By Christopher Miskimon

In the predawn hours of April 24, 1945, SS-Brigadeführer Gustav Krukenberg received orders from Army Group Vistula defending Berlin to immediately lead the remnants of the 57th Battalion of the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne from its staging area at the SS training camp at Neustrelitz to the German capital.

Krukenberg’s orders called for him to report to the Reich Chancellery for further orders upon arrival in the besieged city. He then awoke Hauptsturmführer Henri Fenet, commander of Sturmbataillon Charlemagne, as the 57th Battalion also was known. Krukenberg instructed Fenet to assemble his men so that Krukenberg could address them. Attired in a gray leather greatcoat, Krukenberg asked for volunteers to go with him to fight the Red Army in Berlin. This would be their last battle.

Although most of the troops wanted to go, just 90 were chosen because there were only a handful of vehicles available to transport them. They set out at 8:30 amin two half-tracks and three heavy trucks. Krukenberg led the convoy along back roads through pine forests where possible to avoid being strafed by marauding Soviet fighters.

Because Soviet forces were blocking the northern entrances into Berlin, the convoy had to take a circuitous route into the bombed-out city. Entering the city from the west, they passed columns of retreating German troops. Some of the retreating Germans taunted them by shouting that they were going the wrong way. Others tapped the sides of their heads to convey that they believed the Charlemagne soldiers were crazy to be heading into battle rather than away from it. The convoy had to navigate its way around barricades and through rubble-choked streets to reach its destination. At 10 pmthe convoy stopped for the night at the Olympiastadion on the east bank of the Havel River in the western section of the city.

While the Charlemagne troops rummaged for refreshments of any sort in a Luftwaffe supply depot, Krukenberg made his way to the Reich Chancellery. He received orders from General of Artillery Helmuth Weidling to take command of Defense Sector C in southeast Berlin. To defend the sector, Krukenberg would have the volunteers of Sturmbataillon Charlemagne, the remnants of two regiments of the 11th SS Panzergrenadier Nordland Division, and whatever other soldiers Weidling’s staff could scrape together.

The Waffen-SS soldiers of the Charlemagne and Nordland Divisions were willing to fight to the death with other troops of the so-called Berlin Garrison, not because they were ardent Nazis, but rather because they were vehemently anti-Bolshevist. Their last stand in the streets of Berlin was made in the face of insurmountable odds against which any sort of victory was utterly impossible.

The foreign Waffen-SS units of Nazi Germany were an outgrowth of the native German Waffen-SS. The Waffen-SS organization has attained near-mythic status in the annals of World War II history. The organization began as part of the Nazi Party’s private security apparatus known as the Schutzstaffel. The soldiers in the unit furnished security at Nazi Party functions.

The SS expanded in the wake of Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor of Germany in January 1933. Shortly afterward, the organization comprised three distinct branches. The first branch was the Allgemeine, or General SS, which oversaw administrative and policing functions. The second branch was SS-Totenkopfverbande, the Death’s Head Units, which operated concentration and extermination camps.

The third branch was the Waffen-SS, meaning Armed SS. This part began as a small armed force loyal only to Hitler. The Waffen-SS later expanded into a major military organization. Although the lines were not always clear between the three branches, it was the Waffen-SS that was equipped for war and eventually deployed for battle.

A dichotomy exists in the popular conception of the Waffen-SS. On one side, they are viewed as criminals who killed prisoners, massacred civilians, and showed little mercy. Indeed, SS troops were guilty of all these behaviors. On the other side, they are seen as modern knights and regarded as patriots who fought for their country against the scourge of Bolshevism. In this sympathetic portrait, they are painted as superbly trained and equipped soldiers who inflicted heavy casualties on their battlefield opponents.

The latter view of the Waffen-SS is flawed for two reasons. First, it endorses Nazi propaganda, which presented SS troops as elite for political and recruiting purposes. Second, most existing first-hand accounts of the Waffen-SS in action were written by SS soldiers. Like many accounts penned by soldiers, there is always the temptation to embellish their achievements. As defeated soldiers serving a criminal regime, their memoirs often seek to justify their service on patriotic grounds or to deny that any atrocious conduct occurred. Many SS veterans worked tirelessly after the war to repair the Waffen-SS’s tarnished reputation. Whatever the individual member’s actions or conduct, the Waffen-SS served a government guilty of extensive and pervasive criminal behavior and, therefore, is forever tainted by that association.

Yet SS lore also omits the fact that many of the men who served in the Waffen-SS were not German citizens. By war’s end, there were numerically more non-Germans serving in the Waffen-SS than natural-born Germans. The Waffen-SS leadership recruited and fielded entire divisions along ethnic lines. In the latter part of World War II, all regular SS divisions had some foreign soldiers assigned to them. Of the 38 Waffen-SS divisions, 21 were raised with non-Germans as their primary personnel.

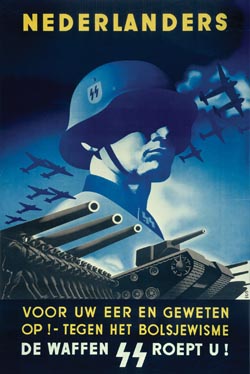

The entry of foreign citizens into the Waffen-SS began early in the war. The recruitment of volunteers for the Waffen-SS outside the borders of Nazi Germany was part of SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler’s dream of a pan-European army for the Third Reich. He conceived as early as 1938 the concept of recruiting men of sufficiently Germanic heritage and blood for the Waffen-SS.

The success of the Wehrmacht in the first years of the war placed this dream within reach. As the Nazis conquered and occupied Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, and France in 1940, millions of Western Europeans came under their dominion. These were exactly the captive populations Himmler wanted for recruiting his European Waffen-SS.

Himmler assigned SS Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger to assist in this effort. Berger, a decorated World War I veteran, joined the brown-shirted Nazi Party paramilitary organization known as the Sturmabteilung (SA) in 1930. An arrogant and belligerent individual, Berger was roundly disliked by the majority of the SA membership. He transferred to the SS in 1936 and subsequently became its chief of recruitment. An advocate for the addition of foreign volunteers, he played an instrumental role in the expansion of the SS.

After the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939, non-German membership in the Waffen-SS grew in importance. The Waffen-SS and the Wehrmacht competed for recruits. The Wehrmacht had an edge in the recruitment race because it could restrict the number of volunteers who could enter the SS.

Berger realized it was going to be difficult to bring in enough replacements to keep the existing SS units at sufficient strength, much less create new formations. At that time, the SS did not have a reserve system like the Wehrmacht’s that funneled new recruits into combat divisions.

The Wehrmacht, though, did not control two groups of potential recruits. One group was the Volksdeutsche. These were individuals of German descent who had settled throughout Europe in the preceding centuries. The Nazis regarded the Volksdeutsche as ethnically German. Their language and culture had German origins, but they were not German citizens.

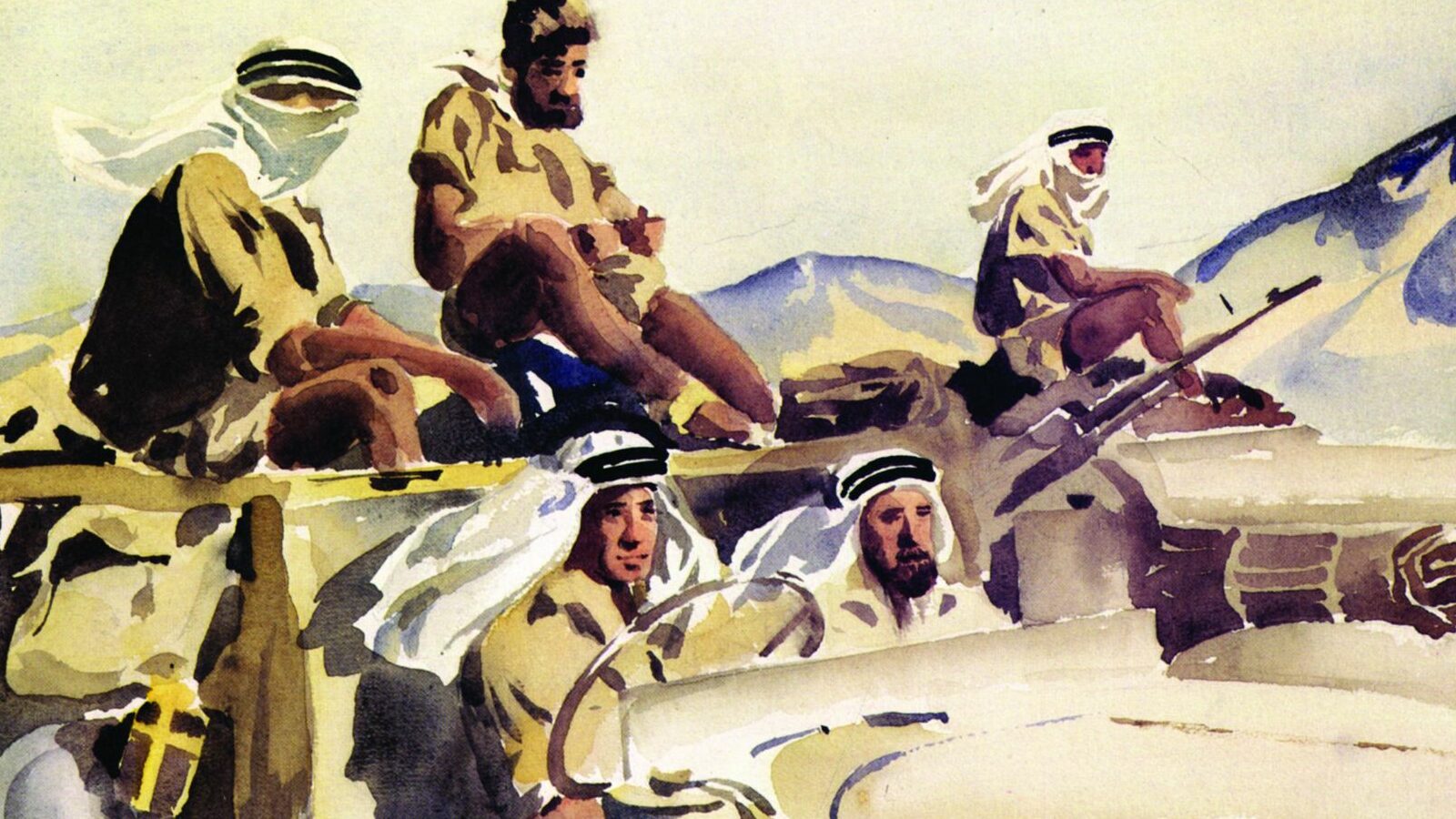

The other group was composed of individuals who looked Germanic. This group included those of Nordic descent who were Teutonic enough to serve in the military forces of Nazi Germany. This group included Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, Dutch, Belgian Flemings, and Swiss from the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland.

Once the Nazis had occupied these countries, it became easier to recruit within their borders. This put Himmler’s dream of an Aryan European army within reach. Although Hitler considered the Third Reich as an entirely German and Austrian endeavor, Himmler thought in terms of ethnicities rather than strict national borders.

Berger moved quickly. The first Waffen-SS recruiting offices in the occupied countries were established in June 1940. Berger had made contact before the war with various right-wing groups throughout Western Europe; this sped the recruiting process. The Waffen-SS soon had offices in Oslo, Copenhagen, Antwerp, and The Hague. Since Sweden and Switzerland were officially neutral, German embassies in those nations worked quietly with right-wing groups to gather recruits.

Berger’s optimism for the rapid creation of a multinational Waffen-SS was soon dashed. Few men appeared at the recruiting stations. Those who did show up were often treated as collaborators by their countrymen. They had different motivations for volunteering. Some were dedicated Nazi sympathizers or simply Germanophiles. They wanted to join the seemingly unstoppable Nazi juggernaut. Others enlisted for more mundane reasons, such as to escape poverty. For the impoverished, the Waffen-SS offered the promise of warm barracks and hot meals.

It was a myth that all SS men were volunteers. Recruiters deliberately misled some enlistees regarding what they would be doing. For example, a group of Danish men were told that they were going to Germany to participate in political and athletic training. Similarly, 500 Flemish factory workers employed by the Germans in northern France volunteered for work in Poland under the pretense of higher pay. These men discovered upon arrival that they had been whisked into the Waffen-SS.

Waffen-SS recruiters were instructed to turn a blind eye to volunteers who were awaiting criminal prosecution in their countries or who were known juvenile delinquents. Berger believed that criminals made outstanding soldiers—if one knew how to handle them. He said that he knew some of the recruits would be less than ideal and would join for other than ideological reasons. He dismissed these concerns on the grounds that these were age-old recruiting problems for all nations.

Recruitment increased in many areas in the wake of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Men who were not committed Nazis, but instead staunch anticommunists, enlisted in the hope of eradicating the threat that Bolshevism posed to Western Europe.

“I joined the Waffen-SS to help the Finns,” said Asbjorn Narmo, a member of the Norwegian Waffen-SS. “I wanted to go earlier to help them fight the Russians, but they wouldn’t let me. So when the Germans said they would send volunteers there, I enlisted.”

Narmo joined a specialized company of ski troops and fought alongside the Finns in the so-called Continuation War, a portion of the fighting on the vast Eastern Front. The Continuation War had begun just 15 months after the conclusion of the Winter War in which the Soviets had tried to annex part of Finland’s eastern frontier.

The SS leadership formed these early volunteers into several new regiments that grouped recruits of similar national heritage into the same unit. The first two regiments were named Westland and the Nordland. The Waffen-SS Regiment Westland was composed of Netherlanders and Belgian Flemings. The Nordland Regiment was composed of recruits from Norway, Denmark, and Sweden.

None of these regiments reached its projected manpower goals, though. The SS leadership added Germans to the regiments to bring them to full strength. These units were combined with SS Infantry Regiment Germania and designated the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking. Yet despite their best efforts, less than 10 percent of the recruits in the unit were foreign nationals when it took part in Operation Barbarossa.

The Nazis also began recruiting new nation-based SS units, in an effort to boost the numbers of volunteers through a sense of national identity. SS leadership generally designated these units as either “legion” or “free corps” to reflect that their members were volunteers. Most of these units numbered 1,000 volunteers, which was slightly more than made up a standard Wehrmacht infantry battalion. The small units could hardly be expected to have a real influence on a theater of war as vast as the Eastern Front, given that 3.8 million Axis troops participated in Operation Barbarossa.

The Germans used these national units later in the war to form the nucleus of new SS divisions as the need for new combat formations became desperate. A new division was usually brought up to strength with whatever personnel were available. Under such conditions, any semblance of national or cultural identity was superficial at best.

The training of the new units became another point of contention. Most of their instruction came from German Waffen-SS cadre. The recruits complained of poor treatment. Their complaints were not about the rigorous training, but rather about the abuse and dismissive attitude they encountered. A number of high-ranking Waffen-SS officers stepped in to stop these abuses, but they were never completely successful.

Most of the newly established Waffen-SS foreign units did not fare well on the Eastern Front. The SS leadership attributed their poor performance to inferior leadership. But the real reason was a lack of proper training and equipment. The Wehrmacht generals looked with disdain upon the Waffen-SS. They viewed them not as elite soldiers, but instead as poorly trained fanatics who achieved their objectives at a high cost in casualties. Often they did not receive the same standard of training as Wehrmacht units.

Despite the Waffen-SS having more than its share of the training and other problems common to any military force, it saw its share of fighting. Ivar Corneliussen, a Danish volunteer in the Westland Regiment, recalled the hard fighting in the Ukraine. “I saw a Cossack attack with my own eyes, all of them on horseback and waving their sabres,” he said. “They charged towards us, it was madness, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. We mowed them down, dozens and dozens of them. It was just slaughter, the machine guns shredded them.” He said that when it was all over, the Danes went out onto the steppe and shot the wounded horses to put them out of their misery.

When Germany turned its attention to the East, it opened up entirely new recruiting possibilities for the Waffen-SS, for there were untapped areas of Volksdeutsche scattered throughout Eastern Europe. Himmler and Berger recruited them and formed them into new units. They recruited heavily among the ethnic Germans in Romania and Hungary. Since these countries were key Axis allies, however, they naturally recruited their citizens to serve in their own armies. To circumvent this, Waffen-SS recruiters went so far as to hide Romanian recruits among German units. Thus, when the German unit moved out of the country, the recruits went with it.

Occupied countries, as opposed to allied countries, were different propositions altogether. In the case of Yugoslavia, the Nazis took advantage of the country’s long-standing ethnic and religious tensions to recruit as many troops as possible.

Himmler ardently pushed for the creation of an SS division in Yugoslavia to combat partisans. The Serbs were formed into an SS-led militia force that became the nucleus of the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen. But like most foreign-based Waffen SS divisions, there were not enough recruits to fill its ranks.

Himmler, who feared that Hitler would withdraw his support for the unit if it could not be fully manned, ordered his subordinates to use coercion to complete the task. His henchmen began covertly conscripting men. This occurred among the Volksdeutsche throughout the rest of the war, thus ending the pretense of the Waffen-SS as an all-volunteer organization.

New recruits also came from German-occupied territories in the Soviet Union. Many Latvians, Estonians, and Ukrainians, themselves unwilling subjects of Stalin’s empire, joined the Waffen-SS out of a desire to prevent the communists from returning to their countries. Even the German Waffen-SS leadership realized these men had no real love for either Germany or for Nazi doctrine, but instead hoped to garner privileges for their homelands in postwar Europe should Germany win. Although these units were often used against partisans, they also saw action on the front lines.

Oskars Perro, a Latvian volunteer assigned to a special-employment unit of the Waffen-SS, found himself in the Novgorod town of Kholm in January 1942. He was part of a 15-man detachment sent to Kholm for antipartisan work. Before this assignment, Perro’s unit was attached to Einsatzgruppe A, one of the death squads that conducted mass executions of Jews and other groups in German-occupied Europe.

In the predawn hours of January 18, a Soviet partisan force attacked the town, which was defended by a mixed group of German rear-echelon personnel. Perro and his fellow SS men were sleeping on beds of straw in a school building when the sharp crack of a rifle shot woke them. They heard shouting outside and quickly took up arms. Each man took his position at a window. Perro heard machine guns chattering in the distance and the muffled crump of grenades exploding in the deep snow. After the attack, Perro’s squad walked to the center of town. They found before them the bodies of slain partisans. There were also several dead German sentries with knife wounds in their backs, indicating that partisans had succeeded in infiltrating German lines to carry out retaliatory attacks.

The 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division remained in Yugoslavia, where it fought Tito’s partisans from late 1942 on. The unit, which was equipped with obsolete or captured weapons and commanded by German officers and NCOs, engaged in operations marked by brutality. They gave no quarter, and neither did their opponents. The division was not remembered for its combat prowess, but instead for the atrocities it committed.

The Prinz Eugen Division performed badly in its first confrontations with the Red Army in mid-1944. Although a few of its soldiers received decorations for valor, these were generally ethnic Germans rather than non-German troops. Once the tide of war had turned in favor of the Russians, the Balkan soldiers began deserting in droves.

Two other Waffen SS divisions raised in the Balkans became infamous as a result of their atrocities. The 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS (Handschar) was created in the spring of 1943. It was composed of Bosnian Muslims, a seemingly odd choice for the race-sensitive Nazis. It was a deliberate choice, though. Most of the communist partisans came from Christian areas. The Nazis deliberately exploited the simmering racial hatreds of the region. This was perhaps the only division with an excess of recruits, because the local Muslims wanted an opportunity to strike at their lifelong enemies. Members of the unit wore a patch with a scimitar over a swastika on their collar instead of the typical SS lightning bolt runes. They also wore the fez as their headgear. They donned a gray fez for service in the field, and they wore a red one for their dress uniform. An SS Death’s Head insignia adorned the fez.

The Handschar was trained in France, where some of the soldiers mutinied and killed their German officers. The Germans executed some of the ringleaders in retaliation and sent others to concentration camps. The Handschar went into action against partisans in early 1944 and quickly gained a reputation for brutality. By the end of the year, the division had suffered thousands of desertions and was soon disbanded. The SS leadership sent the remaining Bosnians to labor units. The reliable German elements of the division were transferred to other Waffen-SS units.

The other unit formed in the region was the 24th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS (Karstjager). The Karstjager was formed primarily of Volksdeutsche from Yugoslavia, Hungary, Romania, and the Ukraine. It started as a battalion and was later expanded to a division in the summer of 1944, although in reality it was never larger than a brigade.

The Karstjager Division first operated against partisans in northern Italy and in Dalmatia; after that, it was sent to North Africa, where it contended with the British 8th Army. While it fought hard against the British, the Karstjager never became infamous for the types of atrocities committed by the other Balkan-raised units; unlike those formations, it retained a reputation for reliability and esprit de corps. What was left of the Karstjager Division surrendered to the British in May 1945.

While the Waffen-SS divisions in the Balkans were fighting partisans, other foreign-born SS troops were fighting and dying on the Eastern Front. As with the enlistment of Bosnian Muslims, the SS leadership relaxed other racial rules. As the war progressed, Waffen-SS divisions became for the most part mixed units.

When the soldiers of the SS Nordland Division were sent to the Balkans to refit, they found no respite. Instead, they found themselves heavily engaged against Tito’s partisans, with brutality against the enemy becoming a routine occurrence. By 1945 most German units, whether Wehrmacht or SS, were fighting not only to hold off the Soviets a little longer but also for simple survival.

In mid-March 1945 the Germans formed elements of various SS units into a battle group to defend the Hungarian village of Sored from a Soviet attack. Hans Geissendorf, an officer of the 3rd SS Panzer Division Totenkopf’s Sturmgeschutz battalion, witnessed the futile struggle of his SS soldiers. Having run out of ammunition for their various weapons, the SS soldiers resorted to using their knives and entrenching tools to defend themselves.

Russians emerged from foxholes 50 yards away. They offered the Germans an opportunity to surrender. When the Germans declined the offer, the Russians attacked in force. Waves of communist soldiers advanced, supported by Soviet heavy tanks. A reconstituted battalion of the Nordland Division, which subsequently had been attached to the Wiking Division, accompanied the assault gun battalion.

“The Danes of Panzergrenadier Regiment 24 Danmark fought heroically,” said Geissendorf. “I was with our Sturmgeschutz at the outskirts of the town with an infantry squad. In the midst of this inferno, a messenger came and yelled out that it was over and we should attempt to escape towards the West.”

The reason for this was that other assault guns had become mired in the sodden fields west of the town. The assault guns that Geissendorf and his squad accompanied soon became stuck in the soggy terrain, as well. “I blew up our assault gun with a panzerfaust,” Geissendorf said. “We ran for our lives [with] artillery rounds always exploding just in front of us. I saw several officers from both our division and SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 24 Danmark shoot themselves because they could go no further.”

As the Soviets encircled German units in the nearby village of Stuhlweissenburg, the morale of the Wiking Division started to break. Oberführer Karl Ullrich decided to save his division from destruction. He ordered his troops to break out on March 22. This flew in the face of Hitler’s long-standing policy that German forces were not to give ground.

Another German SS division, the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen, fought to keep an escape corridor open for the Wiking troops. Hitler flew into a rage upon learning of the retreat of the Wehrmacht and SS units. Five days later he issued orders that the men of the Hohenstaufen Division were to remove their distinctive armbands that indicated they belonged to an elite division.

The death knell of Nazi Germany came in Berlin. Trapped between advancing Allied armies from the East and West, many Waffen SS units were ordered to Berlin to take part in the what would be the last battle. At this point, virtually all German units were shadows of their former selves, depleted of men and short of weapons, equipment, and fuel. Divisions were by then reduced to battalion strength.

Still, the SS fought on. The bonds shared by its soldiers as the result of having fought side-by-side for years held many of them together. This was true for ethnic Germans, as well as for foreign-born SS troops. They were willing to fight to the finish, in large part, because they had nowhere to go. They could not return to their homelands, and capture by the Soviets meant almost certain death. “Even in the last hopeless days there was no question of laying down our weapons,” said one SS soldier.

Some of the Waffen SS men still felt there was a chance for victory even when the war had only weeks left, believing in the promise of wonder weapons. “We knew important things were going on, that sensational weapons would soon be put into action, and thanks to that, the war would take on a completely new character,” said Erik Wallin, a Swede in the Nordland Division. “We knew that even better things were coming.”

The Red Army forces fighting their way into Berlin found a special way to honor Hitler’s birthday, April 20, 1945. They celebrated the occasion by bombarding the center of Berlin with their long-range artillery.

Hitler flew into one of his last rages two days later when Steiner’s 11th SS Panzer Army, created in the final weeks of the war by Himmler, failed to carry out an attack order. Hitler’s outburst is believed to have occurred because the Waffen-SS, which he believed had never before failed him, finally gave out. Within the city, though, were a number of Waffen-SS units, including the remnants of the Nordland and Charlemagne Divisions. They were determined to fight to the very end.

The street fighting in Berlin followed the Soviet victory at Seelow Heights, fought from April 16 to April 19 on the west bank of the Oder River. The last large-scale battle between the Germans and Russians had pitted Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front against Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici’s Army Group Vistula.

The Soviets, who outnumbered the Germans 10 to one, fought their way through Heinrici’s layered defense and entered the city. At that point, Stalin also directed Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front, which was situated southeast of Berlin, to fight its way into the city. This produced a heated rivalry between Zhukov and Konev in which each sought to be the one regarded as the conqueror of Berlin.

The Russians relentlessly struck the Germans with a blend of massed artillery, armor, and infantry. Most of the Volkssturm scattered, but the Hitler Youth fought heroically in the last week of April, to the admiration of the foreign SS troops.

The foreign SS troops found the intensity of the Soviet artillery bombardment unnerving. SS Nordland soldier Erik Wallin and his comrades took position in an abandoned house, but they could not escape the ferocity of the Red Army’s heavy guns. “[The artillery] sang and thundered all around and the blast waves threw us, half conscious, to and fro between the walls,” wrote Wallin. “The defenders who were killed by collapsing walls, ceilings and iron girders numbered more than [those] who got a direct hit. It became unendurable to stay in this inferno. Whirling stone, scrap iron and bloody body parts made the air impossible to breathe, filled as it was with limestone dust and gunpowder gases.” Wallin and his fellow SS soldiers evaded encirclement by escaping through narrow passages and backstreets. All the while their losses mounted.

On April 25 Fenet’s soldiers joined forces with the remnants of SS Nordland Division’s Danmark and Norge Regiments, as well as some of the men of the division’s pioneer battalion. The Nordland troops, who were led by Sturmbannfuhrer Rudolf Ternedde, also possessed a few tanks and assault guns. They had continued to fight after the Battle of Seelow Heights even as other German units fled west in the hope of surrendering to the Americans at Charlottenburg rather than the deeply embittered Russian troops. The SS troops were augmented by a smattering of other Waffen-SS personnel, including Finns, Latvians, Spaniards, and Hungarians. In addition, their numbers included some fanatical Hitler Youth and poorly armed Volkssturm.

The combined force assembled near Tempelhof airport on the south side of the city. They managed to advance just over half a mile before Soviet resistance stopped them. Col. Gen. Vasily Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army spearheaded the Russian assault. The Russian infantry was supported by tanks from Col. Gen. Mikhail Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army. By noon Fenet’s command post was under heavy enemy machine-gun fire. The foreign Waffen-SS soldiers launched their own counterattack. They initially forced back the Russians, but reinforcements arrived. They soon found their flanks assailed by the enemy as the Soviet soldiers sought desperately to encircle and destroy the assembled force.

The foreign Waffen-SS soldiers withdrew and set up a defensive position at nightfall. The Nordland panzer troops positioned some of their assault guns behind barricades made of paving stones. When more Russian tanks arrived, the assault guns opened fire. They knocked out several enemy tanks before running out of ammunition. The Nordland panzers withdrew. Without their armored support, Fenet’s men fell back. The Frenchmen bedded down for the night in a beer hall near the Anhalter train station.

The fighting continued the next day with the foreign SS troops heavily engaged against Chuikov’s spearhead. “Our men advanced as if on maneuvers, leapt from door to door and fell upon the Red snipers hidden in the upper storey,” wrote one SS-Charlemagne soldier. “The tanks behind them spewed fire and flames and barely gave the enemy infantry the opportunity to fire effectively. Our attack gained ground, but then we suffered a severe blow.”

The Hitler Youth fought heroically, attacking Soviet tanks at close quarters with handheld panzerfausts. As for his troops, Fenet claimed that they destroyed 62 Soviet tanks in the desperate fighting.

The Soviets made heavy use of tanks in the Berlin fighting and suffered heavy losses in the close-quarters fighting to panzerfausts and other antitank weapons. “There was no limit to their tank forces,” recalled Wallin. “The infantry we saw less and less…. We realized the forces ranged against us were exclusively tanks, assault guns and entire battalions of Stalin organ rockets. There wasn’t an infantry soldier among them.”

Fenet said the Soviet infantry also used flamethrowers to clear out German pockets of resistance. “There was fighting everywhere,” he recalled, “in the backyards behind the houses, on the roofs, with assault rifles, with hand grenades and with bayonets. The smoke and dust almost choked and blinded us. We could only see for half a meter. Our tank hunters were constantly on the alert. Wilhelm Street was littered with burning tanks, their ammunition exploding and their fuel tanks blowing up in flames.”

A small number of Charlemagne troops had barricaded themselves in a basement of the former Gestapo headquarters. About 100 military policemen fought alongside them. Fenet, who was wounded in the foot, continued to lead them. Generalmajor Wilhelm Mohnke, a former commander of the German SS Division Leibstandarte, presented him with a Knight’s Cross.

Many of the Charlemagne troops were eager to earn a Knight’s Cross, so Fenet passed out the few he had to deserving soldiers. The next morning the French hid in a building at the Air Ministry. At that point, all was quiet. A few cars flying white flags appeared. Russian troops accompanied by German officers exited the cars and implored the French SS men to surrender. A Luftwaffe major told Fenet the surrender document was signed and that his unit should capitulate.

The Frenchmen decided to try to break out. They moved through subway tunnels until reaching the Kaiserhof station. They could hear Russian troops in military vehicles on the streets above blowing their horns in celebration. The SS men eventually reached a bridge near the Potsdam train station and hid beneath it. Their plan was to resume their flight at night in the hope of reaching the formation commanded by General of Panzer Troops Walther Wenck

Wenck had directed his troops to fight solely for the purpose of keeping open an avenue of escape so that civilians and soldiers fleeing Berlin during this final battle might reach Allied lines. But before the French SS soldiers could leave the bridge, the Russians captured them. They were among the 130,000 German troops taken prisoner by the Russians in and around Berlin.

A few Waffen-SS foreign fighters did manage to escape Berlin, but the reprieve they attained was temporary. One Norwegian SS soldier was captured but escaped his drunken guard and made it to the British. Another hid in a cellar before making his way to the coast and boarding a boat to Denmark, where he was soon arrested.

SS Nordland soldiers Wallin and Hans-Gota Pehrsson managed to successfully escape from Berlin. Disguising themselves as Italian refugees, they made their way past two Soviet checkpoints and onto a ferry that took them across the Elbe River into British-controlled territory.

Most of the German soldiers who reached Allied lines were returned to their home countries, where they were arrested and put on trial. The Russians captured Fenet and returned him to France where he received 20 years at hard labor. He was later released after serving only half of his sentence.

The Russians and Cossacks who served in various SS formations were returned to the Soviet Union. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered the execution of many and the remainder he sent to the so-called Gulag Archipelago in Siberia.

Of the Soviet soldiers serving in the Waffen-SS, the Ukrainians of the Galician Division fared the best. The Red Cross, the Vatican, and the Polish Army all intervened on their behalf. Because of this, they were not returned to the Soviet Union. After a brief internment, they were allowed to emigrate to the United Kingdom and North America.

In Yugoslavia the results varied. Many SS men were poorly treated, but President Josip Broz Tito realized he would have to tread lightly in order to successfully unite the disparate ethnic groups within Yugoslavia’s borders. Those accused of specific crimes against Yugoslavians were put on trial, while amnesty was granted to the rest, including former SS men.

The effectiveness of these Waffen-SS divisions was mixed. Although some of them evolved into formidable fighting units, many never performed well and were often limited to fighting partisans. Yet whatever their record in combat, almost all Waffen-SS divisions were involved in various crimes, including the execution of prisoners of war, massacres of civilians, and various other misdeeds. Some foreign-born Waffen-SS fighters came from units that were involved in the deportation of Jews and others to the concentration camps. On the whole, the criminality of the Waffen-SS is beyond dispute and forever tied to the regime it served.

There’s no denying that the foreign Waffen-SS units were vital to the expansion of the Waffen-SS. Indeed, through the incorporation of foreign troops, the Waffen-SS managed to double in size every 12 months beginning in late 1942. The strength and effectiveness of the Waffen-SS in the second half of World War II would have been vastly reduced without the infusion of hundreds of thousands of foreign troops, many of whom served until the bitter end in Berlin.