By David A. Norris

Captain Daniel Lienard de Beaujeu rushed to save the remote French outpost of Fort Duquesne in early July 1755. Weeks away from receiving substantial reinforcements, the fort was the target of British Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock. With Braddock was the largest army in the North American frontier, and enough mortars and 8-inch howitzers to smash the French defenses. On July 9, 1755, Beaujeu led most of the garrison’s regulars, Canadian militia, and Indians in a last-ditch attempt to ambush the British at a vulnerable point, where they had to ford the Monongahela River.

Seven miles from the fort, at the edge of a little ravine carved through the forest by a small creek, Beaujeu saw he was too late. Braddock’s vanguard was well beyond the ford and just across the creek. Soldiers in the service of Great Britain and France spotted each other at the same instant. Shots echoed through the Pennsylvania forest lands claimed by monarchs in faraway Paris and London.

While English colonists settled along the Atlantic coast in the mid-18th century, France held loose sway across the vast interior of North America, around the Great Lakes, and along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Fur trading, with the cooperation of a network of Indian tribes, brought great wealth to France. By the 1740s, English fur traders had reached the Ohio River country west of the Appalachians. Alarmed by the development, the colonial administrators of New France tightened their hold on the Ohio Valley. A new governor, Michel-Ange Du Quesne de Menneville, known as the Marquis de Duquesne, arrived in 1752. Fort Niagara already provided a key French foothold where the Niagara River emptied into Lake Ontario. Duquesne soon built new posts at Forts Presque’ Isle, Le Boeuf, and Machault in western Pennsylvania.

At the time, Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie was serving as the de facto chief executive of Virginia on behalf of Governor Willem Anne van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle, who chose to remain in England. Virginia’s rulers considered the Ohio River country as part of their colony. Many prominent men, such as Dinwiddie, were heavily invested in the Ohio Company, which sought to profit by filling the Ohio Valley with Anglo-American settlers. Reports of French trespassers on what he regarded as Virginian soil spurred Dinwiddie to action.

Dinwiddie loathed the French. As they pushed south from Canada, he feared that they would soon encroach on Virginia. “The French are like so many locusts,” he wrote. “They are collected in bodies in a most surprising manner; their number now on the Ohio is from twelve hundred to fifteen hundred.” His estimate of French forces was intended to provoke the British Crown into prompt action.

On October 31, 1753, Dinwiddie ordered a small expedition to the headwaters of the Ohio River to warn away the French. Leading the expedition was a 21-year-old militia major named George Washington. The French, though, brushed off his demands to leave.

Another party sent by Dinwiddie halted where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River. They began building a fort until a larger French force appeared and drove them away. The French, who continued building, named their new post Fort Duquesne. By holding the headwaters of the Ohio, France gained tenuous control of a 2,000-mile water route down the Ohio to the Mississippi River, which flowed to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico.

In the spring of 1754 Colonel Joshua Fry and newly promoted Lt. Col. Washington led 300 Virginia militia north to hold and expand the British fort being constructed at the Forks of the Ohio. They soon met the Virginians the French had expelled from the fort. Captain Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur, commander of Fort Duquesne, sent Ensign Joseph Coloun de Villers de Jumonville for a parley with Washington on May 28. Seeing Jumonville’s party as an attacking force, Washington ambushed the French in what became known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen. Ensign Jumonville and approximately 10 of his men were killed, and nearly all the rest were captured. Only one French soldier escaped to bring news of the clash to Fort Duquesne.

Washington withdrew to a place known as Great Meadows and built a log stockade called Fort Necessity. Acting on rumors that a large British army was marching to join Washington, Contrecoeur sent 700 men under Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers (Jumonville’s brother) to take Fort Necessity. After a day of fighting, the fort surrendered on July 4, 1754. Washington and the garrison were allowed to leave, but the French burned down the stockade.

Although Britain and France were not yet officially at war, London agreed late in 1754 to Dinwiddie’s pleas for ordnance, ammunition, and two regiments of regular infantry to drive the French out of Fort Duquesne.

To command the Fort Duquesne expedition, Captain General William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, chose Braddock. Born in Scotland, Braddock was the son of another major general of the same name. In 1710, the younger Braddock joined his father’s regiment, the Coldstream Guards, as an ensign. Braddock was well known in London society for his aggressive and bullying manner, and he had fought at least one duel with a higher ranking officer. Braddock served competently in Holland under Cumberland’s eye during the War of the Austrian Succession. The duke believed Braddock was the best choice not only to command the expedition into the Ohio Country, but also to serve as the commander in chief of all British regular forces in North America.

Braddock was both an able administrator and strict disciplinarian. While he was regarded as a brave commander, he was not a gifted tactician by any means. In the North American campaign that loomed before him, his loyalty to his superiors and his rigidity would blind him to much of the sound advice offered by colonial governors.

With a promotion from colonel to major general, Braddock landed at Hampton Roads, Virginia on February 19, 1755. His command consisted of two regiments of regulars, the 44th and 48th Foot. Lieutenant Robert Orme, an officer Braddock knew from the Coldstream Guards, accompanied the general as his aide. William Shirley, son of the governor of Massachusetts, served as Braddock’s secretary.

Washington expressly declined the opportunity to command Virginia militia on the expedition so that he could join Braddock as a volunteer. Doing so entailed serving without pay in a junior officer’s capacity for a chance to be commissioned in the field or obtain his commander’s patronage. Because of his intimate knowledge of the Ohio Country, on May 10 Braddock appointed Washington to serve as an aide-de-camp on his staff.

Braddock’s ambitious plan carried forward the military strategy previously envisioned by Cumberland. He would send one army against French forces in New Brunswick, another army against French forces around Lake Champlain, and yet another against French forces at Fort Niagara. The fourth army, which Braddock would lead himself, would march on Fort Duquesne. Once these points fell, Braddock would unite his forces and capture Quebec and Montreal, driving the enemy from New France altogether.

From the outset, the Braddock expedition got off on the wrong foot. The quickest way to get the soldiers to Fort Duquesne would have been to land them at Philadelphia; instead, the British squandered a great deal of time by landing them in southeastern Virginia and marching northwest across the Potomac River toward Fort Duquesne. Although the colonial government in Pennsylvania was heavily influenced by pacifist Quakers and largely indifferent to the needs of the army, there was sufficient equipment on hand to support Braddock’s expedition.

Philadelphia printer Benjamin Franklin interceded on behalf of the expedition. He composed two broadsides, which were widely distributed and read, and he also made direct appeals to friends and acquaintances in the back country. As a result of his efforts, Pennsylvanians sent wagons, draft animals, and supplies south to join Braddock’s army en route to its objective.

Braddock’s regular regiments were chronically understrength after languishing on garrison duty in Ireland for several years. To fill their depleted ranks, the British army transferred soldiers from other units. In addition, the army authorized further recruitment for the units in the American colonies. The goal was to ensure that each regiment had 700 men. The hurried recruitment effort resulted in a high proportion of untrained men devoid of combat experience.

Fort Cumberland, a log stockade at the confluence of Will’s Creek and the Potomac River on the Maryland frontier, became the staging point for the advance on Fort Duquesne. The Pennsylvanians responding to Franklin’s appeal sent 150 wagons and teams and 500 packhorses to join the expedition at that location. One train of pack animals from Philadelphia bore an array of supplies intended as gifts for the junior officers of the two British regiments.

During the army’s time at Fort Cumberland, it was necessary to turn the horses loose in the forest “to feed on leaves or the young shoots of trees,” wrote Orme. Many of the horses were lost or stolen, and the lack of suitable forage weakened the rest.

Braddock’s army departed Fort Cumberland on June 10. The army comprised 1,400 regulars evenly divided between the 44th and 48th Foot, 300 provincial troops, and 100 British artillerymen. The provincial troops hailed from Virginia, New York, Maryland, North Carolina, and South Carolina. In addition, there were civilian drovers, servants, and camp followers, including women and children. Some British officers brought their batmen, and some of the American officers brought their slaves as valets. Braddock also had 30 sailors of the Royal Navy who accompanied the expedition because of their expertise handling block and tackle, a mechanical system necessary to secure the expedition’s heavy wagons as they traveled up or down steep mountain grades.

Efforts to add a substantial force of Indian allies familiar with the back country failed miserably. Pennsylvania trader George Croghan, who had cultivated good relations with the Indians of the Ohio Country during the course of his career, rounded up Mingos who lived near his trading post north of Fort Cumberland, and also dispatched a messenger to the Ohio Country with an invitation for Delawares, Mingos, Oneidas, and Shawnees to come to the fort to meet with Braddock.

Braddock regarded the Indians with great disdain. He not only believed that Indians posed no threat to his regulars, but also that they would not benefit him as allies in a fight. The Indians, who wanted the French out of the Ohio Country, were inclined to work with the British. The most distinguished were Scarouady, who was half-king of the Iroquois in the Ohio Valley, and Shingas, the principal war chief of the Delawares.

Shingas asked Braddock what the English intended to do in regard to the back country once they had driven out the French. “The English should inhabit the land and inherit the land,” replied Braddock, adding “No savage should inherit the land.” The Indian leaders posed the same question to Braddock the following day in hopes of receiving a more palatable reply. During the ensuing discussion they told him that if they were going to shed their blood for the land, then they must be allowed to live freely upon it. Braddock told them in no uncertain terms that he did not need their help in expelling the French from the region. It was a deeply offensive answer and had the immediate effect of alienating the Indians attending the meeting.

All but Scarouady and seven Mingos returned home. When Shingas and the other members of the delegation returned to Ohio Country, they informed the members of their various tribes of Braddock’s response. Not surprisingly, some of the Indians departed immediately to ally themselves with the French.

Among the British and colonial soldiers in the expedition were several men destined for fame two decades later in the American Revolution. Besides Washington, Braddock had the services of wagoners Daniel Boone and Daniel Morgan, as well as New York militia officer Horatio Gates. Braddock’s subordinate commanders were Lt. Col. Thomas Gage, who would command the British forces in North America in 1775, and Lieutenant Charles Lee, who would become a general in the Continental Army.

Axe-wielding soldiers hacked a 12-foot-wide road through the forest for the wagons and guns. Soldiers toiling on the road received extra pay. The extra pay amounted to six pence a day for privates, nine pence for corporals, and a shilling for sergeants. On June 25 the men were offered a further reward of five pounds for each Indian scalp. Braddock worried that the extra pay would diminish his available funds; since there was nowhere for the men to spend their extra pay, he ordered it withheld until the next winter’s lull. Many of the men would not live to receive their bonus pay.

Up to that point, colonial forces had fought most of the Indian wars in North America. For that reason, the British Army had relatively little experience against the Indians who inhabited the forests of North America. Braddock’s troops plodded west over a dense, damp, and shady forest floor hardly touched by the light of the sun. In the gloomy desolation, the provincials told chilling tales about Indian warfare. The provincial soldiers and backwoodsmen warned the increasingly nervous regulars that fighting the Indians with European tactics would get them all slaughtered.

The French also had been taking steps to strengthen their position in the upper Ohio Valley. During the previous winter, Contrecoeur had asked Duquesne to relieve him from command of Fort Duquesne. His replacement, Montreal-born Captain Liernard de Beaujeu, was one of the most capable French officers on the frontier. Like other French-Canadian officers, he was willing to adopt Indian and frontier ways in warfare. During the 500-mile trip from Montreal, Beaujeu spent much time securing the French supply line and forwarding weapons and food to Fort Duquesne. He joined Contrecouer late in June.

Following its departure from Fort Cumberland, the British column made agonizingly slow progress through the wilderness. Cutting the road slowed the column to only a few miles a day. Eight days of hard labor found the expedition only as far as Little Meadows, 30 miles from Fort Cumberland. Washington fretted that French reinforcements were on their way to Fort Duquesne. For that reason, he recommended that they divide the army into a so-called flying column that would press ahead as quickly as possible toward the objective, while a supply column that constituted the baggage train with its cumbersome wagons followed in its path.

Braddock consented and took two thirds of his men with him on June 18. The remainder, under command of Colonel Thomas Dunbar, would follow as best they could. Braddock retained four 12-pounders, four 8-inch howitzers, a pair of 6-pounders, and three Coehorn mortars. Thirty wagons and 400 pack horses carried supplies. The flying column also had 100 spare horses. Drovers brought along a herd of cattle and some sheep for fresh meat.

Washington was disappointed that they still made slow progress. The regulars continued “halting to level every Mold Hill, and to erect Bridges over every Brook,” he wrote. “We were 4 days getting 12 miles.”

On June 24, just before reaching the Great Meadows, the marchers found a recently abandoned Indian camp. The Indians had “stripped and painted many of the trees, upon which they and the French had written many threats and bravados with all kinds of scurrilous language,” wrote Orme. The following morning, the enemy killed and scalped three men who had wandered beyond the picket lines. Two days later, Orme noted a more chilling display at another empty Indian camp. “They had marked in triumph upon trees, the scalps they had taken two days before, and a great many French had also written on them their names and many insolent expressions,” wrote Orme.

The French and their Indian allies launched small-scale attacks on Braddock’s column as it continued west. Washington wrote on June 28 that there had been “frequent alarms, and several men have been scalped, but this is done with no other design than retard the march.” Although there was not enough of the enemy to make a major assault, the alarms put everyone on edge.

On July 3 Braddock held a council of war. The officers who attended the meeting debated whether to halt until Dunbar caught up to them. Once the two columns had reunited, they could resume their march confident that they were employing their full strength. In the end, though, the council decided it could not afford the delay and resumed the march.

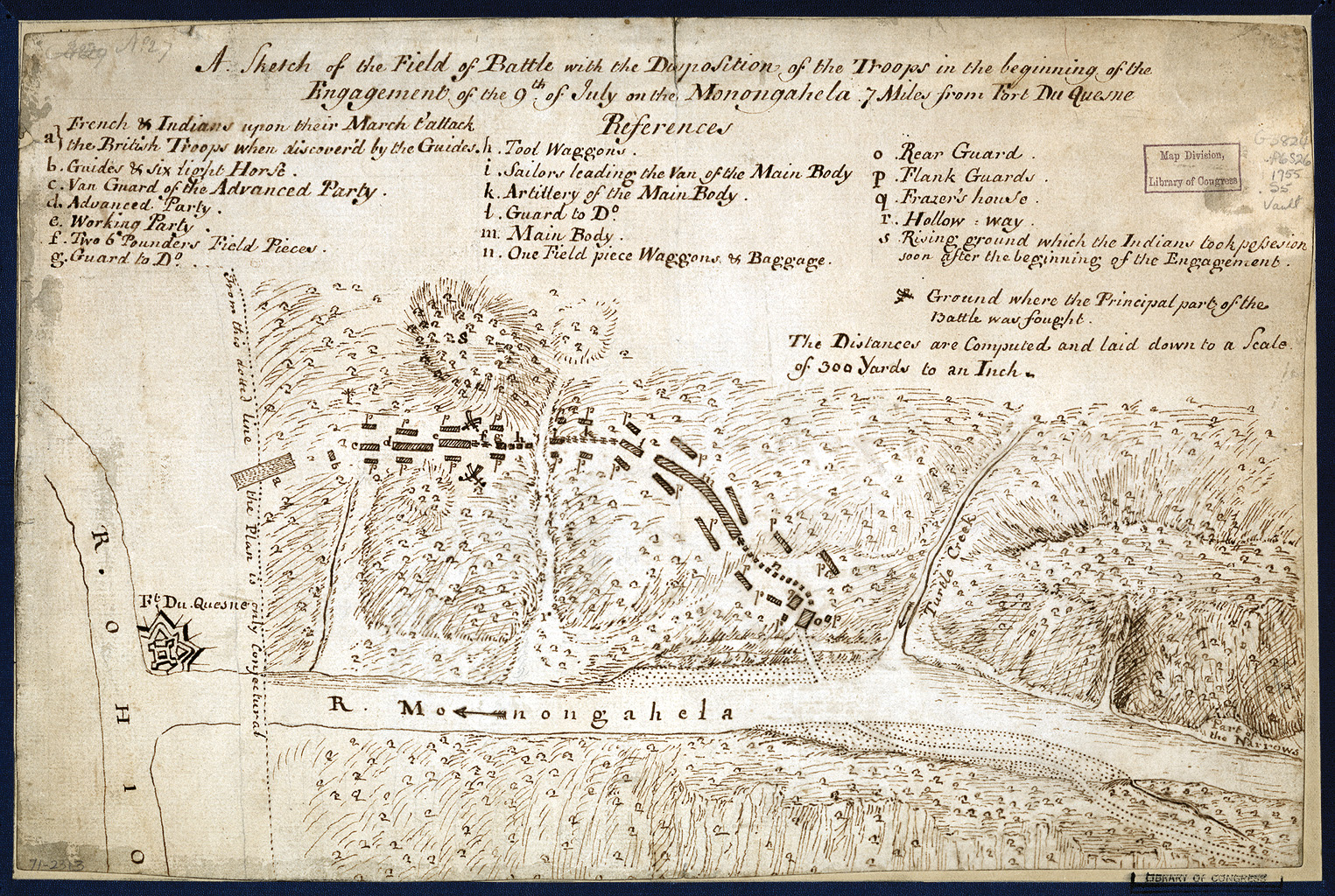

Nearing Fort Duquesne on July 7, Braddock’s force approached a sharp bend in the Monongahela River. Along this two-mile stretch, which became known as the Narrows, the road ran along a slender ledge of beach on the bank. The road needed considerable work to make it passable for the wheeled vehicles. To their left was the river, and to their right were steep cliffs that soared high above the river. It was the perfect location for an enemy ambush. By proceeding, the column risked being trapped and annihilated.

Rather than risk an ambush in the Narrows, Braddock opted to avoid that dangerous stretch by fording the Monongahela. Once on the southern bank, the column would march two miles past the Narrows to another ford and cross the river again. Both fords were shallow and offered easy passage; after the second crossing, thet would be just nine miles from their objective.

Indian scouts informed the French at Fort Duquesne of Braddock’s progress. The fort, which was made of logs and earth, was a small quadrilateral. Its rudimentary nature meant that it could withstand a siege. French deserters who provided the English with a plan of the fort stated there were only eight guns mounted, and half of them were inconsequential 3-pounders. The high ground on the opposite side of the Monongahela River offered a prime spot for Braddock’s siege guns to bombard the fort.

On paper, Contrecoeur commanded approximately 1,600 men, the majority of whom were Indians. The reality was that many of these troops were scattered across hundreds of miles of wilderness. Some of the troops were in the process of hauling supplies and ammunition to the fort.

Fort Duquesne’s regulars belonged to the Compagnies Franches de la Marine. Under the administration of the French Navy, the units were independent companies of infantry assigned to guard naval bases as well as the overseas colonies. Most of the enlisted men in the North American companies came from France, but many of their officers were Canadian-born soldiers well experienced in the combat tactics and conditions of the frontier. There was no regimental command, and the highest rank in the Compagnies Franches was captain. With the regulars assigned to the fort were militia recruited from inhabitants of the St. Lawrence Valley.

Unlike the British, the French had close relationships with many Indian peoples. Defending the isolated outpost was possible because upward of 700 Indian allies were encamped near the small fort. They belonged to approximately 20 Eastern Woodlands tribes, including the Ottawas, Hurons, Abenakis, Ojibas, and Delawares. Many of these, which were known as domiciled Indians, lived in villages in the shadow of French-Canadian missions or towns.

Duquesne had ordered Contrecouer to stay in command until the crisis was over. So the two senior officers present divided their responsibilities, with Contrecouer running the fort and Beaujeu taking charge of a preemptive strike force to ambush the British. It is possible that another officer, Ensign Charles-Michel de Langlade, the son of a French-Canadian fur trader and the sister of an Ottawa chief, devised the ambush. Yet another officer, Captain Jean-Daniel Dumas, would later claim that he crafted the ambush plan. Any of these French officers would have known that the terrain around the Narrows and Turtle Creek offered many choice spots for ambushes.

Beaujeu wanted to set out on July 8 and hit the enemy as far as possible from the gates of Fort Duquesne. But when he revealed his plans to the allied Indian chiefs, they were reluctant to join the attack. Some reports exaggerated Braddock’s strength as upward of 4,000 men. Despite Beaujeu’s pleas, the best he could get was a promise that the chiefs would consider his plans overnight.

Braddock’s men broke camp early on the morning of July 9. At 2 am Gage led the advance party and a pair of 6-pounders toward the first ford of the Monongahela. The work party followed at 4 am, and the rest of the army marched one hour later. Gage reached the second ford at 9:30 am followed by the rest of the army.

Forever etched in Washington’s mind was the majestic spectacle that the British troops created that morning as they marched in full uniform through the deep woods. The soldiers in the long columns marched with precision. Occasionally the sunlight penetrated the forest canopy to flash momentarily from their burnished arms. As they marched in step, the river flowed lazily on their right, and the emerald forest flanked them on their left. After a perfectly peaceful crossing, scouts and flankers moved out to cover the work party, which continued cutting the wilderness road that would bear the name of the commanding general. The rest of the army settled down to its midday meal.

Meanwhile, Beaujeu led most of the garrison troops through the gates of Fort Duquesne after a quick morning mass by Chaplain Father Denys Barron. With Beaujeu were 36 officers and cadets and 72 enlisted men of the Compagnies Franches de Marine, with 146 Canadian militia.

Beaujeu visited the assembled chiefs in a council house. “I am determined to meet the enemy,” he said. “Will you let your father go alone?” His persuasive speech inspired approximately 600 Indians to follow him, and the combined force left at approximately 9 am. Half of the Indians soon detached themselves to march by another route.

At the head of Braddock’s column were their guides and a half dozen Virginian light horsemen. Behind them was Gage with 300 troops including two grenadier companies and Captain Horatio Gates’s Independent Company of regulars from New York. Then came the work party, the two 6-pounders, and a rear guard. The rest of the column was close behind. Although no scouts were out very far ahead of the army, flanking parties paralleled it along both sides.

At about 1 pm the guides crossed a dry ravine and soon drew near a small creek. Henry Gordon, an engineer, walked ahead to mark the path of Braddock’s Road for the work detail. Gordon spotted a mysterious figure in the woods, dressed in Indian style, but wearing around his neck the shiny metal gorget of a French officer.

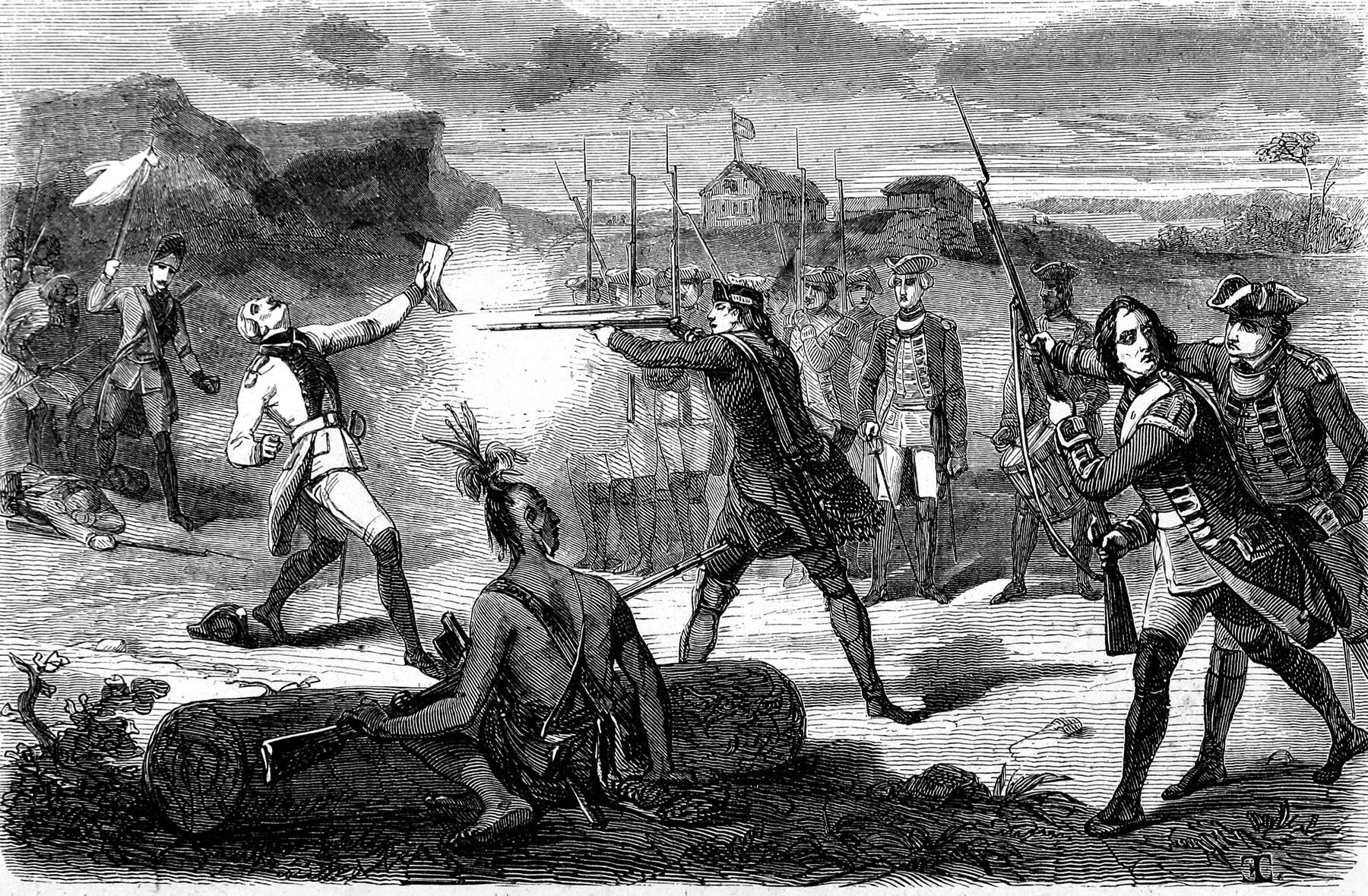

The Indian with the gorget was none other than Beaujeu himself, leading his men. Beaujeu was apparently as surprised to stumble upon the enemy troops as the redcoats were to see him. He was visible waving his hat and calling to his men, who rushed off the trail when they saw his signals and formed into a rough semicircle blocking the British column.

Far from unfolding as the stealthy ambush Beaujeu had planned, the Battle of the Monongahela opened badly for the French. Although surprised, the British held steady. Gage’s grenadiers pressed forward in good order and fired several volleys, and his 6-pounders soon went into action. Beaujeu was shot dead only moments into the battle.

Dumas took command of a perilous situation, which moment by moment grew worse for the French. One of Dumas’s lieutenants was killed and two other officers were wounded. Many of the French-Canadian militiamen fled after they learned their commander was killed. The battle began to look like a disaster in the making, and the Indian contingent began melting away. Despite the smoke and heavy undergrowth, the British saw their enemies were running and they raised a cheer.

It crossed Dumas’s mind, he later wrote, that death was preferable to watching his command fall apart. But the captain stayed where he was. Responding to his air of confidence, his remaining men settled down behind trees, stumps, and logs to return the grenadiers’ fire.

Around this time the Indians who had marched separately from the fort rejoined Dumas. Few of the Indians were accustomed to the firing of a cannon; however, it was quickly apparent that although the big guns made a fearsome display, they held little danger for widely scattered and well-hidden foe. Seeing that Dumas anchored an unyielding line of soldiers, the Indians slipped ahead and found firing positions along the enemy flanks.

Gage’s men stopped cheering as they realized the enemy was beside and behind them. One British soldier described the sound of the enemy fire as “poping (sic) shots, with little explosion, only a kind of Whiszing noise; (which is proof that the Enemys Arms were riffle Barrels).” A dozen grenadiers fell in only a few minutes. Around them the British saw a dark landscape thick with timber, fallen trees and logs and heavy brush. There was no open space other than the just-carved narrow road, which was now packed with British soldiers who were exposed to fire from all directions. Gage’s surviving men wavered and then fled back toward the main force.

Braddock responded to the emergency by leaving 400 troops with Colonel Peter Halket to guard the baggage and rushing forward with the rest of his men. Gage’s fleeing troops ran headlong into them, scrambling Braddock’s disciplined formations. All the while, Dumas and his men pushed closer, and the firing of the Indians intensified. The redcoats knew how to stay together in line and fire massed volleys at opposing formations in front of them. The grim smoke-shrouded woods offered no particular targets. Indeed, many survivors later claimed that they literally never saw any of their enemies during the battle. Unable to tell front from flank, the British troops bunched together into shapeless crowds a dozen or more men deep, unable to return fire with any effect.

Some of the provincials fought the enemy in their own style, scattering to find firing positions sheltered by trees or logs. Surrounded as they were, each of the colonials was protected only from some angles. Artillery was useless. Firing cannons at random into the labyrinth of dark trees was like shooting at needles in a haystack. Fearing the worst, the civilian drivers abandoned their wagons. Cutting the horses loose, the drivers mounted and galloped away toward Dunbar’s detachment.

Officers, in their distinctive uniforms, were easy targets. William Shirley, Braddock’s military secretary, died instantly from a bullet to his head. When Colonel Halket was shot dead his son, Lieutenant James Halket, ran to him. An instant later, the lieutenant’s lifeless body fell across that of his father.

Braddock’s horse was shot from under him. Mounting a fresh animal, that horse too fell within moments. Prominent Pennsylvanian James Burd conveyed to Pennsylvania Governor Robert Hunter Morris that Braddock’s soldiers pleaded with the general to allow them to take cover behind trees to return fire. Braddock denied permission and “stormed much, calling them Cowards and even went so far as to strike them with his own Sword for attempting the Trees,” wrote Burd.

The general’s attention focused on a hill to the right of the road, where persistent fire poured from the woods. Braddock ordered Lt. Col. Ralph Burton of the 48th Foot to charge the hill, but the officer could rouse no more than 100 men to follow him. When Burton was hit, the attack collapsed and his men surged back into the chaotic tangle of soldiers milling about in the road.

Braddock’s men expended their ammunition with little effect. Many men fired wildly into the air. Visitors to the site in 1776 reported that “the marks of cannon and musket balls are still to be seen on the trees, many of the impressions are twenty feet off the ground.”

“Wherever they saw a Smoak or Fire,” wrote Burd, the redcoats shot at it. Hardly any of their bullets struck an enemy, but the regulars’ uncontrolled firing decimated their own comrades in the flanking parties and the provincial soldiers fighting under cover. After the battle, Washington agreed with other survivors who estimated that “two-thirds [of the dead and wounded] received their shot from our own cowardly Regulars, who gathered themselves into a body, contrary to orders, ten or twelve deep, would then level, fire and shoot down the men before them.”

Many soldiers saw Washington, the last of the general’s aides who was not out of action, trying to steady and organize the men from horseback. Likewise, Braddock galloped through the battlefield, mounting fresh horses when his mounts were shot dead. He was on his fifth horse of the action when an enemy ball tore through his right arm and ripped into his lungs.

“This Confusion lasted about two hours and a half,” wrote Orme. “When their general fell, panic engulfed the British troops … the whole ran off crying the devil take the hindmost.”

Although the rank and file ran, many officers were conspicuous in trying to stem the rout. Three fourths of the British and American officers were killed or wounded. Washington “had two Horses shot under him and his Cloaths shot thro’ in several Places, behaving the Whole Time with the greatest Courage and Resolution,” wrote Orme.

In full panic, the survivors stampeded to the ford and waded into the river. Engineer Henry Gordon, his right forearm shattered by a bullet, rode to the crossing but found it was completely clogged with fleeing men. Looking for another crossing point, part of the sandy bank crumbled away under him, but his horse stayed upright and Gordon kept his seat. Forty yards into the river, Gordon glanced back and saw the enemy pressing closer. He observed some of the Indians scalping both the wounded and the female camp followers who fell into their hands. Others fired into the river at the retreating British. One Indian bullet pierced Gordon’s right shoulder, but he stayed on his horse and made it across.

Dumas watched the enemy rush across the Monongahela, but he was unable to press on and destroy the remnants of the Anglo-American army. The battle won, the Indians and militia would not heed orders to continue the pursuit, but fell to looting. There was plenty of plunder there for the taking. Eight guns and seven mortars were abandoned with their ammunition and equipment, not to mention hundreds of muskets left by the dead or dropped by soldiers in flight. A French account claimed the capture of more than 400 horses and 100 beef cattle. Also taken was the money tumbrel, which held about £2500 in coin, and Braddock’s confidential orders, papers, and maps.

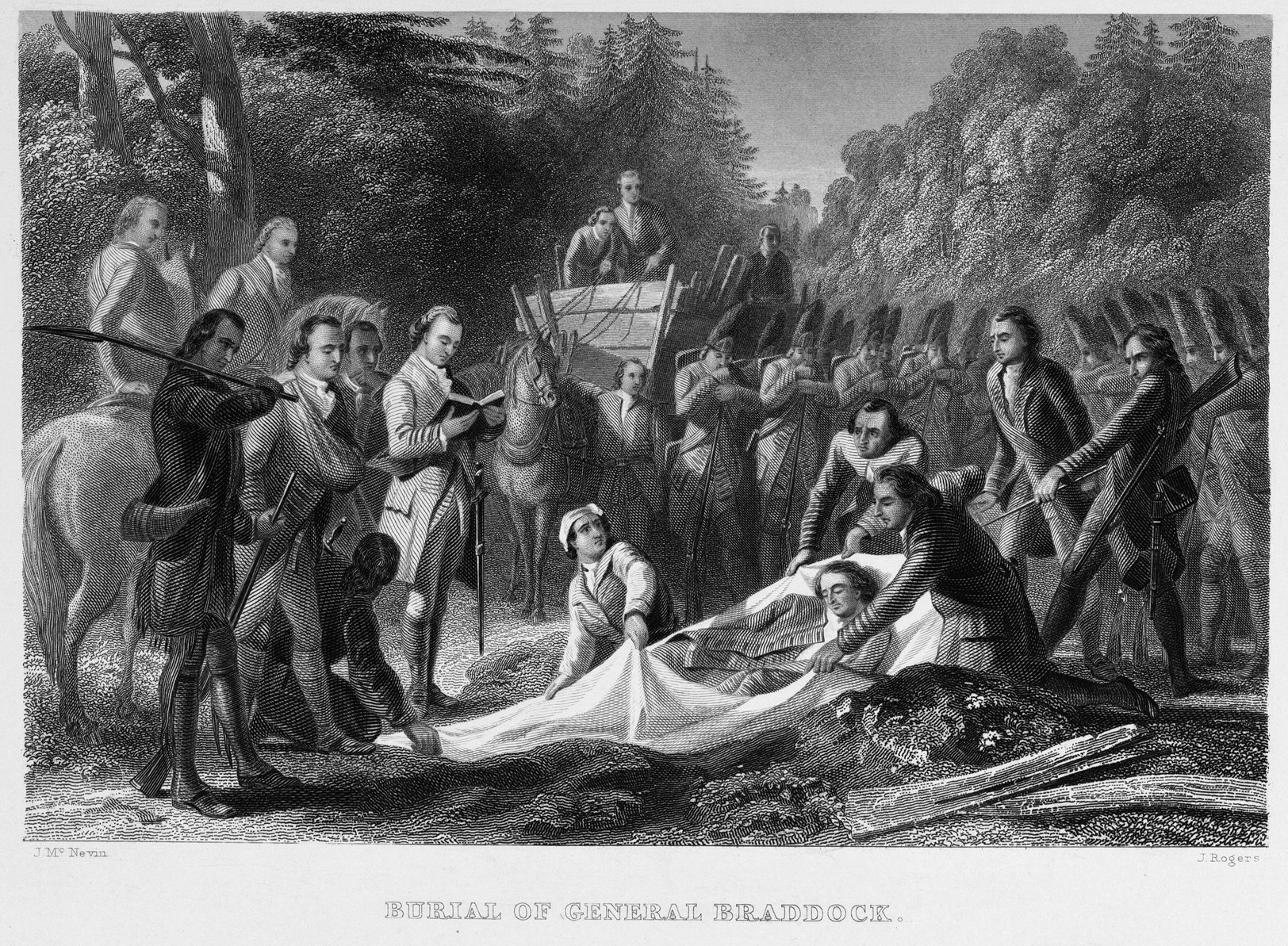

Braddock begged to be left to die on the battlefield, but several officers carried him away. Orme promised several soldiers a guinea and a bottle of rum apiece if they bore the general in a litter. They conveyed the wounded officer to Dunbar’s camp on July 11. Most of the survivors were already there. The Pennsylvania Gazette reported that at 5 am on the day after the battle, the first panic-stricken straggler made it to Dunbar’s camp.

The dying general saw no option but a fast retreat to the safety of Fort Cumberland. He ordered the destruction of most of the expedition’s supplies. Dunbar and the other British field officers carried out the orders. Most of the wagons were put to the torch. Soldiers broke open kegs and poured tons of gunpowder into a spring. They buried the Coehorn mortars saved from the battlefield and dumped or burned most of their remaining supplies.

“We shall know better how to deal with them another time,” Braddock said before succumbing to his wounds. Orme, who was seriously wounded and lying near the general, recorded the general’s last words for posterity. After the general’s death on July 14, he was buried in an unmarked grave in the road his troops cut through the wilderness about one mile from Fort Necessity. Marching away from the campsite, the survivors of the expedition marched over the gravesite, leaving no trace of its location.

Engineer Patrick Mackellar tallied a precise 457 killed and 519 wounded, out of a total of 1,459 men. A witness later claimed that a 1758 British expedition reached the site and buried 450 skulls. Other casualty totals vary, but all state that two thirds of Braddock’s advance force was killed or wounded. Surgeons found graphic evidence of the toll taken by friendly fire. Many bullets they extracted were of the large-size British military issue, rather than the smaller caliber balls common in French-Canadian and Indian frontier muskets.

Had Beaujeu lived he would have basked in the major accomplishments of routing Braddock’s larger army and saving Fort Duquesne. The cost to France of this strategic coup was the sort of losses one would expect in a skirmish. Including Beaujeu, only three officers were killed. Four officers, one of whom died on July 30, were wounded. Enlisted casualties ran to five men dead and four wounded, and only 27 Indians were reported killed or wounded. Nearly all of the casualties occurred during the confusion and surprise of the opening moments of the battle.

Washington came out of the disaster on Braddock’s Field with lasting respect for his courage under fire and his clear-headed leadership. In 1775 the fledgling Continental Army could look with confidence upon Washington as a military commander.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments