By Alice Flynn

Ordered to “hold at all costs,” 300 American soldiers defended the small Luxembourg town of Hosingen during the first three days of the Battle of the Bulge. They were surrounded and outnumbered more than 10 to 1, bombarded by tanks and artillery that set most of the town on fire, and given no aerial or artillery support. They were abandoned by the 28th Infantry Division’s other units but managed to hold out for 2½ days until they ran out of ammunition, sacrificing themselves for time. Stranded miles behind enemy lines, they had no choice but to surrender and would be forced to endure the unimaginable to survive as prisoners of the Nazis.

Landing on Omaha Beach on July 25, 1944, the 28th Infantry Division (ID) entered into its first combat near the town of St. Lo on July 30. As the 28th fought its way across France, it earned a fierce reputation among the German troops. Mistaking the former Pennsylvania National Guard unit’s red Keystone emblem as a “Bloody Bucket,” they believed the insignia reflected the toughness of the unit’s fighting ability, and the name stuck.

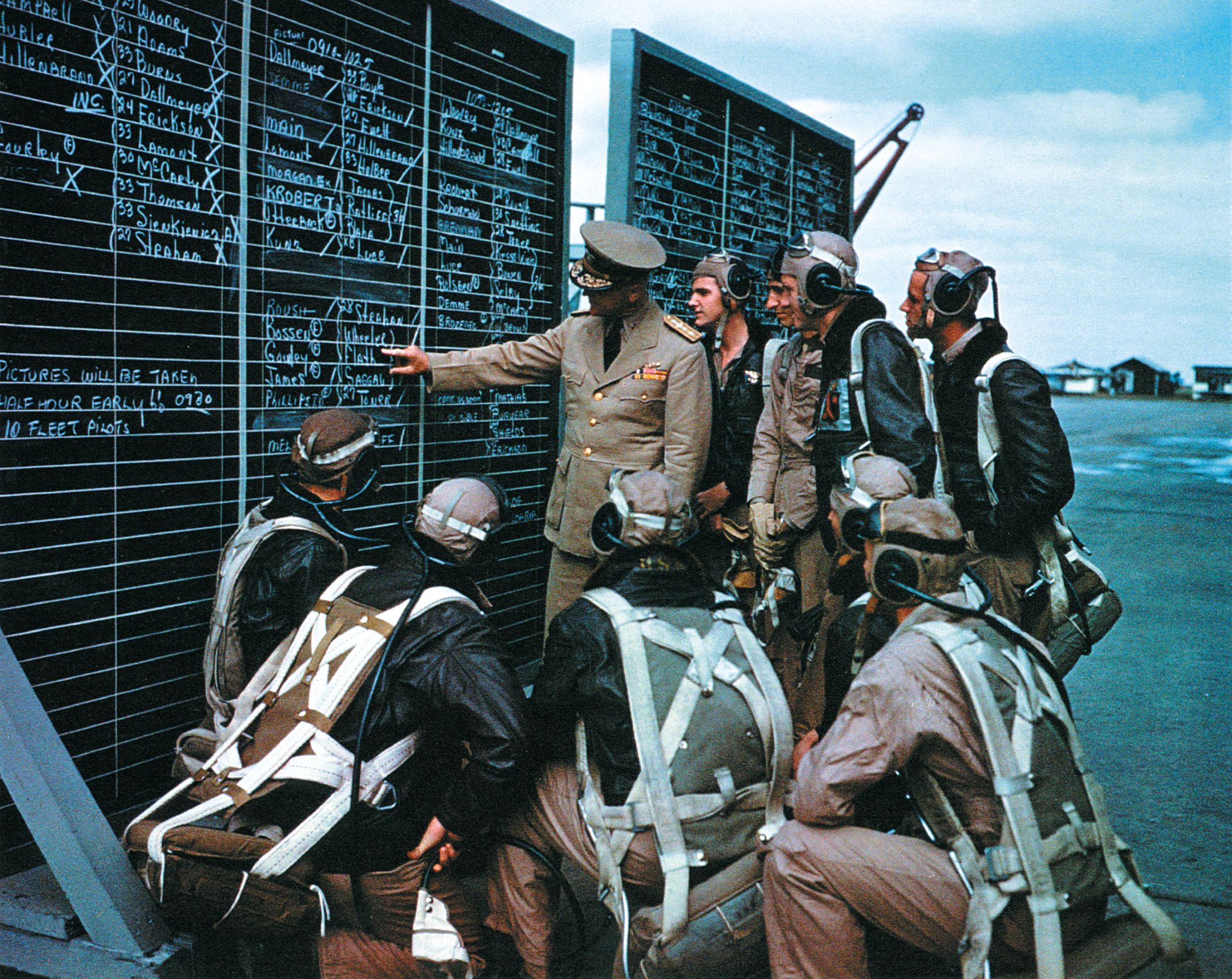

On August 13, Maj. Gen. Norman Cota was assigned to take over the unit, and it advanced much more quickly but suffered substantial losses along the way. On August 25, it reached the city of Paris, and the 28th ID was selected to represent the U.S. Army in a victory parade, passing through the Arc de Triumph down the Champs-Elysées to a cheering Parisian crowd. Eight hours later the 28th was back fighting remnants of German units just outside the city limits.

Throughout September, the division continued to push the Germans across France and swept through Belgium, averaging 17 miles a day against heavy German resistance. The 28th became the first Allied unit to reach the German border on September 11. After two months of fighting, the unit was sent to the rear on October 1 for rest and recovery. Thousands of replacement troops were added over the next month to fill out their depleted ranks, many of whom would fight their only battle of the war once they reached the Hürtgen Forest. The battle-seasoned veterans did not even want to know the new GIs’ names because they knew many of them would be killed in action or wounded once they started fighting.

Replacing the 9th ID in the Hürtgen Forest on November 2, the 28th ID lost many soldiers to machine-gun fire from well-positioned German bunkers, antipersonnel mines, mortar attacks, and tree bursts that took a devastating toll both mentally and physically. Freezing weather, a foot of snow, and no winter gear also had a significant impact on the troops as many of the GIs would suffer from severe frostbite and respiratory illnesses. From November 2-14, the 28th ID reported a total of 4,939 casualties, of which 4,238 were infantrymen.

Half of those casualties can be attributed to the 110th Infantry Regiment (IR), whose original strength was 3,202 men. The regiment saw 65 men killed in action, 1,624 wounded, 253 taken prisoner, 288 missing, and 86 men with non-battle-related issues, totaling 2,316 casualties.

K Company’s casualty rates were among the highest within the 110th with 21 of the regiment’s 65 men killed. By mid-November, there were just six men left in K Company, which had been part of the original landing forces in July.

Relieved by the 8th ID on November 14, the 28th was once again sent to rest and rebuild in the quiet section of the Ardennes Forest, just 60 miles to the south. K Company, 110th IR was reassigned to Hosingen, Luxembourg. Fewer than 20 men had survived the Hürtgen Forest action, and only 20 combat veterans returned to duty during the month. The balance of K Company’s strength of about 160 men was nearly 100 percent replacements.

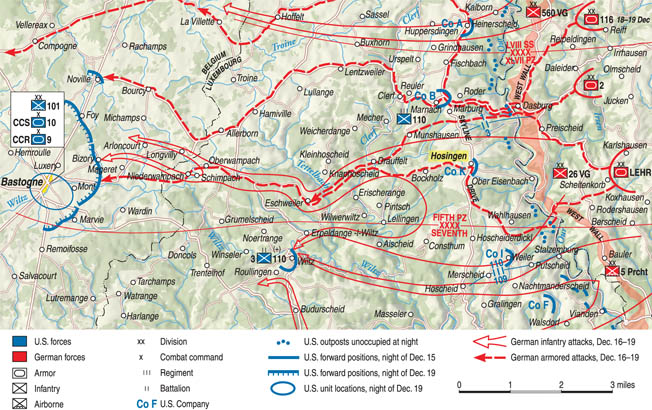

Hosingen was four miles from the German border and in the middle of five company strongpoints assigned to the 110th, within a 10½-mile sector along the ridgeline. The Ober Eisenbach-Hosingen-Drauffelt road ran from the Our River, the border with Germany, to Bastogne, Belgium, crossing two bridges over the Clerf River at Drauffelt and Wilwerwiltz. Because military intelligence was confident the Germans were not able to mount any kind of a major offensive, the units stationed along the front line were allowed to pull back into town each night.

K Company was supported by the 2nd and 3rd Platoons of M Company, 3rd Battalion’s heavy weapons company, and 2nd Platoon of the 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion with three 57mm antitank guns and three .50-caliber machine guns guarding the crossroads south of Hosingen on Steinmauer Hill.

Also in the town were 125 men with Captain William Jarrett’s B Company, 103rd Engineer Battalion, who were responsible for road maintenance to get the units where they needed to go. This unit had at least eight .50-caliber machine guns mounted on trucks. Lastly, there was a group of 20 men from a “raider” unit (organization unknown) who had come in for specialized training in scouting and patrolling. Altogether, there were 387 enlisted men and 13 officers assigned to the Hosingen garrison.

Having taken command of K Company on November 8, 1st Lt. Thomas J. Flynn was responsible for his company establishing the defensive perimeter around the town. His officers immediately began to train the replacement troops; many had arrived with no combat training. Flynn was concerned that normal supply runs delivered only one day’s supply of ammunition for training.

Former company commander Captain Frederick Feiker returned to duty on December 6, and Flynn became his executive officer.

Throughout December, K Company observed increasing indications that something was developing on the east side of the Our River, but their commanding officers (COs) failed to take their intelligence seriously.

What the Allies did not realize was that Hitler was preparing for a massive counteroffensive that would once again come through the Ardennes Forest as it had four years earlier. Hitler did not expect the 110th to put up much of a fight, so he planned an offensive right through the middle of the regiment. By mid-December, he had accumulated 250,000 soldiers, hundreds of tanks and self-propelled weapons, and thousands of support vehicles for his massive assault.

The 26th Volksgrenadier Division (VGD) was considered the best infantry division of the Fifth Panzer Army. Twelve thousand men strong, the division was to capture all the positions held by the 110th. Critical to the plan was that Hosingen needed to be captured on day one. An entire battalion was assigned the task to ensure success. From there, the grenadiers were to seize control of the bridges over the Clerf River and then move on to capture Bastogne by the end of day two on their way to the port of Antwerp. Any delays might give the Americans enough time to move additional fighting units to Bastogne to defend the critical crossroads city.

On the evening of December 15, K Company’s southern outpost (OP) picked up the sounds of what were believed to be engines coming from the direction of the Our River. Shortly thereafter, the men in Hosingen observed the Germans shining searchlights into the night sky, their reflections bouncing off the low winter clouds and lighting up the entire area almost as brightly as daylight. As a precaution, Captain Feiker ordered the company’s mortars moved to new positions, which would prove to be an important tactical decision.

Around 0300 on December 16, elements of the 26th VGD began quietly crossing the Our River in rubber boats, hidden by a thick blanket of fog. Once in position, the German units waited for the artillery bombardment that would signal the beginning of the offensive.

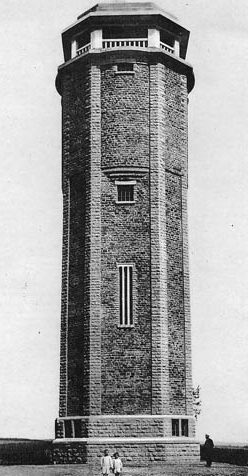

At 0530 the GIs in the OP atop the water tower in the northeast corner of Hosingen had just called their CO when they observed hundreds of “pinpoints of light” to the east. Seconds later artillery shells exploded throughout the town and the surrounding area, severing all wire communications.

Every man in K and M Companies was sent to his prepared defensive position. M Company’s 2nd Platoon and K Company’s 3rd Platoon were defending a position at the Hosingen-Barrière intersection 1.5 kilometers south, and a squad from the 630th’s 2nd Platoon was on Steinmauer Hill, 200 meters south of the village, leaving just 300 men in the town. Both of the outlying locations were now cut off and on their own.

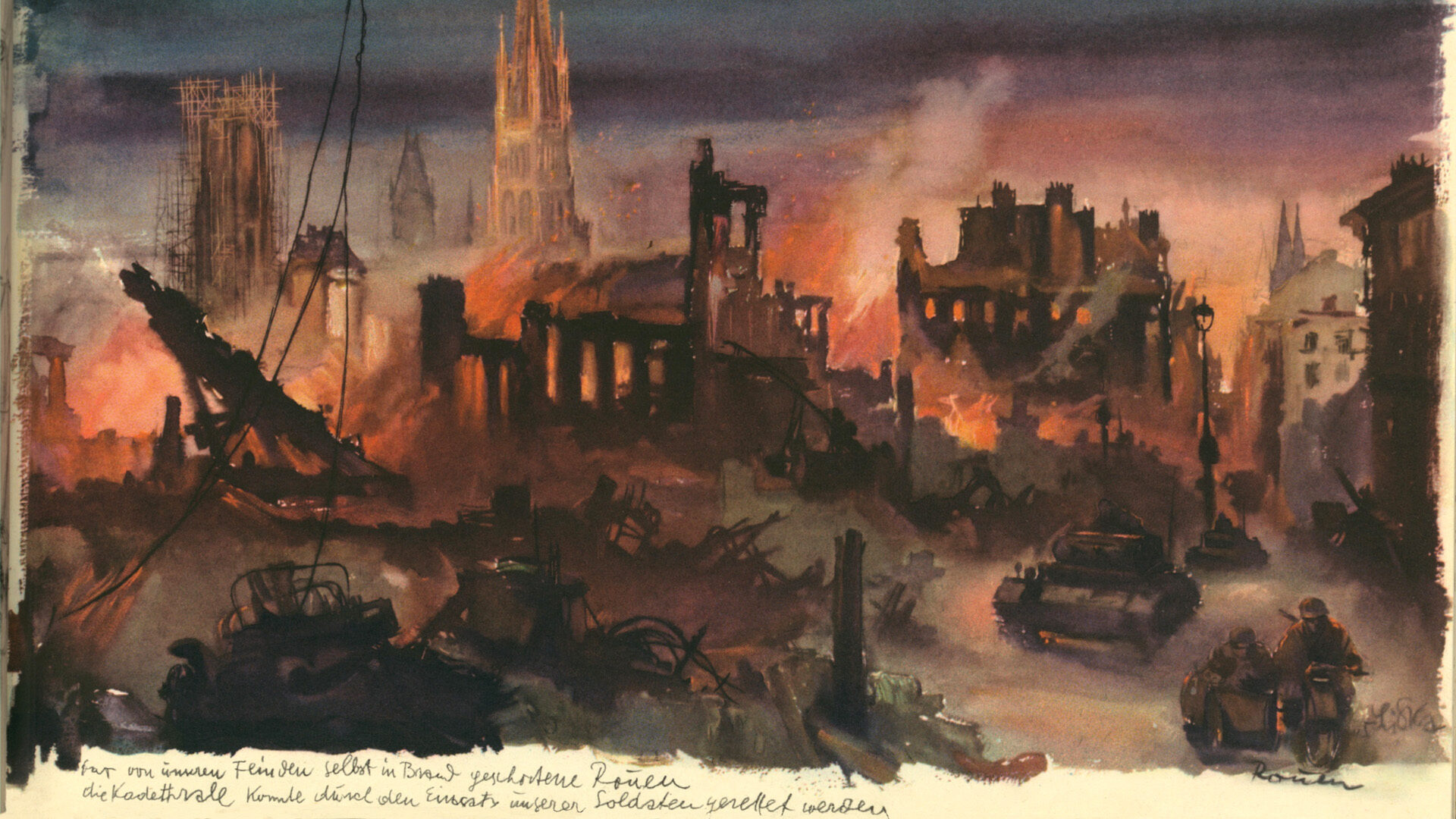

Private William Gracie and the other soldiers of K Company’s 4th (heavy weapons) Platoon scrambled out of their beds, grabbing their weapons as they ran out of the house they had called home. Their foxholes near 1st Platoon’s northern OP were not far away, but yesterday’s snow melt had left them partially filled with water and ice. Lieutenant Flynn jumped in a foxhole behind 1st Platoon machine gunners, and Lieutenant Bernie Porter joined 2nd Platoon on the south end of town. The initial artillery barrage had already set five buildings on fire. “The town was pretty well lit up,” Flynn recalled, illuminating the whole ridgetop.

By the time the shelling ended 45 minutes later, two more buildings had caught fire, and it was noted that artillery had fallen in each position where the company mortars had been located just a few hours before, but no casualties had been suffered among the defenders. The sound of troops moving could be heard to the north, but it was still too dark to see.

At daylight, the GIs could make out shadows in the distance, so Flynn ordered his men to open fire on the Germans crossing Skyline Drive. Sergeant James Arbella, 60mm mortar section leader of K Company, climbed the water tower and gave 4th Platoon mortar crews coordinates to targets along Skyline Drive. The combination of mortar shells, Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), machine-gun, and rifle fire shattered the German assault. The surviving Germans retreated, leaving behind scores of dead and wounded.

An initial rush of the 77th Grenadier Regiment overran the OP on Steinmauer Hill and cut off those units south of the village. Some of these American troops were able to retreat to the west, while others continued to fight on until killed or captured.

Captain Jarrett had gone up the village’s church steeple to provide Lieutenant James Morse’s M Company 81mm mortars with coordinates of another assault from the south. The mortars temporarily halted this German movement. Captain Feiker requested artillery support, but Battery C, 109th Field Artillery Battalion, located due west of the ridge, was also under attack and unable to respond. The village’s defenders only had their own mortars for support as Captain Jarrett’s engineers had not yet joined in the defense of the town.

German troops managed to enter the southern outskirts of Hosingen. A German officer was captured with a map outlining their attack plan all the way to Bastogne. Surrounded and grossly outnumbered, it was already impossible to get the map to regimental commander Colonel Hurley Fuller in Clervaux. Feiker then contacted Major Harold Milton, 3rd Battalion CO in Consthum, to inform him of the situation. Milton told Feiker that they were to hold their position and promised to send L Company, in reserve near the CP, with ammunition. However, L Company became involved in its own fight and was never able to reach Hosingen.

In spite of heavy damage to the division’s communication system, sufficient information had reached Colonel Fuller and General Cota for them to realize that the 110th was facing a massive German assault and that most of their frontline positions were surrounded and cut off. Cota ordered Fuller to have his regiment “hold and fight it out at all costs.” Cota then ordered Companies A and B of the 707th Tank Battalion to head for Clervaux to support the 110th.

Despite their inability to communicate with Captain Feiker, the GIs defending the southern OP at Hosingen-Barrière were still very much a fighting unit because the initial German artillery barrage had missed its target. The GIs defending the southern OP at Hosingen-Barrière had repelled the initial assault on their position and had captured three German officers. Machine gunner Private Dale Gustafson was ordered to guard the prisoners in a barn.

Feiker was concerned that the enemy might next attack from the west, so Major Milton ordered Jarrett to follow Feiker’s orders. Engineer Lieutenant Cary Hutter and 1st Platoon dismounted their .50-caliber machine guns from their vehicles and moved into position to defend the west side of Hosingen supported by M Company’s mortars. The engineers shared the 3,000 rounds each of .30-caliber and .50-caliber ammunition they had with K Company. Connecting eight land mines on a daisy chain, the engineers ran it across the street, hoping it would snag onto the first tank to enter from the west end. They also sent Private Frank Kosick up the church steeple with his bazooka.

Lieutenant John Pickering and 2nd Platoon helped cover the southern half of the town, supporting Captain Feiker’s command post and the south roadblock. The 3rd Platoon, under Lt. Charles Devlin, was positioned along the northeast edge of town to provide fire support to Flynn’s 1st Platoon, helping cover both the north roadblock and the men from K Company in the water tower. Captain Jarrett’s CP was in the Hotel Schmitz in the center of town. Each team was then responsible for adding mines on all roads that entered Hosingen.

At 1515 hours, 1st Lt. Richard Payne led the 3rd Platoon, A Company, 707th, south along Skyline Drive from Marnach. With machine guns blazing, at about 1600, Payne’s tanks entered the north end of Hosingen to the cheers from the 1st and 4th Platoons. Payne scrambled to get his tanks into defensive positions. Three tanks, accompanied by infantrymen, were sent to retake Steinmauer Hill to help slow the enemy traffic coming up the Ober-Eisenbach road. Payne moved his own tank to cover the road south of the village. The remaining Sherman was positioned to cover Skyline Drive to the north.

At 1600, German pioneers finished construction of the bridges over the Our River at Gemünd, Dasbürg, and Ober Eisenbach, enabling the German armor to cross. The Americans in Hosingen were proving to be much more difficult to eliminate than expected, so at 1700 General Heinz Kokott ordered three panzers from the Panzer Lehr Division and part of his division reserve, the I Battalion, 78th Grenadier Regiment, to help attack the town. Two German panzers appeared on the high ground on Steinmauer Hill and forced the three Shermans to withdraw into Hosingen; however, they spent the evening lobbing shells at the Germans and then racing back to cover.

West of the tower, Sergeant John Forsell, a 1st Platoon squad leader, watched his machine guns lay down devastating fire. The fighting continued all night with small groups of Germans infiltrating the village. Vicious and often hand-to-hand fighting continued until around 2200. Lieutenant Flynn became involved in one of these skirmishes, killing a German officer. Flynn reported to Feiker that he had found documents on the German’s body.

As the fighting died down, German patrols continued to work their way to the edge of the village. Amazingly, there were few American casualties. The men could see two other towns to the north and northwest burning brightly during the night.

General Troy Middleton, commanding the U.S. VIII Corps, finally realized the Germans had attacked along his entire 80-mile front and his 4½ divisions were facing four times that number of German divisions. Middleton knew the only option was to delay the Germans as long as possible to allow time to move reinforcements into the Ardennes, and particularly to the key crossroads town of Bastogne. Middleton reiterated that the 28th was to “hold at all costs,” especially the 110th, the major unit directly between the Germans and Bastogne.

As daylight approached on December 17, the Germans renewed their attacks, and additional Mark V Panther and Mark IV medium panzers were diverted south to help rid the village of the stubborn Americans.

At Hosingen-Barrière, a shell from a tank blew a hole through the wall of the barn, knocking Private Gustafson down. A few seconds later, a second blast hurled a heavy iron cauldron from the fireplace at his head, knocking him unconscious. By the time he awoke, his platoon had been captured. The German officers Gustafson had been guarding ordered the grenadiers not to kill the Americans because they had been so well treated.

By 0900, German tanks showered Hosingen once again with artillery, setting more buildings on fire, including Hotel Schmitz. Captain Jarrett was forced to move his CP to the basement of a nearby dairy to the west.

As the artillery fire ended, another German ground assault began, but the GIs continued to fight back, their mortars taking out three enemy tanks with two more already on fire. Small-arms fire could be heard throughout the town. Antitank mines exploded as the Germans wandered into the engineers’ well-laid minefield. Fallen grenadiers that had not yet been removed from the battlefield were crushed under the tracks of their own tanks as the Germans made their way toward the edge of town. The fighting lasted for another hour before they pulled back to their starting positions in frustration.

Captain Feiker got a radio call through to Major Milton asking for artillery support, but he was informed that the 109th had been forced to retreat across the Clerf River. They were on their own.

The Germans then sent two half-tracks as decoys down Skyline Drive in an attempt to trick the Americans into giving their northernmost Sherman’s position away, but Flynn and Payne’s men held their fire. The GIs in the water tower then sighted two Panthers hiding to the northwest in a position from which they could have blasted the Sherman had it revealed its location.

At 1300, the two Panthers opened fire on the tower, cutting the telephone line and leaving K Company with no communication with the GIs still there. Contact with the water tower had to be restored, so with a new wire in one hand and his rifle in the other, Sergeant Lloyd Everson ran several hundred yards to the water tower, bullets frequently kicking up the snow beside him as he ran. Everson managed to connect the new wire and went inside to make sure the phone was live.

Six more Panthers and Mark IVs from the 2nd Panzer Division arrived from Marnach. A total of eight German panzers now worked their way to the north edge of the village. Captain Feiker tried to send bazooka teams to drive off the Panthers, but the German small-arms fire was too heavy to move beyond the edge of the village. The fighting continued all afternoon. Germans who managed to reach the village were engaged in hand-to-hand fighting. Houses, shops, and hotels were slowly and methodically being reduced to rubble. The Germans finally destroyed 1st Platoon’s machine guns and mortars, and even rifle ammunition began to run out.

The water tower went next. Once inside, Sergeant Everson found a wounded lieutenant and a couple of his men. He knew that they would make their last stand in the tower. Climbing the stairs, he looked out the window. The enemy was moving in, infantry supported by tanks. Everson began exchanging fire with them. He could feel the heat of the German bullets as they passed by his face and then sizzled in the snow on the floor.

A tank then fired two rounds at the tower, and both exploded outside. Not satisfied with the results it was getting, the German tank moved to a position a little farther away, turned, and swivelled the gun at the tower. Everson kept firing at the German soldiers, watching the tank out of the corner of his eye. The tank reared back and fired its next shell at the tower just as the empty clip flew from Everson’s rifle. The impact blew him down the stairs.

Everson lay stunned on floor unable to see or hear, but he felt the concussion of the next shell hit. His mouth was filled with the taste of cordite. He popped his eardrums so he could hear, blowing his nose while holding it shut with his hand as he rubbed his eyes, forcing tears, only to see a German machine pistol pointed at him. A medic bandaged the lieutenant’s and Everson’s wounds before they were taken away. Everson looked at his watch a few minutes later—it was 1615 hours.

Lieutenant Flynn’s 1st Platoon CP could see what was unfolding at the water tower, but his men were dealing with their own problems. Flynn’s radio had been damaged, so Feiker had no idea what was happening on the north end of town. Flynn needed to report 1st Platoon’s situation, so he ran the gauntlet from his position 650 meters south to Feiker’s CP, dashing from cover to cover through the rubble-strewn streets of Hosingen. One of the German tanks spotted Flynn and started shooting directly at him, but its position did not enable it to lower its aim enough. He dodged the German gunfire and shell bursts all the way through town to Captain Feiker’s CP in the pharmacy building near the center of town.

By dusk the Germans were inside the town, and the fighting continued house to house and hand to hand. Gradually, most of the men worked their way back to the center of town, but there were small groups of men now cut off and isolated. When forced to withdraw, the GIs set booby traps to inflict casualties and start fires. The fires also helped to light up the fields around the village, exposing the Germans to gunfire. Despite the GIs’ efforts, the Germans pressed forward, and their numbers in the village continued to grow.

Captain Feiker met with his officers to assess the situation. There were small pockets of GIs cut off, their ammunition almost gone, and there were only three operating tanks. There was no artillery support or relief force on the way. Payne’s Shermans set up a perimeter defense around Feiker’s CP.

At 0200 hours on December 18, a group of 16 grenadiers stormed Jarrett’s CP, but his men repelled the attack. Jarrett sent a Lieutenant Slobodzian to check on 3rd Platoon’s position, but he was shot in the left arm and left leg before he could do so. Several men carried him to the aid station in the town church, where his best friend, Corporal John Putz, B Company’s medic, did his best to take care of him and keep him alive, but he had lost a lot of blood. Corporal Putz applied a tourniquet to stem the bleeding and administered morphine, but Slobodzian was already in a state of shock. It was now 0300 hours. There was no more plasma available, and both Slobodzian and Sergeant Lawrence Gronefeld, who had been shot in the upper thigh the previous day, were sinking fast.

The fight continued, and enemy fire from the west was now being directed at the church where K Company’s Staff Sgt. Norman Guenther and Master Sgt. Joe Winchester’s engineers were protecting the wounded. Jarrett had his men cover him from the dairy while he worked his way close enough to throw a hand grenade over the side street wall, where the shots were coming from. By now, the majority of the buildings in the town were on fire, and the heat was almost unbearable despite the freezing temperature outside. Most of the American vehicles had already been destroyed.

At 0430 hours, Feiker once again spoke with Major Milton, explaining K Company’s situation and asking for instructions. Milton finally ordered the men to try to escape while it was still dark, but Feiker said it was too late. “We can’t get out, but these Krauts are going to pay a stiff price….” Major Milton then told Feiker that he and his men should do whatever they saw fit.

Feiker promptly called together his officers. They all agreed that there was little chance of escaping through the German lines. The mission of delaying the enemy had been carried out, but they were now entirely surrounded and were no longer delaying the German advance.

Lieutenant Flynn recommended that they surrender so the men would have a better chance of survival, wishing not to repeat what had happened to K Company in the Hürtgen Forest. Feiker conceded, and the other officers agreed. Feiker then issued the order that all remaining weapons and materials that would be of any value to the enemy were to be destroyed. In response, Flynn removed his.45-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver from its holster and destroyed it. He then laid the useless revolver on the table, turned, and left the room to get started on the rest of the demolition.

Feiker briefed Jarrett on the situation and asked for his help with demolition. All remaining maps, records, vehicles, and equipment were set on fire or rendered useless. All weapons were destroyed, ensuring that the same part of each type of weapon was damaged so that the Germans could not rebuild any of them.

Feiker then radioed Major Milton to tell him of their decision. Milton signed off by saying, “You have done your job well. Good-bye and God Bless You.”

By 0900 hours, German snipers and panzers once again began to fire on Hosingen. Feiker and Jarrett had a white flag hung from a building on the north end of town and white panels hung on the Shermans. The Germans ceased fire immediately. The two captains walked out into the open field together to surrender to a colonel from the 78th Grenadier Regiment.

Just before Feiker and Jarrett returned at gunpoint at 1000 hours accompanied by German troops, Lieutenant Morse radioed news of the surrender to Major Milton’s command post. “We’re down to our last grenades. We’ve blown up everything there is to blow up except the radio and it goes next.” What sounded like a sob came over the radio, but after a brief pause to compose himself he continued, “I don’t mind dying, and I don’t mind taking a beating, but I’ll be damned if we’ll give up to these bastards.” Then the radio went dead. Lieutenant Morse had ended the conversation by shooting the radio with his .45-caliber pistol.

Major Milton sagged in his chair and glanced at his watch. It was 0955. His men at Hosingen had held out five hours since their last call, and now they were gone.

The GIs were ordered to come out with hands on their helmets and to assemble in front of a nearby church. Staff Sgt. Norman Guenther was hesitant to go outside. Private William Hawn had fainted, but others were not allowed to help him outside. The Germans then entered the church, and the GIs heard Private Hawn’s screams. No one saw him after that.

The Germans were surprised when the American defenders gathered in the street. They could hardly believe that such a small unit had put up such a fight against their superior forces yet suffered so few casualties while inflicting such enormous damage on their own forces.

All the American officers could do was watch in silence as their men were yelled at, slapped around, searched, and stripped of their valuables. Enlisted men were forced to give up their combat shoes or galoshes in exchange for the inferior German boots of the soldier doing the trading.

A group of Germans mounted two MG42 machine guns pointed directly at the American POWs. An accidental discharge killed two men, and Private John Wnek was wounded in the forearm. The German captain reprimanded the machine gunner responsible for the shooting. Captain Jarrett later reflected that the German captain had saved many GIs’ lives that day by stopping a potential massacre.

Corporal Sam Miller avoided being shot by jumping behind the blade of a bulldozer parked nearby. A German soldier quickly had a gun pointed at his head to force him back into the lineup. The Americans could not help but stare at the lifeless bodies on the ground, the pools of blood slowly growing larger underneath them.

The American officers were separated from the enlisted men and marched to an isolated house at the south end of Hosingen, where they were searched and interrogated. One by one, each officer was required to empty his pockets into his helmet so a German officer could inspect each item. Lieutenant Flynn spoke German, so he served as an interpreter when needed. The interrogation took approximately an hour as the Germans were primarily concerned with details about the locations of minefields and booby traps.

At the same time, some of the enlisted men were marched around the corner of the church out of view and lined up in a nearby drainage ditch, machine guns on each end and two bulldozers waiting nearby. They all knew what was going to happen. They were going to be executed and buried right where they stood. Fortunately, a German staff car drove up and the officer stood up and yelled at the German sergeant to get the prisoners out of the ditch. The Americans climbed back onto the road and were marched to a field on the east side of town, where they would wait for more prisoners to join them.

Happy to still be alive, Sergeant Winchester whispered to Corporal Miller, “We put on a heck of a show, didn’t we?”

The rest of the enlisted men had been moved out into the open fields around the town to tally and search through the dead and wounded while the officers were being interrogated. Medic Wayne Erickson and Staff Sgt. George McKnight were forced to help bury 300 dead Germans. When finished, they were ordered to help take care of the wounded prisoners until transportation to a hospital could be arranged for them.

While the weather conditions had grounded most planes over the past few days, a spotter plane’s report of the intense shelling at Hosingen the day before had prompted several American fighter planes to be sent to the area for air support to help defend the town. From out of nowhere, the American planes flew in low and opened fire on the American POWs, mistaking them for German soldiers and unaware that the men of Hosingen had surrendered that morning and were being held in the open field below.

German planes were not far behind, having pursued them all the way from Bastogne, and the prisoners witnessed a dogfight directly overhead. One of the American planes was hit and set afire, but despite the plane’s rapid descent en route to a crash landing its machine guns were still firing and some of the prisoners in the field were killed. The plane crashed and exploded into flames, close enough to observe that no one made it out alive.

Around 1500 hours, the POWs were marched to Eisenbach on the Ober Eisenbach-Hosingen-Drauffelt road. Even after three days the road was still jammed with westbound traffic in support of the massive German offensive. The POWs arrived at Eisenbach an hour later and were jammed into a small church, where they lay tightly packed together on the floor and pews with only straw to cover them. Captain Jarrett, selected as senior officer of the group, was removed by the Germans and marched off for further interrogation. The prisoners tried to get some sleep as most had not slept in three days.

Erickson and McKnight were not fortunate enough to sleep indoors that night and would spend most of the next four months on forced marches back and forth across Germany until their liberation on April 12, 1945, near Horsingen, Germany, a journey of over 900 miles.

There were 23,000 Americans captured during the Battle of the Bulge. Because of this massive influx of prisoners, the GIs were split up once they reached the train stations. The POW camps were divided into stalags for the enlisted men and oflags for officers.

Camps where most of the men were held included the following: Stalag IXB at Bad Orb, Germany (enlisted men); Stalag IVB at Mühlberg, Germany; Oflag XIIIB at Hammelburg, Germany (officers); Stalag VIIIA at Gorlitz, Germany; Oflag 64 at Szubin, Poland ; Stalag 9A at Ziegenhain, Germany (noncommissioned officers); Berga Am Elster at Gera, Germany (slave labor camp).

Many of the men from Hosingen were first shipped to Stalag IXB at Bad Orb. On January 11, 1945, the officers were moved to Oflag XIIIB at Hammelburg. After the officers left, 300 American Jewish soldiers and 50 non-Jewish NCOs chosen at random were separated within the camp. On January 25, another 1,200 noncommissioned officers were relocated to Stalag IXA at Ziegenhain.

On February 8, the 350 Americans that had been separated within the camp were shipped to Berga Am Elster slave labor camp near Buchenwald concentration camp and were put to work digging tunnels for an underground ammunition factory. Private Clifford Williford of M Company was part of this group. This camp had a 20 percent fatality rate and represented six percent of all American POW deaths during World War II.

Out of a force of some 300 American defenders in Hosingen when the Battle of the Bulge began, just seven were killed and 10 wounded. The defenders had inflicted an estimated 2,000 casualties on the Germans, including more than 300 killed.

Hosingen was the last town held by the 110th Infantry to fall, giving the U.S. First Army time to rush troops to Bastogne on December 18, 1944, including the famed 101st Airborne Division. The story of the defense of Bastogne would have been much different if the 110th had not successfully carried out its orders.

The brave men who fought in Hosingen would never come together as one group again. Their “hold at all costs” order resulted in their suffering unimaginable hardships until they were either liberated or died as prisoners of war. They would all lose at least 25 percent of their body weight due to starvation, illness, disease, or wounds left untreated. Most would be locked in boxcars for days at a time, where they were bombed and strafed by Allied planes unaware they were locked inside. Many were forced to march hundreds of miles from camp to camp during the coldest winter on record. Only a few managed to escape.

After liberation by the Soviet Red Army at the end of January 1945, 110th Regiment commander Colonel Hurley Fuller nominated his unit along with the 109th Field Artillery Battalion and Company B, 103rd Engineer Battalion for the War Department’s Distinguished Unit Citation (now called the Presidential Unit Citation) for its critical defense of the Ardennes region against the German assault from December 16-18, 1944. The request was denied in 1946, much to the amazement of many of the officers who fought in the area and were familiar with the results the units had achieved, including General Anthony McAuliffe of the 101st Airborne.

There have been several other attempts since 1946 to have the U.S. Army reconsider its decision; however, each attempt has failed.

Because of the mass destruction of unit reports before their capture, there is no official list of the names of the men who fought in Hosingen, Luxembourg, from December 16-18, 1944. If you know of someone who fought there, please contact the author, Alice M. Flynn at www.HeroesofHosingen.com so that their contributions may be properly documented and recognized.

Alice M. Flynn is the author of the book The Heroes of Hosingen: Their Untold Story, available through Amazon.com.