By Kevin M. Hymel

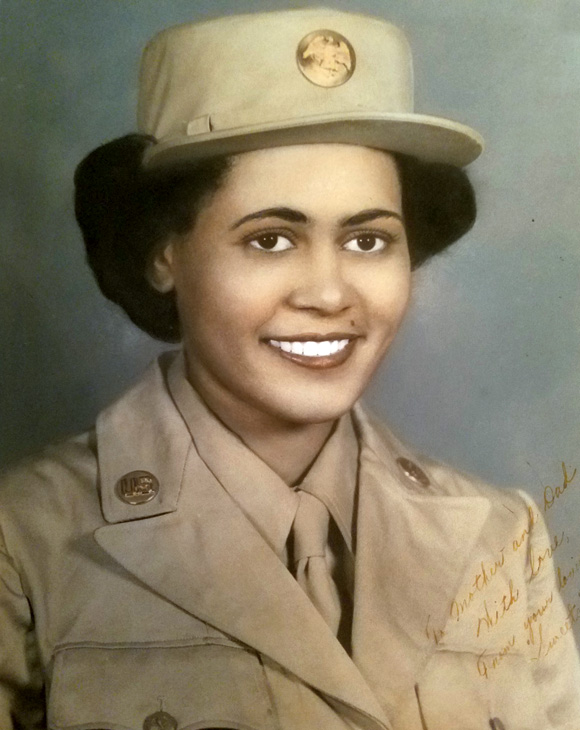

Although Private First Class (Pfc) Romay C. Johnson served in war-torn England and France during World War II, it was her tumultuous voyage across the Atlantic Ocean that she remembered most vividly.

“We didn’t know if we were going to make it,” explained Johnson.

Johnson and 737 other African American volunteers of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) had departed New York Harbor a few days earlier, on February 2, 1945, in the SS Il de France, a converted luxury liner, when a storm hit. The ship pitched and rocked in the heavy swells. Curious to see a storm at sea, Johnson left her sleeping area inside the ship and rushed outside. As waves crashed over the deck, she watched the ship’s bow crest a wave and rise out of the water, then crash down as the stern rose up and the propellers chopped at the air. “I would watch to see if I could see the bottom of the ocean,” she recalled.

She could not believe the view before her. “I never thought of the ocean as a monster,” she said. In the distance, she saw a ship so far away it looked like a helpless piece of paper on top of a wave one minute, and in a valley of water the next. Her worried friends inside called to her, “Johnnie where are you?” using her nickname. “We need you!”

Johnson wanted to remain on deck and watch the waves, but she eventually returned to her bunk area where she found distressed women screaming. They had to hold onto their bunks for balance and could not stand up or walk. Many succumbed to sea sickness. Yet Johnson, who as a child often succumbed to car sickness, felt immune. “Everyone got sick except me,” she said. “I was just too excited.” Despite the thrill, she never really got used to the waves. “They made your heart stop beating.”

If the storm didn’t unnerve her, a U-boat attack a few days later did. Although the ship sailed in a zig-zag pattern to make itself a poor target for German U-boats, one day it lurched to the side, throwing women in the upper bunks to the floor. Johnson could hear things rolling around in the ship. “We were told that a torpedo had been fired and that’s why we lurched,” she said. “Those torpedoes went under the ship.”

Finally, after 10 miserable days at sea, the Il de France pulled into harbor at Glasgow, Scotland. Greeting the women as they walked down the gangplank were their leaders, Major Charity Adams and Captain Abbie Noel Campbell. Lieutenant General John C.H. Lee, General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s logistics chief, and Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis, the highest-ranking African-American officer in the American Army, also showed up. More importantly, Red Cross women were there to serve them coffee and doughnuts. Pfc Johnson’s sea adventure had ended. Her land adventure had just begun.

Romay Johnson, from King George County, Virginia, east of Fredericksburg, enlisted in the U.S. Army at the age of 24. The only daughter of six children, she grew up in the country, surrounded by animals, particularly horses, dogs, and cats. Her five brothers, who called her “Sweets,” often excluded her from their play. “I was always by myself,” she said.

After graduating high school, Johnson wanted to be a doctor but saw no opportunity in that field. “I found out there was a lot of prejudice,” she said, “and they didn’t want me around.” Instead, she took a job operating an elevator in a hospital. Later, she worked for the Bureau of Engraving in Washington, D.C. Her job entailed placing paper on an inked mat that had been engraved for currency. She would then pick it up and wave it in the air while the ink dried. “I was making money,” she mused.

But the job offered no respite from racial prejudice. One day, a white coworker from Texas who did not like working with black women threw water over the ladies’ room stall Johnson was using (federal buildings did not segregate). “I was going to beat her up,” Johnson emphasized, “but I never got the chance to.”

Instead, on May 18, 1943, Johnson volunteered for the U.S. Army. “I quit to go with the boys,” she explained. Her five brothers had already joined the war effort. Her oldest brother Tom served with the United Service Organization (USO) in Hawaii, while Augustus had joined the U.S. Army before the war in an antiaircraft unit in the South Pacific. Johnson’s younger brothers also served. Preston joined the U.S. Navy, while Purcell and Stansbury joined the U.S. Marine Corps. Purcell served in the Central Pacific, but Stansbury never shipped out.

Johnson was sent to Fort Des Moines, Iowa, for basic training. The fort had originally trained white female officers but opened a segregated section for black female officers. By the time Johnson arrived, it was training enlisted women as well. Graduates would be part of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Most of the women, including Johnson, were scared when they arrived, not knowing what to do or what to expect. “We were all star gazing,” she recalled. She was fitted for a uniform and issued all her essentials. Her days were filled with calisthenics, marching, and learning to be a soldier. “It all went smoothly,” she said, “Everyone was new to everyone.”

She found the people at the fort friendly, and, since she was surrounded by Black women, she did not have to worry about the kind of prejudice she experienced at her last job. “I don’t think anyone felt cheated,” she said about enlisting. “No one thought they were mistaken by joining.”

Once she completed basic training, Johnson traveled to Camp Breckinridge, in Morganfield, Kentucky, where she was assigned to the motor pool. She learned about vehicles and how to change parts. “I had to be smart,” she explained. Having driven her family’s Vauxhall four-seater car back home in Virginia, she enjoyed driving officers around the post. “I liked to be outside and free,” she said. Once she got used to the post, it was smooth sailing wherever she went. Like many soldiers, she picked up smoking and enjoyed cigarettes while driving or waiting for her passengers. “When I was at the wheel I was smoking,” she said. “It was comforting for me.”

She only got into one accident. While driving the post’s provost marshal, a soldier driving another vehicle burst through a gate and broadsided her car on the driver’s side. Johnson’s head hit the window handle. “I got a lick on the side of my face.” Fortunately, the provost marshal, sitting on the other side of the car, remained calm throughout. “I commanded my car very well,” said Johnson.

In the motor pool, Johnson was put in charge of a jeep, two staff cars, a weapons carrier, and a truck she affectionately named “Cassandra.”

“I called them mine because they were assigned to me.” She spent her off hours reading, knitting and crocheting. “I never ventured out.” One day, someone gave her a black-and-white dog, which she loved to play with. “No one else wanted it,” she said. “I was a tomboy.”

Having grown up in the hardscrabble South, Johnson did not drink Coca-Cola and didn’t appreciate people asking her for money to buy their own. One day, a fellow WAC named Nancy bothered her for change for a Coke. “Johnnie, gimme a dime,” she asked. Johnson refused. Nancy kept asking and Johnson kept refusing. Then, Nancy got angry. “Go on, Johnnie!” Nancy threatened her. “Go on!” and shoved Johnson into the corner of a post. Johnson broke into tears. “I cried,” confessed Johnson. “I’m my momma’s baby.” Johnson went to retaliate against Nancy, but the other women in the barracks separated them.

One of the female officers entered and lectured the two women on their behavior. In another incident, while working, several women were very noisy, laughing loudly and playing in the workroom. The officers scolded them, but the women lied and blamed Johnson for the noise. Even though she strongly denied being a part of the noisy group, she was still reprimanded for defending herself because she would not stop talking. “I was so angry about that since it was not my personality,” said Johnson. “That’s how I lost my stripe.”

When Johnson learned that the Army was looking for Black women willing to go overseas for a war-related assignment, she volunteered. “Some of us wanted to go,” she recalled. She had to go through personality and character testing and training. Once she passed, she traveled to Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, for overseas training. After training, she and the unit took a train to New York City, where the women boarded the Il de France for the harrowing journey across the Atlantic.

When Johnson and the other Black WACs stepped onto Scottish soil, on February 12, 1945, they became the first all-Black, all-female WAC unit to serve overseas during World War II. Unaccustomed to African-American women in the war zone, the newspapers insultingly referred to them as “Tan WACs” and “Negresses.” A series of busses took the women to their new home in Birmingham, England—the former King Edwards Boys School. Because of Birmingham’s vital industrial and manufacturing centers, the German Luftwaffe had bombed it during the “Birmingham Blitz” from 1940 through 1943.

To drive home the realities of war, the women were given a tour of the city. “You could see the damage,” remembered Johnson. Their tour guides pointed out the places on the sides of the roads where dead bodies were stacked liked logs for pickup after the raids. “Those were the [body] parts they could find,” she said. “It was amazing what they had to endure.”

One month after their arrival, the women were organized into the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, tasked with catching up a backlog of mail, filling several warehouses, that had failed to reach soldiers in Europe for almost a year. The women were given only six months to clear the warehouses and process the mail. “We had to be on the ball,” Johnson explained. “We sorted that mail for different companies. We had envelopes for this service company or that headquarters company and we would send it off in bunches.”

The women went to work. Each of the battalion’s four companies worked one of three eight-hour shifts, around the clock and through the weekends. Unlike other Black units, the 6888th had no white officers, making it unique in the European Theater of Operations.

It was tough work. The windows in the freezing warehouses had all been painted black, to camouflage them from the Luftwaffe. Most days in Birmingham there was no sun since British winters were mostly overcast, cold, and damp. “I was too cold all the time,” said Johnson, even though she had been issued winter fatigues. “It was an icy cold that penetrated you.” Johnson, who had suffered bouts of pneumonia growing up, found herself sick with bronchitis. “I would get hoarse and cough and I shivered all the time.” She never got used to the cold. Her only relief came around noon, if the sun came out to warm things.

Under Major Charity Adams, the battalion kept a disciplined schedule. “She was strict,” said Johnson. “She had to be strict.” Adams did not hesitate to address a soldier if she acted up or was not doing her job. “She fussed at me because I wasn’t used to women and their particularities.”

Johnson made three good friends while in Birmingham, although in 2020 she could not remember their full names: Mamie Lewis, Barbara, and another girl she remembers as “Butch.” Mamie was a scrawny but lively four-foot-tall woman. “She was always asking me, ‘Johnnie, whatcha doing?’” said Johnson. Barbara was fun, while Butch was a tall, skinny, fair-skinned woman who liked to see how other people lived. “She was just my speed,” explained Johnson.

But Johnson did not get along with all the women in the unit. “Some did mischievous things,” said Johnson. “They would tease each other and make noise.” One day, when the women got too loud in the mail sorting room, an officer marched in and the women said, “Johnnie did it!” The officer looked at Johnson and told her to be quiet. “The women called me ‘crybaby,’ I wasn’t used to rough women,” said Johnson. “I was trying to keep them quiet.” When she later complained to the officer, the woman told her she would get used to it.

For enjoyment, Johnson spent her free time visiting a local family that had a five-year-old son. They would invite her over for dinner and she would play with the boy. He showed her how to draw ducks and taught her how to dress figurines in muslin fabrics.

Although the war in Europe was winding down, world events could still shake the women. On April 12, 1945, the women of the 6888th were hit with the heartbreaking news that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had seen the United States through the Great Depression and darkest days of World War II, had died. “We knew he was sick,” said Johnson, but we didn’t want him to die.” Two days later, on April 14, the unit held a special formation and a memorial prayer for the fallen president. “We were very sad.”

The sadness of mid-April was replaced by sheer joy in May 1945, when the Germans surrendered to General Dwight D. Eisenhower at his headquarters in Reims, France. The war in Europe was over. “Everybody was pleased and excited,” explained Johnson. “I thought about the number of people killed and those [people in Birmingham] left on the side of the road.”

Soon after the surrender, the 6888th completed its mission. They had accomplished their six-month assignment in only three months. The battalion had done it by maintaining an average output of between 60,000 and 70,000 letters and telegrams per day. More women had arrived to help process the mail, so that by the time they were done the unit numbered 848 WACs. Johnson and the rest of the 6888th proved that Black women would pitch in and help their country during a global crisis.

Even though the war in Europe was over, there were still two million Americans on the continent who needed their mail. The women were given a new job and new location. They were sent to France, this time to redirect mail for soldiers, not only those in Europe, but also those who had already returned home since VE Day, referred to as “SNAFU” G.I. mail.

When the women walked down the gangplank in Le Havre, France, on their way to Rouen, a battalion of African-American soldiers greeted them, sparking hundreds of reunions between brothers and sisters, husbands and wives, cousins, fiancés, and a father and daughter. Since Johnson’s brothers were serving in the Pacific, she had no reunion. Once in Rouen, Johnson witnessed the effects of modern combat on an ancient city. “It was horrible,” she said. “There was nothing but shell holes and only some trees standing.”

The women were housed in the Saserne Tallandier, a former French barracks. They went to work again to break up the logjam of mail and packages. The experienced women again accomplished it in three months. With their task complete, the war over, and most Americans heading home, Johnson and the rest of the 6888th headed to Paris to await their turn to head home.

Johnson enjoyed Paris, with its cafes and museums. “I remember almost living in the museums,” she said. “I could speak a little French.” While sightseeing in Paris one day, Johnson saw General George S. Patton, Jr. The general’s staff car, escorted by a pair of motorcycles, had stopped at an intersection. Someone pointed the women out to Patton and explained who they were. “He greeted us,” said Johnson.

Johnson took advantage of her time in Europe by visiting Switzerland for a few days with her friend Butch. She further took advantage of the opportunities the U.S. Army provided by taking courses in fashion design so she could go home with a skill.

Johnson returned by ship to New York harbor, where one of her brothers met her and drove her to her Aunt Lola’s house in Harlem. “She was screaming that I was home,” recalled Johnson, “and she asked all kinds of questions.” Johnson found herself repeating stories to her aunt more than a dozen times. The reunion was not all happy. When Johnson went out to her brother’s car, she found that someone had stolen her Army foot locker. “I had everything stolen from me!”

Johnson returned to her parents’ home in Virginia, where she reunited with her brothers. They all came home safe, except for Purcell, who returned from Japan with chemical burns on his skin. “He had been a big hunk of a male,” said Johnson, “but he would get very ill and his skin would peel off.” For treatment, they covered his skin with mesh screens that Johnson thought looked like mosquito nets. “He suffered tremendously and we couldn’t touch him.”

Johnson took advantage of the GI Bill to attend the New York Fashion Institute, where she encountered some intolerance. “The pattern maker didn’t like me,” she said. “They never had people like us before in their classes.” Later, she spoke with a Jewish man who owned his own shop, making jodhpurs (polo pants). They discussed pattern making, and he thought she would enjoy learning how to make patterns. He recommended she attend the Traphagen School of Fashion near Times Square. She took his advice and graduated in three years.

In 1953, she took a job at Glen of Michigan, a children’s-clothing manufacturer in New York City. “I did the designing and patternmaking.” She also traveled the country, buying fabrics and obtaining fashion ideas.

While working in New York, Johnson attended a party where she met a man named Jerry Davis, a carpenter for the New York subway system. They soon fell in love and, in 1957, married. “He taught me how to laugh,” said Johnson. They remained married for 42 years, until Jerry passed away in 1999.

After 30 years with Glen of Michigan, Johnson went on to make suits for a Florida couple based in New York for another five years. While working, Johnson constantly sought to improve herself. In 1959, she gave up smoking. She earned a Master’s degree in Education from New York University in the 1970s. She taught herself taxidermy, worked as a real estate agent, built furniture, and learned to paint things other than ducks. At age 78, she earned a second-degree black belt in taekwondo.

As a member of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, Johnson was a pioneer, helping to lay the path for future generations, making the Army the diverse reflection of America it is today. At age 101 in 2020 and retired in Montgomery, Alabama, Johnson looked back on her service in World War II with pride.

“I enjoyed my service,” she said. “Everyone should have the experience to know what it was like to be in the military.” But for all experiences in Europe during World War II, it was that Atlantic storm she remembers most. “I will never, never, forget that experience.”

Kevin Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Army. He is the author of Patton’s Photographs: War As He Saw It. He leads tours of General George S. Patton’s European battlefields for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. He has written several articles on the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion.