By Neil Cosgrove

Most histories of the American Revolution give the fledgling Patriot navy only one hero: John Paul Jones. While not begrudging Jones’s recognition, it seems unfair to represent the Continental Navy with a single fighting captain. Room should be made for a nearly forgotten hero of the Revolution, Commodore John Barry, who contested British forces on land and sea over almost the entire course of the war.

The son of a Catholic tenant farmer, Barry was born in Ballysampson, County Wexford, Ireland, in 1745, at a time when harsh English penal laws stripped civil liberties from anyone of the Roman Catholic faith. Barry’s family was evicted from their holdings by their absentee landlord and forced to relocate to Rosslare, a seaside village where Barry’s uncle had a fishing skiff. These events combined to produce in Barry a lifelong love of the sea, a passion for liberty, and a hatred of all things English. At the age of 15, Barry left his homeland to serve as a cabin boy on a commercial ship. An industrious and natural-born sailor, within six years he was a captain and commander of his own vessel.

That ship, Barbados, sailed out of what would become Barry’s home port, Philadelphia. The imposing 6-foot, 4-inch, barrel-chested Barry soon developed a reputation for honesty, humility, and good judgment that won him an admirable reputation among the merchant sailing community of Philadelphia. Barry was respected as a strict but fair captain by those who served under him. His final command before the Revolution was the 200-ton Black Prince, a ship that was owned in part by John Nixon, who would be the first person to read the Declaration of Independence to the general public, and Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration and the future “Financier of the Revolution.” Black Prince set the record for the fastest single day’s sailing, logging 237 miles in 24 hours. At the beginning of the Revolution, Black Prince was said to be the finest and most profitable ship in the colonies.

Hearing of hostilities between the colonies and Great Britain while in London, Barry made a swift passage back to Philadelphia and immediately offered his services to the newborn nation. The Continental Congress had recently authorized the purchase of several merchant ships to be converted into warships. One of these was Barry’s own Black Prince, which was renamed Alfred. As its former captain, Barry would have seemed the logical choice to command the rechristened ship, but he was disappointed. The early navy was to be a New England affair, and nepotism triumphed over ability. Three of the first eight captains were related to the Navy Committee chairman, Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island. Even Barry’s fellow Celt and merchant captain, John Paul Jones, was only able to secure a berth as a lieutenant on Alfred through connections with his fellow Masons in Congress.

If Congress did not appreciate Barry’s personal connections, it did recognize his experience. Barry was commissioned, along with master shipbuilder Joshua Humphreys, to oversee the transformation of merchant vessels into the new nation’s first warships. To Humphreys fell the task of increasing the structural integrity and piercing the hull for cannons; to the accomplished sailor Barry went the refitting and re- rigging of the complex network of ropes necessary to improve the speed and handling of ships in combat. Eventually, Congress replaced the New England-dominated Naval Committee with the more representative Marine Committee. One of its first acts was to appoint Barry to command the new 16-gun ship, Lexington. It was a decision Congress would not regret.

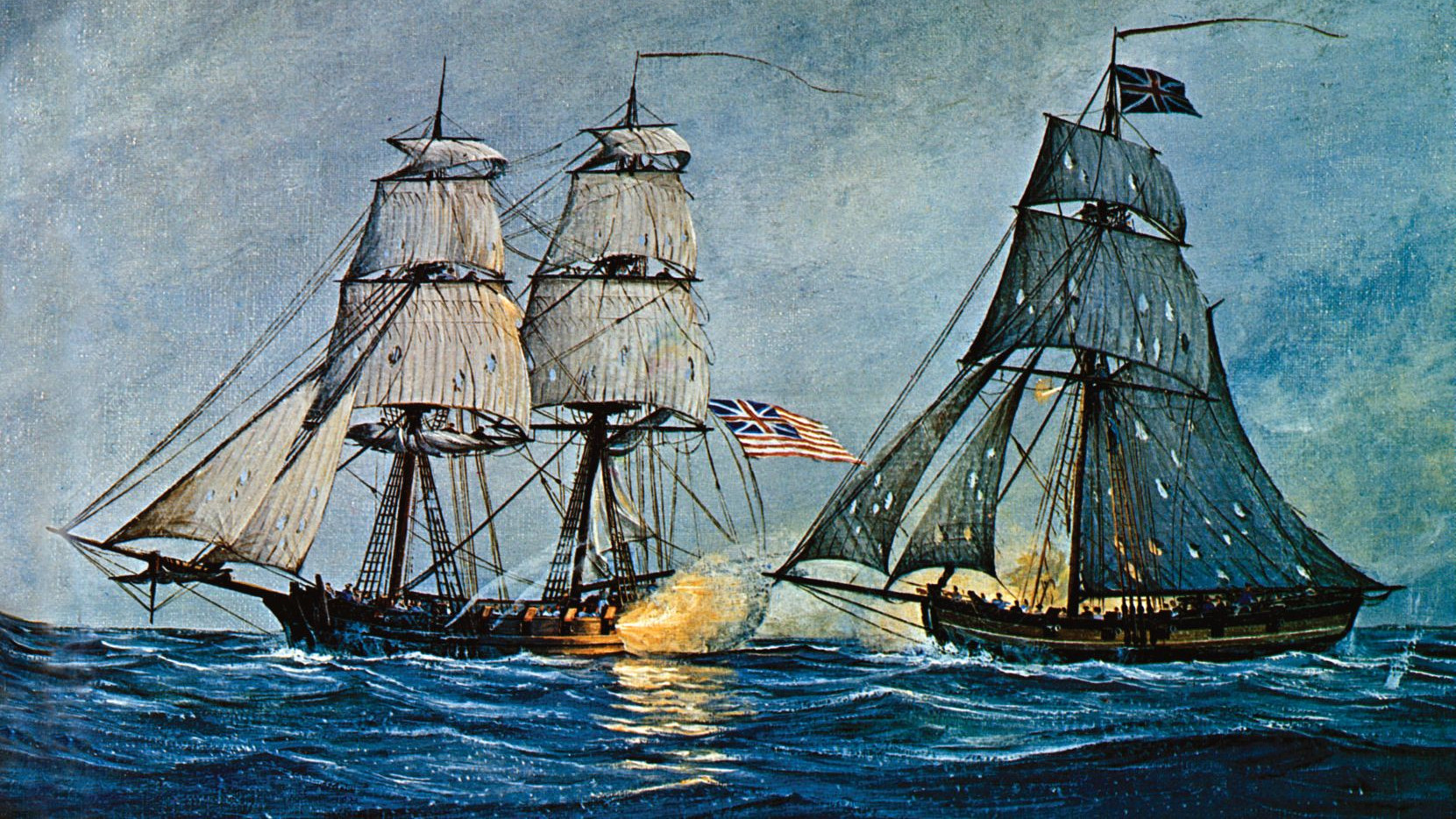

Barry sailed from Philadelphia on March 28, 1776, and was immediately in action. Successfully eluding the formidable British ship Roebuck in Delaware Bay, he made for the open sea. On April 7, Lexington encountered HMS Edward. After a fierce two-hour battle, Barry and Lexington emerged triumphant. As per his character, Barry’s report to Congress was a model of brevity and modesty, preferring to give credit to his crew rather than himself: “I have the pleasure to acquaint you that all our people behaved with much courage.”

The citizens of Philadelphia turned out in celebration to see Edward come into the harbor, the first Royal Navy prize to reach an American port. Even the dour partisan John Adams had to observe of Barry’s victory, “We begin to make some little figure here in the navy way.” Admiration was not confined to the Americans. British Captain Snape Hammond voiced a frustrated admiration of Barry: “The North Side of Delaware Bay is encompassed with shoals and shallow water and this passage Mr. Barry is at present master of. I have chased him several times but can never draw him into the sea.” He would not be the last British captain to be impressed with Barry’s judgment and seamanship.

Barry and Lexington continued playing a dangerous game of cat-and-mouse with superior British ships of the line. On June 12, 1776, Congress directed that 191 captured firearms “sent up by Captain Barry” be used to equip a new battalion. On June 29, the brig Nancy, bringing much-needed supplies to the American rebels, including 386 barrels of precious gunpowder, was pursued by six British warships. Joined by Barry’s Lexington, along with the Continental ships Wasp and Reprisal, Nancy was able to temporarily elude her pursuers in a fog. It was agreed among the captains that Nancy be run aground in an effort to save her precious cargo. All three Continental warships dispatched their boats to unload the cargo, with Barry personally leading efforts to save 268 barrels of the prized gunpowder.

When the fog began to lift, a lookout spotted the pursuing British ships, which were approaching with twice their number to board Nancy. Realizing he was facing insurmountable numbers, Barry ordered that a quantity of loose powder be scattered in the hold with the remaining barrels of powder, while a billet of burning wood wrapped in a sail was placed over the hatchway to act as an improvised fuse. Barry then directed the Continental sailors back to their boats to make good their escape to waiting American warships. Barry’s improvised time bomb had disastrous consequences for the enemy. Just as the British boarded the ship, the fuse reached the powder in the hold. A tremendous explosion ensued; not one of the boarding party escaped. The loss to the British was devastating. Some 40 to 50 sailors were killed, and gold-laced officers’ hats and other equipment washed up on shore for days after the explosion.

Congress rewarded Barry’s success by appointing him to one of the new warships that Congress had commissioned to be built, Effingham, which was still under construction in Philadelphia. The war during the fall and early winter of 1776 was not going well for the Patriot cause, with Washington falling back through New Jersey after the crushing British victories in New York. Barry was not a man to sit idly while his adopted country was in peril. He obtained permission to form an ad hoc naval brigade of sailors, marines, and heavy guns and take them to Washington’s aid. The Continental Marines under Barry’s command subsequently distinguished themselves at the Battle of Trenton. Before returning to Philadelphia, Barry, his sailors, and his marines were given the honor by Washington of conveying wounded prisoners through British lines under a flag of truce and carrying a message to General Cornwallis.

The victories at Trenton and Princeton were short-lived, and dark days lay ahead for the country and for Barry personally. He returned to Philadelphia as the senior commander of that port, but still without a ship—no progress had been made on Effingham in his absence. The British captured Philadelphia in September 1777. Barry and his fellow captain, Thomas Read, were ordered to take the incomplete frigates Effingham and Washington up the Delaware to White Hill while Congress fled to York, Pennsylvania.

During the evacuation, Barry was approached and offered a bribe of £15,000 gold and a command in the Royal Navy if he would desert and turn over Effingham. Barry, in his own words, “spurned the idea of being a traitor” and sent the conveyor of the bribe away. “I have devoted myself to the cause of this country,” said Barry, “and not the value or command of the whole British fleet could seduce me from it.”

Still lacking a seaworthy ship, Barry proposed to the Marine Committee and General Washington that he take the ships’ boats and some barges and harass enemy shipping in the Delaware. Granted approval, Barry took two boats, each armed with a single 4-pounder cannon and carrying 30 men, and slipped past Philadelphia on a cold winter’s night. Washington, now camped at Valley Forge with his suffering army, had simultaneously dispatched General “Mad Anthony” Wayne and 300 men to harass the enemy and capture much-needed supplies.

Barry conveyed Wayne’s men across the river to New Jersey. There, Wayne and his men successfully raided British supply lines, capturing more than 300 head of cattle for the starving troops at Valley Forge. To buy time for Wayne and his men to get their bovine charges to Valley Forge, Barry and his sailors provided a diversion. Barry took his boats up the Mantua River, burning every store of hay they could find. The British turned toward the plumes of smoke, planning to capture the raiders but really allowing Wayne to make good his escape with the captured supplies. In two days, Barry and his men destroyed 400 tons of forage, leaving ashes and embers for the British cavalry and supply horses. At Washington’s request, Barry meticulously noted the names and the quantity of forage destroyed at each farm so that the farmers could be fairly compensated for their losses.

The diversionary raid complete, Barry took his small guerrilla navy into hiding to await fresh opportunities. These weren’t long in coming. On March 7, 1778, Barry received word that two transports and an armed schooner would be passing their position at Bombay Point. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, Barry resolved to attack with 27 men and five rowboats. As the armed transports Kitty and Mermaid passed Barry’s position, he struck. Mermaid surrendered without firing a shot, then Barry’s boarding party attacked Kitty, which also surrendered after exchanging cannon fire.

Quickly securing Kitty’s crew in the hold, Barry took the captured ship straight at the 20-gun armed schooner Alert. In a remarkable bluff, Barry demanded that Alert surrender, promising fair treatment for the officers and their private baggage. Remarkably, Alert stuck her sails, despite its advantages in guns and men. In a single engagement, Barry and his rowboat fleet had captured three British

ships, 116 prisoners, and supplies. Vital intelligence was also captured, including a map of British positions in New York and materials relating to the Hessians in British service. Barry sent the captured supplies, intelligence materials, cheeses, and pickled oysters to General Washington.

Fresh from his triumph on the Delaware, Barry received a favor from an unexpected quarter. The British, as part of their preparations to evacuate Philadelphia, burned Effingham, Washington, and several other vessels. Realizing that Barry was too important an asset to have dry-docked, Congress immediately found him a new command: the 32-gun Raleigh, which anchored in Boston. Barry’s new command was badly in need of repair. Several of her new cannons had burst, and her hull was fouled and damaged. After strenuous efforts, Barry and Raleigh finally sailed from Boston on September 25, 1778.

Not long after leaving Boston, Barry spotted two British warships on the horizon. He gave them a wide berth. At 9:30 the next morning, a lookout spotted the two enemy ships drawing near: the 50-gun Experiment and the 28-gun Unicorn. Raleigh was outgunned by more than 2 to 1. For the rest of the day, Barry led his pursuers on a chase, but the wind started to drop and his pursuers began to make up ground. With night coming, Barry decided to risk an attack. If he could beat back Unicorn, he should be able to outdistance the heavier Experiment.

Barry turned into Unicorn and closed the distance. The frigates exchanged broadsides. On the second exchange, Barry heard a sickening crack; a well-placed shot brought a large section of his topmast crashing to the deck. For six more hours, Raleigh and Unicorn traded blows, with neither yielding to the other. Finally, Unicorn sheared off. Barry made for a small chain of islands off Penobscot Bay, exchanging shots with the still-pursuing Experiment. As Experiment turned to avoid the shallows, Barry andthe wounded Raleigh ran aground. Barry disembarked his crew with the initial thought of defending the island, but the bare rocks were found to be indefensible. Barry had no option but to get his crew back to Boston.

For the next year, Barry shuffled between assignments, leading a fleet of privateers of the Pennsylvania state navy and capturing the 14-gun HMS Harlem without firing a shot. Congress finally found a new ship for Barry, and he was given command of the recently completed 36-gun frigate Alliance, considered the finest ship in the Continental Navy. She was the epitome of a frigate; she could outgun or outrun anything in the Royal Navy. Barry now had a ship worthy of his talents.

Barry set sail in Alliance on February 13, 1781, with the mission of conveying Colonel John Laurens, an officer of Washington’s staff, to France. On March 4, Barry ran across an old acquaintance, HMS Alert, the ship Barry had captured and then abandoned three years earlier. Barry captured Alert as easily the second time as he had the first. Alert was found to have illegally made a prize of a neutral ship, La Buonia Compagnia, belonging to the Republic of Venice. Barry would have been within his rights to claim the Venetian vessel as a prize. Instead, Barry thought it important for the new nation to show its respect for the rights of neutral nations and the freedom of the seas. He released Compagnia and her crew.

Alliance’s return voyage was to be even more eventful. On April 2, Barry captured the British privateers Mars and Minerva. A few days later, Alliance encountered a fierce gale, during which a bolt of lightning struck and split the mainmast and badly burned 15 men. In this depleted state, with two prize crews mounted, several men injured, and his ship badly mauled by fierce weather, Barry fought one of the great actions of the Continental Navy.

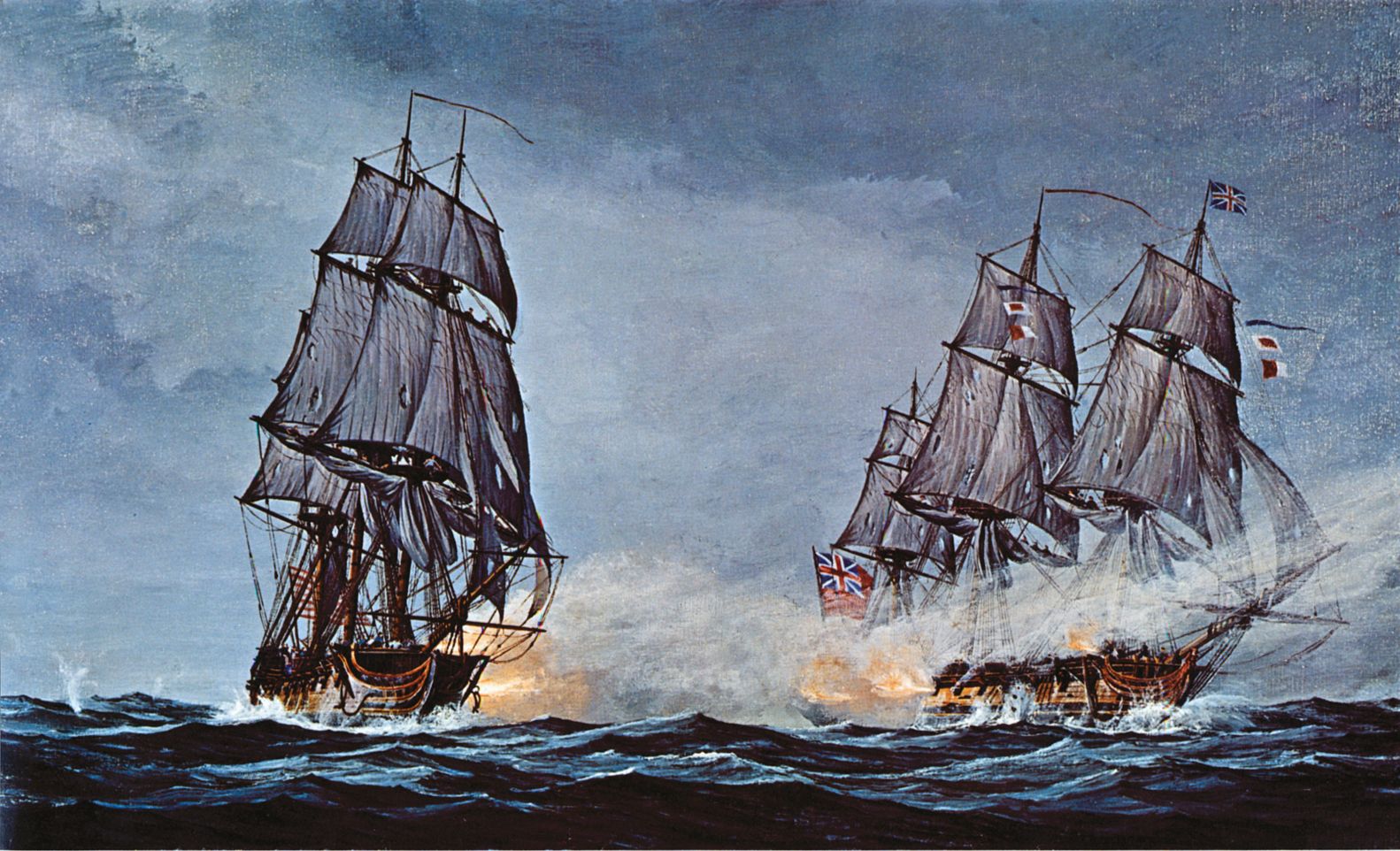

On May 19, Alliance spotted two enemy sails on the horizon, Atalanta and Trepassey. Normally no match for the 36-gun Alliance, the two British ships came upon Alliance after the earlier gales had given way to a dead calm. While Alliance was becalmed, the smaller British ships could use large oars to maneuver. The two British ships took positions on Alliance’s bow and stern. For three hours, Alliance took a pounding while managing to return effective fire on the enemy. While commanding his ship from the quarterdeck, Barry was struck in the shoulder by grapeshot. He continued to exercise command of the ship until loss of blood required that he go to his cabin have his wound dressed.

While Barry was receiving medical attention in his cabin, a shot from one of the British ships tore away Alliance’s ensign, causing the British to think she had struck her colors. Barry’s second in command suggested surrender. “No, sir,” said Barry, “and if the ship cannot be fought without me, I will be brought on deck.” The lieutenant hastily ordered a new ensign to be raised. No sooner had the new Continental ensign gone up than the wind returned, giving Alliance more mobility. Barry immediately poured a broadside into each of the British warships, after which both ships surrendered. Barry had achieved victory in one of the great battles in the history of the U.S. Navy, capturing two enemy warships despite adverse weather conditions, with a ship whose crew was severely depleted.

In a subsequent voyage, Barry captured nine prize vessels, the sale of which netted the Continental Congress some $2.5 million in gold—a record capture for a single cruise. Fittingly enough for the captain who had captured one of the first enemy warships, it would be Barry who fired the last shot in the last sea action of the American Revolution. On the morning of March 10, 1783, Alliance engaged the British warship Sybil for 45 minutes before Sybil broke off the engagement, much the worse for wear. The Treaty of Paris had already been signed; the war was over. Unknowingly, Barry and Alliance had fought and won the last battle of the Revolution.

Barry would continue to serve the new republic for another 20 years. When the United States Navy was formed in 1794, it was to Barry that Washington gave Commission Number One, the commission from which all subsequent U.S. Navy commissions are derived to this day. Although age and the rigors of service took their toll on Barry as a warrior, he was fundamental in establishing the nascent U.S. Navy, supervising the construction of the first frigates built under the Naval Act of March 27, 1794, including his own 44-gun frigate, United States, which served as his flagship.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of Barry’s postwar career was passing on the fighting traditions and spirit he so well represented to midshipmen who learned their craft under his command, including such future American naval heroes as Stephen Decatur, Richard Somers, and Richard Dale. Whenever anyone talks about America’s naval tradition and the great heroes of the Revolution, Irish immigrant John Barry certainly deserves a prominent role in the conversation.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments