By Patrick J. Chaisson

Colonel Ed Raff kept glancing at his wristwatch while trying to control the growing sense of dread inside him. At any moment, he knew, dozens of American cargo gliders were due to arrive overhead.

Yet well-armed enemy infantrymen and machine gunners dominated the gliders’ designated landing fields. Unless those soldiers were defeated, chaos would prevail. Keeping one eye to the skies and another on his watch, Raff worked furiously to organize an all-out assault on the foe’s stronghold.

At 2053 hours, the far-off throbbing sound of aircraft engines told him he had run out of time. Minutes later they appeared: 75 twin-motored Douglas C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft, each towing a giant Horsa or Waco glider. The C-47s’ flame dampeners glowed white-hot against the gathering dusk as they approached their release point.

The low-flying air armada was too big a target to miss. As Colonel Raff looked on helplessly, a sheet of machine-gun fire erupted skyward from the enemy positions. Mortally wounded tug planes and gliders alike began spiraling down to crash land among the hedgerows. Those men able to crawl out of their wrecked aircraft stumbled dazedly around the battlefield, often falling prey to a sniper’s bullet.

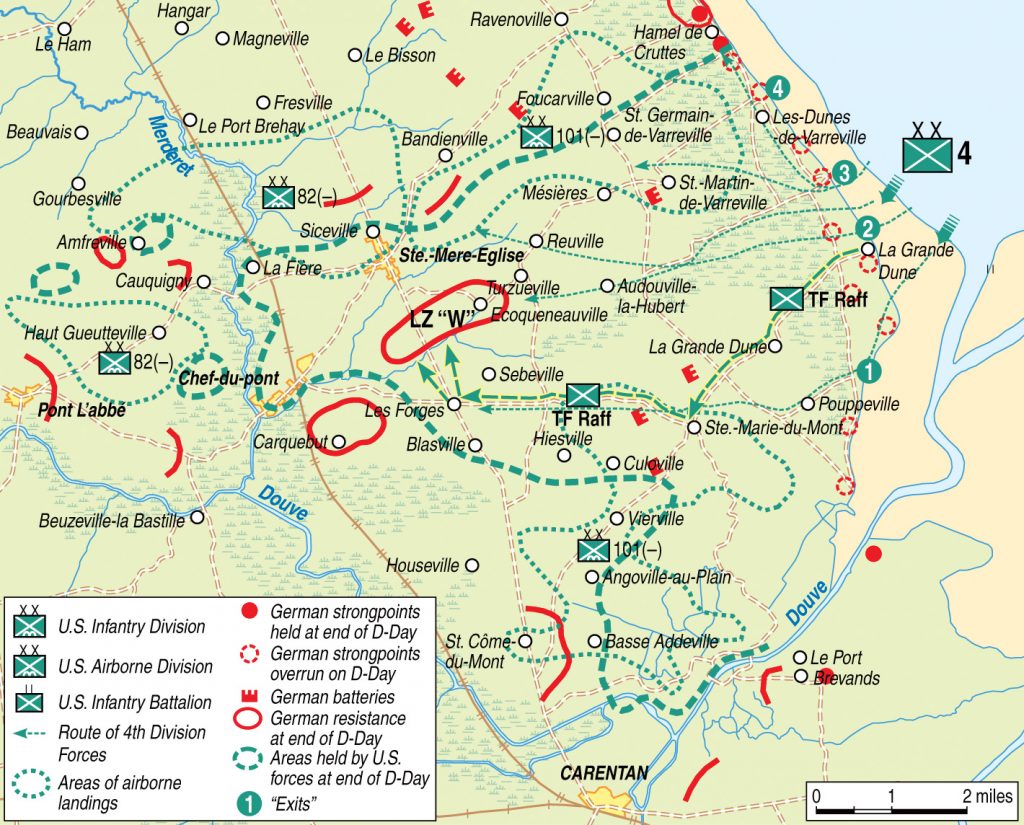

This incident, which took place near the road junction of Les Forges, France, was only one of many small-unit actions to occur on D-Day, June 6, 1944. It was a desperate attempt to link up the massive U.S. force landing across Utah Beach with some 6,000 paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division, who’d jumped into battle earlier that morning near the French village of Ste. Mère-Église.

Located near the center of Normandy’s Cotentin Peninsula, Ste. Mère-Église sat astride the main highway from Carentan to Cherbourg. The 82nd Airborne’s D-Day objective was to take and hold this key crossroads, as well as a pair of bridges spanning the Merderet River west of town, in order to prevent German defenders from staging a counterattack against Utah Beach.

It was a mission that would sorely test the “All-American” Division and its aggressive commander, Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway. Only his 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) had combat experience; the attached 507th and 508th PIRs were well-trained but new to battle. Furthermore, Ridgway could not rely on personally greeting his veteran 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR) until the morning of June 7 (D+1) owing to a shortage of transport planes.

Apart from two 75mm howitzers parachuted in before dawn on D-Day, most of the 82nd Airborne Division’s heavy weapons would land by glider. The 319th (75mm) and 320th (105mm) Glider Field Artillery Battalions (GFABs) were to come in that evening, along with several 6-pounder (57mm) anti-tank guns belonging to the 80th Airborne Anti-Aircraft Battalion (AABN).

Ridgway demanded all these guns, especially the 80th AABN’s 6-pounders, arrive safely and on target. Just before D-Day, however, Army intelligence identified a dangerous new threat moving into his area of operation: The German 91st Air Landing Division, equipped with tanks and specially trained to defeat paratroopers.

Initially, the “All-Americans” would have to fight these powerful adversaries with a minimum of organic artillery support. While U.S. troops moving inland from Utah were supposed to make contact with the 82nd Airborne by dusk on June 6, a host of factors—from bad weather to unexpectedly heavy resistance on the beachhead—could scuttle that plan. General Ridgway needed to find a way of evening the odds.

His solution was to form an armored “breakthrough force” that would land with the first waves on Utah and then advance on Ste. Mère-Église to help defend against enemy counterattacks. Ridgway further insisted that a paratrooper lead this mechanized team. Only a fellow airborne officer, he figured, would understand what was at stake and act with the requisite urgency.

In mid-May, a seemingly ideal candidate for the job reported to 82nd Airborne Division HQ. Colonel Edson D. Raff, a planner on the First U.S. Army staff, had for months been pestering his boss for a combat assignment. That officer, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, finally granted Raff’s requests by transferring him into Ridgway’s command in May 1944.

Raff, 36, was already somewhat of a celebrity within the American airborne community. His outfit, the 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR, became the first U.S. Army paratroopers to see action in World War II when they parachuted into North Africa as part of Operation Torch in November 1942. He later wrote a book, We Jumped to Fight, detailing his experiences there.

Ed Raff made it very clear to all who would listen that he wanted to command a parachute infantry regiment in battle. Yet his ambitious nature, abrasive personality, and dim regard for most senior officers created friction nearly everywhere he served. As CO of the 2/509 PIR, Raff had earned the unflattering nickname “Little Caesar” due to his imperious leadership style and somewhat-stocky physique. While personally courageous, he showed no patience for weakness or mediocrity.

Neither Maj. Gen. Matt Ridgway nor his deputy commander, Brig. Gen. Jim Gavin, saw much room for Edson Raff in the “All-American” Division. Their first encounter with the newly assigned colonel did not go well. Curtly, Ridgway informed Raff that his infantry regiments already had competent commanders in place, and he was not about to change things this close to the invasion.

Instead, Raff was to come ashore on Utah Beach together with a company of medium tanks, some recon vehicles, and infantry. He was then to lead them eight miles through the lines to Ste. Mère-Église, overcoming all obstacles in his path. The 82nd Airborne Division counted on these reinforcements to arrive before German armor could move in and crush its lightly-armed paratroopers.

While Raff surely wished he had been allowed to make the jump into Normandy, he did perceive a certain opportunity in this alternative mission. A “spare colonel,” Raff would be immediately available to replace any of Ridgway’s airborne regimental commanders who were killed, wounded, or declared missing in action during the coming campaign. He simply had to accomplish his assignment and stay alive.

Raff also learned his command now belonged to “Howell Force,” the 82nd Airborne’s seaborne echelon. There weren’t enough parachutes or gliders to transport the entire division by air; its quartermasters, MPs, and maintenance personnel would come ashore by landing craft and join up later. Brig. Gen. George P. Howell, another long-serving airborne officer, ran this operation from his temporary headquarters in the port city of Dartmouth.

There, Raff met the officers who were to work for him on D-Day. Captain James A. Crawford led Co. C, 746th Tank Battalion and its 18 M4 Sherman medium tanks. In addition, 2nd Lt. Gerald H. Penley had two M8 armored cars and four jeeps in his Third Platoon, B Troop, 4th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. Finally, there were 90 infantrymen on hand from Company F, 2nd Battalion, 401st GIR. This outfit, previously part of the 101st Airborne, had been separated upon its arrival in England to reinforce both the “Screaming Eagle” and “All-American” Divisions. For Normandy, 2/401 GIR joined the 82nd’s 325th Glider Infantry Regiment as its unofficial third battalion.

While in Dartmouth, Raff also met an unusual man who had been named as his second-in-command. Major Ralph M. Ingersoll, a New York City magazine publisher in civilian life, served on General Bradley’s special staff until he, too, obtained a transfer to combat duty. They made for an odd pair: the thickset, career paratrooper and his lanky citizen-soldier executive officer, yet both men were equally eager to get on with their mission.

On June 4, with all vehicles loaded aboard, the small flotilla carrying TF Raff left to war, departed for France. The tanks, along with Raff, Ingersoll, and their glidermen, sailed in British-crewed Landing Craft, Tanks (LCT) while Lieutenant Penley’s recon troops came across in smaller Landing Craft, Mediums (LCM).

The invasion fleet maintained strict radio listening silence throughout its cross-Channel journey. As dawn broke on D-Day there was no news of the 82nd Airborne’s night drop, nor whether its G.I.s had accomplished any of their assigned tasks. In truth, Ridgway’s division was fighting for its life among the fields and marshes of Normandy.

Starting shortly after midnight on June 6, approximately 6,000 “All-American” paratroopers jumped into German-occupied France. A combination of low clouds, heavy antiaircraft fire, and inexperienced Troop Carrier pilots severely unhinged the drop. Only one regiment, the 505th PIR, landed anywhere near its objective; the rest of Ridgway’s men and matériel were scattered all across the Cotentin Peninsula.

Another unpleasant surprise greeted those parachutists floating down over Normandy: Much of the region had been deliberately flooded by German forces. Many jumpers drowned before they could even see action, while dozens of essential equipment bundles simply disappeared underneath the murky swamp water. The glider carrying General Ridgway’s powerful liaison radio plowed into the Merderet River, preventing him from communicating with anyone outside his division’s perimeter.

Some “All-Americans,” however, were able to carry out their orders. In particular, 1st Battalion, 505th PIR succeeded in capturing a key bridge at La Fiere, while another hundred or so 507th PIR paratroops grabbed the span at Chef-Du-Pont. After clearing Ste. Mère-Église, soldiers raised a small U.S. flag over the town, the first French village to be liberated on D-Day.

Ridgway and Gavin constantly roamed the battlefield, trying to create order from the tactical nightmare in which they found themselves. They eventually formed a triangle-shaped perimeter with one point at Ste. Mère-Église to the east, another at La Fiere two miles due west, and the third at Chef-Du-Pont in the south. Unit leaders next set up blocking positions to cover key avenues of approach, while a small reserve of mis-dropped 507th and 508th men assembled just outside of town.

The foe reacted swiftly to this airborne incursion. At 1300 hours, infantrymen from the 91st Air Landing Division’s 1058th Regiment collided with a platoon posted at the hamlet of Neuville-au-Plain two miles north of Ste. Mère-Église. Three hours later, another probe by the 91st’s 1057th Regiment headed toward the bridge at La Fiere. These German counterthrusts were well-supported by armored vehicles, mortars, and field artillery.

Thanks to the skill and bravery of his paratroopers, Ridgway managed to blunt both assaults. He experienced less success to the south, though. There, an understrength rifle company from 3rd Battalion, 505th PIR spent most of June 6 trying and failing to seize Hill 20, a long ridgeline located about halfway between Ste. Mère-Église and the road junction at Les Forges.

Holding Hill 20 was a battalion of Ostruppen, Red Army prisoners of war who chose service with the Wehrmacht over slow death in a Nazi prison camp. Ostbataillon 795, commanded by a Captain Stiller (some sources cite his name as Ziller), numbered about 925 men: 90 or so German officers and NCOs, the rest ethnic Georgians from the Caucasus region of Soviet Russia. Although deemed “unreliable” by higher headquarters, the 795th was well-armed with .45-machine guns and a number of anti-tank cannon. Critically, Stiller’s troops could cover with fire a U-shaped valley labeled Landing Zone “W” (LZ W)—site of a major glider-resupply mission set to commence at 2100 hours.

General Ridgway needed to clear Hill 20 but lacked the means to do so. Worse, because of his ruined radios, he could not warn the pilots approaching LZ W to land someplace safer. As evening drew on, he began to worry if the assault on Utah Beach had even taken place. Raff should have reached Ste. Mère-Église by now, yet there was still no sign of him or the main seaborne force, Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton’s 4th “Ivy” Infantry Division. Had the 82nd Airborne Division been left to die in Normandy?

Unbeknownst to the paratroopers holding Ste. Mère-Église, a massive amphibious operation was even then putting thousands of American soldiers onto Utah Beach. It started off poorly; navigation errors and an unexpectedly strong tidal current caused the invasion’s first waves to land 2,000 yards south of their objectives. Famously, the 4th Infantry Division’s onshore commander, Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., remedied this crisis by declaring, “We’ll start the war from right here.” He directed his men to turn north and take their primary objectives—several important causeways leading inland–on the fly.

The first element of TF Raff to hit Utah Beach was Lieutenant Penley’s cavalry platoon, which touched down at 0925 hours. Despite all efforts made to waterproof them, several vehicles “drowned out” while driving off their LCMs. It took 45 hectic minutes to get those machines restarted, during which time the unit came under heavy artillery fire. Penley lost two jeeps and four troopers wounded before he could move his men to a sheltered assembly area where they would wait for the main body to show up.

At 1400 hours, the landing craft transporting Raff’s tanks and glidermen arrived. Major Ingersoll remembered how his LCT’s skipper “rammed the boat home” right up on shore so “our big tanks hardly splashed themselves from the ramp to the dry beach.” Each M4 then “waddled across [the sand], up-ended over the dunes, and was out of sight.” Tank crews next got to work stripping off their vehicles’ waterproofing sealant, as well as unneeded deep-water wading trunks, in preparation for combat.

The last of Captain Crawford’s Shermans to come ashore towing behind it a command jeep, specially fitted with an armored windshield and pedestal-mounted .50-caliber machine gun. Raff and Ingersoll, together with their driver and gunner, would make the journey to Ste. Mère-Église in this small, open-topped vehicle.

At 1730 hours, Colonel Raff told everyone to mount up. Company F’s troops, including Pfc. Lucius P. Young, were ordered to “ride at the back of the tanks, four men on the back of each tank,” as he later recalled. With Lieutenant Penley’s armored cars leading, the column maneuvered its way through an incredibly congested beachhead and began heading inland along the two-mile-long causeway known as Exit 2.

In a matter of minutes, the mechanized breakthrough force reached a small village named Ste. Marie-du-Mont, just five road miles from its destination. Encountering “absolutely no opposition” thus far, Raff said the ride reminded him of a Sunday drive in the country. Now headed west toward Les Forges, he learned why things had been going so well.

Up ahead, American infantrymen could be seen cautiously making their way through pastureland on either side of the roadway. These soldiers belonged to Lt. Col. Erasmus H. Strickland’s 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, one of the first “Ivy” Division outfits to storm across Utah that morning. Advancing steadily all day, Strickland’s battalion had by 1900 hours cleared a swath of terrain all the way up from the beachhead to Les Forges—its D-Day objective.

The G.I.s digging in there warned Colonel Raff of an enemy strongpoint along a ridgeline about 1,000 yards to the north that had already fired on their lead platoons. A quick check of his map indicated this was Hill 20, the last danger area before Ste. Mère-Église. Between lay a swampy, tree-covered valley: LZ W.

Raff identified the problem immediately. “It was urgent that the valley be cleared for the glider elements from England,” he recalled. “I ordered my tanks to attack.”

Before his Shermans could advance, however, Raff needed to find out what was in front of them. Summoning Penley, he told the cavalryman to “take your scout car up the road and see what you can see.” An M4 tank would follow closely behind to provide covering fire.

The small reconnaissance team cautiously edged forward perhaps 300 yards. Then from Hill 20 a high-velocity cannon barked, its shell ripping completely through the thin-skinned armored car. This lucky projectile kept going, somehow tearing a track off the accompanying Sherman. Its crewmen, along with Penley’s scouts, all piled out of their stricken vehicles and headed for safety.

With his foe’s position now pinpointed, Col. Raff quickly devised an attack plan. First, he instructed Major Ingersoll to locate the 8th Infantry Regiment’s Cannon Company in position some distance behind them. That battery, equipped with six 105mm howitzers, would suppress the gunners occupying Hill 20 with high-explosive shellfire.

His next orders went to Captain Crawford, the tank company commander. “Deploy your infantry and armor on either side of the road,” Raff said, “and take that hill.” It was now 1930 hours.

Rifleman Lucius Young witnessed what happened next: “I, along with three other men, went out to the hedgerow nearest to the field on guard duty. One tank went up the road next to us and was hit by an 88 [sic]. Another tank tried to make it and it too was hit by an 88. The third tank went around through the field, but I understood an 88 hit it as well.”

Young, like most G.I.s, believed the enemy weapons on Hill 20 were all 88mm dual-purpose artillery pieces. Penley later identified them as captured Soviet 76mm anti-tank guns.

In a matter of minutes, Company C lost yet two more M4s to the Georgians’ deadly fire. Casualties were heavy; 2nd Lt. Joe M. Mercer was mortally wounded. Yet Raff’s tanks had already advanced halfway across the valley; one more push, he figured, might just do it.

This noisy encounter attracted the attention of the 8th Infantry commander, Colonel James A. Van Fleet, who came forward to see what was going on. Raff met Van Fleet with an appeal for help: “I pleaded with him to make an attack to drive out the enemy forces across the way,” the paratrooper said. “He demurred, saying he had reached his forward line for the day.”

Captain Crawford radioed in some more bad news: his Shermans were bogging down in the marshy valley, while Cannon Company had to cease fire due to low ammunition supplies. Raff realized he did not possess the combat power necessary to capture Hill 20; that job required the entire 3,000-man 8th Infantry. Unfortunately, its commanding officer stood before him, not sharing his sense of urgency.

Meanwhile, at an altitude of between 750 to 1,500 feet, 75 U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) tug-glider combinations made landfall directly over Utah Beach. This was Echelon One of Mission Elmira, a massive D-Day glider assault carrying into France two entire field-artillery battalions, a battery of anti-tank guns, medical personnel, tactical vehicles, and trailers full of much-needed munitions. Unable to communicate with General Ridgway’s command post, Elmira’s transport pilots remained oblivious to conditions on the around Hill 20.

Raff described their arrival. “To my horror, at 2100 [hours] the glider lift came in low over the valley. Like watching a movie in which the full plot was known, I realized the smoking knocked out tanks were appearing as LZ markers in the evening light to the pilots in the troop carriers, so unerringly did they release their gliders over that valley.”

Every member of Ostbataillon 795 then pointed his weapon skyward. “The whole hilltop began to crackle with small-arms fire going up towards the planes,” recalled Major Ingersoll. “One of the [C-47] transports suddenly began smoking. It roared over our heads and thundered into a field just behind us.”

The airmen piloting their unpowered Horsas and Wacos had no choice but to attempt a landing. “Gliders were crashing into hedgerows all around the valley,” Colonel Raff recollected. “One or two … even landed on the hill occupied by the enemy.” Ralph Ingersoll added, “It was too small a landing zone for so many gliders.”

Indeed, Allied air planners had made a major miscalculation when they selected this valley as Mission Elmira’s landing zone: The official Troop Carrier history contains a vivid description of LZ W: “Not only were there ‘postage stamp’ fields 200 yards long, bordered by 50-foot trees, but also some of the designated fields turned out to be flooded and others were studded with poles more than 5 inches thick and 10 feet or more in height. Trip-wires for mines had been attached to many of the poles but fortunately, the mines themselves had not been installed.”

Unable to reach a large field, one Horsa pilot “picked a small one, lowered his flaps, and landed at about 70 miles an hour,” recounted USAAF historian John C. Warren. “The glider bounced twice and when about 10 feet off the ground on its second bounce crashed through a row of trees which stripped it of its wings and landing gear. The craft scraped to a stop 10 yards behind Raff’s forward positions.”

Flight Officer Ben O. Ward of the 81st Troop Carrier Squadron tried to bring his glider down safely, unaware that its brakes had been damaged by enemy fire. “Just ride it out,” Ward told himself as the Horsa smashed sideways into a hedgerow. “The sound of shattered plywood and crunching plexiglass filled my ears … then silence. I was dazed by the impact … and staggered to my feet, wondering if I was still in one piece.”

The Waco carrying Pfc. Menno N. Christner of Battery C, 80th AABN, hit a tree and disintegrated. Christner was thrown clear but discovered he had broken three ribs on impact. After helping to rescue his pilot and co-pilot from the wreckage, the young gliderman attempted to orient himself. “I heard a lot of gunfire all around and didn’t know which way to go.”

Forming “glider rescue teams,” Raff’s soldiers attempted to assist those who were either trapped inside wrecked aircraft or, like Christner, found wandering around no-man’s land. The most grievously injured gliderman were evacuated back to 4th Division aid stations. Meanwhile, Major Ingersoll attempted to organize all able-bodied pilots and glidermen into ad hoc infantry. These reinforcements, Ingersoll hoped, could join TF Raff in a final, desperate attack on Hill 20.

Yet those who survived the landings were, by and large, so stunned by their cruel introduction to combat that Raff could expect nothing further from them that evening. Besides, he knew a second wave of cargo gliders was set to arrive right at sunset.

Again, Colonel Raff could only look on in frustration as another 100 glider combinations passed low overhead. The Georgians on Hill 20 unleashed a fresh torrent of fire against them, and once more young American aviators pushed their flimsy canvas and plywood aircraft down for a landing among the hedgerows in semidarkness.

The overloaded Horsa transporting Pfc. Wilmer Ranninger of Battery B, 319th GFAB, struck a tree on its descent. “There was a terrible and loud sound after we hit the tree,” he recalled, “and the glider itself began to break up even before we touched the ground. I was thrown toward the floor of the glider, and my head and shoulder actually fell through an opening in the floor. As the glider skidded through the ground, my head and shoulder were repeatedly bounced on the hard, rocky ground.”

First Lieutenant Edgar A. Schroeder, with the 320th GFAB’s Battery B, also experienced a violent crash landing. “We banged down in the middle of the field and bounced into the hedgerow,” he said. “I thought I had a broken leg, but after shoving aside a ton of debris … I managed to crawl through what was left of the nose section and got to my feet.” Schroeder was fortunate in that he sustained “only bruises, contusions, and a slight concussion” during his harrowing entry into France.

Wacos and Horsas dove earthward in all directions. Paratrooper Sergeant Otis L. Sampson went to the aid of one aircraft that had crashed within the 82nd Airborne’s perimeter. “As I came up, a hole started to appear on the right side of the glider. The men were kicking out an exit. Like bees out of a hive, they came out of that hole, jumped on the ground, ran for the trees, and disappeared. I tried to tell them they were in friendly country, but they passed me as if I wasn’t even there.”

And not every glider landed in U.S.-held territory. Wehrmacht Sergeant Rudi Escher of the 91st Air Landing Division’s 1058th Regiment remembered encountering a shattered Horsa that night. “We opened a side door in the glider,” he wrote, “and two Americans were sitting there, absolutely still, their weapons at the ready. They must have been absolutely petrified.” Escher’s group took the G.I.s prisoner before destroying their plane “with firebombs and grenades.”

Casualties included 15 glider pilots killed, 17 wounded, and four missing. The 82nd Airborne’s glidermen suffered 33 killed and 124 wounded, although many soldiers initially listed as missing eventually found their way into American lines. Yet Mission Elmira successfully delivered to Ridgway’s division 15 of 24 howitzers, 42 of 59 jeeps, 28 of 39 trailers, and 33 tons of ammunition. All eight anti-tank guns from Battery C, 80th AABN, came in unharmed, one landing so close to the Chef-Du-Pont bridge that it was immediately offloaded and put into action against attacking German armor.

The “flying coffins” that brought these men and equipment into Normandy did not fare so well. Fewer than half of the 36 Wacos used in Mission Elmira landed intact, with eight listed as total losses. Of 139 Horsas employed that evening, 56 were entirely destroyed either on landing or by enemy fire. Only 23 survived in undamaged condition.

Raff himself attested to their fragile construction. “The British gliders made of wood completely disintegrated in the crashes,” he remarked to an Army historian some weeks later. After Normandy, U.S. airborne forces would never again use the Horsa in battle.

As a brief June night finally fell, it seemed pointless to continue the advance on Ste. Mère-Église. While his troops rested, Raff went back to confer with the “Ivy” Division’s commanding general. Finding Maj. Gen. Barton at his Utah Beach HQ, Raff convinced him to commit the 8th Infantry Regiment to an early morning assault on Hill 20. Captain Crawford’s tankers would provide armored support.

While it took some time for Colonel Van Fleet’s inexperienced riflemen to get organized, by noon on June 7 they had wrested that key hilltop from Ostbataillon 795. The 8th Infantry’s hasty attack netted over 175 prisoners of war, but—more importantly—finally established a firm connection between the “All-American” Division and the Allied units advancing inland from Utah.

In the meantime, Lieutenant Penley’s recon platoon headed west toward Chef-Du-Pont and Ste. Mère-Église. Following directly behind them in an unarmored jeep was Brig. Gen. Ted Roosevelt. The plucky little general met an anxious Matt Ridgway with his characteristic grin and a question: “Which way to the picnic?” This joke reassured everyone within earshot that all would soon be well.

Raff and his Sherman tanks rolled into town around 1200 hours. The infantrymen of Company F immediately rejoined their parent battalion, which had arrived by glider earlier that morning, while Crawford’s tanks moved forward to help defeat a series of enemy counterattacks. The irrepressible Major Ingersoll kept busy all day escorting resupply convoys from Utah Beach to Ste. Mère-Église.

With his mission now complete, Colonel Raff no longer had a job. As the 82nd Airborne’s chief of staff had been badly injured in a glider crash, Maj. Gen. Ridgway temporarily appointed his “extra colonel” to this post. One week later, Raff took over the 507th PIR after it was learned that outfit’s CO, Colonel George V. Millett, had been captured.

Ed Raff served creditably with both the 82nd and 17th Airborne Divisions during World War II, making another combat jump as part of Operation Varsity in March of 1945. Staying with the postwar Army, he became an early proponent of unconventional warfare. Historians often credit him for introducing the green beret as a symbol of modern Special Forces soldiers.

A sadder fate awaited many of the G.I.s who fought under Raff’s command on D-Day. On June 9, Pfc. Lucius Young suffered a serious bullet wound to his neck while advancing across the La Fiere causeway. That bloody attack also took the life of Company C’s commander, Captain James Crawford. In September, cavalryman Lieutenant Gerald Penley was killed in action as his unit entered Belgium.

The region around Ste. Mère-Église bore battle scars long after the war had moved on. An American staff officer noted in mid-June that “all along the roads in this area were smashed gliders, some stripped of their clothing [fabric], others completely burned out, hung out and draped against trees and hedges. How the men came out alive to fight as they have fought is something of a miracle.”

At great cost, airborne forces in Normandy kept Utah Beach secure from enemy counterattack. These paratroops and glidermen next helped seal off the Cotentin Peninsula, enabling other First U.S. Army formations to seize the city of Cherbourg and its vital deepwater port. With Cherbourg secure, the Allies then prepared to enter a new and deadly phase of combat–breakout.

Author Patrick Chaisson is a retired US Army officer and historian who writes frequently for WWII History from his home in Scotia, New York.