By Louis Ciotola

The Dutch revolt against Spain reached one of its many climaxes on July 10, 1584, when an assassin took the life William the Silent, stadtholder of the new Dutch Republic and the most prominent member of the House of Orange. Without warning, the Dutch had lost the individual most emblematic of their cause. There was no question the rebellion would continue; in fact, the governing States-General voted the following month in favor of battling on. The real question was who would lead in William’s place.

Among the new members of the Council of State, which the States-General appointed that August to help carry on the war with Spain, was 16-year-old Maurice, Count of Nassau, the second son of William the Silent. Maurice’s appointment was purely political. He and his many cousins were a highly influential clan. Their talents and family connection to William were certain to have a unifying effect on the war effort and provide a boost to the rebellion in the dark days following William’s death.

The rebellious Dutch provinces declined to elect a universal stadtholder in place of William. Instead, each province selected its own leader. Holland and Zeeland chose Maurice upon the occasion of his 18th birthday, but the title was largely honorific. Maurice’s task was to serve the two states while the civilian government created and directed actual policy. It was his specific duty to serve as commander of the Army of Brabant and Flanders. By 1589, all of his fellow stadtholders were either members of the House of Nassau or the House of Orange, freeing Maurice from his political duties and allowing him to focus on the formidable challenge of making war against the mighty Spanish Empire.

The 30,000 Spaniards in the Netherlands

While Maurice educated himself in the ways of war, the Spanish were at the peak of power. Warfare in the late 16th century was an almost entirely defensive art, and the Spanish had mastered it. The expanding science of fortifications increased the importance of sieges and lessened the impact of pitched battles. In the Netherlands, where towns sat relatively close together, mobile cavalry gave way to infantry, and it was in infantry tactics that the Spanish truly excelled. The basic Spanish unit of infantry was a virtual mobile fortress. The Spanish square, or tercio, was formed by a mass of foot soldiers called an escuadrón. Once numbering as many as 5,000 men, the average escuadrón had shrunk to roughly 1,500 men by the waning years of the century. Each escuadrón was composed of approximately two-thirds pikemen and one-third musketeers, drawn together on a broad front of five ranks. Massive in proportion, the escuadrón intimidated all opposing forces that lay in its path.

At the time Maurice began his military career, Spain’s Army of Flanders was gradually coming to dominate the war in the Netherlands. Up the so-called Spanish Road through Italy and Germany flowed men and money to the talented Spanish general Alexander Farnese, the Duke of Parma. Parma had just completed his crowning achievement, the brilliant capture of Antwerp, when suddenly the entire political landscape changed dramatically. At the very moment Parma finally had the Dutch on the ropes, King Philip II of Spain inexplicably relieved the pressure by turning his attention to Protestant England. In 1588, the Spanish Armada met its doom, leaving Parma sitting uselessly on the Flanders coast awaiting a Channel crossing that was not to be. The following year, Philip expanded his obligations still further with a pledge of assistance to the French Catholic League. When the king dispatched Parma to fight the Protestant Huguenots in France, the Dutch were free to exploit his inopportune departure.

Roughly 30,000 Spanish troops remained in the Netherlands, nearly all garrisoning some town or fortress. No centralized Spanish army remained in the field. Maurice and his 10,000-man force were poised to take advantage of Parma’s absence. Starting with the relief of Bergen-op-Zoom, a decade of unbridled success began for the young stadtholder, whose unforeseen abilities would quickly make the Spanish regret not having finished off the obstinate Dutch when they had the chance.

Maurice could not claim all the credit for his success. His many cousins proved equally talented, especially William Louis of Nassau, commander of Dutch forces in the northern provinces. Not only were Maurice and William Louis able to cooperate as independent commanders, but as avid admirers of the Greeks and Romans, they sought to emulate the ancients in every way, from a mathematical study of siegecraft to the intimate formation of rank-and-file troops. The most significant result of their obsession was what became known in Europe as the “Dutch exercises.”

Achieving a Two-Minute Reload

The fundamental problem that Maurice and William Louis set out to tackle was a slow rate of infantry fire. The typical line of musketeers could unleash only one volley before being overrun by a determined enemy onrush. Any army that could improve upon this rate of fire would command a significant advantage on the battlefield. To accomplish their objective, the cousins agreed that their ranks would have to be extended to increase the size of an individual volley and create the opportunity for a more rapid rate of discharge once the ranks had more room to fall back and reload. The new tactic required a revolutionary, new kind of drill. A third cousin, John of Nassau, contributed to fill that need.

Each soldier in the revised units needed to learn a series of well-timed steps in order to efficiently implement the new tactic. John of Nassau put those steps to paper in the world’s first illustrated drill manual. The manual contained 15 drawings for pikemen, 25 for arquebusiers, and 32 for musketeers. When converted into actual commands, the pikemen practiced 31 maneuvers, while the musketeers trained for over 40, including the maintenance of formation, simultaneous fire, counting in unison, and countermarching.

Besides increasing the length of each rank, the Nassau cousins drastically reduced the size of each unit, making them far smaller than their Spanish rivals. They believed that smaller units would train and coordinate more effectively together, adding to increased battlefield mobility. The standard unit became the half-regiment. The half-regiment consisted of 250 pikemen flanked on both sides by 80 musketeers drawn up in files of 10. For greater protection, each half-regiment was in turn flanked by cavalry and arranged in a checkerboard formation. The cavalry, converted largely from lance to wheel-lock pistol, also decreased in rank to more easily perform a type of volley and withdrawal known as the caracole.

Maurice incessantly drilled his men throughout the 1590s. Soon, the Dutch half-regiments could conduct numerous turns and marches without the slightest confusion. The soldiers could reload their weapons (all of identical caliber) in the two minutes between being in the back rank and moving to the front, and they could also conduct an organized fallback to the fifth or sixth rank amid close-quarter pike combat or a cavalry charge. There, they would continue their deadly work at point-blank range.

The Triumphs of Maurice

The Spanish preoccupation with France and England contributed measurably to Maurice’s success, but he also devised an intelligent overall strategy. Maurice understood the limitations of Dutch resources. Expelling the Spanish from the rebellious provinces was one thing, but attempting to conquer outside the region was unrealistic. It was more feasible to obtain firm control over the areas immediately surrounding the maritime provinces and create a buffer zone protecting vital naval and commercial interests. Any attempt to spread the rebellion into the pro-Spanish southern provinces, Maurice thought, risked overreaching. Instead, his plan for consolidation of gains required numerous sieges of inland towns. Maurice, with his methodical nature and mathematical studies, proved ideally suited for carrying this out.

Over the next eight years, Maurice and his army moved from victory to victory, capturing town after town with great speed while suffering almost no setbacks. Applying the most advanced tactics of the day, Maurice concluded the majority of sieges within a few weeks while his clever logistics, such as using the region’s many rivers to quickly transport cannon, hastened the time until the next operation could commence. Maurice’s first coup came in 1590, when he employed trickery to take Breda in a nearly bloodless victory. The list of captured towns following Breda read like a map of the entire region: Geertruidenberg, Groningen, Graves, Zutphen, Deventer, Hulst, Nijmegen, Steenwijk, and more. The Dutch appeared unstoppable.

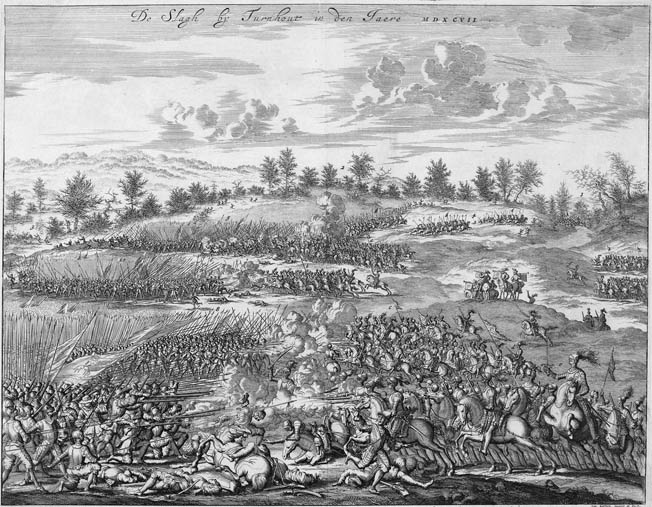

There was even an open-field triumph at Caervorden, where Maurice beat back a rare Spanish attempt to break a siege. An even more impressive victory occurred in January 1597 at Turnhout. There, the Dutch cavalry defeated a like number of Spanish cavalry and mercilessly decimated the supporting enemy infantry. All the while, Maurice was careful to protect his gains, rejecting a States-General scheme to drive through the southern Netherlands and link up with the French Huguenots. Such ideas could only serve to wreck years of progress, Maurice argued. Personally, too, he had made significant gains. By the close of the decade, all the rebelling provinces had appointed him their stadtholder.

Spain’s Financial Woes

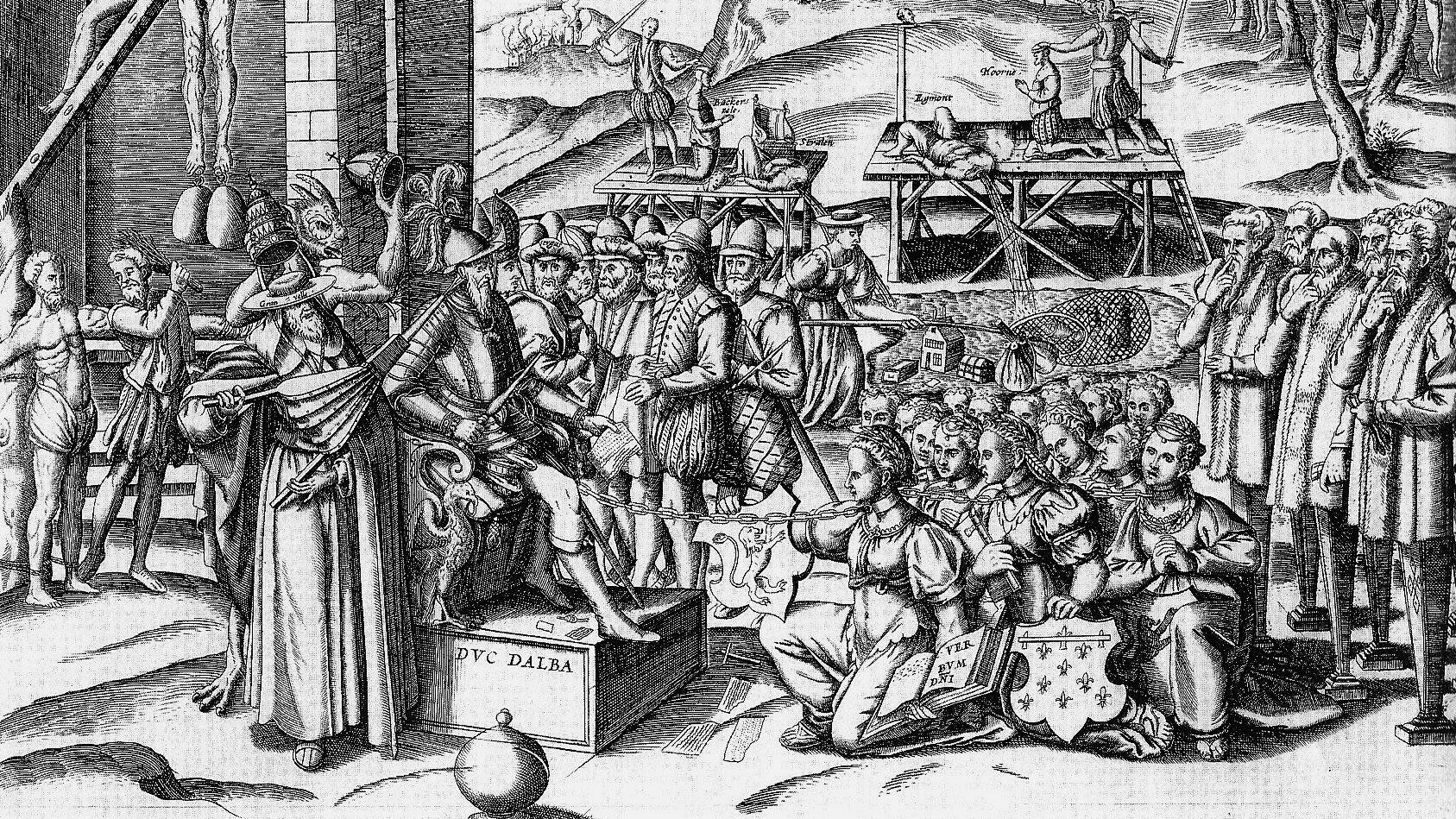

In 1593, the Duke of Parma died. Never again would his skills haunt the Dutch. Following a few short-lived successors, Archduke Albert, son of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian and son-in-law to King Philip II, accepted the position as next governor of the Netherlands. Unlike his two immediate predecessors, Albert had no intention of sitting on his hands in Flanders. Instead, he sought to challenge Maurice by dominating the Flanders coast and creating a seaborne menace to Dutch shipping. Almost as soon as the Spanish resurgence began, however, it came to a screeching halt. In 1596, the empire suffered one of its all-too-frequent bankruptcies. The Army of Flanders was paralyzed. The future boundaries of the United Provinces seemed largely set.

On May 6, 1598, an aging Philip II elevated Albert and his wife Isabella to the status of independent sovereigns. The Archdukes, as the couple was somewhat affectionately known, were, however, far from independent. Despite having achieved a peace with the newly converted Catholic king of France, Henry of Navarre (a peace the Dutch tried desperately to derail), the situation for the Spanish in the Netherlands was growing worse. Unpaid for many months, the troops began to mutiny on a large scale. In many instances they were literally starving. The disgruntled soldiers even sold the island fortress of Bommelerward back to the Dutch in compensation for lost wages.

As Spain’s economy struggled, Dutch finances boomed. Thanks to the physical protection provided by Maurice, the provinces were utilizing their sea power as never before. Albert was well aware of his rival’s prosperity. If he could not triumph militarily, he would turn to economic warfare. He intensified his strategy of harassing Dutch supply ships through the use of privateers. The States-General, ever sensitive to critical economic interests, took immediate notice of Albert’s tactics.

Political Pulls on Maurice’s Campaign

Maurice’s strategy of consolidation had succeeded beyond all expectations, and he saw no reason to risk the gains with unnecessary gambles. The States-General pointedly disagreed and in June 1600 made the monumental decision to invade Flanders. Their reasons appeared sound. First and foremost was the effect the Spanish privateers were having on the Dutch economy. If the provinces were to thrive, the privateers operating out of Dunkirk would have to be silenced. Should the campaign prove successful, Dunkirk could then be sold to the covetous English in exchange for additional debt alleviation.

Maurice, as usual, strongly opposed the new campaign. The Dutch army, he argued, lacked the means to endure for long within hostile territory. In order to succeed, it would have to hold extensive territory inland, something it was never designed to do. Maurice declared the plan “not feasible and too hazardous.” Both William Louis and the cousins’ talented English ally Francis Vere agreed. Not only would the Flemish population fail to rise, but Albert would end the mutinies by mustering the army to meet the outside challenge.

One of Maurice’s shortcomings was an inability to stand up to politicians. Understanding full well that failure would mean the loss of the Dutch field army and endanger the rebellion itself, Maurice nevertheless conformed to the new Dutch republicanism that gave civilians ultimate control of the military. He would obey the States-General. He did, however, insist that members of the government accompany the army into Flanders. Should disaster occur, he wanted the politicians to realize their folly firsthand.

1,250 Vessels, 13,000 Infantry, and 2,800 Cavalry

Maurice arrived in Flushing to supervise the army’s assembly on June 19. The plan called for some 1,250 vessels, most of which were simple barges, to transport the invasion force roughly 35 miles south to the Flanders coast and the Dutch-held town of Ostend. For protection and support, 16 men-of-war joined the flotilla. A total of 13,000 infantry and 2,800 cavalry, including German and Swiss mercenaries recently made available following the Franco-Spanish peace, boarded the waiting ships.

Right from the start, things went wrong for the Dutch. On June 22, the army of Zeelanders, Hollanders, Frisians, Walloons, Germans, Swiss, English, and Scots landed far west of their intended target of Ostend and instead, thanks to bad weather, was forced to disembark near the fortress of Philipine. Count Ernest of Nassau, commanding the advance guard, was the first to come ashore. The rest of the army followed and assembled for the march behind Ernest, with Count George Everard Solms leading the center and Vere at the rear. Upon completing the landing, Maurice ordered the fleet to disperse as a precaution against capture.

It soon became apparent that the Flemish population had no desire to join the Dutch rebellion. Maurice’s first target was the seaside town of Nieuwpoort, and local peasants fled before the invaders and harassed them from hideouts in the interior. Forcible retribution followed that only served to deepen the rift between the Flemish and the Dutch and all but guaranteed the perpetual separation of the North and South Netherlands. There was as yet no foreseeable threat from the Spanish Army, but Maurice fully expected one to come. In the meantime, the problems of the march were enough to occupy his mind. While the politicians lamented the local resistance, the tired soldiers trudged through the marshy terrain, scrounging for supplies and cursing the lack of fresh drinking water.

Boosting Morale in the Spanish Ranks

Archduke Albert defied all of the States-General’s expectations by proving to be a talented general. He learned of the Dutch landing shortly after it occurred and sprang into action with an energy that put his detractors to shame. Quickly assembling an army, Albert summoned troops from various garrisons while messengers scrambled to alert the 5,300-man force of Don Luis de Velasco, which hastily marched west upon receiving the order. Still, there remained the problem of the mutineers, largely gathered inside the towns of Diest and Weert. At this dire time, a renewal of their loyalty was of the utmost urgency.

Arriving at Diest, Albert unleashed every weapon in his arsenal to persuade the mutinous soldiers to fight. The Spanish soldier was swayed by religion, so the archduke made certain to portray the Dutch invasion as a Protestant threat to Catholicism. The Spanish soldiers were also swayed by pride, so Albert reminded them that a Dutch triumph would put them to shame. With no time to bargain, the archduke consented to the mutineers’s demands to receive their pay immediately, to be led by their own officers, and to bathe in the glory of being placed in the front rank of the entire army. Thus placated, the mutinous soldiers committed to the fight.

The Spanish army, numbering 11,000 infantry and 1,400 cavalry, assembled at Ghent on June 28. Standing by her husband’s side, Isabella addressed the troops, affectionately calling them her lions and invoking their honor. The following morning, the Dutch forces reached Nieuwpoort and began preparing to besiege the town. Nieuwpoort sat on the south side of the Yser River tidal estuary. To besiege the port, the Dutch had to cross to the left bank of the Yser. Ever cautious, Maurice chose to do so with only two-thirds of his force, leaving Ernest behind on the right bank with the remaining third in case trouble should arise.

Dutch Withdrawal Across the Yser

Fighting erupted early on June 30 when Albert led his army toward Ostend, capturing the redoubts at Snaeskerle and Oudenburg. Surviving defenders scrambled back to the safety of Ostend, which soon found itself cut off from all communications with the Dutch army at Nieuwpoort. Despite having been careful not to underestimate his enemy, Maurice was nevertheless taken aback by Albert’s show of strength. The members of the States-General traveling with the army now understood the wisdom of their general. But Maurice had little time to gloat over his predictions. His army was trapped, and it would take all of his talents—plus a lot of luck—to save the rebellion.

Two-thirds of his army was on the wrong side of the Yser. Should Albert catch him there, he would be annihilated. Even worse, by the time Maurice fully comprehended the situation, the river was swollen by high tide. The army would not be able to cross until low tide at 9 the following morning. Retreat was impossible—the army could never hope to board its ships in time. Battle was the only option, but to have any chance of success, Maurice somehow would have to delay the Spanish until his own army was safely across the river.

By default, that responsibility fell on Ernest and the advance guard, which were the only Dutch forces in position to carry out the mission. Maurice ordered Ernest and his force of 1,500 Zeelander and Scottish infantry and a handful of Dutch cavalry to hold the bridge at Leffingen and prevent the Spanish crossing at all cost. Once again, the Spanish were one step ahead. Much to his horror, upon reaching the bridge at Leffingen at 8 am on July 2, Ernest discovered that his foe was already in control of the bridge and had superior numbers. He nevertheless planted his force on the Leffingen road, hoping his two cannons would prove decisive. It was nothing short of a suicide mission. After waiting only momentarily to assess the situation, Albert sent his men storming forward, 3,000 in all.

The Spanish infantry charged straight ahead, absorbing four cannon volleys before overrunning the Dutch guns. At the same time, Spanish cavalry smashed straight into the Dutch flanks. The whole affair was over almost before it began. Ernest’s entire command abandoned their cumbersome weapons and fled. The desperate men became trapped in the sand and were mercilessly butchered by their pursuers. Nearly 1,000 corpses littered the field, most of them the characteristically stubborn Scots who had fought the longest. Although a heavy loss, their sacrifice was not entirely in vain. Ernest’s men had accomplished their basic purpose, if only by exhausting the enemy during their pursuit. By 11:30, the Dutch army was safely across the Yser, sitting on the sandy beach with Nieuwpoort and the river to its back. The Dutch were still hemmed in, however, and the Spanish had already vowed to take no prisoners.

“Take Your Choice. Mine is Already Made”

Albert provided the Dutch with a little extra time to prepare. Despite his superior position following the Leffingen action, his men were exhausted from the march through the sand. He considered digging in and leaving the enemy trapped on the beach. But the mutineers manning the first ranks would hear none of it. They had come to fight. The last thing they wanted to see was the Dutch sneak away onto their ships, robbing them of their glory.

Maurice, at any rate, planned to do no such thing. Leffingen may have been a disaster, but attempting to board ships in the face of the enemy would risk an even greater one. He ordered his transports to disperse in full view of the Spanish. He wanted to tempt Albert into attacking and also wanted to motivate his own men. Maurice dismissed Vere’s suggestion to construct entrenchments for fear this might delay the Spanish attack and allow time for word of Ernest’s calamity to spread among the rank and file. Open battle was the only option—the sooner the better.

The Dutch commanders were eager for battle. Louis of Nassau, first to assemble on the beach, begged his cousin for permission to charge his cavalry. He hoped to lure the Spanish cavalry dangerously forward by following the charge with a feigned retreat so that the six Dutch cannons positioned on the beach could open on the stunned enemy. Much to Vere’s dismay, Maurice sanctioned the attempt in the hope of stealing a quick victory. Initially, the operation bore the desired effect, provoking a countercharge by the excitable mutineer horsemen, but the cannons opened fire prematurely, alerting the Spaniards to the danger.

Following that opening engagement, quiet again settled on the beach. Maurice shifted Louis’s cavalry and the six cannons to the left flank. Vere, with his English and Frisian infantry, continued to man the front while Solms formed behind him with German, Swiss, French, and Walloon foot soldiers. The Spanish could clearly see Maurice in full armor riding before his army shouting words of encouragement. “My friends! We must now either fall instantly and with all our power upon the enemy, or be driven into the sea,” Maurice shouted. “Take your choice. Mine is already made.” A Dutch officer stated it more grimly. “If we do not overcome the enemy,” he warned, “we must drink up all the water of the sea, for there is no way of escaping unless we could march away by the dry bed of the ocean.”

Albert too paraded before his men, fearlessly riding his white stallion without a helmet to show himself to the troops. The Spanish arranged themselves in a similar manner to the Dutch. Three Spanish and one Italian escuadrón composed the center of the army, with two Walloon and one Irish regiment to the rear. At the forefront, as previously agreed, were the ravenous mutineers commanded by the equally ravenous Admiral of Aragon, known as the “terror of Germany and Christendom.” His cruelty matched his infamous nickname.

Assembling on the Dunes

For two hours the armies stood facing each other on the warm beach. The occasional cannon fire did little to rattle either side, but fire from Dutch warships offshore was beginning to disturb the easily targeted escuadróns. Meanwhile, the tide slowly crept in, eating away at the prospective battlefield. Soon there would be no room for the Dutch to wield their cavalry. Both sides determined independently that a new battlefield would have to be chosen.

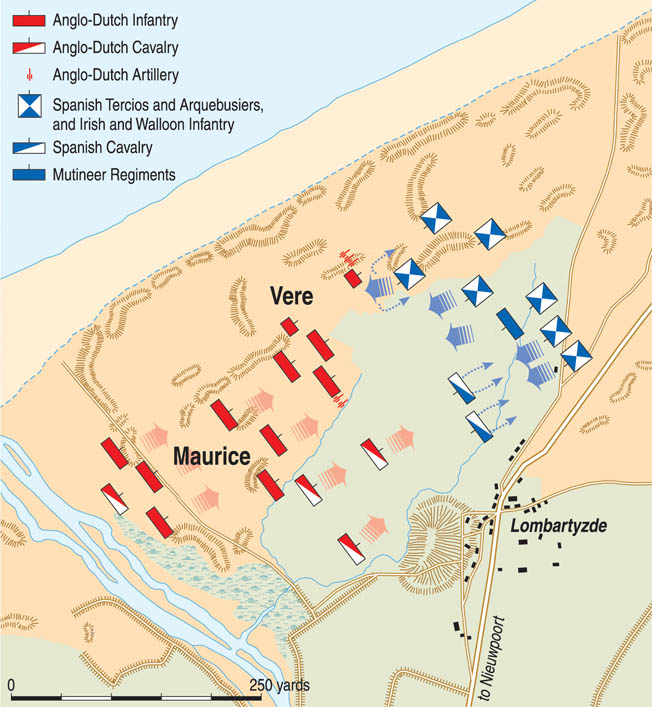

At 2 pm, Maurice ordered the army to turn right and move to the deep sand dunes just off the beach. Albert immediately followed suit. Now, in addition to wind and smoke, the sand from atop the hills began blowing into the faces of the men. The Dutch still had the river to their rear and the incoming ocean on their left. There was, however, a flat grassy meadow to their right, a key area. Its possession by the Spanish would complete a virtual encirclement of the Dutch army.

The Dutch made minor alterations to their battle arrangements after settling into the dunes. Six cannons were left on the beach, and four companies of Frisians joined them to make up the far left flank. There they remained as a safeguard against a flanking movement. By now the beach had shrunk to less than 100 yards. Louis’s cavalry shifted to the meadow on the right, where serious action was certain to take place. Maurice’s greatest strength remained Vere’s forward ranks. Vere carefully arranged his pikemen and musketeers among the dunes to take advantage of the rugged terrain. He placed the last two Dutch cannons atop one of the hills to provide a clear field of fire.

The Dutch Ranks Waver

The battle commenced promptly at 3:30, when Aragon ordered the mutineers forward. Before the opposing front ranks could even engage, Louis of Nassau leapt to the offensive. Observing the idle behavior of the Spanish cavalry opposite his lines, he ordered his horsemen to attack. It was an instant success, at once easing the fear of encirclement. The Spanish cavalry fled without a fight. In the excitement, however, Louis ill-advisedly allowed his cavalry to chase their beaten foes for some distance. The exhausted Dutch pursuers would be unable to return and assist in the critical fighting now beginning among the dunes.

In the center of the battlefield, Aragon’s initial attack on Vere consisted of just 500 arquebusiers probing the Dutch line. The real onslaught occurred moments later. Soon, the advance guards were locked in a vicious push of pike. Believing he could carry the day by sheer force, Albert ordered his four escuadróns to march on the heels of the mutineers. Vere’s English and Frisians had stood their ground effectively against Aragon, but the weight of the additional escuadróns threatened to break their line.

Maurice resolved to match strength with strength, throwing Solms into the growing melee and trusting that the Dutch rate of fire would tell against the mass of escuadróns. The tactics so painstakingly developed by the Nassau cousins over the course of a decade came to bear on the Spanish, allowing the Dutch to relentlessly pour shots into the enemy and hold their ground. But against such overwhelming pressure, resistance could last only so long. Albert ordered his third rank to join battle, forcing the Dutch to fall back. The Dutch second rank fell back into the third, which in turn collided with the supply train and the camp followers huddled behind the army. Luckless civilians, including women and children, fell into the river and drowned.

The Dutch fought hard, but they were clearly faltering. One more Spanish surge could throw them all into the river to drown. Vere fought desperately at the forefront of his beleaguered troops, taking two musket wounds through the same leg. By now the field was a crowded mess. Individual units, including the massive Spanish squares, were becoming indistinguishable.

Dramatically Reversing the Tides of Battle

Having finished his chase, Louis gathered together the remnants of his cavalry and petitioned Maurice for another charge, this time against the main Spanish army. The latter reluctantly gave his consent, but the second charge turned out vastly different than the first. Protected by musket fire, the reorganized Spanish and Italian cavalry threw back the Dutch horse and sent it fleeing. Louis himself barely avoided capture. Even worse, the panicked flight sent shockwaves through the ranks of the Dutch infantry. The English and Frisians, having stood so valiantly, now broke. Vere narrowly eluded death when his dead horse pinned him to the ground and he was pulled out to safety at the last second. The Spanish needed only to coordinate their efforts for one final drive to win the day.

But at this stage of the battle, coordination among the Spanish infantry was nearly impossible; the escuadróns had all but disintegrated. Upon reaching the Dutch cannons placed atop the highest dune, the Spanish advance slackened, providing Maurice with one last chance to turn the battle around. He had only three squadrons of Dutch and English cavalry remaining in reserve. They would have to prove sufficient or all was lost.

At their head, Maurice ordered a charge straight into the Spanish flank. Exhausted from storming the numerous sand hills, the Spanish infantry failed to hold. Maurice and his troops smashed straight through the disorderly ranks, triggering a general panic. At the same time, Dutch cannons opened fire at point-blank range, decimating the enemy’s front ranks. In an instant, the momentum swung inexorably to the Dutch.

Preserving the Dutch Rebellion

Seeing the success of their mounted compatriots, Vere’s Frisian pikemen rallied and counterattacked. They were soon joined by Swiss mercenaries. A second charge by Maurice transformed the battle into a rout. The Spanish army scattered as Vere recaptured the lost hills. Along the way his men discovered a rare prize—the Admiral of Aragon, pinned under his horse like Vere before him. Although wounded himself, Albert was more fortunate. Thanks to the brave efforts of his Irish rear guard, the archduke managed to escape, all the while cursing the cowardice of his Spanish and Italian cavalry, to which he attributed the disaster.

Although the thickest of the fighting was over by 7 pm, the Dutch pursuit continued on until dark. The States-General later criticized Maurice for not mounting a more vigorous chase, but the commander defended himself on account of the army’s exhaustion. In any event, the politicians had little room for complaint. Maurice essentially had rescued them from their own disastrous decision. Some 3,000 Spanish dead and another 600 captured attested to his triumph. Combined with the earlier action at Leffingen, Dutch casualties amounted to 2,700.

The battered Dutch abandoned any thought of marching on Dunkirk and instead headed back for Ostend. From Ostend, the army embarked on ships for the brief journey home. Maurice felt fortunate. Had he failed, the Dutch rebellion would have been crushed. Instead, he had fought the Spanish to an exhausted standstill. An ensuing truce held for the next 12 years and set in motion the ultimate independence of the United Provinces, built on the ever-shifting sands of Nieuwpoort.

Prosaic run through of the years leading up to the battle, but the conclusion is forlorn. The truce came in 1609, and so rather undercuts the implication that Nieuwpoort exhausted the Spanish.

The exhausted Spanish undertook a three year siege of Ostend, and then in 1605 Spinola out thought and out manouevred Maurits to take the war to the eastern frontier, and show the Dutch that the inner provinces were not as safe as they thought [1606].

In 1607 came an armistice, that eventuated in 1609 into the Twelve Year Truce.

If the battle did ‘exhaust’ Spain i wonder what Spinola would have achieved if Spain was not exhausted.