By Paul Farace

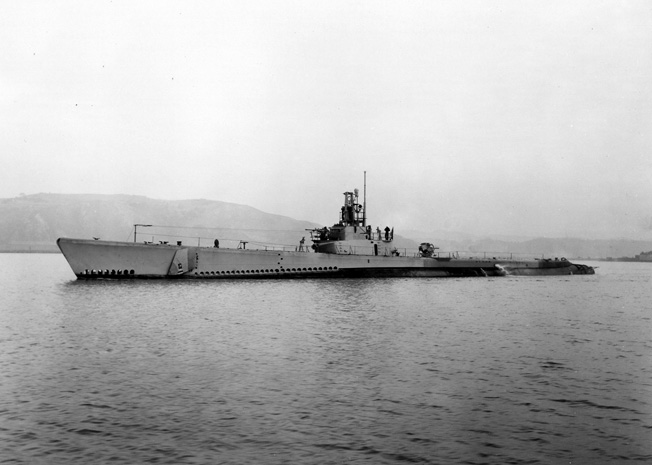

As the submarine USS Cod left Apra harbor, Guam, on the afternoon of June 26, 1945, for her seventh war patrol, her crew of 97 officers and enlisted men were all but certain that their new assignment was to be junk hunting—a thankless and dangerous job that in the words of one Cod crewman saw “Uncle Sam risk a seven million dollar submarine and crew to sink a leaky sailboat not worth more than $20,000!” But what lay ahead for Cod was a rendezvous with history—and a rescue that would unite submariners of two nations in lifelong bonds of friendship that are remembered 63 years later.

On that early summer day in 1945, thoughts of making history took a back seat to simple survival. A torpedo fire on Cod’s previous patrol had nearly caused the loss of the boat and all hands. Three crewmen fought blinding smoke to load and fire the burning electric fish even as the intense heat caused the Torpex explosive in its warhead to melt and begin dripping onto the deck—a prelude to detonation. Despite the timely ejection of the torpedo, Cod suffered the loss of one of her crewmen who drowned after being washed overboard attempting to fight the fire. After a patrol like that, the men aboard Cod hoped patrol number seven would be a gravy run.

Junk hunting was not a gravy run. After four years of unrestricted submarine warfare, Japan’s merchant fleet was decimated. In an act of desperation the Japanese forced native junks plying the coastal waters of the South China Sea to carry tiny cargoes consisting of a few dozen barrels of oil, blankets, rice, or horseshoes to their bypassed garrisons. U.S. subs were compelled to venture into shallow coastal waters to inspect and sink these contraband- carrying junks even as enemy pilots learned to home in on the thick columns of black smoke rising from the burning junks to find a U.S. sub racing for deep water—and survival.

Scuttlebutt on the Cod

Frequent fire control drills and practice dives kept Cod’s crew busy as her diesels drove her toward Batan Island. But no crew is ever too busy for scuttlebutt, and it quickly became known among the crew that few of Cod’s sizable cadre of plankowners were happy to risk their necks for the paltry payoff offered by junk raiding. These old hands, who had the most friends on the mounting number of boats declared “overdue and presumed lost,” were also uneasy about Cod’s new skipper, Edwin M. Westbrook, a veteran of seven patrols in obsolete S-boats. Several of the graybeards felt the young lieutenant commander might be too eager to make his mark in the war—at their expense.

A radio dispatch from the commander of Task Force 71 (CTF-71) decoded on the evening of July 1 assigned Cod a junk patrol station off Cam Ranh Bay, French Indochina. The crew’s fears were realized. This was prime junk territory, and the few Japanese marus transiting the area were well protected by seasoned escorts and nearly continuous air cover.

The scuttlebutt aboard Cod abruptly changed as news spread about the poor health of one of the new men aboard, Jack Hemphill, fireman second class, who had transferred aboard from one of the relief crews in Guam. Hemphill had not felt well since he was part of the painting gang preparing Cod for patrol. Now, after six days at sea, he began suffering acute nausea. Robert M. Purtill, a chief pharmacist mate aboard Cod, evaluated Hemphill and reported his diagnosis to Westbrook: acute lead poisoning..

Hemphill was relieved of duties and was confined to his bunk. Over the next several days his condition worsened as his body began swelling like a balloon. Purtill began feeding his patient intravenously and started administering sulfa drugs, but his patient continued to deteriorate.

The outlook for a successful patrol seemed gloomy as well. Army B-24 Liberator bombers scouting ahead of Cod’s course told Westbrook that no enemy shipping was to be found. On the evening of July 5, Cod arrived in the vicinity of Cape Padoran and established communication with the submarine USS Besugo. After learning that Besugo had spent three fruitless weeks patrolling the area, Cod relieved her sister sub, and in the words of Westbrook’s patrol report entry, “bid her farewell and took-up our lonely vigil.”

July 6 passed with only the sightings of a friendly B-24 and numerous local fishing boats. Hemphill, lying in his bunk in the submarine’s cramped after-battery berthing compartment, began complaining of even more severe swelling and pain in his right lumbar region. Purtill, running out of treatment options for his patient, began administering doses of an unfamiliar drug, penicillin, from Cod’s medical locker. Westbrook decided Hemphill’s grave situation warranted a radio dispatch to CTF-71. The message was encoded and transmitted just after midnight on July 7.

Cod spent the daylight portion of July 7 submerged, patrolling three miles off the boundary of the plotted enemy minefields protecting Cam Ranh Bay. Westbrook surfaced Cod just after sunset. Within 20 minutes the sub was charging eastward after receiving a dispatch from CTF-71 ordering Cod to proceed to Subic Bay, Philippines, so Navy doctors there could treat Hemphill. Throughout the night of July 7, the 312-foot submarine drove through the South China Sea to get Hemphill to a doctor.

Setting off to Rescue O-19

At 6:46 am on July 8, Cod’s radio shack received a startling message from CTF-71 informing Cod that the Dutch submarine O-19 had run aground on Ladd Reef, more than 200 miles from her present position. Cod was directed to change course for the reef and lend all assistance possible to the stranded Allied sub. Purtill was quickly called to the wardroom where Westbrook asked for good news regarding the sick crewman. Purtill’s last check on Hemphill had found him in terrible pain, but the regular doses of penicillin had begun to show slight success in reducing the crewman’s discomfort. Grasping at the slim bit of good news, Westbrook felt that risking the life of one of his crewmen for an entire crew of Dutch submariners might be a worthwhile gamble. Within minutes, the gyrocompass repeaters aboard Cod swung to a new heading as the sub drove toward Ladd Reef at four-engine speed.

The scuttlebutt aboard Cod now focused intently on the latest news of their sick shipmate. As Cod made her daylight dash across the South China Sea, two air contacts on the boat’s air search radar clearly indicated that the skies overhead could not be relied upon as friendly, even at this late stage of the war. The first contact spotted did not respond to Cod’s IFF (identification friend of foe) inquiry, but a second contact 20 minutes later flashed a positive IFF signal. No further contacts, either aircraft or surface, were made that afternoon as the distance closed between the two Allied subs.

Without a clear picture of the situation aboard the grounded Dutch sub, Westbrook prepared to bring the Dutch crew immediately aboard. He assembled a rescue team armed with heaving lines, two of Cod’s inflatable boats, and all of her life rings. Below deck Cod’s cooks prepared large quantities of hot soup and coffee while empty bunks and dry clothes were readied.

At 8:35 in the fading light of July 8, the dark shape of a submarine loomed in the distance, surrounded by whitecaps breaking over the coral fingers of Ladd Reef. A signal light flashed from the O-19 giving her exact location on the reef. Hopes of a quick crew transfer for the sake of Hemphill faded as a second message soon blinked across the darkening waters asking that Cod attempt a tow at dawn. Before backing Cod away from the treacherous reef currents, Westbrook signaled his Dutch counterpart that they would see each other again at dawn. The skipper of O-19, J.F. Drijfhout van Hooff, indicated that he had not lost his sense of humor in his dire situation by signaling back, “We will certainly be here.”

In Cod’s after-battery, Hemphill lay still in his rack, attended by volunteer nurses recruited from among off-duty shipmates.

The Reef’s Death Grip on OS-19

As the sky in the east brightened with the coming dawn on July 9, Cod raised her keel-mounted sound gear and pit sword, flooded down at the bow, and cautiously commenced a bow-on approach to the stricken sub. Powerful reef currents that continuously pulled Cod to the east made a stern tow impossible. With less than 500 yards between the boats, Cod’s deck watch was blinded by a terrific rain squall that reduced visibility to less than 200 yards for more than an hour. At 7:21 the rain abated, revealing to Westbrook the sight of a submarine hopelessly aground. Empathizing with his Dutch counterpart, Westbrook was determined to give the towing attempt his best effort.

At 8:06, Cod’s deck crew received the first line from O-19 attached to a length of new 11/2-inch stainless steel cable that was secured through Cod’s bullnose. At 8:35 on the rising tide, both boats began backing as gunners aboard O-19 commenced rapidly firing their 88mm deck gun in a desperate attempt to jar their boat from the grip of the reef. At 8:40, the stainless steel line parted with a loud crack.

As crewmen aboard the subs attempted to recover the parted ends of the cable, Cod’s SD radar announced the approach of an aircraft that offered no IFF signal. Lookouts aboard both subs nervously scanned the skies for five long minutes until the contact could be identified as an Army B-24. Using Cod’s short-range VHF voice radio, Westbrook learned that the aircraft was part of an air umbrella ordered by CTF-71 to safeguard the rescue effort. A Navy PB4Y-2 Privateer electronic surveillance aircraft soon joined the B-24.

At 11:55, with the repaired cable in place, both boats began backing again for a second attempt. Within a minute, the cable broke a second time. Crewmen aboard both boats scrambled to retrieve their ends of the cable as Westbrook ordered his executive officer, Lieutenant Ken Beckman, to take one of Cod’s rubber boats and confer with the Dutch skipper.

Arriving aboard the O-19, Beckman learned the crew of O-19 had become very resourceful in their efforts to free their boat. All ballast had been pumped overboard or moved to the stern, the bow torpedoes and all spare equipment now littered the reef around the O-19. During the first two tow attempts, massive Kingston valves were closed to seal the ballast tanks of the O-19 as her low-pressure blowers pressurized them as much as possible. When quickly opened, the Kingston valves explosively released the entrapped air, rocking the 262-foot-long sub a few inches. But Beckman also realized that an unusual offensive feature of the Dutch boat—20 vertical minelaying chutes in her ballast tanks—now doomed her. Coral outcroppings on the reef had penetrated the bottoms of many of the chutes, holding the O-19 in a death grip.

Challenges on the Reef

O-19’s officers had one last plan to free their boat, and at 2:16 pm, Drijfhout van Hooff arrived aboard Cod to pitch his idea to Westbrook. The O-19’s anchor chain could be wrapped around her conning tower and fixed to Cod for a final tug attempt during the next morning’s high tide. Westbrook was certain that even if the plan worked the chain would likely inflict severe structural damage to the Dutch sub. With the insurance of constant air coverage, Westbrook agreed to try.

Cod’s bow maneuvered to within 10 feet of the O-19’s stern to allow the Dutch sub’s heavy anchor chain to be taken aboard and prepared for use as a towing line. The powerful currents allowed Westbrook to maintain his position for no more than 20 minutes before he was forced to back off and come in for another approach. Crewmen on Cod’s bow took constant soundings. The jagged bottom was never more than three fathoms away.

At 4:05 pm, the Dutch skipper returned to his stranded sub, and a cable attached to the anchor chain was passed back aboard O-19. The crew of the O-19 quickly realized their sub’s capstan was unable to lift the 80-fathom length of chain and requested Cod lift it for them. Unwilling to risk the safety of Cod in the shifting currents of the reef with daylight quickly fading, Westbrook signaled to Drijfhout van Hooff that he would return to lift the chain in the morning. He then moved Cod several miles off the reef for the night.

The night’s scuttlebutt included high marks from the old hands for Westbrook’s expert boat handling abilities while fighting the reef currents. The other good news came from Purtill. Patient Hemphill was greatly improved and was able to sit for a short time at one of the tables in the crew’s mess. But Purtill had a new medical crisis to deal with—many of the men handling lines topside throughout the day became severely sunburned. Unaccustomed to dealing with equatorial sunshine on submarine war patrols, many of Cod’s topside crew shed their foul-weather gear after the morning’s rainsquall passed. By the time the light overcast gave way to full sunshine, few realized their beet-red skin had already absorbed too much sun. Lieutenant Charles Podorean, Cod’s gunnery and torpedo officer, spent most of the day topside wearing only boxer shorts and sandals. Now, as he climbed into his stateroom bunk to sleep, his body shook violently with chills as he tried to fight off the accompanying nausea.

Westbrook finished his breakfast in the wardroom and was on Cod’s bridge by 5:47 on the morning of July 10. By 7:15, the first manila line from O-19 landed on Cod’s forward deck as her crew prepared to lift the Dutchman’s anchor chain. But Westbrook realized that conditions on the reef had deteriorated overnight—even more powerful currents were pulling Cod out of position faster than they did on the previous day. Several hours passed as the murderous currents repeatedly snagged the chain towline on jagged coral outcroppings. Life jackets were inflated and tied to the end of the towline as a marker in an attempt to speed the retrieval process each time Cod was forced to drop the line and pull back to make a new approach.

At 9:50 am, the day’s air cover, a PBY Catalina flying boat, made its presence known to the Allied subs below with a low pass over the reef.

Condemning O-19

Several Cod crewmen were put over the side in a rubber boat in an attempt to free the towing rig, which consisted of the bitter end of the O-19’s chain, a segment of manila mooring line, and 20 fathoms of 21-thread rope. Westbrook, his nerves frayed by the constant maneuvering, was now chain-smoking as he backed clear once more and began yet another approach to the O-19—his final attempt, he declared to the bridge watch.

The fouled rigging was finally freed from the grip of the reef and secured around Cod’s bow capstan, which began taking up tension. Crewmen aboard the two subs stared intently as the towing rig was pulled from the water between the two boats. Then at 11:45, just as Cod put high tension on the line, it parted for the last time, sealing the fate of the O-19.

Cod crewmen stared in silence across the dozen yards of open water at their Dutch counterparts. Most of the Dutch crew was now topside, motionless, staring at what remained visible of the severed towline.

Westbrook ordered a message flashed to his Dutch counterpart: “We will standby to take off personnel.”

Westbrook wrote in his patrol report for the day: “Felt almost as bad as the O-19 skipper at his having to abandon his ship. However, did not see what more we could do. Had worked eight hours yesterday and six today with no progress. Had touched bottom forward ourselves at least once in our many approaches, and did not desire to have two submarines aground. Our towing gear was makeshift, and our personnel, though willing and resourceful, were inexperienced at rigging for a tow. Also, Jap planes or subs might have appeared at any embarrassing moment.”

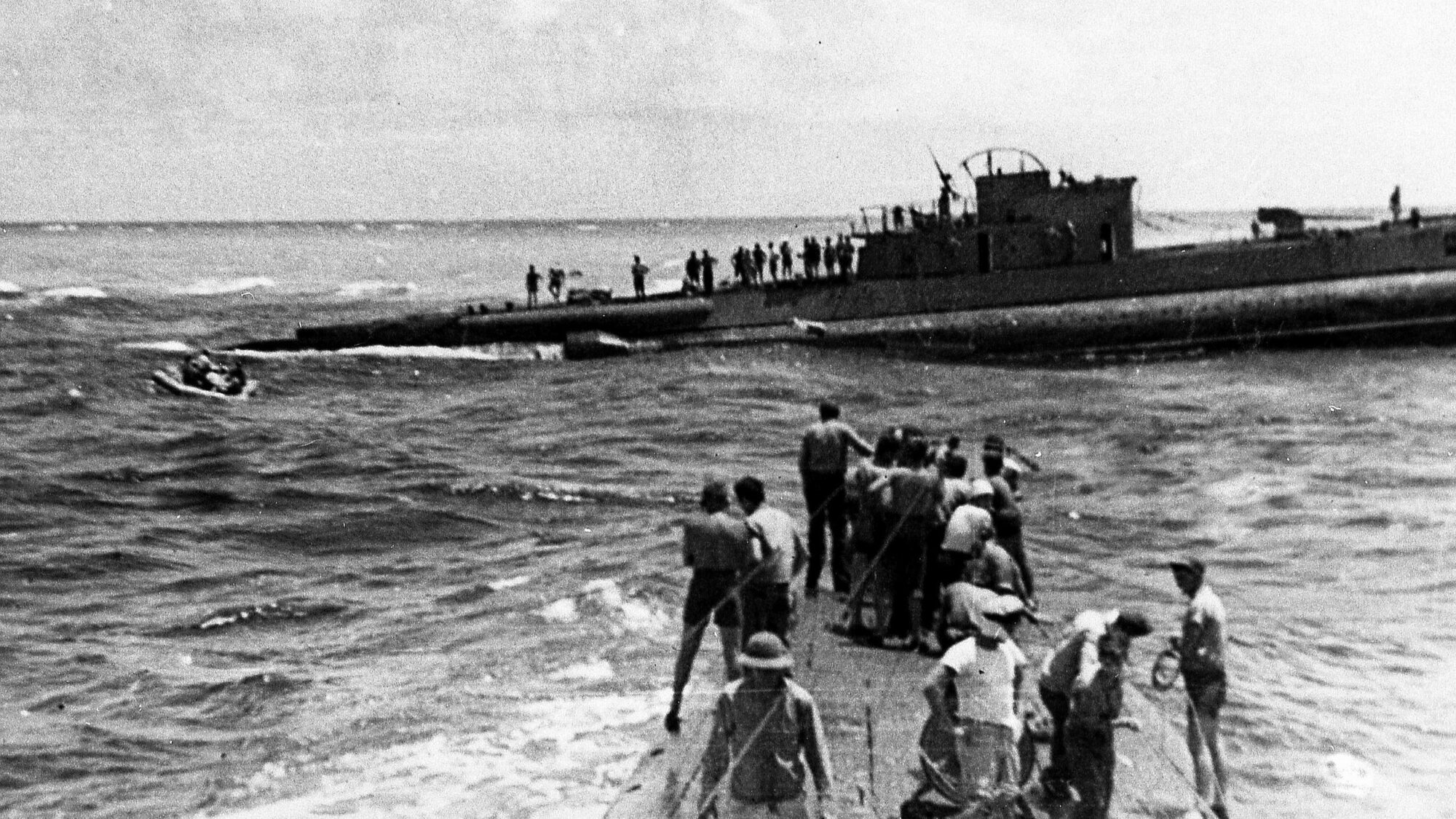

Deck hands lashed together Cod’s two yellow inflatable rafts and put them over the side. Lieutenant Thomas Hurst III and crewmen Dan Krusenklaus, Jr., and George McKnight soon boarded them. The trio had to paddle furiously against the powerful currents to reach O-19 to oversee the crew transfer. At 12:55, the first load of Dutch crewmen was hauled aboard and sent below.

The faces of the O-19 crewmen clambering aboard, an assortment of ethnic Dutch and Javanese, all bore expressions of total exhaustion, heartbreak, and relief that they were no longer sitting ducks for the nearest enemy ship or plane. Most arrived aboard Cod with only the clothes on their backs, a few carried tiny rucksacks. One of the Dutch petty officers cradled a small, carved doll under his jacket—the O-19’s good luck charm.

A First Attempt at Destroying O-19

Westbrook ordered Lieutenant Podorean, still suffering from sunburn, to take two of Cod’s scuttling charges and lead a demolition team to O-19 once the next load of Dutch submariners left the rafts. Arriving aboard the Dutch boat, Podorean and his team set about their grim task, noting that the Dutch crewmen preparing to leave their home for the last time could not bear to look at the explosive charges or acknowledge the team’s mission. Below decks, the Americans were surprised to find the Dutch sub was fully stocked with beer and spirits, and they helped themselves to samples. Once the charges were wired and the timers set, their empty canvas equipment bags were filled with souvenirs from the Allied sub—not all of O-19, or its libations, would be lost to the reef.

At 2:55, under a brilliant sun, the last boatload arrived aboard Cod; among them was Drijfhout van Hooff. Cradled under his arm was the O-19’s flag.

Podorean reported to Westbrook that the demolition charges were set with a 90-minute delay, sufficient time for Cod to back away from the reef and conduct a trim dive to compensate for the added weight of the 56 Dutch submariners now aboard.

At 3:45, Cod surfaced and approached to a point about 1,000 yards off the starboard beam of O-19 to await the detonation of the charges. At 4:27, a column of black smoke spewed out of the conning tower of O-19. A moment later the thunderclap sound of the detonation rushed past Cod’s position.

Westbrook now prepared to fire his first shot of the war as a submarine commander. Realizing that most of the men had never seen a torpedo explosion, he invited off-duty crewmen to come topside. At 4:36, the second charge detonated, sending more smoke skyward along with one of O-19’s deck hatches.

A minute later a Mark 14 torpedo, set for a depth of zero feet to allow it to pass over the reef, was fired at a point just abaft the O-19’s conning tower. Once the firing button was pushed, the tracking party scrambled up the hatch to the bridge, intent on seeing the effects of their handiwork. Thirty-four seconds later a flash engulfed O-19’s conning tower as a massive black and brown cloud of debris surged skyward.

Cheers and exclamations among Cod’s crew were quickly stanched as they realized the Dutch crewmen among them were weeping. Many of the Cod’s crew soon wiped their own moist eyes as the contingent of Dutchmen began singing “Het Wilhelmus,” their national anthem.

Sinking into the Reef

As the smoke cleared, Westbrook noted a massive hole in the side of O-19, but the tough Dutch sub had not budged an inch. At 4:43 a second Mark 14 was fired, this time at the after torpedo room of O-19 in the hope it would also detonate the two torpedoes stowed there. The fish broached about 100 yards short of its target before plunging back under. A moment later it glanced off a coral head and leaped out of the water to slam against the Dutch sub. Instantly, a second flash, followed by an even larger explosion, disintegrated the stern of O-19 and left the boat a smoking wreck.

Virtually every off-duty crewman was topside to witness the spectacle. As the thunderclap of the detonation reached Cod, the men realized that pieces of O-19, large and small, were now flying toward them. The submariners scrambled for the limited protection afforded by the tiny free-flooding storage area in the aft end of Cod’s conning tower superstructure as debris from O-19 splashed into the water surrounding them.

Not wanting to loiter at the reef any longer than necessary, Westbrook called his gun crew to action. Over the next 10 minutes, Cod’s 5-inch, 25-caliber deck gun pumped 16 rounds into the shattered hull.

With the boat now burning and holed along its hull, Westbrook backed Cod away from Ladd Reef a final time and headed toward Subic Bay. Glancing backward, Westbrook noted that O-19 had taken on a slightly greater list but was still held fast by the reef. Westbrook wrote in his patrol report that he “wished my first torpedo fired had been at a slant-eye instead of this. Could appreciate the captain’s feelings as he silently watched his boat being destroyed.”

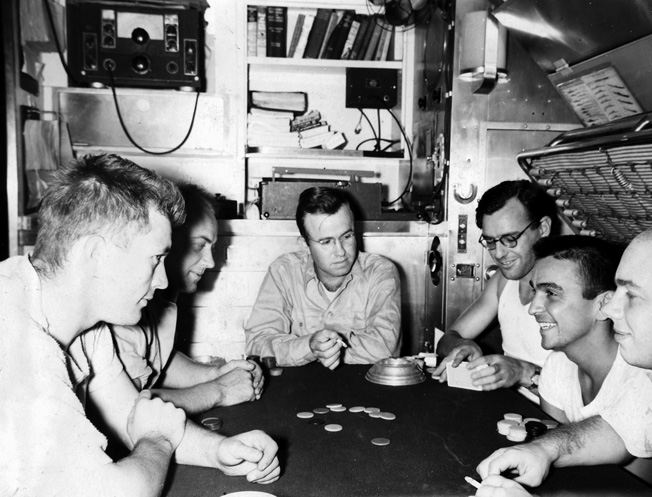

Camaraderie Among the Crews

Belowdecks two complete submarine crews occupied a space hardly large enough for one. Cod’s chief cook, George Sacco, busily prepared a double order of fried chicken, mashed potatoes, biscuits, green beans, and carrots for supper. Ice cream, made in Cod’s ice cream machine, would be served for dessert. The Dutchmen, resigned to a seemingly inexhaustible supply of canned beef stew aboard O-19, were amazed at the galley fare aboard Cod.

Over dinner in Cod’s wardroom, the Dutch officers described how O-19 rushed from its home base in Fremantle, Australia, to deliver special mine warfare training equipment to the new Allied submarine base at Subic Bay. Their superiors told them that their offensive patrol could commence only after they delivered their cargo. Heavy overcast for most of the previous week had prevented van Hooff and his navigator from obtaining star fixes for celestial navigation. Relying on dead reckoning alone, van Hooff expected to pass the dangerous shoal waters by a comfortable margin.

That margin vanished in an instant with a terrible screeching sound just after 4 am on July 8. In an instant, men and loose equipment hurled against the forward bulkheads of the sub. O-19, driving at 18 knots with as much of her hull above water as possible to make her best speed, came to a complete stop in just 60 feet. O-19’s engineering officer, who had the watch, immediately ordered full astern, but the only result was heavy vibration throughout the boat as the tips of her twin screws clattered against coral. Realizing they were sitting ducks once the sun rose, the Dutch captain quickly encoded and transmitted an urgent plea for help to CTF-71.

The three-day trip to Subic Bay was calm if uncomfortable aboard the U.S. submarine. According to Cod crewman Howard Dishong there was congestion around the crew’s heads, but no accidents occurred. Like many of Cod’s crew, Dishong turned his bunk over to the guests and slept at his duty station among the diesels. The additional bodies made the air below decks very stuffy despite the continuous operation of Cod’s air conditioning plant. Westbrook responded by periodically closing Cod’s main air induction valve and allowing the diesels to draw their air through the forward torpedo room hatch. The result was a wind tunnel effect through the boat that greatly improved living conditions.

Cod moored alongside the tender USS Anthedon in Subic Bay at 8:37 on the morning of July 13. After a brief farewell among the two crews, the Dutchmen were transferred to the tender. Drijfhout van Hooff remained in Subic Bay while his crew thumbed a plane ride back to Fremantle.

Cod topped off her fuel tanks and returned to the French Indochina coast to continue her junk-hunting mission. Over the next month Cod boarded and sank more than 23 junks laden with enemy supplies. Twice she was strafed and bombed by Japanese aircraft. One Cod boarding party was trapped aboard the junk they were inspecting when a strafing Japanese aircraft forced to the Cod to crash dive. The men drifted in the Gulf of Siam for two days believing Cod had been sunk before being rescued by the submarine USS Blenny and returned to their boat.

Westbrook finally got a chance to attack a small, well-protected Japanese convoy, but all of his torpedoes missed. After dark, in very poor visibility, as Westbrook approached for a second attack on the convoy his surface radar burned out, thwarting his attempt to track the ships for the remainder of the night. In the morning two other U.S. subs also attacked the convoy. All their torpedoes missed as well.

On the morning of August 4, Cod was released from her patrol station and ordered south to Fremantle. Arriving at the sub pier on the morning of August 13, Cod was greeted by the crew of O-19, who invited their new friends to a formal thank-you party scheduled the next night at the Dutch officer’s club across the harbor.

At the party, the submariners and their dates enjoyed live music, food, and the potent local Swan lager. As the band finished a polka, someone grabbed the microphone on the bandstand and announced that radio stations were reporting that Japan was seeking surrender terms. The two submarine crews, who realized that they had survived the war, celebrated as long lost family into the next day.

Within a few weeks Cod was heading back to the United States. In the final days of her commissioning, Cod crewmen designed and commercially produced battle flags to document their wartime exploits. Featured prominently on the flags is a martini glass over the name “O-19” to commemorate the only rescue in naval history involving submarines of two nations and one hell of a thank-you party that followed. Also on the flags, located just below the Navy’s twin dolphin submarine insignia, is the Onderzeedienst submarine service ribbon of the Royal Netherlands Navy, commemorating Cod’s unique status as an adopted submarine of the Dutch Navy. That honor was bestowed by members of the Dutch high command between the many toasts at the party.

The USS Cod After the War

Westbrook and Drijfhout van Hooff became close friends after the war. While serving as a naval intelligence officer in Singapore in the early 1950s, Westbrook had a Navy plane fly over Ladd Reef and film the wreckage of O-19 as a memento to his Dutch friend, whom he often chided by saying, “There is no justice in this job, you lost your boat on a reef and make Admiral. I saved your hide and only made Captain!”

Cod was recommissioned in 1951 to help train NATO antisubmarine forces in the Atlantic. Cod’s crew finally got their gravy run—several in fact. Cod’s Cold War cruises took her to exotic harbors throughout the Caribbean, including Curaçao and the Netherlands Antilles, where van Hooff was captain of the port.

Westbrook died in 1973, not long after returning to his home in Burlingame, California, from a visit to van Hooff’s home in the Netherlands.

Decommissioned in 1954, Cod was later taken out of mothballs and towed to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1959 to serve as a naval reserve trainer. Cod was transferred to civilian custody in 1976 to begin service as a memorial to the men of the Silent Service who gave their lives in defense of their nation. In 1986, she was declared a National Historic Landmark in recognition of her status as the last unmodified World War II fleet submarine in existence.

While researching Cod’s history at the National Archives in 1992, her civilian caretakers discovered long-forgotten color movies of Cod’s last war patrol, featuring the rescue of the O-19 crew. The films were given their first showing at the next Cod crew reunion only a few weeks later. Seeing themselves on the screen as young men performing a historic rescue again brought tears to the eyes of nearly everyone present. Later reunions would include several O-19 crewmen.

Today, Cod also serves as a rallying point for members of the Northeast Ohio Dutch-American Heritage Society, who help Cod’s memorial crew mark the anniversary of the rescue each year with a reenactment of the O-19’s flag transfer followed by a picnic at the Cod’s dock. Participants in the reenactment, like many visitors, love to have their picture taken under Cod’s World War II scoreboard. There, in addition to the many Japanese kill flags, is a martini glass painted above the name O-19 that commemorates a unique rescue and an enduring friendship between two sub crews.

Brilliantly written account thank you Mr Farace.

Very interesting article. And a belated thanks to the Cod from Holland!