By John Walker

As the year 1520 drew to a close, the half-starved inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, the magnificent capital city of the most powerful city-state in the Aztec Empire, found that they were threatened by a massive host of enemies, both foreign and indigenous, which was led by Spanish Captain-General Hernán Cortés and his small band of conquistadors.

Moctezuma II, the ninth emperor of the Aztec Empire, rose to the throne of the empire in 1502. He ruled over an empire whose heartland was the central valley of Mexico. The Aztecs, though, never subjugated the Tlaxcalans or Tarascans. The empire was a Triple Alliance of the three tribes with a combined population of roughly six million. Tenochtitlan was home to upwards of 200,000 Aztecs.

Cortes had landed on the coast of Mexico in early 1519 with 550 men. As he marched inland in the late summer, he initially encountered the Tlaxcalans. The Tlaxcalans surrendered to the Spanish in September after losing a string of battles. Moctezuma planned an ambush of the Spanish, but the Tlaxcalans warned Cortes in time to save his troops. When Moctezuma learned that Cortes had been able to avoid the ambush, he believed that only a god could have known of it in advance. Suspecting that he might be the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, Moctezuma welcomed Cortes into Tenochtitlan on November 8. The Spaniards not only took Moctezuma prisoner, but also attacked and killed some Aztec nobles.

In the second half of 1520, the Aztecs had suffered through the deaths of two of their emperors, Moctezuma II, who was followed by his brother Cuitláhuac, as well as a devastating 70-day epidemic of smallpox that ravaged every part of the city and claimed the lives of 100,000 people. “When the Christians were exhausted from war, God saw fit to send the Indians smallpox,” wrote Alfonso Aguilar, a conquistador who participated in the expedition. “In Tenochtitlan, the streets were so filled with the dead and sick people that our men walked over nothing but bodies.”

Worse still, the huge death toll had quickly resulted in a dearth of able-bodied workers available to grow and harvest crops, leading to massive food shortages, starvation, and eventually famine. After Cuitláhuac perished from the pox on December 4, 1520, having ruled for just 80 days, Moctezuma II’s 18-year-old nephew, Cuauhtémoc, was chosen the new emperor. Cuauhtémoc had argued strenuously, but unsuccessfully, against allowing the conquistadors into the city.

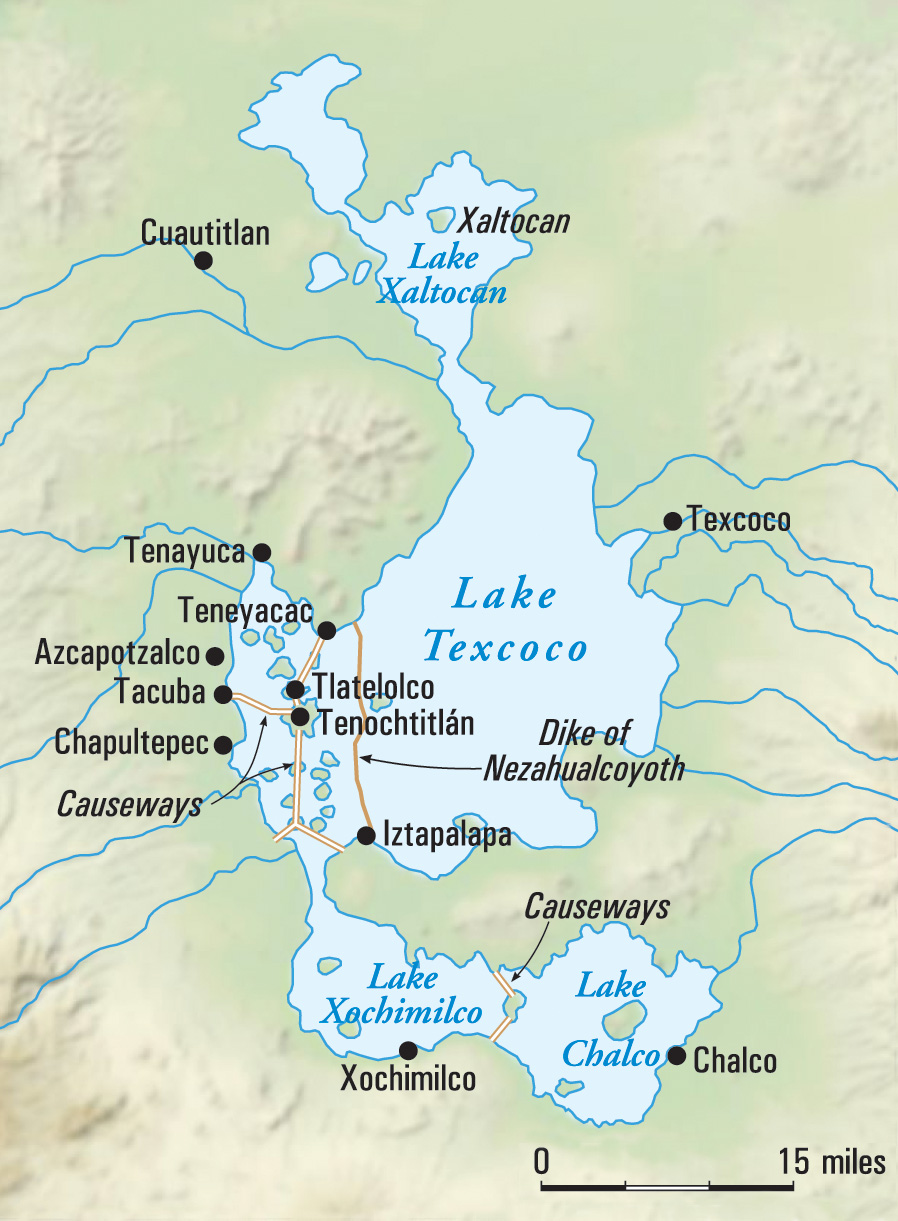

The Aztec Empire had become far and away the most dominant city-state in the Valley of Mexico well before Moctezuma II was chosen to be the emperor in 1502. In 1427 Aztec warrior-lord Itzcoatl, after forging a coalition between the cities of Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tacuba, defeated and subjugated Azcapotzalco, the region’s dominant power during the 14th and early 15th centuries. The three victors formed the powerful Triple Alliance in 1428, which soon came to be dominated by Tenochtitlan, and began aggressively expanding the alliance’s borders in all directions.

At its peak, Tenochtitlán’s splendor, architecture, and sheer size rivaled anything found in Europe and the world. Nearly a quarter million people lived in the two island cities of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, which lay atop the waters of Lake Texcoco, and one million more Nahuatl-speaking natives lived in the cities and villages surrounding the lake and beyond.

Tenochtitlan was connected to the mainland by a number of elevated stone roadways known as causeways, each with several drawbridges, and was surrounded by thousands of floating gardens known as chinampas. These were vast fields that encompassed millions of acres of fertile soil, staked and constructed within the actual waters of Lake Texcoco itself, a brilliant innovation that enabled Tenochtitlan to supply most of its own food. The city was home to a huge stone aqueduct, a vast central marketplace that hosted crowds of 60,000 people daily, and flotillas of thousands of war canoes that seemingly made the city impregnable.

During his reign, Moctezuma II showed little mercy when enforcing his laws within the Triple Alliance and even less toward his enemies outside it, exterminating entire adult populations in communities that defied him and distributing tens of thousands of their children throughout the empire as slaves.

Although their massive army was rightly feared all through central Mexico, the Aztecs for generations had been unable to subdue the people of Tlaxcala. To keep them subordinate, Moctezuma II ordered numerous so-called flower wars, which were highly ritualized, staged battles between the best warriors from each city during which the participants attempt to only wound and subdue their foes, to be captured for human sacrifice later, rather than leave them dead on the battlefield.

Their overwhelming advantage in numbers almost always assured the Aztecs’ victory, and thereby the continuation of Tlaxcalan tribute in the way of goods and young men and women to be ritually sacrificed and eaten, which had gone on for decades. The emperor also imposed an economic blockade that cut Tlaxcala off from trade in cotton and salt. The compliance of its subject peoples depended entirely upon their constantly being reminded of the Aztecs’ prowess in battle.

Cortés and his men had been resting and recuperating in Tlaxcala after their harrowing escape from Tenochtitlán on July 1, 1520. By that point in time, the Aztecs had turned on the Spanish and besieged them in their compound. When Cortés sought to lead his army out of the city at night, it was attacked by the Aztecs. Cortés said he lost 154 Spaniards and 2,000 indigenous allies. The bloody event became known thereafter as La Noche Triste, or the Night of Sorrows.

While his troops were recovering from La Noche Triste, Cortés devised a new offensive plan of an unprecedented scope and magnitude in comparison to his earlier battles. If he could not capture Tenochtitlán by land, he reasoned, he would do so by water.

With this in mind, Cortés tasked Martin Lopez, his carpenter and master shipbuilder, with building a fleet of shallow-hulled brigantines. To carry out the assignment, Cortés furnished Lopez with the best craftsmen in the army and a host of Tlaxcalan laborers and wood-gatherers. In their quest to build the brigantines, they salvaged wood and other hardware from the ships that Cortés had ordered destroyed when he landed at Vera Cruz in April 1519. Once the construction work was completed, the ships would be dismantled so that they might be transported over the mountains by thousands of porters. When the dismantled ships reached the shores of Lake Texcoco, they would be reassembled and launched.

Backed by 10,000 Tlaxcalan warriors supplied by his new ally Xicotencatl the Elder, Cortés departed Tlaxcala on December 26, 1520, and marched west into the Valley of Mexico. When he reached the outskirts of Texcoco, Cortés was approached by the rebel Texcocan warlord Ixtilxochitl, who offered his assistance, and that of his followers, in the offensive against Tenochtitlán.

The Spaniards and their Indian allies arrived at Texcoco the following day and found the city almost deserted. Many of the inhabitants had fled into the mountains, while many others, including the city’s ruler, Coanacochtzin, fled in canoes across the lake to Tenochtitlán.

Cortés angrily ordered what was now his usual punishment for cities that defied him. His troops sacked the city, slaughtered the adult males, and sold the women and children into slavery. He then named Ixtilxochitl the new ruler of Texcoco.

With little effort, Cortés had gained effective control over the second city of the Triple Alliance, whose strategic location on Lake Texcoco’s eastern shore and its rich agricultural surpluses would serve Cortés and his troops well in the months ahead. The conquistadors, who did not have to answer for their actions to the crown of Spain, acted as a law unto themselves for almost four decades. They destroyed and founded cities at will and enslaved conquered people as part of the plunder of war.

When news of Texcoco’s fate became known, ambassadors from cities around the region began arriving at Cortés’ court to offer their submission. Cortés knew by then that the Chalca city-states south of the lake, which had been conquered in 1464, were reluctant tributaries of the Aztecs and eager to defect.

With possession of the strategic city of Iztlapalapa a key to his success, Cortés led 200 Spanish infantry, 18 horsemen, and 8,000 Allied warriors against the city and captured it with surprising ease. The Spanish conqueror and his allies realized too late, though, that they had walked into a trap. Having abandoned the city, the Aztecs breached the Dike of Netzahuacoyotl, which separated the salt water in the eastern section of the lake from the smaller body of fresh water in the western portion. This drowned dozens of Spaniards and hundreds of Tlaxcalans. At dawn the Spaniards and their allies conducted a fighting retreat in the face of overwhelming numbers and began their return to Texcoco.

Despite the embarrassing setback, envoys continued to arrive at Cortés’ camp ready to pledge their allegiance to the captain-general. Lopez arrived with the fleet of 13 brigantines in late January 1521. The craftsmen and laborers immediately undertook the time-consuming process of reassembling the vessels. From his base in Texcoco, Cortés launched a series of spoiling attacks the following month to keep the Aztecs off balance. In the first foray around the lake’s northern shore, Cortés took Xaltocan on February 3 with the assistance of 10,000 Tlaxcalans. The conquistadors found the cities of Cuauhtitlán, Tenayucan, and Azcapotzalco had been abandoned, and they quickly occupied them.

When he arrived at Tacuba on the landward side of Tenochtitlán’s western-facing causeway, the route the Spaniards and their allies had taken on La Noche Triste, Cortés found the Aztecs had constructed formidable defenses in that sector. The Aztecs had rallied in massive numbers to support the only remaining city-state of the Triple Alliance other than Tenochtitlán. The Spanish and their allies launched repeated charges, through which they eventually succeeded in dislodging the Aztec defenders.

When Cortés tried to exploit this success by seizing the Tacuba causeway, the Aztec drew him in until he was exposed, deployed their war canoes on both Allied flanks, and opened fire with a withering barrage of arrows, spears, stones, and darts. After losing a number of men killed, wounded, and captured, Cortés and the survivors withdrew after a day of fighting and headed back to Texcoco. When Cortés and his men arrived there on February 18, Cortés knew his decision to order the construction of a fleet of brigantines had been a good one. Without naval power to wrest Aztec control of the lake, he could not secure the causeways, and without the causeways he could not invest Tenochtitlán.

Yet there was good news from the coast. Supply ships from Hispaniola and Cuba continued to arrive at Vera Cruz unmolested. They brought fresh troops and horses, as well as badly needed gunpowder and weapons. The Spanish crown had finally given its long-awaited approval to Cortés’ expedition.

Rather than returning to Cuba, as ordered by Cuban governor Diego Velásquez, after he led a brief exploratory mission of the coast of the Aztec Empire, Cortés led his small band of 600 conquistadors into the Valley of Mexico, fully intent upon advancing the interests of the Spanish Crown and Roman Catholic Church while acquiring fame, status, and vast riches for themselves in the process. The Chalca city-states to the south, though, were being raided by the Aztecs and pleading for help. In response to their pleas, Cortés dispatched a force to assist them, and it succeeded in thwarting the Aztec attempt to retake Chalco on March 25.

Cortés then decided to pacify the entire southern region, leaving Texcoco on April 5 and leading 300 infantry, 30 horsemen, 20 crossbowmen, 15 arquebusiers, and more than 20,000 Texcoca-Tlaxcala allies against the city of Cuernavaca in Xochimilca territory. He made a rare mistake on April 11 when he encountered an Aztec force occupying the rocky heights of Tacuba city. Cortés split his forces and sent the various columns in a series of direct assaults up the steep slopes. The Aztecs hurled back each assault. The battle was a costly failure. Cortés admitted his mistake. Since the Aztec garrison had no access to water, it surrendered the following day.

Afterwards, Cortés marched on to Oaxtepec, which submitted without a fight. Although steep ravines offered formidable natural protection to Cuernavaca, Cortés launched a massive frontal assault that pinned the garrison down, allowing other units to roll up the enemy’s flanks and overwhelm the city. The victories won during the campaign secured the area south of the Valley of Mexico for the Spaniards, further isolating Tenochtitlán from sources of supply and reinforcement.

Cortés army countermarched northward, arriving at Xochimilco on April 16. His troops easily overwhelmed the Aztec defenses, but in the evening a large number of Aztec reinforcements arrived from Tenochtitlán. The Aztec commanders hoped to trap the Spaniards and their allies in the city by securing the causeway.

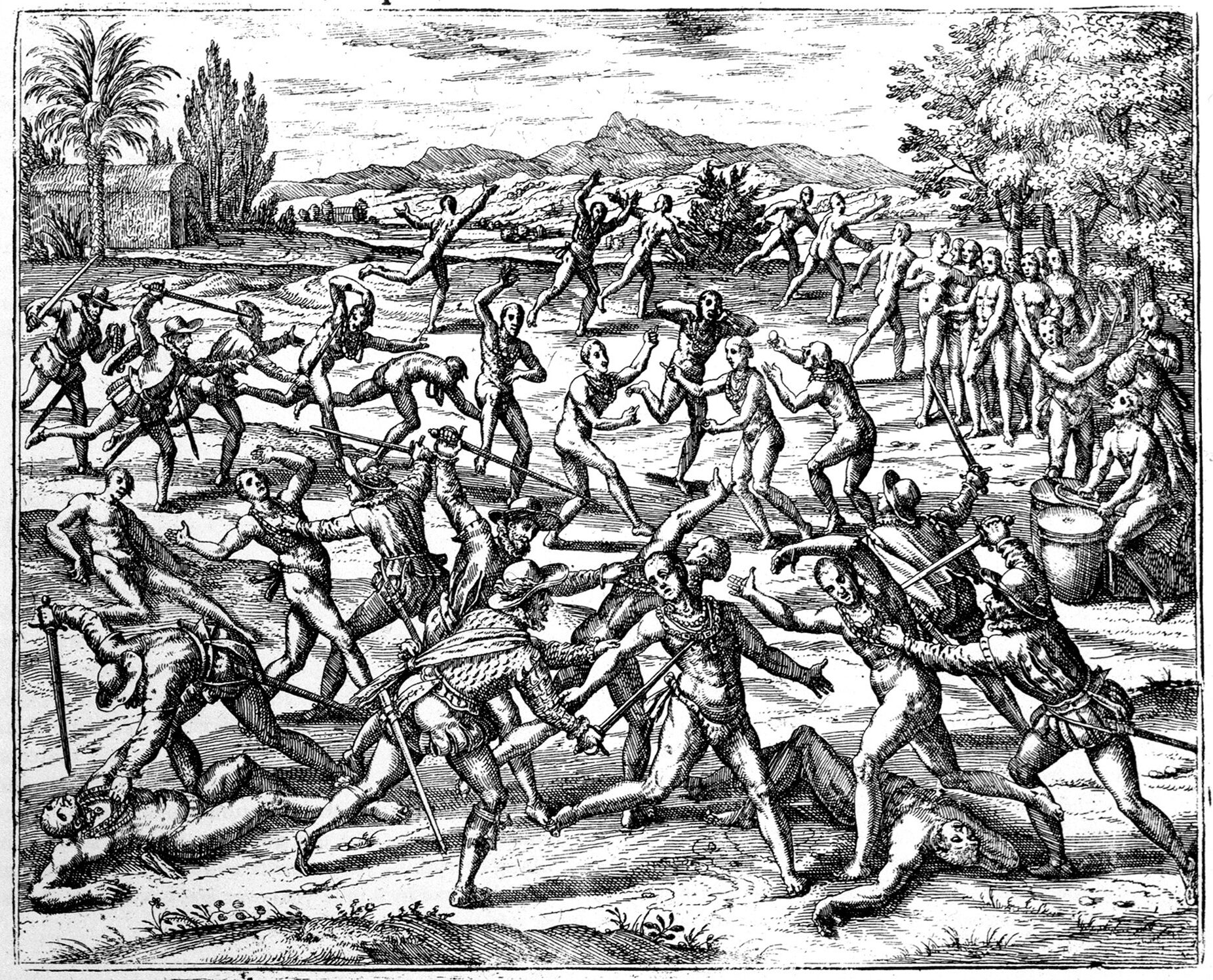

When Cortés led his mounted lancers in a spirited charge against the Aztec line, he found that the Aztecs had fashioned new weapons. Using Spanish steel salvaged from Lake Texcoco after La Noche Triste, they had cleverly fashioned deadly polearms.

“In the narrow space of the causeway, the Aztec received the charge of the cavalry with fixed lances, and wounded four of our horses,” wrote conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo. “Cortés’ mount fell down with its rider, and numbers of Aztecs instantly laid hold of our general, tore him away from the saddle, and were already carrying him off when Cristobal de Olea and some Tlaxcala flew to his assistance, and, by dint of heavy blows and good thrusts were able to free their comrade.”

Although Cortés managed to escape, several Spaniards were captured. They were taken before Cuauhtémoc, who ordered them to be sacrificed. The Aztecs dispersed their severed limbs throughout their empire as a warning to wavering tributaries.

From high atop the pyramid of Xochimilco at dawn the following day, Cortés and his captains could see thousands of Aztec warriors in canoes paddling furiously toward them. The force, which was estimated at 15,000, shouted battle cries that echoed across the lake. At least 10,000 more were on the march from Tenochtitlán. The Spaniards and their allies soon came under attack from both land and sea. Aware that he did not have sufficient forces to hold the city, Cortés ordered a withdrawal. The Spaniards and their allies then marched back to Texcoco.

When he reached Texcoco, Cortés heard the news that he had awaited: His shipbuilders had completed the construction of the 13 brigantines. The Spanish launched the vessels on Lake Texcoco on April 28, 1521.

For his first combined land and naval assault on Tenochtitlán, Cortés had at his disposal 700 infantry, 86 horsemen, and 118 crossbowmen and arquebusiers. The army had substantial artillery in the form of three heavy iron guns and fifteen 3-pounder falconets.

Cortés’ native troops, who were motivated by the desire for revenge, greed, and fear of Spanish reprisal, numbered 200,000 warriors. Most of these warriors hailed from the cities of Tlaxcala, Texcoco, Cholula, Chalco, and Huexotzinco. The chief of the Totonacs provided 50 warriors and 400 porters, the latter to help transport Cortés’ falconets. Cortés was about to draw on two centuries of European siegecraft to target the city’s food and water supplies and sanitation system.

Cortés had three infantry divisions commanded by captains Pedro de Alvarado, Christobal de Olid, and Gonzalo de Sandoval. By mid-May 1521, the three divisions were in position to invest Tenochtitlán. Cortés gave each captain two cannon, retaining the remainder for his use. Alvarado and Olid departed Texcoco on May 22, marching around the northern shore of the lake to approach Tenochtitlán from the west. Sandoval set out nine days later, marching along the eastern side of the lake to approach Tenochtitlán from the south.

Alvarado reached Tacuba with 150 Spanish infantry, 30 horsemen, 18 crossbowmen and arquebusiers, as well as 50,000 indigenous allies drawn mostly from Tlaxcala, Texcoco, and Otumba.

Olid accompanied Alvarado to Tacuba, and then pressed further on to Coyocán. He had a force of 38 horsemen, 20 crossbowmen and arquebusiers, and 150 Spanish pikemen. He also had 50,000 native warriors drawn from Tziuhcohuac and various other northern provinces.

As for Sandoval, he had under his command 23 horsemen, 14 arquebusiers, 13 crossbowmen, and 170 Spanish pikemen. He struck out for Iztlapalapa accompanied by 40,000 assorted allies from Chalco, Cuernavaca, and other southern cities.

Cortés took personal command of the naval squadron that would crew the 13 brigantines. Each sloop had a crew of 25 that consisted of a captain, six crossbowmen, six arquebusiers, and 12 oarsmen. The ever-loyal Ixtilxochitl commanded a flotilla of Texcoca war canoes that would escort Cortés’ fleet.

The fourth major causeway, which ran north to Tepeyacac, was deliberately left open. Cortés hoped to tempt Cuauhtémoc to make a sortie from the city onto open ground, where Spanish mobility would prove decisive. Although the emperor refused to take the bait, he could not stop Alvarado from occupying Tacuba on May 25.

The following day, Alvarado and Olid combined their forces and launched a combined-arms attack against Chapultepec. Although the country was not ideal for mounted warfare, the two captains resolutely broke through the Aztec defenses and destroyed the city’s aqueduct. This deprived the townspeople of fresh water for the remaining 75 days of siege. Sandoval inflicted yet another crippling blow to the Aztecs by capturing the strategic city of Iztapalapa on May 31.

The Spaniards were shocked by the urban battles they had to fight and the sheer number of enraged native warriors they faced. Veterans of Spain’s wars against its European foes, such as the Ottoman Turks, said they had never seen such bravery in all the fighting they had done in the Mediterranean theater.

Forced to fight in the back alleys and narrow corridors of Tenochtitlán, the Spanish found themselves under constant missile attack from the surrounding rooftops. Their cannon saved the day, for the grapeshot shredded wave after wave of attackers. In addition, repeated charges by the lance-wielding horsemen, as well as steady volleys of crossbows and arquebus fire, cut the natives down from distances of 100 yards or more.

While his three captains advanced along the Tacuba, Tepecayac, and Iztapalapa causeways the next morning, Cortés led his brigantines into the fray aboard his flagship, the Capitana. The Aztecs succeeded in forcing him to divert from sailing straight to Iztapalapa, where he intended to support Sandoval. After he spotted enemy lookouts sending smoke signals to Tenochtitlán from the small island city of Tepepolco, Cortés landed on the island with 150 men, overran its fortifications, and killed all of its defenders.

Setting off once again from Tepepolco, Cortés’ fleet clashed with a fleet of 600 Aztec war canoes, many of which had been outfitted with additional wooden shielding that offered the crews more protection. As the Spanish brigantines glided swiftly through the water, ramming and blasting their way through the enemy flotilla, the Aztec missiles fell harmlessly against their sturdy sides. The combination of oar-power and sail-power meant the Spaniards’ brigantines could outmaneuver the Aztec war crews. What is more, the high decks made it nearly impossible for the Aztecs to successfully grapple and board the brigantines. All the while, the Spanish crossbowmen and arquebusiers could fire down on the Aztecs, inflicting heavy casualties on them.

The Texcocan canoes coming up in support vanquished any Aztec canoes that remained in Cortés’ wake. Once the Aztec war canoes had been vanquished, Cortés sailed on and seized the fortress at Xoloc on the main causeway from Iztapalapa to Tenochtitlán. This enabled Olid, whose flanks were protected by the brigantines, to link up with Cortés.

The Aztecs nearly had an important success on June 1, when the captain of the Capitana, Rodriguez de Villafuerte, inadvertently ran the vessel aground in the shallows. After a host of enemy warriors swarmed aboard, Villafuerte gave the order to abandon ship and fled to the rear of the sloop, where he might leap across to another brigantine nearby with Cortés at his side.

Marin Lopez, the man who had labored around the clock to construct and transport the fleet, refused to give up so easily, and he rallied its crew. Observing an Aztec officer in feathers and plumes directing the assault from a nearby canoe, Lopez picked up a crossbow and shot the man dead.

The Spanish repulsed the boarders, which left the deck littered with dead and dying. Despite a determined defense by the Aztecs, who had lined their canals with sharpened stakes and had succeeded in destroying two brigantines, the Spaniards prevailed. With his brigantines, Cortés had smashed the Aztec navy.

Having mobilized all available manpower, Cuauthémoc divided his forces into four divisions. The first division covered the northern causeway to Tepeyacac; the second division defended the Tacuba Causeway against Alvarado; the third division concentrated against Cortés Olid, and Sandoval at Acachinanco; and the fourth division took up a reserve position to contest possible amphibious landings in other parts of the city. The battle for the causeways now began in earnest.

From that point forward, Cortés adopted a policy of total warfare, “I saw how determined to die in their defense, they gave us cause, and indeed obliged us to destroy them utterly,” he said. With Tenochtitlán effectively surrounded, Cortés personally led Olid’s division in a major assault against the city on June 10, with Alvarado and Sandoval advancing along the Tacuba and Tepeyacac causeways, respectively.

Using his brigantines as pontoons to bridge gaps in the Iztapalapa Causeway, Cortés overran the defenses at the Eagle Gate, the southern entrance to the city, and advanced as far as the Temple Compound. After heavy fighting raged all day, the three Spanish divisions withdrew with some difficulty. They tore down temples, walls, and homes as they fell back.

Meanwhile, the brigantines enforced a tight blockade of the city. They intercepted Aztec canoes conducting supply runs and blasted the city’s walls with their cannons. Growing ever more confident, Cortés and his captains launched daily forays into Tenochtitlán. During these incursions they nearly always advanced as far as the temple complex before withdrawing. As they withdrew, they left a trail of destruction in their wake.

Cortés spent the nights at his headquarters in Xoloc. Every incremental gain achieved by the Spaniards was exploited by their allies, whose numbers were increasing almost daily. They knocked down houses to remove platforms for missile troops and used the rubble to fill in canals and breaches in the causeways. This made it easier for them on successive attacks and enabled them to penetrate deep into the dying city.

The shifting tides of war eventually turned for a time in favor of the Aztecs. With his defenses crumbling and with scant options available, Cuauhtémoc radically changed his tactics in mid-June by removing almost all of Tenochtitlán’s remaining populace to its sister city to the north, Tlatelolco, a move the Spaniards wrongly perceived to be a retreat. At the head of his cavalry division, the rash Alvarado on June 23 was lured into Tlatelolco by a feigned Aztec retreat across a narrow breach in the causeway. Leaving his infantry behind, Alvarado and his horsemen rushed across the canal, only to be ambushed by overwhelming numbers of Aztecs.

With the breach they had crossed blocked by hundreds of canoes, the attackers were fortunate to escape. Alvarado and eight others were wounded, and five Spaniards were captured and taken to the Great Temple to be sacrificed. This gave the city’s defenders a much-needed victory. Despite the hardships they had endured, the inhabitants of Tlatelolco remained loyal to Tenochtitlan through her darkest days. In the siege’s final days, it became the last redoubt for resistance against the allies.

Catastrophe found Cortés, as well. Persuaded to launch a premature attack against Tlatelolco, Cortés ordered a large-scale assault on June 30 that he hoped would end the siege in a single stroke. Sandoval and Alvarado, backed by six brigantines and 3,000 allied war canoes, attacked the city from the west along the Tacuba Causeway. After Cortés entered the city from the south, he divided his force into three columns, each with about 100 Spaniards, eight horsemen, and tens of thousands of allied warriors, sappers, and porters. Working in concert with each other, they would force their way along the roads from Tenochtitlán to Tlatelolco.

At first, all went well. The Allies “fought their way into the city, killing many and taking houses, bridges, and fortifications without sparing anyone, in such a way it seemed they would take Mexico that day,” recalled Ixtilxochitl. Aztec resistance then stiffened, though, as the Allies advanced deeper and deeper into unfamiliar and irregular city blocks. Cortés was unhorsed again and almost carried off before he was rescued. The enemy’s preference for taking captives instead of killing the foe once again saved Cortés’ life.

Under a deluge of arrows, stones, iron-tipped spears, and piercing darts that rained down on all sides, the three assault columns stalled in the face of massive numbers. As they withdrew, their retrograde movement quickly turned into a rout. With a total collapse in progress, Cortés ordered all units to pull out of the city back to the relative safety of their compounds. Dozens of Spaniards and Tlaxcalans had been slain. Cortés lost one cannon, a brigantine, and eight horses. In addition, the Aztecs captured 50 Spaniards and 100 Tlaxcalans.

After they witnessed captured Spaniards and Tlaxcalans being herded naked up the steep slopes of the Great Pyramid and slaughtered in a gruesome public spectacle, Cortés’ massive army of indigenous allies vanished. “One by one they were forced to climb up to the temple platform, where they were sacrificed by the priests,” said a native who witnessed the scene. “The Spaniards went first, followed by their allies, all were put to death. The Aztecs ranged the Spaniards’ heads in rows on pikes, arranged so their faces were toward the sun.”

Elated by their victory, the Aztecs went on the offensive the next morning, launching wave after wave of foot and canoe attacks on each of the Spanish compounds. Most of Cortés’ allies from Cholula, Huexotzinco, Chalco, Texcoco, even Tlaxcala, had returned home, leaving token forces behind. While Cortés regrouped and his men recovered from their wounds, Cuauhtémoc rallied his allies, sought new support, and sent the severed body parts of slain Spaniards to the cities surrounding the lake as proof the invaders were not invincible.

Adding to Cortés’ woes, envoys from cities that had accepted Spanish suzerainty began arriving at Xoloc, pleading for protection from tribes stirred up by Cuauhtémoc. In the supreme crisis of the siege, Cortés rose to the challenge, dispatching sufficient forces under Sandoval and Diego Tapia to aid Cuernavaca and Toluca, allies who were being threatened. Cortés’ huge gamble paid off. The Spaniards’ total victories in both actions stabilized the diplomatic situation and proved that Cortés army had lost none of its prowess in battle. What is more, it proved that the Spanish would readily come to the aid of their indigenous allies. The Allied units that had vanished en masse just days earlier now flocked back to Cortés’ banner.

Fortunately for Cortés and his withering army, the Aztecs did not mount any serious attacks against the Spanish camps for most of July 1521. Their defense of the city was clearly faltering. Disease, starvation, battle casualties, and the destruction of much of their city from the fighting in late June had greatly diminished and demoralized the remaining defenders. Aztec accounts describe people reduced to eating lizards, corn cobs, weeds, leather, and even dirt. “Nothing can compare with the horrors of that siege and the agonies of the starving,” stated one account. With the Aztecs’ strength waning, Cortés went on the offensive.

Allied columns cleared the entire Tacuba Causeway on July 21. In so doing, they linked the western (Alvarado) and southern (Cortés and Olid) columns. Four days later, all three Allied divisions advanced to the great marketplace in Tlatelolco, where the emperor had chosen to make a last stand. They stormed the Great Pyramid, torched the temple at its summit, and planted Cortés’ banner atop it.

The next day, Cortés climbed to the summit of the pyramid once more, from where he could confirm that most of the city was under Allied occupation. Supplies from Vera Cruz continued to arrive unmolested, and Aztec deserters told Cortés the inhabitants of both island cities were starving, and the emperor had begun conscripting women to fill his ranks.

Spanish lancers freely roamed the causeways by August 1521, wiping out any natives who dared leave their homes in search of food. Cortés’ vengeful Tlaxcalan allies roamed the city slaughtering, and sometimes eating, their hated foes. In this way, they gained revenge for generations of enforced isolation and tribute. With no surrender from the emperor forthcoming, Cortés resumed hostilities on August 12.

The last remaining body of Aztecs, packed into the small pocket of the city they still possessed, was finally overrun. “We jostled and crowded against one another, but no one could go anywhere,” stated an Aztec account. “Many, in fact, died trampled in the press. Any Aztec survivors now fled the city, leaving behind houses crammed with dead bodies, and among them several poor people were found still alive, too weak to stand, and lying in their own filth.”

After courageously directing the capital’s defenses for three months and gaining the admiration of his enemies, Cuauthémoc was captured on August 13, 1521, attempting to flee the city in a canoe. He was brought before Cortés and signed a formal surrender, at which moment the siege ended and the Aztec Empire ceased to exist, replaced by what the invaders were by then calling New Spain. Cortés tortured the emperor in a futile attempt to acquire gold and forced him to play the role of puppet ruler. He took him on a failed expedition to Honduras, and ultimately executed him on false charges in 1523.

The fabulous city that had greeted Cortés two years earlier was now a wasteland. During the course of the long siege of the city that began in late May, 100,000 Aztecs had fallen in the fighting. The Spanish had lost 100 conquistadors, and their allies lost upwards of 70,000 men.

Of the 1,800 conquistadors who campaigned in Mesoamerica between 1519 and 1521, approximately 1,000 had been killed in battle or captured and sacrificed to the Aztec gods. Disease, famine, and constant warfare had effectively wiped out Tenochtitlán’s population. Even in their death throes, the Aztecs had taken a fearsome toll upon Cortés’ allies. Their archenemies, the Tlaxcalans, lost 30,000 fighters.

Far from benefitting from their association with Cortés, his native allies eventually found that they had exchanged the threat of subordination to Tenochtitlán for the reality of subordination to Spain. Cortés and Spain’s alliance with Xicotencatl the Elder, which had saved the Spaniards when they were at their weakest and most vulnerable, was soon discarded by Madrid, thus reneging on the terms of their agreement to aid Tlaxcala in imposing regional hegemony.

The only real victors to emerge from Cortés’ conquest, which in two years changed the face of an entire subcontinent, were the Spanish Crown and the Roman Catholic Church, which obtained a secure foothold in the Americas from which they could expand their imperial presence in the New World.

Oddly enough, Cortés’ name is rarely mentioned among the great captains of history. Yet his two-year odyssey into the Valley of Mexico, which culminated in the destruction of the great city of Tenochtitlán and the Aztec Empire, has to be considered one of the most extraordinary military campaigns ever waged. With no military experience, no formal authority, no intelligence regarding his expected theater of operations, and only a handful of men, he forged a multinational coalition that brought down an empire and reshaped an entire subcontinent.

With the conquistador era and its four decades of unrestrained greed, barbarity, and cruelty drawing to a close, the man who has conquered the vast Aztec lands so that they could be incorporated into the colony of New Spain was marginalized and almost forgotten.

His followers, though, appreciated the scale of his conquests and paid tribute to him.

“Long live, then, the name and memory of him who conquered so vast a land, converted such a multitude of men, cast down so many idols, and put an end to so much sacrifice and the eating of human flesh,” wrote Francis Lopez in 1552, of Cortés’ military achievements.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments