By Phil Zimmer

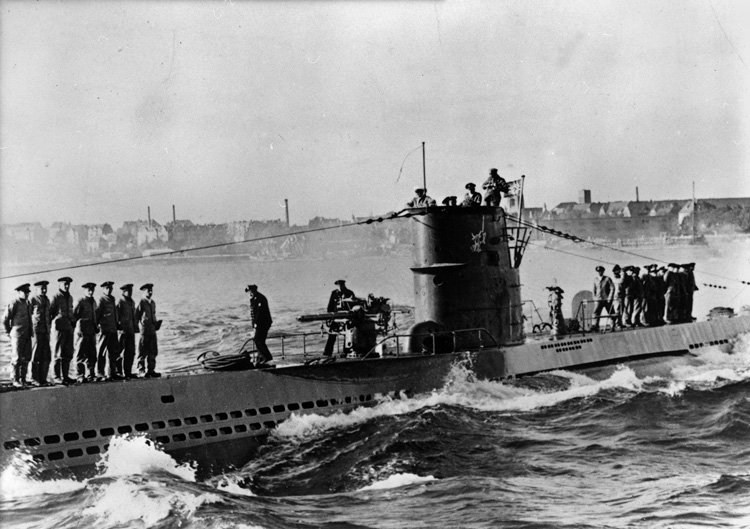

Late on the night of Friday, October 13, 1939, Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien surfaced his 218-foot-long submarine, U-47, and guided it through the protected, shallow, narrow channel at Kirk Sound. As the sub edged forward with electric motors turning in the treacherous currents, it moved ever closer toward where Prien believed the jewels of the Royal Navy lay in the broad anchorage.

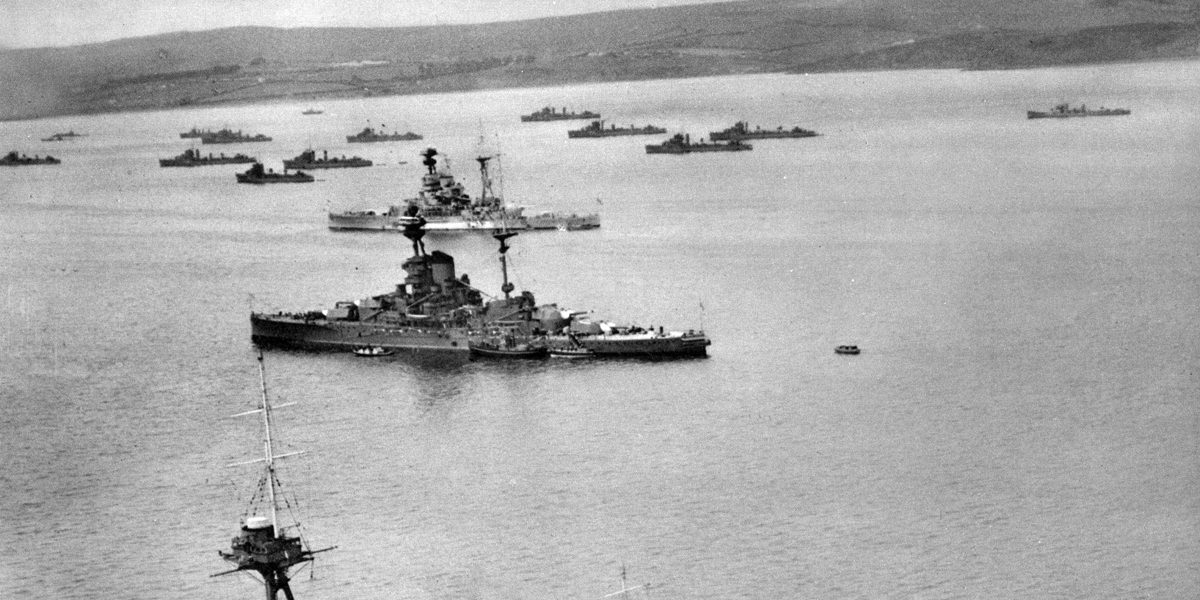

Prien’s strike against the British Royal Navy at its home in Scapa Flow off the north coast of Scotland, was nothing if not audacious, “the boldest of bold moves.” Nonetheless, before the sun rose on Saturday, October 14, U-47 had sunk the mighty battleship HMS Royal Oak and quickly escaped, leaving the ship abandoned upside down in 100 feet of water, with 833 crew members dead or missing.

Throughout its time of service, U-47 sank 30 other ships totaling some 162,769 gross registered tons and damaged eight more in its 10 war patrols before the sub itself disappeared in the North Atlantic in March 1941. Prien’s attack on the Royal Oak, though, was by far the most spectacular, and it stunned the British military and the public. They were just recovering from the shock of a German submarine attack a month earlier that had sunk the HMS Courageous, a converted aircraft carrier, off southwest England with a loss of 519 men and 48 badly needed Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes.

Serious questions were immediately raised by the sinking of the 30,450-ton Royal Oak in the protected harbor. How did U-47 manage to penetrate the Royal Navy’s supposedly well-defended home anchorage that spanned some 125 square miles? Did Prien and his cohorts have assistance from onshore? What about the car headlights that were seen near the shore, and what about the mysterious Swiss watchmaker of Kirkwall who reportedly disappeared after the sinking? Four of the sub’s torpedoes hit home, but what happened to the three others that either missed the target or failed to explode?

And why did U-47’s crew so quickly slink from the anchorage if they knew additional tempting targets remained untouched and so close at hand? Prien had, after all, believed he had spotted the prized battlecruiser HMS Repulse anchored just behind the Royal Oak. Equally important, why did Prien’s war diary differ so significantly from the reports that emanated from Berlin?

While the plan itself was hatched in Dönitz’s headquarters, the concept dated back to World War I. During that war, the Imperial German Navy attempted—with limited success—to penetrate the defenses blocking entrance to the deep, natural anchorage at Scapa Flow. In one incident, the submarine U-18 followed a steamer into the protected anchorage on November 23, 1914. Discovering it to be empty, the sub tried to escape, but was forced to surrender after suffering damage by being rammed twice by a trawler. The British further strengthened the anchorage’s defenses, and on October 28, 1918, UB-116 was lost with all aboard when an underwater magnetic detector alerted the defenders, who manually detonated the minefield that had been put in place.

Dönitz, who had served as a submariner in World War I, viewed the developing World War II plan as more than a way to weaken an exceptionally strong seagoing opponent. He and his superiors also undoubtedly saw it as a way to “even the score” for the loss just two decades earlier when 66 ships of the German Imperial Navy were scuttled at that very anchorage some seven months after the armistice had been signed. Scapa Flow remained a nagging reminder of the detested Versailles Treaty that had inflicted hefty reparations and the humiliation of defeat upon Germany after World War I.

This time around, the Germans held several advantages. Submarines were now faster and more maneuverable than their predecessors and could run deeper and stay submerged longer. German aircraft had progressed to the point where overflights of the anchorage were possible. Now German military leaders could obtain near real-time assessments of the size, numbers, and locations of the ships positioned there.

All in all, thorough research, preparation, and the selection of a bold and experienced submariner made a critical difference in U-47’s ability to evade and overcome the defenses at Scapa Flow.

Ironically, though, some contend it was the meticulous German preparations themselves that may have robbed Prien of even greater success. Two purported 11th-hour overflights by German reconnaissance planes—including one reportedly on Thursday afternoon—may have prompted much of the British Home Fleet to evacuate Scapa Flow by the morning of Friday, October 13. That “left the anchorage as empty as a ballroom after the band had gone home,” as one observer put it.

But the records are not clear on what precisely caused a large number of British ships to leave the anchorage just a day or two prior to the attacks, and the role of a German overflight on October 12 that supposedly showed a gaggle of more than 60 ships anchored there.

By far, the greatest cause for the departures, and one the Germans were hesitant to publicly admit, was a rather substantial German naval maneuver nearly a week earlier off the southern coast of Norway. It was designed to lure British capital ships to within reach of 139 Luftwaffe bombers and four Type IIB U-boats that lay in wait. The plan was also designed to draw attention away from the Graf Spee and the Deutschland, two German pocket battleships then operating in the Atlantic.

The exercise, planned by German Admiral Alfred Saalwachter, did successfully lure many British Home Fleet ships to the waters off Norway, including the carrier Furious, the battleships Nelson and Rodney, the battlecruisers Hood and Repulse, three light cruisers, and 13 destroyers. The German effort proved fruitless, and the U-boats returned to port, while most of the British Home Fleet was ordered to disperse rather than return to Scapa Flow.

The point remains that Prien believed he had entered a target-rich environment that included a tempting concentration of more than 60 ships, including such prizes as the battlecruiser Repulse and destroyers Fame and Foresight, all of which had departed along with scores of additional vessels well before U-47 neared the objective.

The earlier reconnaissance photos had revealed a 200-foot-wide northern passageway through Kirk Sound, between the sunken block ships Seriano and Numidian. It would be a dangerous but opportune entry point through which U-47, a Type VIIB U-boat with a draft of 15.5 feet, could travel on the surface through a 24-foot deep channel at high water that was laced with treacherous and constantly changing currents.

At that early stage of World War II, Kirk Sound also lacked boom defense nets, ASDIC (an underwater sound system to detect U-boats), minefields, patrol vessels, or even lookouts. Consequently, that channel to the anchorage was largely unguarded save for the existing four block vessels, their anchor chains, and the tricky currents.

The planners had employed U-14, a smaller Type IIB U-boat, to further scout the anchorage from September 13-29 to obtain additional details on tides, lights, and patrol boats. Based on those findings and additional research, Dönitz believed a U-boat could almost be swept through Kirk Sound without applying any power whatsoever because of the strong tidal currents prevalent at certain hours. Upon reflection, he felt it would be best to enter surfaced at slack tide using a submarine’s quieter electric motors rather than its diesel engines to power around the block ships. The dangers still would be substantial because the U-boat would not be able to submerge if spotted, and the jagged rusting block ships could easily rupture the submarine’s external dive tanks or even the hull itself.

Prien did manage to penetrate the anchorage, but not without incident. He planned to pass some 50 feet south of a block ship, but an unexpected current moved the Germans toward another block vessel. When the drift occurred, they spotted a cable from the second vessel extending northward into their planned path. A scraping sound was heard as the submarine’s port stern scraped against the cable. Prien ordered the port motor stopped, the starboard motor to slow ahead, and the rudders hard to port just as the submarine’s bottom clipped the floor of Kirk Sound. U-47 continued to move forward with a bit of a lurch as it managed to come free of the cable.

With a couple of additional quick turns to avoid becoming grounded in the shallow sound, Prien continued on the surface past the hamlet of St. Mary’s, located only some 850 yards away, where the Germans could see a dance in full swing in the village.

At that point, a vehicle’s headlights appeared to the crew of U-47 and later gave rise to questions of whether the Germans had been seen or even had inadvertent directional assistance on shore that night in the form of car headlights. Because of British wartime regulations, vehicles were allowed only one headlight with a slotted cover that permitted only a small amount of light to be cast ahead of the vehicle. Subsequent inquiries over the years determined that the vehicle was operated by taxi driver Bobby Tullock, who drove two couples from Kirkwall to the dance at St. Mary’s. After dropping them off, he did stop briefly along the waterway to tend to his headlight.

Confusing the issue is Prien’s occasionally inconsistent wartime diary, which states that a vehicle was spotted after the attack on the Royal Oak. The car reportedly stopped opposite the surfaced U-47 and then turned around and quickly sped off. A number of analysts, including this writer, believe that Prien may have inserted that comment as a way to help explain his decision to quickly depart the harbor rather than remaining a bit longer to prowl for additional enemy ships.

It is possible to conclude that Prien did not receive assistance from the driver of the vehicle, who may in fact have been cab driver Tullock. But then, what about the “Little Watchmaker of Kirkwall?” Articles in a 1942 issue of the Saturday Evening Post and a December 1947 issue of Der Kurier, a Berlin newspaper, talked about the wartime activities of Alfred Wehring, a German national and alleged intelligence operative who had been sent to Switzerland to learn watchmaking. He obtained the necessary papers in 1927 and traveled to Kirkwall in the Orkneys, where he opened a watchmaking and jewelry repair shop under the name of Alfred Ortel, a name strikingly similar to the Albert Hotel in Kirkwall. He reportedly learned of the defensive weaknesses at Kirk Sound and sent a shortwave report to his superiors. In one rather far-fetched version of the story, he personally piloted U-47 through the dangerous sound and even returned to Germany aboard the submarine.

While the tale of Alfred Ortel might form the foundation for a decent but somewhat imaginative spy novel, the story has no basis in fact, according to those who have thoroughly investigated the tale.

Another controversy revolved around the three torpedoes that either missed the Royal Oak or failed to explode on impact. The Germans were having difficulties early in the war with their torpedoes, caused, it was later discovered, by an overly complex impact pistol that did not work well at an impact angle of less than 20 degrees. The Germans also had difficulties with keeping the torpedoes at a proper depth and with properly heating and charging the torpedoes’ batteries.

One of three missing torpedoes was found at Scapa Flow and raised to the surface in September 2002. The other two may have gone astray or possibly struck the Royal Oak and failed to explode. Those eventually may be located elsewhere on the floor of the anchorage, possibly even beneath the 620-foot-long sunken ship.

Subsequent British inquiries also looked at why the Royal Oak’s antitorpedo blisters, added to the sides of the vessel in the interwar years, failed to protect it. It was found that the blisters were designed in 1924 to withstand torpedoes with 450- to 500-pound warheads. The newer German G7e torpedoes carried 617 pounds of Hexanite, more than enough to breach the starboard blister and create enough damage to sink the Royal Oak within 15 minutes.

Prien had expended seven of the 12 torpedoes that his Type VIIB craft could store internally, and after his success, he decided to scamper from the confines of the harbor, slipping through the southern portion of Kirk Sound. He might have created further damage, but he knew he had accomplished his major goal of striking a significant blow at the very heart of the Royal Navy.

There are a number of inaccuracies and embellishments in Prien’s war diary that distract somewhat from his accomplishments and his subsequent nickname, “The Bull of Scapa Flow.” He described, for example, the harbor coming alive with activity after the explosions and the sounds of depth charges, while British reports run to the contrary. But there is no question that following the bold attack, he took a balanced and sound approach to preserving his vessel and men for future attacks against a powerful enemy.

The daring attack was praised in every corner of Hitler’s Third Reich. Prien and the crew were enthusiastically received when they returned to port in Wilhelmshaven. Raeder personally awarded the entire crew the Iron Cross Second Class, while Prien and two others received the even more prestigious Iron Cross First Class. Then the entire crew was flown to Berlin, chauffeured through the streets of the Nazi capital lined by cheering fans, and Prien was personally presented the Knight’s Cross by the Führer.

While he and his officers could have lingered longer at Scapa Flow to inflict further damage, and despite their misidentification of the Repulse being in the harbor adjacent to the Royal Oak, there is no doubt that the overall operation was a bold, spectacular success in military terms. U-47 managed to slip into the harbor undetected, sink the only capital ship in the anchorage, and depart unscathed to fight another day.

It was, as none other than Winston Churchill ruefully admitted, a “remarkable exploit of professional skill and daring.”

Phil Zimmer is a U.S. Army veteran and a former newspaper reporter. He has written on a number of World War II topics.