By Mark Simmon

After successfully fighting seasickness during the crossing of the English Channel, Lance-Corporal Ted Brooks of Number 48 (Royal Marine) Commando arrived on Nan Red Beach—which formed the left flank of Juno Beach—on the morning of June 6, 1944. He had, for much of that time, avoided feeling “queasy” by lying on his back—that is, until he stood up to get ready to land. This was his first time in action, but he felt “apprehensive” rather than afraid.

“It was obviously very noisy during the approach,” he remembered, “but one thing that stuck in my mind was the silence on the landing craft just as we went in.”

That silence was broken by a burst of machine-gun fire when Brooks’s landing craft was still a few hundred yards from the beach. Ted recalled, “One man shouted with an indignant tone in his voice, ‘Who the f…..g hell’s firing?’” This appealed to the Commandos’ black humor and somehow relieved the tension. Ted felt it was “so funny at the time.”

The Commandos of Operation Neptune

Ted and his mates were taking part in the most momentous event in the history of combined operations. This was the day, since the dark days of 1940, that all the training and previous operations had been leading to. Theirs was a crucial mission, for without securing the beaches, the great mass of the Allied armies behind them could not begin their drive through France and into the heart of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

Over 16,000 Royal Marines—less than 10 percent of the entire invasion force—were about to participate in Operation Neptune, the assault phase of Operation Overlord, the largest combined aerial/amphibious operation in history. Most of the landing craft were manned by Royal Marines and all capital ships (battleships and cruisers) carried RM detachments. Five RM Commandos, grouped with three Army Commandos into two Special Service Brigade units, were scheduled to be landed during the assault phase. In addition, the Royal Marines provided a number of specialist units, including an armored support group, beach clearance and control parties, and engineers.

The Allied armies taking part in the Normandy invasion were under the overall command of American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, while the ground commander was British General Sir Bernard Law Montgomery. The plan for the invasion had been drawn up by General Sir Frederick Morgan, chief of staff to the Allied supreme commander.

Early on, Morgan had proposed that the landing should take place on a narrow front with three divisions, for he felt constricted by the limited amount of landing craft available. However, to have a chance of success, Montgomery believed that the amphibious landing should be expanded to five divisions and several Commando units. Three Army Commandos (Numbers 3, 4, and 6) and five Royal Marine Commandos (Numbers 41, 45, 46, 47, and 48) in two brigades would be landed.

The Commandos had a variety of tasks to perform, but broadly they fell into two main categories. Initially, they were to take and hold the flanks of the main beaches, allowing other troops to move inland unhindered. Then, with their light equipment and ability to move swiftly, they would support the airborne troops landing behind enemy lines.

Training the 48 Commando

The men of 48 Commando were part of No. 4 (Special Service) Brigade commanded by Royal Marine Brigadier B.W. “Jumbo” Leicester, along with 41, 46, and 47 Commandos. Formed in the spring of 1944 largely from 7th Battalion Royal Marines, 48 Commando was rooted in a unit that had a checkered history. It had been raised in 1941 and sent to South Africa to perform guard duties. It was not in fact needed there and thus was left idle in Durban. By 1943, it had moved on to Egypt.

Later it took part in the Sicily landings (Operation Husky), where it fought against the crack Hermann Göring Division. It reached the Italian mainland (Operation Avalanche) but was soon ordered home to England to reform as a Commando. There it had a stroke of good luck to have Lt. Col. James Moulton appointed as its commanding officer; he took command in March 1944.

Moulton was told he could have his pick of men from the 7th Battalion and from the Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisation II. Not all the men for the Commando came from these units; some were seagoing marines from ships of the fleet. All should have been volunteers, but such was not always the case.

Tony Pratt was “selected,” as he explains, after having joined the Royal Naval Air Service when he was 17. “After one Sunday church parade,” he said, “we were all lined up and asked for volunteers to join the Royal Marine Commandos. I thought this would be even worse and, of course, did not volunteer. The sergeant came along the ranks with his stick and began saying, ‘You, you, and you’ and passed me by.” Pratt thought he was safe but the sergeant came back, pointed at him, and said, “And you,” which is how he got into the Commandos.

All the men went to Achnacarry in Scotland’s chilly, windswept western highlands for Commando training. Located on the grounds of Achnacarry Castle, the historic seat of the Clan Cameron in the Lochaher region, the Commando Training Center usually ran a six-week course that was reduced to an intensive 18 days for 48 Commando. Colonel Moulton recalled that they went through “the usual torments.” The camp commandant, Colonel Charles Vaughan, had welcomed them, telling them the instructors were the best around and, “They will not ask you to do anything that they cannot do themselves.”

Sergeant Joe Stringer discovered that the trainees lived in the field, even though it was winter and they were “permanently cold, wet, and tired.” Many of them had already experienced active service, but it made no difference to the instructors. Any of the men could ask at any time to be released and returned to his unit, but none ever did. At the end of training the men were awarded the coveted green beret.

The Atlantic Wall

Four hundred men started the course, and they finished it together emerging as 48 (Royal Marine) Commando. In early April 1944, 48 Commando moved to Gravesend in Kent, where the unit continued training with battle drills, field exercises, physical conditioning, speed marches, and assault courses. Ten days were spent on the rifle ranges at Sheerness honing their marksmanship. On May 20, secret orders arrived that told them that they would be taking part in the long-awaited liberation of France and Europe. Their objective was to land on a beach code-named Juno, near Nan Red, at the beach resort town of St.-Aubin-sur-Mer.

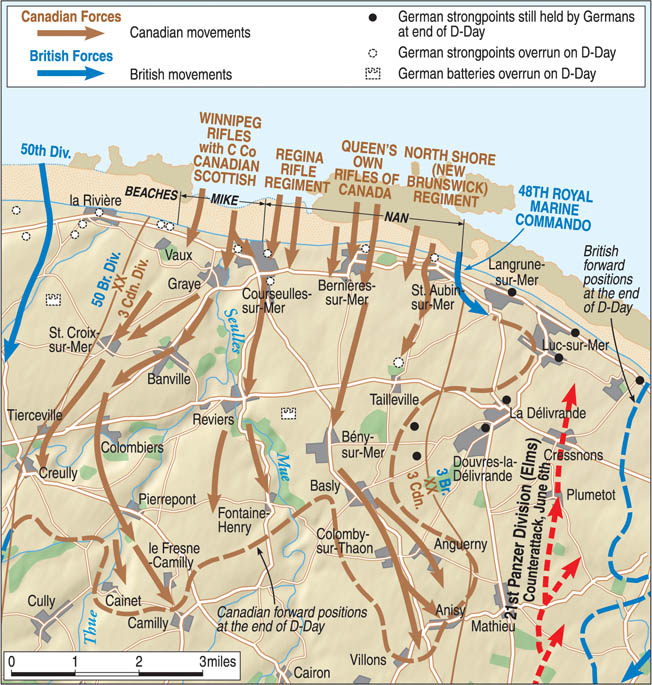

They would come in behind the Canadian North Shore Infantry Regiment, which was supported by the tanks of the Fort Garry Horse, 35 minutes later. Then 48 Commando would pass through the Canadian beachhead, moving east toward Langrune and taking the beach defenses from the rear before linking up with 41 Commando. That unit would be landing on Sword Beach on the right flank and would move west toward Langrune, thus linking Juno and Sword Beaches.

The Germans did not know when or where the invasion would come, so Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, in charge of Army Group B, did everything possible to fortify the likely places along the coast. He had his own men, conscripted civilians, and slave laborers brought in for the job, working to exhaustion to make the French coast impervious to invasion. The workers built thousands of reinforced concrete bunkers and gun emplacements, flooded some open fields and studded others with a forest of poles to discourage glider landings, carpeted the beaches and areas inland with millions of mines, and placed fiendish obstacles along the shoreline to obstruct, impale, and destroy landing craft.

Tens of thousands of German soldiers stood guard all along the coast, which Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels had called “the Atlantic Wall,” touting it as being impregnable. The area where 48 Commando was scheduled to land was guarded by the 736th Regiment, 716th Division, backed up by mobile units of the 21st Panzer Division.

Weathering the Storm in LCIs

After the invasion was delayed for 24 hours due to a fierce storm raging through the English Channel, 48 Commando embarked at Warsash, Hampshire, on June 5 and sailed for France.

Moulton’s 48 Commando was transported across the Channel in LCIs, Landing Craft, Infantry (small), operated by the 202nd Flotilla from the support craft HMS Tormentor at Warsash. The LCIs were 104 feet long with a speed of 11 knots and could carry 96 fully laden troops along with a crew of 17. These craft had the advantage of eliminating transfers from larger ships to smaller assault craft, but that was about their only advantage. Sea-keeping qualities were poor, and the LCIs were constantly rolling even in moderate seas. Made of plywood, they provided little protection from enemy fire. The engines ran on high-octane fuel from unprotected fuel tanks.

Colonel Peter Young, commanding officer of No. 3 Army Commando, described the crossing in an LCI: “The storm which had already delayed us for 24 hours had not yet abated. All through the night our small craft pitched and rolled. I found it impossible to sleep; most of us were seasick, flung about by the crazy pitching of our craft; it was a miserable night. Breakfast for me was just a mug of cocoa, which went straight over the side, but otherwise I was not unwell.”

Colonel Moulton felt that LCIs were the wrong craft as they were “designed for back-up infantry, not as assault craft…. You landed by gang-planks over the bow, quite useless for heavily equipped men in rough water.”

As the Commandos approached the beach, they swapped their helmets for their coveted green berets. To soften up the enemy, a tremendous aerial and naval bombardment of the coast commenced at dawn on D-Day.

“An enormous weight of bombs and shells was delivered in the space of a few hours,” said Colonel Young. “It was a crucial phase of the operation and, of course, a tremendous encouragement to the men in the landing craft as they ran in, head-on, to sample whatever the West Wall might have in store for them.”

“Intelligence Was Poor”

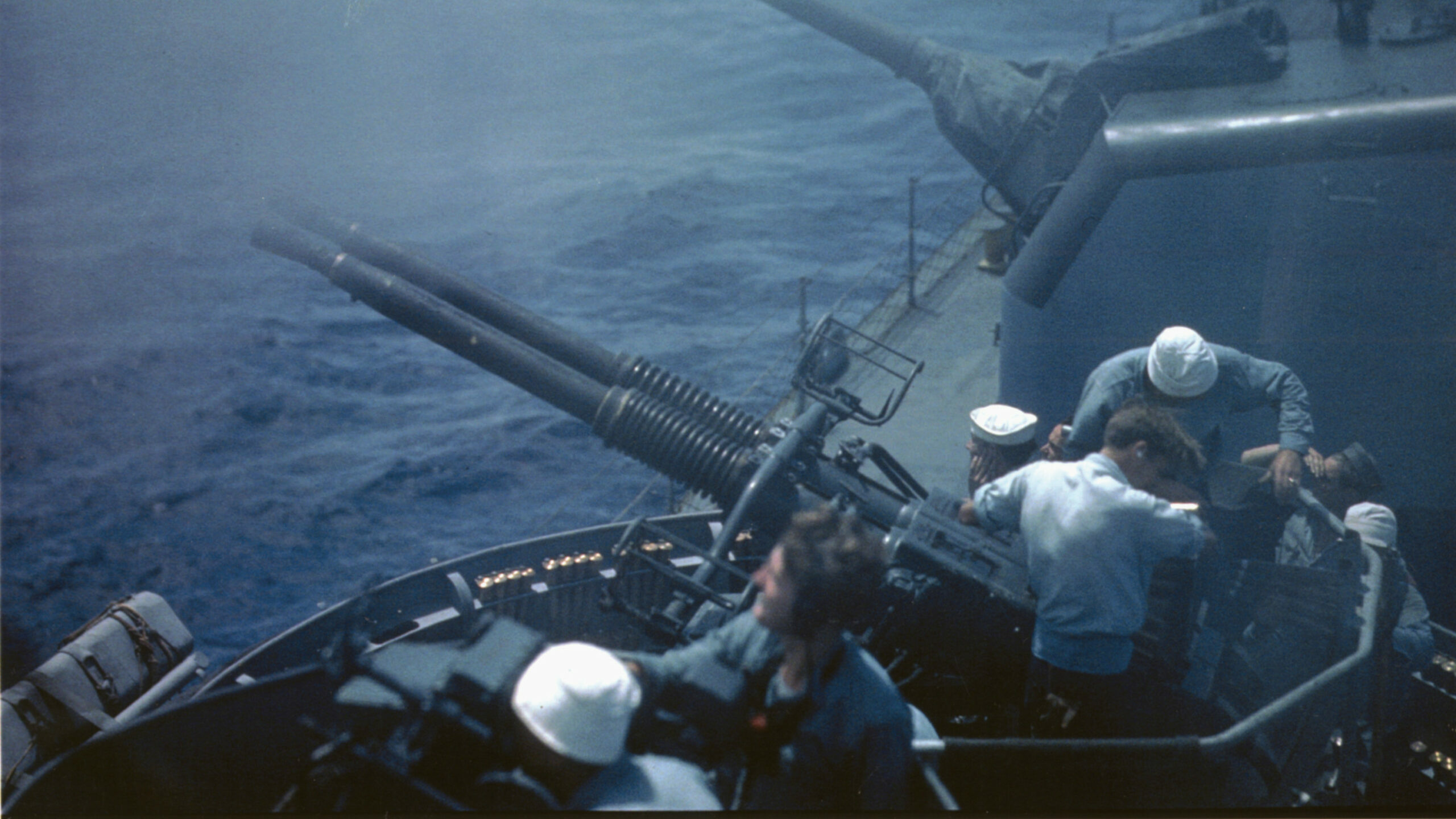

What the West Wall had in store for them was a strong, well-organized defense. At first, though, as the unit’s official report stated, “It appeared that the landing would be unopposed and most craft dismounted the 2-inch mortars which were prepared to cover the landings with smoke. Then machine guns opened up from the strongpoint at St.-Aubin, which was almost opposite the easternmost landing craft and perhaps 2,000 yards from the westernmost, and the craft were subjected to mortar and shell fire; the Z Troop craft received a direct hit amidships [killing six men]. The Oerlikons [20mm automatic cannon normally used aboard ships as antiaircraft weapons] replied and the craft put down smoke on the beach, with 2-inch mortars.”

Colonel Moulton had the foresight to train his men to fire 2-inch mortar smoke from the bows of the craft during the run-in to the beach. The smoke screen hid the craft from direct fire, but beach obstacles and shrapnel holed the wooden hulls, killing and wounding troops and crews.

“Intelligence was poor,” said Moulton. “We were told of a continuous line of fortifications along the shore, but it wasn’t like that. The Germans built concrete strongpoints in the villages, and we landed right in front of one.”

Harry Timmins recalled the approach on board his craft carrying A Troop: “As we got nearer the beach, the noise was more than you could possibly imagine. There were explosions all around us in the sea and the shells and mortars were kicking up sand all over the beach. A couple of buildings were on fire and, to add to the tumult, the Oerlikon guns on our boat also joined in the barrage and deafened us.”

Confusion on the Beach

Most craft did not beach square on the waterline, exposing troops trying to scramble down the bow gangways that were constantly moving in the swell. Many marines were pitched into the sea to wade ashore in waist-deep water, while others were thrown in headfirst and were swept away by the fast-flowing current and drowned.

Captain Geoff Linnell, commander of the Heavy Weapons Troop, witnessed a desperate scene: “The ramps were too light for the ends to sink to the sea-bed; they floated about in the surf. As each man tried to come down them, the footway beneath him heaved alarmingly with each incoming wave. Many men were thrown completely off the sides and floundered in the water, dragged down by their heavy packs. When I got down the ramp, there was a big sea and a great undertow that nearly took my legs away.

“Some men with inflatable lifebelts up around their chests had been knocked over by the swell and were floating away upside down with their legs in the air, drowning as we watched.”

The official report said, “On reaching the shore, troops made for the cover of the earth cliff and sea wall. Here they found a confused situation. The cliff and sea wall gave some protection from small-arms fire, but any movement away from them was under machine-gun fire. The whole area meanwhile was under heavy mortar and shellfire. Under the sea wall was a jumble of men from other units including many wounded and dead; the beach was congested with tanks, self-propelled guns and other vehicles, some out of action, others attempting to move from the beach in the very confused space between the water’s edge and the sea wall. LCTs were arriving all the time and attempted to land their loads, adding to the general confusion.”

Confusion reigned on the beach for quite a while. Major Derick de Stacpoole was wounded before he left his craft but managed to make it to shore; Captain Frederick Lennard, a strong swimmer, drowned in the rough surf. Lieutenant Louis Fouche was already on the beach with orders to direct men along to the right as they came ashore, but he was hit almost immediately by mortar fragments and seriously wounded; his orderly was killed. The landing of Y Troop was slow, and a few men managed to get ashore before the LCT shoved off, taking with her about 50 men of the Commando back to England, despite their energetic protests. Some jumped into the sea in an attempt to join their unit, but many who did drowned in the surf.

“Four-Eight Royal Marine Commando—This Way”

Dougie Gray of B Troop made his way up the beach to the sea wall, picking his way through the bodies of Canadian soldiers that had fallen during the first assault. The wall provided some cover from small-arms fire but not much from mortars: “The Germans in the strongpoint at St.-Aubin had our range and bearings, and the mortar bombs came over in regular waves. One bomb landed right among us and I was hit by a piece of shrapnel in my back. I found it hard going when I moved down the wall to try and get off the beach; my wound was slowing me down.”

Gray was later picked up by Canadian medics and taken to one of their aid posts. After 48 hours he was shipped back to England and was operated on at the Canadian hospital in Basingstoke to remove the shrapnel from his back.

Harry Timmins was surprised to see Colonel Moulton walking on the beach “steadily and steadfastly, bolt upright, despite the shells and mortars dropping all around, and the ping, ping, ping of the bullets whizzing by. He stopped, looked around and, at the top of his voice, cried out, ‘Four-Eight Royal Marine Commando—this way,’ pointing along the beach. Everyone within earshot got up and followed him.”

While Colonel Moulton was trying to rally his men, a mortar bomb landed close by, blowing him off his feet. At first he thought he had a broken leg, but on closer examination he saw he had been hit by bomb splinters in the hand and leg. Shrugging off his injuries, he was quickly on his feet and directing his men to the assembly area inland where he found much of his force was missing.

Jock Mathieson, a Headquarters Troop member, got off the beach and made it to the assembly area where he waited with others in a ditch close to the coast road. He said that in the ditch there “was the body of a young French boy no more than about eight years old. It looked as though he had been killed by blast, probably during the preliminary bombardment. The sight shook me up considerably.”

Ted Brooks said that in the assembly area the group came under fire from a sniper in the tower of St.-Aubin church. However, a disabled Canadian tank came to their assistance and “obligingly put several rounds into the tower” and silenced the sniper.

Once Moulton felt he had gathered as many men as possible, he had a roll call that told him he had lost about a third of his men. Lieutenant Harold Smedley then returned with a situation report from the North Shore regimental headquarters.

Advance on WN 26

After hearing the report, Moulton decided it was time to advance on nearby Langrune, although it would leave his left flank open as the Canadian infantry was still trying to take St.-Aubin and the German strongpoints overlooking Nan Red Beach. However, he was sure, now that tanks were assisting the Canadians, it was only a matter of time before that position would fall.

Moulton now decided to split his force in half. He sent B and X Troops along the coast road toward Langrune’s seafront, while he took the remainder of the unit, with A Troop leading inland, toward the church of Langrune, 600 yards from the sea. Once there he would hold the village from counterattack. After B and X Troops had cleared the coastal area, the reunited Commando would move against the strongpoint known as Wiederstandsnest 26, or WN 26.

Sergeant Joe Stringer was with B Troop as it started its advance but soon suffered from a “friendly fire” incident. He noted that the second-in-command was cut down by a burst of “Orelikon fire coming from one of the warships off the beach.” They had to leave the officer there; the gunfire had also killed another marine and wounded two others.

However, the Commandos and Canadians had broken through the outer defenses of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall and were moving inland to allotted objectives. Hundreds of Germans had been taken prisoner and would be sent to England on LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank).

As the Canadian North Shore Regiment was still trying to take WN 27 at St.-Aubin-sur-Mer, the marines of 48 Commando moved against WN 26, covering the eastern end of Nan Red Beach and connected to the streets and buildings with trenches and wire entanglements. The stretch of coastline between the two strongpoints was lightly held, but the 2,000 yards between them was covered by interconnecting fire.

B and X Troops were advancing along the road behind the coastline, but the closer they got to Langrune the heavier the enemy fire became and WN 26 was still under fire from supporting warships. Ralph Dye, a member of the Forward Observer Bombardment Group, recalled they ranged in the destroyer assigned to them. “The strongpoint at Langrune was battered with accurate fire from the destroyer but showed little sign of giving up,” he recalled.

Moulton’s inland group made good progress toward the center of Langrune. It moved in open order taking advantage of any available cover. Heavier equipment was brought up in an odd variety of transport including a stroller and ice cream wagon.

Reaching the town, Moulton set up his headquarters in a walled manor house that he had already identified from aerial photographs. To the east was the church, beyond which were open fields. Sword Beach was just three miles farther east.

By now B and X Troops were closing in on strongpoint WN 26 and clearing the shoreline as they went; the Germans fell back in good order. The two Commando troops took turns taking the lead and providing covering fire. They cleared gardens and climbed over walls between houses until they began closing in on a minefield and wire entanglements marking the edge of the strongpoint. Here X Troop was forced to ground by well-entrenched enemy machine guns protected by concrete.

WN 26 consisted of a block of ordinary houses facing the seafront, all reinforced with concrete. The doors and windows were blocked up, and the buildings were surrounded by barbed wire. Covering the landward approach from the town were two machine guns.

Mortars inside the compound covered all approaches. Facing the beach were two guns—a 75mm and a 50mm housed in concrete four feet thick. Snipers occupied many of the outlying buildings.

With two of his Commando troops engaged, Moulton was ready to deploy his remaining force. Z Troop and the remains of Y Troop were ordered to defend the town against any counterattack from the south.

Moulton kept A Troop in reserve, and part of X Troop was ordered to keep the pressure on the enemy while the remainder moved against the western end of WN26; B Troop closed in from the south. Moulton then sent A Troop to follow B Troop and complete the surrounding of the German strongpoint from the landward side. Meanwhile, a party from Z Troop was ordered to make contact with Sword Beach.

Fire Support From Centaurs

About this time, two Centaur (A27L) tanks of the 1st Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment arrived at Moulton’s headquarters. After the colonel sent them down the road to help B Troop, the first Centaur approached WN 26 from the east, firing its 75mm main gun and two 7.92mm machine guns as it moved and giving cover to B Troop, which took advantage to move in closer. The tank’s fire smashed one machine gun and drove into the reinforced houses.

Colonel Moulton was up in the thick of the fighting. Marine Jock Mathieson was with him. “I was with the colonel when we went forward to survey the strongpoint,” Mathieson said. “He wanted a tank to blast the concrete wall that spanned the road ahead. He spoke to its commander through the phone on the side, but learned that the tank could not depress its gun sufficiently low enough to hit the base, so Moulton told him to keep pounding the concrete until it broke up.”

The Centaur used all its ammunition to little effect. It then pulled out, and the second tank came forward. This tank, however, was not so fortunate; it struck an antitank mine and lost a track. The crew bailed out and joined B Troop, occupying some nearby houses.

Taking WN 26

For the moment the attack was stalled. With the machine gun at the crossroads of the outer defenses destroyed, B Troop was able to get closer. However, it could not find a way into the concrete-sealed houses, and it was coming under accurate mortar fire. B Troop withdrew. Time was now running short; in a few hours darkness would descend, and losses were mounting.

Brigadier Leicester, commander of the 4th Special Service Brigade, now arrived at Langrune to confer with Moulton. He told him to call off the attack and dig in to prepare for a possible counterattack and keep the garrison of WN 26 sealed in. Reports were that the 21st Panzer Division was on the move, possibly toward Allied positions.

Thus, the longest day for 48 Commando came to a close. The unit had suffered heavy casualties.

The next day the unit succeeded in capturing WN 26 with the aid of more armored support and the use of Bangalore torpedoes—pipes packed with explosives—to blast a way in. The German defenders fought back tenaciously, but a Sherman tank physically broke into WN 26, followed by the Commandos.

Marine Jock Mathieson was one of them: “Once we were inside, many of the enemy quickly gave themselves up. I began searching the prisoners. One of them was well over six feet tall and wore an overcoat that reached down to the ground. I put my hand into one of his pockets and pulled out an English grenade. I nearly shit myself with fright, thinking he had primed it to explode.” Luckily, he hadn’t.

Thirty-one prisoners were taken at WN 26. For the next two days, 48 Commando policed Langrune and St.-Aubin and buried its dead comrades along with some Canadian dead. Lieutenant John Square was given the task. “We got a group of our men together and buried mainly men from our Commando,” he said, “but a few others who happened to be about, including Canadians who were still lying in the garden of a large house fronting the beach. The garden was supposed to be mined, but I don’t think it was. We set up a small cemetery in the garden of another house close by. We wrapped up the bodies in their gas capes and conducted a moving burial service.”

Continuing the Allied Advance

After D-Day, 48 Commando captured the German strongpoint at Langrune-sur-Mer and held it until the rest of the 4th Special Service Brigade had landed (41, 46, and 47 Commandos). The first two days of the D-Day landings had cost 48 Commando 217 dead, wounded, and missing out of a strength of around 450. Only five officers were left out of 15. But their job was not yet over; more battles lay ahead.

After receiving reinforcements on June 9, 48 Commando resumed patrolling while awaiting new orders. On June 17, the unit joined with 46 Commando to take the German Würzburg radar station at Douvres-la-Delivrande, between Juno and Sword Beaches. After knocking it out, the 4th Special Service Brigade moved on to the River Orne to join the British 6th Airborne Division in mopping-up operations.

Lieutenant D.C. “Tommy” Thomas, a South African serving with the airborne unit, recalled, “And were the paratroops glad to see us!” He further remarked that for the next few days none of them knew much of what was happening, and no one knew whether the invasion was a success.

On August 20, 48 Commando carried out two attacks on a hill near the town of Dozulé, about 15 miles east of Caen, held by elements of the German 711th Division. After these attacks were unsuccessful, the unit was reinforced by 46 and 47 Commandos and then bypassed the town and marched to Clermont-en-Auge, where the Commandos attacked German field batteries before midday. They later secured the high ground overlooking Dozulé.

Instead of being withdrawn, the 4th Special Service Brigade continued with the Allied advance to the Seine. It took part in liberating Pont l’ Evêque, Saint Maclou, Pavilly, Yerville, Motteville, Yvetot, Bermanville, and Valmont. After 84 days in action, 48 Commando came out of the line in August.

Finally, 48 Commando returned to England to rest and refit but was back in action again during Operation Infatuate in early November 1944 to help liberate the heavily fortified island of Walcheren at the mouth of Holland’s Scheldt River. Later, the unit remained in the battle in Holland, raided across the Maas River in Holland, and took part in the occupation of Germany.

In January 1946, with the war over, 48 Commando was disbanded along with all the Army Commandos and some of the Royal Marine Commandos. The men of 48 Commando had done their job to secure victory for the Allies and had done it well.

My Grandad Reg King was in 48 Commando X Troop. Proud reading this.