By M. Foster Farley

After defeating the Confederates at Chattanooga, Union Gen. William T. Sherman, in May 1864, with an army of approximately 100,000 men, and using the Western and Atlantic Railroad as his line of supply, began his march to Atlanta. The Georgia capital was an essential railroad hub as well as a center for much of the Confederacy’s heavy industries, cannon, powder and other war necessities, thus making an inviting target. But Sherman would have a long and thin line of supply stretching all the way back to the Ohio River.

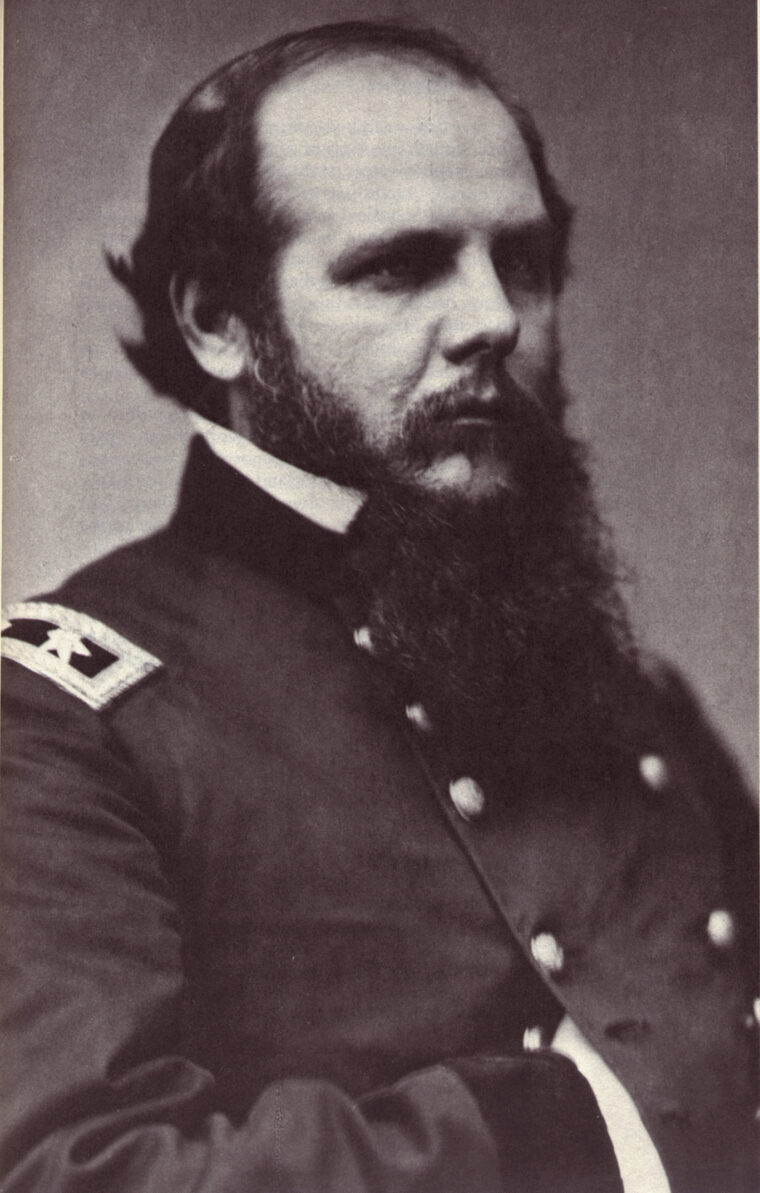

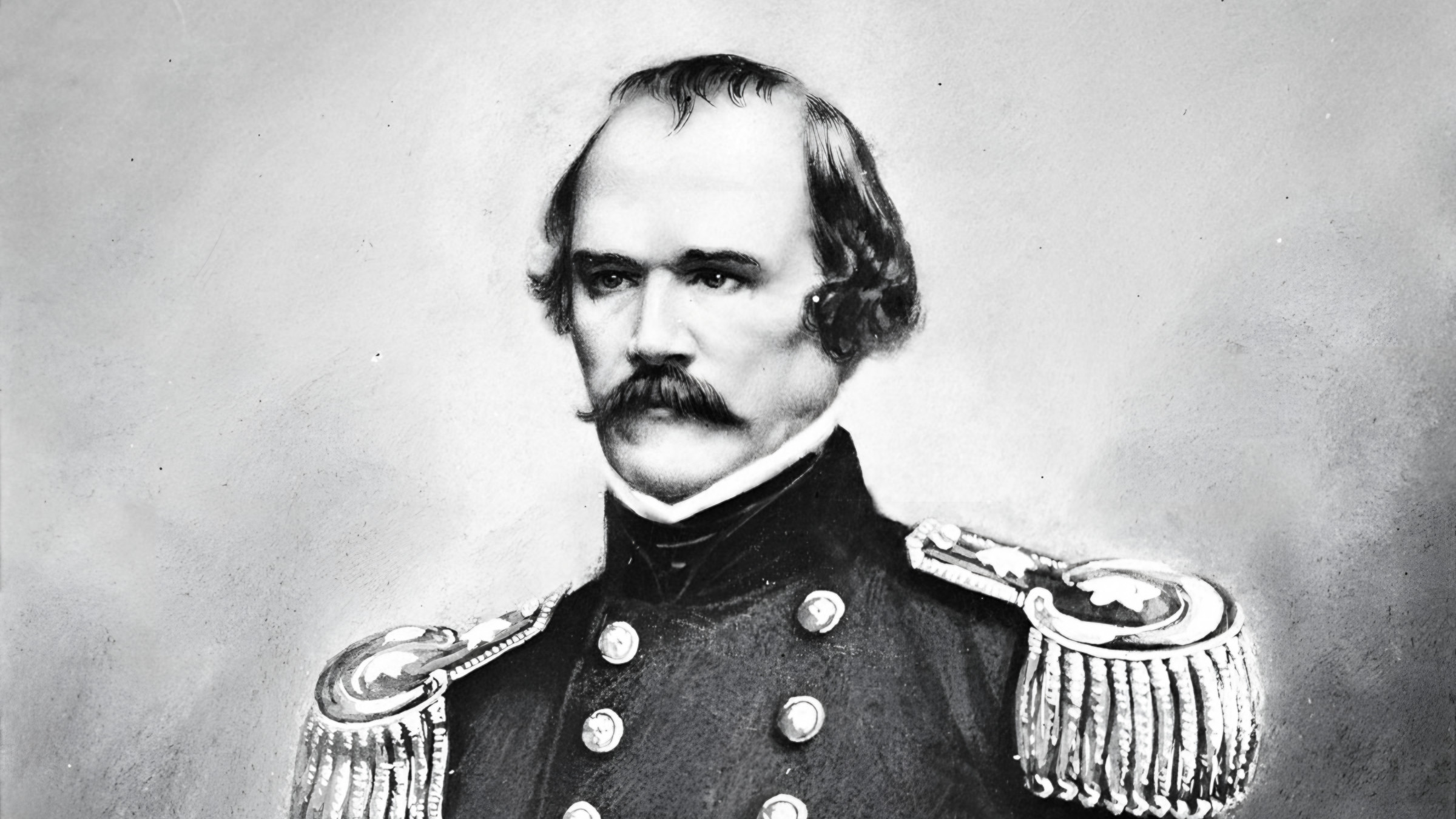

Facing Sherman was the Army of Tennessee, of some 60,000 men, commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who had replaced Gen. Braxton Bragg when the latter had become President Jefferson Davis’s chief military adviser. Sherman proceeded down the rail line, flanking Johnston along the way by repeatedly stretching his lines farther than Johnston was able to do and forcing the Confederates to fall back. By July 9, the Union forces were six miles from Atlanta. President Davis, who did not get along with Johnston—the two had quarreled for most of the war—listened to Bragg, who urged that Johnston be removed. Davis then unwisely appointed 33-year-old Kentucky-born Texan John Bell Hood to command.

Hood, a graduate of West Point, was 6-foot-2 with a long flowing beard. He had lost the use of an arm at Gettysburg, and one of his legs had been amputated on the battlefield at Chickamauga. Nonetheless he was full of the offensive spirit. He had served in the old army in California and Texas. He had also seen the “most spectacular advance in rank of any officer in the Confederate service.” He had participated in many battles, serving in turn as a regimental, brigade and division commander in the Army of Northern Virginia. When he superseded Johnston, he had been commanding one of Johnston’s corps. But Hood had never been an independent commander,

and felt uneasy taking charge of the Army of Tennessee in one of the greatest crises of the war. Unfortunately his officers doubted his competence, and were lukewarm in their support of this “rash young general.”

Hood did what he could, but he could not halt Sherman’s juggernaut. He was repelled by Sherman in the several battles of Peachtree Creek, Ezra Church and Jonesboro. Sherman, having cut Hood’s supply line by seizing the only railroad available to him, forced the Confederate commander to evacuate Atlanta on September 1, and the Federal Army occupied the Georgia city the next day.

What would Hood do now? Because Sherman’s line of supply and communication was spread for many hundreds of miles northward, Hood reasoned that if he could break that long connection, the Union general could be isolated. Severing the supply line meant marching north, and he did so. At first Sherman sparred with him, but after six weeks thought better of it and decided that a march to the sea through the gut of the Confederacy would have better effect than chasing Hood. Sherman thus cut himself off from his supply line and headed for Savannah. Hood turned north in hopes of isolating Sherman—or drawing him northward—occupying western Tennessee, marching to the Ohio River, and destroying any Federal force in his way.

Before beginning his march north, Hood telegraphed Richmond asking for reinforcements, but the Confederate government replied that “no other resources remain.” In effect, President Davis “neither approved nor disapproved” of Hood’s battle plan. Still, Hood cherished the remote hope of victory for the South. He would begin by calling Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and his cavalry to join him in northern Alabama, and then together they would march into Tennessee to revive the Confederate chances for independence. In a sense, Hood’s proposed thrust into Tennessee was an immense gamble. If the Federals could not defeat Hood, Sherman’s march to the sea might turn into the worst disaster of the war for the Union; if the Federals could defeat Hood, Sherman’s march would seem a tremendous success and a likely death knell for the Confederacy.

In any case, Sherman had given Hood an opportunity—at least for a time—to fight his equal in numbers. He had sent Gen. George Thomas’s back to Tennessee to counter Hood. When Hood began his move—with about 40,000 men—Thomas’ forces were scattered, his only reliable force being that of Gen. John M. Schofield, posted at Pulaski some 65 miles south of Nashville with 27,000 men. If Hood could cut off Schofield before he could reach Thomas, consolidating forces at Nashville, Thomas’s chances of creating a superior army would be cut in half.

With Tennessee recovered for the South, Hood could refit his force at Nashville and then invade Kentucky. Once in that state, and even across the Ohio River, he could be a rallying point for Northern antiwar Copperheads. Hood might then cross the Cumberland Mountains and fall upon General Grant from the rear thus coming to Lee’s aid. Despite this fantastic scheme, Hood had none other in mind.

Leaving cavalry Gen. “Fighting Joe” Wheeler in Georgia to keep an eye on Sherman and give him as much trouble as possible, Hood’s Army of Tennessee headed for Alabama. It comprised 35,600 men, including infantry, artillery and cavalry. It had been badly led except for the time that Joe Johnson was its chief. But the Army of Tennessee had never refused to fight the enemy, and now, although its confidence in its commander was none too ardent, spirits were high. And it would be fighting in its namesake, Tennessee.

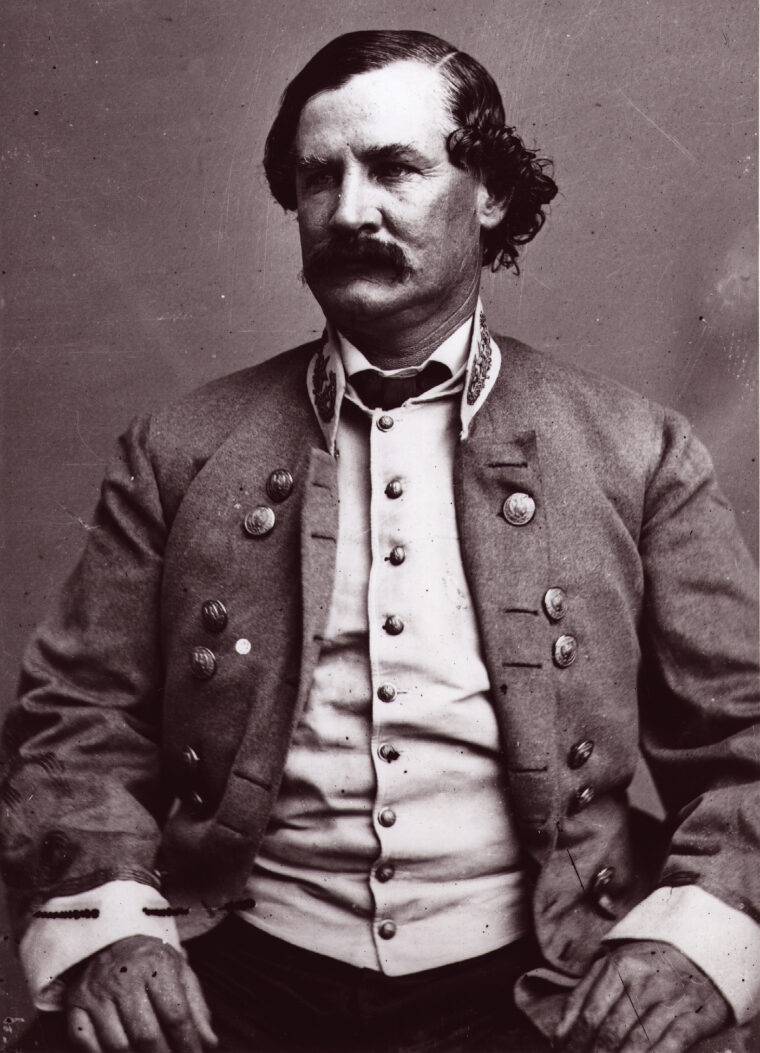

Hood waited in Florence, Ala., for Forrest who, upon his arrival, assumed Hood’s cavalry. Forrest—with his three thousand men, plus Gen. Henry Rootes Jackson’s two thousand, made a very effective cavalry arm. The next day the Confederate horsemen swept forward at the head of the Army of Tennessee in the race to cut off Schofield before he could join Thomas at Nashville.

When Forrest joined the Army of Tennessee, his presence could have helped Hood in many ways—if Hood had used him to the fullest; but the Texan failed to sufficiently utilize the great tactician. Forrest was probably at the time one of the most underrated generals in the Southern service. He was not a soldier before the war, but like Oliver Cromwell two hundred years earlier, he was a great leader of men. Forrest could have led infantry as well as cavalry. In the last year and a half of the conflict, for example, he used horses as “mounted infantry.” Moreover, he could recruit men when other leaders failed to do so, and reap supplies where others had failed. The morale of his men at the end of the war was still “stiff with courage.” Later, when Robert E. Lee was “asked who was the greatest soldier” in the Southern army, he replied, “a man I have never seen sir. His name is Forrest.”

In any event, by the time Hood had crossed into Tennessee, General Thomas was back in Nashville assembling an army of approximately 50,000. Halfway back to Nashville from Pulaski at the town of Columbia was Schofield and two army corps. It seemed that Hood was blocked from intervening between Thomas and Schofield, the better to fight and reduce them in detail. But then Hood brilliantly stole a march on Schofield, sweeping behind him in anticipation of assailing the Federals at Spring Hill as they retreated up the pike toward the town of Franklin on their way to Nashville. But in the confusion of evening and night, an attack on the pike was never launched. Through the darkness of November 29, 1864, Schofield’s army slipped up the turnpike toward Franklin, within easy range of the strangely hesitant Confederates. At daylight on November 30, Schofield entrenched his forces at Franklin on the south side of the Harpeth River, the last major river crossing south of Nashville, while he worked to get his wagon trains across.

Although the morning of November 30 was promising to be a splendid Indian summer day, pleasantness was far from the table at which Hood and his generals breakfasted (at the Spring Hill mansion of one of the Army of Tennessee’s majors). Hood was let down and annoyed by the failure of the previous night. He berated his generals, accusing them of neglect. He was angry enough to seek some sort of vindication.

It would arrive at Franklin, where Schofield had his back to the river. South of the town lay a broad plain, mainly flat and uncovered, stretching two miles to Winstead Hill, a tall rise astride the Franklin & Columbia Turnpike, which ran north–south up the plain’s center. Lewisburg Pike on Hood’s right and Carter’s Creek Road on his left also led to Franklin.

By noon that same day, Schofield’s men had fortified themselves in a large crescent-shaped defense. General Cox with the 23rd Federal Corps held the left and center, covering the Columbia and Lewisburg pikes. General Kimball’s division of IV Corps was on the right. Both flanks rested on the Harpeth River. General J.T. Wood’s division of IV Corps, with some artillery, was moved to Fort Granger (on the north bank of the Harpeth) to guard the wagon trains and cover the flanks should the Confederates attempt to cross above or below the Union position. Also on the north bank of the Harpeth, Gen. James H. Wilson with his cavalry took his position to prevent Forrest from crossing and attacking the Federal rear. On a slight rise of ground about a half-mile in front of the main federal works, Schofield had entrenched two of Gen. George D. Wagner’s brigades to serve as a skirmish line. They were instructed to remain there until—should he attack—Hood advanced in force, then retire to the principal defenses. Inside the main Union battlements was a one-story dwelling known as the Carter house, accompanied by a brick smokehouse and a wooden cotton gin.

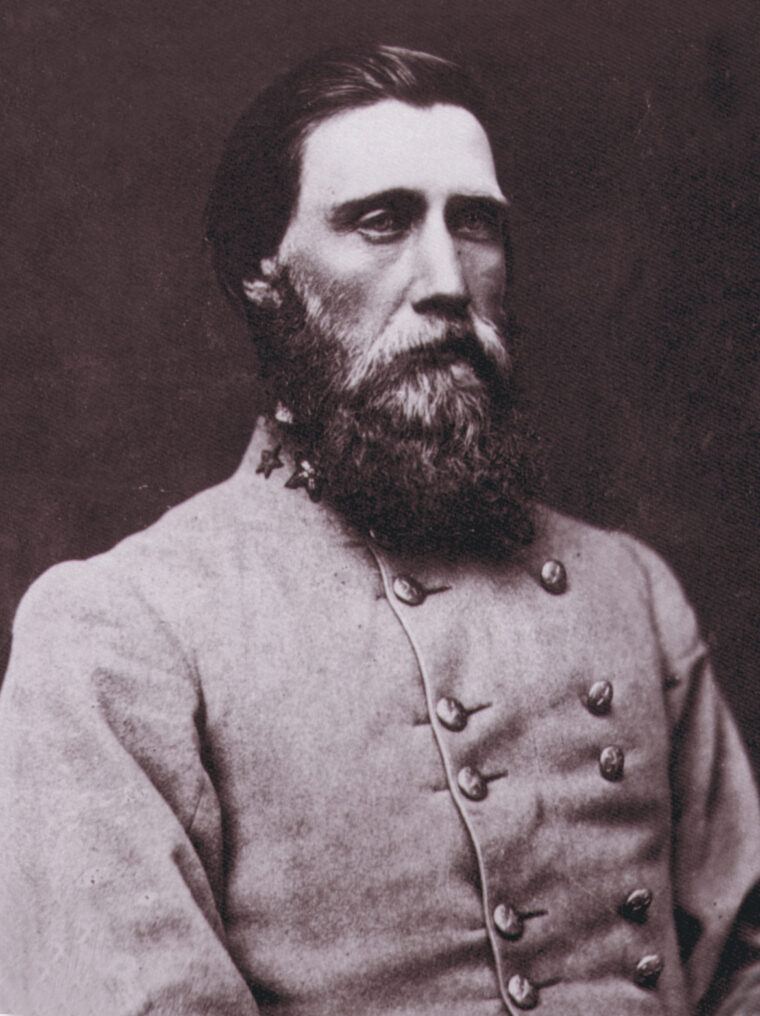

By two in the afternoon, Confederate infantry began to appear on the rim of the hills south of Franklin. At Winstead Hill, Hood and his generals gathered to survey the situation. All the generals except Hood were convinced that it would be suicidal to hurl a frontal assault across two miles of open ground against the prepared breastworks. Forrest, who knew the country better than Hood, tried to convince his chief that he could cross the Harpeth at one of the several upstream fords and fall upon him from the rear. Lieutenant General Benjamin F. Cheatham, in command of one of Hood’s corps said, “I do not like the looks of this fight, the enemy has an excellent position and is well fortified.” Major General Patrick Cleburne, in command of a division in Cheatham’s corps, and others, also advised against a direct attack; they believed such an assault would result in a frightful and senseless loss of life.

But Hood was not to be dissuaded. He instructed Cleburne to “move on the enemy” and inform your men “not to fire until you drive the Federal skirmishes from the first line of works in your front.” Then “press them and shoot them in the backs.… Then charge the main works.” Cleburne replied prophetically to these orders with the words, “General I will take the works or fall in the attempt.”

Cleburne, called by some the “Stonewall of the West,” was a native of County Cork, Ireland, born there March 17, 1828. After attending Trinity College, Dublin, with the intention of studying either medicine or pharmacy, he left because he couldn’t master Latin or Greek. From 1846–1849 he served in the 41st Regiment of Foot of the British Army and attained the rank of corporal. On September 27, 1849, Cleburne purchased his discharge and migrated to the United States along with his brother and sister. He was soon employed in a drug store in Cincinnati, and by April 1850 had settled in Helena, Ark., working in a drug store with Dr. C.E. Nash. Before the decade was over he had studied law and had been admitted to the bar by 1856.

When the War Between the States began, Cleburne enlisted as a private and rose rapidly in rank. As one comrade said of him, “Cleburne rose to be a military authority in our army. He knew the very rudiments of fighting and had the genius to use his knowledge. He was always ready and watchful, and was never depressed, loved by his good men, and feared by his bad men, and trusted by all. He was indomitable in courage, skillfully headlong in attack, coolly strategic in retreat.…

“He was obedient to the letter, capable in any crisis, modest as a woman, a resolute disciplinarian. Cleburne was a gem of a warrior.”

The “Stonewall of the West” was promoted to colonel in July 1861. His mentor, Gen. William J. Hardee, saw to it that Cleburne attained the rank of brigadier general on March 4, 1862, just in time to take part in the Battle of Shiloh. In the Confederate invasion of Kentucky in the summer of 1862, he was wounded at Richmond, Ky. He became a major general on December 12, 1862, quite an accomplishment for one who entered the war as a private barely a year and a half before.

But that was to be the end of his promotions, for in mid-December 1863, noting that the South was running short of much-needed manpower, Cleburne advocated what the North was already doing—using the Negro as a fighting man. He wrote a well-considered plan of freeing certain slaves and enlisting them in the Confederate service “to meet the growing manpower shortage in Southern arms.” Many of his superiors would not forward the document to President Davis, and it was left to Gen. W.H.T. Walker to do so. President Davis endorsed the document, but stated that the time was not ripe for its implementation. (About a month before Lee’s surrender, Davis resurrected the idea, but by then the war was lost.) In any event, friends and admirers of Cleburne believe that this advocacy “had much to do with his being denied promotion to lieutenant general.”

Beginning not long after Hood snapped shut his binoculars’ case and said that the Confederates would attack the Union forces at Franklin, the question arose as to why he did so in the face of 50 guns and a heavily entrenched Union force. The question extends to wondering why he didn’t wait for his artillery to arrive, and for Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee to come up with his divisions.

But Hood was impetuous. Moreover, it was growing late in the day and if he was going to fight that day it would have to be immediately. In addition, Hood remained angered at having missed Schofield at Spring Hill, and many are convinced that he meant to discipline his army by making the attack. Some are also convinced that he was mentally deranged at Franklin. Sick, weary and vexed, he was mentally unstable.

In any event, about 4 pm a signal flare was fired and the attack began. Looking toward the Union breastworks, General Cheatham’s corps was assigned the center of Hood’s attacking force, Cleburne’s division was to the right of the turnpike, and General Brown’s division was to the left. To Cheatham’s right was Gen. Alexander P. Stewart’s corps. Lee’s corps had not come up in time to join the battle line—only one of his divisions was at hand, and it was held in reserve. Regrettably, Forrest’s cavalry was divided and put on the two flanks of the Army of Tennessee. Even before the formal attack began, Forrest threw about three thousand men north of the Harpeth River and engaged Wilson’s force of five thousand. The ensuing cavalry battle lasted about an hour, until both sides ran out of ammunition. General Wilson later admitted that had Forrest’s “whole cavalry force advanced against him, it is possible that it would have succeeded in driving me back.”

Meanwhile on the south side of the river, 18,000 Confederates prepared for their assault. Then, bands playing, tattered colors flying, bayonets glistening, moving over more than two miles of open fields toward the Federal fortifications they marched in one of the grandest charges of the war, larger even than the far more famous Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg.

Startled rabbits fled before the advancing gray line, and coveys of quail took wing from the grass. The waiting Federal troops were for the moment spellbound with admiration as the Army of Tennessee moved resolutely forward. It was not to last. As Hood’s line came into range, the Federal artillery opened with canister and shrapnel. Where the shells burst Confederates dropped, but the regiments closed their ranks and marched on.

Cleburne and Brown’s divisions made first contact with Wagner’s men, who were out in front of the main Union line and late to fall back in good order. The Federals broke and ran helter-skelter to, then over, and then beyond, the principal breastworks. The Confederates followed on hard. Cleburne’s men made it to the Union parapet and leaped into the trenches, their bayonets jabbing. For a moment, the Union defenders were stunned and horrified to see the Confederates break their line. But Stewart’s corps to Cleburne’s right was slower getting up. Consequently, Cleburne’s men could not be supported and were soon in a merciless cross fire.

Cleburne, in the thick of the fight, had two horses shot from under him. He then moved forward on foot, waving his hat, encouraging his men forward. Recounted one of his brigade commanders, Gen. Daniel C. Govan: “I was the last one to receive any instruction from him, and as I saluted and bade him good-by, I remarked, ‘Well General, there will not be many of us that will get back to Arkansas,’ and Cleburne replied, ‘Well Govan, if we are to die, let us die like men.’” A short time later Cleburne was dead, his body found at dawn some yards from the Union breastworks, his boots stolen. One Federal soldier said: “I never saw men put in such terrible position as Cleburne’s division for a few minutes. The wonder is that any of them escaped death or capture.”

Brown’s division suffered a similar fate. They penetrated even farther into Federal lines than did Cleburne’s force. They were, in fact, closer to the bridge over the Harpeth than the flanks of Schofield’s army. But at this moment, a brigade of Wagner’s division that had retreated in good order through the middle of the Union breastworks before the fighting had begun, counterattacked at the Carter house. It was led by Col. Emerson Opdycke, a 34-year-old Ohioan with a reputation for competence and bravery. He fired all the rounds in his revolver, then broke it over the head of a Southerner and picked up a discharged rifle to use as a club. Brown’s men, winded from their running rout of Wagner’s other brigades held too long in front of the main defenses and their rush across the breastworks, could not widen their breach. The fighting raged with rifle butt and bayonet. Captain Tod Carter of Brown’s division and whose family home the Carter House was—indeed, his father and two sisters huddled in the basement throughout the battle—died nearly at his doorstep.

The fighting continued long into the growing darkness of that short afternoon of November 30, 1864. Some Union defenders insist that they counted 13 separate Confederate assaults. One Federal colonel wrote long afterward that: “It was impossible to exaggerate the fierce energy with which the Confederate soldiers that November afternoon threw themselves against the works, fighting with what seemed the very madness of despair. At some of the earthworks, the press of men was so great that the dead having no place to fall, remained in an upright position.”

The toll was especially ghastly on Southern generals. Five died outright: Cleburne, John Adams, Otho Strahl, States Rights Gist and Hiram Granbury. John Carter, mortally wounded, died within 10 days.

Adams, a native of Nashville, and a graduate of West Point in 1835, was at first seriously wounded in the arm. Refusing to leave the field, he led his men to the Union breastworks, which he attempted to jump with his horse. Both were riddled with bullets.

States Rights Gist of Brown’s division, a Harvard Law School graduate and son of a former South Carolina governor, was instantly killed while leading his men against the Union breastworks.

Otho French Strahl was an Ohio native but a Tennessee lawyer. Attached to Brown’s division, he was standing in a moat outside the Federal works handing up guns to his riflemen. His last words were, “Keep on firing.”

John Carpenter Carter, born in Waynesboro, Ga., was a practicing lawyer when the war began. Hiram Granbury, a native of Mississippi, was a lawyer and a judge in Texas before the war. A veteran since Fort Donelson, he died along with Cleburne within a short distance of the Federal fortifications.

Six other Southern generals were seriously wounded in the battle.

John Calvin Brown entered the war as a private and became a general officer in 1862. He was elected governor of Tennessee in 1870 and 1872.

Francis Marion Cockrell, a native of Missouri, after the war served as U.S. Senator for 30 years from his native state. He died in Washington, DC in 1915.

George Washington Gordon was captured by the Federals at Franklin. After the war he practiced law in Memphis and was the last Confederate general to sit in the U.S. House of Representatives. He died in Memphis in 1911.

Arthur Middleton Manigault, born in Charleston in 1826 became a rice planter. Later he served as adjutant general and inspector general of the South Carolina militia, dying in 1886 from complications of his old wound.

William Andrew Quarles was captured at Franklin and lived to 1893.

Thomas Moore Scott was a Louisiana farmer when the conflict began. He was severely wounded by the explosion of a shell and spent the remaining 12 years of his life on the Gulf Coast.

In addition to these general officers, the South lost 53 of about a hundred regimental commanders killed, wounded or captured at Franklin. Fourteen of 20 regimental commanders in Granbury’s brigade fell. Of the Federals, one general was wounded.

After the rage of the dying afternoon and evening, Schofield then did what he intended all along—abandon Franklin that night and retreat to Nashville, burning his bridges behind him.

If readers had had to rely on the battle communications of various commanders to their superiors, they would have received what the public wanted to hear, and not the true story of the senseless slaughter of a battle. Hood’s communication of December 3 to Confederate Secretary of War, James A. Seddon read:

“We attacked the enemy at Franklin and drove them from their center line of temporary works into the inner lines, which they evacuated during the night, leaving their dead and wounded in our possession and returned to Nashville. We captured shards of colors and about 1,000 prisoners. Our troops fought gallantly. We lament the loss of many gallant officers and many brave men.”

Two days later Hood further wrote Seddon that “our loss of officers in the battle of Franklin on the 30th was excessively large in proportion to the loss of our men. The medical director reports a very large proportion of slightly wounded men.”

The most ludicrous report was by the assistant adjutant general of the Army of Tennessee, on December 1, 1864:

“The commanding-general congratulates the army upon the success achieved yesterday over our enemy by their heroic and determined courage. The enemy has been sent in disordered confusion to Nashville. While we lament the fall of so many brave officers and brave men, we have shown to our countrymen that we can carry any position occupied by our enemy.”

Although Hood claimed Franklin as a victory, the holding of the ground that had cost him one third of his attacking force could hardly be considered an aid to his cause. Franklin was one of the bloodiest battles of the conflict (by comparative casualty rates) and has been called the “Gettysburg of the West.”

The Confederate casualties were reckoned at 6,252, of which 1,750 were killed. Even when Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee’s corps arrived, Hood had fewer than 18,000 effectives. The Confederates suffered more battle deaths than the Federals had at Fredericksburg, Chickamauga, Chancellorsville, Shiloh or Stone’s River. Hood’s force was practically destroyed as an offensive army.

Schofield’s losses were a third of Hood’s—2,326. Of these somewhat more than a thousand were captured, many in Wagner’s bumbled retreat, and 1,222 killed or wounded.

After his defeat at Franklin, Hood moved to the outskirts of Nashville and besieged Thomas who, with 60,000 men—including Schofield’s—had the larger army. It was stupid for Hood to advance to Nashville, but he believed his cohorts would dissolve from desertion if he did not put up a bold front. They awaited Thomas’s move. When the Union general was ready, he struck the feeble, undernourished and freezing Confederates on December 15. It was a complete Northern victory. Following this defeat, Hood turned the remnant of the Army of Tennessee over to Gen. Richard Taylor, son of Zachary Taylor. He never received such high command again. After the war he lived in New Orleans and died there in the yellow fever epidemic of 1879.

As the Army of Tennessee retreated from Nashville into Mississippi they sang the following song to the tune of their old favorite “The Yellow Rose Texas”:

So now I’m marching southward;

My heart is full of woe.

I’m going back to Georgia;

To see my Uncle Joe.

You may talk about your Beauregard;

And sing of General Lee.

But the gallant Hood of Texas;

Played hell in Tennessee.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments