Dy Gerald Astor

In the late afternoon of April 6, 1945, five days after American GIs and leathernecks scrambled onto an Okinawa beach a scant 500 miles from Japan, two U.S. submarines, Hackleback and Threadin, lurking around the Bungo Suido exit from the Inland Sea, observed the passage of 10 Japanese warships, including a very large one.

Last Remaining Pride of the Imperial Navy

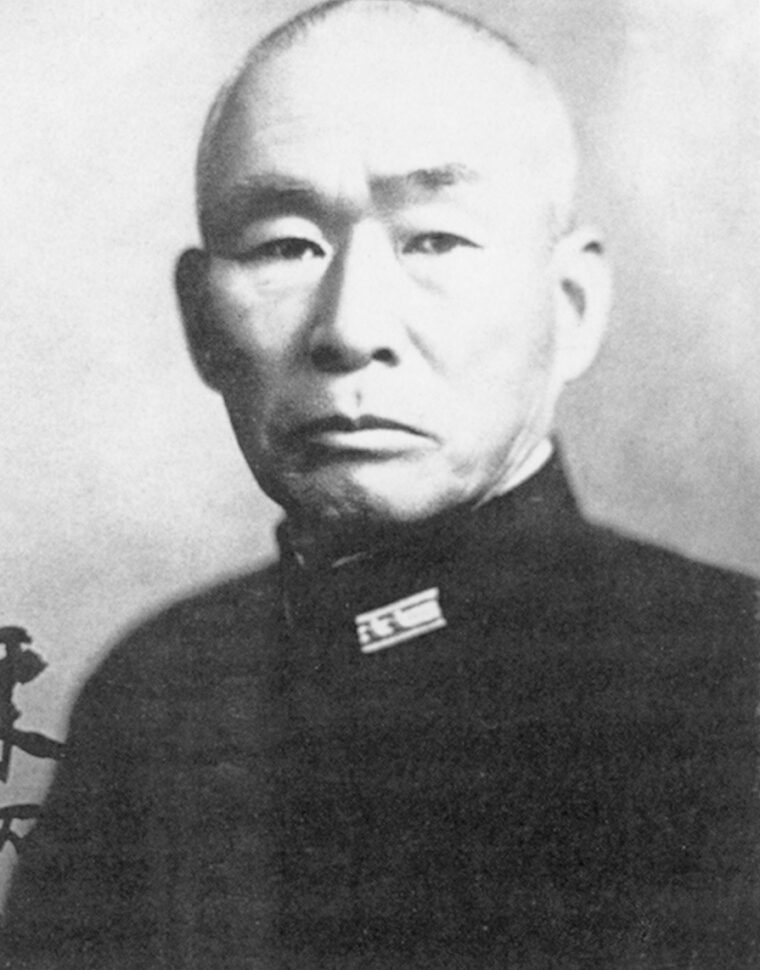

In the dim light through the periscope, a sub skipper guessed the biggest enemy vessel was an aircraft carrier. In fact, it was the last remaining pride of the Imperial Navy, the mighty battleship Yamato, under full steam. Escorted by a light cruiser and eight destroyers in the East China Sea, the Yamato could only be bound for the American anchorage off Okinawa. The Japanese task force was under Vice Adm. Seiichi Ito with Rear Adm. Kosaku Ariga in command of the Yamato.

Under orders to report but not attack, the submarines advised the Pacific Fifth Fleet headquarters of their sightings. Alerted by a radio message, Rear Adm. Morton Deyo, commander of the American gunfire and bombardment forces off Okinawa, prepared to execute a battle plan that would dispatch six battleships, seven cruisers, and 21 destroyers to intercept the Yamato and its cohorts. Deyo’s superior, Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, advised, “Hope you will bring back a nice fish for breakfast.” But even as Deyo scribbled his reply, “Many thanks, will try to,” the radio crackled news that Task Force 58, Vice Adm. Marc Mitscher’s fast carrier group, had picked up the scent and was already launching an airborne attack. Deyo then added the comment, “If the pelicans haven’t caught them all.”

A Formidable Vessel From an Earlier Era

Displacing 68,000 tons with nine huge 18.1-inch guns that measured 70 feet in length, the oversize Yamato dwarfed any vessel in the U.S. Navy. Built in secrecy to evade treaties restricting the size of the Japanese fleet, the Yamato, along with its sister heavyweight, the Musashi, boasted armor plate more than 25 inches thick. Launched before the raid on Pearl Harbor, the pair threatened American domination of the sea. But as World War II progressed, the aircraft carrier had swiftly eroded the traditional primacy of surface firepower.

The rather elderly battleships mustered by Admiral Deyo matched up poorly against the Yamato. While the Japanese behemoth could toss its ordnance 45,000 yards, the best efforts of the Americans would fall almost two miles shorter. But in theory, the half-dozen U.S. dreadnaughts, bolstered by a full complement of cruisers and destroyers, might outmaneuver the much smaller enemy fleet and overcome the advantages possessed by the Yamato.

During the first months of the war, Yamato and Musashi had followed the lead Japanese strike force that aimed at Midway Island in June 1942. But after the U.S. Navy destroyed four enemy aircraft carriers, the Imperial Fleet retreated, leaving the pair of monsters to vainly wander the Pacific for two years, searching for a chance to wield their enormous cannon while dodging American bombers and carrier planes.

Yamato Nicked Up During Largest Naval Battle In World History

Opportunity beckoned during the U.S. invasion of the Philippines in the fall of 1944. As General Douglas MacArthur sloshed onto a Leyte Island beach to pronounce, “I have returned,” armadas from the United States and Japan sailed toward a shoot-out in Leyte Gulf in what would be the largest naval battle in world history. One of several Japanese task forces, a flotilla that included Yamato, Musashi, and three other battleships plus a cohort of powerful escorts, but bereft of any real fighter screen, plunged into Philippine waters. American torpedo bombers, virtually unmolested, pummeled the intruders. In a day-long assault, nearly 40 torpedoes and bombs smashed into Musashi before the huge ship finally capsized and sank. The Yamato fared better, suffering minor damage. However, the remaining giant fled the scene with its companions.

Since then, the Yamato, as a floating bastion prepared to defend Japan itself against invasion, had stuck close to its home base at Tokuyama. But now, with the enemy ashore on Okinawa, on the doorstep of the Home Islands, the High Command ordered Yamato on what even the most optimistic considered a suicide mission. Strategists hoped the battleship’s vast firepower would distract the Americans enough to allow a massive kamikaze strike to penetrate U.S. defenses and destroy the fleet off Okinawa.

Naval Kamikaze Mission Proposed For Yamato

One preposterous scenario proposed that if the Yamato could stagger through the enemy gauntlet and the ship could first empty its arsenal of 3,200-pound shells at the American troops, it might then beach itself. The nearly 3,000 crewmen would surge ashore to act as ground soldiers. Some reports claim the Yamato had only enough fuel for a one-way voyage, but author George Feifer’s research indicates the vessel held enough for a return, unlikely as the possibility might have been.

With the discovery that it had left its sanctuary, the race to sink the Yamato was on. Seemingly, the contest pitted the seagoing U.S. warships against the dive-bombers and torpedo planes from its flattops. But the American men-of-war would never have a shot at the target. A prowler from the carrier Essex caught sight of the Japanese warships. Then, early on April 7, a pair of Marine twin-engine flying boats, hovering just out of range of the enemy antiaircraft guns, tracked the prey for five hours.

When the distance from Task Force 58 narrowed to 250 miles, Vice Adm. Mitscher launched his planes; some 280 dive and torpedo bombers comprised the initial waves. Ensign Harry Jones, a native of Pittsburgh in an Avenger from Torpedo Squadron 17 aboard the carrier Hornet, recalled, “Scuttlebutt on the ship had it that the battleship admirals who outranked the air admirals wanted to shoot it out with the Japanese. But the Yamato’s guns were bigger than anything we had and the air admirals won out. We would intercept them.

In Hot Pursuit Of a Big Fish

“We took off from the Hornet, seven torpedo bombers plus fighters and dive bombers. The torpedo planes, which had search radar, did the navigation and it was a poor day for flying, rainy, misty, a lot of scud, not much ceiling. The flight leader from another carrier developed engine trouble and turned the lead over to our air group, bossed by Comdr. E.G. Konrad, a Naval Academy graduate.

“The lead pilot said they ought to be in range, but we couldn’t see anything on radar. Konrad said stay on course. One plane radioed he saw a blip off to starboard about 50 miles out and we turned right. Then we saw them. Holy Mackerel! The Yamato looked like the Empire State Building plowing through the water. It was really big. We orbited around out of their gun range. They opened up with main batteries, 18-inch guns. What was surprising to us was that there were no Japanese aircraft around even though we were very near their home islands.”

Unprotected Yamato Relies On Its Big Guns

In a fatal decision for the Yamato and its companions, the Imperial Navy had decided to reserve almost all available aircraft for kamikaze missions. Less than a half-dozen Japanese fighters appeared on the scene, and they were quickly overwhelmed. In its own defense, the Yamato possessed awesome weapons. Extra guns had been added to an already prodigious array of antiaircraft firepower, six 6-inch secondary batteries, 24 5-inch antiaircraft guns, and 150 machine guns, along with all that the escorts could throw up. A special new shell equipped with a time fuse exploded into 6,000 deadly pieces. To ward off low-flying torpedo planes, the battleship’s big guns blasted giant waterspouts. But none of these defenses could deal with strikes by so many aircraft manned by skilled airmen.

At 12:32, the Yamato had opened up on the approaching aircraft. According to Avenger pilot Harry Jones, “The air boss gave us the order of attack. He said, ‘Shasta,’ meaning those from the Hornet go in first. Then he read off the order in which the planes from other carriers would attack. We didn’t have too much ceiling. I was at 12,000 feet at most and usually liked to start at 18,000 feet for a torpedo run, a steep approach and then right over the water, drop the torpedo and then get the hell out of there. Meanwhile, the bombers are supposed to be going down, so we all hit the ship simultaneously.”

American Planes Draw Blood

Confusion continues about who actually scored the initial hits. Some accounts report that bomb-laden Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters from the Hornet actually struck first, targeting the destroyers and the light cruiser Yahagi that formed a diamond shape surrounding the battleship. The fighter-bombers claimed two hits, and Lt. Cmdr. M.U. Beebe, the squadron honcho whose plane bore no bomb, zoomed in for a strafing run at the Yahagi. Hellcats from other ships also blasted the escorts. Their mission was to suppress and draw off fire, enabling the other attackers to zero in on the main target, Yamato.

In the assault on the cruiser Yahagi and the destroyers, a swarm of Grumman Avengers, armed with torpedoes set to only a 12-foot depth, zeroed in on the smaller ships. Within a few minutes, the Yahagi lay dead in the water. Seven torpedoes and 12 bombs eventually devastated the cruiser. It foundered with only a handful of survivors left to tread water.

Avenger pilot Lieutenant Robert L. Mini, separated from the others in his flight because of cloud cover, glimpsed a destroyer. He dropped his tin fish while dodging flak bursts. “Bingo!” an exultant gunner shouted over the intercom. Aviation Machinist’s Mate Third Class William A. Baker saw the Mark 13 torpedo slam into the tin can with a fiery explosion.

Mini is credited with having blasted the destroyer Hamikaze. It sagged amidships, broke in two, and finally flashed its crimson underbody as it disappeared beneath the water. Three more of Yamato’s accompanying warships, battered beyond repair, were abandoned and scuttled. The surviving quartet of destroyers, all nursing serious wounds, would hang about long enough to pluck up some of those in the sea and flee to safety.

Stunned But Not Out, Yamato Punches Back

It was not, however, a day at the seaside for the American Navy. Lieutenant Norman A. Weise, concentrating on his destroyer quarry, accidentally passed within range of the Yamato’s antiaircraft batteries. Shrapnel from 25mm shells burst in the vicinity of Weise’s Avenger just as he released his torpedo. Jagged shards of metal ripped through his windscreen and into the cockpit. One splinter dug into his scalp while gasoline from a ruptured fuel gauge sprayed his face, temporarily blinding him. Fragments from another shell wrecked the radio compartment, wounding his gunner. His rudder and vertical stabilizer absorbed two more hits. Weise managed to guide his crippled plane back to a safe landing on a carrier.

Nine minutes after the opening salvo from the Yamato’s defenses, dive-bombers plunged down on the battleship at 400 knots per hour. A pair of thousand-pound bombs exploded near the mainmast, obliterating a radar room and a fire-control station. Avenger pilot Harry Jones recalled, “We spread out and I kept diving toward different puffs of smoke, where shells had already exploded. There shouldn’t be any damage there. There were two fighter planes in front of each of the torpedo planes. They were supposed to strafe the destroyers and probably draw some of the fire. I saw one of our replacement pilots in a plane take a direct hit and explode in the air. Down he went. I went down, dropped my torpedo and went right across the bow of Yamato. The ship was turning, but in our attack we always dropped in a fan shape so no matter which way a ship is turning, it is going to get hit. Our group was credited with two torpedo hits out of the seven planes, but the gun camera that showed my angle on the bow didn’t credit me with a hit.” From Jones’s VT-17, Lieutenant Thomas C. Durkin, the executive officer, actually registered the initial torpedo hit on the target.

Torpedo Depth Recalibrated To Strike Yamato’s Weaker Underbelly

When the first tin fish exploded against the battleship’s hull, however, it did little damage. The squadron’s Mark 13 missiles had been set for 12 feet below the surface, striking the Yamato where the armor was thickest. One of the reasons Mini and those in his squadron settled on the more lightly shielded cruiser and the destroyers had been the knowledge of their vulnerability to even shallow-depth torpedoes. Aware of the problem, VT-84 from the carrier Bunker Hill reset its weapons to dive deeper into the water, bringing them home below the Yamato’s protective iron plates.

Lieutenant Commander Chandler W. Swanson led VT-84 and instructed his people at the pre-takeoff briefing, “This squadron will attack the battleship and only in case of necessity will any pilot drop on any other target.” When they came within range of the Yamato, Swanson broke his 14 Avengers into two flights for an anvil-like approach. As they closed to drop their torpedoes, the Americans separated into groups of two and three, making a five-pronged assault.

“Our Planes Were Crisscrossing Over the Target From All Directions.”

Swanson reported, “As soon as we started diving from the overcast, they threw everything at us, including a barrage from the Yamato’s 16 [sic] inch guns. Puffs of purple, red, yellow and green flak blanketed the sky. It would have been beautiful if you didn’t know it was so deadly. Our planes were crisscrossing over the target from all directions. That was the most dangerous part of it. We had to keep from running into our own planes. There were so many of them and so little room to maneuver. It was surprising we had no collisions.”

One plane, hit by fire from the battleship, suddenly nosed down and then blew up when it smashed into the ocean. Undaunted, the others, jinking now and then to throw off enemy gunners, a mere 500 feet above the water, homed in. From a distance of less than a mile, torpedoes flopped smoothly into the sea and then swiftly darted toward Yamato. The vessel swerved in a vain effort to avoid the onrushing Mark 13s. But at 1:37, an hour or so after the action began, three torpedoes blasted the port side, doing significant harm. Moments later, another pair hammered the stricken battlewagon on the same side. Lieutenant W.P. Popp said, “It looked like Old Faithful geyser erupting when the torpedoes hit the Yamato.”

Death Blow Delivered

Seawater rushed into the gaping holes, and the ship began to list badly. Rear Admiral Ariga was forced to order flooding of the starboard-side engine and boiler rooms. A warning to sailors in these areas arrived too late, and several hundred men drowned at their posts. While the maneuver temporarily prevented the ship from capsizing, it slowed drastically with only a single screw still churning.

For Lieutenant j.g. Jack Speidel from VT-29, assigned to the light carrier Cabot, this was his second crack at the Yamato, since he had been among the aviators whose swipes at the ship during the battle of Leyte Gulf failed to inflict serious damage. Now, in the East China Sea, he arrived on the scene after the first blows at the Japanese giant and her escorts. “When we took off for the Yamato on April 7, we had one drop tank that gave us an extra hour of flying time. There was an overcast and one group never did find the Yamato. Everybody had to go through a single hole in that overcast, and there was so many planes it was incredible.

“I remember colored bursts in front of us and splashes in the water from enemy ships. We came in on the port side, not real low. Others had probably already hit the ship. After we dropped the torpedo and turned away, my radioman was watching and he screamed, ‘We hit it! We hit it!’” The history of the Cabot claims Speidel’s tin fish struck “directly under the bridge, causing a terrific explosion.”

Hiding From Japanese Ships In Freezing Waters

A pilot from the light carrier Belleau Wood, Lieutenant j.g. W.E. Delaney, made his attack at 1,400 feet, dropping four 500-pounders. As his plane passed over the battleship, he said, “There was a loud explosion under the fuselage. The cockpit filled with smoke and fumes. One wing was on fire. I was afraid the plane would explode and ordered my crew [a gunner and radioman] to jump. They bailed out five miles southwest of the Jap task force. I watched their parachutes open, then I jumped.” Unfortunately, although Delaney saw their chutes deploy, both men apparently drowned.

Delaney, after hitting the sea in the midst of the enemy vessels, managed to inflate his rubber raft. He stayed in the water, though, hanging onto the raft and hiding from the Japanese. A destroyer came within a hundred yards but veered off, apparently thinking there was no American survivor. “At first I was so cold,” said Delaney, “when the Jap can approached, I thought of giving up. But I decided they might shoot me. So I stayed behind the raft.”

Patrol Planes Aided Rescue Mission

The pilots from the two Marine flying boats, Lieutenant James R. Young and Lieutenant j.g. Richard L. Simms, still on station, saw Delaney floating amid Japanese sailors who had abandoned their sinking ships and clung to bits of wreckage. While Simms acted as a decoy to draw off any fire from the remaining enemy vessels, Young set down his patrol plane, took Delaney aboard, and flew him to safety on Okinawa.

According to Harry Jones, observation or scouting planes that ordinarily launched by catapult from the decks of battleships or cruisers had been ordered to tag along to perform rescues like the one that saved Delaney. “I remember a pilot from one of these came on the radio and said he was getting low on gas and was going to turn around. I heard what must have been a fighter pilot say, ‘If you turn around, you son of a bitch, I’m going to shoot you down.’”

On board the Yamato, Sakae Katano, a 26-year-old sub-lieutenant with a duty to organize repairs from air raids, made a futile attempt to restore operations. “Telephones were not working any longer and the ship started to heel. I left one of my men behind and took the rest to do the repairs. But while we were running there, a torpedo hit the right side of the ship. I closed the hatch and came up again. Our personal belongings were floating in the water, which came up to our knees.

Yamato’s Final Hours

“The flag could no longer be seen and I thought nothing more could be done. I tried to go back to my men but found it impossible because of the water. I called my men; there were 18 of them and they came by. I ordered them to leave the ship, jump into the sea. They did not have enough courage to follow the order, so I jumped first. I say ‘jump’ but it was really a matter of sliding down the side of the ship. My men followed.”

Ensign Mitsuru Yoshida reported, “The desolate decks were reduced to shambles. Big guns were inoperable because of the increasing list, and only a few machine guns were intact. One devastating blast in the emergency dispensary had killed all its occupants, including the medical officers and corpsmen.”

The Yamato, considered a luxury ship by Japanese sailors ordinarily confined to fetid, spartan quarters, could only be described now as hell on water. Amid the continuing explosions of torpedoes and bombs, American planes methodically hosed the stricken ship with machine-gun fire. Steam from ruptured pipes scalded sailors; fire incinerated others; corpses and body parts littered the blood-soaked decks.

The Skipper Bound In The Bridge

It was apparent to those in command that the Yamato was doomed. Amid the wreckage and bodies strewn about the bridge, Seiichi Ito, as task force commander, signaled the other ships to abort the mission. Those still afloat would try to pick up some of the men floundering in the water and then head for port. Ito saluted, shook hands with some other officers, then locked himself in his cabin. He would go down with the battleship.

The Yamato’s skipper, Ariga, rather than permit hallowed portraits of the Emperor and Empress to suffer the indignities of capture, arranged for an officer to secure himself in a room with the artwork. Ariga then ordered a seaman to bind him to a binnacle on the bridge. There he chewed biscuits, awaiting his inevitable fate.

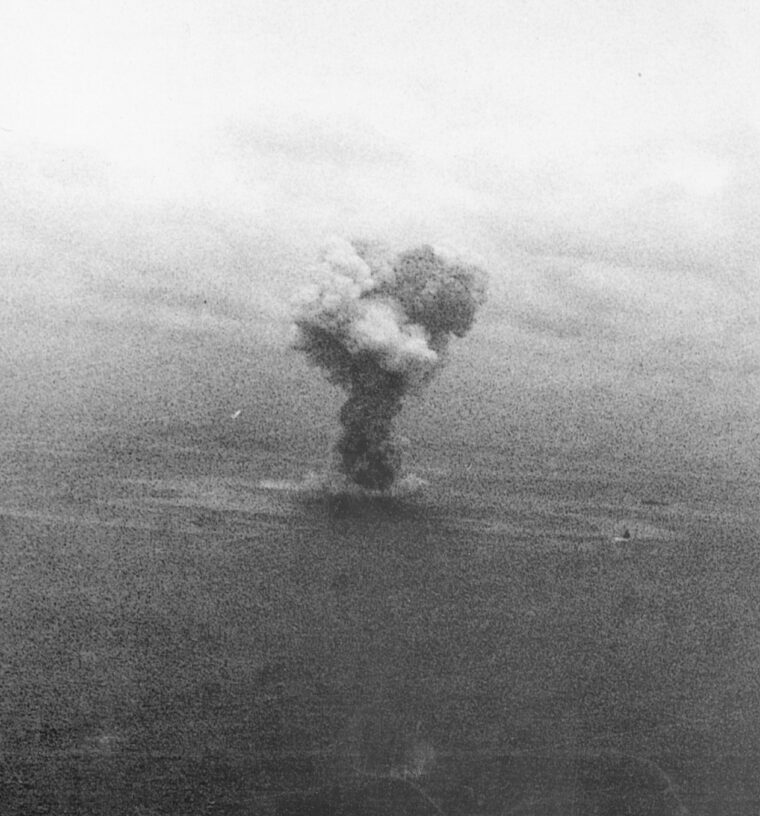

In the bowels of the battleship, fire cooked off ammunition magazines, inducing shattering convulsions of the infrastructure. The subterranean blasts erupted through the steel decks into a 6,000-foot tongue of fire stretching into the sky. A four-mile pillar of smoke trailed the Yamato. At 2:23 in the afternoon, the great ship rolled over and sank, dragging down with it some 2,500 sailors. Only 269 survived.

Role Of the Battleship In Naval Warfare Comes To a Close

Sakae Katano recalled, “We kept swimming as a group for a while and saw the Yamato slide towards the ocean bottom. We gathered some lumber and made a raft, putting the injured men on it. By now there were only five or six of my men with me. I had a bad feeling for I knew there were sharks in the sea.

“American planes came strafing but after a while they were gone. Japanese destroyers began to appear, so we tried to swim to get near them. Because of the tidal current we couldn’t. Finally, we gave up and fell asleep on the raft. Then I heard voices and, when I opened my eyes, I found the destroyer Ukikaze nearby. I swam near it and was expected to climb a rope ladder to the ship. I ordered a crewman on the destroyer to throw a rope down to me. I looped the rope around my waist and put one end in my mouth so my teeth could hold it while they pulled me up. My hands were too slippery to hold the rope and besides I was too exhausted.

“After I was rescued, I went to see one of my men. I offered him a cigarette but he could not take it. He was completely armless and legless. He died while on the destroyer.”

The hopeless excursion by the Japanese task force ended with as many as 3,750 of its crews dead. Mitscher counted 10 aircraft and 12 airmen lost. The last remnants of the once-powerful Imperial Japanese Navy had been vanquished, and the role of the battleship permanently eliminated.

My Uncle Don was shot down attempting to drop a bomb on the Yamato. The rear gunner in his SBD2C dive bomber was killed. Uncle Don was captured and imprisoned in Japan until wars end. He was on an American freighter in Tokyo Bay nearby the Battleship Missouri when the surrender documents were signed.

Joseph Donald Brown was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for previous action over Kure. He survived to have 6 children and a long happy marriage.

R.I.P Uncle Don