By John W. Osborn, Jr.

Without warning, from behind his desk in his miniature coliseum of an office in Rome’s Palazzo Venezia, Benito Mussolini on the morning of May 26, 1940, pronounced those words that were to prove fateful for Italy, fatal for him: “I have sent Hitler a written statement, making it clear to him that I do not intend to stand idly by and that from June 5th I shall be in a position to declare war on France and England.”

Mussolini had no reason to expect an argument from the officer his words were directed to, Pietro Badoglio—he was a shameless opportunist always able to convince himself he was acting in Italy’s interest instead of his own. When Mussolini was marching on Rome in 1922, then chief of staff, Badoglio had offered to disperse the Blackshirts with five minutes of machine-gun fire. Yet after Mussolini shipped him to effective exile as ambassador to Brazil,

Badoglio quickly convinced himself that Italy needed Mussolini’s leadership and Mussolini needed his services. For his newly found devotion to the Duce he had been properly paid off; he served as chief of staff again, was elevated to the rank of marshal, commanded the invasion of Ethiopia, and was given a dukedom with appropriate villa and income.

However, Badoglio was also a survivor of Italy’s worst military disasters, the Battles of Adowa and Caporetto. He could see looming before him the most catastrophic of all. “Your Excellency,” he nervously started, “you know perfectly well that we are absolutely unprepared—you have received complete reports every week.”

Badoglio was talking to a leader who paid so little attention to the rudiments of actually governing that he signed piles of documents without bothering to read them—ministries often getting conflicting orders as a result. As he tried to reveal the truth behind the propaganda that Mussolini always preferred, Badoglio grew increasingly agitated, then finally exploded: “THIS IS SUICIDE!”

As he had listened, Mussolini scowled, and then his face reddened. He suddenly rose, strode around his desk with clenched fist, and thumped Badoglio’s chest so hard the head-taller marshal almost toppled over. “You are not calm enough to judge the situation, marshal. I can tell you that everything will be over by September, and that I need only a few thousand dead to sit at the conference table as a belligerent.”

Instead, Benito Mussolini was to find only defeat and death after international scorn and humiliation in one of the most forgotten campaigns of World War II, his 15-day war with France.

Mussolini’s march to war had begun a year earlier with the signing of the Pact of Steel, the alliance with Hitler. He had already thrown around as much of his own weight as he was able in conquering Ethiopia, intervening in the Spanish Civil War, and occupying Albania. Now he saw his future at Hitler’s side as an equal partner.

“Now Germany cannot take decisions that don’t coincide with our interests,” said the deluded Duce.

Much less sure was the Duce’s minister en-trusted with foreign relations, whose only qualification was a family connection to the dictator.

When he was appointed by Mussolini to be foreign minister in 1936 at age 33, Count Galeazzo Ciano brought to the job the thinnest of résumés—including minor diplomatic postings to South America and China—but the thickest of connections. His wife was Mussolini’s daughter. Though he doubted the very basis of the policy he was charged with executing, Ciano was too ambitious, cynical, and corrupt to ever consider throwing away the power and perks—including women—that that happily came with the job over such an inconsequential matter as principle.

When not performing his diplomatic double-dealing or cavorting with the earlyla dolce vita crowd (including cocaine supplied by the American Mafioso Vito Genovese, then hiding from a murder charge back in New York), Ciano’s only worthwhile activity was keeping a diary candidly describing the foibles and flaws of his father-in-law and everyone else except himself.

Article III of the Pact of Steel committed Italy to going to war on Germany’s side. Ciano’s Nazi counterpart, Joachim von Ribbentrop, with whom he was locked in a mutual loathing as strong as their leaders’ regard for each other, assured him that there would be no war until 1942. Yet the very next day Hitler secretly ordered preparations for the invasion of Poland.

“They have betrayed us and lied to us,” Ciano stated. Under pressure by Ciano and the military, Mussolini reluctantly, humiliatingly, squirmed out of the alliance by sending Hitler an offer. “Whatever figure your department gives us, double it,” Ciano directed for the immediate delivery of 17 million tons of war supplies. “I shall not need Italian military aid,” Hitler, tersely, mercifully, answered.

Mussolini grudgingly proclaimed Italy a non-belligerent. “He does not want to utter the word ‘neutrality,’” Ciano noted but bitterly complained the policy was reducing Italy “to the level of a tenfold Switzerland.” Returning from meeting Hitler at the Brenner Pass in March 1940, Mussolini told Ciano he would base his policy after an Italian Robin Hood, who persuaded his hangman to let him pick the tree. “Needless to say, he never found the tree. I shall reserve for myself the choice of the moment. I alone shall be the judge, and a great deal will depend on how the war goes.”

It was soon going spectacularly well for Hitler. With the French on the brink of defeat and the British rushing for Dunkirk, Mussolini called in Ciano to say there was no time to lose and he would declare war in a month. “I did not answer,” Ciano confided to his diary. “Unfortunately I can do nothing now to hold the Duce back. He has decided to act, and act he will.” He left the protesting, for what it was worth, to the likes of Pietro Badoglio.

Mussolini waited two weeks to have his stormy session with Badoglio. Three days later, he formalized it by inaugurating the Commando Supremo, thus usurping the constitutional role of King Victor Emmanuel III and making himself commander in chief. “Rarely have I seen Mussolini so happy,” Ciano reflected. “He has realized his dream: that of becoming the military leader of his country at war.” His joy, though, was not shared by the military, which had the burden of turning his dream into reality.

With tragic understatement, one general commented, “Our situation was not brilliant.” The army’s standard rifle was 50 years old. Of 73 divisions, just 19 were at full strength, the next 20 were at 70 percent, the rest at 50 percent or less.

A subordinate suggested Badoglio resign in protest to make Mussolini face reality. As ever, the mealy-mouthed marshal, his moment of outrage now behind him, was quick to put career before country while convincing himself he was doing the opposite. “I believe there is really no more to be done. Besides, who knows? Perhaps Mussolini is right. Certainly the Germans are extremely strong, and they might be able to win a quick victory.”

Appeals from President Franklin Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and French Premier Paul Reynaud to stay out of the war were brusquely brushed aside, but Mussolini dutifully delayed five days at Hitler’s request. Finally, with no turning back, France’s Ambassador André François-Ponchet was grimly facing Ciano in his office inside the Palazzo Venezia late in the afternoon of June 10, 1940.

“I expect you understand the reason for your being called?” Ciano, in air force uniform, he had led a bomber squadron in Ethiopia and just taken command of another, stiffly inquired.

“I am not too bright, but this time I have not misunderstood the situation.”

Ciano read out the declaration of war. “It is a dagger thrust into a fallen man. Thank you all the same for using a velvet glove,” François-Ponchet responded. “The Germans are hard masters. You, too, will learn this. Don’t get killed,” He warned, pointing to Ciano’s uniform.

With the bombast he always mistook for eloquence, Mussolini bellowed the news of Italy’s entrance into World War II from his beloved balcony.

“It was a pitiable spectacle,” Badoglio said later. “Herded like sheep between the officials and riff-raff of the Fascist Party, the crowd had orders to applaud every word of the speech. But when it was over, the people dispersed of their own accord in complete silence.”

Hardly less depressed was Galeazzo Ciano. “I am sad, very sad,” he confided to his diary. “The adventure begins. May God help Italy!”

“What really distinguished, noble, and admirable people the Italians are to stab us in the back at this moment!” Premier Reynaud in Paris fumed to American Ambassador William Bullitt. Bullitt cabled Reynaud’s words to Washington, where it was still early morning on June 10, and President Roosevelt decided to use them in his commencement speech that evening at the University of Virginia.

Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles cautioned that those words could wreck relations with Rome, and Roosevelt relented. On the way, though, “the old red blood said, ‘Use it,’” FDR recalled, and, with his anger and scorn plain to see, he flung those words that damned Benito Mussolini and Fascist Italy before the world: “On this tenth day of June, 1940, the hand that held the dagger has stuck it into the back of its neighbor.”

Yet if Mussolini had been in a rush to go to war, he was in no hurry to actually fight it. “After many years’ talk of fast offensive war, we are starting by standing fast on our frontiers, without a plan of operations, taking great care that we are not attacking,” one Italian general complained.

Mussolini’s unexpected inaction left even Hitler puzzled. “When the Duce told him he could not delay the announcement beyond June 11, he, Hitler, was convinced that Italy had prepared lightning moves against Corsica, Tunis, or Malta and that military secrecy prevented a delay,” the German military attaché in Rome remembered. “It reminded the Führer of what happened in the Middle Ages, when cities exchanged messages and nothing happened.”

In North Africa the French in Tunisia and Fascists in Libya chose not to wait, conducting air raids and assaults on border posts. After the British bombed Turin, Mussolini ordered a bombing campaign against southern France, and the Regia Aeronautica would fly 1,337 sorties and 75 raids, dropping 726 tons of bombs.

Ciano left his desk to get in on the action: “Very bad weather; dangerous flying…. Accurate aiming. French reaction is also active and accurate.” In the end the Italians proved better at record keeping than at results, and little damage would be done.

The Italians did little better in air actions. Decades later Mussolini’s son remembered, “The reports about ‘flawless aeronautical equipment fully prepared to meet future challenges.’” In fact their most numerous plane, the Fiat CR.42 biplane, was an aerial antique.

Their most up-to-date fighters, and there were only 166 of them, the Fiat G.50 and Macchi 200, were still inferior to France’s Dewoitine, Bloch, and Morane-Saulnier aircraft, and it showed in aerial kills. The Italians claimed 10 downed Blochs, but lost 24 aircraft, seven alone downed by Sub-Lieutenant Pierre La Golan. Among them was the air war’s ranking casualty, the commanding officer of the 75th Squadrislia, Captain Luigi Filippi.

Events in France forced Mussolini to finally emerge from his inaction on June 15. With the British safely back across the English Channel and an appeal from Paris for an armistice expected at any moment, he again suddenly summoned Badoglio to order an attack along France’s Alpine frontier and fabled Riveria playground in just three days.

Again Badoglio protested, saying he needed at least 25 days. Again, Mussolini heard him out in silence and overrode him: “You are entitled to advise me on military topics, but not on political topics. The decision to attack France is a political one, and I alone bear the responsibility for it. If we merely look on while France collapses, we shall have no right to demand our share of the booty. I must have Nice, Corsica, and Tunisia.”

Again, it was Hitler who slowed him down. Two days later the French finally appealed for an armistice, and Mussolini found himself abruptly summoned to meet Hitler in Munich the next afternoon.

Mussolini and Ciano, back from his bombing, pulled out from Rome’s Termini station at 9 that evening. Both felt anxiety rather than anticipation. “Mussolini dissatisfied,” Ciano recorded in his ever-present diary. “This sudden peace disquiets him. During the trip we speak at length in order to clarify conditions under which the armistice is to be granted to the French.

“The Duce is an extremist. He would like to go as far as the total occupation of French territory and demand the surrender of the French fleet. But he is aware his opinion has only a consultative value.

“The war has been won by Hitler without any active military participation on the part of Italy and it is Hitler who will have the last word. This naturally disturbs and saddens Mussolini. His reflections on the Italian people and, above all, our armed forces are extremely bitter thus evening.”

The session went worse than Mussolini and Ciano could have imagined. It started at 4, finished by 6:30, and consisted of just informing them of the decisions Hitler had already made.

Mussolini’s own territorial demands, even just a seat at the armistice meeting, were brushed aside without discussion. “Mussolini is very much embarrassed,” Ciano noted. “In truth the Duce fears that the hour of peace is growing near and sees fading once again that unattainable dream of his life: glory on the field of battle.”

Mussolini was still determined to grab some while there was time by taking Nice. Rolling back into Rome at 6:15 the next night, he rushed straight to Palazzo Venezia and, despite reports that a freak, unseasonal, storm was burying the Alps in snow and plunging temperatures below zero, ordered an all-out attack for next morning, then headed to bed.

In the morning, to his fury, Mussolini found all that had been ordered were “small offensive operations immediately.” Mussolini had Badoglio on the carpet quickly, and a shouting match erupted between them.

In the end, as always, the irresistible force met the moveable object. At 9:10 that night the final order to 450,000 troops went out. Badoglio let his hated rival, Italy’s other marshal, Rodolfo Graziani, do the dishonors. He, at least, had no doubts: “When the guns start to go off, everything will automatically fall into place.”

Ciano had also absented himself with his jaded society cohorts. “I consider it rather inglorious to fall upon a defeated army and I find it morally dangerous also,” a unique reflection for him. “Armistice is at the door, and if our army should not overcome resistance during the first assault, we would end our campaign with a howling failure.”

Galeazzo Ciano had forecast the outcome of the war before it had started. For a quintet of soldiers the brief wintry war to follow was to be the first step to far more savage struggle in the snow. They would be lucky to survive.

Finally, at 3 am, June 21, 1940, Benito Mussolini began his march for glory—or least his few thousand dead. “Colonel Balocco is convinced it is going to be easy,” Eduardo Dutto, Cevi Battalion, First Alpino Regiment remembered years later. “Following is the regimental marching band.”

But Mussolini’s dreams were not those of the men tasked, or forced, to carry them out; nor did they have the confidence of Marshal Graziani or Colonel Balocco. “Some men cry, others curse,” Dutto bitterly recalled of Mussolini’s declaration of war. “We don’t even ask the reason for the war that’s about to start,” Michelangelo Pattoglio, 18th Company, Dronero Battalion, was lucky to be able to recall years later. “We aren’t interested in politics. No one wants to be a soldier.”

A captain in another battalion in the First Alpino Regiment, Guiseppe Lamberti, was reluctant for a different reason. “Our military machine is incapable of meeting not only the most basic demands of war but the very demands to sustain life in the units,” he angrily related. “The facts give the lie to the fictions. It’s all a bluff.”

The 1st Army in the south moved along the warm, scenic Mediterranean coast aiming for Nice and Marseilles, while in the north the 4th Army had the much harder time sloughing down the Little St. Bernard and other Alpine passes.

“The French patrols are few; they take a few shots, fall back. We walk on two meters of snow sinking halfway up our legs,” remembered Pattoglio.

“Three days always in the snow,” said Bartomelo Fruttero of the Dronero Battalion. “A struggle against the elements,” Captain Lamberti called it. “Landslides, rockslides. The effectiveness of the French artillery puts us to the test, too.”

Facing the Italians was the French Army of the Alps, 185,000 in number but not in strength—most of the men were rated “B” class. Their commanding general later ticked off World War II’s least known battlefields, and the odds facing his troops. “We were outnumbered seven-to-one at Tarentaise, four-to-one in Mauriene, three-to-one in Brianconnaise, twelve-to-one in Quevras, nine-to-one in Tinee, seven-to-one in L’Aution and Sospel, and four-to-one in Menton.”

But a young French lieutenant by the name of Bulle in the 7th Battalion, Chausseurs Alpins was not frightened by those odds. “My section will continue to prevent a passage through the Col ‘Enclave,” he defiantly vowed in a letter home. “We do not have many men but we shall hold on. As long as we have a single bullet left, no enemy soldier will break through the Col. Long live eternal France.”

Ciano’s worst fears were soon realized. “Today they [Italian troops] have not succeeded in advancing and have halted in front of the first French fortification which put up some opposition,” he complained to his diary.

Coming down the Mont Cenis Pass, the Italians had found the fort of La Turra and instead of storming it passed what there would be of the war shelling it. The newest Italian artillery was still a decade old, and the remainder of their guns and shells had been obtained as reparations from the Austrians in World War I. Eventually, the 1,000 shells fired at La Turra either just pathetically puffed against the steel and concrete walls or bounced off.

A very different artillery duel was taking place between the French in their fort at Brianconnais and the Italians inside theirs at Chamberton, which were within sight of each other across the border. The Italians did better than they did against La Turra, sometimes chipping the walls, but the French with their 280mm guns needed just 101 shells to knock every Italian gun out of action.

During earlier months of uneasy peace, French and Italian patrols fraternized along the border, the French offering chocolate and cigarettes—and buying weapons. “For every rifle they paid 5,000 lire, for a submachine gun 10,000 lire, for a machine gun 20,000 lire,” Pattoglio recalled. The easy going persisted in sectors of the front, luckily for Dutto. “In a defile the French fire from all sides. They didn’t want to hit us. If they did, it would have been a massacre.”

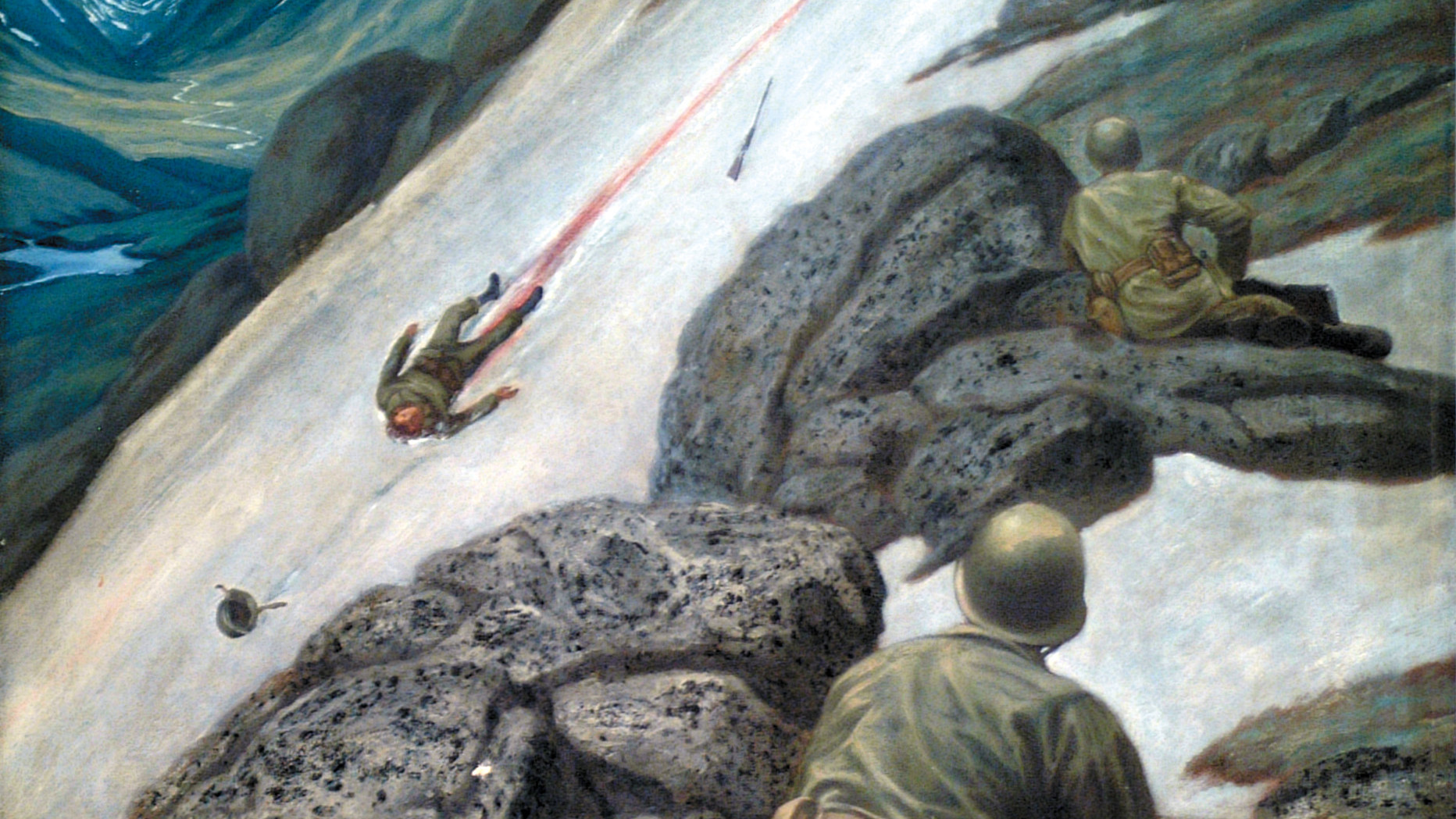

But some French were not so merciful. Lieutenant Bulle spotted a half dozen Italians protected by an icy overhang—or so they thought. Bulle had himself lowered by rope to surprise and mow down the Italians with a burst of submachine-gun fire, sending them tumbling over into the darkness.

By the end of the first day, the French were holding the Italians in the Bellcombe, Clapier, and Sollier passes while in the south the Italians’ advances were only to the La Tulle Dam and village of Abries. Mussolini knew just who to blame. “A people who for sixteen centuries have been an anvil,” he told Ciano, “cannot become a hammer within a few years.”

As bad as Mussolini’s morale was, the troops’ was worse—with far more justification. “I have first degree frostbite in my feet,” complained Giovanni Bosio of the Val Maira Battalion. “In my unit there are a lot of frostbite victims, not less than 20 percent.” It turned out the soles of their new boots were just thick cardboard. “We sleep in a kind of fortification where water collects knee-deep,” artilleryman Giovan Battista recollected.

“We have almost no ammunition,” Dutto complained. The troops were, grimly, shorter of something else. “Three days we go without eating,” lamented Bosio. “We’re always hungry, provisions never arrive,” Giovanni Raineri, 11th Battery, Fourth Alpino Artillery Regiment, echoed.

What did raise hope was news that the French had sued for an armistice. “So I put a clip into my machine gun and fire into the French valley below,” Pattoglio remembered. “All the riflemen of the Eighteenth follow my lead and start firing.

“Straight down behind us, at the base of a sheer drop of 500 meters, is deployed an infantry support division. They call our positions from the infantry headquarters, then send up messengers. Our reply is still the same: ‘Firing with joy because of the armistice.’ So the infantry division starts firing too and keeps firing its ‘shots of joy’ for three hours.”

But Pattoglio and the Italians found their celebration was premature. “Early in the afternoon,” he recalled, “unexpectedly, there’s a hail of French bombs overhead, high-caliber artillery shells. So we head for the mountains practically at a run to set up a new defense line.

“We stay two or three days on Gipiera Pass waiting for orders in the open. Snowing, farther down a sea of fog. Soaked to the bone. For shelter we dig deep holes in the snow. Frostbite.”

With the air force grounded by weather and targets too small to pinpoint from the sky, the combat burden fell on the freezing, hungry infantry. “Our infantry had to advance in the open against well-protected troops through a field under French fire,” one Italian general recollected.

One hapless lieutenant was unable to get the men under his command to fire on a French fort, and he was left futilely firing a machine gun at it by himself. The Arriesta Division needed three whole days to capture the Chennaillet redoubt on the Col de Mont Genevre—defended by just 19 French soldiers with no more than a pair of machine guns. The Pont St. Louis on the Gorniche road had even fewer holding it—a sub-lieutenant and nine enlisted men—yet it was still holding out when the war ended.

While in the north the Italians had moved barely two miles, in the south they had, such as it was, their farthest advance of five miles to the evacuated town of Menton, 15 miles northeast of Marseilles.

Ordered by Mussolini to “press home the attack regardless of losses,” the Cosseria, Modena, and Livorni Divisions overwhelmed Menton’s defenders by sheer weight of numbers and captured 60 percent of the town. But then the Italians came under a deluge of French fire from 772 guns of the 15th Corps blazing away from their position at Cap-Martin.

Then, the war, as much as it had been, abruptly ended, not on the glorious battlefield but inside a Roman villa veiled in secrecy.

The French negotiators of the humiliating armistice with Hitler flew straight to Rome to carry out the same odious chore with Mussolini. Instead of the staged spectacle they had to endure before the world at Compiegne, they were met without ceremony at the airport, to be driven by side streets to a villa blocks from the government ministries. “The meeting will take place almost secretly,” commented Ciano. But French feelings were not being spared. Mussolini “is bitter because he wanted to reach the armistice after a victory.”

The first session began that same evening at 7:30, lasting just 30 minutes, with Ciano and Badoglio presenting the terms. Mussolini’s grand territorial ambitions had been reduced to all of the ruins of Menton and a dozen Alpine hamlets—all that the Italians had managed to occupy—along with a 30-mile demilitarized zone into France until that final, formal peace conference Mussolini had hoped to buy his seat of power with the sacrifice of a few thousand fellow countrymen’s lives.

The final session started at 3:40 the next afternoon, Badoglio conducting it alone at his request, and was held up by the French refusing to hand over political refugees to Mussolini. A phone call from Badoglio to the Duce settled the issue, his sole concession, and the armistice was signed, to go into in effect in five hours, at 12:35 am, June 25, 1940.

Instead of triumph, though, Ciano confessed trepidation to his diary. “At Constantinople,” he recorded worriedly, “all the French merchant ships raised the English flag. The war is not yet over, rather it is beginning now. We are going to have so many surprises that we shall not wish for more.”

Guiseppe Demaria from the Dronero Battalion got the news when he heard the French shouting, “Italians, Italians, peace, peace.” He and his companions were finally able to make it inside the French fortifications—as invited guests.

“We had stale biscuits; the French had fresh biscuits,” he would recall. “They shake our hands, keep shouting ‘Peace, peace.’ They gave me a container of fresh biscuits, and for me the war ends like that.”

It ended on a grimmer note for Captain Lamberti. “The night of the armistice the last furious French salvos literally cleave in two the Alpino Levi, a short blond fellow in his early twenties. I still hear the fainter, ever more distant echo of his cry.”

Mussolini finally arrived at the French front five days later. Seeing a French flag over what was supposed to be Italian territory now, he was told the defenders of La Turra were refusing to come out to surrender and be disarmed.

Mussolini pondered in silence a minute. Then he ordered that they be permitted to exit, rifles at their shoulders, tricolor at their head, and be saluted as they marched back to France.

But if Mussolini could show a moment’s magnanimity he could also be delusional as well. “As I looked into their joyful, fatigued faces,” he told Ciano about the troops, “I swore then that I would have a military we could be proud of once more, no matter what the cost in career officers!”

Still, Battista Pecolo suffered in the Dronero Battalion. “If we had to fight twenty days all or at least half of us would have given ourselves up,” he said years later. “We had only one wish,” said Pattoglio, “to go home.”

“Everything seems finished; the war seems won,” said Captain Lamberti. “But the reality is bitter. Our men can only rely on their youth and their daring in painful contrast to the frightful deficiencies and recklessness of our commanders, to the unbelievable inadequacy of our weapons and our vehicles.”

The disillusionment ran to the very top. “[Party Secretary, Chief of Staff of Fascist Militia Achille] Starace , returning from the front, says that the attack on the Alps has proved the total lack of preparation in our Army, an absolute lack of offensive means, and complete lack of capacity in the higher officers,” Ciano noted with concern to his diary. “If the war in Libya and Ethiopia is conducted in the same way, the future is going to hold many bitter disappointments for us.”

There would be more than “disappointments.” Ahead was dissolution of the empire in Ethiopia, defeat in Libya, debacle in Greece. Yet worse was to come—devastation in the sub-zero snowfields of slaughter in Russia, 95,000 dead or missing. Captain Guiseppe Lamberti, Giovanni Bosio, Guiseppe Demaria, Bartomelo Fruttero, and Sergeant (as he had become) Michelangelo Pattoglio were among the 60,000 marched off to Soviet captivity as far as central Asia—and among the barely 10,000 to come back in 1946.

Mussolini never got what he wanted out of the war, not even his “few thousand” dead. Officially, there were just 631 dead, though an equal number were missing, lost in the snow, or plunging like Lieutenant Bulle’s targets into oblivion.

Another 2,631 Italians were wounded, 2,151 suffering frostbite. But for Mussolini undoubtedly the worst casualty figure was the humiliating 3,878 captured by just the handful of defenders at Chennaillet, some cut off and caught in the passes, most running from the shelling of Menton into French hands. For the French, casualties were 37 dead, 42 wounded, and 150 missing.

When those peace talks Mussolini expected to sit at finally took place, they were for Italy’s unconditional surrender to the Allies in 1943. They were conducted by none other than Marshal Pietro Badoglio during his scant 45 days as Mussolini’s successor. When the Germans started surrounding Rome in response, Badoglio’s reaction was to flee into the night down the last open road out of town, convincing himself that is was not about abjectly running for his life: “Every personal consideration had to be set aside. What remained supreme were the interests only of the country.”

Galeazzo Ciano learned, fatally, what “hard masters” the Germans were. He had unwittingly assisted in his father-in-law’s downfall, voting for the party motion requesting King Victor Emmanuel III to assume his constitutional position as supreme commander of the armed forces from Mussolini—only for its use as the pretext to arrest Mussolini, abolish the Fascist regime, appoint Badoglio, and seek surrender. After the Germans rescued Mussolini and arrested Ciano, Hitler demanded Mussolini execute his son-in-law for treason.

The Fascist firing squad bungled the job, however, and a suffering Ciano had to be finished with a coup de grace. Ironically he had written in his diary that before he would ask Ribbentrop for any help, “I would rather put a bullet through my head.”

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has written for WWII History on a variety of topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments