By Jerome M. Baldwin

By the 1930s the security Hong Kong had enjoyed since its acquisition by the British Empire in 1842 was a memory. The supremacy of the Royal Navy was seriously threatened by the rise of Japan as a world power in the region; the island was now within range of artillery from the mainland; and the threat of air attack now loomed as well. The British, realizing the precariousness of the colony’s position, wrote it off as an indefensible outpost of the Empire and maintained no large defense force there.

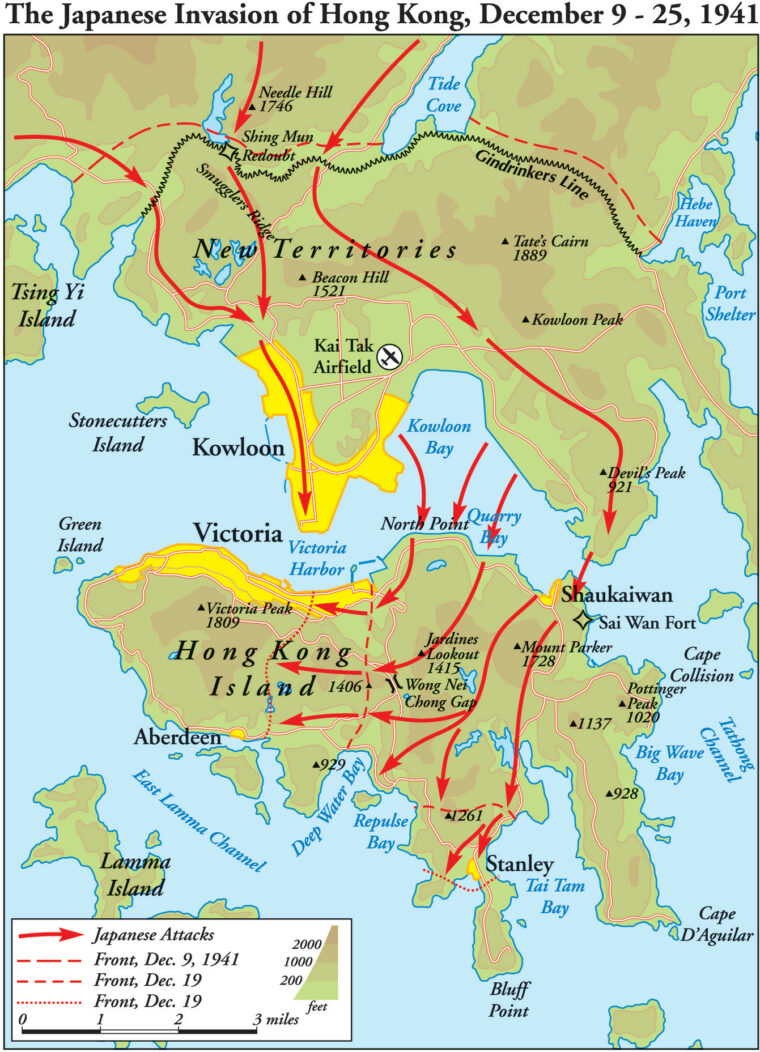

The situation grew more precarious in July 1937, when the Japanese invaded China. In December the British authorized two more battalions to be sent to supplement the four infantry battalions already there and, over the course of the following year, considered different options for Hong Kong in the event of a Japanese attack. It was unthinkable to simply give up even a mere outpost without a fight, so the plan called for a delaying action on the Gin Drinkers Line, allowing enough time to destroy the oil storage and dock facilities in Kowloon, followed by a strong defense of the island until a relief force could arrive from Singapore.

The threat continued to grow. When the Japanese captured Canton from the Nationalist Chinese in October 1938, the Chiefs of Staff in London were certain they would attack Hong Kong but did not consider an attack to be imminent. According to them, the Japanese lacked the resources to wage war against the British Empire, they were worried about how the Americans would react if they did attack Hong Kong, and they had to contend with the threat of Soviet Russia from the north.

A “Tough Nut to Crack”

In September 1941, Maj. Gen. A.E. Grasset finished his tour as commander in chief of Hong Kong, handing the reins to Maj. Gen. C.M. Maltby. Grasset was a Canadian, and he decided to return to England via Canada, where he visited his old friend from Royal Military College, Lt. Gen. Henry Crerar, now chief of the Canadian General Staff. While they talked, Grasset mentioned that two more battalions in Hong Kong would enable the colony to hold out for an extended period of time against a Japanese attack. Crerar later denied that Grasset made any outright request for Canada to provide troops, but there can be little doubt that Grasset planted the seed that eventually resulted in Canada providing them.

Arriving in England, Grasset reported to the Chiefs that Hong Kong’s defenses were strong, morale was high, and the colony would be a “tough nut to crack.” He then reported that if Canada were asked nicely, it would provide another two battalions for the garrison there, which would bring it to the strength authorized, but never implemented, in December 1937. Initially the response was negative, but soon even Churchill, who hitherto had been staunchly against any more troops being sent to Hong Kong for all the sound reasons the British had known for years, came around.

With that the wheels were set in motion, and the Dominions Office submitted a formal request in a cable to Ottawa on September 9. Through misleading words and omissions it gave the unmistakable impression that the colony could be held indefinitely when the plan that required the quick arrival of a relief force for the garrison’s salvation had not changed. With no intelligence service of its own then, Canada was completely reliant on the British, and that reliance would play heavily on events.

Canadian Associate Defence Minister Major C.G. Power, assuming Crerar thought the mission to be militarily sound but never asking Crerar if he thought it was, gave his approval. Prime Minister William Mackenzie King, an anti-imperialist, was wary of taking Power’s word for it and insisted that the matter be submitted to the Defence Minister, Colonel J.L Ralston, on holiday in the United States.

“No Military Risk”

Upon receiving the message, Ralston sought the advice of Crerar who told him the operation had “no military risk.” Ralston then gave the request the green light, after which King did as well. Canada confirmed its agreement in its official reply October 2, and the ill-fated mission got underway.

Had there been more time to prepare, someone might have realized the potential disaster that was looming. Britain, however, wanted the force to set sail by the end of October, a ridiculously short period of time to prepare for such a large operation. The breakneck pace of the mission’s organization was the harbinger of serious oversights and mistakes to come.

The two battalions selected were the Royal Rifles of Canada, under Lt. Col. W.G. Home, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers, under Lt. Col. J.L.R. Sutcliffe. The most combat-ready units were needed in Europe, and both units were designated Class C, “not recommended for operational deployment at present.” Both had finished tours where no shooting occurred, the Rifles in Newfoundland and the Grenadiers in Jamaica. Although the danger signs were abundant, Crerar fully expected that Hong Kong would require more of the same type of duties they had both been performing. The force was designated C Force and placed under the command of Brig. Gen. J.K. Lawson on October 11, the day Britain requested that a brigade headquarters be sent as well, to which Canada agreed.

C Force sailed on the troopship Awatea from Vancouver on October 27. The Awatea could not accommodate all 1,975 men, so 150 of them had to be crammed onto the naval escort, the merchant cruiser HMCS Prince Robert. Through incompetence, their vehicles did not leave with them and would never reach Hong Kong.

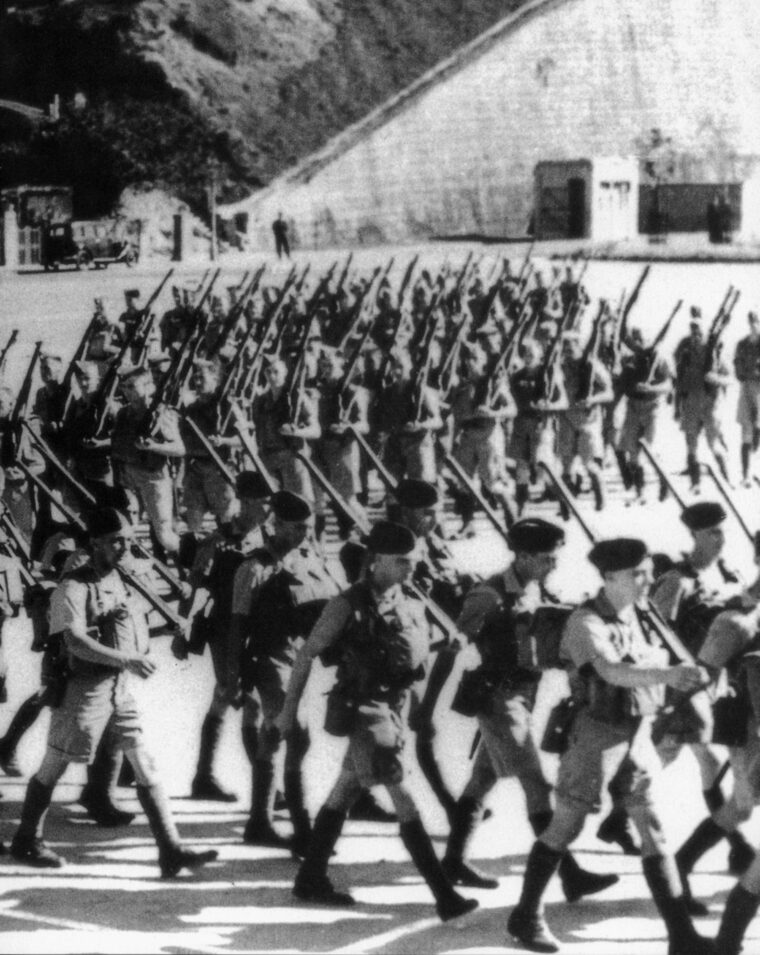

The Awatea docked in Hong Kong on November 16, 1941. As they marched to the Shamshuipo Barracks in Kowloon cheering crowds lined the streets waving Union Jacks. The colony seemed to feel more secure with the Canadians’ arrival, even though 50,000 combat-experienced Japanese soldiers of Maj. Gen. Takeo Ito’s 38th Division were massed on the border.

14,000 Defenders

With the Canadians’ arrival, Maltby decided on a defensive plan of two brigades, one on the mainland and one on the island. The Canadians were assigned to the island along with the 1st Battalion Middlesex Regiment, all under the command of Lawson. The Mainland Brigade consisted of a Royal Scots battalion and two Indian Army battalions under Brig. Gen. Cedric Wallis. Altogether, with the arrival of the Canadians, 14,000 men had been assembled to defend Hong Kong.

Maltby’s battle plan called for a delaying force to destroy bridges and culverts, slowing down the Japanese attack force before falling back on the Gin Drinkers Line. It was expected that the Gin Drinkers Line would hold for at least a week, providing ample time to destroy the Kowloon dock facilities and oil tanks, denying them to the Japanese. The Devil’s Peak redoubt, on the eastern side of Kowloon, was to hold out indefinitely.

The Battle Begins

At 8 am on Sunday, December 8, the meager air defense Hong Kong had was destroyed in a bombing raid. Shamshuipo Barracks was hit as well, wounding four Canadians and killing several Chinese outside. Almost simultaneously, Japanese soldiers crossed the border. The delaying force destroyed culverts and bridges according to plan, but the Japanese spanned the gaps with bridge replacements they had brought with them.

Just before midnight on the 9th, Maltby ordered C Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers over to the mainland to participate in a counterattack on the Shing Mun redoubt, the lynchpin of the Gin Drinkers Line, which had already been lost. The Royal Scots, badly mauled, could not mount a counterattack, however, and the Canadians were ordered behind the Scots’ left flank to cover the Castle Peak coastal road and the southwestern slope of Golden Hill, where the Scots had withdrawn. By 6:30 pm they were beginning the withdrawal to the mainland behind the Royal Scots, slipping away in the darkness to head back to Kowloon. They had only exchanged a few sporadic shots with some Japanese scouts—the first combat action for Canadian soldiers in World War II— before crossing back to the island.

With the sinking of the British battlecruiser Repulse and battleship Prince of Wales off Malaya on the 10th, all hope of relief in the foreseeable future was gone. Despite this, on the morning of the 12th a Japanese invitation to surrender extended to the colonial governor, Sir Mark Young, was rejected outright.

Meanwhile, Maltby prepared the island defenses for the inevitable assault. The garrison was divided into East and West Brigades, Wallis commanding the East while Lawson commanded the West. Maltby’s plan called for shoreline defenses to halt any Japanese landing, with the Canadians just behind in the interior to take care of any breakthroughs the Japanese might make. Demolitions carried out before the withdrawal from the mainland were expected to delay Japanese artillery being brought up for weeks. However, by the 16th the Japanese were hammering the island with heavy artillery and aircraft, particularly the eastern shoreline.

Japanese Boots on the Island

On the 17th another Japanese delegation approached the British with a second offer for them to surrender. It was refused, and the next day, just after dark, the Japanese started crossing over in anything they could find that could float, some even swimming. They struck precisely in the waterfront region that Maltby had said they were least likely to strike, between North and Lye Mun Points. The 229th Regiment landed at Sai Ki Wan and Lye Mun with orders to take Mount Parker; the 228th came ashore at the Tai Koo docks, headed for Mount Butler, while the 230th Regiment landed around North Point and made for Jardine’s Lookout.

The Rajputs defending the eastern shoreline quickly collapsed, and the Japanese swarmed ashore, infiltrating quickly inland. Hearing the gunfire north of him, Royal Rifles C Company commander Major W.A. Bishop ordered two of his three platoons to investigate. After unsuccessfully trying to retake the Sai Wan Fort, they withdrew, inflicting heavy casualties on the Japanese as they headed down the coast toward the Tai Tam Gap to keep from being cut off should Mount Parker be captured.

At 9:30 pm, Lt. Col. Home was ordered by Wallis to send a reinforced platoon from Headquarters Company under Lieutenant G.W. Williams to occupy the peak of Mount Parker and “prevent the enemy from doing likewise.” The Canadians did reach the peak but were soon overwhelmed in a hopeless fight against superior numbers and driven back. Williams was killed. At 2 pm, another platoon under Lieutenant C.A. Blaver was ordered to reinforce Williams’s platoon but was “unable to reach position and was forced to retire at 0900 hours owing to the high ground on Mount Parker being occupied by the Japanese.”

Meanwhile, things were not going much better in the West Brigade half of Hong Kong. This territory held the vital Wong Nei Chong Gap, where all roads on the island led, most notably the north-south Repulse Bay road. Sutcliffe, under Maltby’s orders, sent a platoon under Lieutenant G.A. Birkett to occupy and hold Jardine’s Lookout, which overlooked the Wong Nei Chong Gap. It was the same story that was happening to their comrades in East Brigade. They reached the peak around dawn but soon found themselves facing a Japanese battalion with heavy artillery and were driven off with heavy losses, including Birkett.

The Fight for Mount Butler

Lawson had moved the brigade headquarters from the Wanchai Gap right up to the front line in the Wong Nei Chong Gap, inside some steel-doored antiaircraft shelters that were hewn from the rock on each side of the main north-south road. Again, under orders from Maltby at 2:30 am on December 19, Sutcliffe ordered A Company, Winnipeg Grenadiers to make an attack on Mount Butler. It is possible that in the chaos of battle Mount Butler was confused with Jardine’s Lookout, which was between the Grenadiers and Mount Butler. Attacking Mount Butler would have required Jardine’s Lookout to be in Allied hands, but A Company somehow became divided. However, a group led by Company Sgt. Maj. J.R. Osborn was able to capture the summit of what was recorded as Mount Butler by bayonet charge just before dawn.

At around 10 pm, Sergeant W.J. Pugsley “noticed our troops on Mount Butler were falling back and almost immediately recognized Japanese troops in large numbers coming over Butler. CSM Osborn now took charge of two Bren guns of my platoon and directed covering fire of the withdrawal of the party. He was cool and steady at all times and greatly helped the spirit of the men. All this time we were under fire from the right flank and, at about 1300 hours, Captain Tarbuth, who was being carried by Private J. Williams, had to cross a slight rise in the ground and both were killed by machine-gun fire; and the Japs opened up on our right Bren gun, killing the crew and knocking out the gun.

“We still continued resistance with the one gun and rifle fire, under the direction of CSM Osborn and Major Gresham, trying to get back to Wong Nei Chong, but discovered that numbers of Japs had worked round behind us and that we were cut off. At last, about 1515 hours, Major Gresham decided to surrender, stepped out of the depression with his hands up, and was immediately shot down and killed.

“By this time the Japs had got close enough to throw grenades into our positions, and CSM Osborn and myself were discussing what was best to be done now when a grenade dropped beside him.

“He yelled to me and gave me a shove, and I rolled down the hill and he rolled on to the grenade and was killed. I firmly believe he did this on purpose, and by his action saved the lives of myself and at least six other men who were in our group. This happened at about 1530 hours. Within the next ten minutes the Japs rushed our position and took the remnant of the company prisoners.”

For his selfless act of heroism, 41-year-old Osborn became the first Canadian awarded the Victoria Cross in World War II.

Hong Kong Surrenders

The Japanese closed in on Lawson’s shelters, where, surprisingly, the telephone was still functioning. At 10 am, Lawson reported to Maltby that the enemy was firing point blank on his shelter and that he and some of his staff were going outside to fight it out. With guns blazing from both hands, Lawson and his men shot it out with the Japanese before he was killed, the area around his shelter littered with bodies of the enemy.

As the C Force war diary recorded, conditions in the gap grew steadily worse. “The position was being fired upon from all sides. It might be compared with the lower part of a bowl, the enemy looking down and occupying the rim. The main road running through the position was cluttered for hundreds of feet each way with abandoned trucks and cars. The Japanese were using mortars and hand grenades quite heavily. Casualties were steadily mounting, but at the same time reinforcements were trickling in the form of stragglers, so that at the end of the day, while the killed and wounded were approximately twenty-five, the effective fighting strength was about the same.”

By the 20th, things had gotten very desperate. “Casualties mounting, over 30 wounded in shelters and water very scarce.” Amazingly, the men in the gap managed to hold out until the morning of the 22nd, when the steel doors were blown in with a 2-inch gun. Shortly afterward, they surrendered.

Even before the fall of the Wong Nei Chong Gap, the Japanese had managed to get around it and by nightfall of the 19th were looking down on the Repulse Bay Hotel at the junction of the coast road and the north-south road that ran through the gap. They soon brought artillery to bear, effectively cutting the Allied garrison in two while the gap defenders still fought on.

The end was near for Hong Kong. For the next three days the pattern continued—the wasting of men in futile and useless actions that could never hope to change or even significantly delay the final outcome of the battle, ordered by commanders who seemed to grow more out of touch with reality with every passing hour. On Christmas morning Wallis ordered a company-strength attack on a ridge above Stanley village, ignoring the protests of Lt. Col. Home that it would be another senseless waste of men. In the action that followed, D Company of the Royal Rifles was wiped out after a bayonet charge and vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Around 6:30 pm, A Company of the Royal Rifles had just begun an attack up the main road in Stanley when the enemy guns fell silent and a car flying a white flag appeared carrying two British officers. They brought the news that the colony had been surrendered about three hours earlier.

An Unanswerable Tragedy

The fighting was over, but the killing was not. The horror of Japanese occupation and captivity was only beginning for the defeated at Hong Kong. In St. Stephen’s Hospital in Stanley, the Japanese bayoneted 70 Allied soldiers in their beds and brutally raped the nurses there, many of them to death. It was only one example of numerous savage atrocities committed by Japanese troops against soldiers and civilians alike after the surrender.

The Canadians had suffered badly: 783 men and 59 officers killed or wounded in the battle. Another 195 would die in the miserable conditions behind Japanese wire. Altogether, of the 1,975 Canadians who were sent to Hong Kong 555 would not return, including the Grenadiers’ commanding officer, Lt. Col. Sutcliffe, who died as a POW. Many of those who did make it home were broken in body and spirit for the rest of their lives, which were often shorter than what they would have been because of the years of malnourishment, overwork, and disease.

In Canada, no one ever really had to answer for the tragedy of Hong Kong, including the man who had said it had no military risk, Lt. Gen. Henry Crerar. In the months to come he would be instrumental in pushing ahead Operation Jubilee, the disastrous raid on the French coastal town of Dieppe. Later, he would be promoted to full general and given command of the First Canadian Army in Europe after D-Day.

Jerome M. Baldwin is a resident of Amherstburg, Ontario, Canada. He is a veteran of the Canadian Army, having served as a fire control systems technician.

Hi All Historians;

It is really strange that At my local library there isn’t a single book on the Illustrious 4-Star General; “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell (Joseph Warren).

Or any information about the local Hong-Kongers who actually fought in the Battle.

Also; the Australian “Z”-Force. Who participated in the Theatre Of War in WWII.

Jack Wong Sue who; wrote Blood On Borneo and Ghost Of the Alkimos.

Much of the History of WWII is written from the prospective of the Western Imperial Powers and from “White” Authors as opposed to anything

from the People from the Far East itself!

I am glad that there is now a generation of youngsters in H.K. who have never experience Colonial Western OR Japanese Aggressive Rule, Period!