By Roy Morris Jr.

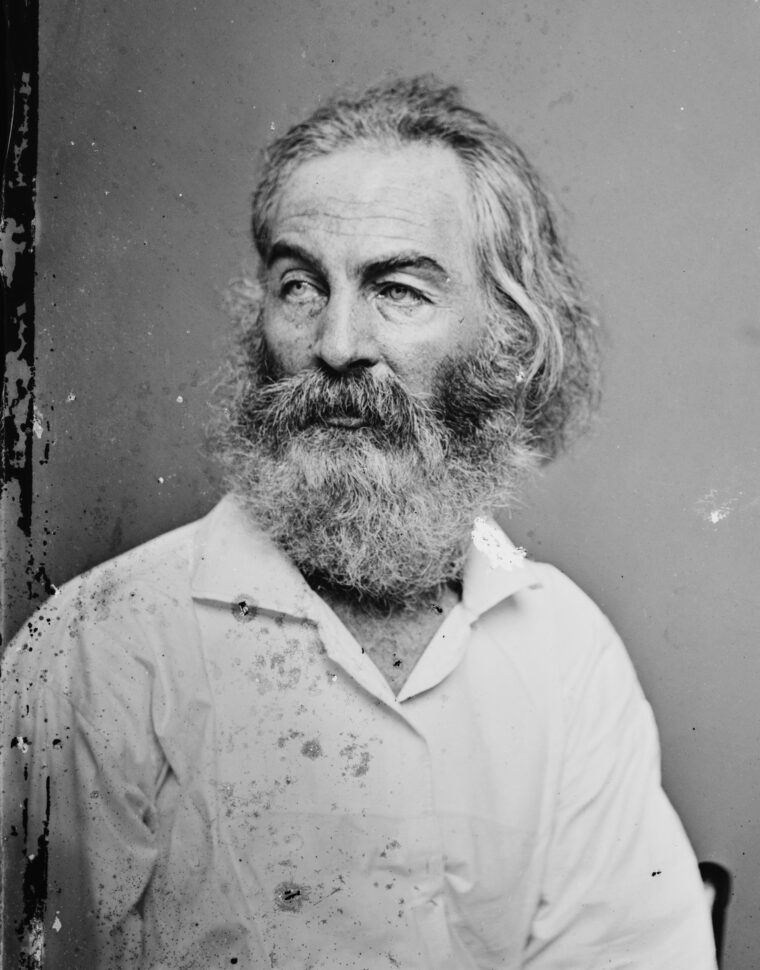

Walt Whitman arrived in Washington, D.C., in late December 1862, intending to stay for a few days. He wound up staying for the next 10 years. For the first three of those years, the great American poet was a regular visitor to the various military hospitals in and around the nation’s capital, where he devoted himself to bringing cheer and companionship to the thousands of suffering young soldiers confined to their beds with wounds, illness, or infection. By the end of the war, Whitman would personally make more than 600 visits to the hospitals and speak to some 100,000 soldiers during his rounds. In his own humble way, Whitman was also a war correspondent—not on the front lines of the battlefields, but in the rear, where the battles’ true costs were hidden away.

“A Sight in Camp”

Whitman’s time in Washington began with the wounding of his brother George at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in late December 1862. Walt was at home in Brooklyn with his mother on the morning of December 16 when he unexpectedly came across a list of regimental casualties in the New York Tribune. Among those listed was “First Lieutenant G.W. Whitmore [sic], Company D.” Fearing the worst, Walt threw together some belongings and hurried south to Washington, where the main Union hospitals were located.

For three days and nights Whitman searched in vain for his brother, trudging from hospital to hospital through streets clogged with dispirited Union soldiers and wild rumors of impending Confederate invasion. The futile period of searching, he told his mother, was “the greatest suffering I ever experienced in my life.” It did not help that Whitman’s pocket was picked in the train station in Philadelphia, leaving him literally penniless. At last someone suggested he go to Falmouth, outside Fredericksburg, where the Army of the Potomac was camped for the winter. There he found George in surprisingly good health, only slightly wounded by a piece of Confederate shrapnel that had pierced his cheek. George, for his part, was unfazed by his close brush with death and glorying in his promotion to captain of the 51st New York Infantry.

Whitman spent 10 days visiting his brother and the other soldiers in the regiment. He was struck immediately by how young many of the soldiers were. “The mass of our men in our army are young,” Whitman wrote in an article published in the New York Times. “It is an impressive sight to me to see the countless numbers of youths and boys, many of them already with the experiences of the oldest veterans.” Of the original 1,000 soldiers who had enlisted in George’s regiment at the start of the war, only about 200 still survived. Their patriotism, if not their numbers, remained high. “The men looked well to me,” Whitman noted in the Times article, “with the look of men who had long known what real war was, and taken many a hand in—a regiment that had been sifted by death.”

As a civilian, Whitman marveled at the men’s matter-of-fact attitude in the face of death. “Death is nothing here,” he wrote. “As you step out in the morning from your tent to wash your face you see before you on a stretcher a shapeless extended object, and over it is thrown a dark grey blanket—it is the corpse of some wounded or sick soldier of the regiment who died in the hospital tent during the night—perhaps there is a row of three or four of these corpses lying covered over. No one makes an ado.” He made notes for a new poem about one of the victims: “Young man, I think this face of yours the face of my dead Christ!” It would later become the basis of one of his most memorable poems, “A Sight in Camp.”

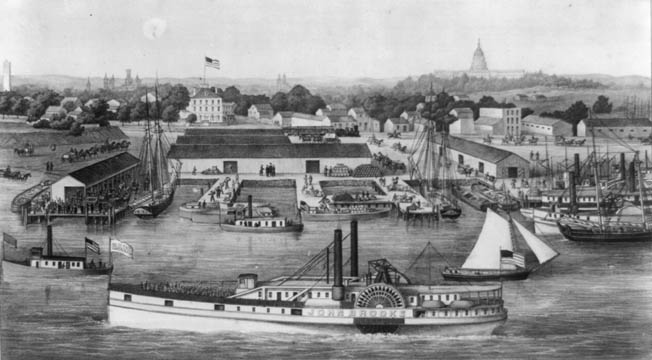

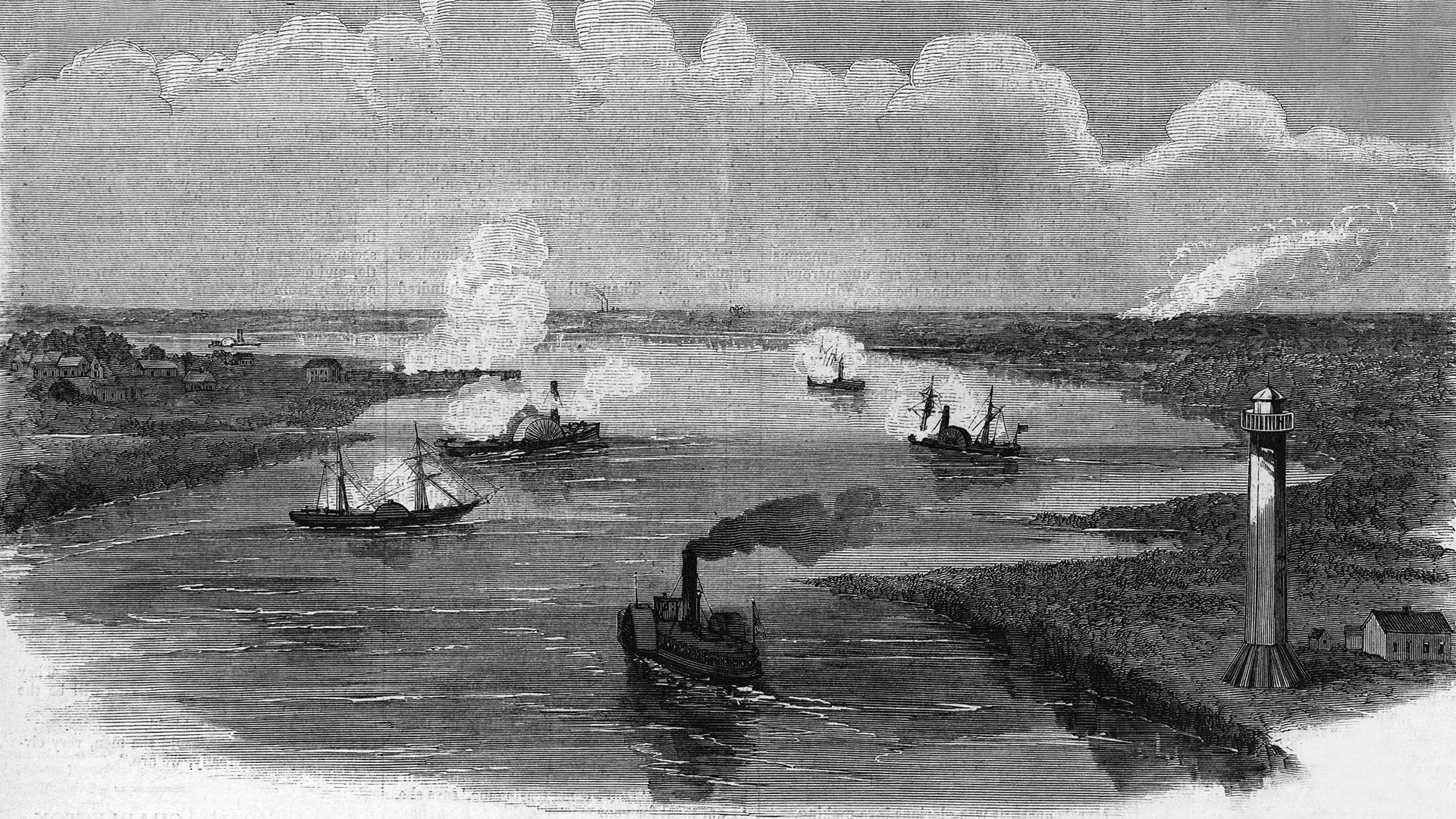

Whitman left Falmouth on December 28 aboard a government steamer bound for Washington. Traveling with him was a large contingent of seriously wounded soldiers headed for the various military hospitals in the rear. During the three-hour trip, Whitman went from man to man, collecting information to send to their families back home. It was the first humble step of a great one-man humanitarian enterprise. One of the men died before they docked at the Sixth Street wharf.

Back in Washington, Whitman found part-time work as a copyist in the paymaster’s office, where he saw firsthand the inadequate efforts by the government to aid wounded veterans. Each day he observed dozens of “poor sick, pale, tattered soldiers” climbing up five flights of stairs in search of back pay that was not always forthcoming. Many of the men had been honorably discharged from the Army, but without money to get home they were stuck in the hospitals and convalescent camps, surrounded by sick and dying comrades. Some were reduced to living on the streets.

The Shocking Conditions of Union Military Hospitals

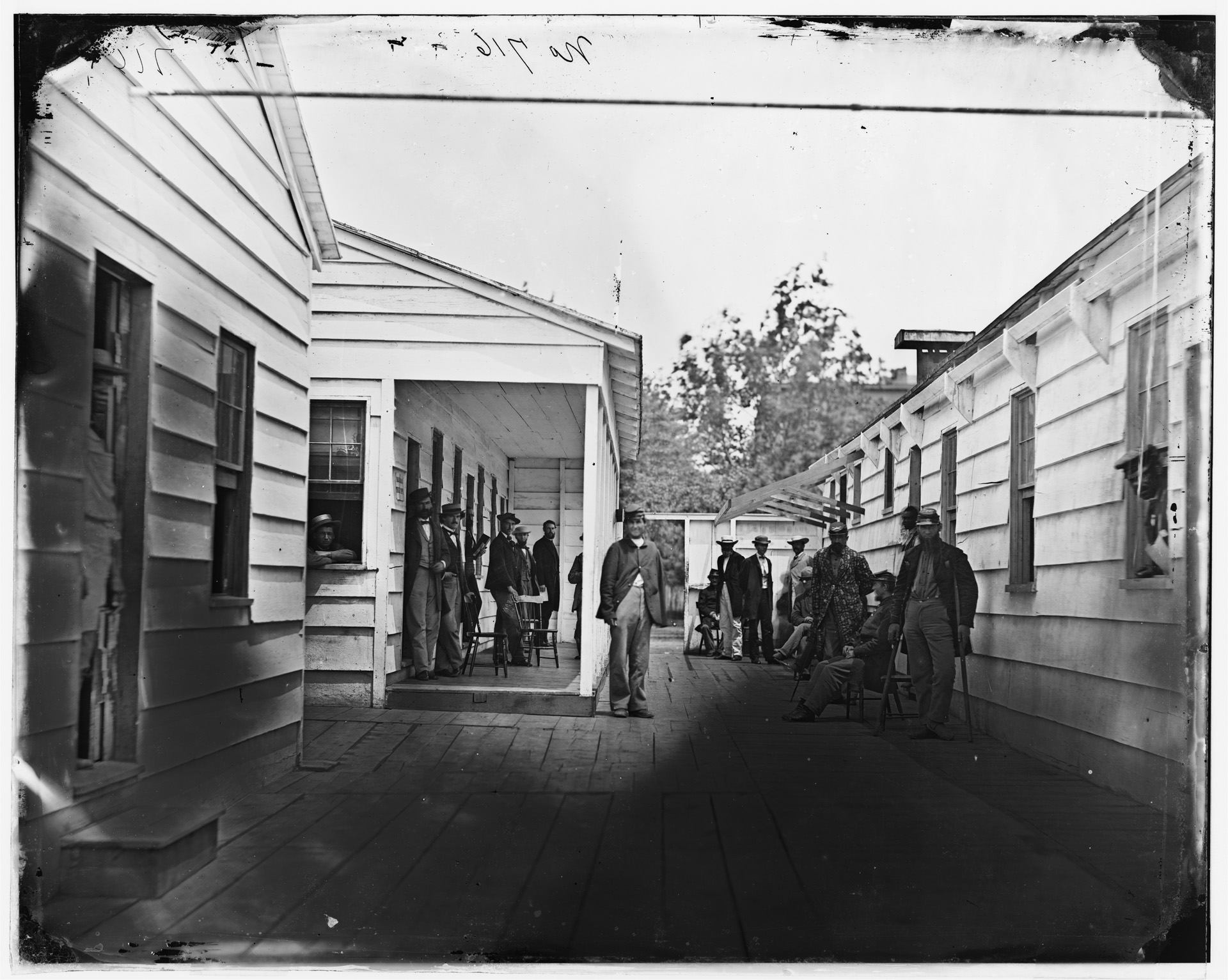

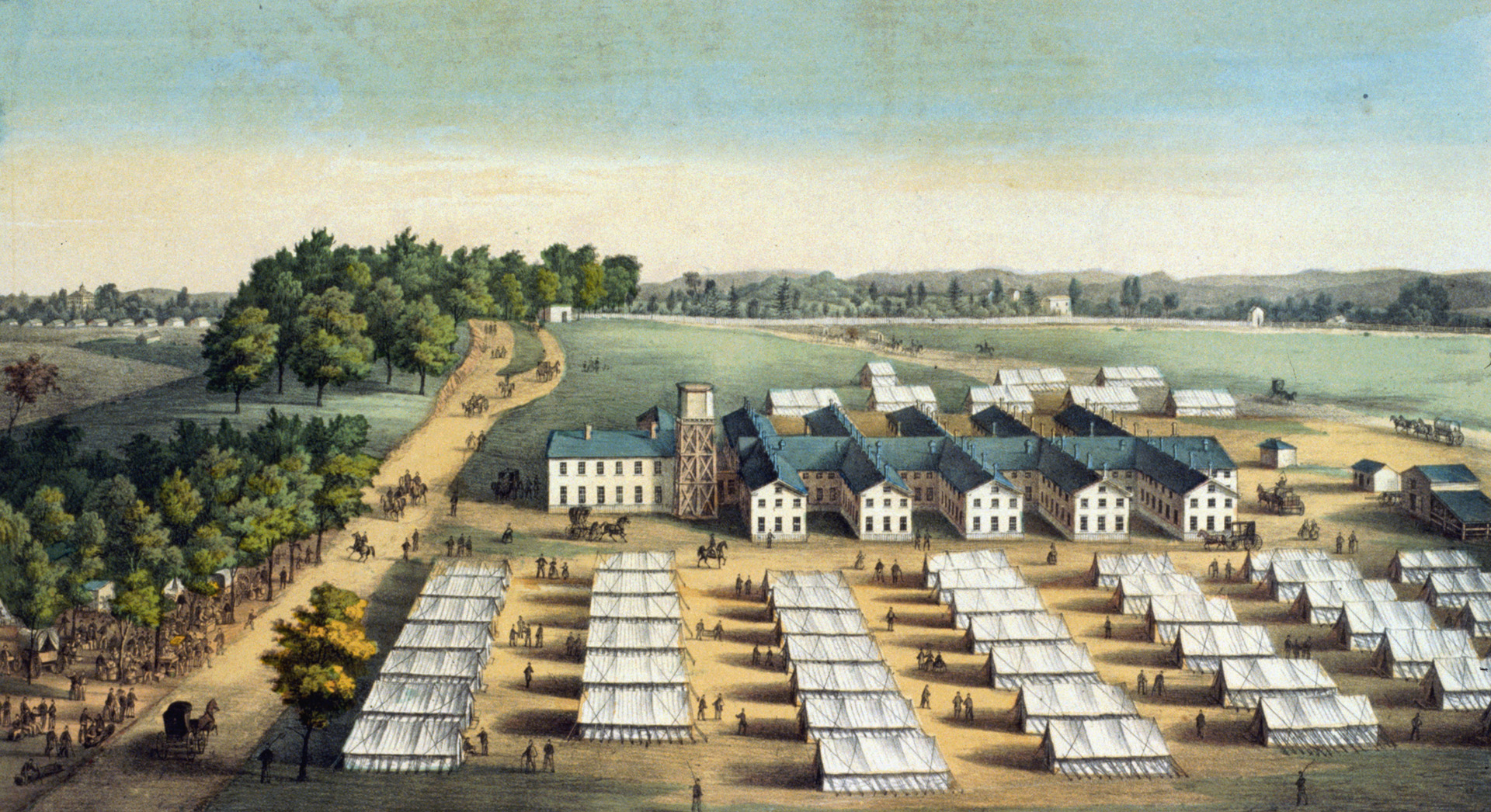

With no particular plan or purpose, Whitman began visiting the hospitals. At first, it was merely to look in on the Brooklyn soldiers he had known before the war, but it soon became a daily routine. In the past, Whitman had occasionally gone to visit injured friends at the Broadway Hospital in New York, but nothing had prepared him for the sights, sounds, and smells of the army hospitals—they were literally a world unto themselves. By the end of 1862, there were approximately 35 hospitals in Washington, accommodating some 13,000 soldiers.

These hospitals, ranging in size from converted private mansions to filthy, mud-encrusted tents in contraband camps, were places to be feared by any thinking person. The great European medical advances in bacteriology and antisepsis were still tragically a few years in the future, and the cause and prevention of disease remained unknown. Typhoid fever, malaria, and diarrhea, the three most prevalent and deadly killers in the Civil War, tore through every hospital and camp, spread by infected drinking water, contaminated food, and disease-carrying mosquitoes. Meanwhile, the overworked and understaffed physicians continued to ascribe the soldiers’ ills to such fantastical causes as “malarial miasms, mephitic effluvia, crowd poisoning, sewer emanations, and poisonous fungi in the atmosphere.”

Sick soldiers could expect little in the way of help from their doctors. Indeed, many of the physicians made matters worse by violating the most basic of all medical tenets: First, do no harm. The doctors prescribed a bewildering and ineffective array of drugs at the first sign of illness. Diarrhea was treated with laxatives, opium, epsom salts, castor oil, ipecac, quinine, strychnine, turpentine, camphor oil, laudanum, blue mass, belladonna, lead acetate, silver nitrate, red pepper, and whiskey. Malaria called for large doses of quinine, whiskey, opium, epsom salts, iodide of potassium, sulfuric acid, wild cherry syrup, morphine, ammonia, cod liver oil, spirits of nitre, cream of tartar, barley water, and cinnamon. When all else failed, doctors harkened back to more medieval methods of treatment: bleeding, cupping, blistering, leeching, binding, and chafing.

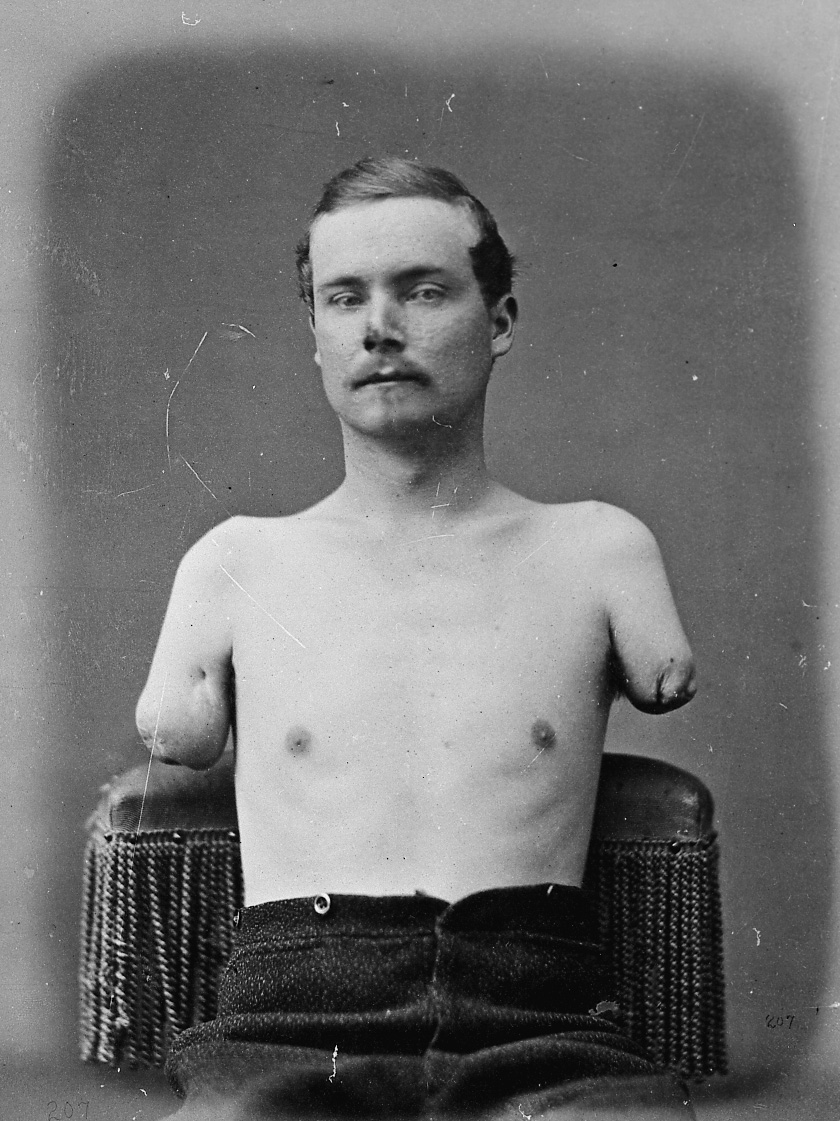

Sharing hospital space with the ill were soldiers suffering from bullet and shrapnel wounds. Frequently, they were recuperating from amputations of their arms or legs and, more often than not, were also battling some sort of postoperative infection caused by the hospitals’ incredibly filthy conditions. Union surgeon W.W. Keen, a young Philadelphia physician who went through the war with the Army of the Potomac, left behind a vivid description of the typical operating procedures at the time. “We operated in old blood-stained and often pus-stained coats,” Keen wrote. “We used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected cases, and marine sponges which had been used in prior pus cases and had been only washed in tap water. If a sponge or an instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of tap water and used as if it were clean. The silk with which we sewed up all wounds was undisinfected. If there was any difficulty in threading the needle we moistened it with bacteria-laden saliva, and rolled it between bacteria-infected fingers. We dressed the wounds with clean but undisinfected sheets, shirts, tablecloths, or other old soft linen rescued from the family ragbag. We had no sterilized gauze dressing, no gauze sponges. We knew nothing about antiseptics and therefore used none.”

The predictable result of such hurried and horrific operations was postoperative infection. Pyemia, septicemia, erysipelas, osteomyelitis, tetanus, and gangrene were grouped together as “surgical fevers.” Pyemia, literally “pus in the blood,” was the most dreaded of all, with a mortality rate of 97.4 percent, but the other surgical fevers also claimed their deadly share of victims. Not without reason did Civil War soldiers fear doctors much more intensely than they feared the enemy. They had a greater chance of dying in the hospital than in the field.

Walt Whitman’s Hospital Visits

From the start, Whitman’s hospital visits were good therapy for him as well as the soldiers. The brave, uncomplaining young men who were fighting and dying for the Union cause restored his belief in the inherent strength and goodness of the American people. Coming on the heels of a half decade of personal drift and depression, Whitman’s experiences in Washington were nothing short of life altering. As he later told a friend, “There were years in my life—years there in New York—when I wondered if all was not going to the bad with America, but the war saved me: what I saw in the war set me up for all time—the days in the hospitals.”

Whitman prepared for his daily visits as carefully as a general prepared for a battle. He quickly found that outward appearance counted greatly with the men, and so he made it a point to bathe, dress, and eat a good meal each afternoon before starting his rounds. “In my visits to the hospitals,” he wrote, “I found it was in the simple matter of personal presence, and emanating ordinary cheer and magneticism, that I succeeded and helped more than by medical nursing, or delicacies, or gifts of money.” He wore a cheerful, wine-colored suit, a pair of hand-polished black Moroccan boots, and a wide-brimmed hat with a gold-and-black drawstring and gold acorns at the bottom. He told his mother: “I fancy the reason I am able to do some good in the hospitals among the poor languishing and wounded boys, is, that I am so large and well—indeed like a great wild buffalo.” Small-town soldiers from the West and Midwest had never seen a man quite like him.

Realizing that the soldiers needed more than his mere presence to comfort and inspire them, Whitman began bringing a knapsack full of little treats for the men, anything he could beg, borrow, or buy to make their stay in the hospital a little easier. Fruit, tobacco, candy, jelly, pickles, cookies, wine, brandy, shirts, handkerchiefs, clean socks, and underwear all went into his gift bag. During warm weather he sometimes brought ice cream to the men as a special treat. These gifts he distributed quietly and informally, knowing instinctively that the proud young soldiers would automatically resist any hint of pity. He carefully kept track of his gifts in small pocket notebooks, jotting down whatever he had learned from the patients he visited—name, rank, company, regiment, bed number, ward, hospital, nature of wound, and names and addresses of parents and wives. He kept a ready supply of paper and pens on hand for those wanting to write home. If a man was too weak to write for himself, Whitman took down dictation or simply wrote the letter for him.

A characteristic entry from Whitman’s notebook reveals a typical morning in the hospitals: “Bed 53 wants some licorice; bed 6 (erisypelas) bring some raspberry vinegar to make a cooling drink with water; bed 18 wants a good book—a romance; bed 25 (a manly, friendly young fellow, independent young soul) refuses money and eatables, so I will bring him a pipe and tobacco, for I see how much he enjoys a smoke; bed 45 (sore throat and cough) wants horehound candy; bed 11, when I come again, don’t forget to write a letter for him. One poor German, dying—in the last stages of consumption—wished me to find him a German Lutheran clergyman. One patient will want nothing but a toothpick, another a comb, and so on.”

“Here Comes That Odious Walt Whitman”

Others were visiting the hospitals as well. At the time Whitman began his visits, there were 25 separate soldiers’ aid groups in operation—16 sponsored by the individual states—along with the United States Sanitary Commission and the Christian Commission. Whitman admired the Christian Commission, a purely voluntary organization he himself had briefly joined, but he did not think much of the Sanitary Commission, whose members were paid for their work. Nor did Sanitary Commission members think much of Whitman. One disapproving commissioner, Harriet Hawley, complained to her husband: “Here comes that odious Walt Whitman to talk evil and unbelief to my boys. I think I would rather see the evil one himself—at least if he had horns and hooves.”

The soldiers had a more favorable impression of their unconventional visitor. Union Colonel Richard Hinton, who met Whitman at Armory Square Hospital while recovering from a bullet wound suffered at Antietam, contrasted Whitman’s easy-going style with that of the starchy Sanitary Commission. “When this old heathen came and gave me a pipe and tobacco,” Hinton wrote, “it was about the most joyous moment of my life. Walt Whitman’s funny stories, and his pipes and tobacco were worth more than all the preachers and tracts in Christendom. A wounded soldier don’t like to be reminded of his God more than twenty times a day. Walt Whitman didn’t bring any tracts or bibles; he didn’t ask if you loved the Lord, and didn’t seem to care whether you did nor not.”

“The Great Army of the Sick”

To help finance his visits, Whitman fell back on his prewar training as a journalist. Like many other American writers, he had started working for newspapers as a boy, beginning as a printer’s apprentice on the Long Island Patriot at the age of 12. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, he had worked for 14 different newspapers, mostly in Brooklyn and New York City, but also including a brief stint as editor of the New Orleans Crescent in the late 1840s. Two years before the war, he had lost his most recent newspaper job, as editor of the Brooklyn Daily Times, for writing editorials defending the sexual rights of women.

Whitman published his first hospital dispatch, “The Great Army of the Sick,” in the February 18, 1863, edition of the New York Times. The article had a double purpose: to raise money for Whitman’s continued hospital visits, and to encourage others to join in the work. “A benevolent person, with the right qualities and tact,” he wrote, “cannot make a better investment of himself, at present, anywhere upon the varied surface of the whole of this big world, than in these military hospitals, among such thousands of most interesting young men. It is enough to make one’s heart crack.”

Whitman described one such heartbreaking encounter with a young Bridgewater, Massachusetts, soldier whom he found languishing at Campbell Hospital during one of his first visits. John Holmes, a 21-year-old shoemaker by trade and a member of the 29th Massachusetts Infantry, had been brought to the hospital suffering from a severe case of diarrhea. The disease, much more serious than modern versions of the complaint, affected 54 percent of all Union soldiers and a staggering 99 percent of all Confederates and eventually claimed the lives of nearly 100,000 men during the course of the war. Holmes himself was near death when Whitman found him lying untended in Ward 6 of the hospital. “He now lay, at times out of his head but quite silent,” Whitman reported, “asking nothing of anyone, for some days, with death getting a closer and a surer grip upon him; he cared not, or rather he welcomed death. His heart was broken. He felt the struggle to keep up any longer to be useless. God, the world, humanity—all had abandoned him.”

Whitman happened to pass Holmes’s bed on his way out of the ward, and noticed “his glassy eyes, with a look of despair and hopelessness, sunk low in his thin, pallid-brown young face.” The poet stopped and made an encouraging remark; Holmes did not reply. “I saw as I looked that it was a case for ministering to the affection first, and other nourishment and medicines afterward,” Whitman wrote. “I sat down by him without any fuss; talked a little; soon saw that it did him good; led him to talk a little himself; got him somewhat interested; wrote a letter for him to his folks in Massachusetts; soothed him down as I saw he was getting a little too much agitated, and tears in his eyes; gave him some small gifts and told him I should come again soon.” When Holmes mentioned that he would like to buy a glass of milk from the old woman who peddled it in the wards, Whitman gave him some money. The young man immediately burst into tears.

Whitman continued to look in on Holmes, who remained dangerously ill for several weeks before eventually recovering his health and rejoining his unit. “The other evening, passing through the ward,” Whitman wrote, “he called me—he wanted to say a few words. I sat down by his side on the cot in the dimness of the long ward, with the wounded soldiers there in their beds, ranging up and down. Holmes told me I had saved his life. It was one of those things that repays a soldiers’ hospital missionary a thousandfold—one of the hours he never forgets.”

“The Great Army of the Sick” was well received by readers and earned Whitman a congratulatory letter from managing editor John Swinton and an extra $50 for his work. Three weeks later, Whitman wrote a second article, “Life Among Fifty Thousand Soldiers,” for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Unlike the Times piece, this article was geared toward hometown readers, and Whitman took pains to mention by name as many of the local soldiers as he could. “At a rough guess,” he wrote, “I should say I have met from one hundred fifty to two hundred young and middle-aged men whom I specifically found to be Brooklyn persons. Many of them I recognized as having seen their faces before, and very many of them knew me. Some said they had known me from boyhood. Some would call to me as I passed down a ward, and tell me they had seen me in Brooklyn. I have had this happen at night, and have been entreated to stop and sit down and take the hand of a sick and restless boy, and talk to him and comfort him awhile, for old Brooklyn’s sake.”

“Washington in the Hot Season”

In August 1863, Whitman published another article in the New York Times, “Washington in the Hot Season.” The long article gave readers a good description of the nation’s capital in the midst of the Civil War. “Soldiers you meet everywhere about the city,” Whitman wrote, “often superb looking young men, though invalids dressed in worn uniforms, and carrying canes or, perhaps, crutches. I often have talks with them, occasionally quite long and interesting. I find it so refreshing to talk with these hardy, bright, intuitive, American young men (experienced soldiers with all their youth.) There hangs something majestic about a man who has borne his part in battles, especially if he is very quiet regarding it when you desire him to unbosom. I now doubt whether one can get a fair idea of what this war practically is, or what genuine America is without some such experience as this I have had for the past seven or eight months in the hospitals.”

A longtime admirer of Abraham Lincoln, Whitman often caught a glimpse of the careworn president riding through the city in an open carriage. “I saw the president in the face fully,” he reported, “and his look, though abstracted, happened to be directed steadily in my eye. I noticed well the expression. None of the artists or pictures have caught the deep, though subtle and indirect expression of this man’s face. They have only caught the surface. There is something else there.” The two giants of the age only nodded to each other in passing; they never formally met. Whitman did attend a reception in the Blue Room at the White House following Lincoln’s second inauguration, where he observed the President in the receiving line. “I saw Mr. Lincoln, dressed all in black, with white gloves and a claw-hammer coat,” Whitman reported, “looking very disconsolate, and as if he would give anything to be somewhere else.” It was the last time he would see Lincoln alive. The president was assassinated two weeks later, an event that occasioned Whitman’s greatest poem, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.”

Whitman published two other articles in the New York Times, “Our National City” and “Letter from Washington,” and the Brooklyn Union printed a short letter from him detailing the capital’s anxiety over the inconclusive military campaigning. He also worked sporadically on a new collection of poems, to which he gave the evocative title Drum-Taps. These poems ranged from the early recruiting poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” to the poignant, semi-autobiographical poem “The Wound-Dresser,” in which he ruefully recalled his earlier bellicose writing: “Arous’d and angry, I’d thought to beat the alarum, and urge relentless war,/But soon my fingers fail’d me, my face droop’d and I resign’d myself,/To sit by the wounded and soothe them, or silently watch the dead.”

Return to Brooklyn

Whitman’s own robust health gave way in the face of repeated exposure to sick and dying soldiers, and he was forced to return home to Brooklyn in mid-1864 to recuperate from an undiagnosed illness—possibly hypertension complicated by a bad cold. It was a wonder he hadn’t gotten sick before he did. “O the sad, sad sights I see,” he told his mother, “the noble young men with legs and arms taken off—the deaths—the sick weakness—sicker than death, that some endure, after amputations, just flickering alive.” Nevertheless, he returned to Washington six months later to resume his hospital visits and reporting. His final newspaper articles summed up the wartime adventures of his brother George and his fellow 51st New York veterans. “The 51st,” he reported in the New York Times, “has been in seven general engagements, and sixteen skirmishes—acquiring a reputation for endurance, perseverance, and daring, not excelled by any in the whole army of the U.S.”

His last wartime article, “Return of a Brooklyn Veteran,” published in the Brooklyn Daily Union on March 16, 1865, recounted with pride George Whitman’s return from a Confederate military prison in Richmond and his four years of dangerous service on the battlefields of Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia. “Of the officers that went with the regiment, not a single one remains,” Whitman wrote, “and not a dozen out of over a thousand of the rank and file. Most of his comrades have fallen by death. Wounds, imprisonment, exhaustion, &c., have done their work. His preservation and return alive seem a miracle. For three years and two months he has seen and been a part of war waged on a scale of amplitude, and with an intensity on both sides, that puts all past campaigning of the world into the second class.”

Of his own voluntary service as a witness to “war’s hell scenes,” Whitman maintained a lifelong modesty. “People used to say to me, Walt you are doing miracles for those fellows in the hospitals,” he told his young disciple Horace Traubel many years later. “I wasn’t. I was doing miracles for myself.” He never lamented his wartime service or what it cost him physically and emotionally. “I only gave myself,” he said. “I got the boys.” Half a decade before the war, he had written in Leaves of Grass, “I am the man, I suffer’d, I was there.” After the Civil War he could truly say that he had lived those words and helped, in his own way, to relieve the suffering.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments