By Robert E. Cray, Jr.

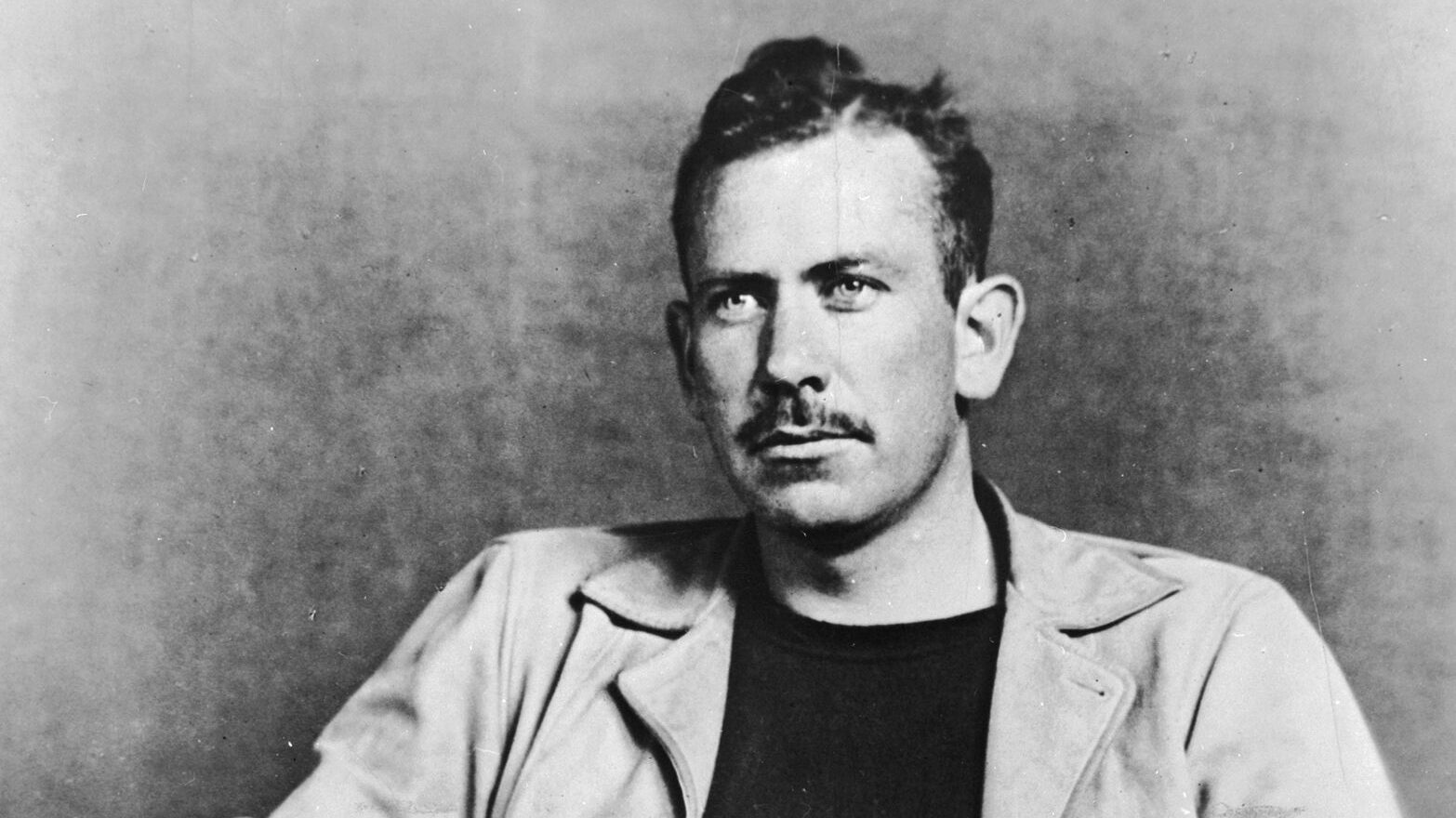

A fuming John Steinbeck vented his frustration over World War II to a friend on March 15, 1943. Employed by the government in home front duties, the Pulitzer Price-winning author of The Grapes of Wrath expected a big military push to come soon, and he wanted to be overseas, not stateside, covering the war.

As an accredited journalist, Steinbeck could still write and yet be in the thick of the fighting. But his temper flared as he told his friend, “From what I have so far, if I go into the army I would prefer to be a private. The rest is very like the fraternity system at Stanford. I have not been notified of rejection by the way.”

He would get his wish and more, participating in the Salerno invasion and serving alongside a special commando unit that would enable him to blur the role of journalist and soldier.

John Steinbeck Working with the Military: Crossing the Line Between Author & Journalist

With the U.S. entry into World War II in 1941, Steinbeck agreed to write about a bomber crew, using his literary talent to craft a training manual for the Army Air Forces. Steinbeck attended class with the crew, flew in planes alongside the airmen, and learned about bombing and gunnery. Bombs Away: Story of a Bomber Team represented a patriotic ode to brave men and flying machines. Steinbeck had crossed the barrier between literary author and observant journalist. Nevertheless, he refused to compromise standards, deliberately missing deadlines to ensure quality work.

World War II journalists were a varied bunch with a strong sense of professional identity. Reflecting upon war correspondents in the late 1950s, Steinbeck described them as a mixture of the “curious, crazy, and yet responsible.” He should have added nasty. Some members of the fourth estate clearly resented Steinbeck’s intrusion on their turf.

John Steinbeck never named names, but on one occasion several boozed up and boisterous correspondents told Steinbeck in no uncertain terms that his work stunk. It was the ultimate insult. That Steinbeck collected royalties from best sellers and enjoyed big payouts from movie adaptations of his novels spurred his new colleagues’ jealously. They had toiled professionally for years, met deadlines, and polished their craft. Now Steinbeck came barreling along trying, they thought, to upstage them.

Popular With Families Back Home

Newly credentialed correspondent Steinbeck observed his surroundings closely, traveled aboard troop ships, probed England’s war-battered society, and developed a poignant story line. Little things—the troopships crammed with men’s boots, the tail gunner frantically searching for his good luck medal, or the sergeant noticing an English country cottage illuminated without blackout curtains that later turned out to be a bombed-out ruin, for instance—provided his takeaways.

Steinbeck made seemingly ordinary things resonate. His stories, newsmen eventually realized, did not compete with theirs, easing the tension, and they sometimes assisted the neophyte with on-the-job advice. The public lapped up Steinbeck’s stories. British newspapers picked up his stories, as did almost every state back home except Oklahoma, still fuming over his depiction of the Dust Bowl migrants. Even South American papers ran Steinbeck’s column.

Steinbeck understood the dangers of going to the front. He took heart from what Robert Capa, his closest journalist friend and a noted war photographer, had told him: “Stay where you are. If they haven’t hit you, then they haven’t seen you.” But what if one broke the rules and fought alongside the troops? Then the odds against mounted.

Earning Battle Stripes With Douglas Fairbanks

He would come to earn his battle stripes with the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy in 1943. In England and later in North Africa, Steinbeck had been a step removed from the battlefront. Not so with this invasion.

Despite the Italian government’s surrender by September 1943, the Germans tenaciously resisted. In preparing for the invasion of Italy, Steinbeck managed to assign himself to a secretive special operations unit based on British commando units. Its purpose was to deceive the enemy, launch sudden raids, and disrupt communications; fast mobile torpedo boats would riddle enemy shipping. British, American, and Dutch ships offered support. The unit’s commander, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., a Hollywood movie star turned commando leader, redefined the meaning of swashbuckler, trading screen props for ordnance.

Steinbeck was drawn to the charming, charismatic Fairbanks. Little wonder; Fairbanks not only told a good story, borrowing from his actor friend David Niven’s seemingly endless repertoire of entertaining and off-color anecdotes, but also amused onlookers with impersonations of Charlie Chaplin and Errol Flynn. Beneath the glib exterior, Fairbanks was all business. His recruits, drawn from military bases and college campuses, won assignment for their expertise in electronics, demolitions, and gunnery, not for their sense of humor.

Deception & Integration

Deception figured highly in the unit’s operations. By getting the Germans to believe the special operations force was part of a bigger unit, Fairbanks and his team hoped to tie down enemy forces away from the main action. Whether using torpedo boats or making surprise landings, the commandos planned to confuse and disorient the Germans. In this, they achieved results. Later accounts indicated that an entire German division had been duped into believing that the main invasion of Italy would occur north of Naples rather than at Salerno, according to Steinbeck biographer Jackson J. Benson.

The commando unit continued to launch raids up and down the coast after the initial invasion. Steinbeck dutifully filed his stories. However, his particular vantage point during such raids went unstated because Steinbeck had in effect become a commando himself. Correspondents, identified by their insignia, could follow troops into battle. But Steinbeck tore off his badge, tailed along with the raiders, and cradled a machine gun that the commandos had thoughtfully provided. An admiring Fairbanks recalled that Steinbeck’s gesture had won the men’s respect. If captured by the Germans alongside the commandos, Steinbeck could easily have been shot.

No evidence exists that Steinbeck fired his weapon or killed anyone during the war. Yet, he appreciated professionals at work who might have done so. That included men with a certain flair beyond what even actor Fairbanks could summon.

“I’ve done the things I had to do”

John Steinbeck experienced deadly combat during the Salerno landings. It was a nasty operation, both loud and bloody. In fact, Steinbeck’s eardrums burst from the explosions. Any doubts Steinbeck had about his own courage quickly ended. The writer saw death firsthand, viewed corpses, and watched bullets and ordnance fly. Then he wrote his stories back aboard the command ship, which drew enemy fire as bombs and alerts went off every half hour. It was a harrowing experience that the sensitive Steinbeck long remembered. When writing to his wife on September 20, 1943, he offered an explanation and rationale for what he had seen “because I’ve done the things I had to do, and I don’t think any inner compulsion will make me do them again.”

John Steinbeck experienced deadly combat during the Salerno landings. It was a nasty operation, both loud and bloody. In fact, Steinbeck’s eardrums burst from the explosions. Any doubts Steinbeck had about his own courage quickly ended. The writer saw death firsthand, viewed corpses, and watched bullets and ordnance fly. Then he wrote his stories back aboard the command ship, which drew enemy fire as bombs and alerts went off every half hour. It was a harrowing experience that the sensitive Steinbeck long remembered. When writing to his wife on September 20, 1943, he offered an explanation and rationale for what he had seen “because I’ve done the things I had to do, and I don’t think any inner compulsion will make me do them again.”

After the war, Steinbeck chose to keep certain memories close to him so as not to forget. He routinely wore a British naval officer’s hat proudly emblazoned with the royal lion and unicorn. On a 1960 trip across the United States that led to the book Travels with Charley, Steinbeck donned the hat while near the Atlantic or Pacific coast. It was his way of remembering World War II and to pay homage to men lost. (Read about other notable figures who participated in the Second World War inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Originally Published September 17, 2014

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments