By Charles W. Sasser

World War II, the deadliest military conflict in history, claimed the lives of nearly four percent of the Earth’s 1940 census. Hitler’s Holocaust against the Jews alone destroyed over six million of the approximately nine million Jews in Europe in 1933. Upon Hitler is assigned the evil that resulted in what scholar Steven T. Katz described as an effort to “annihilate physically every man, woman, and child belonging to a specific people.”

Hitler’s ambition to develop a “master race” by proper breeding and elimination of the “unfit” did not rise out of a vacuum. The philosophy he embraced around eugenics and euthanasia had proliferated in the Western World for a half century, most notably in the nation that, ironically, would be the most instrumental in defeating him in World War II. Hitler himself attributed his inspiration to breed a super race to the United States and those individuals and groups who strived to eliminate flaws and imperfections in the human race.

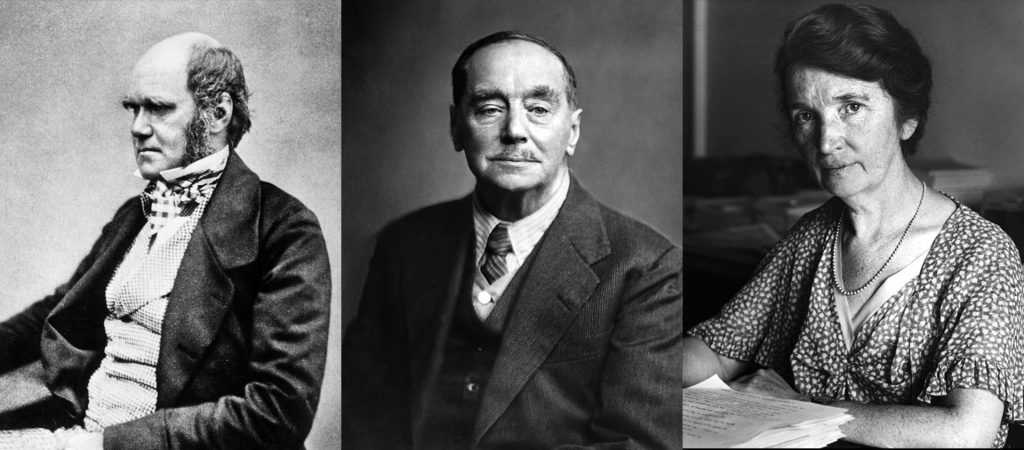

Eugenics and euthanasia, the science of properly breeding the human race and the destruction of the defective, claim deep roots in world history. Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle endorsed eliminating “weak children” and allowing only men and women with superior characteristics to mate and bear offspring. In the 19th century Charles Darwin spread the philosophy into the modern Western World.

To him, natural selection for the betterment of the species was perfectly reasonable. If unfit livestock ought to be eliminated for the health of the herd and not allowed to reproduce, he argued, why should we encourage the breeding of unfit humans?

“With savages,” he further elaborated in On the Origins of the Species and the Descent of Man, “the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated…. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination. We build asylums for the imbeciles, the maimed, and the sick; we institute poor laws; and our medical men exert the utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment. [If we] do not prevent the reckless, the vicious, and otherwise inferior members of society from increasing at a quicker rate than the better class of men, the nation will retrograde, as has too often occurred in the history of the world.”

In a 1904 edition of The American Journal of Sociology, author H.G. Wells offered his recommendation that society “rout out and eliminate urban rookeries and all places where the base can drift to multiply … so that childbearing shall cease to be a hopeful speculation for the unemployed poor…. Thus, euthanasia of the weak and sensual is possible. Once [these] principles … animate the predominate classes of the new time, it will be permissible, and I have little or no doubt that in the future it will be planned and achieved.”

One of those animated in the “new time” was Adolf Hitler.

Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, into a world in which anti-Semitism was already a force. His racial prejudice against Jews was not novel. In the West it went back to at least the 16th century when German theologian Martin Luther declared Jews “a plague, a pestilence…. They let us work in the sweat of our nose to earn money for them while they sit behind the oven, lazy, let off gas, bake pears, eat, drink, live softly and well from our wealth.”

Eugenics and Darwinism had caught on as a scientific curiosity by the time of Hitler’s birth. Darwin’s cousin, Francis J. Galton, helped launch the English crusade to abolish human inferiority by writing in 1863 that the problem “was so clean cut and so dire as to warrant state intervention of a coercive nature in human reproduction.” His suggested social planning methods included segregation, deportation, castration, marriage restrictions, and compulsory sterilization.

America’s finest universities and most respected scientists were involved in teaching and exploring eugenics by the time World War I erupted in Europe. Hitler, then 20 years old and a corporal in the German Army, spent three months recuperating in a Pomeranian hospital after being severely gassed in the trench warfare of 1918. Appalled at the large numbers of psychological casualties he witnessed among his fellow soldiers, he came to the conclusion that his nation had grown weak and corrupted through dysgenics, the inclusion of degenerate elements into the nation’s bloodstream.

In 1924, while serving time in Landsberg Prison for political mob action, he fed his obsession with human breeding by poring through publications and textbooks that extensively quoted American eugenics stalwarts like Leon Whitney, Madison Grant, Henry H. Laughlin, and others.

In 1925, he published Mein Kampf, which contains the core of his vision to build an Aryan “super race” through proper breeding and the physical destruction of “inferior” categories such as the Jews. It became one of the most influential books of the 20th century.

“There is today one state,” he wrote, “in which … an effort is made to consult reason at least partially. Of course, it is not our model German Republic, but the United States.”

The eugenics movement in America received impetus and cash support throughout the early 20th century from a conglomerate of professional, charitable, political, corporate, and government entities such as the Rockefeller Foundation, the Harriman railroad fortune, the Carnegie Institute, the U.S. State Department’s Vital Statistics Bureau, and many other advocacy groups drawn from child welfare, prison reform, education, clinical psychology, world peace, and immigration rights. “Superiors,” went the argument, should contemplate action against “inferiors” for the greater good of society and mankind.

More than 40 major universities and institutions offered eugenics instruction. A popular high school text by George William Hunter, A Civic Biology, railed against unfit families “spreading disease, immorality, and crime…. [T]hey take from society but they give nothing in return. They are true parasites.”

The Harriman railroad fortune paid charities in New York and other crowded cities to seek out the “unfit” and subject them to deportation or sterilization.

Author H.G. Wells described “meaningless, aimless lives which cram this world of ours…. Such human weeds clog up the path, drain up the energies and the resources of this little earth. We must clear the way for a better world, we must cultivate our garden.”

In 1921, Margaret Sanger went to work “cultivating the garden” by founding the American Birth Control League, which eventually evolved into Planned Parenthood and the International Planned Parenthood Foundation. One of it’s purposes was to “improve” the overall population by discouraging the “unfit” from reproducing.

“The feeble-minded, the syphilitic, the irresponsible, and the defective breed unhindered,” she explained. “The vicious cycle of mental and physical defect, delinquency and beggary is encouraged by the unseeing and unthinking sentimentality of our age…. I think the greatest sin in the world is bringing children into the world [who] have no chance to be a human being practically.”

For many eugenicists, sterilization seemed to be the most appropriate course of action. The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) and its laboratory complex founded with Carnegie Institute funding at Cold Springs Harbor on Long Island estimated that 10 percent of the American population should have its bloodlines terminated.

Sterilization began as a voluntary process but became involuntary in 1907 when Indiana became the first jurisdiction in the world to mandate the procedure against the mentally impaired, poorhouse residents, and prisoners. Three more states ratified similar laws in 1909. In 1911, New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, who would become president the following year, signed into law a bill to join them. In 1913, former President Theodore Roosevelt announced his backing, declaring, “Society has no business to permit degenerates to reproduce their kind.”

Laws of forced sterilization, segregation, and marriage restrictions were eventually enacted in 27 states. More than 60,000 Americans were eventually coerced into sterilization, most of which occurred during the 1930s and 1940s. While the blind, deaf, epileptic, mentally retarded, and the “feeble minded” of both sexes were targeted, women suffered most: “bad girls,” the “passionate,” “oversexed,” and “sexually wayward.” Some women were forcibly sterilized because they had what authorities deemed to be an abnormally large clitoris or labia.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the legality of the laws in a 1927 case in which Carrie Buck had been forcibly sterilized. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in favor of the decision.

“It is better for all the world,” he noted, “if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit for continuing their kind…. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Social Darwinism in America inspired imitating cliques throughout Europe, most notably in Germany where the ethnic cleansing movement was gaining rapidly even before Hitler came to power. German eugenicists formed academic and personal relationships with the U.S. eugenics establishment, relied extensively upon American research and experiments, and together formed a closely knit network that published the racist newsletters and “scientific” journals such as Eugenic News that served as propaganda for the emerging Nazis. Soon to be dictator Adolf Hitler was listening.

“I have studied with great interest the laws of several American states concerning prevention of reproduction of people whose progeny would in all probability be of no value or be injurious to the racial stock,” he commented to a comrade.

In Madison Grant, author of The Passing of the Great Race, Hitler found a kindred spirit when Grant wrote, “The laws of nature require the obliteration of the unfit, and human life is valuable only when it is of use to the community and race.”

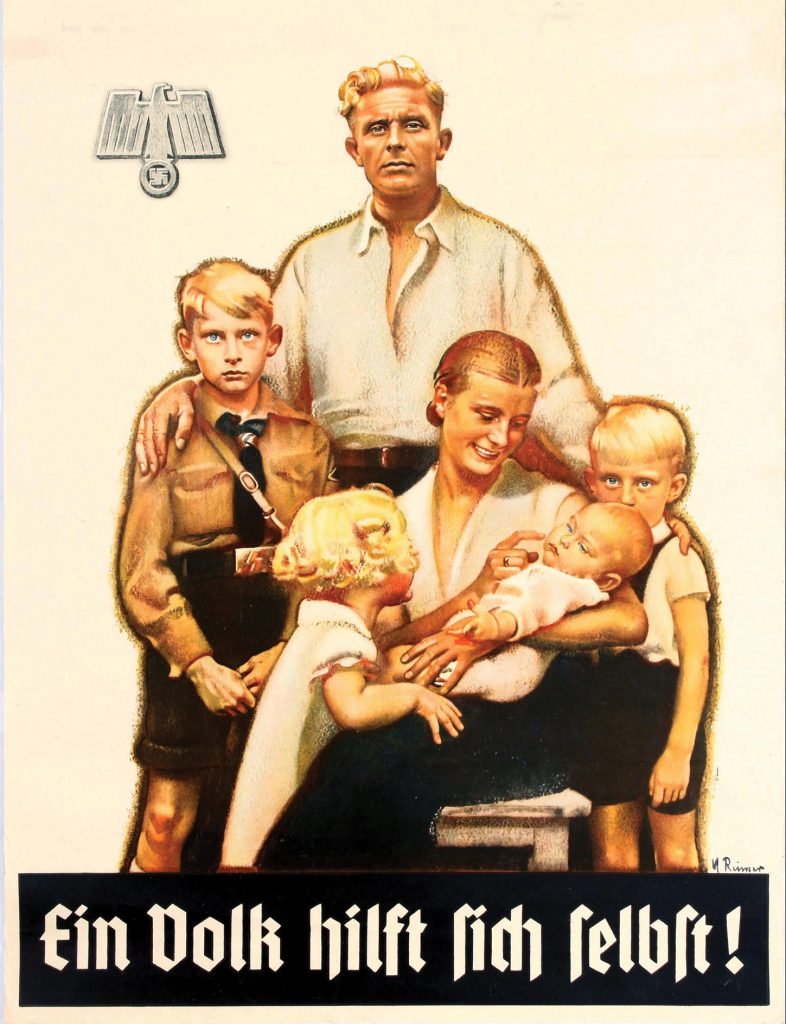

In Mein Kampf, Hitler echoed the sentiment: “It is thus necessary that the individual shall come to realize that his own ego is of no importance in comparison with the existence of his nation…. [T]he unity of a nation’s spirit and will is worth far more than freedom of the spirit and will of an individual.”

Individuals and institutions in the United States generously funded and supported German race biology prior to World War II. By 1926, for example, the Rockefeller Foundation had donated $410,000 (equivalent to $4 million in today’s currency) to hundreds of German eugenics researchers. The Carnegie Institute came in second place with large donations of its own, followed by a number of other corporations and foundations.

Racial theories were rife in German and other European universities where history courses taught that Jews were parasites who sapped the energy of any nation that tolerated them. Nazis preached that Jews controlled international financial networks that kept Germany in desperate poverty, had caused Germany’s defeat in World War I, and brought on the Great Depression of 1929 that collapsed Germany’s Weimar Republic.

Hitler liked to point out that he gained power in the 1932 elections legally and not at the point of a gun. In supplanting President Paul Von Hindenburg as chancellor, he sealed the National Socialist German Workers Party (NAZI) in power. Nazis began translating eugenics studies into action.

As the United States had done over two decades previously, Hitler started with compulsory sterilization for all people who suffered from allegedly hereditary disabilities such as feeble mindedness, schizophrenia, and epilepsy as well as those with physical and character defects like blindness, homosexuality, or severe drug or alcohol addiction. Included in his sterilization protocol was a “racist hygiene” proposal directed at “inferior racial groups” such as Gypsies, Slavs, and, especially, Jews.

Hitler’s sterilization efforts were modeled on laws already introduced in America and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Eugenics News in the United States evaluated the Nazi legislation as “clean-cut, direct and ‘model.’ Its standards are social and genetical. Its application is entrusted to specialized courts and procedure. From a legal point of view nothing more could be desired.”

Germany sterilized more than 400,000 Germans during the mid-to-late 1930s. Joseph Dejarnette, superintendent of Virginia Western State Hospital, complained in the Richmond Times-Dispatch that “the Germans are beating us at our own game.”

When eugenics leader C.M. Goethe returned from a fact-finding mission to Germany in 1934, he sent a letter of congratulations to E.S. Gosney of the Human Betterment Foundation.

“You will be interested to know,” he wrote, “that your work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinion of the intellectuals behind Hitler and his epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought…. I want you, my dear friend, to carry the thought with you for the rest of your life that you have really jolted into action a great government of 60 million people.”

Leon Whitney, president of the American Eugenics Society, and Madison Grant, author of The Passing of the Great Race, each received personal fan mail from Hitler congratulating them for their efforts in eugenics. The dictator further noted that Grant’s book was his “bible.”

In the Nazi Party’s official newspaper, Hitler also wildly praised President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” as an American form of fascism.

Future U.S. President John F. Kennedy toured Nazi Germany in the 1930s and returned with effusive praise for Hitler, recording in his diary, “I have come to the conclusion that fascism is right for Germany and Italy.”

Hostility to Hitler, he contended, stemmed largely from jealousy. “The Germans really are too good—that’s why people conspire against them.”

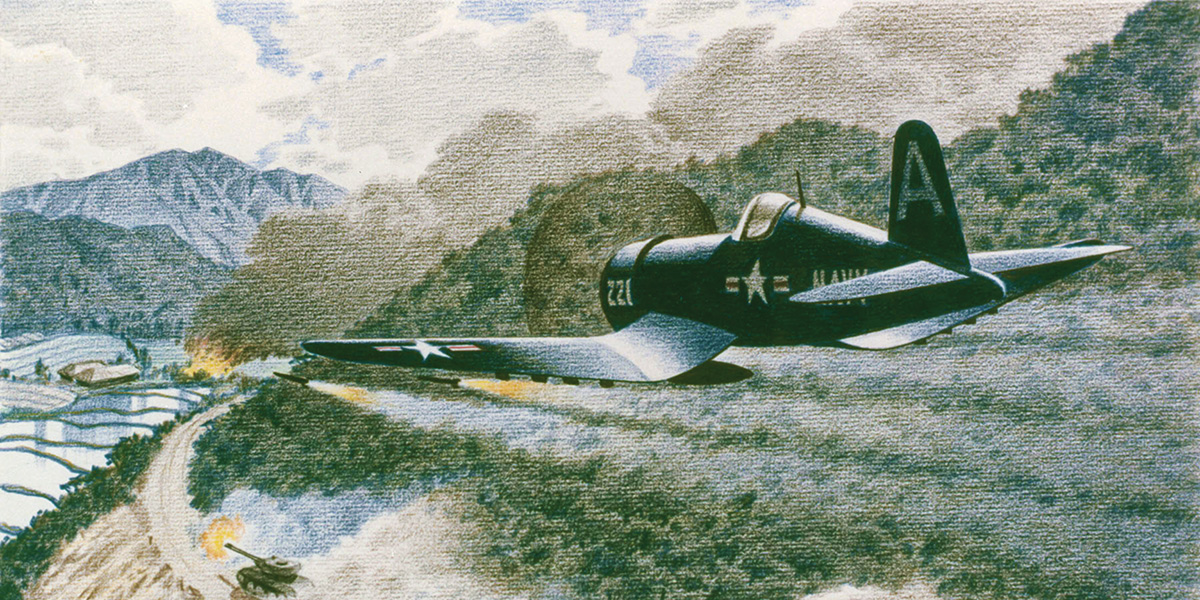

Even though JFK fought in World War II as a PT-boat commander in the Pacific, he retained his views of Hitler as late as 1945 when he described Hitler as the “stuff of legends…. Hitler will emerge from the hate that now surrounds him and come to be regarded as one of the most significant figures to have lived.”

Euthanasia to eliminate “social defectives” logically followed as the next step in the eugenics movement. It too was begun not by Nazis but instead by Americans who topped the field of international eugenics. The ethics of its deployment dominated the debate for at least two decades before Nevada approved lethal gas chambers for criminal executions in 1921.

While American society may not have been ready to apply such drastic measures to the general population, euthanasia was nevertheless already being practiced one patient at a time by some mental institutions and doctors. Medical lethality, willful neglect, and passive euthanasia applied to mental patients and newborn infants accounted for thousands of American deaths. One institution in Lincoln, Illinois, deliberately fed its patients milk from tubercular cows.

In 1918, Dr. Paul Popenoe, World War I Army VD Department, co-wrote the widely used textbook Applied Eugenics, which argued for euthanasia. “From a historical point of view,” he wrote, “the first method which presents itself is execution.”

In 1927, Planned Parenthood’s Margaret Sanger was among the first to accept and promote euthanasia as a program to secure a superior population. “The most merciful thing that the large family does to one of its infant members is to kill it,” she wrote. “Nature eliminates the weeds, but we turn them into parasites and allow them to reproduce.” [Editor’s Note: Margaret Sanger, and especially her views regarding eugenics, remains controversial today. However, she is also believed by many to have been an early champion of women’s reproductive rights.]

Physician Duncan McKim, author of Heredity and Human Progress, concurred that a “gentle, painless death … is the most humane method for preventing reproduction…. In carbonic acid gas we have an agent which would instantaneously fulfill the needs.”

In Eugenics, Marriage and Birth Control, New York urologist William Robinson decided, “The best thing would be to gently chloroform these children or to give them a dose of potassium cyanide.”

“If they are not fit to live,” chimed in British playwright George Bernard Shaw, “kill them in a decent humane way.”

During Hitler’s 12-year Reich that began in 1933, race science and the struggle for a “master race” remained a driving force behind his Nazism. Nazi doctors and scientists became the unseen generals to oversee the eugenics doctrines of identification, segregation, sterilization, euthanasia, and, ultimately, the mass extermination of Jews.

Concentration camps became an integral part of Nazi Germany, the first one built in 1933 almost immediately after Hitler attained power. These prisons soon sprang up throughout Germany and, after World War II erupted, in the nations Germany occupied. In them from 1933-1945 were cast not only Jews and other “inferior” races but also the mentally and physically disabled, homosexuals, and even children.

The Reich Committee for Scientific Research of Heredity and Severe Constitutional Disease shared responsibility with the National Coordination Agency for Therapeutic and Medical establishments, code named T-4, to eliminate “worthless eaters … life unworthy of life.” Beginning in 1939, “Children’s Centers” in 21 hospitals were designated the tasks of euthanizing deformed and retarded children. Hundreds of thousands of “inferior children” were thus executed.

Other patients selected to die were collected from hospitals, nursing homes, old-age homes, mental institutions, and other public custodial facilities and transported to euthanasia centers. Starvation and lethal injections were first used. Eventually, perhaps anticipating the Holocaust, the method of choice became gassing with carbon monoxide or with cyanide gas known as Zyklon B. Approximately 250,000 people were thus done away with by 1945.

Leon Whitney of the American Eugenics Society observed how “while we were pussy-footing around … the Germans were calling a spade a spade.”

The “Jewish question” still headed Hitler’s itinerary. The Nuremberg Laws on Citizenship and Race enacted in September 1935 accelerated the nation’s anti-Semitic campaign by, among other restrictions, revoking Jewish citizenship in the Reich, prohibiting Jews from marrying Aryans, and excluding Jews from schools, libraries, theaters, and public transportation.

“Today, I will prophet again,” Hitler announced. “If international finance Jewry should succeed once more in plunging the people into a world war, then the consequence will not be the Bolshevization of the world and a victory of Jewry, but on the contrary, the destruction of the Jewish race in Europe.”

In April 1938, Germany annexed Austria. Czechoslovakia fell in March 1939, followed the same year by German troops invading Poland, which prompted Britain to declare war on Germany. Hitler invaded France in 1940, then Norway. In 1941, Hitler double-crossed Stalin and attacked Russia.

Allied and Axis powers continued to line up until the war ultimately stretched around the globe. The United States entered the conflagration after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Thousands of Jews had already been butchered when Hitler ordered SS Security Chief Reinhard Heydrich and Reich Marshal Hermann Göring to draft “an overall plan of the organizational, functional and materiel measures to be taken in preparing for the implementation of the Final Solution to the Jewish question.” On January 20, 1942, a group of 14 of the most powerful Nazi bureaucrats met in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee to implement a solution.

The principal outcome of the Wannsee Conference was a policy by which all Jews would be rounded up and evacuated to occupied territories in the East, primarily in Poland. While the more able bodied would be conscripted for slave labor, all were eventually destined to be liquidated in production-line extermination camps already planned or being constructed in Auschwitz, Chelmo, Balzac, Sobibor, Majdanek, Treblinka, and Lublin. The Holocaust had started.

The first methods of killing were primitive, consisting of mass open-air shootings and disposing of the corpses in ravines or quarries. Mass shootings evolved into gassing with carbon monoxide in the backs of airtight vans, then to gas chambers using Zyklon B and incineration of the bodies in ovens. Groups of musicians sometimes played popular tunes while Jews were being gassed. These death factories continued unabated until the approach of American and Soviet armies in 1945.

Rudolf Hoss, commandant of Auschwitz, took great pride in his full-production extermination rate of 16,000 per day. During the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials following the war, Hoss used the defense that he and the others were merely cogs in a large machine. In memoirs posthumously published, he asserted, “I was completely normal … even when I was carrying out the task of extermination I lived a normal life.”

So did thousands of officials, policemen, rail workers, and others throughout Europe who knew what was happening but nonetheless either ignored it or helped keep the assembly line running. The Holocaust represents as much the collective will of Germany as it did Hitler’s. Smothered by the collective, no one person feels guilty or responsible for deeds committed by the whole.

Significantly, the New York Times noted in a piece about the Nazi era that the most ardent supporters for Hitler’s eugenics and euthanasia policies consisted of college and university students, professors, and the general run of so-called intellectuals. “Nazi death camps,” the Times summarized, “were conceived, built and often administered by PhDs.”

In his foreword to Jerry Bergman’s Hitler and the Nazi Darwinian Worldview, Doctor David Herbert warned that the world has not endured its last genocide.

“Events happen because they are possible,” concluded Holocaust scholar Yehuda Bauer. “If they were possible once, they are possible again. In that sense, the Holocaust is not unique, but a warning for the future.”

Charles Sasser is the author of the classic book on sniper warfare titled One Shot-One Kill. He has written dozens of other books and articles and appeared on numerous television networks including ABC, Fox, the History Channel, and CNN. He is a veteran of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Special Forces. He resides in Chouteau, Oklahoma.