By Glenn Barnett

After the war in Europe was won, General Dwight D. Eisenhower had many opportunities to review various campaigns with the leaders of the Soviet Army–– including even Joseph Stalin himself.

Without exception, the Russians wanted to ask Ike one thing. “It was,” Eisenhower wrote in Crusade in Europe, “to explain the supply arrangements that enabled us to make the great sweep out of our constricted beachhead in Normandy to cover, in one rush, all of France, Belgium and Luxembourg, up to the very borders of Germany. I had to describe to them our systems of railway repairs and construction, truckage, evacuation, and supply by air. They suggested that of all the spectacular feats of the war, even including their own, the Allied success in the supply of the pursuit across France would go down in history as the most astonishing.”

The Twentieth-Century Demand For Supply

Twentieth-century warfare brought with it an urgent need to move massive amounts of supplies to far-flung battlefields around the globe. Before the mechanical age, horses and mules moved wagonloads of supplies the short distances that armies could march on foot. Horses could feed on any local hillside and drink from any stream or pool. Most often men, too, lived off the land.

Mechanization changed warfare as much as the machine gun did. Motorized vehicles carried everything from soldiers to heavy guns, requiring vast amounts of fuel, lubricants, spare parts, mechanics, and motor pools. Aircraft required ground crews, regular maintenance, and huge fields from which to operate.

The vast distances to the fronts in Europe and the Pacific required the movement of men and material from America by ship over thousands of miles of submarine-infested oceans.

When World War II began, the United States was not yet able to produce or deliver great quantities of supplies to its own armies, let alone its allies. It was an enormous frustration for the nation to watch the isolated garrisons on Wake, Bataan, and Corregidor wither on the vine and be conquered from want of supplies and reinforcements.

The Battle of the Atlantic was the first round of the supply war in Europe. It was fought to keep supplies flowing to Great Britain and the Soviet Union to sustain them while American troops added their punch against the common enemy.

The 16th Port

The Army Transportation Corps came into its own in 1942. It was an amalgamation of the railway transportation duties of the Corps of Engineers, the motor transport function of the Quartermaster Corps, and other assets that were involved in moving men and matériel. This included engineers who could build and maintain roads, bridges, railroads, harbors, and warehouses.

One unit of the Transportation Corps in the enormous chain of supply that linked the home front with the front line was known as the 16th Port, activated on May 24, 1943. Its mission was to repair, restore, and operate the ports to be used by the Allies in Europe. By early July its compliment of 409 enlisted men, 109 officers, and one warrant officer was filled, and in mid-July the 16th began a 13-week intensive course of basic training. All the officers and 91 percent of the men qualified in their rifle training.

More importantly, their training included the construction of the USS Simplicity (not to be confused with a World War I patrol boat of the same name). This was a miniature model of a Liberty ship with which the men could practice problem solving in the loading and unloading of scale-model cargo and vehicles in the most efficient manner. Later, the land ship, Gloria, a full-sized section of a real Liberty ship, was used to practice the operation of winches, cranes, forklifts, and other machinery in cargo handling.

On January 8, 1944, the 16th Port shipped out from New York harbor, but not without incident. Their transport ship, the SS Mauritania, struck a tanker while still in harbor and was compelled to return to dock. Damage was minor, and she sailed the next day for England, arriving at Liverpool on January 18 in the midst of the D-Day buildup. The 16th Port story was but one small chapter in overall Allied strategy.

Invading North Africa

Long before the activation of the 16th, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had ruled out any invasion of Europe in 1942 or 1943 in large part because of the inability to ship the goods necessary to supply an invading army. The simpler alternative of invading Vichy-held North Africa was complicated by prowling German U-boats. Almost daily the planning staff of the invasion had to reschedule transport of vital supplies when news arrived that a cargo ship had been sunk. Further, every ship that was to assist in North Africa was a ship taken away from supplying England. In the days before great numbers of Liberty ships slid down the ways, hard choices had to be made about priorities and resource allocation.

Supply was a key factor in determining the North African landing sites. Casablanca was chosen as a beachhead because it sat at the terminus of a trans-North African railroad that stretched all the way to Tunisia. When captured, the rickety railroad was only capable of hauling 900 tons a day, a small fraction of what was needed to sustain a major operation. Railway engineers of the Transportation Corps soon upped the capacity to 3,000 tons a day. This was even before American-built locomotives and freight cars could be brought over.

The initial defeat of American forces in the Battle of Kasserine Pass awakened a remarkable spirit of cooperation between the Army and Navy in astonishing ways. Eisenhower recorded that a shipment of 5,400 trucks was to go to North Africa. General Brehon Somervell, the war department supply and procurement chief, told Ike that the vehicles could be loaded onto transports in the States within three days if only the Navy, busy with its own problems, could provide convoy protection. Ike picked up the phone and called Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest Joseph King. Within a few hours, King had made the arrangements, and the trucks began arriving in North Africa three weeks after the initial request.

A humorous postscript to this affair came from one of General Somervell’s aides who coordinated the shipment from Washington. At the end of a letter detailing the horrific logistical problems involved in the shipment of the trucks, he concluded with, “If you should want the Pentagon shipped over there, please try to give us about a week’s notice.” The new trucks contributed to improving the supply situation in Tunisia.

Port Repair and Salvage

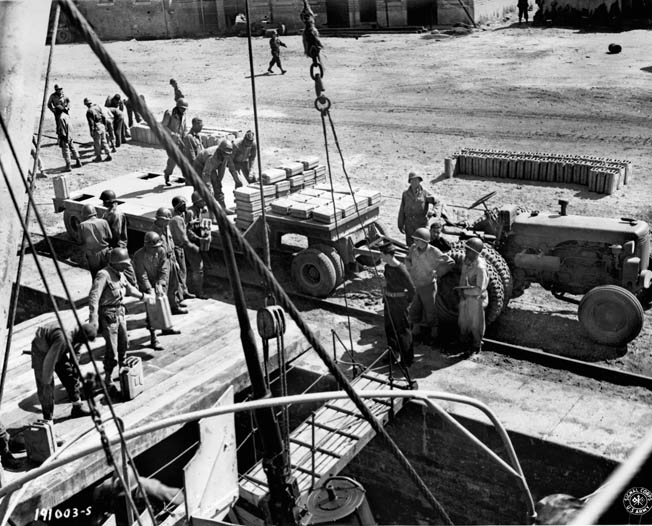

Besides moving men and material by ship, rail, and truck, the Transportation Corps was given responsibility for cleaning up captured harbors that had often been wrecked and operating them to bring in more men and material, as well as evacuating the wounded and enemy prisoners of war.

With each new campaign, the engineers and sea salvage experts of the Corps, working closely with their British counterparts and local civilian labor, gained more experience. By the time Naples was liberated, the harbors of Casablanca, Algiers, Oran, Bizerte, and Palermo had been cleared by these teams who by now knew what they were doing.

Naples was the first harbor that the Germans had an opportunity to systematically destroy before the Allies arrived. Yet, the seemingly useless mass of sunken ships, blasted docks, ruined cranes, and burned warehouses was quickly repaired and put back into service to bring in the needed fuel, ammunition, and food. As important as the Italian campaign seemed at the time, it soon became a backwater to the main event in Europe, the invasion of Normandy.

16th Port on D-Day

The 16th Port was now in the thick of it. When it landed in England in January 1944, it was immediately put to work. The outfit was temporarily divided and assigned to assist the 15th Port in Liverpool and the 17th Port in several busy Bristol Channel ports. They at once set about employing their new skills at unloading supplies and men in preparation for the invasion across the English Channel. At one point the Bristol ports handled 45 percent of all the cargo unloaded from the transatlantic convoys, and Liverpool was one of the largest and busiest ports in the world. The 16th got plenty of on-the-job training.

As D-Day approached, the 16th Port was reconstituted in the Bristol Channel area and given the new responsibility of loading supplies and vehicles onto invasion transports. The 16th’s job was twofold; while they were loading ships for Normandy, they were still unloading the growing flood of men and material coming from the States.

One unit of the 16th based in Cardiff, Wales, unloaded more than 80,000 tons of supplies during May 1944. That included the complete cargo of 25 ships and partial unloading of five more. One transport ship, the Texas, made two port visits in May loaded with locomotives and tanks. On her first trip the 16th had the Texas unloaded within 48 hours; on the second trip the heavy cargo was removed in 36 hours.

The actual invasion itself did not give the 16th any respite. The demands for supplies of all types soared. The outfit worked a seven-day week until its orders came to shove off for France to continue its work at a Normandy port. There, new problems awaited. Invasion planners long knew that the capture and use of northern European ports would be crucial to Allied victory.

General Eisenhower defined the problem: “A reinforced division consumes from 600 to 700 tons of supplies per day. In a fixed position most of this tonnage is represented in ammunition, on the march the bulk is devoted to gasoline and lubricants.”

Two artificial harbors, known as Mulberries, were prefabricated in England, towed across the Channel, and sunk in place at Allied beachheads in Normandy. These impromptu ports received men and material until June 19, when severe storms struck the Channel. For four days, winds and high seas battered the coast, destroying one of the makeshift harbors in the American sector and grounding over 300 ships and boats, some beyond repair. The American 83rd Division was compelled to ride out the storm in its battened-down troopship for nearly a week. When calm returned, the poor GIs came ashore seasick and exhausted.

Despite the delays, by July 2 there were a million Allied soldiers (23 divisions) in the narrow enclave at Normandy. In addition, 566,648 tons of supplies and 171,332 vehicles had been brought in to support the expected breakouts of the beachhead.

Meanwhile, the Allied siege against the important French port city of Cherbourg was successful, and the town fell on D-Day + 20. Cherbourg’s port facilities had to be cleared of rubble and hundreds of German mines and booby traps. It was not until July that the first supplies could be unloaded, and not until August that the port was fully operational. Cherbourg was soon woefully far behind the rapidly moving front lines.

By August 1, 1944, there were 35 active Allied divisions on the Continent; on October 1 (after Operation Dragoon, the invasion in southern France), there were 54 divisions. As the front moved rapidly, sometimes 75 miles a day, the never-ending need to transport the sheer volume of supplies was compounded by distance.

In Europe, the scattered elements of the 16th Port would be reunited and, for the first time, operate under their own command. On August 5, General William M. Hoge, commander of the 16th, and a team of five officers and six enlisted men flew to France to make arrangements for the rest of the command to follow. Landing at Cherbourg, they drove down the peninsula in the midst of some of the still-raging battles with German holdouts around St. Malo and elsewhere.

The rest of the men loaded onto LSTs for their journey to the Continent and got a taste of war on their short passage. A U-boat fired torpedoes at them, hitting one LST and sinking a small LCT that got in the way. The attack was not pressed, and the men of the 16th Port arrived at Utah Beach on August 20.

Their immediate assignment was to handle five small ports around the recently liberated St. Malo. Between the time they landed and September 22, the 16th Port and attached units unloaded 62,000 tons of gasoline, oil, ammunition, and rations. On out-going ships, they embarked 4,200 casualties for England. Some supplies (745 tons a day) were offloaded at St. Michel-en-Greve. There was no actual port there, only a beach where the tides were extreme. LSTs steamed up to the shore at high tide. As one observing Frenchman noted, they were closer to shore “than even the fish can swim.”

As the tide receded, lines of trucks rushed across the beach to the stranded ships. Cargo was manually offloaded to the waiting trucks, which then roared off with their loads to the waiting supply dumps. When the tide returned to release the beached LSTs, the trucks began hauling cargo from the dumps to the front on the dedicated roads of the famed Red Ball Express, and the LSTs lifted off to procure more supplies.

Restoring Le Havre

During this time, the important French port of Le Havre at the mouth of the Seine River was captured, and the 16th Port was reassigned to operate the facility. In peacetime, Le Havre had been an important port for commercial steamships. The French luxury liners Normandie, Ile de France, and City of Paris, as well as many others, docked there; many Americans got their first prewar glimpse of France at this bustling port city of 170,000 people.

The port included 11 major docks; half of the 218 acres of sheltered harbor could take ships drawing 23 feet of water. For the 16th Port it was no pleasure trip. Le Havre in 1944 bore little resemblance to its prewar appearance. During four years of Nazi occupation, the port had been idle due to an effective British blockade. Only small German torpedo boats and minelayers called the port home. After D-Day fast German E-boats slipped out of Le Havre at night to attack Allied convoys in the Channel. In response, the harbor and city were bombed and at least 20 enemy vessels were sunk. Mine and torpedo storage areas were also struck, increasing the damage.

As Allied forces drew near Le Havre, the Germans systematically prepared powerful demolition charges in strategic locations along the quays and docks. Mines were laid and wired electronically. The Nazis were very thorough. The official Allied estimate was that the harbor area was 100 percent destroyed and the city 70 percent destroyed (much of the damage to the city was due to Allied bombing). Only 25,000 of the civilian population still remained in the city to greet their liberators, and these were very dispirited. Many were seen wandering among the ruins searching for loved ones in the rubble.

There was little time to assess the damage; repair work had to be done quickly. The 373rd Engineer General Service Regiment had overall responsibility for clearing the port, but the 16th did its part in clearing the rubble. The unit immediately cleared two stretches of the beach of mines, barbed wire, and rubble to make room for landing craft bringing in supplies. Impromptu roads were bulldozed and obstructions cleared. Formerly fashionable French beaches turned into German defensive strongpoints were now major Allied supply mini-ports as the unloading went on day and night. The task of cleaning up was begun in late September, and the first three LSTs were unloaded on October 2.

With the beaches cleared and supplies moving rapidly ashore, the next task was to restore the ruined harbor, canals, and locks. Among the other important tasks, storage space had to be cleared for 100,000 barrels of petroleum, oil, and lubricants. Fortunately, the manpower was available.

By this time in the war, the 16th Port was a miniature army in its own right. Attached to the headquarters organization of 500 men were operating units of stevedore companies to unload ships. There were truck companies to haul supplies to depots and ordnance outfits that prepared tanks and other equipment for use. They also supervised the handling of bombs, shells, and other munitions. There were also amphibious truck companies that drove the famous and indispensable DUKWs, commonly known as Ducks, from ship to shore. Eisenhower thought the Duck was one of the most important vehicles of the war.

Of vital importance were maintenance and repair units, the heroes that restored the damaged docks or built new ones; composite medical units; military police companies; harbor craft companies to operate tug boats; and air defense batteries and radar units to guard against enemy planes and U-boats. At its peak, the 16th Port would have as many as 15,000 soldiers attached to its service, plus thousands of French civilians who were employed to perform different duties.

The key to Le Havre’s calm inner basin was the Rochemont lock and the adjoining Transatlantique lock. The gates of both locks had been damaged by the Germans. But the enemy had failed to sabotage a dry dock, thinking it useless in light of the other damage. What they had overlooked was that the gates of the nearby dry dock were still serviceable. These soon replaced those of the Rochemont lock.

The onset of bitter winter weather and accompanying storms in the Channel made the task of restoring the entrance to the inner harbor even more important. On December 16, 1944, the first Liberty ship made its way through the locks and into the safety of the inner basins.

There was a long list of other, seemingly never-ending, tasks to be done. The Seine River needed to be cleared of obstacles, and the Tancarville Canal, which joined the harbor to the river, needed repair. Floating docks were built and extended into the basin to accommodate the Liberty ships. Warehouses were constructed to provide sheltered storage space. There were also 286 miles of highway to maintain.

The Army was not alone in the restoration and repair job at Le Havre. The 628th Navy Seabee (naval construction) unit and the 1716th and 1717th Royal Marine Engineers worked in close cooperation to clear the harbor of its wreckage and construct pontoon piers.

The Success of Le Havre

One important factor always noted in the success of supply efforts was the contribution of the African American units. Segregated for the most part, these all-black outfits of stevedore and driver battalions literally carried the burden of supply. Even during the war, their indispensable labor was acknowledged by the Army at all levels.

General George S. Patton, Jr., is said to have been especially gracious to the black truck drivers as a way of assuring his own supplies.

The success of the 16th Port at Le Havre may be measured in tonnage. In October 1944, a total of 62,319 tons of ammunition and other supplies were unloaded. In November the total increased to 171,541 tons, and in December it peaked at 203,926 tons.

Troop disembarkation was even more impressive. Besides the never-ceasing cries for more supplies of every kind, the call for frontline replacements for the dead and wounded grew louder. Thus, Le Havre became the leading Allied personnel entry point of the European Theater of Operations (ETO); a total of 1,887 personnel arrived in October, 89,825 in November, and 101,646 in December.

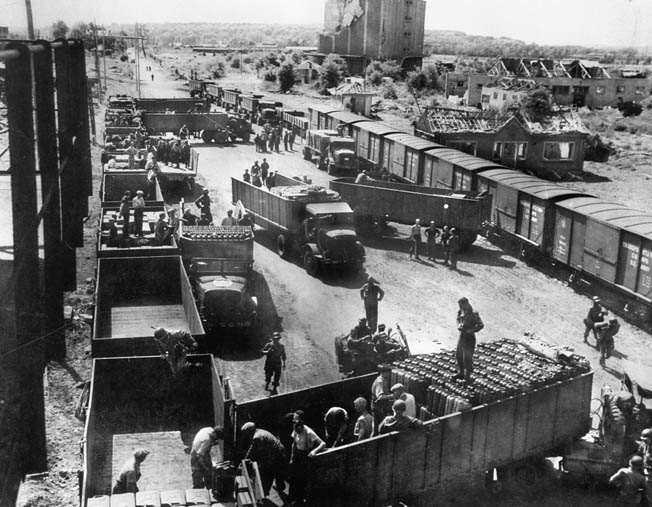

The arrival of sufficient quantities of ammunition was just as essential. Twenty-five trainloads left Le Havre for the front in October, 50 trains in November and, during December’s Battle of the Bulge, 92 trains of ammunition were rushed to the front. Ammunition handling was streamlined by separating bombs and artillery shells by type and size when they were unloaded from ships. This way they could be shipped in solid carloads and forward depots did not have to perform time-consuming searches for the right ordnance. Carloads of needed ordnance could be diverted to critical spots without further handling or documentation.

Le Havre was just one port. This massive supply effort was being duplicated all over northern France. In contrast, during the month of July 1942, at the very high-water mark of German General Erwin Rommel’s advance against the British at El Alamein, the Italian Navy managed to move 67,000 tons of material and 24 tons of fuel oil from Italy to North African ports. Here the Axis supply line broke down as supplies moved slowly from Tunisia and Libya forward to Egypt, causing the Afrika Korps’ advance to stall.

Recovering the Cargo of the Overman

Action in emergencies is an expected part of war. On the morning of November 11, 1944, the Liberty ship Lee S. Overman struck a German mine just outside the entrance to the Le Havre harbor. The mine left a gaping hole, but the captain had the presence of mind to beach his ship just before she cracked in two. The Overman’s cargo consisted of 36 two-and-a-half-ton trucks on deck and 6,000 tons of ammunition in the hold. The two broken halves of the ship began to bump and slam into each other from the choppy seas.

If the cargo were not immediately removed, the grinding metal of the ship’s two halves might catch a shell in its maw, triggering an explosion. French civilian stevedores were rushed to the scene along with two floating cranes. By 11 pm, the entire deck cargo, including the trucks, had been offloaded onto bobbing LCTs. Rising water and spilled oil in the hold made the removal of the volatile ordnance even more dangerous. Waves pounded the cranes and LCTs and soaked the men, but the unloading procedure continued until all the ordnance was removed and sent on its way to the front.

The Crucial Port of Antwerp

The port of Antwerp, Belgium, finally became available to the Allies in November 1944, when the last pockets of enemy resistance in the Scheldt Estuary were mopped up. As Antwerp opened to shipping, the importance of Le Havre as a port of entry began to decrease, even though total tonnage of supplies and ammunition shipped through the port continued to increase.

The Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 was Hitler’s last throw of the dice. His desperate bid to cut through the Ardennes in an effort to seize the Allies’ port at Antwerp brought supply demands to a fever pitch. At the same time, two engineering regiments attached to the 16th Port were sent into action.

The 392nd Engineers and Company E of the 373rd Engineers were issued weapons and hastened to the Meuse River, where they patrolled and prepared defensive arrangements should the enemy threaten that sector. They planted mines, guarded bridges, and prepared charges for demolition. The Germans, with much more serious supply problems than the Allies, pushed desperately toward the important supply depots in Liége, Belgium, but were denied.

Meanwhile, the besieged 101st Airborne Division, trapped at Bastogne, received 800,000 pounds of airlifted supplies in its valiant fight against superior German forces.

With the failure of their last desperate offensive, the German war machine in the West crumbled, but the U.S. Army Transportation Corps did not let up. Eleven days after British General Bernard L. Montgomery crossed the Rhine at Wesel, Germany, one of the widest stretches of the river, American engineers high-balled the first railroad train across a newly built bridge.

Heading Home From Le Havre

Le Havre was designated as the chief port of embarkation for the wounded and for liberated Allied prisoners of war returning home, so the 16th Port became responsible for setting up a huge camp and staging area at Le Havre for the former Allied POWs to prepare them to be taken to Britain and the States. The camp was called Lucky Strike, and at one time accommodated 47,000 freed POWs. With so many men to care for at once and the transports back to the United States limited in capacity, complaints about the camp soon found their way to General Eisenhower. A newspaper reported “intolerable conditions” in the camp, and Ike decided to investigate for himself.

Flying to Le Havre, Ike roamed the camps and listened to the men. Their two biggest beefs were the bland food and the slow pace of returning home. The cooks told the Supreme Allied Commander that doctors had been concerned that salt and pepper would not be good for dehydrated men. Ike ate a meal of the unseasoned food with the men and agreed but did not feel that he should overrule the doctors.

When he asked the soldiers if they would mind being overcrowded onto transports if it would get them home sooner, they chose that alternative over waiting longer for uncrowded passage. This set the stage for the huge throngs of soldiers on shipboard streaming into New York Harbor for joyful, tearful reunions. Other soldiers embarked through Le Havre for action in the Pacific.

Over A Million GIs Passed Through Le Havre

With final victory came reflection. Shortly after V-J Day, when the 16th Port statistics were added up, it was determined that over one million GIs had been redeployed through Le Havre for home or the Pacific. Two and a half million tons of war supplies had been unloaded there and moved to the ever-shifting front. It was an amazing record for a single outfit. The supply front had assured the victory of the Allied armies, and the 16th Port organization had played an important, if largely unsung, role in the ultimate victory.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments