Propelled).

While strengthening the division, Gerow then weakened its offensive power by ordering that one regiment secure the line of departure to guard against the kind of counterattacks that had slowed the 9th Infantry Division’s attack.

Gerow also ordered that a second regiment secure a road net leading into the Monschau Corridor, leaving only one infantry regiment to make the actual attack to seize Schmidt. By the time his division entered the forest, Dutch Cota felt that his division had only “a gambler’s chance of succeeding.”

The 28th had been fighting since Normandy. One of its acknowledged weaknesses was a lack of training for the steady stream of fresh replacements arriving from the United States. In one month, the division had absorbed 1,465 replacements—nearly all in the infantry. No training program, however realistic, can prepare a soldier for actual combat. These men had a difficult introduction into their new unit. Their initial reaction was “bewilderment, dismay, confusion, isolation.”

The time when these men needed moral support was when they joined their new unit. But the veterans were reluctant to offer support because they had already suffered enough seeing friends killed or wounded and did not want to expose themselves to more tragedies. Those replacements who survived became good soldiers with experience and were eventually accepted into the veteran community.

Cota selected the 112th Infantry as his assault regiment. It was to seize the village of Kommerscheidt and then Schmidt. Each village was just uphill of the last. The 112th also had to protect its own north flank by capturing Vossenack.

Supported by tanks of the 707th Tank Battalion, the attack began from Germeter into a heavy German artillery barrage on November 2, 1944. Using the church spire in Vossenack as a landmark, the infantry followed the tanks forward. The lead tank soon entered a minefield and a track was blown off. A second tank became mired in deep mud.

The tank company commander, Captain George S. West, Jr., came up and led the attack forward. In one infantry platoon that walked into a booby-trapped field, 12 men out of 27 were killed, others wounded. Platoon leaders fell as they led from the front. One machine-gun platoon was led by a corporal, all senior leaders having become casualties.

Nevertheless, the 112th Infantry gained its objective. They were soon digging in on Vossenack Ridge, preparing to fight off any counterattacks. Company F set up in the village with its command post in the last house on Vossenack’s main street.

Meanwhile, to the north the 109th Infantry Regiment had begun its attack to obtain a line of departure overlooking the village of Hürtgen itself. By early afternoon, the initial objectives had been reached and the regiment held a line along the Germeter-Hürtgen road. Stopped by a wide enemy minefield, the regiment halted for the night. South of the 112th Infantry, the 110th Infantry Regiment launched an attack to the southeast to knock out a group of pillboxes that would soon be known as the Raffelsbrand Strongpoint. Heavy resistance limited the gains made by the 110th Infantry on the first day.

Across the front lines senior German officers of Army Group B had been conducting a map exercise in which they anticipated an attack in the Hürtgen Forest on the boundary between the Fifth Panzer Army and the Seventh Army. Soon reports were received that exactly that type of attack was in progress.

The commander of Army Group B, Field Marshal Walter Model, immediately ordered a battle group of the 116th Panzer Division to counterattack against the advancing 109th Infantry Regiment. The rest of the division was to follow as soon as available. The attack was designed to clear the Vossenack Ridge of Americans and cut off the advance of the 112th Infantry Regiment.

Unaware of the coming counterattack, the 112th Infantry resumed its attack on November 3. Lt. Col. Albert C. Flood’s 3rd Battalion began the descent from Vossenack Ridge down the steep, wooded slope toward the Kall River. There was little opposition other than that of German artillery, and the Yanks soon reached and crossed the Kall; Kommerscheidt was in sight. Only a small group of the enemy opposed their advance.

Company K’s scouts were soon inside the village, followed by the rest of the company. Captain Eugene W. O’Malley, Company K’s commander, could see Schmidt from the edge of Kommerscheidt and was in the process of organizing an attack on Schmidt when suddenly a short but intense artillery barrage hit Kommerscheidt.

Undeterred, O’Malley waited out the barrage and then started his company for Schmidt. Enemy opposition remained slight. The lead elements of Company K reached the outskirts of Schmidt, and O’Malley split his force, sending half into Schmidt and the other to a small sector of the town along the Schmidt-Strauch road.

Enemy resistance in Schmidt was minimal; many Germans had been eating and several were drunk, and the town was soon secured. Company K, 112th Infantry had secured the division’s objective in less than two days of fighting.

Nearby, Captain Jack W. Walker’s Company L had advanced alongside, also against minimal opposition. It entered Schmidt, taking 30 enemy prisoners, shortly before darkness fell. By nightfall only a few houses along the Hasenfeld road offered sniper and machine-gun opposition.

Soon thereafter, the reserve company, Company I, also entered Schmidt followed by Captain Guy T. Piercey’s heavy weapons Company M. But the closest American tanks could get to Schmidt was 1,500 yards because of unsuitable terrain and minefields. Behind them Major Robert T. Hazlett’s 1st Battalion, 112th Infantry moved into Kommerscheidt; the 2nd Battalion remained in Vossenack. The situation was looking good.

With night covering everything, the mopping-up operations in Schmidt came to a halt as the 3rd Battalion, 112th Infantry dug in for the night. Sniper fire continued to harass the battalion, and Company L was still receiving machine-gun fire from the houses along the Hasenfeld road. Nevertheless, the night was relatively quiet and the soldiers felt satisfied that they had achieved their objective with relative ease. Stray Germans, unaware that Schmidt was now in American hands, wandered into the American perimeter during the night.

To the northwest, the 109th Infantry had been about to launch its attack to seize Hürtgen when it was struck by two counterattacks, each numbering about 200 enemy troops. Although both attacks were beaten off, the American attack was delayed.

To the south, the 110th Infantry also made little progress against the Raffelsbrand Strongpoint. General Cota authorized releasing the regiment’s 1st Battalion, which had been the division reserve, for a new attack on November 4.

Across the lines the German commanders, meeting at the Schlenderhan Castle west of Cologne, decided to bring up the entire 116th Panzer Division for a counterattack that would push the Americans back.

From the German viewpoint, holding the Hürtgen Forest was necessary for two reasons. First, it protected the flank of the coming major counteroffensive—soon to be known in the West as the Battle of the Bulge. Second, a battle in the forest would protect the Siegfried Line defenses and the Roer River dams, as well as being easier than fighting in the open with the depleted forces available to the Germans.

The next day, November 4, the Germans struck in force. After a heavy artillery barrage on Schmidt, German infantry with tank support attacked from the southeast. The panzers quickly got into the village and began to knock out the American defenses. With only a few antitank weapons available, the Americans were soon overwhelmed.

Then another battalion of the 1055th Infantry Regiment struck from the west. The two-pronged attack routed the Americans. With no adequate antitank defense, the battle quickly went against them. About 100 men were cut off in Schmidt and either killed or captured—the rest withdrew. Without tank support and with their flanks left open because of the inability of their sister regiments to close up, the 3rd Battalion, 112th Infantry was left with no options.

As the Schmidt survivors reached Kommerscheidt, the men of the 1st Battalion grabbed them and placed them in defensive positions—positions that were surrounded by dense woods on three sides. Only three tanks from the 707th Tank Battalion were available. The battalion’s call for more tanks brought instead the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. George A. Davis, and the regimental commander, Colonel Carl L. Peterson.

Before they could reach Kommerscheidt, however, the Germans launched their next attack out of Schmidt with five tanks and a battalion of infantry. The panzers stayed just beyond the range of the American bazookas and pounded the town at will. Friendly artillery failed to discourage the German tanks. More enemy tanks opened fire from other directions. The three 707th Tank Battalion tanks moved forward and opened fire. They claimed three panzers knocked out while others were hit by supporting fighter bombers of the 397th Squadron, 368th Fighter Group.

At this point Colonel Peterson arrived and assisted in the defense, organizing stragglers and leading them back into the fight. General Davis reviewed the situation along with Peterson and the battalion commanders and radioed a situation report back to Cota. Captain Marion C. Pugh’s Company C, 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion was ordered up to the town, but the blocked supply route halted their efforts.

Finally, nightfall brought an end to the day’s battle. An order from division headquarters to attack and retake Schmidt was ignored. The 112th Infantry would have all it could do just to hold Kommerscheidt.

The Germans had brought up reserves to continue their attacks. In addition to the 116th Panzer Division, major elements of the 89th Infantry Division provided additional infantry for the attack; elements of the 347th Infantry Division also took part. The 272nd Volksgrenadier Division also contributed battalions as it arrived in the area. Seventh Army sent several additional artillery, assault gun, antitank, and mortar battalions to reinforce the attack.

Dawn on November 5 brought another German attack. With supporting artillery and the tanks of the 707th Tank Battalion in Kommerscheidt, the morning’s attack was beaten off. By mid-day, two platoons of Company C, 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion had managed to squeeze up the supply trail and reach Kommerscheidt.

Another attack hit the town just as General Cota ordered a renewal of the attack to take Schmidt. Once again, Colonel Peterson had no choice but to ignore the order. Undeterred, Cota formed Task Force Ripple, led by Lt. Col. Richard W. Ripple, commander of the 707th Tank Battalion. Leading the 3rd Battalion, 110th Infantry and two of his own tank companies, with tank destroyers from Kommerscheidt, Ripple was ordered not to reinforce Kommerscheidt but to pass through it and seize Schmidt.

Meanwhile, along the Vossenack Ridge, the 2nd Battalion, 112th Infantry had spent three days and four nights under constant enemy shelling. Reinforced with a platoon of Company C, 707th Tank Battalion and a platoon of Company B, 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion, they anxiously awaited the inevitable enemy attack.

Instead, November 6 dawned with complete silence. Some men in outlying foxholes began to panic and started to withdraw into the town. Then, suddenly, strong German artillery and small-arms fire began to hit the American positions. Rumors that the Germans were attacking spread panic among the infantrymen. As each company retreated, the next company was pulled into the maelstrom. Officers who retained control of their units soon had no choice but to withdraw as well rather than be left stranded and without support. Vossenack was soon abandoned.

Meanwhile, Task Force Ripple fought its way along the supply trail against enemy infiltrators. Lt. Col. William Tait’s 3rd Battalion, 110th Infantry lost 17 men in these engagements.

But in Kommerscheidt the sounds of the battle going on behind them convinced many of the Yanks that they were surrounded. Enemy observation from Schmidt increased the accuracy of the German shelling. The arrival of Task Force Ripple late in the day prevented any attack against Schmidt from being launched on Kommerscheidt.

But at Vossenack, General Davis ordered a new defense line just south of the town and strengthened it with tanks from the 707th Tank Battalion and all of Company B, 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion. Companies of the 1171st Engineer Combat Group were also alerted for duty as riflemen.

The 109th Infantry Regiment attempted to renew its attack on November 7 but made no progress. That same day came word that they would be relieved by the 12th Infantry Regiment of Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton’s 4th Infantry Division. Meanwhile, at Kommerscheidt the Germans attacked again, getting a panzer into the town and another so close that it rolled up to Colonel Ripple’s command post dugout.

As the Germans continued to move into the town, more and more Americans left their positions and pulled back. Colonel Peterson called up his sole remaining reserve, Company C, 112th Infantry. At this time, Peterson, at his CP in Kommerscheidt, received a message recalling him to division headquarters. The message gave no reason and only ordered him to report immediately. Although he was aware of a rumor that he was about to be relieved of command, he left the town and started back.

In town, with German tanks roaming the streets at will, the 112th Infantry survivors were left with no recourse but to abandon the village. Colonel Ripple and other officers managed to establish a weak defense in a wooded line north of the village.

Colonel Peterson’s trip to division headquarters was a nightmare. With two enlisted men, he started out along the supply trail. Almost immediately they had to abandon their jeep when enemy machine-gun fire blocked the trail. Moving back, they came across several ambushed parties and helped move the casualties from the supply trail. Blocked again by small-arms fire, they took to the woods with enemy mortar fire following them.

A brief firefight with a party of Germans brought down more mortar fire on the group, and Peterson was wounded in his left leg. One enlisted man went ahead for help while the colonel and the remaining man struggled forward.

As they moved, they were again ambushed by a German patrol and Pfc. Gus Seiler, the enlisted man, was killed. Enemy mortar fire again wounded Colonel Peterson in the left leg. He dragged himself back over the Kall River where three Germans approached him. Firing at them, Peterson drove them off. He crossed the river yet again, crawling through the muddy woods until finally he heard American voices. After yet more crawling and river crossings, he was finally rescued by a two-man patrol. Colonel Gustav M. Nelson of the 5th Armored Division assumed command of the 112th Infantry later that day.

The 28th Infantry Division did not capture Schmidt. Despite the attachments of the 12th Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Ranger Battalion, no advance could be accomplished.

The 112th Infantry Regiment suffered 232 men captured, 431 missing, 719 wounded, 167 killed, and 544 nonbattle casualties, mostly trench foot, illness, and combat fatigue.

The 707th Tank Battalion lost 31 of its 50 medium tanks, while the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion lost 16 of 24 vehicles. In total, the 28th Infantry Division, not including attached units, lost 6,184 men during the November battles in the Hürtgen Forest.

Major General Donald A. Stroh’s 8th Infantry Division, which had been resting in a quiet sector along the Our River, moved up on November 19 and took over the exhausted 28th’s positions. It was the first rest the 8th had had for quite some time. After landing in France, the 8th had fought in Normandy, Brittany, and along the Siegfried Line before entering the Hürtgen Forest. Now it was time for a new test.

The division planned to attack through the 4th Division’s 12th Infantry Regiment using its 121st Infantry Regiment. They were to be supported by the 12th Engineer (Combat) Battalion and Combat Command R of the 5th Armored Division. Units of the 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion and 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion were also attached. The attack began on November 21.

Enemy artillery, mortars, and mines slowed the attack considerably, and casualties grew numerous. Three times the regiment attacked in one day, each time achieving only limited gains. The 709th Tank Battalion’s tanks made little difference, and the Hürtgen Forest ruined the career of yet another regimental commander.

Two battalion commanders fell to wounds or sickness. A third was relieved of command. The division’s chief of staff took command of the 121st Regiment personally. Another major attack on November 24 fared no better.

Off to the east, Barton’s 4th Infantry Division was making some progress, but increased German reinforcements slowed all attacks. To strike before more German reinforcements arrived, 5th Armored’s Combat Command R was committed with General Hodges’ approval. Despite a heavy smoke screen and artillery preparation, the tanks were halted before they got far. Four destroyed Shermans blocked the only access into the village of Hürtgen.

Still, the 4th and 8th Infantry Divisions continued with the attack. On November 26, the 121st Infantry actually put a small patrol into Hürtgen, and Company F moved to within 300 yards of the village before being stopped by enemy fire.

The next day saw greater progress. Lt. Col. Roy Hogan’s 3rd Battalion, 121st Infantry, aided by 709th Tank Battalion Shermans, reached the southern edge of Hürtgen. On the opposite side, the 1st Battalion, 13th Infantry approached the northeast side of the village. Then came startling news—the regiments reported the town abandoned.

Unfortunately, as the men of the 13th and 121st Infantry Regiments soon found out, the report of a German withdrawal from Hürtgen was unfounded. In the morning, elements of the 13th Regiment and the 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion set up defensive positions on the Kleinhau-Brandenberg road. Nevertheless, the 121st Infantry had to fight its way into the village proper and met with success; 350 prisoners were taken. Combat Command R was alerted to prepare to attack Kleinhau, supported by the 28th and 121st Infantry Regiments.

Kleinhau fell to Combat Command R on November 29. Remaining enemy pockets were cleaned out by the 13th and 121st Infantry Regiments. A renewal of the attack on November 30 saw the 8th Division’s 28th Infantry Regiment reaching Vossenack. But the next day strong enemy counterattacks turned the 8th Division onto the defensive.

Once again, the 1171st Engineer Combat Group was alerted to act as infantry, and the 2nd Ranger Battalion was trucked forward as a reserve. Brig. Gen. William G. Weaver, newly assigned commander of the 8th Division, ordered his division back into the attack; Brandenburg fell to the 28th Infantry Division and Combat Command A of the 5th Armored Division.

To the north, the 4th Infantry Division, exhausted and severely understrength, was relieved by the 83rd Infantry Division. The “Ivy” Division retired to a quiet area along the Our River for some R&R, but both it and the 28th Infantry Division would soon find themselves fighting for their lives against the massive German winter offensive out of the Ardennes Forest.

The Germans wanted Bergstein back. Three times they attacked the 3rd Battalion, 28th Infantry, being supported by Combat Command R. Most of the German 980th Infantry Regiment attacked without success. For its gallant stand at Bergstein the 3rd Battalion, 28th Infantry Regiment, 8th Infantry Division,was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation.

Other Presidential Unit Citations, one for the 1st Battalion, 13th Infantry Regiment and one for the entire 121st Infantry Regiment, were also earned in the fighting within the Hürtgen Forest. The 22nd Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division received the same honor, attesting to the fierceness of the fighting in the forest.

There were individual awards as well. The 4th Infantry Division faced what the infantrymen called “The Thing.” This was a pyramid of three concertinas of wire 10 feet high supported by rows of railroad ties embedded in the ground. First Lt. Bernard J. Ray, a 23-year-old platoon leader in Company F, 8th Infantry Regiment, from Baldwin, New York, was sent to knock it out. The Yanks could not bypass it, for the road had to be cleared for tanks, without which the infantry could not advance.

Even though his platoon sergeant told him he was crazy, Lieutenant Ray loaded himself up with grenades, percussion caps, and a 20-foot length of primer cord wrapped around his waist. His plan was to crawl out and blow up “The Thing.” Crawling forward under heavy German fire, Ray miraculously reached the obstacle unhurt and set about planting his explosives.

As he did so, he had to get up on his knees and was immediately struck by enemy mortar fragments. Seriously wounded, he managed to complete the preparation and then, clearly knowing what he was doing, pushed the plunger down. “The Thing” and Lieutenant Ray were gone. The 8th Infantry Regiment moved on. For his actions, Lieutenant Ray received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Ray’s commanding officer was Lt. Col. George L. Mabry from South Carolina, a veteran of the Utah Beach D-Day landings. Commanding the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, he found his men stalled by a minefield and heavy German resistance on November 20. Knowing that he needed to set an example, Mabry went to the front and personally cleared a path through the mines. He then moved ahead of the lead scouts until faced with a barbed-wire obstacle. This he destroyed with explosives and wire cutters.

Then he personally led his three rifle companies forward. Leading the men through the thick forest, he came upon and captured three enemy soldiers. Moments later he charged up a hill against three German bunkers and engaged the occupants in hand-to-hand combat. He immobilized two of these before his men raced up and captured the remainder. He then attacked a third bunker and knocked it out with small-arms fire.

Inspired by his courage, Mabry’s battalion surged through the forest, captured its objective, and held it against repeated counterattacks. For his leadership and personal courage, Colonel Mabry received the Medal of Honor.

At the nearby town of Bergel, the Germans launched a strong attack led by a heavy tank against the 329th Infantry Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division on December 14. In their way stood an Iowa farm boy named Ralph G. Neppel. With most of the regiment concentrated in the town and unprepared for the attack, the Germans were about to overrun the regiment when Sergeant Neppel intervened.

From his machine-gun position the sergeant opened fire on the advancing Germans. Many fell to his fire while the others scattered. His supporting riflemen kept the Germans pinned down, but the tank rolled to within 30 yards of Neppel’s machine gun and blasted away with its cannon.

Sergeant Neppel later said he barely remembered the tank firing: “There was a tremendous roar, a blinding flash. The next thing I knew I was lying 10 yards behind my gun. My gun crew was sprawled all over the road.”

Sergeant Neppel, minus his right leg and with his left leg smashed, painfully pulled himself back to his gun on his elbows and resumed firing. The Germans, expecting that opposition had been eliminated, were surprised and caught out in the open. Every one of them fell to the sergeant’s fire. The panzer, without infantry support, retreated. Sergeant Neppel would spend nine months in the hospital and learn how to walk again with his prosthesis before he was summoned to the White House to receive his Medal of Honor.

Two days after Sergeant Neppel’s gallant stand at Bergel, all offensive action in the Hürtgen Forest came to an end. The huge German counteroffensive, known later as the Battle of the Bulge, began to the south, and most Allied resources were directed there.

Schmidt would not fall in 1944. In fact, it did not fall until February 1945, when Maj. Gen. Edwin P. Parker, Jr.’s 78th Infantry (“Lightning”) Division took it.

Once again, the V corps, now under the command of Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner, former commander of the 1st Infantry Division, was the attacking force. General Parker’s division had joined the front lines in November, and one of its regiments, the 311th Infantry, had been attached to the 8th Infantry Division during that units’ fight in the Hürtgen Forest in November. Since then, they had been guarding the Monschau Corridor on the northern flank of the Ardennes penetration into American lines.

Under the Ninth Army of Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, the Lightning Division had prepared defenses and was ready to advance once the enemy counteroffensive was defeated. That time came early in February 1945.

The division occupied a two-mile-deep salient into the Siegfried Line on the German border between Aachen and St. Vith, Belgium. Since November they had been facing the same enemy, the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division. Under General Simpson the 78th Infantry Division had begun a series of limited-objective attacks to place it on the north bank of the Roer River. On November 2, it was transferred to the V Corps, First Army, and ordered to continue the attack. The objectives now were Schmidt and the Schwammenauel Dam. Until the dam was secured, Ninth Army could not cross the Roer.

Following the crest of the Schmidt Ridge and a small trail north of the Kall River, the 78th’s advance succeeded in reaching the town on February 7. The German defensive position was weakly manned. When obstacles barred the way, General Parker ordered Colonel Thomas H. Hayes’ 310th Infantry Regiment to go cross-country to the objectives.

Small firefights occurred as the regiment moved forward, but none were determined enough to stop the 310th’s advance al-though, when Company A was ambushed, the unit was erroneously reported as “cut to pieces.”

The advance of the 311th Infantry received less opposition. Crossing difficult terrain, climbing through woods and ravines, the infantry pushed forward. Facing strong forces, and with no reserves, the 272nd Volksgrenadiers fell back slowly. Soon the Americans, some riding the tanks of the 744th Tank Battalion, were moving steadily up the ridge.

By the morning of February 7, the 3rd Battalion, 311th Infantry was at the outskirts of Schmidt. Enemy artillery fire knocked out a tank, so Company I advanced without the armor. Firing as they moved, they entered the northern sector of Schmidt. German resistance was strong, but Company I advanced.

Company K approached Schmidt from the south, firing their machine guns from the hip to suppress enemy fire. They walked into a minefield but pressed on, forcing the enemy to slowly give ground. The two assault companies then cleared the town in house-to-house fighting. The shattered town was soon in American hands.

After more than three months of furious fighting in the green hell of the Hürtgen—and the attempts of five American combat divisions and an armored combat command—the tiny hamlet of Schmidt had finally fallen; the Lightning Division went on to secure the dams to prevent their destruction by the enemy.

The danger was past. The Americans soon crossed the Roer River and began their race to the Rhine. In three more months, Nazi Germany would surrender. But the surviving veterans would always remember the hell of the Hürtgen and the brutal fight for Schmidt.

Really great tribute to a forgotten battle. Thank you!