By Eric Niderost

Standing on the quarterdeck of his flagship Bonhomme Richard, Commodore John Paul Jones took his telescope and trained it northwards, sweeping the instrument to the left and right to see what his lookouts were reporting at midafternoon on September 23, 1779. Jones was sailing at the time along the eastern edge of England just off the Yorkshire coast. On the port side of his vessel loomed a 150-foot-high chalky fist of land that jutted into the North Sea known as Flamborough Head. The sky was hazy, making the towering cliffs almost ethereal when viewed from a distance.

But Jones was more interested in the enemy ships he saw looming on the northern horizon. The lookouts cried out when they spotted enemy sail, and as more ships appeared in the distance, they repeated their warnings again and again. The commodore was delighted, since his own observations confirmed what they saw. It was the Baltic convoy of more than 40 British merchantmen loaded with ships’ stores, such as lumber, cordage, and canvas, for Britain’s Royal Navy. Centuries of shipbuilding had drastically reduced Britain’s forests, and by the 18th century the island nation depended heavily on the resource-rich nations of Scandinavia to maintain its vaunted navy.

Four years into the American Revolutionary War, the fledgling United States was struggling to win its independence from Great Britain, and while France was now an open ally, the outcome was still very much in doubt. Jones was an officer in the infant country’s Continental Navy and knew that if he could capture the merchant fleet before him, Britain’s shipbuilding efforts might well be severely compromised.

Jones’ squadron comprised his 40-gun French-built Bonhomme Richard, the 26-gun corvette Pallas, the 12-gun brig Vengeance, the 18-gun cutter Cerf, and the 36-gun American-built frigate Alliance. With luck, the Americans could easily capture the heavily laden British merchant vessels. Their captains were keenly conscious of the danger approaching them, and already were trying to scatter like a flock of terrified sheep. Normally, these frantic attempts at escape would be an exercise in futility, but the convoy had a Royal Navy escort to protect it.

The HMS Serapis was a new and powerful frigate. The Serapis was a 44-gun frigate, but it actually possessed 50 cannon. It was accompanied by the 22-gun sloop-of-war HMS Countess of Scarborough. The British frigate would be a hard to defeat, but Jones was confident he would emerge triumphant. The odds, and even the statistics, seemed to be in his favor. His squadron’s combined firepower could hurl more than 1,000 pounds of iron in a single broadside. If Jones could maneuver his ships to get on both sides of Serapis, the British frigate would be pummeled into submission.

Eager to get into action, the commodore noted the light breezes and ordered royals be set on his ship’s masts, the topmost sails on a square-rigged vessel. When even those additions seemed inadequate, Jones further ordered studding sails set port and starboard. These were extra sails that stuck out from the regular ones, making a ship look as if it had sprouted large white wings. They were used to catch even the slightest bit of wind.

Even with the additional help, progress was painfully slow, perhaps only about a mile an hour. Bonhomme Richard originally was a merchant ship built for transporting cargo, not for speed. She was as slow as a snail even under favorable conditions. She was also running against the tide, and the continuing light winds certainly did not help her.

Jones stood on his quarterdeck, occasionally pacing in the confined space, pausing only to lift his telescope to make a sighting of the enemy. A handsome man, with his hazel eyes, dark brown hair pulled back and tied with a ribbon, prominent nose, and thin lips, Jones was the personification of confidence. Standing about five-feet-five in height, Jones may have been short, but he was a giant presence.

It took more than three hours for the Bonhomme Richard to close with the Serapis, which was ample time for Jones to ponder the upcoming engagement and recall the series of events that brought him to this day and this hour. No officer of the Continental Navy had defeated and captured a Royal Navy warship of any real size and strength. In a sense, Jones had been striving for this opportunity his entire adult life; if he won, he would gain the heroic honor and immortal fame that he so dearly coveted.

John Paul (he tacked on Jones later in life) was born in 1747 on the estate of Arbigland in southwestern Scotland. He was the son of a gardener whose work closely resembled that of a modern-day landscape architect. He went to sea at the young age of 13 and became an apprentice sailor on a merchant ship. In 1768, at the age of 21, he became master of his own ship.

In 1773, a series of events unfolded that would profoundly change Jones’ life and career. He was master of the merchant ship Betsy, carrying a load of butter and wine from London to the West Indies. The butter went bad, and his ship was found to need urgent repairs. The maintenance work was something that he could not afford at the time.

But it was at Tobago that the real trouble started. One of the seamen, a “prodigious brute of thrice my strength,” according to John Paul, became a ringleader in a mutiny. The brute demanded money so the crew could go ashore and have fun with drink and women, but John Paul refused. What money he had left was earmarked to get another cargo to transport back to London.

Angry and defiant, the mutineer brute grabbed a bludgeon and advanced on John Paul, apparently intending to brain the Scotsman. Cornered near his cabin, John Paul took his sword and ran his assailant through. It was an act of self-defense, but the brute was a Tobago local, and he feared he might be charged with murder. It would be a trial by jury, and the theoretically impartial jurors might well be friends of the deceased.

Discretion being the better part of valor, John Paul fled. He arrived in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in late 1774 with just enough money to survive independently for a few months. Along the way he tacked on a new surname to cover his tracks. He was now John Paul Jones. Although he did not know it, his timing was impeccable, because the Britain’s American colonies would soon attempt to win independence from the mother country.

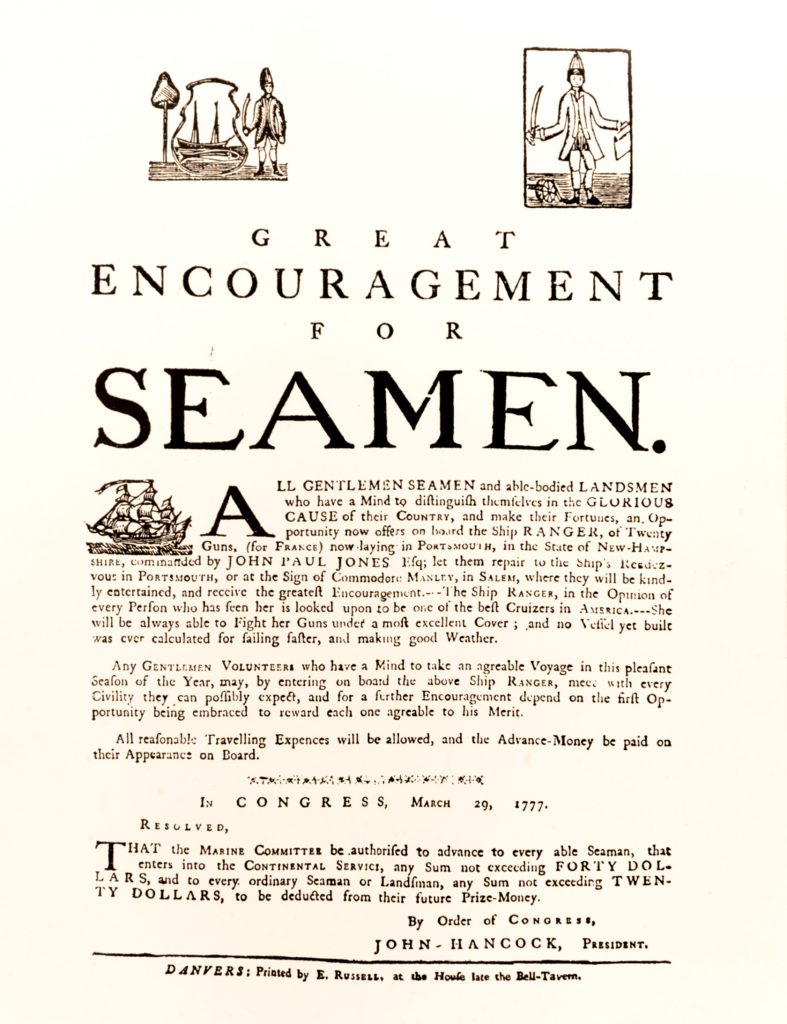

In autumn 1775 the Continental Congress, recognizing the need for sea power of some kind, formed a seven-man Naval Committee to lay the groundwork for a fledgling navy. The committee comprised reasonable men, and certainly not fools. The British Royal Navy was the most powerful sea force in existence. Of its 270 ships, 131 were ships-of-the-line carrying more than 50 guns.

Nevertheless, a rudimentary Continental Navy soon took shape. Some ships were built, but various American vessels, mostly merchantmen, were pressed into service. There was an almost desperate need for ship’s officers, and Jones lost no time in coming forward to serve. He was commissioned in December 1775 as a first lieutenant aboard the Alfred, yet another slab-sided, aging merchant vessel converted into a man-of-war.

The next couple of years Jones, served on several ships and eventually became master of his own vessel. He gained a reputation as a brave and resourceful sailor, but his crews did not like him. While no martinet, he was a strict disciplinarian who drove his men hard. Jones was constantly seeking to improve ship performance, and he made sure that the men did their parts in achieving that goal.

His most famous command before Bonhomme Richard was the sloop Ranger, square rigged on all three masts and carrying eighteen 9-pounders. Ranger was a new ship, built in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Jones could see she was fine-lined and gave every promise of speed.

Those who knew Jones found him to be self-absorbed, desirous of fame, eager for advancement, sensitive regarding his honor, quick to anger, and ready to complain to higher authority about insults real or imagined. He was also a good seaman, genuinely fond of his adopted country, and prescient in his insistence that America must eventually build a powerful navy.

But all this meant little to the Ranger’s crew, except perhaps his volcanic temper. They were New Englanders, mostly from New Hampshire and Massachusetts, who possessed a sense of independence and self-worth that typified the Patriot cause. Many of them were fishermen in civilian life, where a ship’s captain was first among equals, not the authoritarian demigod who all must obey without question.

Jones planned to do as much damage to British shipping as he could. He intended to sink ocean-going merchant craft, coastal traders, and fishing boats. He also planned to stage raids on at least one, and perhaps two, British ports. He planned to lie in wait off the ports and then strike quickly using the element of surprise to its fullest advantage. Not that he was avoiding British warships; he welcomed a fight, provided he was not outnumbered or faced with an opponent that outgunned the Ranger. “I intend to go in harm’s way,” he vowed.

Another part of his plan involved a measure of compassion for the many American sailors languishing in fetid British prisons. He planned to take an important British hostage in the hope of exchanging his high-born prisoner for the American captives. But first, he would raid Whitehaven, a port in northwestern England. He knew the waters well, for he had shipped out of Whitehaven as a young apprentice seaman many years earlier.

The Whitehaven raid was simple in concept but dangerous in execution. Jones intended to sneak into the two forts that guarded the port and spike their cannon. Once that was accomplished, he would put to the torch all the ships that were sheltering in the harbor. At times there might be several hundred merchantmen and fishing boats in the harbor, so it was well worth his while to stage such a raid.

But first Jones had to persuade both his reluctant crewmen and their uncooperative officers to support the raid. The commodore did manage to get about 30 members of the crew to volunteer, but only after long-winded and impassioned arguments. All of this persuasion took time, and dawn was breaking when Jones and his raiders finally landed at Whitehaven.

The first phase of the operation, on April 22, 1778, was successful. The guards in the first fort were overpowered under cover of darkness without a struggle and the cannon quickly spiked. Jones returned safely from the fort but was astonished and dismayed when he learned that the party assigned to set the ships ablaze had not set even one vessel afire. Eventually one large collier (a ship carrying coal) caught fire. But the noise roused the citizens of Whitehaven; they rushed to the docks, where they found the collier engulfed in flames. Jones drew his pistol and sternly ordered the crowd to disperse; fortunately, it did exactly what he ordered. The second phase of the operation involved the kidnapping of Lord Selkirk, but the kidnapping was unsuccessful given that Selkirk was in London at the time. Nevertheless, a raiding party plundered the manor house of all of its silver two days later.

Up to that point, the Ranger’s voyage had been bloodless, but this was not to last. Ranger encountered the British sloop-of-war Drake and captured it after a short but bloody fight. Jones returned to Brest with a growing reputation. But he did not receive a new command immediately. For the next 10 months he languished in Paris, though he was lucky to have Benjamin Franklin, the American emissary to the French court, as his friend.

Jones’ desires were subject to the exigencies of politics and war. He was promised a frigate, and one was being built for the Americans in Holland, but the Dutch were neutral at the time and had second thoughts about angering the British. Casting about for a solution, Franklin and the American commissioners decided to sell her to the French.

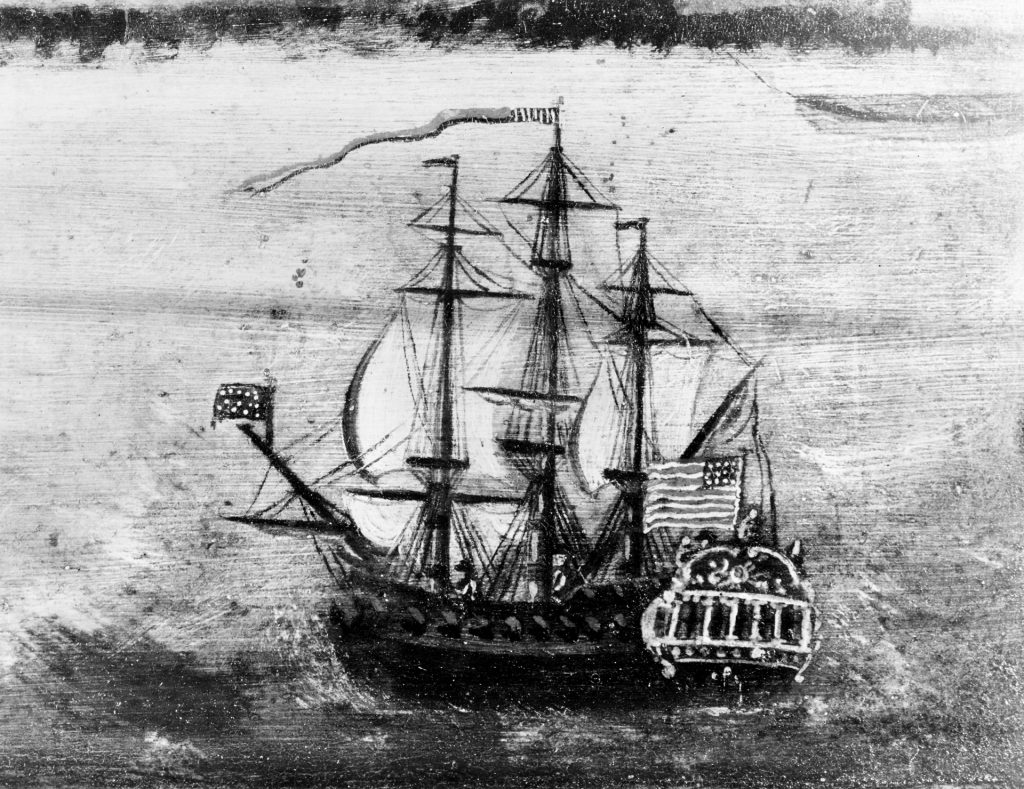

After many long months of waiting and disappointment, a ray of hope shined for Jones. The 900-ton French Indiaman Duc de Duras was for sale. The French government bought the vessel for Jones, and King Louis XVI personally provided the funds to have her outfitted. Built for trade and not war, the merchantman was sturdy and designed for the long and often-perilous voyage to the east. Pleased to get a ship after months of cooling his heels in frustration, Jones renamed the vessel Bonhomme Richard, which translates to “Poor Richard,” in honor of his friend and mentor Franklin’s famous almanac.

The ship was armed with six 9-pounders on the upper deck and twenty-eight 12-pounders on its main gun deck. But Jones knew he needed more firepower. The designation “pounder” came from the weight of the solid shot used; for example, a 12-pounder fired cannonballs weighing 12 pounds each. The Scotsman placed his hopes on the six 18-pounders, three on each side, that he was able to acquire for Bonhomme Richard. But they were old and unreliable, in essence rejects that no one else wanted. But beggars cannot be choosers, and therefore Jones held his tongue and kept his temper.

The ship had to be altered to accommodate the 18-pounders. Additional ports had to be cut in the ship’s hull, and they were so near the waterline they could not be opened unless the sea was flat calm. There were 380 men aboard Bonhomme Richard, each individual reviewed by Jones himself. The sailors were a heterogeneous bunch, hailing not only from Europe and America but also the fabled lands of the Orient.

Jones succeeded in weeding out the worst of the lot, but those that remained were still far from the lighthearted “jolly tar” of 18th-century lore. “They were generally so mean that the only expedient I could find that allowed me command was to divide them into two parties and let one group of rogues guard the other,” wrote Jones. The crew was a volatile stew of humanity that included not only English, French, Irish, and Scottish, but also Norwegian, Swiss, Italian, Bengali, and East Indian seamen.

But Jones had some luck, too. He had managed to negotiate a prisoner exchange, and as a result, 100 American seamen obtained their freedom. Of these, 62 signed to serve aboard Bonhomme Richard, giving Jones a dependable American core to his command. These men were not only Americans, but also were heavily motivated to fight. The weeks of brutality in British custody gave them an added incentive to sail with Jones.

Jones was also fortunate in his officers. For example, Richard Dale had served with Jones before and had risen through the ranks from ordinary seaman. But there was one exception: Captain Pierre Landais. A Frenchman, he had obtained an American commission and was further rewarded with the command of the frigate Alliance. He technically was part of Jones’ squadron, but practically he did what he pleased. Because of this, he became a thorn in the commodore’s side from the outset.

The 1779 cruise began in good weather, and prizes were taken. Jones captured the merchantman Union, which was bound for Quebec with its hold crammed with stores destined for the British army, on September 1. Over the course of the voyage, Landais occasionally would break off and sail away without informing Jones. Unfortunately, he rejoined the squadron just before the Flamborough Head fight, where he was to do more harm than good.

During the voyage Jones moved quickly to crush a potential mutiny by some of his English-born sailors before it could unfold. These sailors had been released from French jails, and they were scoundrels who had a history of surly disobedience and mutiny. Jones, who usually was humane by the standards of the day, had the ringleader sentenced to 250 lashes. He got the point across, and the crew became a surprisingly cohesive and effective fighting force.

The sun was slowly setting on the afternoon of September 23 off Flamborough Head when Jones ordered the drummers to beat to quarters. It was 5:00 pm, and the agonizingly slow journey to reach Serapis had already taken two hours, with at least another hour or more to go.

But the drummers’ throbbing tattoo rumbled through the ship, a signal to man battle stations, and galvanized every soul aboard Bonhomme Richard. Some sailors scrambled aloft, bracing the yards with chains so they would not fall on the deck below if hit by enemy fire. Gun crews reported to their assigned cannon, while marines and picked sailors started to limb the shrouds to reach the fighting tops. Below decks, 21-year-old surgeon Laurence Brooke was preparing the cockpit for the wounded. He readied the tools of his profession, which included a variety of saws and knives for amputations, to treat the wounded that would be brought down from the deck. We do not know if he had a brazier of coals to heat his instruments, a technique used to lessen the shock of cold steel.

The fighting tops were going to play a crucial role in the upcoming battle. The Bonhomme Richard had three principal masts, and masts of the period usually were not a single pole, but several segments bound together. A fighting top was a platform that was located near to where the lower portion of the mast joined the upper portion. The fighting top could be quite high—as much as 50 feet above the deck—and certainly not for anyone even mildly acrophobic.

Midshipman Nathaniel Fanning was the captain of the main top, and he left a stirring account of the battle in later years. As the Bonhomme Richard got closer to Serapis, Jones called for an officer’s conference to explain his battle strategy and outline their roles in the upcoming drama. He intended for his smaller cannon, like the 9-pounders, to cut up the enemy ship’s rigging and puncture its canvas sails. The object was to damage the Serapis’ ability to maneuver.

Jones’s heavy ordinance, such as his 18-pounders, would do the heavy and unglamorous work of shattering the British ship’s hull while at the same time damaging its guns and killing and wounding its gun crews. Jones tried to be a sensitive ladies’ man ashore and even tried his hand at poetry, but on the quarterdeck he was a hard-headed realist.

Serapis was a new frigate, only a few months from the builder’s yard, and could sail circles around the old and cumbersome French Indiaman. The British ship also outgunned Bonhomme Richard. But if Jones could cripple the Serapis, he might be able to capture it.

Jones also spoke directly to Fanning and the other two midshipmen commanding the fore and mizzen tops. Twenty-four-year-old Fanning was the eldest of the trio, for the others were not yet 17 years-old. The commodore told them their first duty was to neutralize the British fighting tops. After that, they were to train their weapons on Serapis’ exposed top decks. It was a favorite British tactic to rain down such a heavy fire from their own foretops that officers and men on the enemy vessel would be slaughtered. Jones proposed to turn the tables on the British by doing the exact same thing to Serapis.

Once they finished their conference with John Paul Jones, the three top captains joined their men, who were already in their high wooden eyries. Fanning had 15 marines and four sailors in his main-top command. They were armed with muskets, blunderbusses, swivel cannon, and coehorns (mortars). Biting the gunpowder-filled cartridges when loading muskets, coupled with the heat and tension of battle, often produced a raging thirst, so a cask of water was brought up to the main top. Jones also issued orders that the top men were to have a double ration of grog to steel them for the coming ordeal.

It was about 6:00 pm when the sun set. Its waning rays glowed reddish orange on the western horizon as it dipped behind the cliffs of Flamborough Head. At the moment Jones had three ships with him: the Alliance was ahead of the Bonhomme Richard, the Pallas astern, and the Vengeance trailing. Jones ordered signal flags to be hoisted: a blue flag, a blue pennant, and a blue and yellow flag. Although the signal flags called for the ships to form a line of battle, the command was almost always universally ignored. The Pallas decided to chase and capture Countess of Scarborough, the Vengeance just milled about, and Alliance took itself completely out of the brewing battle.

This left Jones to fight the Serapis with just the Bonhomme Richard. The odds of victory against a new British frigate seemed suddenly remote. When Bonhomme Richard and Serapis were within pistol-shot range of each other, which was about 25 yards, Captain Richard Pearson was not sure whether the other ship was an enemy vessel. In order to gain a slight advantage, Jones had issued orders for his crew to pretend that the Bonhomme Richard was a British vessel. It was a clever move on his part.

Pearson was puzzled. The Bonhomme Richard was flying British colors, and he could see in the gathering darkness Jones was wearing a white-and-blue uniform that looked like Royal Navy. “What ship is that?” hailed Pearson. “The Princess Royal,” replied Jones. The British captain followed up by asking where the ship was from, but Jones ignored he question.

Both ships had their gun ports open, with the stubby black ends of cannon poking through each hole. Their crews waited for the order to fire amid mounting tension that sent adrenaline coursing through their veins. “Answer immediately or I shall fire into you!” shouted Pearson.

Jones then ordered the British ensign taken down and replaced by the American flag at the same time he ordered his crew to fire a broadside. Gouts of flame lanced through clouds of grey-white smoke as the guns roared to malevolent life. Serapis responded in kind. The broadsides marked the beginning of a fierce clash that was destined to last for hours.

Cannonballs smashed through the wooden hulls, killing, wounding, and horribly maiming seamen on both vessels until the decks literally ran red with blood. Any person unfortunate enough to be in the direct path of such an iron projectile might be disemboweled or decapitated. As the cannonballs crashed through the hulls, they sprayed large wooden splinters through the air. These deadly fragments lacerated flesh, producing horrible, potentially fatal wounds.

The crew of the Bonhomme Richard initially held its own against that of the Serapis. During the course of the fight, two of the American ship’s aging and unreliable 18-pounders blew up of their own accord, wreaking horrible devastation on the gun room. The explosion blasted a hole in the ship’s starboard side right above the waterline and killed and dismembered the hapless gun crews. The survivors were scorched, blackened, and bloody. They lay scattered amidst the debris, writhing in agony.

Jones did not have to survey the carnage to understand what had happened. He immediately ordered that the gun room be abandoned; this meant all his 18-pounders were out of action, even the ones still apparently intact. But he could not take the chance on a further mishap. The explosion also helped him determine his next course of action.

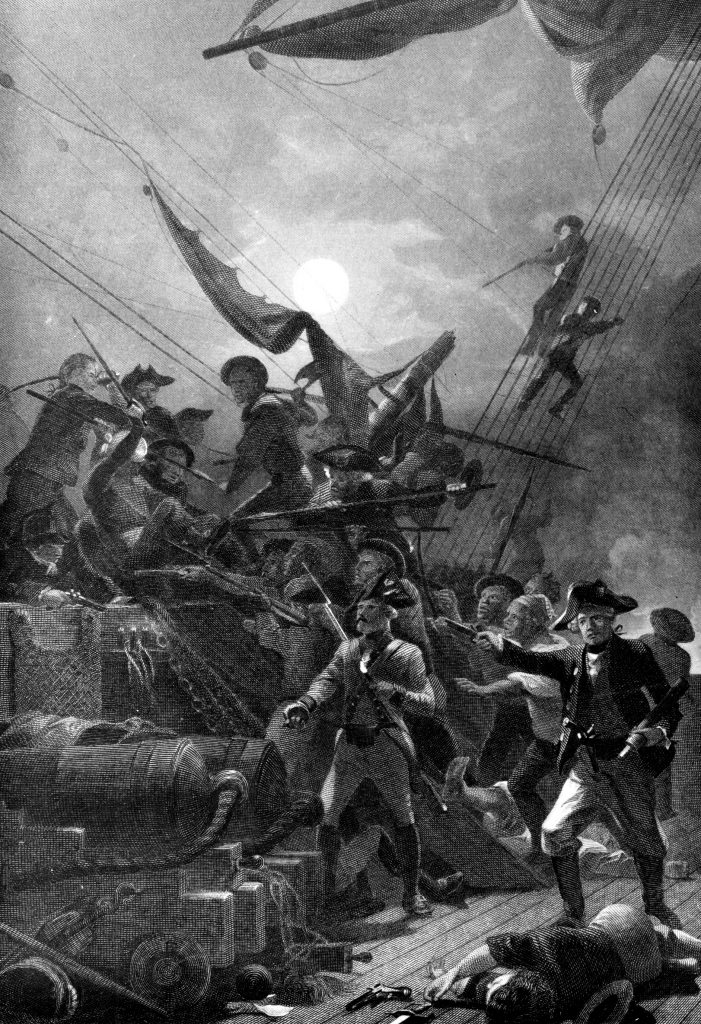

Jones could see that the Serapis was faster and far more maneuverable. All Pearson had to do was keep his distance while slowly and methodically blasting to pieces the Bonhomme Richard. The Scotsman knew his only chance of success was to get close enough to Serapis to grapple and board the British frigate.

The two opposing warships maneuvered for advantage in a deadly ballet of war that must have seemed an eternity to the participants. After a while, Jones had a lucky break. “The enemy’s bowsprit, however, came over Bonhomme Richard’s poop by the mizzen mast and I made both ships fast together in that situation,” he recounted. “[The] action of the wind on the enemy’s sails, forced her stern close to Bonhomme Richard’s bow, so that the ships lay square alongside each other, the yards being all entangled and the cannon of each ship touching the opponent’s side.”

The lower deck on the Serapis’ starboard side was so close to Bonhomme Richard that the lids on the gun ports could not be raised. Because of this, the British gun crews literally had to blow them open. Some aspects of the fight, which had degenerated into a bloody, no-holds-barred contest, bordered on the surreal. To use their rammers, gun crews literally had to thrust them into the enemy’s ports.

Pearson desperately wanted to free his ship from Bonhomme Richard’s embrace, but Jones made sure scores of grappling hooks prevented such an escape. It was here that the fighting tops and marines came into their own. They engaged in a deadly eagle’s-perch duel with their counterparts aboard the British fighting tops. Once they had successfully accomplished that task, they turned their attention to the upper decks of the British frigate.

The topmen poured heavy and accurate fire into Serapis, clearing its upper decks of any British sailor or marine who dared show his face. When British tars rushed forward with axes and attempted to chop the grappling lines, they were cut down before accomplishing their task. Pearson had to retreat from the quarterdeck and seek shelter at 8:30 pm.

By that time the moon had risen high enough that it cast its pale beams down on the warring vessels and bathed the surrounding sea in a silvery glow. As for the wind, it had died down. This transformed the surface of the sea into what mariners call a “flat calm.”

The Bonhomme Richard’s decks were a shambles, a wrecked labyrinth of splintered wood, overturned gun carriages, and the bloodied, eviscerated bodies of men. One by one Jones’s 12-pounder cannon were put out of action, until all he had left were three 9-pounders on the quarterdeck. Jones took command of one of his 9-pounders, aiming it at the mainmast of Serapis.

But the British ship’s 18-pounder battery blazed away with renewed vigor, tearing so many holes at or below the waterline of the Bonhomme Richard that the ship began to take on water. The pumps were manned, but within a short time the American ship’s hold was filled with five feet of water. What is more, both ships were soon ablaze.

Wooden warships were extremely vulnerable to fire. Burning cartridge wads from cannons, especially from those fired at point-black range, were one of the chief culprits. The kindling was everywhere, including tarred ropes from cut-up rigging, scraps of canvas from ripped sails, and splintered pieces of wood from shattered bulkheads. The fires started below, but tendrils of flame danced up the dangling ropes and shredded canvas, leaving a fiery trail in their wake as they engulfed the spars and sails.

Fanning and his main topmen quickly realized they were in serious trouble because the spars, sails, and even portions of the fight top itself were ablaze, a conflagration that threatened to engulf them in one all-consuming inferno. Fanning used contents of the water cask he had brought up to quench his men’s thirst, to douse the flames. It was not enough, so Fanning and his men removed their coats and used them to beat out the flames.

The story was the same in both ships. Both Serapis and Bonhomme Richard were aflame; the threat of death by fire or smoke was so great to both sides that fighting actually was suspended for a time. But once the fires were extinguished, or at least under control, the slaughter resumed.

In all the confusion and carnage, two members of Jones’ crew sought to surrender the vessel. “Quarters!” they shouted repeatedly, using the naval term for surrender. Pearson, who heard their pleas through the murderous din of battle, went to his quarterdeck rail. “Have you struck?” he asked. “Do you call for quarters?” To haul down his colors in abject surrender was unthinkable to the doughty Scotsman.

Jones’ reply to Pearson is the stuff of legend, and helped Jones achieve immortality. Jones stood up straight and proud and gave a defiant answer. “I have not yet begun to fight!” he shouted. This is actually a shortened version of what Jones actually said; the idealized version was first set forth in an 1825 biography about Jones based on First Lieutenant Dale’s account of the event. The Edinburgh Advertiser published an account of the event shortly after the battle that in all likelihood was closer to what Jones actually said: “I may sink, but I’ll be damned if I strike!”

Warning shouts of alarm could be heard above the crackle of musketry and boom of cannon; a party of British sailors and marines armed with cutlasses and pistols were attempting to board Bonhomme Richard. Spilling over the bulwark, they ran down the American ship’s gangway to the quarterdeck ladder. Jones grabbed a boarding pike and led some seamen to meet the invaders, a hand-to-hand struggle that was vicious and bloody.

Thrust, parry, and stab, the two opposing groups fought with a special fierceness, since some of the American seamen had been abused as British prisoners, and they were eager to exact revenge. The British fought well, but the Americans overpowered them. The British then retreated back to the Serapis.

The danger had been averted, but the Bonhomme Richard seemed to be in its death throes. The ship was filling with sea water, and the hull was so riddled with shot holes that it did not seem as if it could support the upper deck much longer. It seemed a real possibility at that point that the seamen on the upper deck might panic and retreat to the lower deck.

The other ships in Jones’s squadron were still curiously passive. To their credit, the crew of the Pallas captured the Countess of Scarborough after a brief, but sharp, fight. At that point, Landais of the Alliance decided to join the fray. He inexplicably ordered his crew to fire broadsides not just into Serapis, but also into Bonhomme Richard. Unfortunately for Jones and his crew, the Bonhomme Richard received the bulk of Alliance’s attentions. Jones was incredulous. He signaled to Landais to break off his attack. Only after firing one or two more broadsides did the Frenchman obey.

As if Jones did not have enough on his hands, 100 British seamen, prisoners who had been captured from earlier vessels, were now freed from the flooding holds. It was a humanitarian gesture, but one that put Bonhomme Richard in jeopardy. If they had had the presence of mind, they might have overwhelmed Jones and his remaining crew. Yet in all the confusion they meekly manned the pumps. Because of this, they posed no immediate threat.

Scottish top man William Hamilton helped Jones and the Bonhomme Richard win the battle. It was 10:15 pm when Hamilton gingerly moved along the footropes of the main yard, carrying a leather bucket of grenades and a slow match to ignite them. The two ships were so close Bonhomme Richard’s main yard extended over Serapis’ deck, making it a perfect platform to lob grenades.

A sharp-eyed Hamilton had noticed that a hatch aboard Serapis was half open, and that hatch led to the frigate’s lower gun deck. British powder monkeys—young lads who transported cartridges from the powder magazine to the gun stations—were outpacing Serapis’ exhausted gun crews. They were supplying cartridges faster than the gun crews could use them, and the surplus cartridges were piling up near the guns. Some of the cartridges had ripped open, spilling their contents. Having so much loose gunpowder on the lower gun deck was a recipe for disaster.

Hamilton began tossing grenades from his high perch about the decks, aiming for that hatch so carelessly left open. His missed the first two attempts, but then, fortune smiled. One of his grenades rolled down the hatchway into the frigate’s lower deck. The resulting explosion produced a huge yellow-orange fireball that roared to malevolent life, made worse by the narrow confines of the lower gun deck.

The explosion killed 20 British tars. Some had their limbs torn from their bodies by the force of the blast. Many others lay sprawled on the ground writhing in agony. Even some of the luckier survivors must have been in a state of shock. Moreover, some of them were completely naked, for their clothes had been blown off by the force of the blast. Only their shirt collars still hung around their necks.

Because of the blast, the odds were now stacked heavily against the Serapis. The horrific explosion had wreaked terrible destruction on her lower deck, and five guns were put out of action. The Serapis’ 150-foot mainmast, whittled by the constant strikes of Jones’s nine-pounder, was on the verge of collapse. What is more, the ship was on fire in a dozen places, and half of its crew was either dead or wounded.

Pearson believed he had done all required of him by the existing code of honor and that it was time to surrender. “Sir!” he called out to Jones, “I have struck! I ask for quarter!” “If you have struck,” Jones responded, “then haul down your ensign.” Pearson, summoning all the dignity he could muster, walked to the taffrail and took down the huge Royal Navy ensign with his own hands.

Jones had triumphed in an extremely hard-fought battle. The Bonhomme Richard also suffered greatly, losing about half its crew dead and wounded. But the physical damage to the ship was so great it was beyond repair. The timbers on the lower deck were “mangled beyond my powers of description,” recalled Jones. Soon the pumps were overwhelmed, and it was plain the battered old Indiaman would sink.

Jones had no choice but to order abandon ship after the wounded were transferred to Serapis. The gallant old merchantman slipped beneath the waves a day after the battle. Although his ship was gone, Jones’ legend was secure. He became a celebrity on the continent. His fame was greatest in Holland, France, and the fledgling United States.

After the war, his fortunes were mixed. He entered Russian service for a time, but always hoped to be reemployed by his true love, the United States. He died in Paris in 1792, wracked with a form of kidney disease, and for more than a century he was all but forgotten. His body was found in 1905. President Theodore Roosevelt then ordered a squadron of 11 warships to sail to Cherbourg, France, and transport the remains to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where the “Father of the U.S. Navy” Jones was interred with full honors in a crypt beneath the chapel floor.