By David A. Norris

Pikes and most similar pole weapons disappeared from European armies by the early 1700s. After all, bayonets let each man convert his flintlock into a pike that fired bullets. Nonetheless, 18th-century officers and sergeants still carried archaic-looking bladed weapons attached to six-foot-long shafts that seemed more appropriate to the Middle Ages than the Age of Enlightenment.

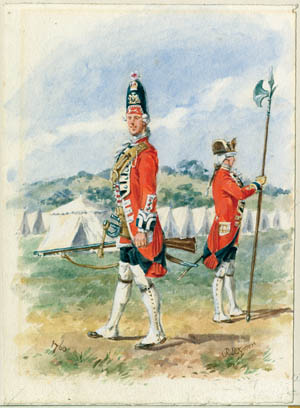

Halberds and spontoons represented military rank just as much as epaulets, gold braid, or other insignia, with the additional benefit of serving as emergency weapons in dire situations.

Halberds appeared by the late Middle Ages. The halberd’s origin, or its evolution from earlier battle axes, is obscure. Some Georgian-era antiquarians traced the weapon all the way back to the ancient Amazons of classical mythology. Other sources called it “the Danish axe” and credited its invention to the Vikings. In documented history, Swiss soldiers fighting for the independence of their cantons or as international mercenaries made the halberd famous in the 14th century.

Halberds were mounted on sturdy poles about six feet long, which were crafted from ash or similar hardwoods. The iron head had a pointed spear tip with two additional blades set at right angles to the central axis. One of these side blades resembled a hatchet head, and the other was a sharp, downturned fluke or hook. The hatchet blades often were small and crescent-shaped and could have elaborate contours and pierced decoration. On the other hand, some halberds had a monstrously large axe added to one side. Those designed for combat were usually sturdy and simple, while those with the more elaborate patterns were carried by honor guards and palace sentries.

The halberd’s pointed tip fended off opponents, as would a simple pike. The sharp point could puncture chain mail or slip between plates of armor. The curved fluke could catch a horse’s reins or pull riders down from their mounts. By swinging the six-foot-long wooden handle, the axe blade landed with considerable power on the armor of a dismounted knight. Halberdiers were vulnerable when swinging their weapons back to deal a blow. They were also at a disadvantage against soldiers carrying much longer weapons, such as lances or full pikes. In practice, armies mixed halberdiers with soldiers bearing pikes, bows, and other weapons.

Halberds also helped soldiers climb up steep slopes or defensive obstacles. The sharp axe-like blades were also handy for hacking and tearing down field fortifications such as fascines or gabions.

Deploying their formidable infantry with a mixture of halberds and pikes, the united Swiss cantons during the 14th and 15th centuries defeated several Burgundian and Hapsburg armies. In 1386, Duke Leopold of Austria and many of his troops were killed by the halberd when the Swiss routed the Hapsburg army at the Battle of Sempach. At the 1477 Battle of Nancy, the halberd-wielding Swiss destroyed the army of Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy. The duke was killed, his head split by a halberd. This catastrophic defeat finished Burgundy as a major power, and its lands were absorbed by the Hapsburgs and the French.

European monarchs, well aware of the effectiveness of Swiss troops, hired Swiss mercenaries and also adopted the halberd for their own armies. In 1480, Louis XI of France founded a mercenary company, le cent-Suisses (The Hundred Swiss). Armed with halberds, they served as a palace guard as well as accompanying French kings on military campaigns.

In 2012, the remains of King Richard III of England were exhumed from beneath a parking lot. Extensive forensic examination of the royal skeleton found evidence of multiple wounds evidently sustained at the 1485 Battle of Bosworth Field, where the king was slain. Scientific analysis indicated that it was quite likely that Richard III’s fatal wound was inflicted by a halberd.

Halberds came to the Americas in the early 1500s, with Spanish conquistadors such as Cortez and Pizarro. English colonists brought halberds, which they often spelled as “halbert,” to Jamestown and New England, and Dutch soldiers carried them in New Amsterdam. Jamestown’s laws of 1612 required sergeants to bear halberds during garrison duty but carry firearms in the field. There is evidence of their use during the 1636-1638 Pequot War in New England. Generally, in the Atlantic colonies halberds were carried by honor guards or militia sergeants rather than combat troops. Accounts of Indians using halberds may refer to a small hybrid “halberd tomahawk.”

The heyday of the halberd ended in the early 1500s. Swiss troops, who were heavily dependent on the halberd, were decimated by French artillery at Marignano in 1515. A Swiss army hired by the French met a similar fate at La Bicocca in 1523, their halberds and pikes no match for Spanish infantry armed with the arquebus. In 1525, the Hundred Swiss were killed to the last man in a vain attempt to save Francis I from capture at the Battle of Pavia.

Fading as a battlefield weapon, the halberd stayed in military usage as a symbol of a sergeant’s rank. Gervase Markham wrote in 1625 that in England “halberds doe properly belong to the serjeants of companies.” For two centuries, halberds were closely associated with sergeants in European armies. Havildars, the equivalents of sergeants in the Indian companies of the army of the British East India Company, also carried them. Expressions such as “to get a halberd” meant receiving promotion to sergeant. By the late 17th century, if an English sergeant was demoted his dishonor was intensified by the confiscation of his halberd in front of the assembled company or garrison.

Sergeants straightened their formations, set distances between the ranks, or prodded men into line with the halberd. François-Apolline de Guibert wrote of the Prussian Army in 1778, “The sergeants’ halberds are sixteen feet long …. The divisions are closed at the right and left by sergeants; who, when there is occasion, hook their halberds together, and by this means enclose their platoons, so that the soldier cannot make his escape, but is obliged to fight.”

Because they could serve as measuring rods, halberds were useful for surveying the layout of a new camp. In a more macabre function, halberds were used to drag the dead from the ranks during a battle.

Some armies allowed sergeants to strike soldiers with the staffs of their halberds. For more formal punishment, sergeants tied halberds together to form makeshift whipping posts. Often, three were placed together as a tripod, while the prisoner was lashed to the staff of a fourth halberd tied horizontally across two of the other ones. In the British Army in the 18th century, to be “brought to the halberds” meant to get a flogging.

Sergeants of British grenadier and light infantry companies carried fusils instead of halberds. But, in battalion companies, sergeants carried halberds until 1792. In that year, sergeants took up pikes or spontoons.

One of the first weapons ever captured by American troops was a halberd. On July 1, 1775, a party from the new Continental Army made a predawn raid on the British lines outside Boston Neck. Driving away some redcoats, the patriots set fire to a guard house and carried off some spoils of war: two firearms, one drum, and one halberd. However, halberds otherwise are little mentioned during the American Revolutionary War. While spontoons found use among the Continentals, the British while fighting in America put aside their halberds, and the Americans never officially made use of them.

Even today, a few special units of European soldiers are equipped with halberds. When the Swiss Guard of the Vatican was founded in 1506, such weapons were standard issue for foot soldiers. Members of the same unit, attired in Renaissance-style uniforms, still carry halberds today. Other modern halberd bearers include Spain’s Royal Guards and two British units: the famed Yeomen Warders (i.e., Beefeaters) who are posted at the Tower of London, and the Yeomen of the Guard, who serve as royal bodyguards and ceremonially open Parliament.

The French still use an expression, “Il pleut des hallebardes” (it’s raining halberds), in the way English speakers might say, “It’s raining cats and dogs.”

Spontoons (also spelled “espontoons”) appeared later than halberds, coming into use in the late 17th century. The word seems to come from the Italian spuntone, meaning “pointed.” A spontoon’s iron point, sometimes decorated with tassels, was fitted to a sturdy hardwood shaft measuring from six to nine feet in length. The weapon’s distinguishing feature was a sort of crossbar, sometimes plain and sometimes elaborately ornamental, perpendicular to the main blade.

Spontoons may have evolved from earlier spear-like weapons called pertuisanes or partisans. The partisan had a large blade, sharp on both sides. The blade was wider at the bottom, where twin symmetrical blades of various shapes sprouted from the sides. Rather blurry lines separate the spontoon and a number of other spear-like staff weapons. There were hybrids known as “partisan spontoons,” and some 18th-century European accounts refer to officers’ weapons as partisans rather than spontoons. Other sources refer to spontoons as “half-pikes,” and some simply call them spears.

Never primarily intended for combat, the spontoon was introduced to armies as a new symbol of officer rank. They appeared in France in 1690, with new military regulations requiring infantry officers to carry an espontoon. After 1710, junior officers carried fusils instead, but senior officers retained their spontoons until the French Army abandoned them in 1756.

Following the French example, the infantry officers of Spain carried spontoons between 1704 and 1768. Many foot officers of Great Britain, Prussia, Austria, Russia, and other European countries also used them, although in some armies officers of grenadier regiments carried fusils instead of spontoons.

In drill formation, officers saluted with their spontoons, and they could also convey orders with them. Standing one vertically on the ground indicated a halt. Tilting the point forward signaled a forward movement; tilting it backward ordered a withdrawal.

Although ornamental, spontoons nonetheless were deadly weapons. Numerous accounts mention their use at the Battle of Culloden in 1745. Captain Lord Robert Kerr of Barrell’s Regiment (4th Foot) speared a charging highlander with his spontoon before he was cut down and slain moments later.

By some accounts, Kerr died because he drove his spontoon so deeply into his enemy’s body that he was unable to draw it out before he was attacked again. By the late 1800s, British tradition had it that the spontoon’s crosspiece was added as a result of Kerr’s death. However, an April 1746 account of the battle in The Scots’ Magazine explained that a spontoon is “a weapon used of late years by the officers of foot.” According to this article, even before the Battle of Culloden the spontoon was already “rendered more fit … by a cross-stop, which makes it easily recovered, when thrust into the enemy; whereas the half-pike usually run so far, as to be lost or broken in those occasions.”

Also at Culloden, Lt. Col. George Howard of the 3rd Foot slew the Jacobite officer William Drummond, the Viscount of Strathallan, with his spontoon. A postbattle report stated that among the heavily involved redcoat regiments, “there was scarcely a soldier or officer … who did not kill one or two men with their bayonets and spontoons.”

In America’s wilderness, many professional officers saw long pole or staff weapons as useless impediments. Before his ill-fated 1755 march that ended in the disastrous defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela, Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock ordered his sergeants and officers to leave their spontoons and halberds behind.

In 1786, British Army regulations decreed that “the Espontoon shall be laid aside,” and that officers would thereafter “make use of swords.” Even before that, during the Revolutionary War many British officers never carried them in combat. In March 1776, the sergeants and officers of the First Guards were ordered to stop carrying halberds or spontoons. These orders were for safety as well as practicality. “A report being current that the Americans were in the habit of picking off the officers,” discarding their pole arms would “assimilate their appearance more to that of the men.”

Halberd-carrying British sergeants exchanged their traditional weapons for a spontoon or half-pike in 1792. Thus, these staff weapons appear in accounts of battles in the Napoleonic Wars.

At the Battle of Corunna fought on January 16, 1809, Major Charles Napier commanded the 50th Regiment. In front of a chest-high wall, his men halted under heavy French fire. Some men crossed at a lower section of the wall, but the rest still hesitated. “Leaping back,” wrote Napier, “I took a halbert, and, holding it horizontally, pushed many over the low part.” A Sergeant Keene followed Napier with his own pike. Four of five of the enemy aimed their muskets at the British major, but Keene spoiled their aim by striking their musket barrels. When Napier’s men formed a new line in front of the wall, he laid his “halbert … over the men’s firelocks to keep their level low.”

Sergeant’s pikes or halberts were at the center of desperate clashes over regimental flags and French eagle standards. At the Battle of Barrosa on March 5, 1811, Sergeant Patrick Masterson of the 87th Regiment of Foot used his pike to kill a standard bearer of the French 8th Regiment of the Line. Masterson captured the first Napoleonic eagle taken during the Peninsular War. At Salamanca on July 22, 1812, two French eagles were taken. One, seized by the 44th Regiment, had been detached in vain from its staff by a French soldier trying to hide it from capture. The British fastened their prize to a sergeant’s “halbert” and held it aloft on its new staff.

At the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, Lieutenant R.T. Belcher of the 32nd Regiment of Foot picked up the regimental colors when the regiment’s ensign was wounded. Nearby, a French officer had his horse shot from under him. The Frenchman charged Belcher and grabbed the staff, but the British lieutenant managed to grasp the silk cloth of the flag. In a moment, the French officer started to draw his saber. Before he could get the sword from his scabbard, a color sergeant of the 32nd named Switzer impaled the Frenchman with his halbert.

In the armies of Russia and some German states, the spontoon survived into the first decade of the 19th century. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the British Army did away with the sergeant’s pike in 1830.

Although the British serving in America put aside their pole weapons during the Revolutionary War, spontoons formed part of the equipment of the Continental Army. Captain Daniel Morgan led a portion of the Continental attack on Quebec on December 30, 1775. His men carried spontoons in addition to rifles and scaling ladders. Attacking a two-gun battery, they drove the defenders into a nearby house. Morgan ordered his men to “fire into the house and follow up with their pikes (for in addition to our rifles, we were also armed with long espontoons), which they did, and drove the guard into the street.”

In several surviving written orders, General George Washington insisted that Continental officers carry spontoons. At Valley Forge on December 22, 1777, Washington directed that each officer “provide himself with a half-pike or spear, as soon as possible.” Washington did not want his officers to carry muskets, which he believed had a way of “drawing their attention too much from the men.” He needed the officers focused on commanding their men, not distracted with loading and firing a musket. Additionally, Washington believed that an officer with neither firearm nor spontoon had “a very awkward and unofficerlike appearance.”

In America, spontoons held on into the early Federal period. A North Carolina militia law of 1787 required infantry officers to carry “side arms or a spontoon.” Because militia officers might well wear civilian clothing, a spontoon or sword served as an indication of superior rank.

The U.S. War Department ordered 120 spontoons for its officers in 1800. Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark each carried one during their transcontinental expedition of 1804-1806. Both officers would have reason to be glad they were burdened with these heavy staff weapons. In what is now Montana, on the night of May 26, 1805, Lewis nearly stepped on a rattlesnake. Guided by the sound of the rattles, Lewis stabbed about in the dark with his spontoon until he killed the snake. Three days later, Clark killed a wolf with his spontoon. Lewis’s spontoon would twice more save his life, once in driving away a bear and another time when the captain saved himself from falling 90 feet from a precipice by bracing himself with his weapon’s long staff.

Lewis and Clark may have been the last American military officers to get any real use out of the spontoon. Watchmen and policemen in some cities carried smaller versions of spontoons until about 1860, but by the time of the War of 1812, they had essentially disappeared from military life. However, William T. Sherman, in an 1890 article in the North American Review, pointed out that U.S. militia laws still on the books stated that “each commissioned officer shall be armed with a sword or hanger and spontoon.” So, strictly speaking, all militia officers without spontoons were in violation of Federal statutes until the militia laws were revised in 1903.

I confused ‘spitoon’ with ‘spontoon’ haha

As an American Revolution reenactor years ago, going “up the ranks” from private to officer meant exchanging the musket for a spontoon. It was definitely the corrrect implement for an officer, easily recognized by the soldiers and not being a distraction by having to load, fire and maintain after battle (no cleanup of a smelly fouled firearm reaquired – I am well acquainted with that!). Before that, as a French and Indian war “sergeant” I carried the halberd. Same comments as above. Thanks for another informative article.