By Roy Morris, Jr.

No one expected this—not the fiercest “fire-eater” in South Carolina or the flintiest abolitionist in New England. By the time the guns fell silent at Shiloh on the night of April 7, 1862, soldiers on both sides of the battlefield realized that they had endured something never before seen in American history. Nearly 24,000 men had fallen dead or wounded among the peach orchards and tangled woods in southwestern Tennessee, more than the total loss from all three of America’s previous wars combined. Small wonder that New Orleans writer George Washington Cable, himself a former Confederate, would later write: “The South never smiled again at Shiloh.”

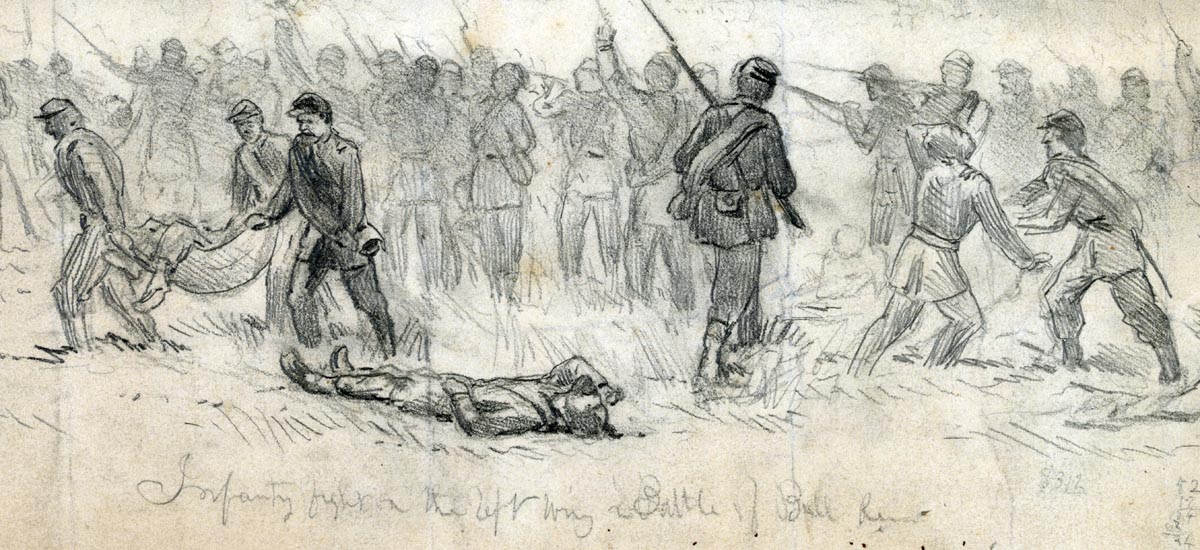

Neither, for that matter, did the North—at least not for another three long years. Shiloh was the first truly disorienting battle in the national experience, a battle in which large numbers of poorly led troops stumbled into one another, blazed away, fell back, came together again, and stopped butchering each other only after darkness, rain, and exhaustion put an end to the fighting. There would be other battles like Shiloh in 1862, many of them commemorated in this special issue of Civil War Quarterly.

Where America’s Childhood Ended

But there would never be another Shiloh, for that was where America’s childhood ended. After Shiloh, all cocky talk of bloodless victories and cowardly foes gave way to the sickening realization that a war started almost cavalierly one year earlier would not be ending easily—or any time soon. It was no coincidence that the two generals destined to lead the main armies of the opposing regions rose to prominence in 1862. For the North, it was an unprepossessing, rumpled officer from the Midwest, Ulysses S. Grant, a man who had failed at almost everything he touched since graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point two decades earlier. Grant began his improbable march to high command with his stunning victory at Fort Donelson in February 1862 and his hairbreadth survival at Shiloh six weeks later. For the South, the rising star was Robert E. Lee, also a graduate of West Point, but a man from a very different background than Grant. The patrician son of old-line Virginia royalty, Lee would lead the Army of Northern Virginia through some of its bitterest battles in 1862: Second Manassas, the Battle of Antietam, and Fredericksburg. Two of those would be overwhelming Confederate victories, but the third—Antietam—would be a crushing defeat (and the bloodiest single day in American history). Grant and Lee would begin their long march toward each other in 1862, although it would be another two years before they met for the first time on the battlefield.

A Watershed Year for Both Sides

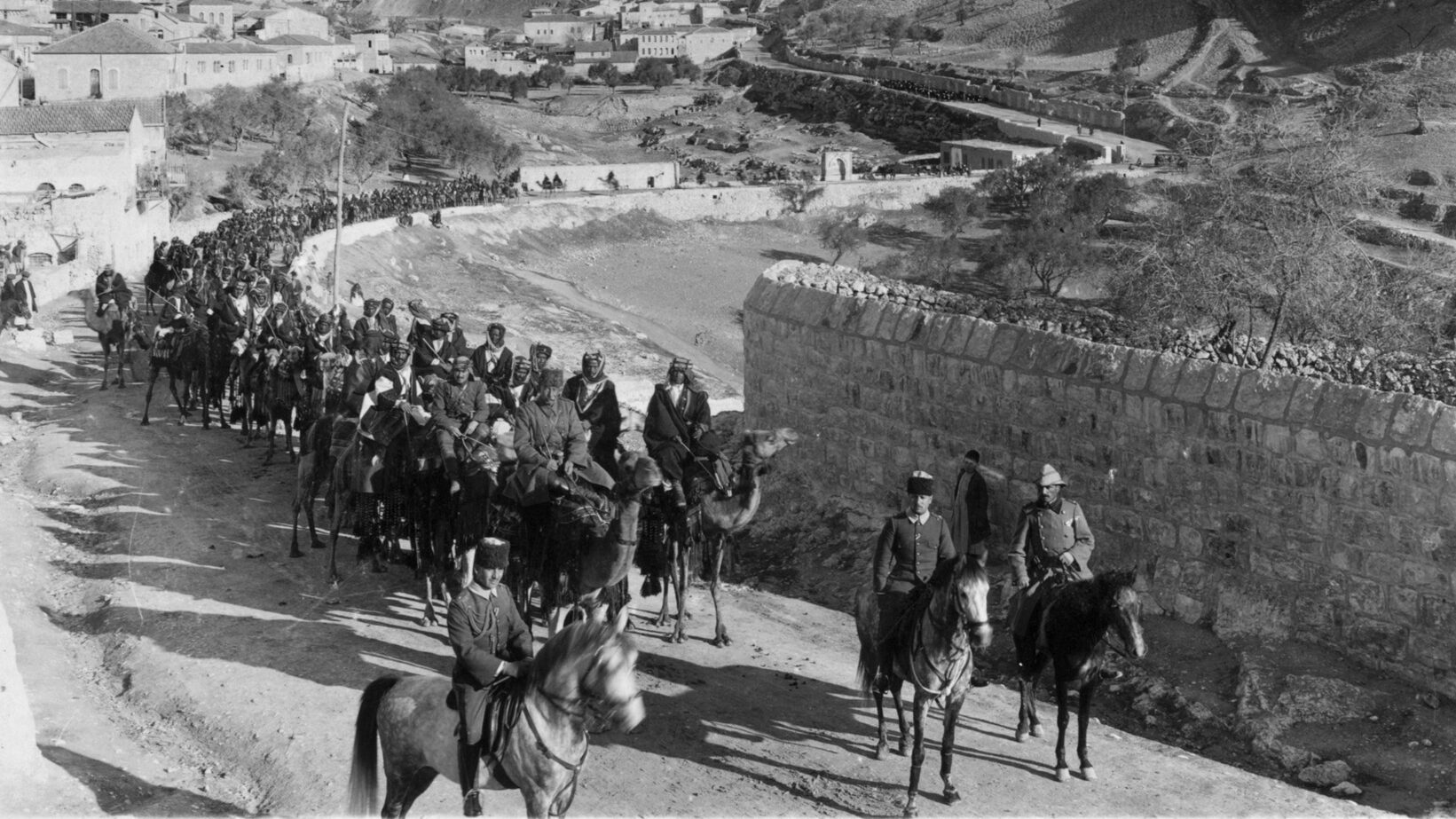

In the meantime, there were other battles to be fought in 1862, including the significant Union victory in the western theater of the war at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March. Sandwiched between them were other Union victories, these on the water, when Admiral David Farragut successfully seized the South’s largest city, New Orleans, and a Federal ironclad, Monitor, fought off the Confederate behemoth Virginia at Hampton Roads, Virginia, ushering in a new era in naval warfare. For both sides, 1862 would be a watershed year, a time in which the amateur armies raised so hastily the previous spring would learn how to fight, and kill, each other with increasing efficiency. From the men in the ranks to the officers on horseback, the war would progress with a grim inevitability. The only certainty was that there would be even worse days to come. Shiloh had seen to that. Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments