By William Strook

“Finally at Corregidor there was only a little crowd of American soldiers and Filipino soldiers and American nurses at the beaches, with nothing at their backs but the waters of the Pacific, and the flag came down. Bataan and Corregidor became symbols, like Valley Forge.”

So wrote a Yank magazine correspondent in 1942, shortly after the Philippine Islands fell to the Japanese on May 6. Despite much hope, heroism, and heartbreak, in the end it was numbers that counted more than courage; Japan simply overpowered the brave defenders. It was a disaster unfolding in slow motion. The Japanese seemed unstoppable, unbeatable.

How did this all come about?

First, the backstory. At the outbreak of World War II, the Philippine Commonwealth was an American possession and had been since the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898. Responsibility for defending the islands fell to U.S. Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) and the fledging Philippine Army under the command of the controversial American General Douglas MacArthur.

On paper, MacArthur’s army looked strong. There were 22,000 American troops in the islands, 12,000 Filipino Scouts (who were part of the American Army), and the 1st Regular Division. There were an additional 10 Filipino reserve divisions of 7,500 men each.

Arguably the best unit was the Philippine Division comprising the American 31st Infantry Regiment and the 45th and 57th Filipino Scout Regiments. There were also two tank battalions—the 192nd and the 194th (both National Guard units)—as well as the U.S. 4th Marine Regiment, which had recently arrived from China.

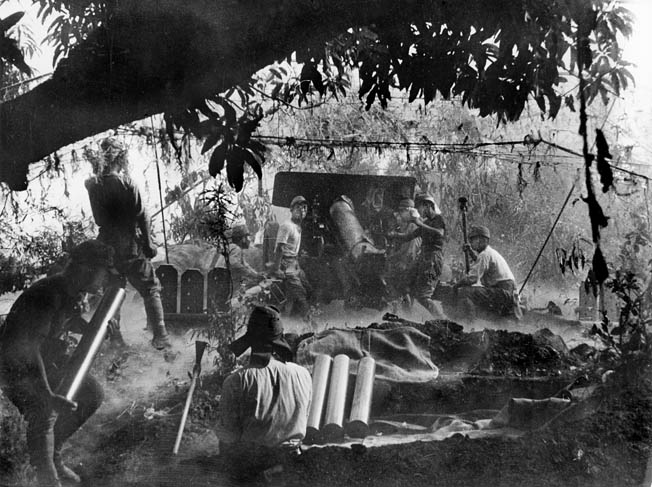

The artillery itself was old; most of the guns dated from World War I or earlier. However, the artillery officers and crews were well trained and highly motivated and during the course of the upcoming campaign would inflict severe losses on the Japanese.

The army was divided into two important formations, the North Luzon Force, consisting of four divisions under Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright IV, and the South Luzon force, two divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. George M. Parker. Another force, Maj. Gen. William Sharp’s Visayan-Mindanao Force, was composed of three divisions, almost entirely of Philippine Army soldiers. The air force defending the islands consisted of 35 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress Bombers, 107 Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighters, and scores of outdated planes spread over six Luzon airfields.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, American planners correctly assumed that the main Japanese thrust in the Philippines would be directed against Luzon. Under War Plan Orange 3, American and Filipino forces were to hold Manila and Bataan, denying the harbor to the Japanese until reinforcements arrived, which was expected to take six months. Later revisions demanded by MacArthur, under a new plan called Rainbow 5, called for him to hold the entire archipelago, harass Japanese communications, mount air raids against nearby enemy bases on Formosa and in Southeast Asia, and work with the Netherlands and Great Britain to hold off the Japanese. It was an ambitious—and totally impossible—plan.

The American units were, by and large, peacetime garrison troops while, aside from the Scouts, the Philippine troops were inadequately trained. Responsibility for the Filipinos’ poor training lay with MacArthur and his staff, who trained recruits in small camps scattered throughout the islands and then sent them home rather than forming them into battalion and regimental cadres.

If MacArthur’s training schedule was bad, his vision for defense of the islands was worse.

Upon taking command in 1935, he believed he had until 1946 to build the planned army of 12 divisions and 120,000 men. More naïvely still, MacArthur stated that an invasion could be stopped with a force of 100 bombers and 36 torpedo boats. But American and Filipino troops were poorly armed, undertrained, and led by a general who failed to understand that situation. They would pay dearly.

The Japanese force tasked with taking the Philippines was not much better. The Fourteenth Army, commanded by General Masaharu Homma, numbered just two divisions supported by one brigade and one regiment—43,000 men in all. Like the Filipinos, these troops were undertrained, poorly armed, and aging. Many were, in fact, Taiwanese.

The Fourteenth Army did enjoy strong air support and a fleet of more than 60 ships, including nine cruisers and two battleships.

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese followed up their successful raid on Pearl Harbor by hitting the Philippines. A Japanese aerial force of 108 bombers and 84 Zero fighters of the 11th Air Fleet attacked Clark and Iba Airfields on Luzon. Because MacArthur had ordered his planes to be armed and fueled for an attack on Formosa, the Japanese found the airfields jammed with B-17s and P-40s. The ensuing attack destroyed 18 of the bombers and 53 fighters and as many as 30 other aircraft. The Japanese lost only seven of their own planes to American interceptors.

The amphibious invasion began with a landing by one regiment of the 16th Division in at Aparri on the north shore and at Vigan on the northwestern coast. A halfhearted response by a half dozen B-17s and their Boeing P-26 Peashooter escorts failed to do any damage to the invasion fleet. Two days later, a brigade of the 16th Division put ashore at Legaspi, far to the south.

These were just preliminary moves meant to establish a beachhead and, if possible, draw American and Filipino forces away from the main landing beaches. But MacArthur would not be fooled and instead concentrated on mobilizing his army and getting his forces into the field.

After the Japanese ships easily sailed through a screen of 21 outdated American submarines, the invasion began in earnest on December 22. The 16th Division landed at Lamon Bay to Manila’s southeast, while the 48th Division landed at Lingayen Gulf, 100 miles to the north, a move anticipated by the Americans.

Facing the northern landing force was General Wainwright with the 11th and 71st Infantry Divisions (both Philippine Army) and the 26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scouts). The Japanese easily stormed the beaches, turned the flank of the 11th Division, and advanced inland. The first heavy fighting began later that day as the 26th Cavalry entered the town of Damortis and attempted to block the Japanese advance.

The Japanese, supported by tanks and aircraft, pushed the horse-mounted 26th Cavalry out of Damortis with heavy losses; a morning muster revealed that only 175 men were left out of more than 700. The next day the Japanese moved on Rosario, which was defended by the 71st Division. It took one concerted attack by two infantry battalions and an armored regiment supported from the air to punch through the raw Filipino troops.

On December 22, 2nd Lt. Benjamin Morin’s tank platoon of the 192nd Tank Battalion (made up of National Guard members from Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Kentucky) attacked enemy forces in the first U.S. tank engagement of World War II. With his main gun inoperable, his tank disabled and on fire, the other tanks in his platoon withdrawing, and four enemy tanks bearing down on him and his crew, Morin was forced to surrender himself and his soldiers; those who survived spent the rest of the war in captivity.

By this time MacArthur had decided to fall back to the Bataan Peninsula and ordered the Philippine Division to take up positions there. In an attempt to delay the invaders, Wainwright deployed fresh troops just north of the Agno River. From right to left they were the 21st, 11th, and 91st Divisions. From this position, Wainwright conducted a successful fighting withdrawal.

A two-pronged Japanese attack with two infantry regiments on the right with the other infantry regiment and a tank regiment on the left pushed the Filipino troops behind the Agno River. The next day saw the Japanese press Wainwright hard but, dug in behind the river, the Filipinos held for two days before withdrawing on December 27. By January 1, 1942, American and Filipino forces were concentrated in the towns of Porac and San Fernando, about 15 miles north of Bataan.

While Wainwright’s North Luzon force was conducting a successful withdrawal, the South Luzon Force, now under the command of Maj. Gen. Albert Jones, was doing the same. On December 24, the Japanese 16th Division landed at Lamon Bay, linked up with units already in Legaspi, and marched north.

These forces were opposed by the 51st Philippine Infantry Division and the 1st Philippine Regiment supported by American elements, including the 192nd Tank Battalion; Jones’s South Luzon Force fell back in good order. After the 192nd conducted a successful attack against one of the Japanese tank regiments, the South Luzon Force passed through Manila en route to Bataan.

As American and Filipino forces poured into Bataan, Wainwright fought a holding action just north of the peninsula on a line running from Borac to Guagua. His main units were the battered 11th and 21st Philippine Divisions and the remains of the 194th Tank Battalion, a National Guard outfit from California.

This line held the Japanese for a day before falling back behind a second line just south of Layac defended by the 26th Cavalry, the 31st U.S. Infantry Regiment (which had been formed in the Philippines in 1916), and the 71st Division. On January 6, the Japanese struck this line; the 31st Infantry bore the brunt of the assault and broke. Now on its own, the 26th Cavalry withdrew through the jungle, eventually reaching the safety of the main line of resistance (MLR).

The MLR ran from Abucay on the eastern coast road across the peninsula to Mauban on the west coast. In the center were Mt. Natib and the Bataan Heights. MacArthur divided the peninsula into two zones of responsibility. In the east, along a front of 10 miles, lay II Corps under Maj. Gen. George M. Parker. Parker deployed the 41st and 51st Divisions and the 57th Philippine Scouts farther inland.

On the left was I Corps under Wainwright with the 1st Regular Division (an amalgamation of police and constabulary forces) and the 31st Division defending the beaches along a front of five miles. Garrisoning the south was the 91st Division and the 2nd Regular Division (constabulary).

The island fortress of Corregidor was occupied by the 4th Marine Regiment. The position was indeed strong, but the troops defending it were tired, badly shaken, and pessimistic. Already the supply situation was dire. Brig. Gen. Charles C. Drake, MacArthur’s chief quartermaster, estimated the garrison had food for only 20 days, so the troops were immediately put on half rations.

Drake also ordered that the peninsula’s wildlife, particularly the water buffalo, be slaughtered and rice procured from local farmers. For a time, Bataan’s fishermen were hard at work supplying the defenders, but the Japanese found out and targeted their boats. The men of Bataan and Corregidor now faced starvation.

After occupying Manila, General Homma brought the balance of his forces to the borders of Bataan. Since the Japanese believed the attack on Bataan would meet little resistance, the 48th Division was withdrawn and replaced by the 65th Brigade.

On January 9, the advance began with one reinforced regiment moving down the west coast while another advanced to the east; contact was not made with American and Filipino forces until January 11. There was little action in the west, while in the east the Japanese attack fell on the 41st Division.

After a preliminary bombardment, Homma’s troops advanced across open country, where American artillery blasted the Japanese, sending them back into the jungle. The next day, the Japanese attacked along the coast, hitting the 57th Philippine Scouts. The Scouts decimated the Japanese, who again attacked in the open. One company of Scouts did temporarily lose its positions but counterattacked and retook them.

For a few brief moments, it looked like the defenders might actually stop the invaders. A Yank reporter wrote, “[Bataan] was a hot and bloody place. The Japs came down from Aparri in the north and Lingayen Gulf in the northwest. They came by the thousands, like an army of ants, and there were not enough defenders to stop them. It was like a knife through cheese, the Japs thought. Easier than China.

“Then Bataan got up and hit the Japs in the face with the old one-two, the uppercut, the right cross, the hook. The Japs got a GI kick in the teeth and a GI boot in the behind and a GI slap in the puss. That was Bataan.”

Ultimately, though, the attack was shifted back to the 41st Division and, after three days, the Filipino lines were finally breached. The Japanese attack shifted inland where it gained ground against the 51st Division. Two regiments, the 51st and 53rd Infantry, took heavy losses and were forced to give, creating a great bulge in Parker’s line.

The 51st Division counterattacked on the 16th but was unable to make any headway. Parker sent his reserve—the 31st Infantry and 45th Philippine Scouts—into the fray but, after a week of fierce fighting, they failed to dislodge the Japanese.

After absorbing the American/Filipino counterattack, Homma renewed the offensive. Two regiments pushed east while a third drove south and threatened to turn II Corps’ entire flank. As Parker’s corps began to disintegrate, MacArthur decided that the main line of resistance would be abandoned in favor of a second line about two miles to the south.

The new, shorter line ran east from Bagac to Orion. Just before the withdrawal commenced on January 22, Homma sent the 2nd Battalion of the 20th Infantry Regiment on an amphibious flanking maneuver against Bataan’s west coast. As luck would have it, the Americans captured a Japanese courier who carried detailed plans of the operation.

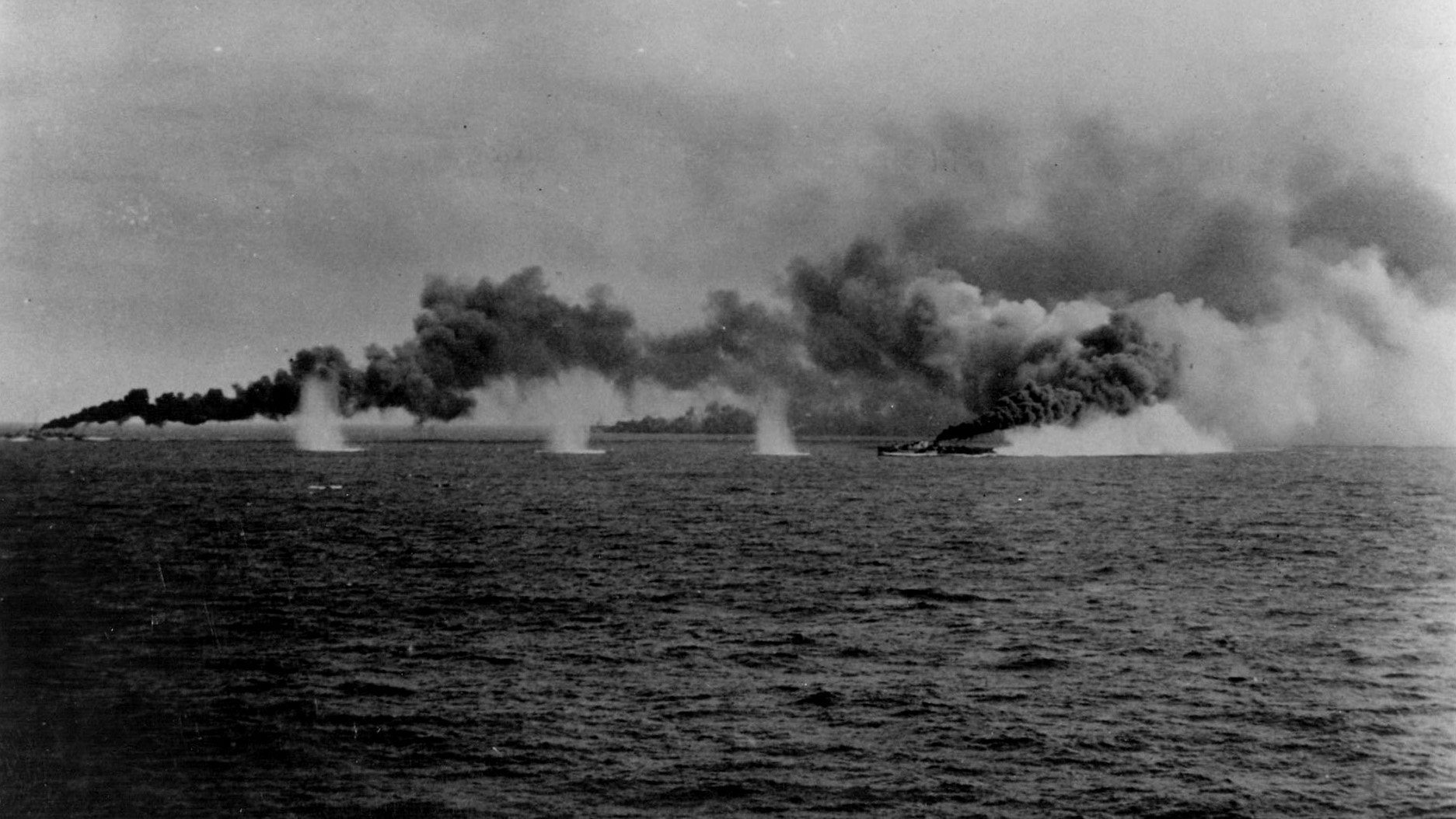

As a result, the Japanese first effort—a night landing on Caibobo Point—was intercepted and scattered by a pair of PT boats from Lieutenant John Bulkeley’s Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 3. However, several barges managed to land 600 troops below Caibobo at Quinanuan Point and another 300 men even farther south at Longoskawayan Point.

A two-week battle began during which the Japanese sent a company to reinforce Quinanuan Point. After being strafed by American P-40s, this force, too, landed at the wrong position, Anyasan Point. While all three landings were contained by improvised battalions of Air Corps and Navy personnel armed with .50-caliber machine guns scavenged from wrecked aircraft, the beachheads were not wiped out until a concerted attack was made by the 45th Philippine Scouts, 57th Philippine Scouts, and 194th Tank Battalion. Some of the Japanese on the points took refuge in nearby caves and had to be blasted out by American gunboats.

The failed amphibious attacks were launched in conjunction with a new thrust against Wainwright’s front. Initially, the drive by the remainder of the 20th Japanese Infantry Regiment met with some success and penetrated the gap between the 1st Regular and 11th Philippine Army Divisions. However, the regiment became bogged down before dogged resistance and was pulled back by the end of the first week of February.

For the moment at least, the Japanese assault had been stopped. Thinking that he had won a great victory rather than a temporary respite, MacArthur hectored his superiors for a national effort to relieve his isolated outpost. Meanwhile, Washington was desperately trying to get MacArthur to leave the Philippines to avoid giving the Japanese such a high profile prisoner and therefore a propaganda coup.

Under direct orders from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on march 15 MacArthur left for Australia, where he took command of all Allied troops.

After MacArthur’s departure, Wainwright took overall command. I Corps went to Maj. Gen. Jones while Maj. Gen. Edward King replaced Parker as head of II Corps.

Despite American and Filipino successes in January and February, the situation was dire. American bases in the Philippines were almost totally isolated. Even if the Imperial Japanese Navy could be swept aside, the troops necessary to relieve the Philippines were simply not yet available.

Worse, the army was running out of food; many soldiers were living on 1,000 calories a day. And the men in the trenches suffered from any number of tropical maladies for which the supply of medicine had been exhausted.

While the American and Filipino forces on Bataan withered, Homma replacements for his 16th Division (7,000 men), the better part of the 4th Infantry Division (11,000 men), the Nagano Detachment of the 21st Infantry Division (4,000 men), several batteries of heavy artillery, and 60 bombers based at captured Clark Airfield.

Homma then planned a two-pronged offensive with the 65th Brigade hitting I Corps and the 4th Infantry Division advancing on II Corps. The 16th Infantry Division would follow behind to exploit the expected breakthrough.

The offensive began on April 3, 1942, with a massive artillery barrage supported by bombers, which set ablaze the jungle before the American/Filipino lines. In the center of the II Corps line, the 41st Division collapsed before the onslaught. The Japanese drove south into the southern end of the peninsula and attacked up the sloped of Mt. Samat.

In an attempt to stem the tide, the Philippine Division was split between the two corps with the 45th Infantry staying with I Corps and the 31st Infantry going to support II Corps; the 26th Cavalry remained in reserve. This move could not stop the Japanese, though, who continued to fight their way through disheartened Filipino troops up Mt. Samat and down the reverse slope.

On the 5th, Homma attempted another amphibious landing, this time on the east coast below Lamao. The Americans had one last success. The landing was met by a pair of gunboats that caught the landing barges as they were drifting to shore and sank them.

On the 6th, Wainwright, acting on orders from MacArthur in Australia, ordered II Corps to counterattack and retake Mt. Samat. The halfhearted offensive was easily beaten back by the Japanese and led to the final disintegration of most of the Filipino units, save the Scouts who, with the 31st Infantry, formed a makeshift line way down the peninsula at Cabcaban.

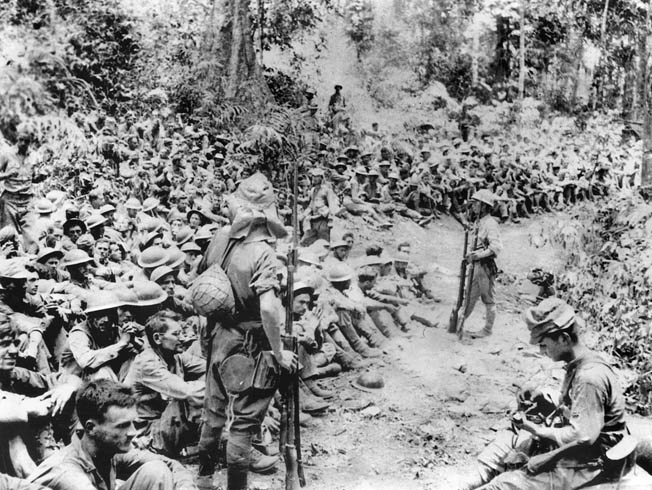

Finally, on April 9, with all hope gone, General King took it upon himself to surrender American forces on Bataan.

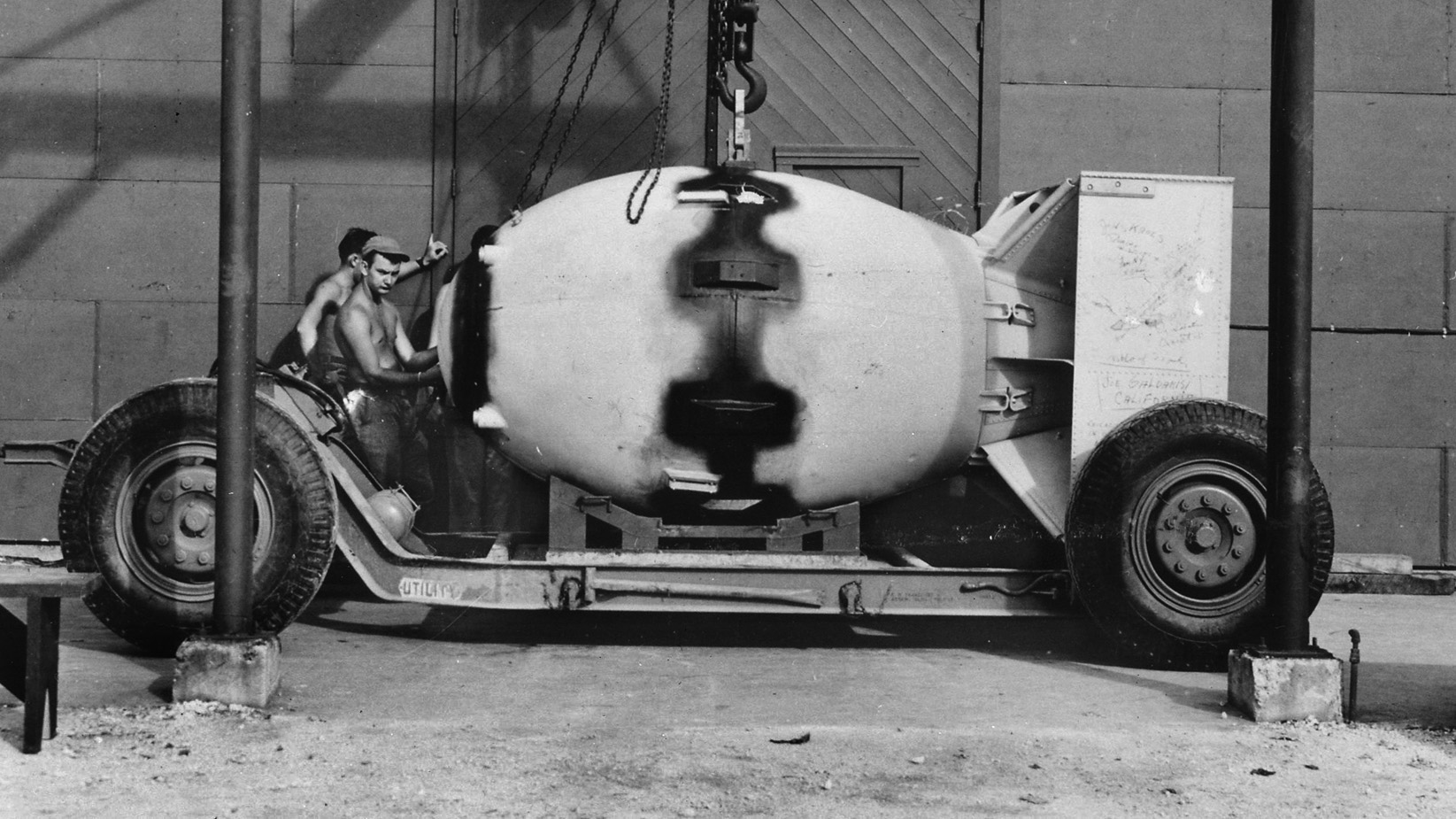

Homma now set about the task of taking Corregidor, known as “the Rock.” He assembled more than 150 artillery batteries at Bataan and across Manila Bay at Cavite, and with these guns pounded the Rock’s defenders unmercifully.

Conceivably, Homma could have starved Corregidor into submission. But Japanese forces had triumphed throughout Asia, at Singapore, at Hong Kong, at Java Sea, and Homma had lost considerable “face” during the long battle for Bataan. A successful storming of Corregidor would rescue his reputation and, it was hoped, be a severe psychological blow to the people of the Philippines.

Besides, how tough could the defenders be after months of siege, minimal rations, and ceaseless bombardment? The Japanese air force, naval assets, and Bataan-based artillery had all combined to pound Corregidor; the above-ground installations known as the Topside and Bottomside Barracks, the Navy fuel depot, and the officers club were blasted into ruins. Wainwright and the headquarters for USAFFE, the Philippine government, and a 1,000-bed hospital had all taken refuge in the island’s Malinta Tunnel.

So, rather than starve the defenders Homma planned an amphibious assault led by the 61st Regiment of the 4th Division. On the evening of May 5, American spotters saw the Japanese assembling boats at Mariveles and directed the big coastal guns of Corregidor and Fort Drum to fire on them. Tides then took the landing boats carrying the 61st Infantry Regiment 1,000 yards away from where they were supposed to land and washed them ashore between Cavalry Point and North Point.

Here they were met by Company A of the 4th Marines, which was supported by a pair of 75mm guns that blasted many of the boats out of the water as Marine machine gunners raked the beach.

The Japanese, showing considerable élan and bravery, weathered the cauldron and overran the beach. They quickly stormed across the island to Monkey Point and swept over the defenses to East Point. By 2 am on May 6, the Japanese had driven west and captured Battery Denver, which overlooked the entrance to the Malinta Tunnel and Water Tank Hill.

The battle for Corregidor hinged on the fighting here, but the outcome was never in doubt. The Marines, and then an ad hoc battalion of Navy and Air Corps personnel, counterattacked the hill despite withering fire from the Japanese, who had taken the high ground at Battery Denver. The desperate fighting lasted until late morning when, fearing what would happen when the Japanese inevitably fought their way inside the crowded Malinta Tunnel, General Wainwright contacted the Japanese to discuss surrender terms.

When Wainwright discussed surrender terms with General Homma, the latter refused to stop the fighting on Corregidor unless the U.S. commander surrendered all American and Filipino troops in the islands.

Fearing such a demand, Wainwright had released the commander of American forces on Mindanao from his authority and thus claimed that he couldn’t surrender those troops. Homma was unconvinced and reiterated his previous demand. Fearing for the lives of the 11,000 troops on Corregidor, including the 1,000 sick and wounded in the Malinta Tunnel hospital, Wainwright conceded and ordered all troops in the islands to surrender. He radioed President Roosevelt, saying, “There is a limit of human endurance, and that point has long been passed.”

Major General William Sharp’s Visayan-Mindanao Force was forced to surrender without having played a role in the campaign. Many of his men, however, escaped into the hinterland to fight as guerrillas.

Some commanders simply refused to lay down their arms. Units still operating in northern Luzon filtered into the jungle where they carried on as guerrillas. On Panay, Colonel Albert F. Christie at first simply refused to surrender, dragging the process out several days. When he finally did formally surrender, most of his troops had fled to the hills.

On Leyte and Samar, too, only a fraction of American and Filipino troops surrendered, the rest choosing guerrilla war instead or simply going home. Five infantry battalions were stationed on the island of Negros, and they refused to comply with orders to surrender, though their commander eventually managed to deliver about half to the Japanese.

General MacArthur did many great things during World War II: the New Guinea campaign, the liberation of the Philippines, his masterful statesmanship when administering Japan. But his actions in the Philippines are indefensible.

From the moment he took command, he mismanaged the training of the Filipino army by trying to forge an American-style field force to defend an island archipelago split by hundreds of languages and dialects.

Critics have said that MacArthur should have trained the Philippine Army to fight as highly mobile, semi-independent battalions that, upon a Japanese landing, would march to the sound of the guns, hold and harass the enemy. Only when the enemy had been bloodied and slowed would a main force, the Philippine Division, for example, be moved in for pitched battle.

Unfortunately, on the first day of the war MacArthur badly mishandled his air force, allowing invaluable B-17s and still useful P-40s to be caught on the tarmac by Japanese raiders. Instead of pinning his hopes on a single air raid against Formosa, MacArthur should have sent his B-17s south to Del Monte and employed them only when the Japanese fleet entered the archipelago.

Interestingly, his ideas for the defense of the waterways between the islands––a fleet of PT boats supported by fighters and bombers—were sound so long as they were backed up by gunboats and fast frigates. This was exactly the kind of force that disrupted General Homma’s amphibious landings on Bataan.

The fighting retreat to Bataan was well executed, as was the actual defense of the peninsula. However, the credit must go to General Wainwright, who deftly managed a series of phased withdrawals from Lingayen Gulf, held open the door to the peninsula, and turned back the initial Japanese assault.

MacArthur is rightly criticized for staying in the Malinta Tunnel during the battle, but his biggest mistake was keeping the 4th Marines on Corregidor. This well-trained and veteran unit could have been used as a force reserve on Bataan.

In fact, during the February lull in the fighting, the 4th Marines could have been used to deadly effect in a series of local counterattacks against the tired Japanese. General Homma later testified that a concerted counterattack would not only have destroyed his army, but could even have liberated Manila as well.

While such an operation ultimately would have been futile, it does illustrate the overall weakness of Japanese forces and show that a counterattack by the 4th Marines could have been devastating. But hindsight is always perfect.

The campaign was relatively costly for both sides, who lost a nearly equal number of men. Wainwright, who would be imprisoned in Formosa and Manchuria for the remainder of the war, lost approximately 800 killed, 1,000 wounded, and 11,000 captured; Japanese losses numbered 900 killed and 1,200 wounded. Many of Wainwright’s men were taken to prison camps around the Philippines, while others were used as slave laborers throughout the Japanese Empire.

The Philippines remained under Japanese control until 1945. A few hours after his troops landed on the shores of Leyte on October 20, 1944, to begin the Allied campaign of liberation, General MacArthur waded ashore and made a radio broadcast in which he declared, “People of the Philippines, I have returned!”

In January 1945, American forces invaded the main Philippine island of Luzon, and in February Japanese forces at Bataan were cut off and Corregidor was retaken. The capital of Manila was liberated after hard fighting in March; in June MacArthur announced that his offensive operations to liberate the Philippines were at an end.

In truth, though, nothing could have saved the Philippines in 1942. The archipelago was a lonely outpost close to Japan and far from the United States. The thousands of American troops and their Filipino allies were doomed from the start.

Very good history. Learned a lot.

Thanks for the article, it’s the best evaluation of MacArthur’s actions at the beginning of the War that I have read and I have read many. In the early days of the War, the Australians and the people of America needed to believe in someone, so the myth was created.

My late uncle (Phil Scout) once said that when MacArthur was Army Chief of Staff (early 30’s) he planned on bringing 20k US troops to the Phil which was cancelled by Roosevelt and Marshall, among other things, because of the war clouds in Europe (Europe First policy)That would have been more than sufficient to repel an invasion force even without an air force.

A marine once told my uncle while in Corregidor ” I don’t know why we’re on guard duty here, we could be fighting in Bataan….we sure have a score to settle with them Japs “(I think he was referring to their China experience) He later would die at Monkey Point in Corregidor.

Visiting Corregidor last October, while at the ruins of the movie theater, my guide asked me, guess what movie was played here for the last time for the men and women of Corregidor? Gone With The Wind. As he said that, (now we’re facing the flagpole and the parade grounds) a cool and soothing breeze came upon us, a gentle affirmation to me that their gallantry and enduring sacrifice for their Flag, their Country and their God were not in vain.

Macarthur also made the mistake of leaving behind a vast supply of rice at Cabanatuan, and rare for him, admitted it.

My father-in-law, Herminio Abilla, was in the Philippine Scouts on Mindanao. Their commander told them that before the surrender order went into effect, they were free to leave. He and some other men obtained a boat and sailed for their home island of Negros, where they joined the guerillas.

While all the Filipino troops, regulars and guerillas, were part of USAFFE and therefore US veterans, they got very little recognition after the war. The one VA clinic in Manila closed down after a few years, and they were left out of the GI Bill of Rights.

A relative in the Philippine Air Force told me a little piece of history. Flying woefully obsolete and outclassed Boeing P-26 Peashooters, the PAAF managed to shoot down one Japanese bomber and three Zeroes, before the Japanese advance forced them to burn their planes.

My late wife’s family were internal refugees on Mindanao during the war. The Filipino guerrillas looked after them as there were not so many Japanese as on Luzon and the Visayas. Very few American troops made it that far south. There had been no plans for US forces to make a fighting retreat to the South and MacArthur had no real strategy for the country as a whole despite being aware months before that they were likely to be an early Japanese target.

Biggest MacArthur screwup – not completely stocking Bataan and Corregidor with every bean, drop of gasoline, and bullet possible as soon as the news of Pearl Harbor came out. He waited too long, then prioritized stocking Corregidor. A great deal of badly-needed supplies were lost in that fashion.