By Robert F. Dorr & Douglas L. Carter

When the Boeing B-29 Superfortress crews poured out of the briefing at North Field, Tinian, on the afternoon of March 9, 1945, they were disgruntled. Some were angry.

Sergeant William J. “Reb” Carter, the left blister gunner on a B-29, remembered four words: “Heavy losses are anticipated….” The men had just been told they were going to Tokyo with firebombs—which they had expected. They had also been told what they were not expecting. The B-29 crews would attack at low altitude, at night, without guns or ammunition.

They would be unarmed and exposed over Japan, the destination they called “The Empire.”

Carter’s airplane commander, Captain Dean Fling, was normally a mix of congeniality and stern, businesslike bearing. Today, Fling was abrupt.

“No guns,” said Fling.

“No guns?” someone said. “This cannot be right.”

“It is.”

“There is trouble ahead,” thought Red Carter, who was a gunner but would be carrying no ammunition today.

“LeMay is going to get us killed,” somebody said.

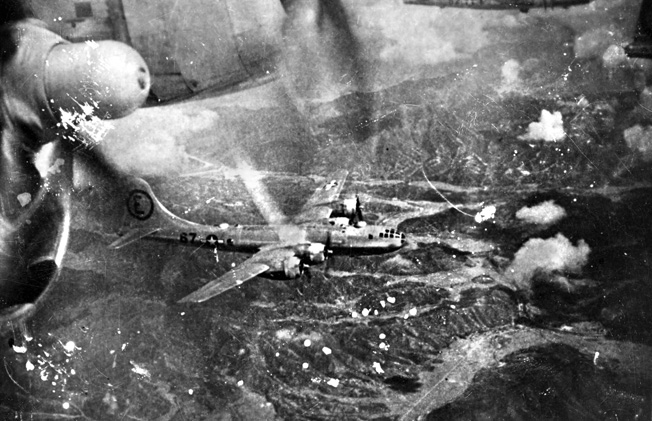

The reference was to Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, commander of the B-29 force arrayed against Japan at airfields on three islands in the Marianas chain in the northwest Pacific, Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. LeMay commanded Twenty-First Bomber Command, which included Carter’s outfit, the 9th Bombardment Group. LeMay’s unprecedented battle order for the day dictated that the bombers would carry no ammunition for their defensive guns. Many B-29 crews in LeMay’s command were going to ignore the order, but the Fling crew in God’s Will was going to follow it to the letter.

Said Carter, “I hope the big brass know something we don’t.”

Until now, bombing mostly by daylight and from high altitude, B-29s had not been having much impact on the Japanese war machine. Swatted around by the jet stream—those furious winds at high altitude that had been undiscovered until the B-29 came along—they had been getting poor bombing results. LeMay had taken over from his predecessor, Maj. Gen. Haywood Hansell, precisely because the B-29 campaign against Japan was not working. Without asking permission, LeMay decided to bring his crews down to low level.

On this day, 334 Superfortresses would take off from Guam, Saipan, and Tinian in early evening. They would arrive over The Empire shortly after midnight.

On tonight’s mission, the primary weapons, 500-pound E-46 chemical incendiary bombs, would rain down on Tokyo like giant firecrackers. Each bomb contained 47 small bomblets, called M69s, strapped together inside a metal cylinder fused to break open at 2,000 or 2,500 feet and to scatter the individual bomblets. Three to five seconds after the big firecrackers hit, they would go off. An explosive charge would violently eject a sack full of gel that would burn intensely. The sack held the gel in one spot, thereby igniting a hotter fire. Other weapons being employed were the E-28 incendiary cluster bomb and the M47, a petroleum-based bomb that would be carried by the lead B-29s.

William Carter’s War

Typical of 4,000 B-29 crewmen heading for Japan on the night of March 9, 1945, William Jesse “Reb” Carter was born in the small town of Omaha, Georgia, delivered by a doctor who arrived at his house in a horse and buggy. Carter’s family moved to Atlanta when he was a child. They were very much people of the Deep South.

As a teenager, the tall, toothy Carter was the local whiz in yo-yo competitions. He was in the 11th grade and was 18, a little old for his level in high school and 10 months older than a distant relative—Jimmy, to the southwest in Plains, who would one day become president—on December 7, 1941.

was the left blister gunner aboard the B-29 bomber nicknamed God’s Will. Carter’s bomber was among those that executed the

devastating firebomb raid on Tokyo on March 9-10, 1945.

That Sunday afternoon, Carter was listening to the family’s favorite afternoon radio show Top Tunes on Atlanta station WATL with his parents, William and Anne, and his 14-year-old brother Pete. Carter was consuming the last of the cake from his birthday party four days previously. The cake’s vanilla icing was a special treat for him.

A few minutes after 2:30 pm Eastern Standard Time, a Mutual Broadcasting System bulletin reported events at a place called Pearl Harbor. “Turn the sound up,” Carter’s mother said.

“This is an outrage.”

Carter looked at his dad, who was an accountant, and saw a furrow in his brow. There was no accounting for what they were hearing now. “The Japanese have attacked us and we are going to be in some kind of war,” the older man said.

He gave his sons a special look. They were a loving family. “I hope this thing won’t last long enough for either of you to be in it.”

“It’s God’s Will“

At North Field, Tinian, following the briefing and a quick, mild, late afternoon thunderstorm so typical of these islands, gunner Reb Carter dismounted from a boxy, 4×4 weapons carrier at the hardstand and started toward a B-29 with his crewmates, including airplane commander Dean Fling.

Carter’s B-29 today was slotted at the cutting edge of the nighttime, low-level air assault being mounted on the Japanese capital. It was scheduled to be the seventh aircraft from their group over target; the first six would carry M47 incendiaries and use their fiery bombloads to mark the “urban area of Meetinghouse,” a code term for Tokyo, for Superfortresses to follow. The rest of the group would follow with larger E-46 bombs.

Carter had no guns to fire if Japanese night fighters found them later tonight, but his role as a scanner, tipping off the flight deck crew about engine operations and events around the aircraft, would never be more important.

Seeing Carter, a member of the line crew who may have been new asked him which plane he was heading for.

“It’s God’s Will,” said Carter.

That was the name of the aircraft. In the night, no one could see the emblem painted on the nose of the bomber, a giant bluish purple shield enclosing a Christian cross bisected by a wide-bladed sword. The name was a nod to the divine intervention that had apparently saved the Fling crew during its first combat mission, but pilot 1st Lt. Harold L. “Pete” Peterson—he sat in the right front seat and would have been called the co-pilot on any other aircraft—had been planning on the name ever since the crew came together in the United States. Instead of pilot and co-pilot, the B-29 had airplane commander and pilot. Peterson was an avid churchgoer.

Cruising Without Formation

Takeoff was frightening for B-29 crewmen, especially those in the rear of the aircraft. Every man on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian had seen a B-29 fail to get skyward, falter, and fall into an unforgiving sea dotted with rock formations. The B-29 remained an imperfect aircraft. Four hundred and two B-29s were lost bombing Japan—147 of them to Japanese flak and fighters and 255 to engine fires, mechanical failures, and takeoff crashes.

God’s Will lifted into the air from Tinian at 6:21 pm that busy Friday evening. Fling, Peterson, Carter, and other crewmembers did not know that theirs would inadvertently become the first B-29 from their group to reach the Japanese coast, yet, because of ensuing confusion, one of the last to drop bombs.

If war is moments of terror interrupted by hours of boredom, the long journey across the ocean to Japan was mostly in the latter category. Tonight, there was no aerial formation. Every one of LeMay’s Superfortresses was on its own, cruising at low level across an open sea. The Dean Fling crew was out there in the night, hugging the dark Pacific, the Japanese home islands approaching. In the left front seat Fling was listening to his navigator and engineer on the interphone and glancing back and forth at Peterson in the right seat. Occasionally, when a minor problem arose, he cussed. Fling was from Windsor, Illinois, and was not as devout as Peterson.

The bombardier aboard God’s Will was 1st Lt. Don “Red” Dwyer. He was using his bombsight to give the navigator drift readings. He took off his headset and chatted with pilots Fling and Peterson.

Reb Carter acted as a scanner, keeping his eyes on the No. 1 and No. 2 engines, ready to utter a warning if a mechanical problem revealed itself.

Searching for Tokyo

As God’s Will neared the halfway point, Carter’s best friend, Sergeant Richard “Bake” Baker, the radar operator, was unable to find the embattled island of Iwo Jima, soon to become an emergency site for B-29s with battle damage, on his six-inch scope.

Navigator 1st Lt. Phillip Pettit had a radar screen identical to Baker’s that was not working, either. The crystal in the radar transmitter that powered both screens was malfunctioning. The radar screens were blank. The only thing Baker or Pettit could see was the illuminated lubber line as it swept around the scope like a second hand of a clock. Nothing else was visible.

Pettit was very junior but was universally respected among the crew. Said Baker, “We had an excellent navigator in Pettit. In addition to our navigator, both pilots and the bombardier had some navigation training. But I was not in any position to help. I didn’t have an air speed indicator. I didn’t have anything on my scope. I was completely blind.”

“Fling taught college physical education before he came into the Army Air Corps so he had a good way with people,” said Baker. Even if a heavy bomber carrying 11 men was going to get lost on its way to The Empire, “Fling would never demonstrate that he was dissatisfied with any one of us in front of anyone else. If we did anything wrong, that was considered a private matter and when no one else was around he would handle it.”

Tokyo “Lit Up Like a Christmas Tree”

“We were the first ship to reach the coast of Japan,” wrote Carter in his forbidden diary, “but we were lost because the radar went out and we were flying in electrical storms.”

A dark mass of land to their left gave way to a yellowish glow of the kind that could come only from electric lights.

“That’s a city,” Carter said over the interphone. “All lit up.”

“I think that’s Tokyo,” said Dwyer from his ringside seat in the nose. “I wonder why they have lights on in the city with us coming to visit them.”

“No,” said Pettit. “It’s Yokohama.”

As if considering, Pettit added, “Surely, Tokyo, the seat of government and the number one military target in all of The Empire isn’t going to be all lit up like a Christmas tree.”

He was wrong.

Incredibly, even as the first pathfinder B-29s were on their final approach, and as a new day began—before the bombs, before the conflagration—street lights in Tokyo were lit. Instead of turning west toward Tokyo, God’s Will mistakenly continued flying north.

They were in the sky, in the night, off the coast of Japan, on a flight where fuel was critical, with no idea where to turn next.

Carter followed a circuitous path to the March 9-10, 1945, great Tokyo firebomb raid. He took basic training in Greensboro, North Carolina. He went to the college training detachment at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, preparing to go into flight training and to become an officer and a pilot.

Carter Gets His Gunner’s Wings

On February 14, 1944, at Duquesne, Carter used his fountain pen and cursive handwriting to draft a letter to his girlfriend, Phyllis Ewing—daughter of a prominent jewelry distributor—whom he had met at a swimming pool one Sunday afternoon in Atlanta. Carter was smitten. He called her his devil, and he began his letter, “My dearest, dearest darling Devil…

“Darling, I don’t see how I could ever get such a beautiful, adorable, darling, sweet girl as you.” Later in the letter, perhaps feeling anxiety—they were not yet engaged—he wrote: “Don’t worry about me quitting loving you because I never will.” Carter wrote that they would see each other when he began pilot training at Maxwell Field, Alabama.

Weeks later, he and his buddies were told that the Army had too many pilots and not enough gunners. Instead of Maxwell, Carter was sent to Tyndall Field, Florida, for “flexible gunnery training.” His train would pass through his hometown. Carter made a long distance telephone call, not an easy thing to do, and told his Dad the time his train would be in Atlanta on the morning of April 16, 1944.

On arrival, Carter’s family and his girlfriend, Phyllis, and her family, were at the station. It is unclear how he pulled it off, but Carter was the only person allowed off the train during the brief stop. He began kissing Phyllis while soldiers leaned out the passenger car windows and began whistling.

After months of intensive gunnery school at Tyndall, Carter earned his gunner’s wings and was transferred to Lincoln Field, Nebraska, for additional training. Meanwhile, across the Pacific the seizure of the Marianas island chain opened the way for B-29s to be based in Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. Three days after Tinian was secured, Carter wrote to Phyllis from Lincoln: “The way I feel, knowing you want to marry me now and love me so much, I could lick the whole Jap Army so don’t worry about me.”

First Flight in a B-29

From Lincoln, Carter traveled to McCook Field, Nebraska, where he saw a B-29 for the first time. At McCook, officers and enlisted men from training bases around the United States came together, formed crews, and pressed ahead with preparations, planning, and training. On August 21, 1944, airplane commander Dean Fling remarked that he liked the looks of the men assigned to him.

Peterson, the right-seat pilot and the most devout among the crew, had been a varsity athlete in college. In flight training, Peterson’s flight instructor was a Hollywood actor—Robert Cummings had been taught to fly by his godfather, Orville Wright.

In addition to Peterson, Fling acquired bombardier Dwyer, navigator Pettit, flight engineer Lawrence Eginton, radio operator Thomas Sulentic, radar operator Baker, central fire control gunner Noah A. “Pappy” Wyatt, left blister gunner Carter, right blister gunner John Emershaw, and tail gunner Norman “Shorty” Fortin.

The Fling crew was assigned to the 1st Squadron, 9th Bombardment Group. Baker wrote that Carter, the only Southerner in the crew, was “friendly as a cocker spaniel” and “did not have an enemy in the world.”

Baker noticed that Carter was confident and thorough, whether handling his machine guns or cleaning their barracks living area or pulling the much disliked kitchen police, or KP, duty that helped keep the troops fed. The Fling crew completed a grueling training flight to Cuba. Now, their awareness grew that they would be taking their B-29 to the western Pacific. They were heading for the real thing.

The First B-29 Landing on Iwo Jima

On January 21, 1945, the Fling crew landed at North Field, Tinian, completing the marathon journey from the United States. The men left McCook in their B-29 and paused at Herrington, Kansas. Their subsequent stops in New Mexico and at Mather Field, California, were typical of the long, winding path from the training grounds of the American Plains to the war zone of the Pacific. The Fling crew proceeded to Hawaii and onward to Kwajalein, and finally Tinian, 38 square miles of coral rock, dust, jungle, and cane fields, crowded with B-29 hardstands, tents, Quonset huts, and docks. It lay 125 miles northeast of Guam and just three miles southwest of Saipan.

The men slept in large tents, each housing the enlisted members of two B-29 crews. They slept on cots on a crushed coral floor.

While LeMay’s plan for the great Tokyo firebomb mission was taking shape, the Fling crew flew its fourth mission, traveling to Tokyo on March 4, 1945, the old-fashioned way, taking off before dawn for a daylight, high-altitude strike. In the dark early morning hours flying toward The Empire, Carter snuggled up in the padded tunnel over the bomb bay and caught four hours of sleep.

Over the target, serious trouble befell Dinah Might, a B-29 commanded by 1st Lt. Raymond F. “Fred” Malo, not because of Japanese gunfire but because of mechanical problems common with the Superfortress.

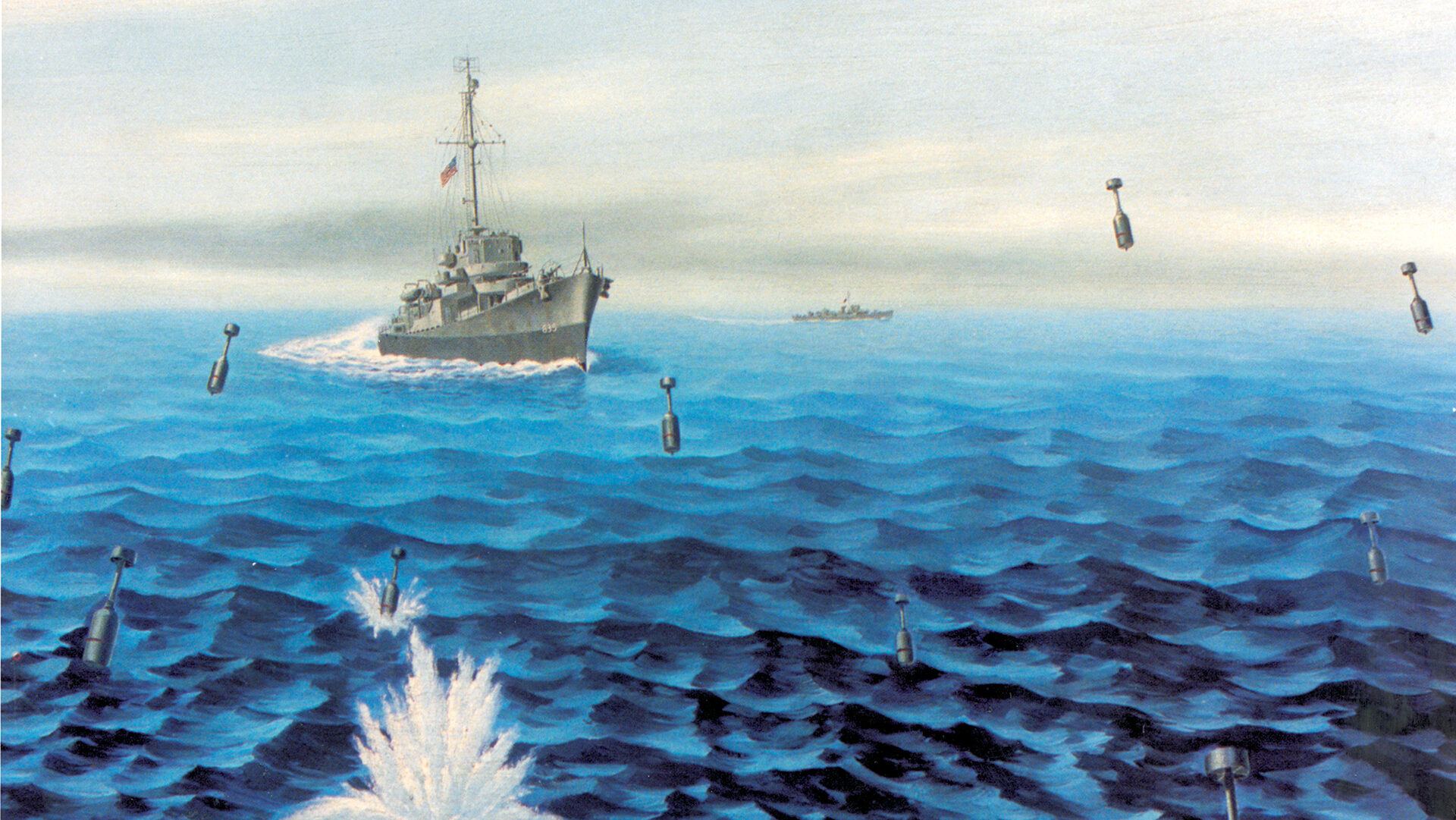

Fling announced on the interphone that God’s Will would escort Dinah Might as it attempted to get home. Wrote Carter: “We led Malo’s ship to Iwo Jima. Malo’s bomb bay doors were stuck in the ‘open’ position, the fuel transfer was out and the radar was out.”

Iwo Jima was within reach, but bitter fighting was taking place there. No B-29 had yet saved itself by landing on the sulfur island being slowly wrested from the Japanese at a cost of 6,800 Marine lives. But with Fling riding herd and Carter watching, Malo did land on Iwo, the very first of 2,251 landings by B-29s that saved crewmembers’ lives and redeemed the awful cost of the battle for Iwo Jima.

Finding Choshi Point?

While the Fling crew got lost at the start of the great Tokyo firebomb mission, Carter mulled over four words that had been uttered at the briefing: “Heavy losses are anticipated.”

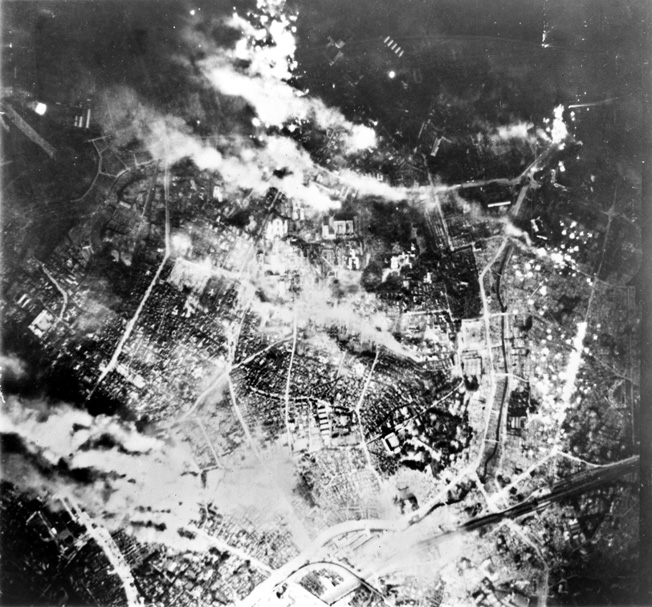

At the start of the attack, around midnight, pathfinder B-29s dropped heavy incendiaries to mark the target area of the city with a burning X.

When this narrative was written 67 years after the war, fully five members of the God’s Will crew were alive and articulate. All agreed that they saw the streetlights of the Japanese capital before the pathfinders set the city afire, misunderstood what they were seeing, and continued north. They flew over open water paralleling the coast away from their intended run-in location at Choshi Point.

They “expended extra fuel in searching for the target,” an official report would later say. Their B-29 strayed from clear, windy Tokyo to shrouded, snow-spattered skies above open water just off the coast north of the capital. Had they been a few miles inland, they might have been in the same location where three other B-29s, caught in a more intense part of the same snowstorm, flew into the same mountain at the same time—32 crewmembers killed in a matter of seconds.

God’s Will was burning precious gas and was lost. Carter had long since become accustomed to the drone of the R-3350 engines in his ears. He peered from his blister trying to discern some distinctive feature, any distinctive feature, in the early morning darkness.

Over Tokyo, silvery B-29s continued to pass through searchlight beams, incendiary bombs continued to tumble from their bays, and the city burned with such intensity that flyers could smell roasting flesh. Aboard God’s Will, navigator Pettit and radar operator Baker struggled to get their radar screens to work. Pettit made no attempt at celestial navigation because of poor visibility in a sky now filled with snow. The radar flickered on intermittently. Pettit told Fling that he was seeing Choshi Point on his scope.

He was wrong.

Retracing Their Steps

Fling made a 90-degree left turn to head to the west toward Tokyo. God’s Will made landfall over the Japanese home islands for the first time. About 15 minutes later, Dwyer, looking down from his perch in the nose, saw a mountain covered with snow. Right-seat pilot Peterson saw it too.

“There’s a snow-capped peak right below us,” Dwyer said over the interphone.

“There’s not supposed to be a mountain there,” Fling said. There was no mountain near Choshi Point.

Dwyer would later say that God’s Will came close to slamming into the mountainside. Fling threw the aircraft into an abrupt, climbing 180-degree turn. He pointed the bomber’s nose back toward the ocean from which they had just come.

They retraced their route. The radar went on the blink again.

Weary from struggling to get into the right place, the Fling crew was skirting the Japanese coast north and east of Tokyo.

By now, more than 200 B-29s had passed over Tokyo. One was blown out of the sky right over the Imperial Palace, but the heavy losses that had been predicted were not taking place.

Three Hours off Schedule

The crew of God’s Will had been lost for an extraordinary, fuel-guzzling 21/4 hours, had nearly slammed into a mountain, and were seething with frustration and anxiety. It was less than a week after Malo’s first ever B-29 landing on Iwo Jima, and crews had been briefed that if they couldn’t get home, they should try for Iwo.

Fling’s men were determined to carry out the mission even though, as Carter noted in his journal, “We knew we wouldn’t make it back to base because we were low on gas.”

When God’s Will belatedly stumbled upon Tokyo, as many other B-29s were doing in the confusion of the night, Carter thought of it as deliverance. “We were 80 miles away when we saw the fire,” he wrote. The bombing had been going on for two hours.

When God’s Will entered the final swarm of B-29s approaching Tokyo, Carter heard the sounds of other aircraft and of gunfire. He saw the searchlights, the flak bursts, the burning urban sprawl rushing toward him. Carter wrote in his journal that the flak was “intense and rather accurate” and that “about 100 searchlights” were stalking the B-29s.

God’s Will, far later than anyone ever intended, began its bomb run. Fling turned the aircraft over to bombardier Dwyer.

God’s Will was now flying parallel to B-29s from a different group, braving the heat thermals with Dwyer hunched over his Norden bombsight, trying to ignore the spectacular view of a world afire.

In the final moment of the bomb run, Carter peered out and saw a falling bomb. It had come from a B-29 above them. He estimated that it missed the left wingtip of God’s Will by just 10 feet. Dwyer said, “Bombs away.” It was 3:01 am and God’s Will was almost three hours behind schedule.

Every member of the Fling crew knew that God’s Will did not have enough fuel to return to Tinian. They hoped they could make embattled Iwo Jima. When God’s Will approached Iwo, the sun had become bright, flying conditions were as good as they would ever get in this weather-racked corner of the world, and Iwo’s Motoyama No. 1 airfield looked almost red in its brightness. God’s Will touched down on Iwo at 10:30 am.

Dwyer recalled, “Bullets were flying around us” as Fling taxied God’s Will to a halt in front of a cluster of Marines.

God’s Will—although it sustained two shrapnel holes in a wing—was capable, once it could be refueled, of flying its crew home. Carter noted when they took off that the Japanese were firing small arms at them as they accelerated down the runway.

The Most Destructive Bombing in History

The great Tokyo firebomb mission ignited the hottest fires that ever burned on the earth and killed more people—possibly 100,000; the exact number will never be known—than both subsequent atomic bombs. It was the most destructive bombing attack in history.

Losses on the great Tokyo firebomb mission of March 9-10, 1945, were 14 B-29s, including the three that flew into a mountain together, three that ditched, and one that simply vanished.

The Tokyo fire raid marked the beginning of what became known as the fire blitz. The Fling crew did not participate in the first blitz after Tokyo to Nagoya on March 11-12, but it did fly the remaining three blitz missions against Osaka, Kobe, and Nagoya.

Of the Kobe mission, Carter noted: “The fire looked even bigger than the Tokyo fire to me. An area with a diameter of about 30 miles over the target was as bright as day but it had a reddish color. The sky was full of B-29s, Jap fighters, phosphorus flak, shrapnel flak, rockets, tracers and the blackest smoke I have ever seen. It was enough to scare the devil.”

Flying Through Flak over Nagoya

The fifth and final mission in the great fire blitz took B-29s to Nagoya again on March 19. Now, stocks of firebombs were so low that many Superfortresses carried explosive bombs. God’s Will, which carried incendiaries, was caught in 15 searchlights for six minutes. Fortunately for the Fling crew, another B-29 going over at the same time was caught in 25 to 30 searchlights and received most of the flak. Carter wrote that the other B-29 “flew right thru it but I don’t see how.”

The blitz involved 1,595 sorties and used 9,373 tons of bombs to burn about 32 square miles in four cities. Air Forces commander General Henry “Hap” Arnold sent a message to Twenty-First Bomber Command, saying that the blitz was “a significant example of what the Jap can expect in the future. Good luck and good bombing.”

Japan’s Lt. Gen. Noboru Tazoe, a key air defense leader, said that as a result of the fire blitz he knew, finally, that Japan could not win the war. Thanks to LeMay’s risky decision to fly low and light, B-29 Superfortress crews were finally accomplishing something.

27 Combat Missions

Major George Bertagnoli took over God’s Will when Fling was made group assistant operations officer. The crew became the first from the 9th Bombardment Group selected for “rest camp” in Hawaii because the men had flown more combat missions than any other crew. When they returned to Tinian, they learned that the Malo crew from their squadron, which had made the first B-29 landing on Iwo Jima, was lost in combat over Kawasaki on April 16, 1945. One month later, Captain Samuel N. Slater became the crew’s navigator when Pettit was moved up to group headquarters.

Carter completed 27 combat missions, including another mission to Kobe on June 6, 1945, during which a swarm of attacking fighters wounded Bertagnoli, Peterson, and Dwyer and shot out two engines and damaged a third, prompting another emergency landing on Iwo Jima. The Bertagnoli crew was credited with three Japanese aircraft shot down plus two probables.

God’s Will‘s Rebellious Fly-Over

When General Douglas MacArthur oversaw the formal Japanese surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sunday, September 2, 1945, a 2,400-aircraft flyover was supposed to be part of the event. The weather near Tokyo was poor, so the start of the flyover was delayed.

The Japanese signed first. Observers looked around for the planned flyover and saw no sign of it. The delay was causing some irritation on the part of those orchestrating the ceremony. After the Japanese finished, MacArthur began signing.

Columbia correspondent Webley Edwards was providing a real-time radio narrative. “General MacArthur is using a fifth pen,” Edwards spoke into his microphone. “And here comes one of the big B-29s which I suppose is the leader of the flight which was to put on a demonstration of air power here over the bay this morning.”

But it was not. Although his plane was not part of the planned flyover, B-29 commander Bertagnoli was going to fly over the ceremony whether LeMay, MacArthur, or anyone else liked it or not. Bertagnoli was a “really good man,” Carter said, but he had a rebellious streak, too. Before the planned aerial formation could arrive, Bertagnoli detoured from an assigned supply flight to a different location and, without permission, set his B-29 up for a straight, flat run over the moored Missouri.

Bertagnoli, Carter, and the God’s Will crew—in a different aircraft that day—looked down from their B-29 and saw MacArthur sitting at the signing table on the ship’s deck. The Edwards broadcast was playing on the plane’s interphone. They heard Edwards say, “Here comes one of the big B-29s” and then they heard the sound of their own engines in their earphones, conveyed by the broadcast.

As the Bertagnoli crew flew overhead, Edwards continued. “The weather is miserable for a demonstration of air power. The maximum ceiling is not more than fifteen hundred feet, but everything is going to plan. General MacArthur has finished signing. Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainright and General Percival have saluted him and MacArthur is back to the microphone….”

The scheduled flyover began soon afterward. The war had ended.

William Carter Returns Home

William J. “Reb” Carter (December 3, 1923-November 3, 2011), known as Bill to everyone except his military buddies, received the Distinguished Flying Cross and other awards. He was discharged as a staff sergeant on November 28, 1945. He returned to Atlanta and became a successful certified public accountant. On December 19, 1946, he wed Phyllis Ewing in a simple ceremony at her pastor’s home. They raised two sons, Doug and Gary, and many dogs.

Robert F. Dorr is an Air Force veteran, a retired U.S. diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, a look at presidential aircraft and air travel. Douglas L. Carter is the son of the subject of this story.

I’m trying to find a pic of the b-29 bomber sight what the actual scope looked liked with nothing underneath it so I can read all the numbers not sure if you can help me with that ?

Thanks Matt