By Eric Niderost

Long columns of blue-clad French troops marched east though the sun-baked plains of northern Italy in late June 1859. Normally, Lombardy was blessed by the most fertile soil in the peninsula, nourished by the mighty Po River and its many tributaries, but this summer was unseasonably hot, scorching man and beast alike and desiccating the normally bountiful fields. The French troops pressed on, their spirits buoyed by the memory of past glories—glories they hoped to emulate, if not surpass, on this campaign. It was here that Napoleon Bonaparte had revealed his genius through a series of victories at Arcola, Rivoli, and Marengo some 60 years earlier. Many of the new Gallic soldiers had won laurels in the recent Crimean War against the Russians. There was little doubt in their minds that they could achieve an even greater triumph over a seemingly inept Austrian enemy.

Napoleon’s Nephew and his Ragged Army

Emperor Napoleon III commanded the French army. Although he completely lacked his uncle’s talent for war—who didn’t?—he nevertheless felt compelled to continue the Napoleonic legend. Louis Napoleon was a master politician but an indifferent soldier. He had attended a Swiss military academy as a young man, but had no experience as a field commander on active service. In truth, he was completely unsuited to be a leader of large armies, but tradition demanded that he follow in his famous uncle’s footsteps. Accordingly, the goateed, 51-year-old emperor ordered his sweating columns toward the Mincio River, not knowing that a somewhat reinvigorated Austrian army—at least by Viennese standards—was in the process of forming against him. Both armies were groping in the dark. Intelligence was faulty, and Louis Napoleon had no real idea where the enemy might be. The French army did have some relatively modern elements to it, and an observation balloon actually detected Austrian movements. Unfortunately, the emperor downplayed the report.

The French army was always known for its reckless courage and offensive spirit, its irresistible élan. On the march, however, the French sometimes looked more like an army of vagabonds than a professional fighting force. Columns were ragged, uneven, and at times almost slovenly. Red-trousered soldiers walked along singly or in bunches. It was torture wearing the heavy packs and blue woolen tunics in the suffocating heat, and the temperatures were made worse by clouds of choking dust kicked up by thousands of tramping feet. Although they didn’t know it, these sweat-drenched Frenchmen were marching toward one of the greatest battles of the 19th century.

The Blooming of Italian Nationalism

Their footsore progress was more than just a march to battle—it was the first fitful, halting steps to the rebirth of Italy as a unified country. In the mid-19th century, “Italy” was more an expression of geography than a true nation. The Italian boot was a patchwork of independent states, the most important of which was Piedmont-Sardinia. The duchies of Tuscany, Parma, and Modena were insignificant entities, and the southern half of the peninsula was dominated by the semimedieval and corrupt Kingdom of the Two Sicilys. Central Italy was ruled by Pope Pius IX, the head of the giant Catholic Church.

Most of the Italian population, some 27 million souls, was composed of illiterate peasants, but by the mid-1800s there had been stirrings of patriotism and nationalism. This nascent nationalism was centered in part on the desire to expel the Austrians from Italian soil. Austria ruled Lombardy and Venetia, important provinces on both a cultural and historical level. A united Italy would be unthinkable without them. Expelling the Austrians would be no easy task, but one man believed he had a workable plan. Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour, was the prime minister of Piedmont-Sardinia. A hard-headed realist, thoroughly Machiavellian in thought and deed, Cavour realized that Sardinia wasn’t strong enough to tackle Austria alone in open warfare. A decade earlier, the so-called First War of Italian Independence had ended in crushing defeat at the hands of the powerful Austrian empire.

Cavour and Napoleon Conspire

With that in mind, Cavour hoped to enlist the aid of France’s Napoleon III. Once the Austrians were expelled from the peninsula, Italy might be united under Sardinia’s King Victor Emmanuel II. Cavour arranged to secretly meet Napoleon at Plombières, France, where the French monarch customarily took the waters. The cloak-and-dagger aspect of the encounter appealed to Louis Napoleon, who delighted in subterfuge and backdoor deals. The pair met on July 19, 1858.

An inveterate conspirator, Louis Napoleon didn’t even bother to inform his foreign minister, Count Alexandre Walewski, of the clandestine negotiations. The emperor could be ruthless if his personal power was threathened, but he retained much of the dreamy-eyed romanticism of his youth. He sympathized with the poor and downtrodden, and genuinely wished Italy to be free of foreign control. As a young man of 23, full of ardor and idealism, Louis Napoleon had actually fought alongside Italian patriots in an abortive uprising. Now, almost 30 years later, he was willing to help unify Italy under Piedmont-Sardinia’s House of Savoy.

After Austria was defeated, Louis Napoleon was planning to add Lombardy, Venetia, and the duchies of Modena, Parma, and Lucca to Piedmont-Sardinia, creating a Kingdom of Northern Italy. Remaining Italian states would fall into Piedmont’s orbit with the creation of a loose confederation under the nominal aegis of the Pope. The conspirators were in general agreement, but Louis Napoleon insisted that France receive due compensation for her help. The emperor wanted to annex Savoy and Nice, although a final settlement would have to wait until Austria was defeated.

The Second War of Italian Independence Begins

The next few months saw increasing tension between Austria and Piedmont-Sardinia. Austria had gotten wind of the secret meeting at Plombières—yet another reason to stifle Piedmontese ambitions before they got out of hand. In the spring of 1859, Austria demanded that Piedmont-Sardinia demobilize its forces and withdraw its troops along the border. To Cavour, this was a heaven-sent ultimatum, one that he gleefully rejected. The Franco-Austrian War of 1859, also called the Second War of Italian Independence, was now a reality.

Austria’s plan was simple and direct: invade Piedmont, take its capital at Turin, and crush the Piedmonese army before the French could intervene. On paper, at least, it seemed an easy task. The Austrian Second Army was massed along the Ticino River, the waterway marking the boundary between Piedmont-Sardinia and Austrian-controlled Lombardy. The Austrians were a mere 75 miles from Turin. The Second Army numbered 107,000 men and 364 guns, while the Piedmontese army could only muster some 60,000 troops.

Two Very Different Armies

The Austrian army seemed a formidable force, but the coming campaign would reveal serious weaknesses. The infantry was generally dressed in traditional white tunics, although as summer progressed they donned kittels, linen tunics that were technically barracks or fatigue wear, but were useful in the torrid heat. The soldiers were armed with the Lorenz rifle-musket, an up-to-date weapon that was more accurate than a smoothbore. But a kind of dry rot had weakened the Imperial Army’s command structure. There were too many incompetents in positions of responsibility, men who owed their ranks more to court connections than to any innate ability. This was particularly true of the Second Army’s commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Count Ferencz Gyulai. He made an impressive appearance at Vienna reviews, but on campaign he was indecisive, overcautious, and slow.

By contrast, the Piedmontese army was well trained, its forces recently reorganized. Some of its light infantry units, like the feather-hatted Bersaglieri, were renowned as tough and courageous fighters. King Victor Emmanuel himself was a good soldier with sound military instincts. The Piedmontese army did have some weaknesses—many of its regiments were equipped with old-fashioned smoothbore muskets—but overall it was a formidable fighting force. The Piedmontese also had some rugged and controversial auxiliaries—the Cacciatori delle Alpi, or “Hunters of the Alps,” a brigade of 2,000 irregulars led by Giuseppe Garibaldi. The fiery Garibaldi was an out-and-out revolutionary who had an unsavory reputation in conservative and church circles. Louis Napoleon consented to the Cacciatori with some reluctance, because such elements were also strong in France.

Early Austrian Blunders

Austrian incompetence, not Piedmontese valor, saved the tiny country in the early weeks. The Austrian army crossed the Ticino, but soon its advance slowed to a crawl. Young Austrian officers spoke of taking Turin, but progress was glacially slow. At times the Second Army was marching four miles a day, its probes half-hearted and overly cautious. Heavy rains slowed progress, but a dilatory Gyulai bore most of the blame. Soon fear replaced inaction, as Gyulai worried about the French troops he knew to be pouring into Piedmont every day. The Austrian field marshal began to suspect that the French would advance south of the Po River through Piacenza and cut his lines of communication. Gyulai ordered his army to retire lest they be caught and attacked from behind.

In reality, the French and their Piedmontese allies intended to thrust north, not south. The addled Gyulai had thrown away Austria’s last chance for victory, at the same time handing the initiative to the enemy. In the meantime, the French had been far from idle. An expeditionary force of over 100,000 men was to get under way as soon as the first Austrian whitecoats crossed the Ticino. Part of the army embarked on ships for a sea journey to Genoa, but other French regiments traveled by train into northern Italy via the Mont Cenis Pass—the first time in history that the railroad was used to transport troops on a military campaign. The highly efficient French railroads managed to send 8,000 men and 500 horses a day into Italy, without compromising or upsetting civilian train schedules.

Louis Napoleon Arrives in Genoa

The French army was a heady mixture of pride, panoply, and panache, eager to come to grips with the enemy and win fresh battle honors for the Second Empire. It had performed well in the Crimean War, and to many soldiers the very name Napoleon was a talisman of glory and a harbinger of victory. The infantry was dressed in shakos, long blue tunics, and red trousers and carried the Minie rifle-musket. Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard sported tall bearskin caps, hairy headgear that recalled the famous guardsmen of the First Empire. The hussars, lancers, and cuirassiers also wore colorful uniforms that echoed the country’s illustrious past.

Louis Napoleon lacked his famous uncle’s military genius, but he did have some talents as an artillerist. He had recently reequipped the Imperial army with bronze four-pounder, muzzle-loading rifled cannons that were far superior to the old smoothbores the Austrians were using. The rifled cannons fired a conical shell with great accuracy at ranges up to 3,500 yards—twice the range of their Austrian counterparts. Louis Napoleon landed in Genoa on May 12, greeted by a triumphant Cavour and acclaimed as a hero by cheering citizens. The emperor attended an opera, but soon left for his headquarters at Alessandria. By May 17 a Franco-Piedmontese army of 160,000 men and 400 guns occupied a 50-mile front just north of Alessandria.

Crossing the Ticino River

A skirmish at Montebello on May 20 pre-dated the first real battle, 10 days later, at Palestro. A 14,000-man Austrian reconnaissance force bumped into a Franco-Piedmontese army of some 10,700 men under the personal command of Victor Emmanuel. The Austrians were sent packing and forced to retreat. The king was a passive observer at first, but as the battle progressed his blood rose and he couldn’t restrain himself. Mounted on a gallant charger, he took part in the fighting at great risk to himself, winning an honorary corporal’s rank in the French 3rd Zouave Regiment for his troubles. It was the last time a European monarch ever personally led troops into battle.

Piedmont-Sardinia was now safe from invasion and the Austrians were in full retreat. The next order of business was the liberation of Lombardy and Venetia. The Ticino River was the first obstacle to allied designs, a swift, unfordable stream that marked the Lombardy-Piedmont border. Milan, the capital of Lombardy, was a much sought after prize, but there would be problems getting to it. The main road to Milan crossed the Ticino at the village of San Martino. The Austrians had fortified the crossing by building a powerful redoubt on the west bank of the river. As events unfolded, the Austrians abandoned the redoubt, but tried to delay French progress by blowing up the San Martino Bridge.

Unfortunately for the whitecoats, they succeeded merely in damaging two arches. French infantry could easily cross, and the bridge could be patched up enough to allow cavalry and artillery over the river. Seven miles to the north of San Martino was another possible river crossing at Turbigo. Mulling things over, Louis Napoleon ordered Maj. Gen. Jacques Camou, commander of the Voltigeur Division of the Imperial Guard, to march on Turbigo and secure a bridgehead. These orders were carried out in typical French style, with drums beating and a band playing martial airs at the head of the column.

Camou reached Turbigo without any opposition, and by the early morning of June 3, three pontoon bridges had been thrown across the Ticino. Camou was joined by Maj. Gen. Marie Patrice de MacMahon’s II Corps, and together they quickly brushed aside the weak Austrian opposition they encountered at Turbigo. Once the crossings were secured, Louis Napoleon decided to launch a two-pronged drive across the river. The ultimate objective was to clear the main road and advance on Milan. To this end, the Grenadier Division of the Imperial Guard would cross the Ticino at San Martino and continue on to the village of Magenta. MacMahon’s II Corps would cross farther south at Turbigo, accompanied by the Voltigeur Division of the Guard and the Piedmontese army.

If all went according to plan, both spearheads would reunite at Magenta. This was a dangerous, even foolhardy, maneuver—Louis Napoleon was dividing his army at a time when he had no idea where the enemy’s main forces were. There were no telegraph lines between San Martino and Turbigo, and the French would have to rely on old-fashioned horse couriers. The emperor was violating the most basic precepts of military science, a sign of both his inexperience and overconfidence. If one of his spearheads got into trouble, the other would be hard-pressed to come to its aid.

The Battle of Magenta

The Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard crossed the Ticino without incident, but soon clashed with Austrian forces who had positioned themselves behind the Naviglio Grande canal. There were two intact bridges over the canal, one at Ponte Nuovo, which carried the main road to Milan, and a railroad bridge just to the south. The Grenadiers attacked without hesitation, beginning the Battle of Magenta. It was a soldier’s battle, with little rhyme and less reason. Positions were taken at the bayonet, briefly held, then relinquished when opposing forces counterattacked. Louis Napoleon eventually arrived on the scene, but he was less commanding general than helpless observer of events seemingly out of his control.

More and more units were sucked into the bloody vortex, yet neither side seemed to gain the upper hand. Fighting was particularly fierce at Magenta, where every house and street was fiercely contested. Austrian sharpshooters, Jägers from the mountainous Tyrol, picked off French officers with chilling ease. The French Zouaves distinguished themselves at Magenta, colorful in their Algerian-inspired uniforms. This fame came at a high cost, however. One survivor noted that “squeezed in the narrow streets, our men seemed in their desperate attacks to take the houses corpse by corpse.”

The Austrians finally withdrew, giving the French a hard-won victory at the cost of 4,600 killed, wounded, or missing. Austrian casualties were even higher. The Piedmontese army, for its part, had not marched to the sound of the guns, and in fact had not even fired a shot, yet Italian newspapers trumpeted Magenta as a Franco-Piedmontese triumph. The French, having borne all of the fighting, were not pleased with their ally’s dubious claims, but any residual bad feelings were washed away in a tide of continuing victory. The Austrians fell back, establishing a new defensive line along the Mincio River. On June 8, Louis Napoleon and Victor Emmanuel entered Milan in triumph, capping liberation festivities by attending an opera at the world-famous La Scala. Lombardy was free, but the Austrians were far from defeated. The campaign would continue.

The Austria Reorganizes

On June 17, Louis Napoleon established his headquarters at Brescia, which was decorated in honor of the French emperor. Secretive as always, Louis Napoleon kept his staff in the dark most of the time. He would consult them from time to time, but even his closest aides had no idea of his plans. They complained that he “waged war like a conspirator.” In truth, the emperor was improvising the campaign as he went along, hampered by his inexperience and a crippling lack of reliable intelligence.

While the French emperor dithered, the Austrian army made an attempt to regain the initiative. Emperor Franz Josef reinforced and reorganized his army, then sacked the incompetent Gyulai and took personal command. Like his French counterpart, the 28-year-old Austrian monarch lacked experience, but he was determined to regain the advantage that Gyulai had so foolishly lost. The Austrian army, now numbering some 133,000 men organized into nine corps and supported by 400 guns, began the offensive by recrossing the Mincio and advancing west. At the same time, completely ignorant of enemy maneuvers, Louis Napoleon urged his columns eastward. The stage was set for a set-piece battle on the largest scale.

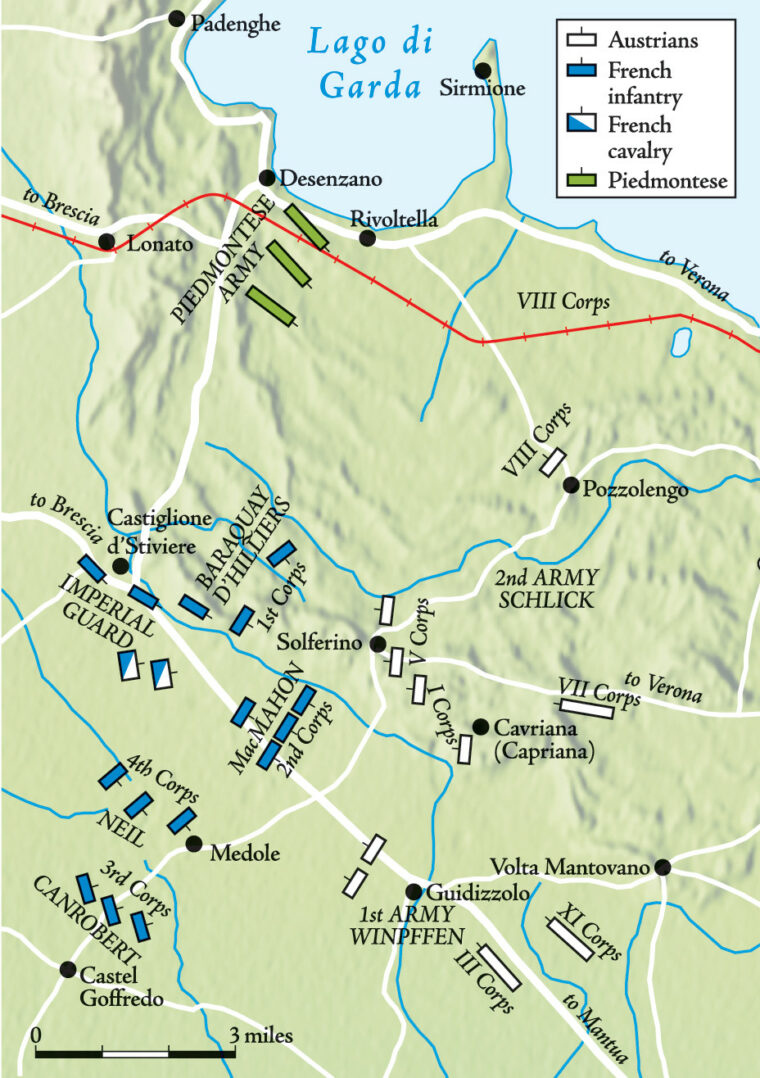

Stumbling into the Battle of Solferino

The two armies literally blundered into each other in the early morning hours of June 24. Leading elements of the French advance guard ran into Austrian pickets, forcing them back to their main line. The Austrian line was improvised but strong. They held the high ground, which would make them particularly hard to dislodge in a fight. The Austrian center was at Solferino, a village perched atop a series of hilly ridges that resembled a giant’s backbone. The village was in the shadow of Solferino Castle, a medieval fortress now crammed with Austrian infantry and artillery. Altogether, the battle front stretched some 15 miles, from Pozzolengo in the north, past Castiglione, Solferino, Cavriana, and Medole in the center, to Castel Grinaldo in the south.

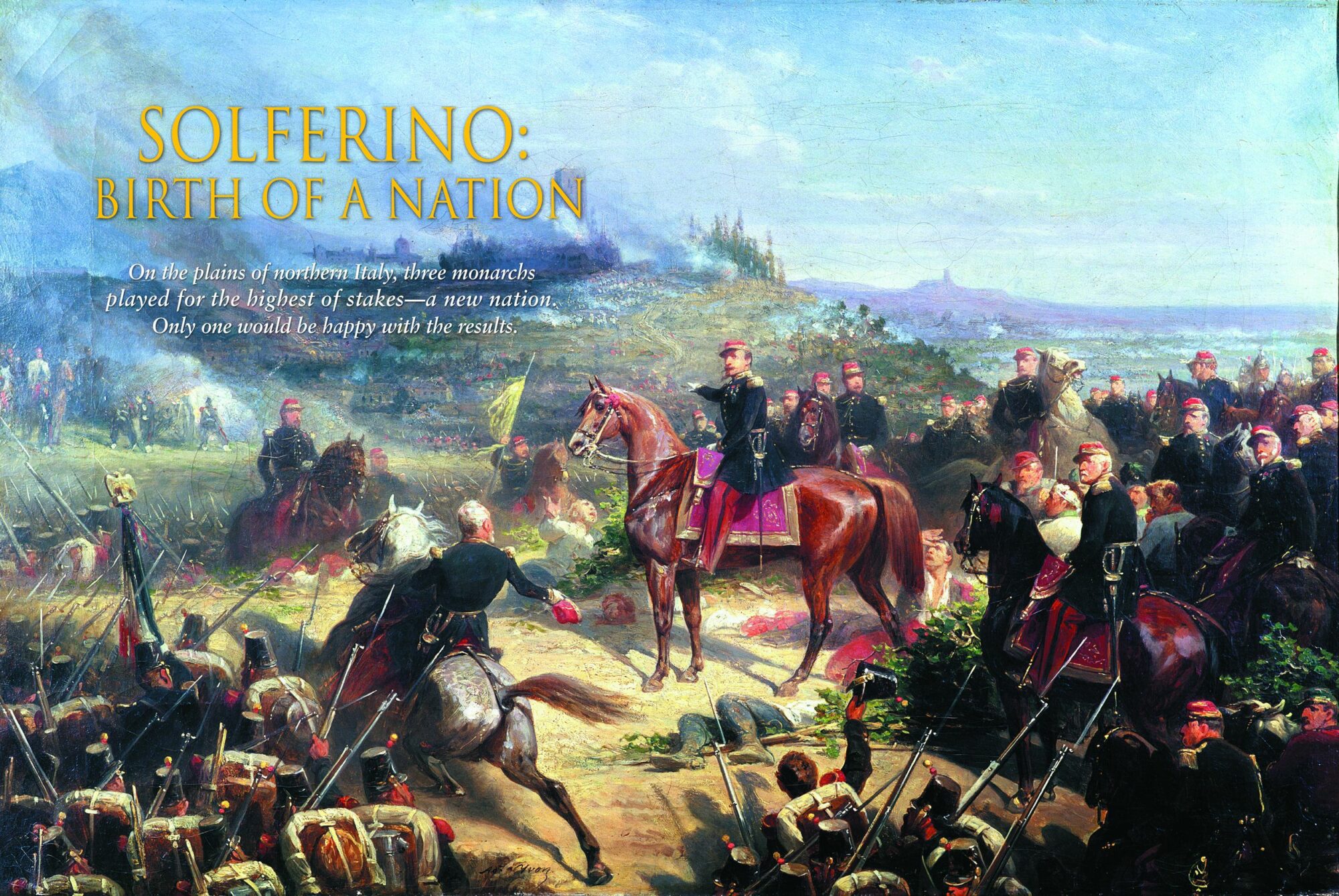

When Louis Napoleon began to receive reports of heavy fighting, he could scarcely believe it. Mounting his horse, he galloped over to the village of Castiglione and climbed its church’s bell tower for a better view of the impending crisis. From his perch he could clearly see skeins of white-coated troops massing on the heights from San Martino to Cavriana. Four miles west of Cavriana, Louis Napoleon could make out General Adolphe Neil’s French IV Corps hotly engaged at Medole.

Medole fell, but the French advance soon bogged down. A merciless sun beat down on friend and foe alike, and the dust-choked ravines and steep gullies were hard to climb under heavy Austrian fire. Louis Napoleon came down from the church tower and positioned himself near the center. Surrounded by his staff, the emperor chain-smoked cigarettes, a passive observer to the carnage he had helped to create.

Louis Napoleon’s Nerves

The battle degenerated into a soldier’s fight, brutal and bloody, where men tried to bludgeon their opponents into submission. There was no art in the battle, no finesse or intricate textbook maneuvers, just slaughter on an unprecedented scale. Louis Napoleon sat on his beautiful charger, surrounded by a glittering staff, but he was feeling anything but warlike. Clearly appalled by the horrors that assaulted his eyes, the emperor occasionally issued a terse order, but mainly he smoked cigarettes to ease his nerves.

Later, enemies in Paris had a field day describing his behavior, but they mistook nausea for cowardice. Louis Napoleon had shown his courage on many occasions, and he was so near the fighting now that an aide was killed by his side. But the emperor hated bloodshed and was sickened by the slaughter of his men. “Oh, the poor fellows,” he sighed. “Oh the poor fellows! What a terrible thing war is!” He was simply out of his element and lacked both the killer instinct and the indifference to physical suffering and pain of a great commander such as his uncle.

Battling for the High Ground

Louis Napoleon began to fear that Austrian reinforcements might attack his vulnerable right flank. There was no time to waste—the Austrians had to be defeated as soon as possible. The emperor decided on a frontal attack that would take the Austrian center at Solferino. The massive castle and village would be tough nuts to crack, but there was no other way to break the back of the Austrian defense. Louis Napoleon sent a message asking Victor Emmanuel for support. Unfortunately for the emperor, the Piedmontese monarch had his own hands full and turned down the request. Around 7 am, the Piedmontese advance guard had run into General Ludwig von Benedek’s Austrian VIII Corps in front of Pozzolengo. A fierce fight erupted, prompting Benedek to dig in on the heights west of San Martino. The Piedmontese army found itself fully engaged with an enemy that contested every foot of ground.

In the meantime, the superior French artillery hammered Solferino, shells raining down on the Austrians dug in on the heights. Gouts of flame and smoke blossomed on the dusty slopes, marking each hit, but it was clear the Austrians would not be dislodged by artillery fire alone. The long-suffering yet gallant French infantry would have to take the heights by bayonet and sheer guts. Louis Napoleon could see no other way to accomplish his goal. The Austrians were tough and resolute fighters, firmly positioned on the high ground. The French Grenadiers of the Guard had to manhandle their guns up a hill because the slopes were too steep for horses

On the right center a high slope was mantled by a copse of cypress trees. Cypress Hill was a key point, and its capture would lead into Solferino. Louis Napoleon ordered the Imperial Guard to take the hill. Fearsome apparitions in towering bearskins and greatcoats with red epaulettes on the shoulders, the Guardsmen clambered up the hillside under heavy fire, but nothing could resist their advance. After fierce hand-to-hand fighting, the Guardsmen took the hill and swept into Solferino. The Austrians gave ground but did not give up, transforming each building into a miniature fortress. The butchery continued.

The other side of Solferino was attacked by the men of the French I Corps. General François Achille Bazaine’s 3rd Division went forward, only to be repulsed by heavy fire. They quickly reformed and marched up the hill again, where they met such a withering fire that they had to retreat again. The dusty, scrub-covered slopes were carpeted by scores of blue-clad figures, some inert, some writhing in pain. Soaked in sweat, grimy with dust, and speckled with blood, the French soldiers formed again for a third try. Growing exhaustion, pain from wounds, and heat-induced thirst were numbed by the anesthesia of battle. As one soldier later recalled, “The smell of powder, the noise of the guns, drums beating and bugles sounding, it all puts life into you and stirs you up.”

The third time proved the charm, and French troops managed to take the position, fighting their way up the slopes into a walled cemetery. The Austrians stubbornly defended the position—there were probably as many corpses above ground as below. In time, however, the whitecoats fell back, unable to hold off simultaneous attacks by the 3rd Division on one side and the Imperial Guard on the other. Solferino fell at 2 pm.

The Austrian Retreat

The Austrian line was broken, and the two halves of the Imperial Army were in danger of being crushed in detail. Franz Josef wanted to continue the struggle, but he was forced to accept the inevitable. A general retreat was ordered, with the remains of the Austrian army retiring behind the Mincio River. It was now around 3 in the afternoon, and gathering clouds produced a torrential thunderstorm that soaked victor and vanquished alike. Thunder mixed with the last salvos of artillery to produce a fearful din. The rain broke the almost tropical heat, but it also impeded allied pursuit of the retreating Austrians.

A Bloody Battlefield, a Shaken Emperor, and a New Nation

The next day dawned on a scene of unprecedented horror. The French had lost approximately 11,000 dead, wounded, or missing, while the Piedmontese had lost some 5,000. Austrian casualties were even greater—some 22,000. Henri Dunant, a civilian observer who later founded the International Red Cross, recalled, “Bodies of men and horses covered the battlefield; corpses were strewn over roads, ditches, ravines, thickets, and fields; the approaches of Solferino were literally thick with dead. Here and there were pools of blood.”

Louis Napoleon had won the great battlefield victory he had sought for so long, but the horrific triumph left a bad taste in his mouth. His response to Solferino was typically laconic; he telegraphed his wife Eugenie merely that he had won a “great victory.” The French emperor was shaken and nauseated by the carnage. He insisted on visiting a barn that had been converted into a field hospital. It was a vision of hell more terrible than the torments described in Dante’s Inferno. Hundreds of wounded soldiers lay packed together, uniforms torn, filthy, and caked with blood. The stench of gore and excrement was overpowering. While the emperor watched, overworked surgeons casually tossed amputated arms and legs into a corner of the barn. The mound of bloodied flesh grew ever higher with each operation. Louis Napoleon quickly ended his tour of the hospital, emerging with reddened eyes and a deathlike pallor. Profoundly moved, the emperor went to the side of the barn and vomited, while his staff discreetly looked away. He had had enough, in more ways than one.

The Austrians retired into a region called “the Quadrilateral,” a fortified area that included Mantua, Peschiera, Verona, and Legnano. Taking this position would be no picnic. With every likelihood that there would be battles even bloodier than Solferino, Louis Napoleon asked for an armistice, then personally met with Franz Joseph at Villafranca. A peace treaty was hammered out that granted Lombardy to Piedmont-Sardinia but fell far short of Napoleon’s earlier pledge to liberate Italy “from Alps to Adriatic.” The Piedmontese felt betrayed, but they had to agree to the terms.

Events soon outran Louis Napoleon’s improvised peace. Piedmont-Sardinia annexed Tuscany, then quickly took over the Grand Duchies of Lucia, Modena, and Parma. By 1861, most of the papal states and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilys had also fallen into line. Italy was finally united under Victor Emmanuel, as the canny Cavour had hoped and planned. At Solferino, the French had done the lion’s share of the fighting, but the Piedmontese had won the lion’s share of the prize—nothing less than a new nation.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments