By Eric Niderost

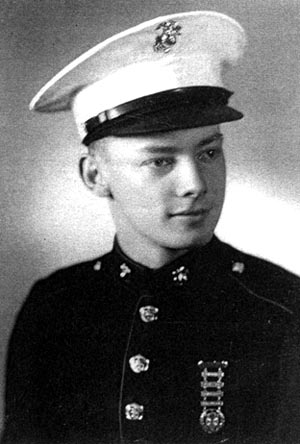

When Marine Private Donald Versaw arrived on the fortress island of Corregidor in the Philippines on December 28, 1941, three weeks after Pearl Harbor, he was impressed by how normal everything looked. Trolley cars rumbled through streets crowded with people going shopping or on their way to work. Barracks and other buildings were impressive structures, bordered by well-kept hedges and a kaleidoscope of brilliantly colored tropical flowers. Versaw’s 4th Marine Regiment had been sent to the island to bolster its vulnerable perimeter from land attack.

Versaw and the Marines were happy about the assignment. Corregidor was a legend in its own time, a place that was called the “Gibraltar of the East.” The appellation was no idle boast. There were 23 gun batteries on the island, with no less than 45 coastal guns and mortars. “I thought it was a break for us to be sent to Corregidor,” Versaw admits today. “I heard that it was armed to the teeth with big guns and was protected by a big minefield. It was known that one gun ashore is worth three or more afloat.”

With Japan and the United States already at war, Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma’s veteran 14th Army landed on December 22, 1941, at Lingayen Gulf on the main island of Luzon. The knowledge that war was literally approaching their fortress only added to Corregidor’s air of unreality.

The Marines soon occupied Middleside barracks, a concrete structure that looked so solid they believed the Army scuttlebutt that it was bomb proof. That first day on the island the 4th Marines were taken around to better acquaint themselves with their new home. “It was a paradise,” Versaw recalls. Topside was the highest point on the island, rising some 500 feet above the waters of Manila Bay. The young Marine gazed in awe at its “the huge parade ground” and impressive Topside barracks, three stories high and supposedly a mile long.

Versaw and his buddies learned that Middleside was a small plateau near the center of the tadpole-shaped island. To the east was Bottomside, where the barrio (town) of San Jose was located. Still farther east was Malinta Hill, where the Malinta Tunnel could be found. The tunnel housed a hospital and the headquarters of USAFFE (United States Army Forces, Far East). Corregidor ended in a curved, snaking tail, featuring an airfield (Kindley Field) and a Navy radio intercept station.

Though they didn’t know it at the time, Private Versaw and the other leathernecks were given a glimpse—a sadly fleeting glimpse—of how life had been on the island since World War I. Bristling with guns, it seemed impregnable, and garrison life was so comfortable even enlisted men considered duty there a plum assignment. But Corregidor’s golden age, like all golden ages, was not destined to last. Within 24 hours, the first Japanese bombs would fall and signal the beginning of a four-month ordeal that would earn the island a hard-won immortality.

In many respects Corregidor’s story begins in 1898, when the United States took over the Philippines from Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War. With the acquisition of the Philippines, the U.S. Navy now had access to Manila Bay, one of the finest natural harbors in Asia. An American naval station was established at Cavite where the Spanish once had had a similar base. Cavite became very important as a support and repair facility for the U.S. Asiatic Fleet.

There were other considerations as well. The great bay, some 30 miles across, is the doorstep to Manila, the political and administrative capital of the Philippines. The mouth of Manila Bay is about 12 miles wide and provides access to the South China Sea. The Bataan Peninsula is on one side of the bay entrance, while the other side is dominated by the looming Pico de Loro Hills of Cavite Province.

American planners in the early 1900s focused on a group of volcanic islands that spread across the entrance of Manila Bay like a rocky necklace. There was the solution to their problems: fortify these islands, convert them to fortresses, and any enemy ship attempting to enter the bay would have to run a gauntlet of interlocking shellfire.

Responding with alacrity, the U.S. government declared the Manila Bay islands military reservations on April 11, 1902. The Army Corps of Engineers made surveys, and the first of many batteries on Corregidor was begun in 1904. Work continued for more than a decade, and steady progress was made. By 1920 the various island fortifications were complete. They were state-of-the-art at the time, but would soon fall into obsolescence.

Corregidor, formally named Fort Mills, was the main post and headquarters for the harbor defenses of Manila Bay. The majority of Corregidor’s batteries featured 12-inch, breech-loading rifled artillery backed up by 12-inch mortars, the latter providing plunging fire that ideally could pierce a warship’s relatively thin deck armor.

Battery Cheney, located on Corregidor’s Topside, was typical of what could be found on the island fortress. Cheney featured two 12-inch guns mounted on “disappearing” carriages. When ready to be fired, counterweights suspended under a gun would raise it into firing position. This placed the long barrel “snout” over the reinforced concrete parapet, a position called “in battery.”

When one of the guns was fired, the recoil pushed the barrel backward and below the parapet, sheltering it from enemy shells. In this “crouched” position, called “from battery,” it could be reloaded. There was a lower level to each gun position that contained the battery’s magazine. Ammunition was brought from the lower level to the upper level by electrically powered chain hoists.

Battery Cheney’s upper level included not only two gun platforms, but also observing stations, a plotting room, and the battery commander’s station. Like the other batteries on the island, Cheney was built when air power was in its infancy. Large concrete emplacements like Cheney were vulnerable not only to air attack, but also to land attack, should enemy infantry manage to set foot on the island.

Though Corregidor consumed much time, money, and energy, the other Manila Bay islands were not neglected. Carabao Island, just off Cavite Province, was also fortified and named Fort Frank. In similar fashion, several batteries were constructed on Fort Hughes, formerly known as Caballo Island.

Perhaps the most unusual fortification was Fort Drum, located on El Fraile Island. In essence, the top part of the island was scraped away and replaced with a large reinforced concrete structure so formidable it was nicknamed “the concrete battleship.” Fort Drum featured two twin 14-inch guns in special turret mounts. Battery Wilson was the upper turret, while Battery Marshal was the lower turret.

Fort Drum also bristled with 6-inch artillery and 3-inch antiaircraft guns, and its main structure boasted steel-reinforced concrete that was 25 to 36 feet thick. The “concrete battleship” proved one of the most effective tools for the defense in the coming campaign. A tough nut to crack, it would resist repeated Japanese artillery and bombing attacks. Its formidable guns could fire at both Bataan and Cavite with relative ease.

The island fortresses of the Philippine Coast Artillery Command were headed by Maj. Gen. George F. Moore and consisted of three coastal artillery regiments: the 59th, the 91st Philippine Scouts, and the 92nd Philippine Scouts. These were supplemented by one antiaircraft unit, the 60th. When the war broke out there were also about 600 Filipino soldiers training to become artillerymen. They were attached to the Philippine Scouts.

Though the Manila harbor defenses were the best of their time, changing technology and shifting political and economic currents served to undermine their effectiveness. The Washington Naval Treaty specifically forbade construction of additional fortifications and prohibited the modernization and upgrading of existing ones. The Great Depression of the 1930s made inroads on military budgets, with Congress adopting a penny wise, pound foolish series of cuts that did much to curtail the expansion of the U.S. armed forces.

The Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 further extinguished the last hope of modernizing the harbor defenses. The measure granted independence to the Philippines in 10 years (later amended to 1946). Congress saw little reason to spend American tax dollars on what would soon become a “foreign” country.

Attitudes changed in the late 1930s when it was obvious that Japan and the United States were on a collision course. Malinta (“Full of Leeches” in Filipino) Tunnel was dug under Malinta Hill; it consisted of a 1,400-foot-long, 30-foot-wide main passage augmented by 25 laterals, each 400 feet in length. The subterranean complex was reinforced with concrete walls, floors, and overhead arches, blowers to furnish fresh air, and an electric car line along the east-west main passage.

In 1937 Corregidor’s defenses were bolstered by the addition of 155mm tractor-drawn guns and 3-inch antiaircraft batteries. A beach defense plan was finally arranged, 75mm guns were deployed, and barbed wire strung in vulnerable areas. All the coastal artillery regiments were brought up to strength, though many of the men manning them were raw recruits.

General Douglas MacArthur was originally sent to the islands in 1935 (with Major Dwight D. Eisenhower as his chief military aide) to act as an adviser to the semi-independent Commonwealth of the Philippines under President Manuel L. Quezón. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt was happy to see MacArthur go because he felt the general was a dangerously ambitious man and a possible political rival.

In 1941, with war plainly on the horizon, Roosevelt federalized the newly forming Philippine Army and simultaneously made MacArthur commander of the United States Army Forces, Far East. MacArthur had some 80,000 men on Luzon, but most were raw Filipino recruits fresh from island farms and villages. Many of them didn’t even speak the local Tagalog language, much less English, but had various native languages of their own. The backbone of MacArthur’s forces was about 12,000 Americans, including the 31st Infantry Regiment, and about 13,000 crack Philippine Scouts.

MacArthur was in a race against time—and time was plainly running out. When Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, Philippine defense preparations were still incomplete. And Japan was preparing to invade.

General Homma’s 14th Army, consisting of over 40,000 men, sailed from Formosa and other debarkation ports on December 17, 1941, and, after much initial confusion on the morning of December 22, landed at several points along the western shore of Lingayen Gulf. American warplanes attempted to halt the invasion, but their efforts were unsuccessful, as were the efforts of U.S. and Philippine ground troops in the area; Homma’s men advanced with little real opposition, at least at first.

Mauled by the overpowering invasion, the Lingayen Gulf defenders had no alternative but to fall back into the Bataan Peninsula and try to hold out until help came. It was a logistical nightmare from the first because some 100,000 people, including many civilian refugees and dependents of Filipino soldiers, crammed into the tiny peninsula. Bataan was a wild region, thick with jungle and laced with soaring mountain peaks. Food became scarce, and tropical diseases lurked everywhere.

On December 23, Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, commander of U.S. forces in the area, telephoned MacArthur’s headquarters at Manila, explaining that further defense of the Lingayen beaches was “impracticable.” He requested permission to withdraw behind the Agno River, a request that was quickly granted.

The next day, another smaller invasion force led by Lt. Gen. Susumu Morioka came ashore at three points along Lamon Bay. With Homma’s army heading south from Lingayen Gulf and Morioka’s 16th Division moving north, Manila was about to be caught in a vise.

But the Japanese soon found that American and Filipino resistance stiffened with every hard-fought mile. For the next four months the Filipinos and Americans, weakened by hunger and disease, would conduct a courageous holding action against the odds. As the weeks wore on, optimism faded, and even MacArthur’s bombastic “help is on the way” communiqués could not mask the grim realization that the Philippines had been written off.

Corregidor, far behind the lines in the early stages of the campaign, got its first taste of war on December 29, 1941. Shortly before noon, Japanese medium bombers appeared over the island like sinister birds of prey, dropping their 225- and 550-pound bombs from an altitude of 15,000 feet.

Air-raid sirens wailed, but at first many of the men took little notice. There had been false alarms before, and Corregidor’s many buildings—never mind its bomb shelters—were said to be blast proof. The myth of Corregidor’s invulnerability soon vanished in in flame and smoke.

Marine Private Warren “Jorgy” Jorgenson was having lunch with his buddies when all hell broke loose. “As we spilled out of the galley,” Jorgenson remembers, “Corregidor’s antiaircraft guns were already opening up. A hasty glance at the sky showed formations of high-flying bombers proceeding … silvery in the sun and clear blue sky, approaching directly overhead.”

Donald Versaw had just finished a work detail, washing down the area behind the barracks mess hall. It was a nice, sunny winter day, and Versaw softly whistled “Lady Be Good” as he glanced up into the sky. The young leatherneck then caught a glimpse of Japanese bombers flying in a “V” formation “like geese” when the air-raid sirens started screaming out their warnings.

Versaw found shelter of sorts in a small wooden building, and from the windows “looking up through the trees, I could see enemy planes flying overhead and sticks of bombs falling, tumbling down from them.”

The bombing lasted over two hours, with formation after formation peppering the island with explosives. After the Japanese Army bombers were finished, naval aircraft from the Japanese 11th Air Fleet came in and dropped their payloads. Casualties were light, but Topside and Middleside barracks, the Officer’s Club, the hospital, and the Navy fuel depot were destroyed or damaged.

Fires raged as wooden buildings were consumed, and thick, black coils of smoke rose high into the air. The 3-inch antiaircraft batteries, supported by machine-gun fire, had performed well. Thirteen Japanese planes were shot down, including nine heavy bombers. After this, Japanese aircraft—dive bombers were the exception—tended to fly above 24,000 feet to avoid the antiaircraft fire.

Periodic bombing continued for the next four days, but after that there were several lulls. In the whole month of January there were only two additional raids, much to the relief of the weary garrison. On January 29 the Japanese bombers returned, but with a paper barrage—propaganda leaflets urging surrender. It was said the men welcomed the leaflets because they came in handy as toilet paper.

Technically, the 4th Marines were responsible for beach defenses, but as the weeks and months wore on, leatherneck ranks were swelled by sailors, soldiers, Army Air Force pilots who didn’t have planes, Philippine Scouts, and many, many others. Colonel Samuel Howard, who had commanded the 4th Marines in Shanghai, was formally placed in charge of Corregidor’s beach defenses.

Corregidor wasn’t yet under full siege. Small ships brought in a trickle of supplies until mid-February, when the Japanese blockade finally became more effective. Even after this time, the island fortress was visited by U.S. submarines that brought in medicine and a few necessities. The “silent service” boats also evacuated personnel, such as U.S. Commissioner Francis B. Sayre and Philippine President Manuel L. Quezón. Also, the Philippines’ gold and currency reserves were removed to Corregidor; the national treasury was evacuated by the American submarine USSTroutand taken to Pearl Harbor for safekeeping.

During lulls in the bombing, the men dug additional foxholes, strung barbed wire, and improvised additional defensive measures. Private Versaw was with E Company, 2nd Battalion, on the bulbous “tadpole” head of Corregidor. Versaw and his companions were in foxholes along South Shore Road atop jagged cliffs from Geary Point to the end of the road at Battery Monja, where two 155mm guns were emplaced. Some stretches of the road had permanent, concrete-lined trenches along them, and also metal-domed storage areas.

Curious, Versaw and some others of E Company looked inside one of the storage areas and found ammunition boxes. When the boxes were opened, they were found to contain bandoliers of .30-caliber ammunition of a kind that was used for the 1903 Springfield rifles. Since the Marines and soldiers were all carrying Springfields, at first it would seem this was an unexpected bonanza. Unfortunately, the ammunition had deteriorated to such an extent that bullets would fall out of their shell casings.

“The date on the boxes was 1921,” Versaw remembers. “I don’t think those boxes saw fresh air since 1922.” It was yet another example, albeit in microcosm, of the penny pinching that had plagued the military for decades. Yet, necessity is truly the mother of invention. Since the Marines of 2nd Battalion were perched on high cliffs, 25-pound fragmentation aerial bombs were used in a new way.

As Versaw recalls, “Wooden troughs were constructed, complete with wire rigging to suspend them from cliff edges over the beaches. To use it, a bomb would be put in the trough, then you’d tie arming wires to a screw at the top and give it a shove, sending the bomb down to the unsuspecting enemy on the beaches below.” The contraptions were never used, since the Japanese never scaled the cliffs.

On February 5, 1942, a new phase of the fighting began. While the Japanese attack on Bataan had been blunted by a stubborn and courageous Filipino-American defense, the enemy had access to the southern shores of Manila Bay on Cavite Province. Major Toshinori Kondo’s detachment of four 105mm guns and two 150mm cannons deployed near Ternate and opened up on Corregidor, Fort Frank, and Fort Drum.

American guns roared to life, flaming in counterbattery, inaugurating a gun duel that lasted a good three hours. It was the start of a contest that would continue on and off for the next two months. The garrisons at Corregidor, Fort Frank, and Fort Drum soon found that they were at a decided disadvantage when trading shots with the enemy.

For one thing, the big coastal artillery guns were designed to slug it out with ships, not land artillery. Most of the big guns—like the 12-inchers—simply didn’t have the elevation needed to clear the high ground where enemy artillery was located. Only the mortars, with their high trajectory, could be effectively used, but even in this instance problems arose.

There was plenty of ammunition available, but much of it was the armor-piercing, fixed, delayed-fuse variety. These were of a type that in essence burrowed deep into a ship’s deck or other structure before detonating. But on land, they simply buried themselves deep underground, and when they exploded did little damage to enemy equipment or personnel.

What was needed was antipersonnel instantaneous fuse ammunition, something that would quickly explode in the very midst of an enemy battery and wreak havoc. The island forts did have such ammunition, but only about 1,000 shells. Understandably, Colonel Paul Bunker, who was in charge of the guns, wanted to save those shells in the event the Japanese broke through at Bataan.

Bunker improvised, modifying the fuses of some 1,070-pound mortar shells by removing their .05-second delay pellets. That meant they could detonate faster and could be more effective when used against the Japanese guns at Cavite. But there were still problems in spotting the enemy positions, in part because of a shortage of sound-ranging equipment.

On February 9, 1942, Captain Jesus Villamor of the Philippine Army Air Corps took off from Corregidor’s Kindley Field piloting a slow Stearman 76D3 biplane and accompanied by five Curtiss P40E Warhawk fighters as escort. His mission was to fly a photo recon mission over Ternate to reveal the Japanese batteries there.

Even though he had an escort, his flight was an act of almost suicidal bravery. Villamor flew over the target area and managed to take enough pictures to deem the mission a success. But when he was returning, he and his escorts were intercepted by six Nakajima Ki-27 “Nate” fighters. A furious dogfight ensued, and though one P-40 was lost, at least one Japanese plane, and perhaps as many as five or six (accounts disagree), were downed.

Villamor landed, and once the film was developed the information it provided was extremely helpful. Several direct hits were scored at Ternate, but unfortunately the Japanese moved their batteries to the more remote hills to get out of range.

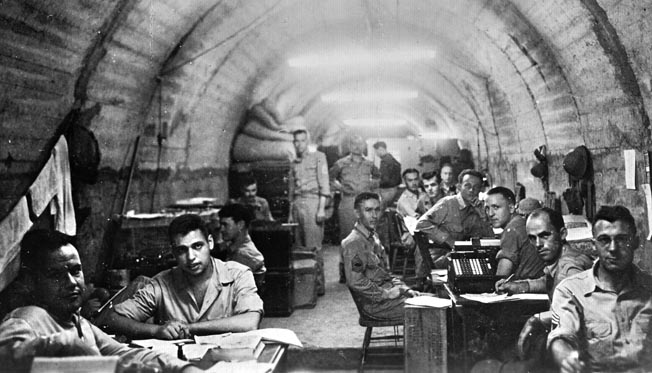

Malinta Tunnel was in many respects the heart of the fortress island’s defense system. It became General MacArthur’s headquarters after he left Manila and also housed the main communication center with the outside world. To the Marines, sailors, and soldiers huddled in foxholes, the staff that inhabited the Malinta Tunnel were privileged characters, eating well, hobnobbing with the brass, and saving their skins by rarely leaving the tunnel.

They were dubbed “Tunnel Rats” by the others, the name bestowed with a mixture of contempt and possible envy. Jokes were circulated about how Malinta Tunnel occupants would receive a “DTS” medal minted specially for them—“Distinguished Tunnel Service.” The subterranean life of Malinta Tunnel was indeed a different world, but far from the paradise that many outsiders imagined.

The tunnel was overcrowded, with the situation becoming worse with each passing day as wounded were brought into the underground hospital. The ventilation system was overtaxed, and most of the fresh air from the entrances was blocked by concrete flash walls, erected to prevent the Japanese from skipping a bomb into the tunnel. Each of the smaller laterals housed two dozen or more people, who shared one toilet and one small washbasin.

Newcomers found the stench of the place nauseating. Carlos Romulo remembers, “There was the stench of sweat, or dirty clothes, the coppery smell of blood and disinfectant from the lateral where the hospital was located, and over all the stink of creosote, hanging in the air like a blanket.”

The air was foul and damp, a kind of hothouse atmosphere that made normal breathing a challenge. Army staffers, Filipino government officials, clerks, nurses, refugee civilians, and many others rubbed shoulders in the dank, poorly lit gloom. Sleep was almost impossible as the rumble of artillery and muffled thunder of shells crashing outside combined with the clacking of office typewriters and the moans and screams of the wounded.

Though the hospital was generally well stocked with medicines and equipment, the overcrowded conditions and troglodyte atmosphere made it more like a circle of Dante’s Inferno than a place of refuge and healing. Marine “Jorgy” Jorgenson, who was wounded when the Japanese finally came ashore in May, recalls that the atmosphere was “hot and stifling, with the smell of gangrene and ether from the hospital lateral where the survivors of Battery Geary were.”

General Douglas MacArthur, one of the most famous and controversial figures to emerge in World War II, lived and worked in these tunnels. MacArthur was a great general, one of America’s best, a man capable of real strategic brilliance. Flamboyant and larger than life, handsome and egotistical, he had a talent for both making enemies and attracting admirers.

All humans have strengths and weaknesses, but MacArthur’s very prominence brought his faults out in high relief, and the Philippine campaign of 1941-1942 showed aspects of MacArthur’s negative side. In his 77 days on Corregidor, he only visited the Bataan battlefront once, on January 10, 1942. Of the 142 communiqués issued by his headquarters, it is said he was mentioned 109 times. And though others share the blame, MacArthur allowed virtually all of the U.S. Army Air Corps planes to be destroyed at the Philippines’ Clark Field, even though he had had warning of the Pearl Harbor attack some nine hours before.

In fairness, MacArthur did his best to persuade Washington to send help, although he probably sensed the effort was doomed from the start. The general also shared the hardships to some extent, losing 25 pounds because of the scanty rations. But MacArthur had become the very symbol of American resistance to Japanese aggression. It was unthinkable that he would be captured.

On February 22, 1942, Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to transfer his headquarters from the Philippines to Australia before the defenses fell; on March 11-12, the general, his family, and a small group of staff officers departed Corregidor by PT boat. It was during this trip that MacArthur made his famous “I shall return” vow. Once settled in Australia, MacArthur was named Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area.

In the meantime, life for those still on Corregidor went grimly forward. Rations were cut, though some units fared a bit better than others by foraging and improvising. Occasionally there was some canned fruit, like peaches or pineapple. If they were lucky, Corregidor’s defenders might get a pancake or two or a bit of Spam-like meat. By the end of April, even these goods were getting low and were scrupulously rationed.

“We were lucky,” Don Versaw admits, “because the troops on Bataan weren’t getting hardly anything at all. We did get a slab of mule or horsemeat once or twice. It was very coarse and tough, and [tasted] kind of wild, but it was meat.”

There were few light moments on Corregidor but Marine mascot Soochow managed to provide a few laughs. The dog was originally a stray picked up on the streets of Shanghai, ugly as sin, but lively and intelligent. It was said that the dog was a kind of early warning system, barking like mad well before the air raid sirens began to wail. “Sooch” also had enough sense to stay with the Marines; if he had wandered off, he might have ended up in an Army cooking pot.

The Japanese forces tightened their noose around Corregidor. Now Corregidor and its satellite forts stood alone. Low on ammunition, food, and medicine, wracked with sickness and hunger, his men (and women, too) had done more than their duty. Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., commander of Luzon forces, ignored MacArthur’s last-minute, long-distance demand that he launch a counteroffensive.

Sadly aware of the hopelessness of the American position in the Philippines, President Roosevelt authorized Lt. Gen. Wainwright to either continue to hold out against the Japanese or seek terms for surrender as he saw fit. At his headquarters on Corregidor, a long-suffering and hard-fighting Wainwright initially elected to follow MacArthur’s order from Australia to continue the unwinnable battle to the end.

On April 9, 1942, after four months of bitter fighting, General King surrendered Filipino-American forces on the Bataan peninsula. Instead of treating their captives with respect and compassion as demanded by the rules of warfare, the Japanese, infuriated by the stubborn resistance on Bataan and the heavy losses they had themselves suffered, vented their rage on their sick and exhausted prisoners of war. Rather than being accorded the opportunity to sit out the war in a POW camp, the prisoners were marched into the jungle––a journey of brutality aptly called the Bataan Death March, where thousands died. Those who survived were then imprisoned under deplorable conditions.

Once Bataan had fallen, it was only a matter of time before Corregidor would be taken, too. Some soldiers from Bataan managed to escape to Corregidor until there were an estimated 10,000 to 14,000 people on the island fortress enduring ceaseless, round-the-clock artillery barrages.

Japanese General Homma was a man in a hurry. The Philippine campaign was supposed to have lasted 60 days—it was now over four months, and the Americans were still resisting. He was losing face, but he also feared he might be relieved of 14th Army command. Homma was determined to reduce Corregidor as soon as possible.

At first the Japanese seemed overconfident. They placed a battery of 75mm guns in plain view of American spotters and began to lob shells at the island. Corregidor’s Battery Kysor replied with its 155s and scored a direct hit. The Japanese guns and their crews were blown sky high.

The first phase of the Battle of Corregidor began with an artillery duel on April 12. Battery Geary, under the command of Captain Thomas W. Davis III, hammered the enemy with great success. Geary’s mortar shells first rained down on a Japanese battery near Lokanin Point, destroying it utterly. A short time later, American 670-pound mortar shells annihilated another battery and blew up an ammunition dump.

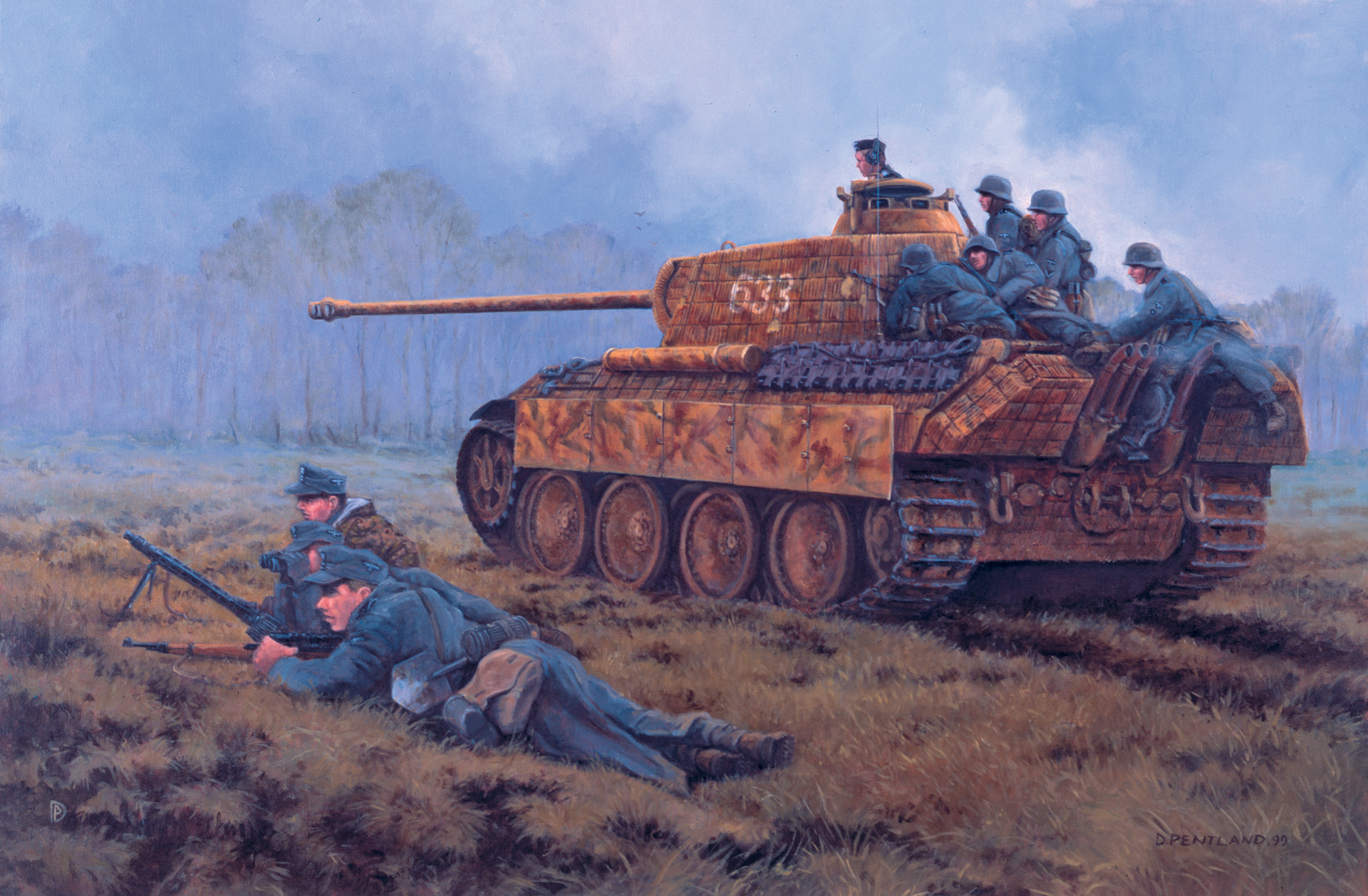

To cap the day’s successes, Battery Geary turned its attention to a group of Japanese tanks from the 7th Tank Regiment that had foolishly parked out in the open. Mortar shells pounded the area, leaving several blackened and burning wrecks in their wake. But this good fortune was not to last.

No less than 18 Japanese batteries were soon in place on both sides of the channel into Manila Bay––altogether some 116 artillery pieces. But perhaps the most destructive were the 240mm guns, whose heavy explosives began to slowly chip away at Corregidor’s major batteries. On April 24, Battery Crockett was knocked out; both of its guns were put out of commission, the ammunition hoists were ruined, and whole sections of the emplacement were engulfed in flames.

Crockett’s ordeal was highlighted by the exceptional courage of its doctor, 59th Coast Artillery surgeon Captain Lester Fox. When fires reached the hoist room and several men had been wounded, Dr. Fox came forward to render aid. A shellburst broke his leg, but he managed to limp around enough to organize a fire control party. This was crucial, since flames were threatening the powder magazine.

More shells descended on Crockett, and Fox was wounded again and again but continued his duties. He survived and later recalled, “I was wounded repeatedly; in the right eyebrow, losing the sight of my right eye, fracturing several ribs and generally making me very mad.” Dr. Fox was eventually carried to the Malinta Tunnel hospital, where he later became a POW.

Day after nerve-shattering day, the shelling continued, with the attacks supplemented by frequent bombing runs by the Japanese Air Force. On May 1, 1942, some 3,600 Japanese shells pummeled the area around Batteries Cheney and Geary, many of them the horrific 240mm variety. One by one the batteries around the beleaguered island were badly damaged or totally knocked out. Repairs were made when possible, but it was a hopeless task.

On May 2 the Japanese bombardment intensified. During one five-hour period, the enemy gunners pounded Topside with a dozen 240mm shells a minute, a total of 3,600 rounds.

Battery Geary sustained the worst damage when a 240mm shell broke through the concrete side of its powder magazine, already pockmarked with numerous earlier hits. When the shell exploded, it detonated 1,600 62-pound powder charges. The resulting explosion shook the island like an earthquake, producing a malevolent mushroom of flame and smoke that tossed 13-ton mortars like they were children’s toys. One mortar actually flew 150 yards into the air, landing muzzle down in the soft, yielding ground of the island’s golf course. Miraculously, only six crewmen were killed and another six wounded, but Battery Geary’s eight mortars were destroyed and played no further part in the battle.

By the end of the first week in May the handwriting was on the wall—Corregidor was going to fall. General Wainwright considered his options. Although many batteries were knocked out, enough remained to put up a pretty good fight if the Japanese invaded the island. Ammunition was fairly plentiful, and with careful rationing the food could last until the end of June.

Diesel fuel was running low, and that was a critical problem because the water pumping system needed it to draw water from Corregidor’s wells. This fuel would run out mid-May, and then the garrison would have no water. Wainwright’s main mission, at least as he saw it, was to try and sustain morale and hold out, tying up as many Japanese troops as possible.

Wainwright had a chance to escape when Major Bill Bradford took the last flight out of Corregidor’s Kindley Field. Bradford had taken several of these risky flights, flying at night and evacuating a number of people, including two civilian war correspondents. Wainwright was urged by his senior staff officers to follow MacArthur’s example and escape, but he refused, saying, “I have been with my men from the start, and if captured, I will share their lot.” Later, when Wainwright surrendered Corregidor, MacArthur called him “unbalanced” and refused to endorse a Medal of Honor recommendation for the doomed commander.

Wainwright became a beloved figure, making the rounds at the hospital or chatting freely with groups of soldiers. It was something that the imperious and “godlike” MacArthur would never do. Yet Wainwright still hoped to evacuate some personnel, particularly the Army nurses, before the island’s inevitable surrender.

The USS Spearfish,with skipper Lt. Cmdr. Jim Dempsey, was the last submarine to visit Corregidor. It left on May 3 with 25 evacuees, including 12 Army nurses. Now it was only a matter of time. The garrisons on Corregidor and the smaller fortress islands awaited their fate.

The Japanese planned to land on Corregidor the night of May 5. The assault would be led by Colonel Gempachi Sato’s 1st and 2nd Battalions, 61st Infantry, supported by tanks of the 7th Tank Regiment. The original idea was to land on Corregidor’s tail between North Point and Infantry Point. Once a beachhead was established, a second group would come ashore.

The Japanese troops were in fine spirits and, as they boarded their landing craft, they sang the high, thin, haunting melody of “Prayer in the Dawn.”

There was no standard size to the Japanese vessels; some carried as few as 30, while others carried as many as 170. The coxswains from the 21st Engineer Regiment guided their landing craft toward the looming bulk of Corregidor, confident that all would go according to plan.

Defense of Corregidor’s eastern end fell to the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, under the command of Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher. Though nominally a Marine battalion, the force included about 360 Marines, perhaps 100 U.S. Navy sailors, a company of the 803rd Engineers, 240 Philippine Scouts of the 91st and 92nd Coast Artillery, some Philippine Army Air Force men, and even a few Filipino mess boys. This conglomeration totaled 1,024 men in all.

Weapons were running low. The 1903 Springfield rifle was the standard armament, supplemented by Browning Automatic Rifles, four 37mm guns, and eight .30-caliber machine guns. A few 60mm mortars were on hand, as well as some .50-caliber machine guns salvaged from scuttled Navy ships. The Philippine Scouts also had a few 75mm artillery pieces available.

The 1st Battalion was divided into A Company, B Company, and Weapons Company D. Company A, 4th Marines, was given the task of defending 21/2miles of Corregidor’s north shore. Commanded by Marine Captain Lewis Pickup, they faced the three-mile stretch of water that separated the island from the Bataan peninsula. They would be the first to engage the enemy.

By contrast Company B, commanded by Lieutenant Alan Manning, was assigned the south shore, though it would later find themselves heavily engaged in the coming fight. Captain Noel Castle’s Weapons Company D was ready to give support wherever it was needed with heavy machine guns and 37mms.

The amphibious assault was preceded by a massive bombardment of Company A’s positions along Corregidor’s snaking tail. So many shells rained down that the whole eastern end of the island seemed to be one continuous curtain of smoke and flame. In theory, the first Japanese wave was supposed to hit the Corregidor beaches at 11 pm, but the plan began to unravel almost at once.

The overconfident coxswains discovered to their horror that Corregidor’s familiar landmarks, so distinctive from Bataan, disappeared as the landing craft got closer. Heavy smoke from the bombardment also tended to obscure the proposed beachheads. But most of all a very strong current pushed the landing craft much father east then they originally planned.

Sergeant John F. Hamrich’s squad of Company A, posted near Cavalry Point, could just make out dim shapes on the water—the first approaching landing craft. It was 11:10 in the evening, and someone shouted, “Here they come!” in the darkness. Company A needed no prompting, or even a formal order to commence fire. All along the north shore beaches, the Americans and Filipinos opened up with everything they had. Springfield rifles shot clip after clip into the enemy until barrels grew almost too hot, while .30- and .50-caliber machine guns sprayed the landing craft with a hurricane of lead.

Artillery opened up as well, including 75s and 37mm guns. The moon had yet to rise, and whenever an American searchlight was turned on it was quickly put out of action by Japanese fire. But the Americans found that their machine-gun tracer bullets gave more than enough light for the task at hand.

Japanese soldiers scrambled ashore only to be cut down “like falling dominoes.” Though the defenders had little love for the Japanese, at least some recalled it was a “sickening slaughter.” The Japanese were also hampered by the gooey oil that clung to the shoreline, detritus of the many ships that had been damaged or sunk in Manila Bay.

In other parts of the defense line, Marines supplemented their machine-gun and rifle fire with grenades and even improvised Molotov cocktails. Some Japanese units were in such dire straits the English speakers among them shouted over the machine-gun chatter and grenade blasts, pleading for mercy and insisting they were really Filipinos. These ruses were ineffective.

But Company A’s defensive line was thin in spots and gradually the Japanese managed to push through and establish a beachhead. As Marine Private Alvin Mack remembered, “There were so many of them, we couldn’t handle them all. They overran us.” Once the beachhead was consolidated, Colonel Sato and his men gingerly probed north, toward Malinta Hill.

Jorgy Jorgenson of Company B remembers the Japanese landing well: “We were alerted by runner (no phones or radios) that the sound of landing craft had been heard approaching from the direction of Bataan.” Jorgenson’s unit headed out toward Monkey Point, where the Japanese were said to be landed. But as they pushed forward, they discovered the Japanese—at least some of them—had infiltrated in the darkness and confusion and were much closer than expected.

Company B took cover and engaged in a furious firefight with the enemy. Then good news filtered through the company positions—Weapons Company D was coming with its machine guns and mortars to support them. After Company D joined the fray, a pale moon finally appeared, bathing the battlefield with a soft light. Jorgenson looked around just in time to see the Company D commander, Captain Noel Castle, take a bullet or bullets and fall to the ground dead.

Since it was fought in the semi-dark amid a blasted and rubble-filled landscape, the battle was confused and bloody. At times it was hand to hand, and the bayonet was freely used when necessary. The Americans did their best to dislodge the Japanese, but the beachhead stood firm.

The battle continued through the night and into the next morning. Jorgy and the rest of Company B were about 250-300 yards from a damaged water tank, pouring whatever fire they could into the Japanese soldiers dug in around it. It grew lighter, and daybreak finally made what must have seemed a belated appearance to the exhausted defenders.

Jorgenson’s sergeant ordered “fix bayonets!” but before Jorgy could comply, “I experienced an intense, searing pain in my left side and realized I’d been hit.” Jorgenson managed to get to a nearby corpsman, who dressed the wound but could do no more. The young Marine had to make it back to Malinta Tunnel as best he could.

By mid-morning on May 6, the situation was no longer in doubt. The Japanese were firmly ensconced on Corregidor, despite heroic efforts to keep them off. With much difficulty they managed to land tanks on the island, a fact that finally made Wainwright think of surrender. He feared that the tanks would pour fire into the crowded main tunnel and its laterals, which would result in wholesale slaughter.

The surrender was particularly hard on the Marines. The regimental colors were burned to prevent capture. Colonel Samuel Howard, the regimental CO, broke down and wept, lamenting that he was the first Marine officer ever to surrender a regiment. All the garrison—some 14,000 persons—became POWs, and many later endured torture and starvation as slave laborers in Japan.

But Corregidor, like Bataan, stands as a symbol of American and Filipino courage in the face of overwhelming odds. Today the Philippines commemorates April 9, the day Bataan surrendered, as a national holiday called Day of Valor. Corregidor, too, is enshrined in history as a place where men were tested, but not found wanting.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments