By Gary Kidney

On December 8, 1941, America was still shocked by news of war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that the day before had been “a date which will live in infamy” because of the “unprovoked and dastardly attack” by Japan on Pearl Harbor. He noted that it was not a single event, but a pattern of attacks that included Hong Kong, the Philippines, Guam, Wake, and Midway Islands. In his speech, he interpreted “the will of the Congress … to defend ourselves to the uttermost.” Congress responded with a vote to declare war that made a still-famous front page of The New York Times.

Tremendous suffering and a smoldering need for revenge permeated the days following the attack, but something important is often lost. The congressional vote was not unanimous. Roosevelt did not understand the complete will of Congress. One person, filled with a seldom equaled strength of conviction, rose to challenge war. One single vote was cast against the declaration. One person said, “No.” That person was Jeannette Rankin, a representative from Montana. In addition to being the sole dissenter, history also records that she was the first woman in Congress.

Referring the Resolution to a Committee

Representative Rankin had been scheduled to speak at an event in Detroit on that day. She left by train on Sunday evening, December 7, for the event and took a radio along to follow the fate-filled news. When the radio announced that Congress was to hear Roosevelt’s request for a declaration of war, she got off the train in Pittsburgh and returned to Washington, D.C. She arrived at the capitol about noon and took a prominent seat in the first row of the House chamber for the important address.

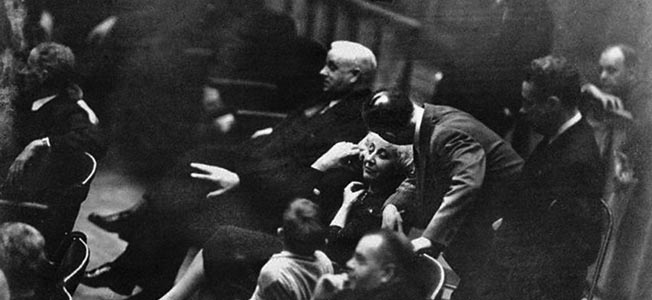

When the president finished his remarks, the House took up consideration of House Joint Resolution 254, the formal declaration of war. Sam Rayburn (D-Texas), Speaker of the House, asked, “Is a second demanded?” Jeannette Rankin rose. “I object,” she insisted, but the speaker overruled her. “No objection is in order,” he said

In a 1974 oral history, Rankin explained the purpose behind her objection. House rules allow any resolution to be referred to committee upon any member’s request. She wanted to ask for committee referral to “remove the war vote from the passion of the moment and have it at least considered so both sides of the issues could be brought out.” By refusing her objection, Speaker Rayburn effectively violated standard procedure and, as she later claimed, denied her the First Amendment right of free speech.

Objection overruled, a short discussion took place on the House floor. Then, a vote on the resolution was requested. Jeannette Rankin rose just after the question was called. “Mr. Speaker.” Rayburn ignored her and continued, “Those who favor taking this vote by the yeas and nays will rise and remain standing until counted.”

Rankin responded. “Mr. Speaker, I would like to he heard.” Speaker Rayburn continued, “The yeas and nays have been ordered. The question is, Will the House suspend the rules and pass the resolution?”

Rankin tried a third time. “Mr. Speaker, a point of order.” Rayburn responded, “A roll call may not be interrupted.”

When the vote came and her name was called, she answered “No.” Some historians claim that she elaborated on her vote by saying, “As a woman, I can’t go to war and I refuse to send anyone else.” The Congressional Record does not document this comment. Catcalls, hisses, and boos from the House floor as well as the packed gallery greeted her vote. Colleagues beseeched her to change her mind. However, by 1:10 pm she was still adamant, and the vote stood as recorded, 82 to 0 in the Senate and 388 to 1 in the House.

“Montana is 110 Percent Against You!”

Word of Rankin’s vote escaped the chambers and circulated among the mass of people who had flocked to the capitol. The crowd accosted her as she left the building, pushing toward her and shouting obscenities. She ducked into a phone booth and called capitol police for an escort to her office. There, she remained behind locked doors.

She called her brother, Wellington, in Helena, and his response was, “Montana is 110 percent against you!” She wrote an explanation of her vote to her Montana constituents, citing a campaign pledge to the “mothers and fathers of Montana … to prevent their sons from being slaughtered on foreign battlefields,” and ended her letter with “I feel I voted as the mothers would have had me vote.”

Response from radio commentators and newspaper columnists swiftly vilified Rankin. Many called for her resignation, and some of her constituents demanded her recall. A few accused her of disloyalty or treason. Montana newspapers expressed their dissatisfaction. The Miles City Daily Star of December 10, 1941, offered “humble and respectful apologies to the rest of the United States” for her vote. The Choteau Acantha of December 22 suggested a public spanking on the floor of the House with an old-fashioned hairbrush. On December 14, the Great Falls Tribune dubbed her “Japanette Rankin.” Despite the public reaction, Rankin was never apologetic for her vote.

On Thursday, December 11, when Congress considered separate resolutions of war on Germany and Italy, Rankin simply voted “present” for each roll call, a softer form of “no.” Her convictions and votes made her an outcast in Congress and left her to serve out her term with no chance of reelection. She took part in few floor debates, concentrating on minimizing the war’s effect on Montanans by, for example, strengthening draft deferments.

The Reason Behind Rankin’s Vote

Why did Rankin commit political suicide? Four theories have been advanced to explain her vote.

Some historians have taken Rankin at her words about women in war service and voting for mothers and chalked up her vote to a feminist stance. That view harmonizes well with Rankin’s suffragette activities. She had worked tirelessly in many organizations to achieve women’s voting rights. She helped North Dakota women gain the right to vote in 1913. She was successful in 1914 in her home state of Montana. On the strength of that notoriety and probably as a result of women voters, she was elected to the House of Representatives from Montana, serving from 1917 to 1919. That was her first of two discontinuous terms in Congress and the one that made her the first woman in Congress. On the national stage, she promoted ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, and in 1920 it gave women the right to vote everywhere in the United States. As a result of her work as a suffragette and for becoming the first woman in Congress, the National Organization of Women honored Jeannette Rankin at age 91 in 1972 as “the world’s outstanding living feminist.”

Another theory attributes Rankin’s vote to her humanitarianism and interest in social causes. During her post-college years, Jeannette read widely on social issues. A budding interest in social activism drew her to New York City and a Master’s program in social work at the prestigious New York School of Philanthropy. In her after-school afternoons, she engaged in practical social work that showed her the juxtaposition of crippling poverty and lavish wealth, the poor care given orphans, overcrowding in jails, and the lack of public sanitary facilities. She developed a thesis that a woman’s maternal instincts were valuable outside the home toward the improvement of society.

When working within the existing social work system proved unsatisfactory, Rankin took her activism in the political direction to aim for systemic changes. In 1917, after Anaconda Copper Company’s Granite Mountain mineshaft burst into flames and took the lives of 167 Montana miners, Jeannette rallied for better working conditions. Rankin’s concern for social ills and promotion of social actions led her to advocate that the foundation of democracy was human rights rather than property rights, as was then commonly believed. This took root when she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union as vice president. At Rankin’s death, she left a portion of her estate to assist mature, unemployed women workers. That endowment launched the Jeannette Rankin Woman’s Scholarship Fund.

An Outspoken Pacifist

In an episode of National Public Radio’s All Things Considered titled “The Lone War Dissenter,” Walter Cronkite attributed Rankin’s vote to her being an “outspoken pacifist.” One of Rankin’s most famous quotes is: “You can no more win a war than you can win an earthquake.” She perceived the violence and death of war as tragedy and never as triumph. Jeanmarie Simpson’s play and 2009 movie A Single Woman traces the root of Rankin’s pacifism to her learning of the Indian slaughter at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota on December 29, 1890, when Rankin was 10 years old. Rankin recalled: “As the Indians came out of their tents, the American soldiers shot them—shot the Medicine Man and anyone who came out. It was a most disgraceful act, the most outrageous thing that could happen.”

Jeannette carried her pacifism into her first term in Congress. On April 6, 1917, the first woman ever elected to Congress was to cast her first vote. In Kevin Giles’s book Flight of the Dove, he provides some melodrama to that Good Friday early morning by using as his central metaphor a flock of white doves that encircled the capitol. In that building, President Woodrow Wilson requested a vote on a resolution of war with Germany. Jeannette Rankin said, “I want to stand by my country. But I cannot vote for war. I vote NO.” Unlike her lone dissenting vote for World War II, 49 other representatives and six Senators voted for peace. Later, she reflected that this vote was “the single most important act of her life because of the way it crystallized her thinking from that point forward.”

Rankin reflected, “I have always felt that there was significance in the fact that the first woman who was ever asked in Congress what she thought about war, said ‘No!’” Rankin remained a spokesperson for pacifism. In 1968, at 88 years of age, she marched under the banner of “The Jeannette Rankin Peace Parade” with 5,000 women in Washington, D.C., to protest the Vietnam War.

Opposing Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Road to War

Rankin offered her own explanation on December 8, 1942, the anniversary of her vote, when she caused an essay to be entered into the formal Congressional Record. The essay, titled “Some Questions about Pearl Harbor,” offers several well argued cases that President Roosevelt was squarely to blame for Pearl Harbor and that he had abandoned his well-professed neutrality prior to the attack. She offered several pointed arguments to advance her opinion.

Her first thesis was that Roosevelt was manipulated by the British into a posture that could only lead to war. She cited a 1938 book by British author Sydney Rogerson titled Propaganda in the Next War, which she had read from the Library of Congress. The book called for British propaganda in the United States, during the next war, to target and build a fear of Japan, predicting that resulting economic sanctions against Japan would cause war and embroil the United States against Germany. Then, she focused on the Atlantic Conference of August 12, 1941, where Roosevelt had promised Churchill that the United States would bring economic pressure to bear on Japan. She noted that the Economic Defense Board had imposed that pressure less than a week later.

She argued that Roosevelt knew that economic and trade sanctions would lead to war. She cited a State Department Bulletin of July 26, 1942, in which Roosevelt admitted that cutting off oil to Japan would lead to war. Rankin reported that she had applied to the Departments of State and Commerce for statistical data for month to month trade between the United States and Japan prior to the war. Such a request was within the rights of a sitting member of Congress. She received a shocking response: “Because of a special executive order, statistics on trade with Japan beginning with April 1941 are not being given out.”

Her third thesis began with a quotation from Life magazine of July 20, 1942, where it was written, “…the Chinese, for whom the U.S. had delivered the ultimatum that brought on Pearl Harbor….” She cited it because the presence of an ultimatum as a cause of World War II was not yet widely or popularly understood. Then, she revealed that on September 3, 1941, a communication had been sent to Japan demanding that it accept the principle of “nondisturbance of the status quo in the Pacific.”

Finally, she offered several examples of military orders predating Pearl Harbor that indicated that war was known to be imminent. Once of the most compelling was the story of Lieutenant Clarence E. Dickinson, published in the Saturday Evening Post on October 10, 1942. He wrote about a mission to deliver a batch of 24 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter planes from Pearl Harbor to Wake Island on November 28, 1941. He claimed that the mission was “under absolute war orders” and that they “were to shoot down anything we saw in the sky and bomb anything we saw on the sea.”

Rankin reasoned that President Roosevelt had been earnestly working to entrap the United States in war. She thought Pearl Harbor was a massive stroke of luck for him. At the conclusion of her Congressional Record essay, she wondered: “But was it luck?”

Amid wartime secrecy and a lack of direct information, her analysis has proved rather insightful. Her speculation about Roosevelt’s causality of World War II was among the first in what has become a 60-year history of conspiracy theory and spawning more than a dozen books. One of those was written by Congressmen Hamilton Fish (R-NY). He was a noninterventionist, who, in the House debate, laid aside that philosophy and endorsed the war. Later, he believed that Roosevelt had planned for war for quite some time and had tricked the country into involvement.

Jeannette Rankin’s second term in Congress ended in January 1943, just weeks after her Congressional Record essay. In North Africa, German General Erwin Rommel was in full retreat. In the Pacific, battles at Midway and in the Solomons showed a turning tide. Field Marshall Friedrich von Paulus’s German Sixth Army was only weeks away from surrender at Stalingrad. Some glimpsed the end of the conflict, and it became necessary to plan for such an end. Although a Supreme Allied Commander had yet to be named, staff developed a plan for the war’s end and the peace thereafter. Either as irony or homage, this plan was code named Operation Rankin. The Rankin plan served as the basis for D-Day and the occupation zones of a postwar Germany.

Jeannette Rankin’s Legacy

Jeannette Rankin died on May 18, 1973, at age 92, in Carmel, California. History, for the most part, has relegated her to the role of footnote, a woman whose misguided adherence to a set of causes led her to dissent against one of the most popular wars in American history. She achieved a brief glimpse of remembrance when Congresswoman Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) stood alone against the war on terror following 9/11, echoing Jeannette’s convictions of 60 years earlier.

However, in the United States, strength of cause and conviction has always been valued. Jeannette’s ability to stand alone for her beliefs is admirable, maybe even heroic. Questioning leaders, their motives, and their principles is not only a fundamental right but an important duty in a democracy. Jeannette fulfilled that duty despite the unpopularity it caused.

Even more valuable is the voice of dissent. Dissent was fundamental before the words liberty, freedom, equality, and pursuit of happiness were ever celebrated in the United States. Jeannette Rankin should be more than a Trivial Pursuit answer or Jeopardy question. Her contribution to the history of this land should be often remembered.

As a high school junior in an American History class, the author earned extra credit by attending a lecture by Ms. Rankin at a local university. At that time, many things were burning—draft cards, brassieres, protesters in self-immolation, flags, crosses, and napalm. Ms. Rankin was a woman of wit and wisdom. Her speech was feminist, humanist, and pacifist, showing that the causes of her life were still fresh and energizing to her. Her speech was both thought provoking and transformative to at least one teenager whose mind still reeled from the deaths of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. During her talk, she said: “There can be no compromise with war; it cannot be reformed or controlled; cannot be disciplined into decency; cannot be codified into common sense.”

Those words were on the author’s mind one February day in 1972, watching on television with no draft deferment as his birthday was drawn 19th in the Selective Service Lottery. The author would have served, but thanks to Jeannette Rankin, and others of like mind, he did not have to.

Interestingly she also cast a vote against entering WW I where she was on much more solid grounds considering Wilson’s inept handling of European relationships and American preparedness. Pearl Harbor was a good deal more straight forward although American preparations were once more quite untimely.