By Jon Latimer

The art of sniping developed from the sharpshooting practiced during earlier conflicts. During the 19th century, the steadily improving technology of the rifle led to the use of sharpshooters during the American Civil War and the Boer War. However, it was during World War I that sniping progressed from simply a good marksman picking choice targets to the systematic use of selected men, trained and equipped with highly accurate rifles, telescopic sights, and high-grade ammunition, who engage high-value targets with single shots, usually at long range. But as is so often the case, immediately after World War I ended most of the protagonists discarded the skills and wisdom they had so painstakingly acquired, considering them no more than adjuncts of a type of warfare in the trenches that they dearly wished to forget. The British in particular, having taken a long time to recognize the potential for organized sniping, had been among its best practitioners by 1918 but were nevertheless swift to forget all they had learned. During the interwar period, little development took place. Although there was ad hoc sniping on both sides during the Spanish Civil War, it was Soviet advisers to the Republican side who chose to consider it further when they returned to the Soviet Union and introduced programs to the Red Army to augment existing civilian rifle shooting schemes. When World War II began, a new style of warfare was introduced; it was capable of swift and extensive movement and created very different battlefield conditions in a variety of theaters worldwide. In these conditions, the WWII sniper could adapt these previously invaluable skills to produce an effective weapon.

The German Army retained sniping as a specialization between the wars but showed little enthusiasm for its pursuit. In the opening campaigns in Poland and the West, the Germans moved so rapidly that there was no real opportunity for snipers to demonstrate their value. It was not until later in the campaign against the Soviet Union, after Soviet snipers had demonstrated their worth, that the German Army caught up. The British Army had been totally remiss in its attention to the skills it had done so much to develop previously. In 1942, sniping instructor Lt. Col. N.A.D. Armstrong commented on the attitude prevailing between the wars: “There appeared to be a tendency amongst Army musketry men to scorn the sniper—they held that sniping was only a ‘phenomenon’ of trench warfare and would be unlikely to occur again.”

Although training manuals still covered sniping, little was done at battalion level to maintain and encourage it until the retraining programs that followed the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk. However, British snipers were engaged in Norway and France during 1940.

WWII Sniper Edgar Rabbets: Second to None in Fieldcraft

Edgar Rabbets was a soldier in the 5th Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment, a Territorial Army unit. A country man from Boston in Lincolnshire, he was capable of catching a rabbit in his hands. When his unit was deployed to France he was appointed as a company sniper and given complete freedom of action to engage enemy snipers and high-value targets. By choice, he worked alone, although the common practice is for snipers to work in pairs.

During the retreat to Dunkirk, Rabbets was ordered forward to eliminate a German sniper operating in a Belgian village. According to Rabbets, “The sniper had got himself up in a roof and knocked a few slates away. He’d got a good field of fire if anyone walked into the square; he was roughly in the centre of one side of the square and his mate was in the corner. And they covered the whole square that way, the one effectively protecting the other.”

After the sniper had fired at a British officer entering the square, Rabbets found out “roughly where the flash had come from and went into a house opposite. The sniper was hanging out of the roof; I shot him from the bedroom window and he fell forward.” The observer fired blindly at Rabbets, thus revealing his own position. Rabbets was “firing deep from out of the bedroom window, and I wasn’t exposed to view. He assumed wrongly that I was a lot nearer to the bedroom window than I was. And he gave himself away, so that was his lot.”

Rabbets was an excellent marksman, capable of a first-round hit at 400 yards with the standard .303 Lee-Enfield rifle. But his outstanding fieldcraft, which may be generally defined as the use of camouflage and concealment, enabled him to close with the enemy and improve his chances of success. He also combined shooting with intelligence gathering, his freedom to roam giving him access to important information. He later wrote, “One day I went out and found a German military policeman standing at a crossroads; the only reason they stand at a crossroads is to direct a unit into a new position. I wanted to know what he was doing, so I crawled to within 150 yards range. He gave himself away by continually looking up the road to where he expected the unit to come from, and because there was only one direction to our lines, I knew roughly where they were going to. I shot him and then bundled him out of the way so that when the enemy got to the crossroads they wouldn’t know where they were going. Then I went back to my unit to give them this intelligence.”

Sniping began to take on greater significance after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. The Red Army had been practically the only army in the world to actively encourage sniping during the 1930s, and this had received added impetus from experience during the Spanish Civil War and the Russo-Finnish conflict. The Finns had seriously embarrassed the numerically superior Soviets, particularly showing great prowess with sniping. Many of them were hunters and naturally adept at the military application of their sport. Simo Häyhä was a farmer and hunter who went out to “hunt Russians.” He claimed more than 500 before being seriously wounded, and the hard lessons were not lost on the Soviets. They actively encouraged sniping and incorporated it into their infantry tactics. Their definition was broader than that of the West, tending to include general sharpshooting. They operated in pairs, and at low tactical levels, often being assigned to companies or even platoons, with junior officers experienced in handling them.

Russia’s Most Famous Sniper of the Second World War, Vasili Zaitsev, Claimed Over 100 Kills in Just 2 Months During the War

During the first two years of the war, the Soviets were largely on the defensive except for localized counterattacks. Snipers would be deployed forward of main defensive positions to engage reconnaissance patrols, artillery observation officers, and generally to delay enemy movement. Soviet snipers really came into their own during the battle for Stalingrad, where the ruins of the city provided excellent conditions for their operation. Snipers operated in front of their own lines, often for days at a time and completely isolated from their comrades despite being only a few hundred yards away from them. During daylight, they were often compelled to remain perfectly motionless. They suffered all the discomforts of the infantry soldier, often multiplied by the situations their specialized role required. Not only hungry and thirsty, they might be forced to urinate and defecate where they lay in order not to give away their positions.

During the Battle of Stalingrad, top Soviet snipers came to prominence. The most famous was WWII sniper Vasili Zaitsev, formerly a hunter in the Urals and a noted sniper before the battle, having claimed over 100 kills between August and October 1942. He founded a sniper school whose students received a two-day course before being sent into the ruined city to hunt Germans. Zaitsev became something of a celebrity, and his appearance in Soviet newspapers led the Germans to send for the chief instructor of the sniper school at Zossen near Berlin. A more personal contest could not occur in war. When some of the best Soviet snipers were killed by a rifle obviously fitted with a telescopic sight, Zaitsev knew he was up against a “Nazi super-sniper,” and set out to finish it one way or the other. He set off with his spotter, Nikolai Kulikov, and roamed the city for several days until he discovered a ruse that had obviously been set up to trap a Soviet sniper.

Zaitsev remembered, “Between the tank and the pillbox, on a stretch of level ground, lay a sheet of metal and a small pile of broken bricks. It had been lying there a long time and we had grown accustomed to it being there. I put myself in the enemy’s position and thought— where better for a sniper? One had only to make a firing slit in the sheet of metal and creep up to it during the night.”

Zaitsev was convinced, and when he carefully raised a false target, the German put a bullet clean through the middle. “Now came the question of luring even a part of his head into my sights … We worked by night and were in position by dawn. The sun rose. Kulikov took a blind shot; we had to rouse the sniper’s curiosity. We had decided to spend the morning waiting, as we might have been given away by the sun on our telescopic sights. After lunch, our rifles were in the shade and the sun was shining on the German’s position … Kulikov carefully—as only the most experienced can do— began to raise his helmet. The German fired. For a fraction of a second Kulikov rose and screamed. The German believed that he had finally gotten the Soviet sniper he had been hunting for four days and half raised his head from beneath the sheet of metal. That was what I had been banking on. I took careful aim. The German’s head fell back, and the telescopic sight of his rifle lay motionless, glittering in the sun….”

Soviet snipers were trained to operate in all phases of war. Deployed down to the lowest tactical level, they worked on the flanks of an advance to attack any targets that might slow it down. Such targets would include command elements and the crews of heavy weapons. Soviet snipers were expected to use their initiative in a way that was unusual for their rank- and-file comrades. As in most armies, the intelligence-gathering ability of snipers was utilized as a matter of course.

The prowess of Soviet snipers was something of an unpleasant surprise to the Germans, and despite being somewhat overblown by Soviet propaganda it undoubtedly made the Germans take notice and institute measures of their own. As the war went from bad to worse for the Germans, particularly on the Eastern Front, the cost-effectiveness of the sniper became increasingly apparent to German commanders at all levels. German sniping also benefited from a surprising patronage in the form of Heinrich Himmler, chief of the dreaded SS.

The Waffen-SS, the military element of Himmler’s organization, had taken a keen interest in sniping from the beginning of the war but was hampered by a shortage of suitable equipment. German sniper training was conducted at the highest level by 1943. Experienced snipers were withdrawn from the front to instruct sniper recruits, themselves selected from the best infantry marksmen. Particular emphasis was placed on camouflage and fieldcraft. Matthias Hetzenauer was Germany’s top wartime sniper with 345 confirmed kills. He was an exponent of the “one shot, one kill” philosophy. He recommended that snipers be chosen from “people born for individual fighting such as hunters, even forest rangers,” a practice followed by both the British and Americans. In contrast with the Soviets, German snipers usually worked in pairs but were organized at battalion level. As the prolonged war reduced the numbers of trained marksmen available, their orders might even come from division.

During the defensive battles later in the war, German snipers rather than machine guns were often used in delaying actions. Their ability to cause casualties to high-value targets, and their flexibility and mobility while remaining difficult targets themselves, made them ideal for these tasks. Captain C. Shore, author of the book With British Snipers to the Reich, cites an example of a few German paratroop snipers holding up an entire battalion of the 51st (Highland) Division in Sicily. Despite being subjected to artillery bombardment, these Germans maintained accurate fire at a range of 600 yards before withdrawing in good order. The toughness of the German infantrymen, combined with excellent training and initiative, led Allied soldiers to fear the German sniper.

After the disasters of 1940, British sniping was reinstituted in a haphazard fashion, with the quality of training varying in standard enormously. The warfare in the open desert of North Africa did not lend itself to sniper operations, but as soon as the closer country of Tunisia and Sicily was encountered, this changed. Here, accurate long-range shooting was at a premium, but it went against the grain of British practice that stressed closing with the enemy. One sniper officer came up with a solution: “We found an unsuspecting Boche about 600 yards away from us and could not get any closer to him. So we lined up three snipers together and got them to fire simultaneously, hoping that one of the bullets would hit. Our hopes were fulfilled!”

“During the Movement One Man was Shot by a Sniper Firing One Round. The Entire Squad Hit the Ground and They Were Picked Off, One by One, by the Same Sniper.”

Patience and careful observation were found to be the key ingredients for success, particularly where the enemy did not suspect the presence of snipers. Shore recounted one such action: “The forward platoon of the unit was in and around a cluster of smallish houses about 200 yards from the bank of the river. From the roof of one of these houses there was a good view of the top of the bank held by the Huns. Snipers watching the bank observed that the Germans changed their sentries every hour with monotonous regularity. At first the Hun was cautious and our snipers withstood the temptation to shoot, hoping that the targets would become even more favourable when the Jerries had lost some of their caution. Later in the day, the hoped for happened, and at 1200 hours, six of the enemy could be seen from the waist upwards. There were four of our snipers on duty and, having their set plan of execution ready, they each selected a Hun and fired. Three of the four Huns fell, and shortly afterwards, their bodies were dragged from the top of the bank by their comrades concealed below.”

The bocage country of Normandy provided excellent conditions for sniping, particularly for the defenders. A lone sniper or machine gun could dominate the close country. One American platoon leader described the difficulty with inexperienced troops, who tended to go to ground and stay there when under fire. “Once I ordered one squad to advance from one hedgerow to another. During the movement one man was shot by a sniper firing one round. The entire squad hit the ground and they were picked off, one by one, by the same sniper.”

The question of whether snipers should wear rank insignia was vexing for some. Shore’s commanding officer demanded that his officers cease the practice of wearing roll-neck jerseys that covered their collars and ties. “If we were to die, he said, we must die as officers!” It is important for officers to be instantly recognized by their men, but it is also clear that an identifiable officer was an inviting target for the sniper.

An aide to General Omar Bradley noted, “Brad says he will not take action against anyone that decides to treat a sniper a little more roughly than they are being treated at present.” If caught, a sniper could expect to suffer for his art. But the Germans did not have it all their own way during what became positional warfare for almost two months. Captain William Jalland of the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, found that his snipers regarded Normandy as ideal country, making good scores against careless German units.

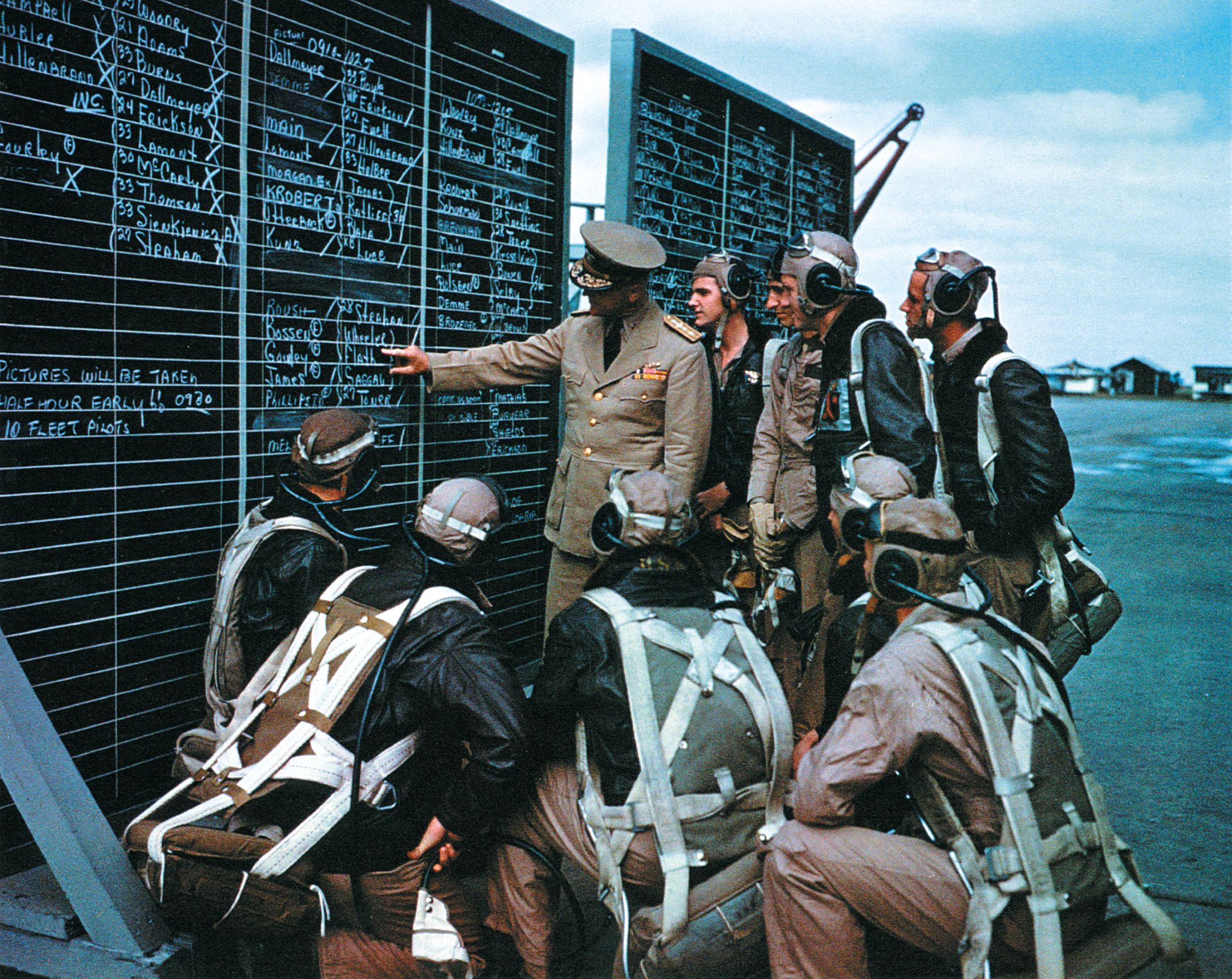

At the outbreak of the war, the U.S. Army was even less prepared for sniping than the British, and despite the obvious success of snipers against them in both the European and Pacific Theaters, senior American commanders never adopted a systematic program of sniper training. Although having access to many outstanding marksmen, this lack of commitment meant that results were haphazard indeed. Upon arrival in Tunisia, Colonel Sidney Hinds of the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment created a training course that lasted five weeks and graduated a number of snipers. Elsewhere, if commanders took no interest, nothing would be done. The chief weakness in U.S. training methods was the gap between marksmanship, which was of a very high standard, and fieldcraft, which tended to be less thorough. When some ad hoc schools were set up behind the lines, they tended to deal with handling the telescopic-sighted rifle rather than the tactical intricacies of the WWII sniper’s art.

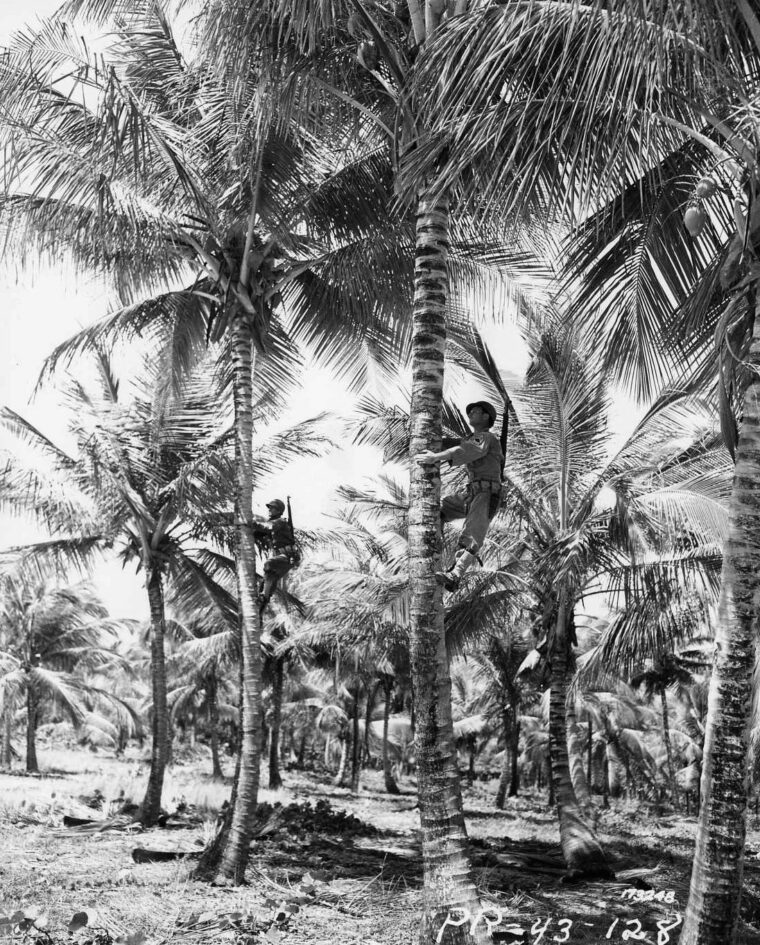

The Japanese were masters of camouflage, and since most of the fighting in Asia and the Pacific was at relatively short range, emphasis was placed on camouflage and fieldcraft. Each sniper was issued camouflage nets for helmet and body, although simpler methods were more common in the field. Tactics employed were broadly similar to those of Western armies, including the targeting of high-value installations, personnel, and equipment. One noticeable difference was the use of trees, even the rigging of small chairs among the branches and fronds.

Throughout the war, the Japanese sniper proved a constant trial to his enemies, from coral atolls in the Pacific Ocean to the forests of New Guinea.

The 1st Battalion, 163rd U.S. Infantry Regiment was badly troubled by snipers during one encounter. The divisional historian wrote, “From a tree almost anywhere around our oval perimeter, a Jap sharpshooter could choose a Yank target who had to leave his water-soaked hole. The range could be all of 200-400 yards. The keen-eyed sniper could steady his precision killing-tool on a branch and tighten the butt to his shoulder. He could take a clear sight picture and squeeze the trigger. All 1/Bn might hear is a Jap .25-caliber (6.5mm) cartridge crack, like a Fourth of July cap cracked on a stone. Then a Yank cowering in a hole might hear the prolonged dying groan of a man in his next squad. Or long after a deadly silence, he might find his buddy a pale corpse with a deceptively small hole in his forehead.”

The elimination of snipers was difficult business, but the Americans were nothing if not thorough. Two-man countersniper teams manned the forward defenses while other teams set off to climb the jungle trees Tarzan fashion and guide others along the ground. Through careful coordination of these elements, the snipers were eradicated one at a time. Rounds from 37mm antitank guns firing canister were found to be effective, blasting whole areas where snipers were suspected. British and Commonwealth troops used similar tactics, and once the Japanese sniper was seen for what he was, certainly not a superman, then the battle against him was largely won. As the war progressed, the quality of the Japanese sniper deteriorated, and the British began to have some notable sniping success of their own. One report describes the combined sniper strength of two brigades (48 snipers) having killed 296 Japanese in a two-week period, for the loss of two men killed and one wounded in the finger.

Australians made excellent snipers, the best being those who had been kangaroo hunters. A ’roo hunter must be a superb shot since a clean kill preserves the pelt and will not disturb the other ’roos. Most of them were already experienced with the heavy .303 Lee-Enfield rifle. One such hunter turned sniper accounted for 47 Japanese on Timor but only claimed 25, on the basis that “you can’t count a ’roo unless you saw him drop and know exactly where to skin him.” The Australians fought a guerrilla campaign against the Japanese on Timor, killing some 1,500 for the loss of 40 and forcing the Japanese to divert large reinforcements.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments