By Christopher Miskimon

Adolf Hitler served in a Bavarian regiment on the Western Front during nearly all of World War I. He reached the rank of corporal and served mainly as a dispatch runner. The future Fuhrer received two injuries during his service, the first a wound during the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and the second a blinding by mustard gas in 1918. Most veterans of that conflict did not relish the memory of such things, but Hitler thought it was a wonderful experience, full of meaning and importance for him. Before the war he had been a drifter with no apparent future. His military service gave him the purpose he so desperately needed.

During World War I Hitler became fascinated by large, powerful weapons. The heavy caliber howitzers and mortars the German army used against the British and French gave him a sense of power and awe. When tanks appeared on the battlefield Germany struggled to respond to them, building only a few of their own and using captured examples when they could. Hitler saw in them power and brute force, preferring the heavier models which emphasized firepower and armor protection over the lighter, faster models. Over time, these beliefs solidified into dogma in his mind.

Decades later, on October 28, 1941, the former corporal ruled Germany, Austria and seven occupied nations in Europe. By that evening the Axis forces had just captured nearly 750,000 Soviet troops around Kyiv in Ukraine. Hitler sat in his headquarters in East Prussia eating his customary vegetarian meal with sparkling mineral water, confident that his genius and leadership was about to give Germany another great victory. He regaled his dinner companions with tales of his experiences, including Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, commander of German 4th Army.

Decades later, on October 28, 1941, the former corporal ruled Germany, Austria and seven occupied nations in Europe. By that evening the Axis forces had just captured nearly 750,000 Soviet troops around Kyiv in Ukraine. Hitler sat in his headquarters in East Prussia eating his customary vegetarian meal with sparkling mineral water, confident that his genius and leadership was about to give Germany another great victory. He regaled his dinner companions with tales of his experiences, including Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, commander of German 4th Army.

Along with his fellow general officers, Kluge had cause for worry, however. The forces in the east were winning great victories but their logistic support was precarious. With the Soviets destroying their rail lines, the Germans needed hundreds of thousands of trucks to keep their troops supplied. Germany could not make enough of its own trucks, so it used vehicles from captured territories, but this only increased the logistical strain by requiring a variety of spare parts and tires. German forces had to take frequent pauses for supplies to catch up.

Hitler did not care about the pace. “It’s the infantryman who sets the pace with his legs,” he told his guests. What German soldiers needed were more powerful tanks and artillery, not trucks. The German army did not need to move fast so much as it needed to hit hard. Hitler pushed this view on his soldiers; after all his genius had gotten them this far. Within a few months, however, the inexorable German advance was stopped, its troops freezing in the Russian winter, desperate for warm clothing and working trucks. Hitler still pushed his viewpoint; for the rest of the war Germany got bigger and more powerful tanks and wonder weapons, but never had enough trucks.

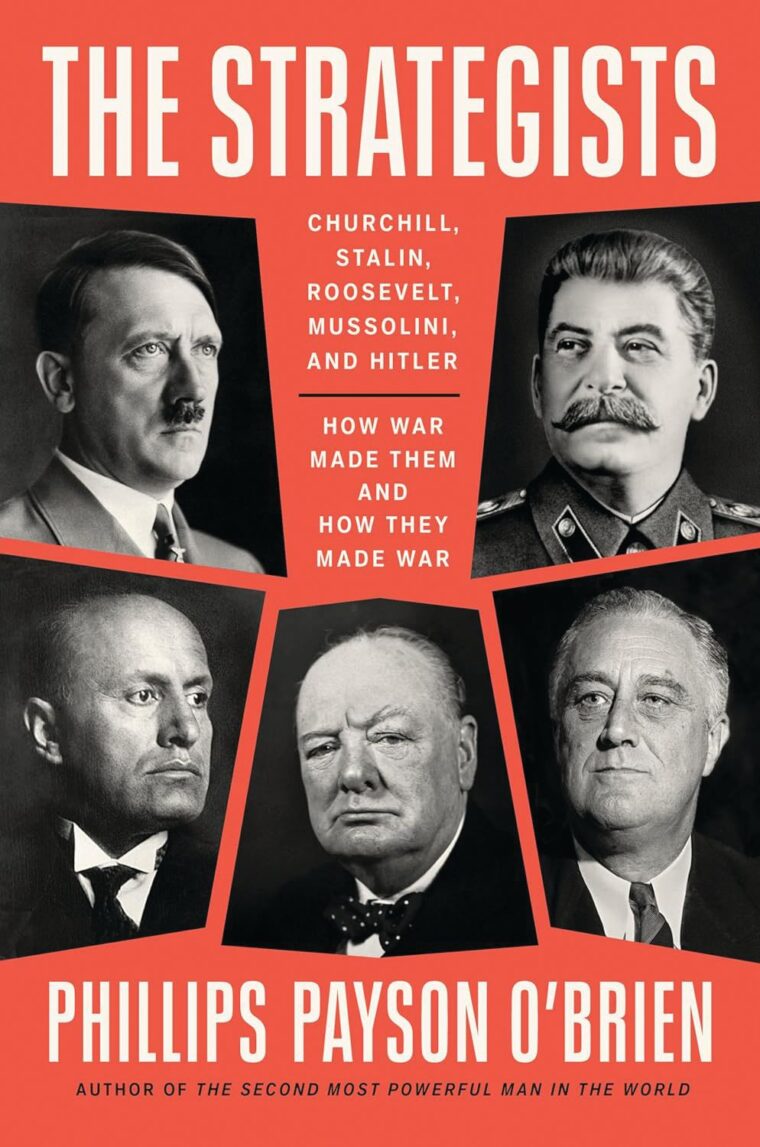

Hitler and the leaders of the other major western combatant nations all brought experiences of prior conflicts with them to their roles as commanders-in-chief. In Hitler’s case, it led to initial success but eventually to utter defeat. The stories of how their pasts informed their wartime actions is thoroughly relayed in The Strategists: Churchill, Stalin, Roosevelt, Mussolini and Hitler–How War Made Them and How They Made War (Phillips Payson O’Brien, Dutton Books, New York NY, 2024, 544 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $30, HC).

This book delves into the backgrounds of its subjects in great detail, but with a clear narrative that gives the reader a thorough understanding. The depth of research is apparent. The author further succeeds in winding together the disparate stories of these five men to show how their actions and interactions affected the course of the war. This book is readable and enjoyably so. The work deftly reveals how knowing what influences a leader’s mindset allows insight into how they will decide, act and react under the stress of war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments