By William E. Welsh

Robert Devereux, the third Earl of Essex, was on his way to church in the small village of Kineton in Warwickshire on the morning of October 23, 1642, when he received word that the enemy was at hand. Royalist cavalry had been spotted that morning riding back and forth atop Edgehill, a ridge that dominated the surrounding countryside and lay astride Essex’s supply route to London. Placing Parliament’s cause against King Charles I above his religious devotion, Essex ordered his forces to concentrate immediately at Kineton.

The sun had finally broken through the clouds after weeks of interminable rainfall had slowed the eastward march of both armies in their race east toward London. Essex rode out to scout the terrain himself. A competent commander with a face as round as a gold sovereign and a Vandyke beard and moustache that made him look more like a shrewd merchant than a professional soldier, Essex had extensive military experience both in England and on the Continent. Viewed by many of his fellow officers as ill-tempered, he nevertheless was well-liked by the common men he led.

At the base of Edgehill on its western side lay a great meadow, devoid of trees, known as the Vale of the Red Horse. With a sweep of his eye, Essex took in the low-lying ground, noting the location of streams, hedges, and small patches of farmland. Fortunately for his army, a half mile opposite Edgehill was a small rise. It was on that knoll that his army would await the king’s assembled wrath. Satisfied that he had chosen a good position, Essex ordered his cannons to open fire at 2 pm to induce the Royalists to attack. Long-range guns atop Edgehill barked an immediate response, but their solid shot had little effect as they dropped harmlessly into the soft earth of a cultivated field in front of Essex’s position. It seemed that Essex had chosen his ground well. The first major battle in the English Civil War had begun.

King vs Parliament

With its roots in the monarchy of James I, the war came to a head over the question of whether the king or Parliament was the real sovereign of the English people. Charles’s father, James I, had clashed repeatedly over the matter with Parliament during his 22-year reign. Like his father before him, Charles insisted that the English sovereign ruled by divine right, while Parliament asserted that it was the final arbiter on domestic and foreign policies. When Charles assumed the throne in 1625, he proved even more unwilling than his father to compromise with Parliament on volatile matters related to religion and taxes.

Unfortunately for Charles, the lack of a standing army meant that he did not have a strong body with which to enforce his will. After disbanding Parliament for the third time in 1629, Charles sought to rule alone without either its approval or support. But he made a grave error by trying to impose English-style prayer books on the Presbyterian Church of Scotland in 1639. Urban riots soon gave way to open rebellion, and Charles’s armies were defeated in the First and Second Bishops’ Wars. When the victorious Scots overran and occupied northern England, Charles was left with no other recourse than to call on Parliament to pay an indemnity to the Scots.

The more radical members of Parliament moved immediately to destroy the man they considered to be nothing more than a despot. Charles’s nemesis, John Pym, led Parliament in issuing the Grand Remonstrance, which called for immediate religious reform as well as control over the army and all royal appointments. Unwilling to consider such measures, Charles stormed into Parliament on January 4, 1642, with a large body of armed men in an unsuccessful attempt to seize Pym and four other key leaders of the opposition. The members, who had been alerted that the king was on his way, avoided arrest by slipping out before he arrived. Infuriated by the king’s breach of privilege, his opponents introduced measures giving Parliament control of the armed forces. Sensing that he and his family were in personal danger by remaining in London, Charles fled the city on January 10 for York, where he reestablished his court.

Parliament’s Unparalleled Power

From the beginning of the conflict, Parliament had a decisive advantage in both manpower and resources. London and most of the other major cities in the realm declared their support for Parliament, and in July the fleet pledged its allegiance to Parliament as well. This gave the Parliamentarians, or Roundheads as they were called because of their short-cropped hair, control of most of the major arsenals of the land, including the Tower of London, as well as access to weapons and ammunition arriving from overseas. In the following months Parliament assembled an army from the populous counties of the southeast where it had substantial support, while Charles recruited from the less- populated areas in the north and west of England.

In June, Charles issued commissions to the gentry and authorities in each county to recruit men to his cause. He shifted his base to Nottingham, where on August 22 he raised his standard in a formal ceremony held on a stark hill in the shadow of the historic old castle. By September, Charles had raised five regiments of foot soldiers and about 500 horsemen from the surrounding counties. To further increase his numbers, he marched this force west to Shrewsbury on the Welsh border. The small army arrived on September 20 and continued drilling as additional recruits arrived in camp from the towns and villages of the Midlands and North Wales.

While Charles was en route to Nottingham, Essex left London for Northampton, where he reviewed Parliament’s main army at Dunsmore Heath on September 14. The Lord General, as he was known, left Northampton five days later for Worcester in an effort to keep himself between the king and London. On September 23, Royalist cavalry under the king’s nephew, Crown Prince Rupert of Germany, defeated the Parliamentary cavalry in a sharp clash at Powick Bridge south of Worcester.

Charles left Shrewsbury on October 12 at the head of an army with a 20-gun artillery train. Although some of his generals favored attacking Essex at Worcester, the king preferred an advance on London, where the terrain was more open and Rupert’s cavalry would be able to operate to maximum effect. Essex remained stationary at Worcester for an entire week before he realized that the king was closer to London than he was.

The Royalist Position on Edgehill

Essex set out for Warwick on October 19, trailing a 29-gun artillery train. Neither army traveled more than 10 miles a day. A shortage of tents forced men and officers from both armies to search for billets in the towns and villages along the way. The artillery trains, which neither army allowed to separate from the main column for fear they would be captured, slowed their advance considerably, and heavy rains turned the roads into muck. “Before I had marched one mile I was wet to the skin,” wrote Lord Wharton, a colonel in the Parliamentary cavalry. “The rain continued the whole day, and the way was so base that we went up to the ankles in thick clay.”

The king essentially had stolen a march on Essex. His location at Kenilworth put him within a short distance of the town. But rather than occupying Warwick, Charles ordered his troops to continue marching southeast toward Banbury, where the king planned to force the surrender of the town’s Parliamentary garrison. By October 21 the Royalists, who were called Cavaliers for their lifelong experience in hunting and riding, were a short distance north of Edgehill, at Southam, and closing rapidly on their objective.

Essex was completely unaware of the location of the king’s army. His cavalry, which clung to the main body of the army after its defeat at Powick Bridge, was no help in locating the enemy. Essex directed his army across the Avon River at Stratford-Upon-Avon and Evesham, with instructions to concentrate at Kineton. The following night a group of quartermasters from Essex’s army ran headlong into some of their counterparts in the king’s army at the village of Wormleighton, where both were seeking shelter for the night.

Charles learned around midnight on October 22 that his soldiers had made contact with the enemy. The Royalist horse began taking up positions on Edgehill at 10 am the following morning. The king held a council of war during which he and his generals, after some discussion, decided to attack the Roundheads. Sixty-year-old Robert Bertie, Earl of Lindsey, a veteran with four decades of military experience, quarreled with Prince Rupert over the best tactics to employ in the coming battle. Lindsey favored the heavier Dutch style with which he and his soldiers were most familiar, while Rupert favored the more maneuverable Swedish style crafted by the late King Gustavus Adolphus.

Upon Rupert’s arrival in England, Charles had given him control of the cavalry with instructions to report to the king himself. The idea of Rupert having an independent command did not sit well with Lindsey. When the king agreed on the day of battle to follow Rupert’s advice and use Swedish tactics in the pending battle, Lindsey resigned his post in disgust and walked off to take command of his own regiment from Lincolnshire. The king subsequently appointed Patrick Ruthven, Earl of Forth, to replace Lindsey. A 69-year-old Scottish professional soldier (and a heavy drinker), Ruthven had no more than nominal command of the army that day. By forcing Lindsey to step down, Rupert had cleared the way to lead the army into battle himself.

The Army of Essex

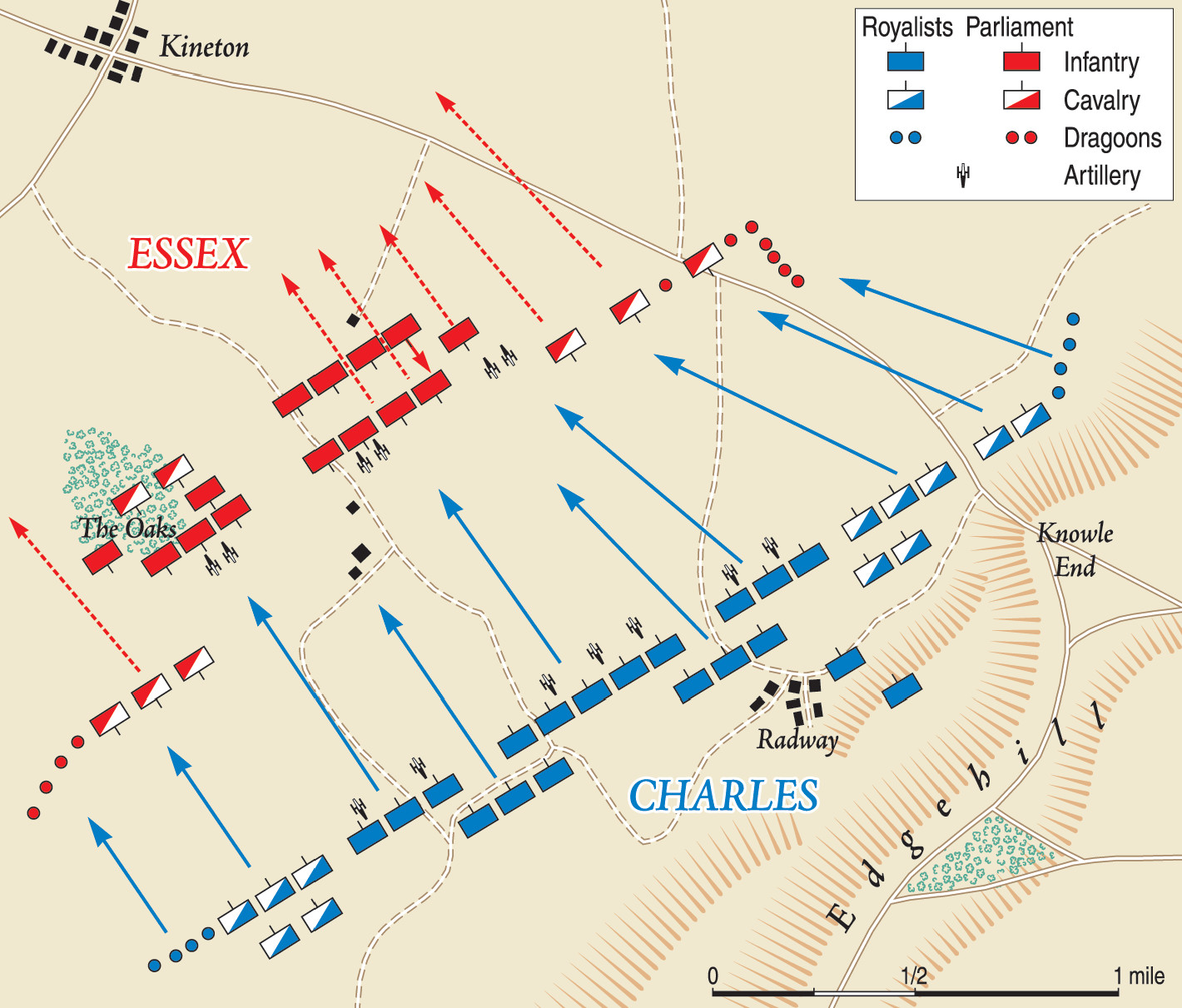

While the Royalists were debating their tactics, Essex and his officers were moving their men into defensive positions to defend against a Royalist attack. Because some of his troops were garrisoning nearby strongpoints in the region, not all of Essex’s troops would arrive in time to participate in the battle. Even so, Essex managed to field about 15,000 men to face the enemy.

His 12,000 foot soldiers were organized into three large brigades. For his front line, Essex placed Sir John Meldrum’s brigade on the right and Charles Essex’s brigade on the left. He placed Thomas Ballard’s brigade directly behind Essex in the second line. In keeping with the Dutch style of tactics, the infantry stood in files eight rows deep. Sir James Ramsey commanded six cavalry regiments on the left wing. The Roundheads, correctly deducing that the opening attack would come from the Cavaliers’ right wing, the position of honor on the battlefield, placed two-thirds of their heavy cavalry on their left under Ramsey. The cavalry formed up in files six deep. To boost his firepower, Ramsey borrowed 700 musketeers from Ballard’s brigade. He positioned 400 men from Colonel Denzil Holles’s regiment behind a hedge at a right angle to his main line and another 300 from Ballard’s own regiment at intervals amid his first line of cavalry.

On the Parliamentary left wing, Essex positioned two regiments of dragoons in marshy ground along a stream that ran perpendicular to his line of battle, with Lord Basil Fielding’s horse regiment behind them. Two other horse regiments, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sir William Balfour and Sir Philip Stapleton, initially drew up on the left, but when the battle began they redeployed behind the Parliamentary foot. Although nominally under the Earl of Bedford, Balfour assumed overall command of the horse on the Parliamentary right wing. The Roundheads deployed 16 of their 29 artillery pieces to support their army.

The Royalists’ Order of Battle

The Royalists descended Edgehill around 1 pm. They numbered slightly more than 14,000 men in all. The Royalist infantry brigades, which totaled about 11,000 men altogether, deployed in two lines. In the front line, from left to right, were the brigades of Henry Wentworth, Richard Fielding, and Charles Gerard, while in the second line were the brigades of Sir Nicholas Byron and John Belasyse. Byron’s brigade not only contained Lindsey’s unit (the Lord General’s Regiment), but also was home to the Royalist’s main battle flag was situated. Sir Edmund Verney, knight marshal of the king’s palace, would carry the royal banner into battle.

As soon as the cavalry advanced, the 11,000-strong Royalist infantry would move across the open ground. In contrast with the well-armed Roundheads, who controlled England’s largest arsenals, many of the Royalist foot soldiers were armed with inferior weapons. A number of the Cavalier musketeers had outdated guns, and several hundred of the Cavalier pikemen were armed only with cudgels.

The Royalist cavalry was charged with clearing the enemy flanks. Rupert, who had about 1,700 men, deployed on the right flank. His frontline units, left to right, were Prince Maurice’s regiment, Rupert’s own regiment, and the Prince of Wales’s regiment. Sir John Byron’s horse regiment was placed behind the front line as a reserve. One troop of the King’s Life Guard was in the front line with Rupert, the other was in the reserve with Byron. The job of clearing the musketeers from the hedges before Rupert’s wing advanced fell to Colonel James Usher’s 500-man-strong regiment of dragoons.

On the Royalist left flank, Lord Wilmot, who had extensive experience fighting alongside the Dutch against the Spanish, led a force of 1,055 men. Sir Arthur Ashton commanded the dragoons assigned to that flank. To supplement their attack, the Royalists deployed 14 light field pieces in front of the infantry and six heavy guns in a battery atop Bullet Hill, on the north end of Edgehill. The king’s personal safety and that of his two sons, 9-year-old James and 12-year-old Charles, rested squarely on the shoulders of a small bodyguard of 50 men known as the Gentlemen Pensioners stationed behind Rupert.

“Matters Are Now to Be Declared With Swords, Not Words”

Led by a rider bearing a brilliant red cornet, Charles and his entourage rode down the line to offer words of encouragement to each horse and foot brigade. In lofty language, Charles told each unit, “Matters are now to be declared with swords, not words.” Showing more courage than wisdom, Charles wanted to personally lead the troops into battle. Since his death would have immediately ended the war, his advisers persuaded him against doing so and removed him to the relative safety of Bullet Hill.

The largely ineffective artillery duel, which began about 2 pm, lasted for an hour before Rupert gave the signal for his cavalry to attack. Usher’s dragoons engaged the Roundhead muskets poised to enfilade the attack. The dragoons, armed with muskets, did not fight on horseback like heavy cavalry, but instead used their horses to maneuver and fought dismounted. They worked in small groups, often trading point-blank fire with the enemy. Rupert rode to each of his brigades and instructed them to advance with their swords drawn, in the Swedish style, and to refrain from using their pistols until they were among the enemy.

A trumpet sounded the attack at 3 pm. The cavalry advanced at a measured pace, the troopers packed so tightly that their boots were almost touching. In the front ranks rode the best-equipped troopers, outfitted with helmet, breast, and back plates, and armed with flintlock pistols, swords, and poleaxes. As Rupert’s horsemen drew closer to the enemy, a second trumpet sounded, and the riders increased their pace from a trot to a canter. They slammed into the front rank of the enemy formation.

Sir Faithful’s Betrayal

As the Royalists neared, a group of Parliamentarian cavalry abruptly switched sides. The troopers belonged to the command of Sir Faithful Fortesque, an odd name for one whose loyalty was so changeable. The unit had been raised before the war to suppress the Irish rebellion, but once war broke out it was incorporated into the Parliamentary army. Fortesque, who harbored serious reservations about fighting against the king, sent word to Rupert through a trusted subordinate requesting that the Cavaliers refrain from attacking his men. When the Royalist cavalry had crossed halfway toward its objective, Fortesque fired his pistol into the ground as a signal to his men to ride forward and join the Royalists. The development unnerved some of the Parliamentary horsemen, who witnessed a group of their comrades switching sides in the heat of battle.

Ramsey’s cavalry, shaken by Fortesque’s betrayal and by its previous unhappy encounter with the Royalists at Powick Bridge, wavered once the Cavaliers were among them swinging their swords and firing their pistols at point-blank range. Ramsey’s men managed one pistol volley at the Cavaliers as they approached and another as they closed, but neither their fire nor that of the remaining musketeers interspersed among Ramsey’s front rank offset the damage inflicted by Rupert’s cuirassiers. A large number of Ramsey’s men fled immediately once the Cavalier tide crashed into them, but a small minority stayed and fought until it became obvious that they would be killed or captured if they stayed. “Our left wing, upon the second firing, fled basely,” scorned Reverend Steven Marshall, chaplain for the Lord General’s Regiment of Foot.

The blow struck by Rupert had a devastating effect on the entire left wing of the Parliamentary army. Holles’s regiment of Ballard’s brigade was closest to the rout of Balfour’s horse regiments. Seeing his musketeers running for their lives, Holles strode defiantly into the swirling mass of men and horses and tried to rally the horsemen. In response to his efforts, three troops of Roundhead horse rallied long enough to allow the musketeers to take shelter behind the pikes.

The Lost Momentum of the Cavaliers

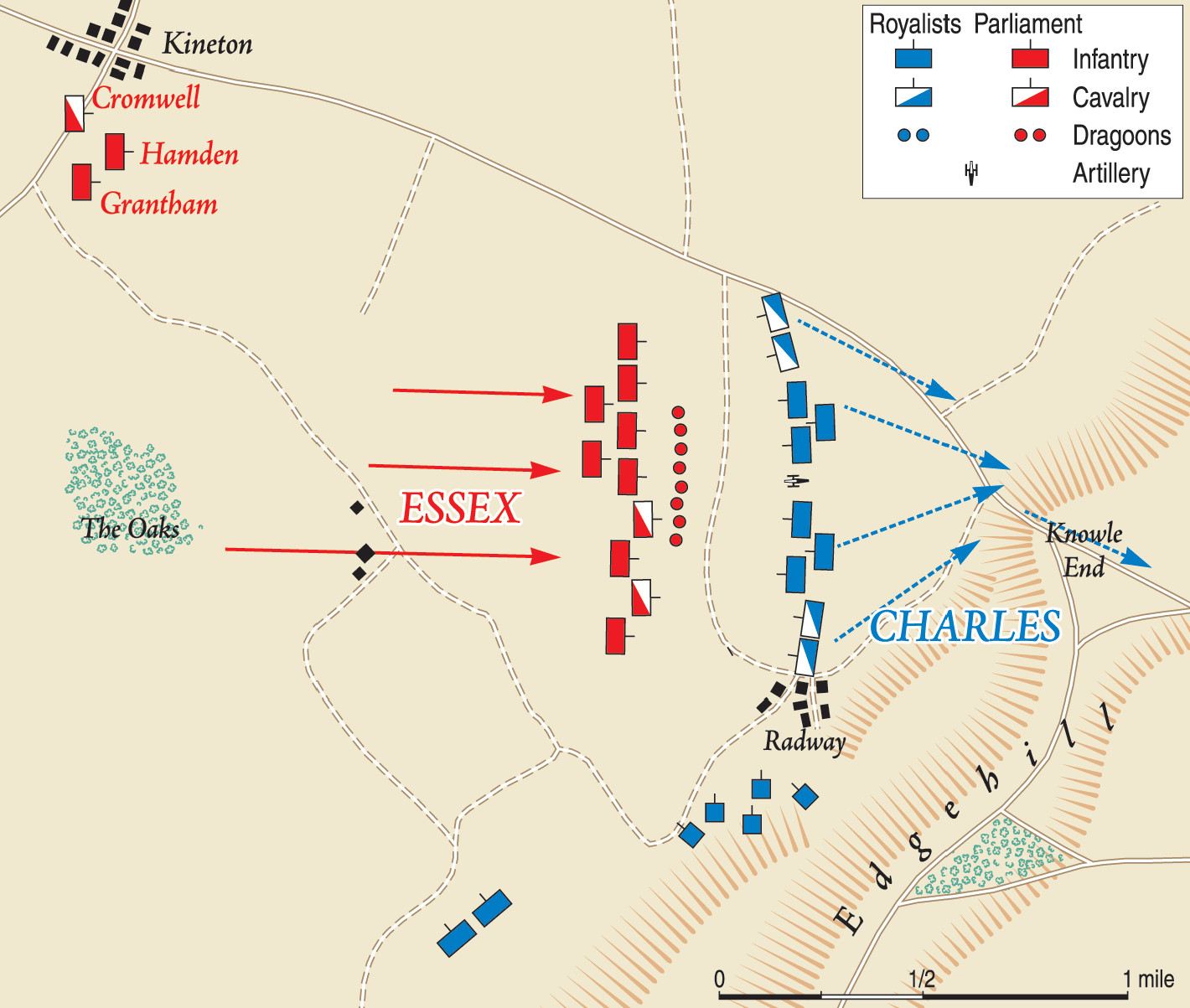

Over on the Cavalier left, Ashton’s dragoons faced myriad obstacles in the form of ditches and hedges, but still managed to force the Roundhead cavalry to retreat. The regiments of Balfour and the Lord General withdrew from the Parliamentary flank and redeployed behind the center. This left Lord Fielding’s regiment to face Wilmot’s troopers alone, and the small force of about 300 horsemen was no match for one more than three times its size. Wilmot’s troopers encountered little resistance when they crashed into the enemy’s position. Fielding’s men gave ground and ultimately fled north toward Kineton.

The skill of the Royalist cavalry was offset to a significant degree by its lack of discipline. Neither Byron’s regiment on the Royalist right wing nor Digby’s regiment on the left remained on the field to support the infantry advance. While Rupert said he gave orders for the second line of cavalry to remain on the battlefield, no record of such orders exists. Unfortunately for the Cavaliers, neither Byron nor Digby had the tactical experience to realize that their regiments could have performed better service on the battlefield than deep in the Parliamentary rear. On the Royalist left wing, Lt. Col. Sir Charles Lucas’s regiment succeeded in halting and rallying about 200 troopers from the regiments that participated in the attack.

Ramsey and his troops rode for Kineton, where they hoped to make a stand. A professional soldier from Scotland, Ramsey was a mercenary who was unwilling to fight to the death and quite willing to save his own hide when things went wrong. The Cavaliers chasing the fleeing Roundheads found plenty of opportunity for plunder in Kineton. They stopped fighting long enough to sack the Parliamentary officers’ coaches and carriages, as well as the carts and wagons of individual units. Many promptly quit the battle with their pockets stuffed full of whatever goods they could carry away on horseback. Some of the greatest spoils were gained by those who ransacked Essex’s personal coach.

A troop of horse in Balfour’s regiment commanded by Captain John Fiennes was not present when the battle began. Left behind to guard the lower crossing of the Avon at Evesham, Fiennes arrived too late to form on the battlefield, but did arrive in time to stabilize the chaotic situation in the Parliamentary rear at Kineton. He quickly rallied a retreating troop of horse to augment his own, and was further strengthened by the subsequent arrival in mid-afternoon of two additional horse troops commanded by Captains Oliver Cromwell and Edward Kightley. Having successfully prevented the Cavalier horse from going any further west than Kineton, Fiennes led his ad hoc force to join Essex in the late afternoon.

A Fight of Pikes and Muskets

From their position, the Roundhead infantry could see the king’s royal banner with its vibrant blue, red, and yellow colors floating above the men marching in Byron’s brigade just left of the Royalist center. They watched calmly as the sea of enemy soldiers advanced slowly from the base of Edgehill into the middle of the plain. Placing a great emphasis on tight order, the Royalist officers deliberately slowed the pace when it got too fast. About 100 yards from the enemy, just out of musket range, the three brigades in the front line halted and the two rear brigades advanced to form one long battle line. As the Royalists resumed their advance, the Roundheads unleashed a wall of fire at the Cavaliers.

Before the Royalists made contact, Essex’s brigade abruptly quit the field and headed for the rear. Rupert’s cavalry attack had driven back the soldiers of Ballard’s and Holles’s regiments upon the other two regiments in the brigade. No degree of berating from their officers could check their withdrawal, and Essex’s brigade plodded off away from the fight. Unable to rally his command, Essex joined Meldrum’s forces. Swearing loudly at his men, Ballard drove them from their position on the reverse slope of the ridge and into line next to Meldrum’s brigade. The advance under fire was no simple matter—Ballard’s men had to first wheel right toward the gap created by the departure of Essex’s brigade, and then wheel again left into line.

When the Royalist infantry resumed its advance, it moved slowly forward, with musketeers from both sides exchanging increasingly effective salvos. While the pikemen had some protection against the one-ounce musket balls, the musketeers for the most part had no protection whatsoever. Once the Cavaliers had closed to within 20 yards of the Roundheads, they rushed forward, with the front ranks of the pikes holding their weapons aloft and the musketeers swinging their weapons as clubs.

While the pikes on each side struggled for supremacy, the muskets flashed, causing substantial casualties. Each musketeer fired and moved to the rear to hastily reload in an effort to maintain a rate of fire that might force the enemy to retire. The gunshots shattered bones and tore gaping holes in heads and abdomens.

Fielding’s brigade, in the center of the Cavalier line, was facing a gap in the Parliamentary line that it could not fully exploit because of the presence of the Roundhead cavalry reserve. Rather than stand by idly, Fielding’s musketeers added their firepower to that of the brigades nearest to them. For a time it seemed as if the king’s foot was gaining an advantage over the Roundheads. The Parliamentary right under Meldrum was forced to give ground and retreat a short distance up the rise behind them. But the deeper ranks of the Parliamentarians and the proximity of their musketeers enabled the Roundheads to sustain their rate of fire for a longer period of time, and Meldrum soon regained the ground he had lost. When the Royalist pikes found they could not break either Parliamentary brigade, they broke off the fight and withdrew. It was at that opportune moment that the Roundhead cavalry advanced.

The Royalist Withdrawal

Balfour had shifted his regiment and that of the Lord General’s under Stapleton to the rear of the ridge to serve as a mobile reserve. Stapleton, positioned on Balfour’s right, had about 100 cuirassiers and 50 arquebusiers, while Balfour had 200 cuirassiers. Stapleton’s target was Byron’s brigade, and Balfour’s was Fielding’s brigade. Stapleton’s heavily armored cuirassiers crested the ridge first and rolled down onto the plain, sending Byron’s startled musketeers rushing for the safety of their pike blocks.

Byron’s brigade contained the Life Guard and the Lord General’s elite regiments and was the best-drilled and -armed brigade in the king’s army. By wheeling slightly left to attack Meldrum’s brigade, Byron had left his right flank exposed. Despite the shock effect, Stapleton’s first charge failed to roll up Byron’s flank. Fielding’s brigade was not so fortunate. His brigade had become overstretched trying to connect to Byron on his left and to Belasyse on his right. Balfour, seeing gaps in Fielding’s line, ordered his men to exploit them. Balfour singled out one of Fielding’s regiments and cut it off from the others.

All along that section of the Cavaliers’ line, pikemen formed squares or circles into which the musketeers rushed for protection from Roundhead cuirassiers. Balfour’s bold attack sent Fielding’s brigade, the largest of the king’s five foot brigades, reeling back. The men of Fielding’s brigade who were not captured or cut down by enemy swords threw down their weapons and streamed toward Edgehill. Following the destruction of Fielding’s brigade, Byron’s and Belasyse’s brigades also gave ground, precipitating a general withdrawal by the Royalists toward Edgehill. Boosted by the success of their horsemen, Meldrum’s musketeers harassed the retreating enemy all the way.

Balfour was not content simply with disrupting Byron’s brigade. After bringing about a general retreat by the Royalist foot, he rode for the king’s battery of heavy guns on the Royalist right flank. An unequal race ensued in which the Royalist infantry tried to reach the guns before the Parliamentary cavalry. The latter easily won the race and scattered Sgt. Maj. William Legge’s company of firelocks, whose responsibility it was to guard the guns. Having either killed or driven off the firelocks, Balfour dismounted and shouted for nails to drive through the touchholes to disable the guns. Finding that his men had not brought any nails with them, Balfour ordered his men to cut the tow ropes so that the enemy could not withdraw the guns.

11 Lost Banners of the King’s Life Guard

Seeing that the right flank of Byron’s brigade was now completely exposed following the rout of Fielding’s brigade, Stapleton launched a second assault on the beleaguered infantry. With the Royalist foot brigades in various stages of withdrawal, Essex took the opportunity to order two regiments from Ballard’s brigade—his own regiment and that of Lord Brooke—to assist in the fresh attack on Byron. Pinned in front by fresh attacks from the Parliamentary foot and assailed in flank by cavalry, Byron’s brigade became a disorganized mass of soldiers, each man thinking only of his own survival.

During the fierce melee, Verney swung the royal banner high above the fray in a vain attempt to rally the shaken Royalists. As the enemy crowded around him, he used the banner’s staff like a pike to fend off enemy foot soldiers who grabbed at it. After he seriously wounded two of them, a Parliamentary cuirassier leaned over in his saddle and hacked off Verney’s hand with one powerful stroke.

As Verney fell lifeless to the ground, Roundhead foot soldiers snatched up the banner and carried it to Essex, who was present in the thick of the action with his own foot regiment. Essex instructed his assistant, Roberts Chambers, to convey it to the rear. What happened to the royal banner from that point is the subject of continuing controversy. The official Parliamentary account holds that the banner was subsequently lost, but several Royalist sources claim that Sir Charles Lucas single-handedly took it away from a party of six troopers carrying it to the rear. The latter account, while it makes for good reading, strains credulity.

Byron’s brigade, like Fielding’s, was finished for the day. The destruction was so severe that the King’s Life Guard lost 11 of its 13 colors in the action. With Byron and Fielding routed, Wentworth, the last cohesive unit on the Royalist left, was forced to retire to the safety of Edgehill. From his position atop the hillside, Charles watched his infantry stream back toward where he stood with his entourage. Seeing Roundhead cavalry ranging freely through his army’s rear, he ordered Sir William Howard, commander of the King’s Pensioners, to locate his two sons and remove them to safety. Charles then rode forward to meet the retreating troops and try to rally them.

Final Stand of the Royalists

Rupert eventually managed to rally between three and five troops of cavalry on the Royalist right flank, which he used to temporarily delay Parliamentary reinforcements converging on the battlefield. Meanwhile, Lucas’s ad hoc force on the Royalist left flank continued to disrupt the Parliamentarian rear. Lucas’s first charge occurred early in the battle when Essex’s brigade was withdrawing from the battlefield. His troopers charged them and captured nearly all of their regimental and company colors. Lucas then launched an attack on the rear of Stapleton’s cavalry, assailing Byron’s brigade and relieving pressure on the beleaguered

Royalist infantry.

Belasyse’s brigade counterattacked on the Parliamentary left to buy time for the army to establish a new line along the stream that flowed diagonally from Edgehill toward the Parliamentary left flank. Belasyse, who led the charge himself wielding a pike, was wounded in the head as a result, but his counterattack saved the army from complete destruction. Meanwhile, the king conferred with his advisers. Despite suggestions that he abandon the infantry to its own fate and flee west with Rupert’s cavalry, Charles decided to remain on the field and observe the final outcome of the battle.

Belasyse’s and Gerard’s brigades, which retained their morale, succeeded in holding the new position as darkness approached. By using the terrain to their advantage and employing a number of smaller field guns, the Royalists made a final stand. The arrival of additional Roundhead forces in Kineton throughout the afternoon put a stop to the Royalist plunder of the Parliamentary wagon train. In the late afternoon, Fiennes arrived at the battlefield with the first group of reinforcements. He was followed by two fresh foot regiments and about 10 more horse troops.

4,000 Casualties

The opponents remained on the battlefield the next day to see whether either side would renew the fight. The Royalists redeployed the bulk of their forces in a strong position atop Edgehill. Despite having received substantial reinforcements, Essex was reluctant to renew the battle against an enemy in such a strong position. As for the king, he had no fresh forces with which to reinforce his army.

Two days after the battle, Essex withdrew his army northeast toward Warwick. Upon learning that the Parliamentarians were marching away, Rupert attacked their rear guard and managed to capture some arms and ammunition as the Roundheads withdrew from Kineton. Meanwhile, the king’s army returned to its old quarters at Edgecote, 10 miles east of Radway. The Parliamentarians had driven the Cavaliers from the battlefield, but the Royalists still controlled the road to London. As for casualties, the number buried by local villagers or treated in hospitals revealed about 4,000 total casualties for both sides. Of these, the Royalists probably suffered 2,500 and the Parliamentarians about 1,500.

Rupert’s failure to control his horsemen had lost the battle for the king. Without Rupert’s help, Lucas’s small force could not blunt the Parliamentary counterattack. The first battle of the war was a both a harbinger and a paradigm of things to come. When facing the enemy’s combined arms, the less-well-trained Royalist infantry was driven from the field. The discipline shown by the Roundheads in shunning individual heroics for the good of the common cause was sorely lacking among the Cavaliers, who fought as individuals rather than as a tightly disciplined army. At Edgehill, the Roundheads had shown a cohesion that would serve them well in the battles to come.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments