By Mike Phifer

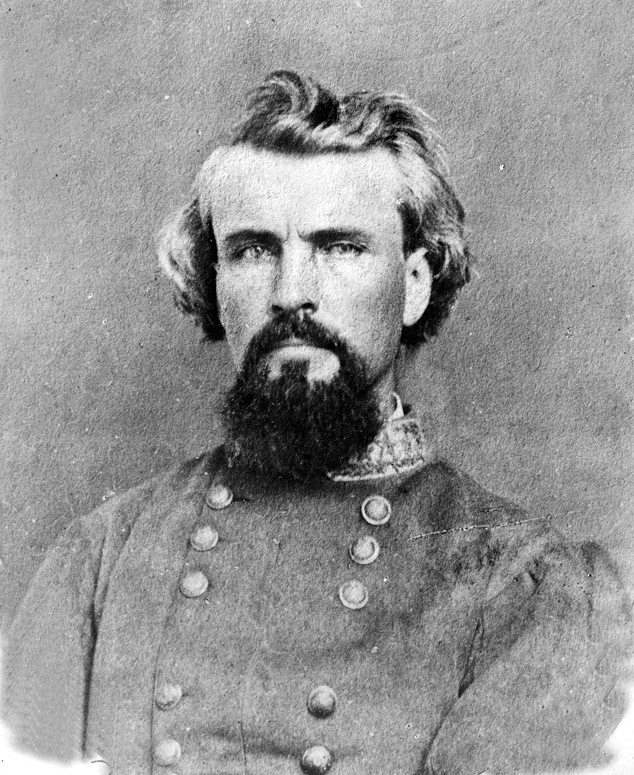

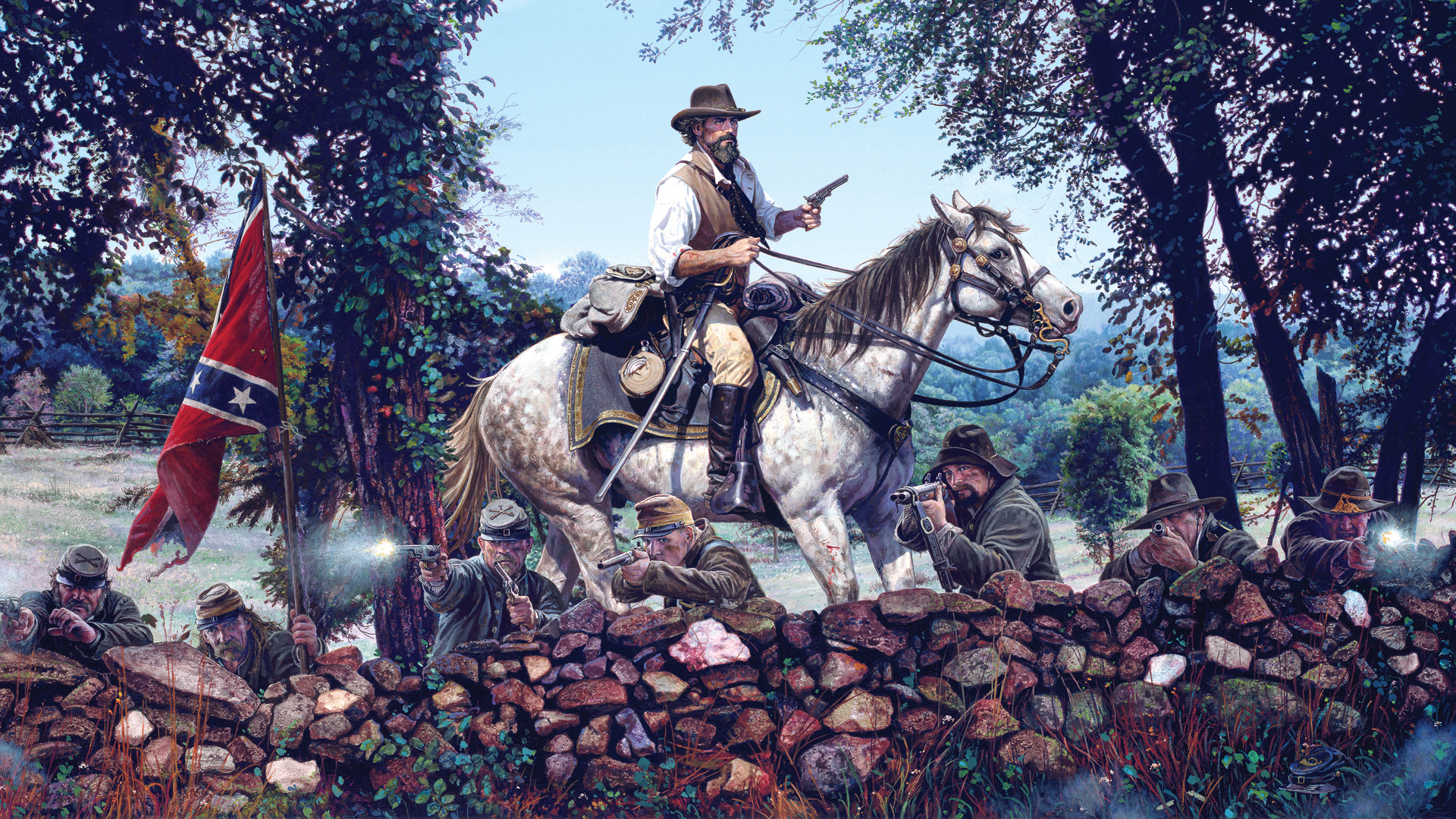

Confederate Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s fighting blood was up. It was mid-morning on June 10, 1864, and the Tennessean cavalry commander had just hurried Colonel Hylan Lyon’s brigade of Kentuckians from along the muddy Baldwyn road toward Brice’s Crossroads in northern Mississippi. Forrest’s route crossed the Ripley-Guntown Road, where William’s Brice two-storey white house, general store, and a few outbuildings were situated. It was not the buildings that interested Forrest, but the Yankee cavalry brigade posted just east of the crossroads. Another Union cavalry brigade lurked nearby.

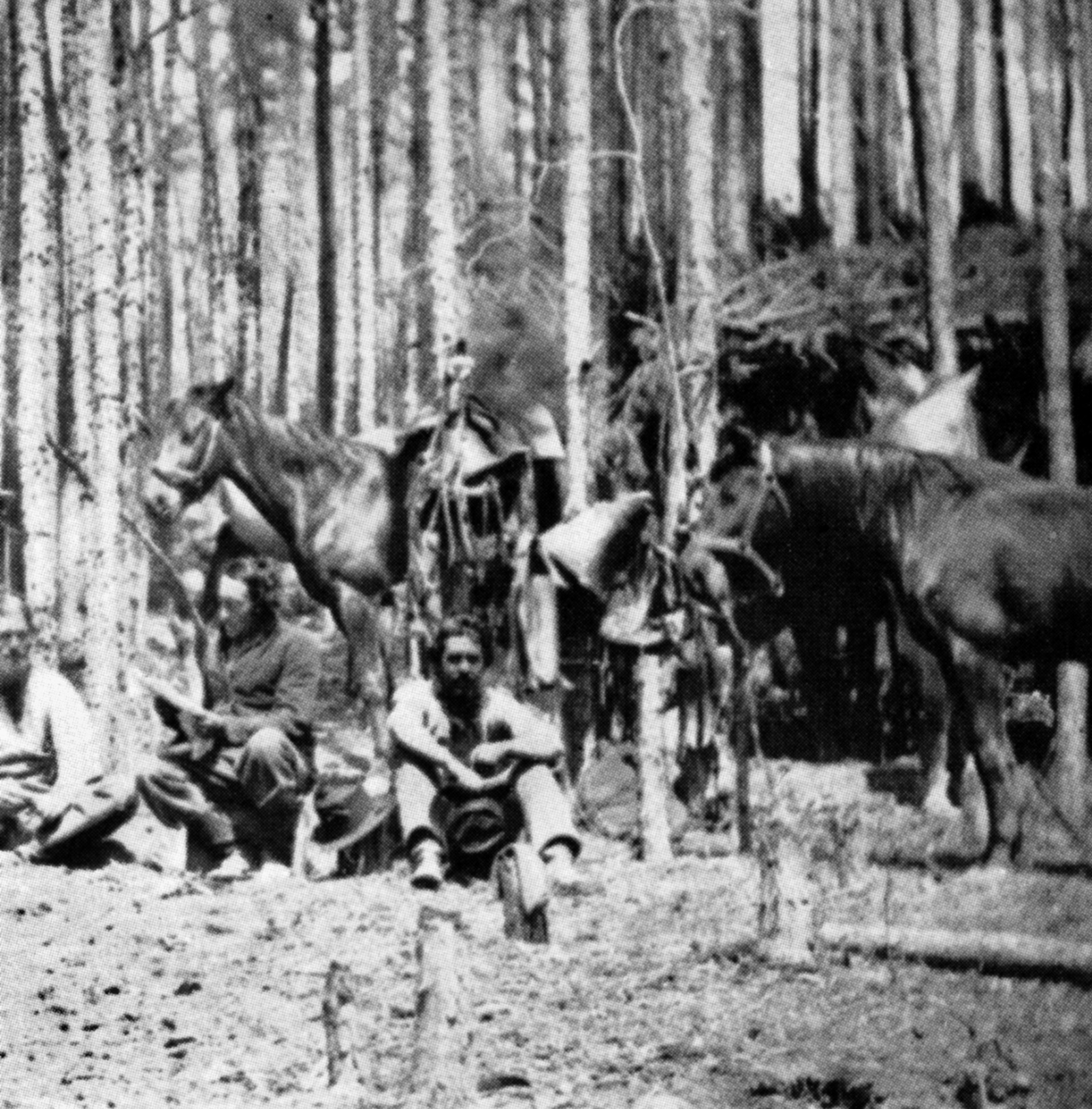

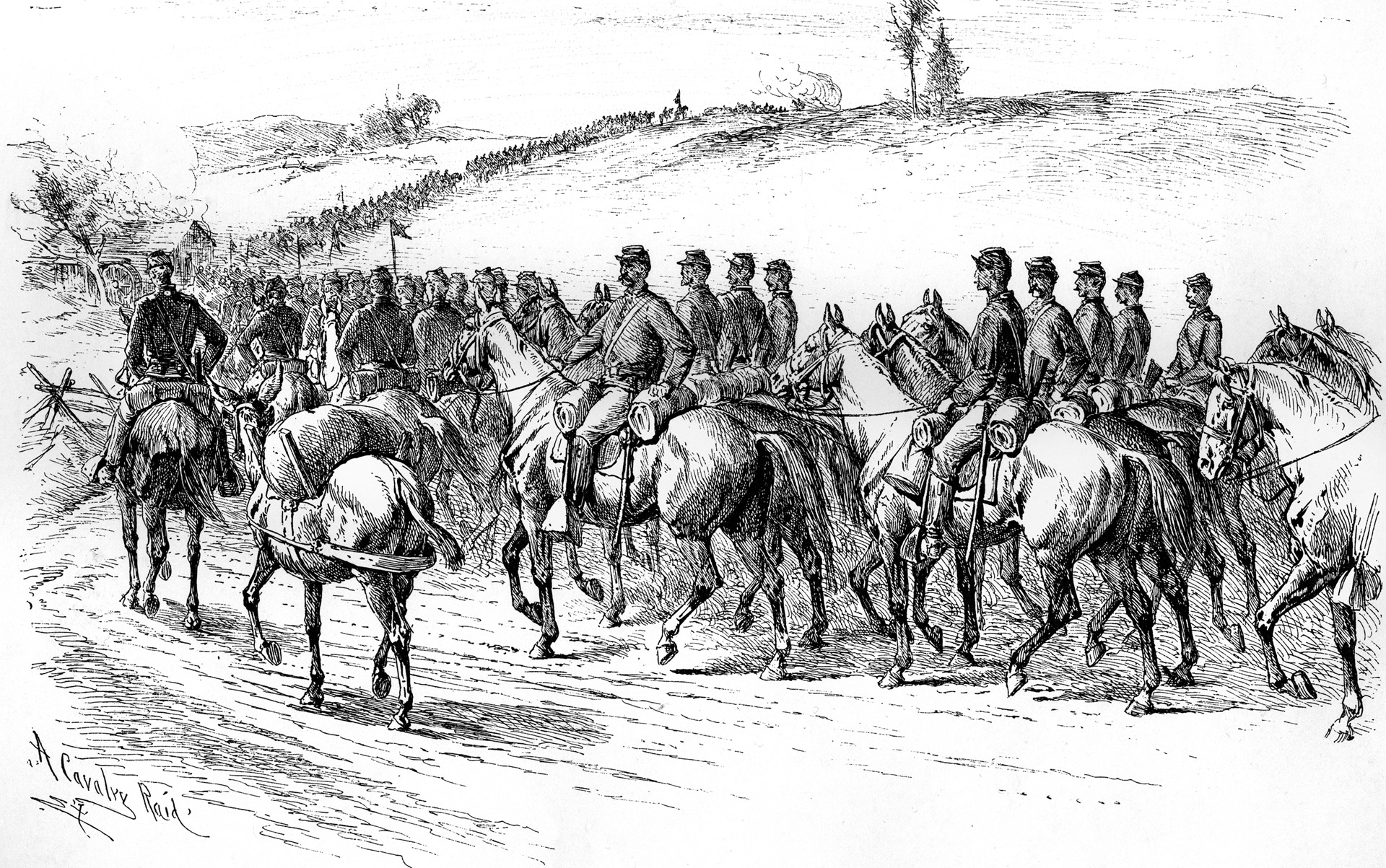

A few companies of Forrest’s regiments had already skirmished with the Federals, determining their strength. Although outnumbered, Forrest meant to gain and hold the initiative by launching an attack. He ordered Lyon to dismount his 800 Kentuckians and advance on both sides of the Baldwyn road. As was typical on both sides when cavalry fought dismounted, one man held the reins of four horses while the other three went into action in foot.

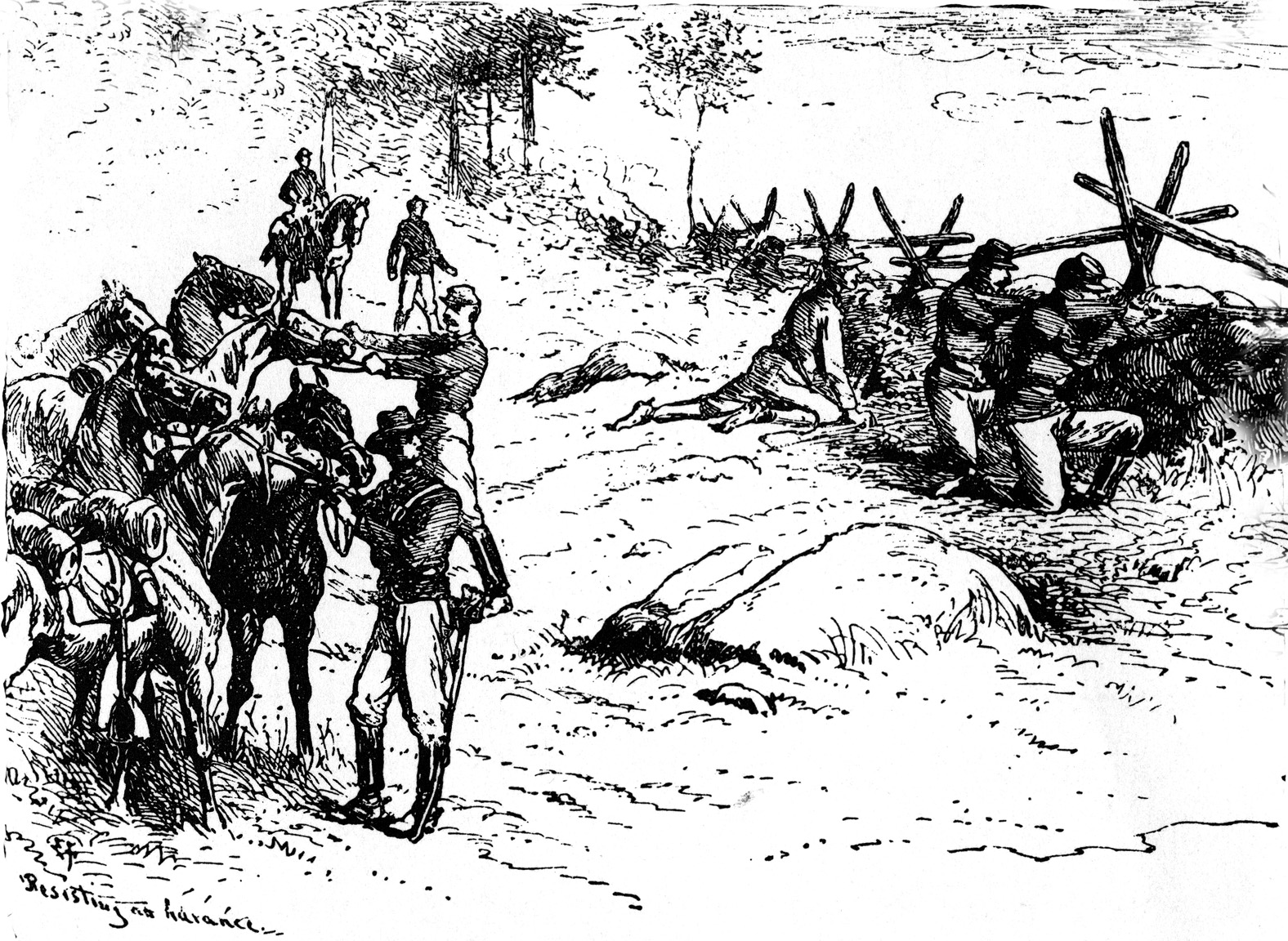

Moving quickly through the undergrowth that camouflaged them, Lyon’s Kentuckians launched a spirited attack against Colonel George Waring’s cavalry. The crack of carbine fire reverberated as the Confederates forced back the Federal cavalry. Lyon’s men seized a ridge from which to fire on the Yankees. When they saw the Federal cavalry massing in their front, the Confederates hurriedly began building a breastwork of logs and fence rails.

Colonel Edmund Rucker rode up with his 700 men. Forrest ordered them to dismount and take up position on Lyon’s left flank. Arriving a little later was Colonel William Johnson’s brigade of 500 Alabamians, who would form on Lyon’s right. Although they were still outnumbered, the Confederate troopers boldly engaged the dismounted Federal cavalrymen, who were armed with rapid-firing carbines.

Forrest needed to buy precious time until the other half of his command arrived from nearby towns. When they did, Forrest intended to press his attack against the mixed force of Federal cavalry and infantry at Brice’s Crossroads. He intended to drive off the Union cavalry first, and then fall on the blue-coated infantry marching to their aid.

The battle came about because Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, the commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, was worried in spring 1864 about his supply line through middle Tennessee. Three armies under his overall command were advancing on Chattanooga into north Georgia with the aim of capturing Atlanta, one of the most important railroad hubs in the Confederacy.

President Abraham Lincoln had created the Military Division of the Mississippi as a way to improve the organization of U.S. forces in the western theater in the wake of the Union defeat at Chickamauga in September 1863. When Grant was promoted to lieutenant general on March 10, 1864, and given command of all U.S. forces arrayed against the Confederacy, Grant picked Sherman to succeed him as commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi.

To keep his 100,000 troops in the Armies of the Cumberland, Ohio, and Tennessee supplied, Sherman had to rely on the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad that connected his army with the sprawling supply depot in the Tennessee state capital. Protecting his line of supply through middle Tennessee would require a considerable allocation of manpower. “Every foot of the way, especially the many bridges, trestles, and culverts, had to be strongly guarded against the acts of a local hostile population and of the enemy’s cavalry,” said Sherman. Although there were other Confederate cavalry commanders operating in the western theater, Sherman was most concerned about Forrest.

Having enlisted at the beginning of the war as a private, Forrest had risen to the rank of major general despite never having had any formal military training. His success was a direct result of his bravery, sharp wits, and fierceness in battle.

Fearing that Forrest would cut the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, Sherman directed Maj. Gen. Cadwalader Washburn in late May to send a mixed force of cavalry and infantry and defeat Forrest. “I know that there are troops enough at Memphis to [whip] Forrest if you can reach him,” Sherman told Maj. Gen. Cadwalader Washburn, the newly appointed commander of the District of Western Tennessee, whose headquarters was in Memphis.

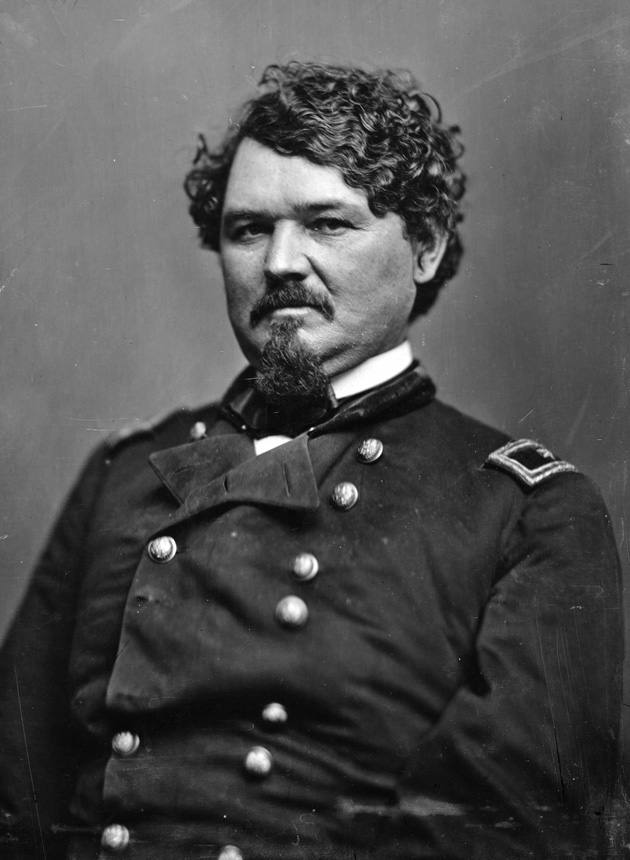

Washburn picked Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis for the expedition to defeat Forrest. Reaching Forrest proved difficult enough for Sturgis, who had commanded troops in a half-dozen significant engagements. His force consisted of 8,300 cavalry and infantry, as well as 22 field guns and mountain howitzers. In addition, the expedition possessed 250 wagons that hauled enough food and ammunition to keep the army supplied for three weeks. The troops were organized into two divisions. Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson led a division of 3,300 cavalrymen, while Colonel William McMillen led a division of 5,000 infantrymen.

Grierson’s division consisted of Colonel George Waring’s First Brigade and Colonel Edward Winslow’s Second Brigade. As for McMillen, he commanded three infantry brigades: Colonel Alexander Wilkin’s First Brigade, Colonel George Hoge’s Second Brigade, and Colonel Edward Bouton’s Third Brigade.

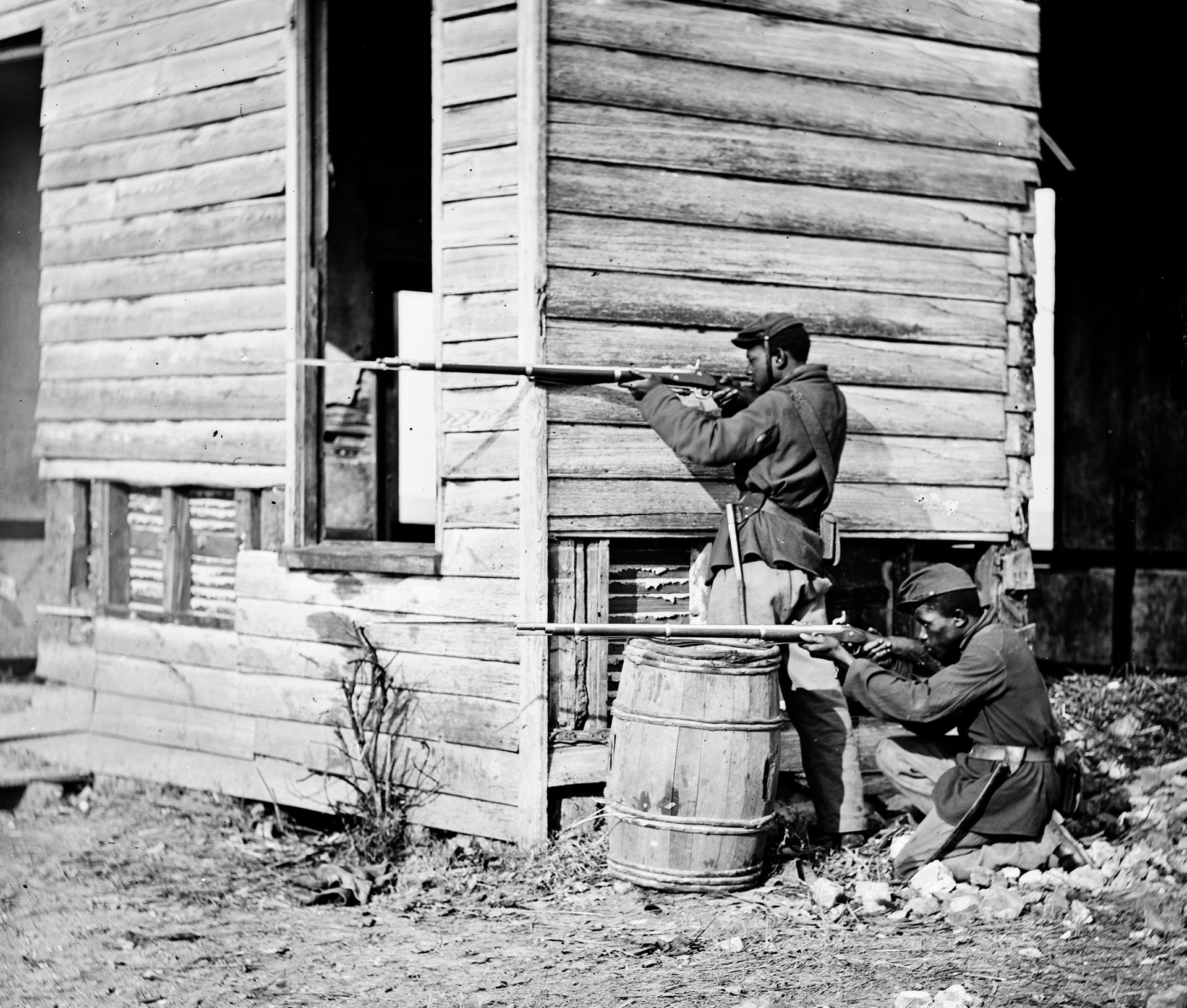

The Third Brigade consisted of the 55th and 59th U.S. Colored Troops. The soldiers in these two regiments were determined to exact revenge against Forrest for the massacre on his watch of several dozen black soldiers in mid-April after they had surrendered at Fort Pillow.

Sturgis had orders from Washburn to strike for Corinth, Mississippi, and destroy any supplies there. From there he was to push south along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad to Tupelo, wrecking the railroad as he did. Sturgis was then to continue on to Okolona, Mississippi, wrecking more railroad tracks. He was then to move on to Grenada before returning to Memphis. “This is a general outline, the whereabouts of Forrest will, of course, have much to do in regulating your movements,” said Washburn.

Sturgis’ command departed Memphis on June 1. Almost immediately, a steady rain began to fall. Sturgis’s infantry boarded train cars to journey southeast along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad towards Lafayette, Tennessee, on the Mississippi border. The cavalry, artillery, and wagons travelled by road. Five miles from Lafayette, the troops unloaded and set out on foot for the burned-out town as heavy showers began to pelt them. More troops continued to arrive by train the following day, as did Sturgis, after a night of hard drinking in Memphis.

That same day, Forrest departed Tupelo, Mississippi, bound for Middle Tennessee. His command consisted of 3,500 troopers. Forrest had orders to tear up track on the Chattanooga & Nashville Railroad. While en route through northern Alabama, he received an urgent dispatch from Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, who commanded the Department of Mississippi and West Tennessee, instructing him to return immediately to Tupelo to intercept a Federal column that Lee feared was headed to south central Alabama to destroy that state’s agriculture and industrial resources.

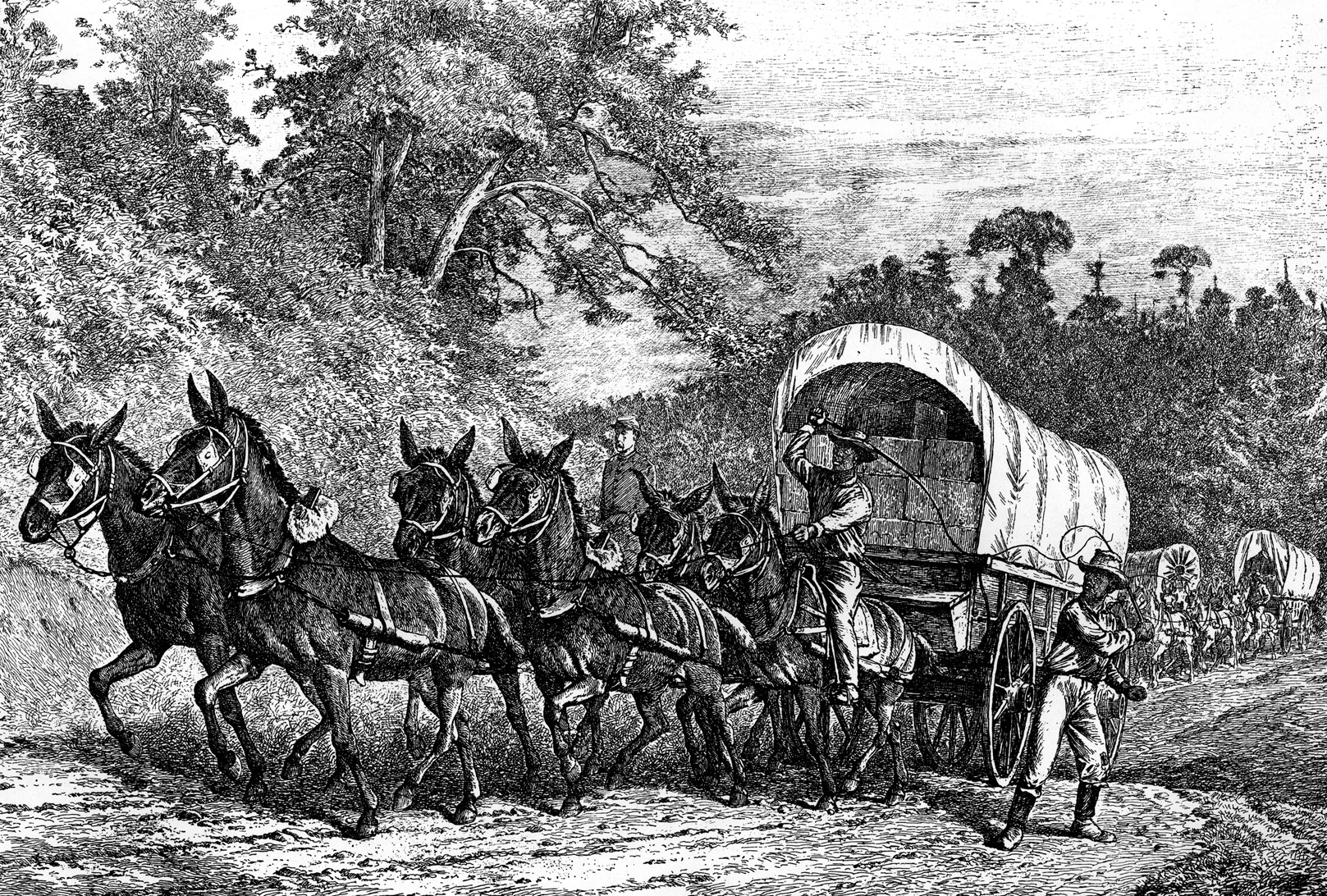

The rain continued to fall on June 3 as the Federals marched southeast along roads awash with mud through dense forest. The Third Brigade in the rear was tasked with guarding the long wagon train. Progress was slow because of the muddy roads. McMillen ordered a detachment of pioneers, which was drawn from the 9th Minnesota, to fell timber and construct corduroy roads in an attempt to aid the struggling teamsters of the wagon train. Its efforts were of little use. “The rain fell in torrents, and morning found the roads impassable ahead,” recalled Sergeant John Merrilies of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery.

When the rain let up temporarily on June 6, the humidity and heat quickly became unbearable. Several mules and horses struggling to pull the wagons along the muddy roads collapsed with heatstroke. Adding to the animals’ misery was the lack of feed for them. Sturgis had hoped that by foraging, his men could feed the animals, but it proved to be an unrealistic expectation. “The line of march was through a country devastated by the war, and containing little or no forage, rendering it extremely difficult, and for the greater portion of the time impossible, to maintain the animals in a serviceable condition,” noted McMillen.

That night the First Brigade bivouacked six miles from Ruckersville, Mississippi. Grierson’s cavalry waited at that location for the slow-moving infantry to catch up. The commander of the Union cavalry sent patrols in the direction of Corinth in an effort to locate Confederate forces, but they had withdrawn south.

When Grierson informed Sturgis of the absence of Confederate forces, he decided to march southeast to Ripley, Mississippi. On the morning of June 7, the Union cavalry reached Ripley. Grierson sent the 4th Iowa Cavalry to reconnoiter beyond the town. The Iowans ran headlong into a Rebel skirmish line strengthened by two guns positioned on a hill. To assist the hard-pressed Hawkeyes, Grierson sent the 7th Indiana Cavalry. The troopers dismounted and advanced, only to find the Confederates had once again withdrawn.

By this time, Sturgis was at Ripley and was beginning to have doubts about continuing the expedition. “The rain still fell in torrents,” said Sturgis. “The artillery and wagons were literally mired down, and the starved and exhausted animals could with difficulty drag them along.” He conferred with his division commanders to discuss the situation. Sturgis feared that with their advance slowing down, the enemy might concentrate a superior force in the vicinity of Tupelo. If they were defeated in battle, Sturgis thought it was highly likely they would also lose their wagons and artillery to the Confederates owing to the deplorable conditions of the muddy roads.

For his part, Grierson wanted to return to Memphis. He argued that to proceed further would be to invite disaster. If they continued on, he said, then the rations should be distributed to the troops and the wagons sent back to Memphis.

For his part, McMillen believed the expedition should continue with the wagon train until the enemy was found and engaged. “If we went back without a fight, we would be disgraced,” he said. After listening to both views, Sturgis decided the expedition would continue even though the rain continued to fall hard.

The weather was again distressingly hot and humid on June 8. At that point, Sturgis put 400 sick soldiers in 41 empty wagons and sent them back to Memphis.

The Federals continued marching southeast the following day along the Ripley-Guntown Road. Fourteen miles beyond Ripley, the troops halted for the night near Thomas Stubbs’ farm. The unrelenting rain continued to make things miserable for the troops.

While the Federals pushed deeper into Mississippi, Forrest rode into Tupelo on June 6 from an aborted middle-Tennessee raid. Learning of Sturgis’ whereabouts, Forrest dispatched scouts to watch him. He also began to consolidate his far-flung command. Forrest’s Cavalry Corps was composed of the divisions of Brig. Gen. James Chalmers and Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford. Chalmers’ division was composed of three brigades under Colonels Robert McCulloch, J.J. Neely, and Edmund Rucker. Buford’s division consisted of two brigades led by Brig. Gen. Tyree Bell and Lyon. Colonel Johnson’s small brigade from Colonel P.D. Roddey’s command was unattached. In addition, Forrest had four batteries consisting of four guns each, under the overall command of Captain John Morton.

Neither Lee nor Forrest was sure of Sturgis’ intentions. They supposed that Sturgis might want to destroy Forrest, burn the farms in northern Mississippi, or even march east via Corinth to join Sherman in north Georgia. Both Confederate commanders began to assemble troops to block either move. Forrest set out for Booneville, Mississippi; Rucker’s brigade arrived at Booneville on June 9.

Lee told Forrest that he believed Sturgis was headed deeper into Mississippi. Lee set off by train for Okolona with two batteries of artillery to gather more troops to face the Yankees. Forrest was to follow the next day, but Lee gave him the discretion to act otherwise depending on the Federal army’s movement.

That evening, Forrest called a council of war. Having learned that Sturgis was at Stubbs Farm, the Confederate commander concentrated his forces on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad to contest a Federal advance on either Corinth or Tupelo.

When Forrest learned on June 8 that Sturgis was advancing on Tupelo, he selected a site to engage Sturgis’ force. The site he selected was the intersection of two dirt roads known to locals at Brice’s Crossroads. The crossroads received its name because the Brice’s house stood at one corner of the dirt road intersection and his store was situated on another corner.

Forrest estimated that Sturgis had upwards of 10,000 men. The odds in a pitched battle would seem to heavily favor Sturgis, given that half of Forrest’s force was 25 miles away at Rienzi, Mississippi. Although the battle would be a gamble given that he was seemingly heavily outnumbered, Forrest hoped to even the odds by attacking the Federals on the ground of his choosing. He was regarded throughout the South as the “Wizard of the Saddle,” and he intended to further enhance his sterling reputation.

Forrest knew that Grierson’s cavalry would compose the vanguard. He expected the Federal troopers to arrive at the crossroads several hours ahead of the Federal infantry. He knew that Sturgis would have to have his infantry march at the double-quick to reach the battlefield. “We can whip their cavalry in that time,” Forrest said. “It is going to be hot as hell, and they will be coming on a run for five or six miles over such roads, their infantry will be so tired out we will ride right over them.” After sharing his plan for the battle, Forrest rode ahead with Lyon’s brigade to attack the Federal cavalry.

The Federal troopers at Stubbs Farm also saddled up early in the morning on June 10. Grierson had previously suggested to Sturgis that the cavalry should feel out the Confederates to gauge their strength. Once that was done, they might try to draw them back for an engagement at Stubbs farm, where the ground was of their choosing. But Sturgis rejected the idea because he did not believe the enemy in front of them was large enough to pose a real threat to the expedition.

Instead, Sturgis ordered Grierson to stay in the vanguard and not interfere with the movement of the infantry and train. Grierson’s troopers set out from their bivouacs with Waring’s brigade leading the way southeast along the Ripley-Guntown Road followed by Winslow’s brigade. As for the infantry, it began moving along with the wagon train at 7:00 a.m.

Waring’s vanguard encountered Rebel pickets as they neared Brice’s Crossroads. Driving them back, the Federal troopers clattered across a narrow bridge over the swollen Tishomingo Creek and arrived at Brice’s Crossroads at mid-morning.

Waring dispatched troops to scout south towards Guntown and in both directions on the Baldwyn-Pontotoc road. When the detachment reached Baldwyn, it ran headlong into troopers from the Confederate 12th Kentucky Cavalry leading the way for Lyon’s Brigade. In the meantime, Waring’s brigade advanced a half-mile up the Baldwyn road and deployed at the edge of a wooded tract. Part of his force faced east, and another part faced south. It was just in time, as a few companies from Lyon’s Brigade, some mounted and others dismounted, soon probed their lines.

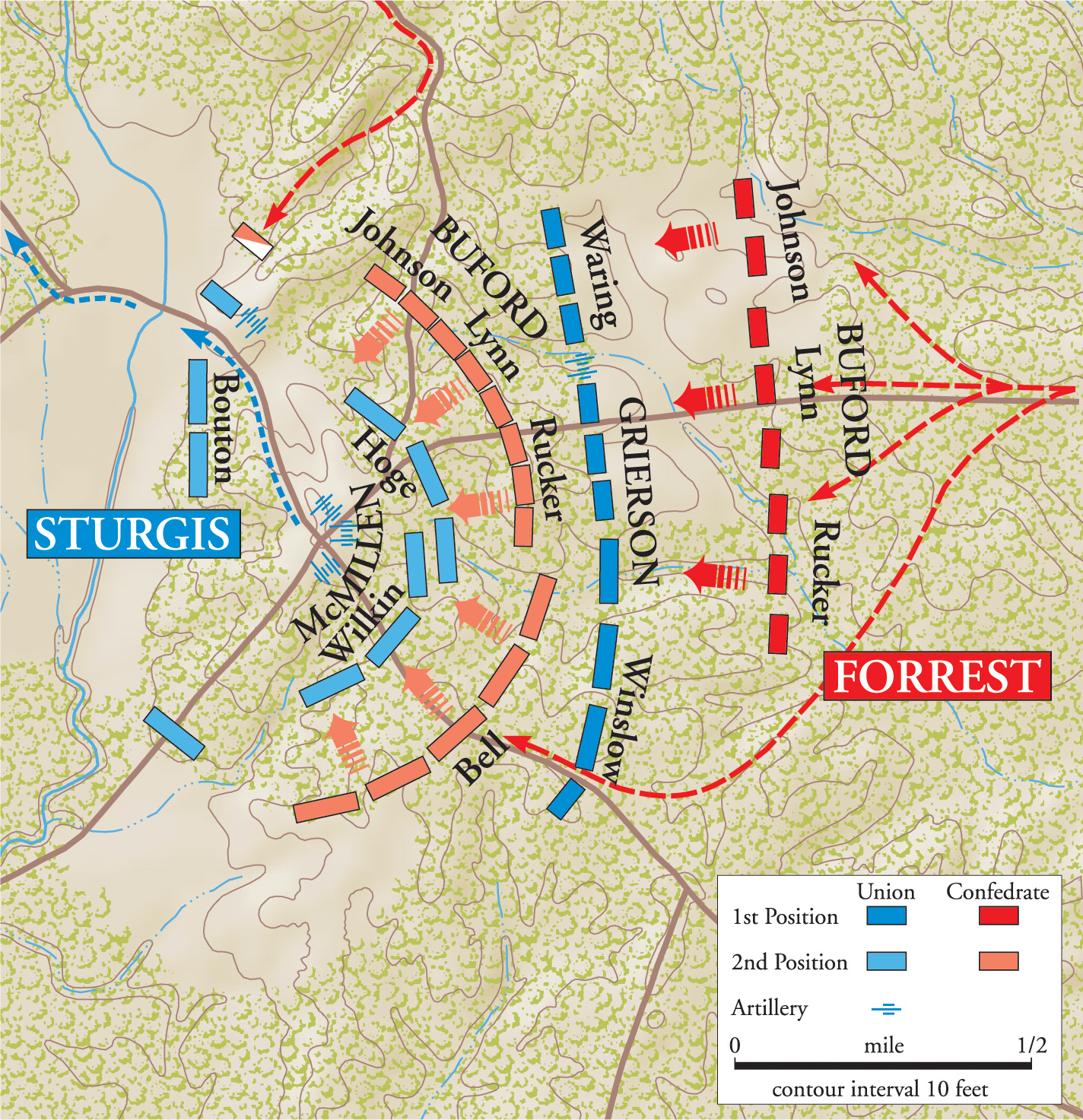

When word of the skirmishing reached Forrest, he sent a courier to Buford to order him to advance with the artillery and Bell’s Brigade. Next, he sent Lyon’s Brigade to attack the Federal line. Rucker’s brigade of Tennesseans and Mississippians and Johnson’s Alabamians soon arrived, and Forrest sent both forces into action. The Confederates attacked with their usual ferocity.

Waring’s dismounted troopers blazed away at Lyon’s men moving through the thick undergrowth. “The muzzle of carbine or musket was placed against the body of the assailants or the assailed, and discharged,” said Lieutenant Thomas Cogley of the 7th Indiana Cavalry. In many instances, the men did not have sufficient time to re-load their carbines, so they fought the Confederates with clubbed muskets and their fists.

Rucker’s Brigade soon entered the fray on Lyon’s right, moving through a knee-high cornfield. A vicious fire erupted from the Yankee troopers positioned behind a rail fence strengthened with logs. “It looked like death to go to the fence, but many of the men reached it,” said John Milton Hubbard of the 7th Tennessee Cavalry.

Some of the Tennesseans sought cover in a gully, but their lieutenant colonel ordered them forward. “Sheets of flame were along both lines while dense clouds of smoke rose above the heavily wooded field,” Hubbard said. The Federal troopers continued to cling to their position.

Johnson’s Alabamians struck Waring’s left flank hard. Waring had to remove troopers from his right flank, where Winslow’s Brigade had taken up position, and shift them to his battered left flank. This left a weak spot that Rucker and Lyons exploited by driving back the 7th Indiana Cavalry and 2nd New Jersey Cavalry. The entire Federal line fell back towards the crossroads. The Federal horse artillery continued to fire on the Confederates, which temporarily stabilized the battered Federal cavalry’s line.

Grierson informed Sturgis by messenger of the developing situation at the crossroads. He met Sturgis on the Ripley-Guntown road at a muddy patch of low ground known as Hatchie Bottom. The Federal infantry column had arrived, and Hoge’s Brigade was in the vanguard. After a brief discussion, Sturgis rode south with an escort for Brice’s Crossroads. Before he departed, the Federal commander ordered McMillen to have some of his men make for the Hatchie Bottom, over which the infantry and wagon train had to cross to reach the battlefield.

Sturgis also instructed McMillen to hurry forward Hoge’s Brigade to the crossroads to reinforce Grierson’s cavalry. Sturgis arrived at the crossroads shortly after midday. Upon his arrival, Sturgis observed that Grierson’s cavalry was being pressed hard by Forrest’s troopers. “The situation was one of considerable confusion,” recalled Sturgis.

Grierson overheard Sturgis say to one of his staff officers that if the Federal cavalry could be moved out of the way he might be able to whip the enemy with his infantry. But Grierson was staunchly proud of the work of his troopers. He said afterwards that they had held their own and had repulsed “with great slaughter three distinct and separate charges.” Little did Grierson know, though, the three charges were feints. Forrest still did not have all of his men up, and he made the assaults to keep the more numerous Federal cavalry off balance. Sturgis, keen to get his infantry into action with an eye towards defeating Forrest, sent word to McMillen to “make all haste [and] lose no time in coming up.”

Just then, Buford reached the crossroads with Colonel Bell’s brigade. At the same time, Captain Morton arrived with two artillery batteries. Forrest ordered Morton to deploy his guns in a field next to the Baldwyn Road. Morton was soon shelling the Federal cavalry at the crossroads. At the same time, Forrest instructed Bell to deploy his brigade on the far left of the Confederate line. Bell, in turn, ordered Barteau to take his 2nd Tennessee Cavalry and move around the Federal right flank and attack Sturgis’ wagon train on the Ripley-Guntown Road.

With his coat draped over the pommel of his saddle and sleeves rolled up, Forrest rode along the Confederate battle line with his sword in hand to encourage his men. Buford commanded the Confederate right, Rucker led the center, and Forrest personally supervised the Confederate left. Hubbard remembered Forrest telling his men that when they heard Bell’s guns and the bugle sounds, then “every man must charge, and we will give them hell.”

A lull fell over the battlefield at 1:30 p.m. as Forrest reorganized his troops and the worn-out Federal infantry began to arrive. The Yankees had endured a brutal march along the Ripley-Guntown Road in the intense heat. “As I rode along the moving column from regiment to regiment and saw the numerous cases of sunstroke, and the scores and hundreds of men, many of them known to me as good and true soldiers, falling out by the way, utterly powerless to move forward, it was a sad, a fearful reflection, that this condition of so many, would ensure a certain defeat, and terrible disaster,” said Dr. L. Dyer, Sturgis’ surgeon-in-chief.

When McMillen arrived with Hoge’s lead regiments at the crossroads, he quickly encountered demoralized cavalry, wagons, and artillery in retreat. The men of the 113th Illinois of Hoge’s Second Brigade arrived first, and they went into action northeast of the Brice house with their left on the Baldwyn Road.

“The tongues of many hung out of their mouths, and they couldn’t bite a cartridge,” said Hoge. From left to right, Hoge’s brigade deployed as follows: the 113th Illinois, 120th Illinois, 108th Illinois, 95th Illinois, and the 81st Illinois. Battery B of the 2nd Illinois Artillery unlimbered at the crossroads; as the battle progressed, its commander advanced one of his guns 400 yards forward along the Baldwyn Road.

Wilkin’s First Brigade arrived next. McMillen split up the regiments and fed them into the Federal battle line where they were most needed. The 95th Ohio took up in a wooded tract to the left of the 113th Illinois. McMillen sent the 72nd Ohio and the 6th Indiana Artillery to a ridge overlooking the bridge at Tishomingo Creek. He ordered 114th Illinois to move down the Ripley-Guntown Road and make contact with the right of the 81st Illinois, but owing to a lack of men they were unable to carry out the order. The 93rd Illinois also advanced along the same road and formed up just south of it. McMillen held the 9th Minnesota and 1st Illinois Light Artillery in reserve near the crossroads. The two infantry brigades relieved Waring’s and Winslow’s exhausted troopers, who had used up nearly all of the ammunition of their rapid-firing carbines.

Leaving behind one man to hold eight horses instead of the normal four, Bell moved forward with his brigade through the thick undergrowth, which cloaked much of their advance toward the Federal right, held by the 93rd Indiana and 114th Illinois. At first the Yankee soldiers were confused as to who the troops in their immediate front were, for they could see blue-colored uniforms as well as butternut clothing. To stay on the safe side, they opened fire. The dismounted 16th Tennessee Cavalry returned their fire. The flash and crash of musketry filled the air as the fighting see-sawed back and forth.

South of the Ripley-Guntown Road, the 93rd Indiana was equally confused as to the identity of advancing troops in the thick undergrowth. At first, they thought they might be Federal cavalrymen, as they could see blue and even a Union flag. They soon learned otherwise when a well-aimed volley from the dismounted troopers of the 19th Tennessee tore into their ranks. The Hoosiers immediately returned fire.

Both sides hammered away at each other. At one point, the 19th Tennessee Cavalry was on the verge of breaking, but the 8th Mississippi of Rucker’s Brigade went in to action on their left. The Mississippians, who were reinforced by a squadron of the 12th Kentucky Cavalry that was part of Forrest’s escort, hit the Yankees hard. “We soon drove the enemy out of the black-jack thickets in our front and soon had them on the run,” said Tyler.

When the soldiers of the 93rd Indiana began falling back, the soldiers of the 114th Illinois began to take fire on their exposed right flank. Soon they were taking fire on the left flank, as well. This occurred when Rucker hurled the 7th Tennessee and 18th Mississippi against the 81st and 95th Illinois.

The Illinois troops moved forward into the ensuing foray with bayonets fixed. “Kneel on the ground, men, draw your six-shooters, and don’t run!” Rucker yelled at his dismounted troops. Brutal fighting engulfed the troops before the men of the 81st Illinois fell back 300 yards to the crossroads. The 95th Illinois fared little better. As casualties began to mount and the men ran low on cartridges, they also fell back to the crossroads.

While the Union right was beginning to crumble, McMillen ordered the 9th Minnesota—being held in reserve near the crossroads—into action. The Minnesotans were to relieve the 93rd Indiana, “which had been contending against superior numbers until nearly annihilated,” according to Lt. Col. Josiah Marsh, the acting commander of the 9th Minnesota.

Pushing through the dense undergrowth, the men of the 9th Minnesota found themselves in a slugfest with the dismounted troopers of the 19th Tennessee, 8th Mississippi, and Tyler’s squadron of the 12th Kentucky.

“The enemy fought desperately for some time, but finally gave way and was thrown into disorder and confusion by the destructive fire of my brave boys,” said Marsh. The Minnesotans then launched a bayonet charge, driving the Confederates back about a quarter of a mile. Marsh believed he might have turned the Southerners’ left flank, but the canister from the Federal guns was flying through the regiment’s left flank. For that reason, the Minnesotans fell back to their former position, despite reluctance on the part of some of the soldiers in the regiment. Their attack did succeed in allowing the 93rd Indiana to resume its former position.

Bell rallied his men. He did so with the assistance of Forrest and his escort, who led them back into action. Forrest then rode down his line of battle, encouraging his troops to press the Yankees. Lyon’s Kentuckians advanced along the Baldwyn road toward the Brice’s house and Bethany Church. At the same time, Johnson’s Alabamians moved into position to turn the Federal left flank.

Running low on cartridges, the 113th Illinois were hard-pressed to stop the Confederates, as were the 95th Ohio. With these regiments giving way, the 120th and 108th Illinois soon found themselves falling back to the crossroads, as were most of the Federal troops. The situation only worsened as the hot, bloody afternoon drug on.

By that time, Colonel C.R. Barteau had finally gotten behind the Federal left flank with part of the 2nd Tennessee. To hide his small numbers, he spread his troopers out in a long skirmish line, taking full advantage of the cover afforded by the undergrowth and trees. In an effort to fool the Yankees into thinking his numbers were greater than they were, he had his bugler gallop along the line sounding the charge at different spots. Protecting the far Federal left was the 72nd Ohio, which began to blaze away at Barteau’s men.

It was growing late in the afternoon, and the arrival of Confederate reinforcements had enabled Forrest to push the Federals almost all the way back to Brice’s Crossroads. Forrest continued to ride along his line, encouraging his men. He promised them that one final push would sweep the Yankees from the field. To break the wavering Federal line, Forrest ordered Morton to advance four of his guns as close as possible to the enemy center for the final assault.

Loaded with double-shot canister, Morton’s guns blasted the Yankees as Forrest’s men swept forward. “The main line began to give way at various points,” said Sturgis. “Orders soon gave way to confusion and confusion to panic.” The situation only got worse as the Confederates proved unstoppable.

“The troops from all directions came crowding in like an avalanche from the battlefield, and I lost all possible control over them,” said Sturgis. Company E of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery under Captain John Fitch had been ordered by McMillen to hold the cross-roads at all hazards. They kept their remaining two guns firing for as long as possible and then limbered up and barely escaped capture.

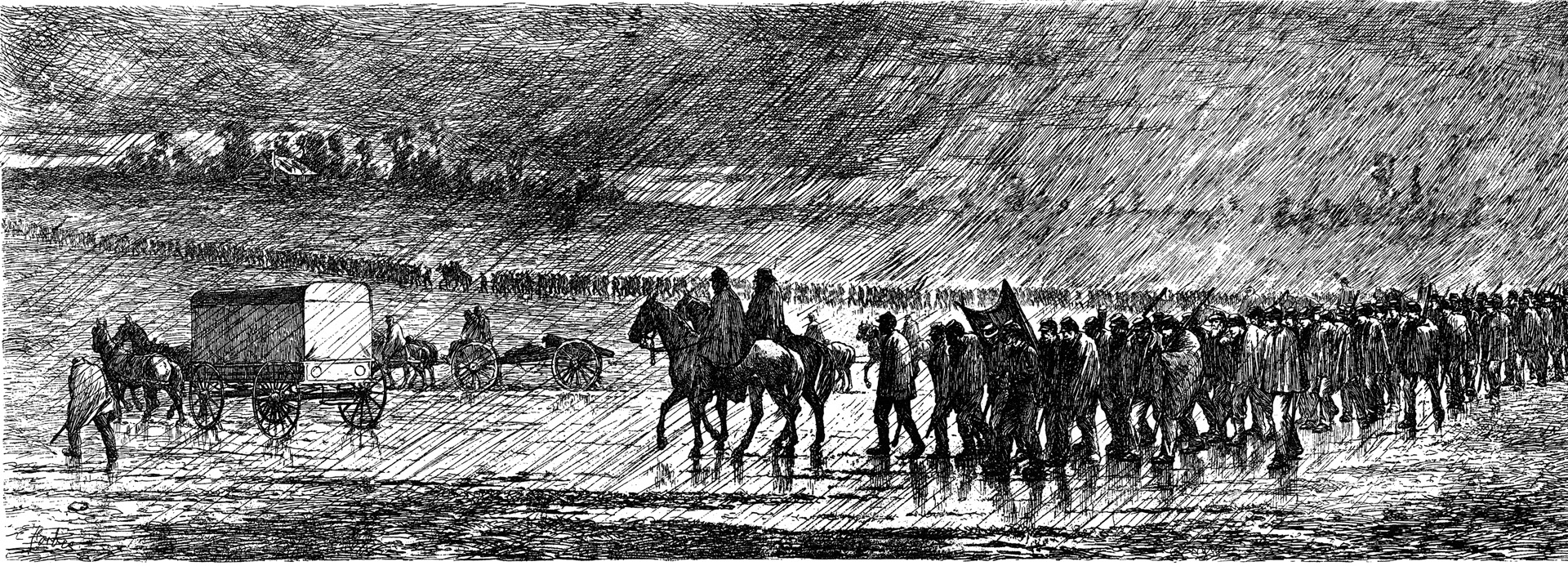

By this time, the wagon train had arrived, and some of the wagons were parked in a muddy field on the east side of Tishomingo Creek. As the Federal line turned into a stampede, the teamsters tried to get their wagons back across the bridge. They were not alone, as throngs of Yankees tried to escape Forrest’s juggernaut. All of this created a bottleneck, causing some to try and wade across the creek.

Forrest and his jubilant commanders soon met at the crossroads, but there was still work to be done yet. Morton had also arrived at the crossroads with his guns, and they were soon pounding away at the Federals and wagons, causing mayhem. Forrest had put the scare into the Yankees, and he meant to keep it there.

Moving at the double-quick to the sound of the battle, Bouton’s Third Brigade encountered worn and battered troops stumbling back up the Ripley-Guntown road. Two of the lead companies of the 55th U.S.C.T. pushed their way through the throngs of Yankees to get across the bridge and take up position with the 72nd Ohio and 4th Iowa Cavalry.

These units were Sturgis’ last line of defense, attempting to hold back the Confederates long enough for their comrades and wagons to get across the bridge. Seven more companies of the 55th U.S.C.T. deployed on the west side of the creek in support.

Heavily outnumbered, these troops were forced back across the bridge or plunged into the creek. The two black companies joined the rest of their regiment. They, along with the 72nd Ohio, attempted to stall the Confederate advance but were soon forced back. Many of the teamsters cut their mules loose, climbed onto to their backs, and rode off, leaving their wagons in the road.

About a mile north of the creek, Bouton organized another line to the stall the pursuing Confederates. The rearguard consisted of the 59th U.S.C.T., two guns of Battery F, 2nd Light Artillery, and the retreating 55th U.S.C.T., which had rejoined their brigade.

McMillen soon arrived. “[I will] fight the enemy as long as I have a man left,” Bouton told him. “If you can hold this position until I can go to the rear and form on the next ridge, you can save the entire command,” replied McMillen.

Bouton’s brigade bought McMillen precious time. They poured a heavy fire into the advancing Confederates and halted them. But the Confederates soon regrouped and outflanked the black troops, unleashing a deadly fire into them. Bouton’s men fell back but continued fighting as Forrest’s men repeatedly tried to outflank them, as well.

Further along the Ripley-Guntown Road at White House Ridge, the Federals formed yet another line at which to slow the Confederates. The 59th U.S.C.T., falling back, took up position to the right of 9th Minnesota. On the Minnesotans’ left was the 114th Illinois, while the 55th U.S.C.T., when it arrived, formed on the left rear of the line.

Morton’s four guns soon arrived to blast away at the Federals. Not far behind them was Forrest with Lyon’s brigade. Forrest led a charge across an open field, while the guns were advanced to within 150 yards of the Yankee line. The Confederate gunners let loose on the hapless Yankees with double-shotted canister.

Fierce fighting raged as the 59th U.S.C.T. fought desperately with bayonets and clubbed rifles. In the gloaming, the Confederates once again shattered the Federal line. Soon the Yankees were in full retreat to Hatchie Bottom. Fortunately for the Federals, Forrest decided to give his men a brief rest and allow them to eat. But he soon sent small detachments to harass the retreating enemy.

At Hatchie Bottom, the Federals were desperately trying to get their wagons, artillery, and ambulances through the muddy quagmire, but to little avail. Many of the guns were spiked and some dismounted and heaved into the sinkhole. The teams were unhitched from the stuck vehicles and left behind.

The Union army had to abandon some of their wounded to the enemy, too. “There in the wilderness, in the darkness and gloom of midnight, our wounded companions were taken out, and gently laid upon the bosom of mother earth—the precious trust left to the tender mercies of the advancing foe,” wrote Dyer.

Bouton arrived at the chaotic scene at 11:00 p.m. and did not like what he saw. “Give me the ammunition that the white troops were throwing away in the mud, and I will hold the enemy in check until we can get those ambulances, wagons, and artillery all over the bottom and save them,” he told Sturgis. But the Federal commander would have none of it. “If Forrest would let me alone, I will let him alone,” said Sturgis. “You have done all you could and more than we expected of you, and now all you can do is to save yourselves.”

Forrest had no intention of leaving Sturgis alone. For the next 30 hours, the Confederates pursued the retreating Yankees. They continued the chase for 60 miles before breaking off. The defeated Union army arrived in Memphis on June 13. Completely undone by Forrest and his crack troopers, Sturgis reported to his superiors that he had been defeated by 15,000 Confederates.

The Federals suffered 223 killed, 394 wounded, and 1,623 captured. They also lost 16 artillery pieces and 176 wagons. In contrast, Forrest lost 96 killed and 396 wounded.

Outnumbered two to one, Forrest’s stunning victory further boosted his fighting reputation not only among his peers in the Confederate army, but also among some of the commanders in the Union army. “[Forrest] has got some of our troops under cower,” Sherman said when he learned of Sturgis’ defeat.

Even though Sturgis had suffered a tactical defeat, he’d won a strategic victory by keeping Forrest from raiding Sherman’s supply line in middle Tennessee. But Sherman still feared for his supply line, and so he ordered more Federal troops from Memphis into Mississippi to pursue Forrest. They were to “follow Forrest to the death, if it cost 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury,” wrote Sherman. They would not succeed in killing Forrest, but they did succeed in keeping him from wrecking Sherman’s supply line.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments