By Patrick J. Chaisson

“This was war deluxe,” observed Brig. Gen. Frederic B. Butler as his command car entered the French village of Quincon during Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of France in the country’s southern region, in August 1944. Jubilant civilians filled the streets of Quincon, tossing flowers, fruit, and bottles of wine to the passing American G.I.s, who had just liberated them from two years of brutal German occupation.

While Butler certainly appreciated their emotional response, he wished these celebrating villagers would clear a path so his tanks and trucks could keep moving forward. A warm August sun had already grown low in the sky, and many miles still separated Butler from his objective for the night.

Things were going well for the general’s Provisional Armored Group on this first day of its mission. The weather was excellent, roads adequate, and resistance—save for a few isolated German strongholds—minimal. By dusk, Butler’s 3,000 men and 1,000 vehicles had dashed 45 miles behind enemy lines without suffering a single casualty.

The Origins of Operation Dragoon

Beginning on August 18, 1944, the soldiers of Task Force (TF) Butler made a bold attempt to cut off the retreating German Nineteenth Army in Southern France. These hard-driving combat troops overcame significant challenges of supply, organization, and communications throughout their four-day operation. But were they prepared to meet the dreaded German Mark V Panther tanks that awaited them at a crossroads town named Montélimar.

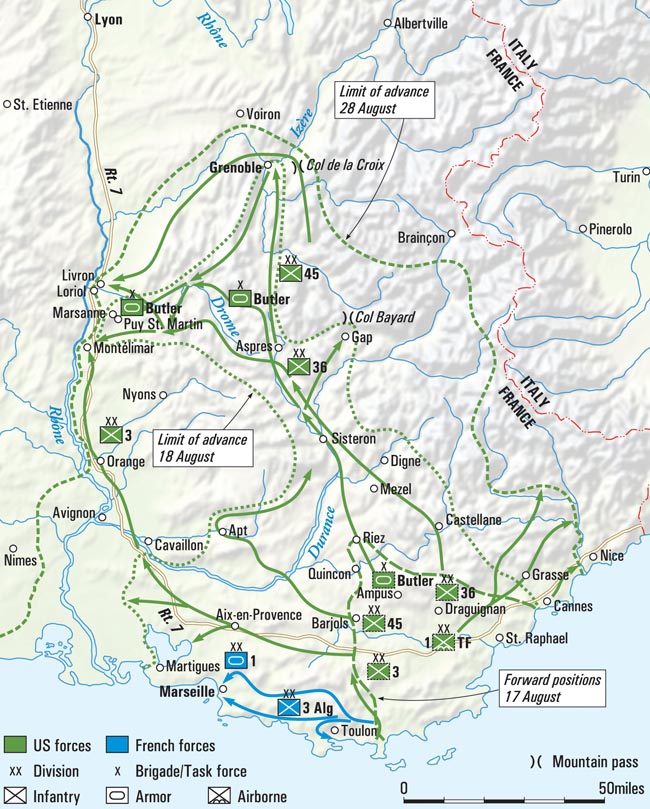

The idea of a fast-moving exploitation force first came to U.S. VI Corps commander Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott in his Naples headquarters on August 1, 1944. Truscott was then making final preparations to land three American divisions along the French Riviera as part of Operation Anvil (later renamed Operation Dragoon). Those outfits—the 3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions—were all largely foot-mobile. To chase down and destroy a fleeing enemy, VI Corps would require motorized units.

One such formation was already scheduled to land as part of Operation Dragoon. This organization, a Free French armored combat command named CC Sudre, had been designated VI Corps’ “floating reserve.” For political reasons, though, Truscott could not touch it. The gravelly-voiced general feared that French commanders would demand CC Sudre be returned at any moment for their own operations, thus stripping VI Corps of its mechanized spearhead, yet nothing prevented Truscott, an ex-cavalryman, from creating a highly mobile force of his own.

Truscott “planned to constitute a provisional armored group from elements of the [VI] Corps,” explained General Butler, then serving as assistant corps commander. “Turning toward me, he added ‘And if there is such a force, I want you to command it.’” Butler, a 47-year-old career soldier, had just been handed an enormous responsibility. He first put these operations and logistics experts to work preparing what he later described as a “detailed map reconnaissance of routes, terrain appreciation, air-ground cooperation, Maquis (French Resistance) liaison, and most pressing of all, a communication plan.”

The 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, VI Corps’ “eyes and ears,” was known as an aggressive, well-armed, and highly mobile combat team. It also possessed an especially robust radio network, onto which Butler superimposed his headquarters. The 117th consisted of three reconnaissance troops (A, B, and C), a self-propelled assault gun troop (E), and a company of light tanks (F). There was no Troop D. Significantly, Troop E had recently traded its M8 75mm assault guns for six new M7 105mm self-propelled howitzers. In command was Lt. Col. Charles J. Hodge.

Attached from the 36th Infantry Division (ID) was Lt. Col. Charles J. Denholm’s 2nd Battalion, 143rd Infantry Regiment, its riflemen riding to battle in 2½-ton trucks. Providing armored support were 31 M4 Sherman medium tanks belonging to Lt. Col. Joseph G. Felber’s 753rd Tank Battalion (minus Companies A and D), as well as 12 M10 gun motor carriages from Company C, 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The 59th Armored Field Artillery (AFA) Battalion, under Lt. Col. Joseph C. McCain, delivered indirect fire support with its 18 M7 howitzers, while Company F, 344th Engineer General Service Regiment, worked to maintain roads, bridges, and river crossing sites. Support units included Company C (Reinforced) 111th Medical Battalion, the 3426th Quartermaster Truck Company, and a detachment of mechanics from the 87th Ordnance Company.

The Provisional Armored Group’s organizational structure closely resembled that of an American armored combat command, with one key difference. Unlike a combat command, TF Butler had assigned to it a full cavalry squadron. These reconnaissance troopers, equipped with jeeps and M8 armored cars, could rapidly scout the column’s route of advance, secure its flanks, and keep enemy combatants occupied until infantry, armor, and artillery joined the fight. Just as importantly, their reliable FM transceivers were able to keep unit commanders continually updated on the tactical situation.

“The Best Invasion I Ever Attended”: the Allied Invasion of Southern France Officially Begins

Still unsolved, however, was the issue of long-range communications. Task Force Butler would be operating hundreds of miles from Truscott’s headquarters, well beyond the range of any radio in the 117th Cavalry’s inventory. A large SCR-299 transmitter was needed, but VI Corps had none to spare. This shortfall later nearly doomed the operation at a most critical time.

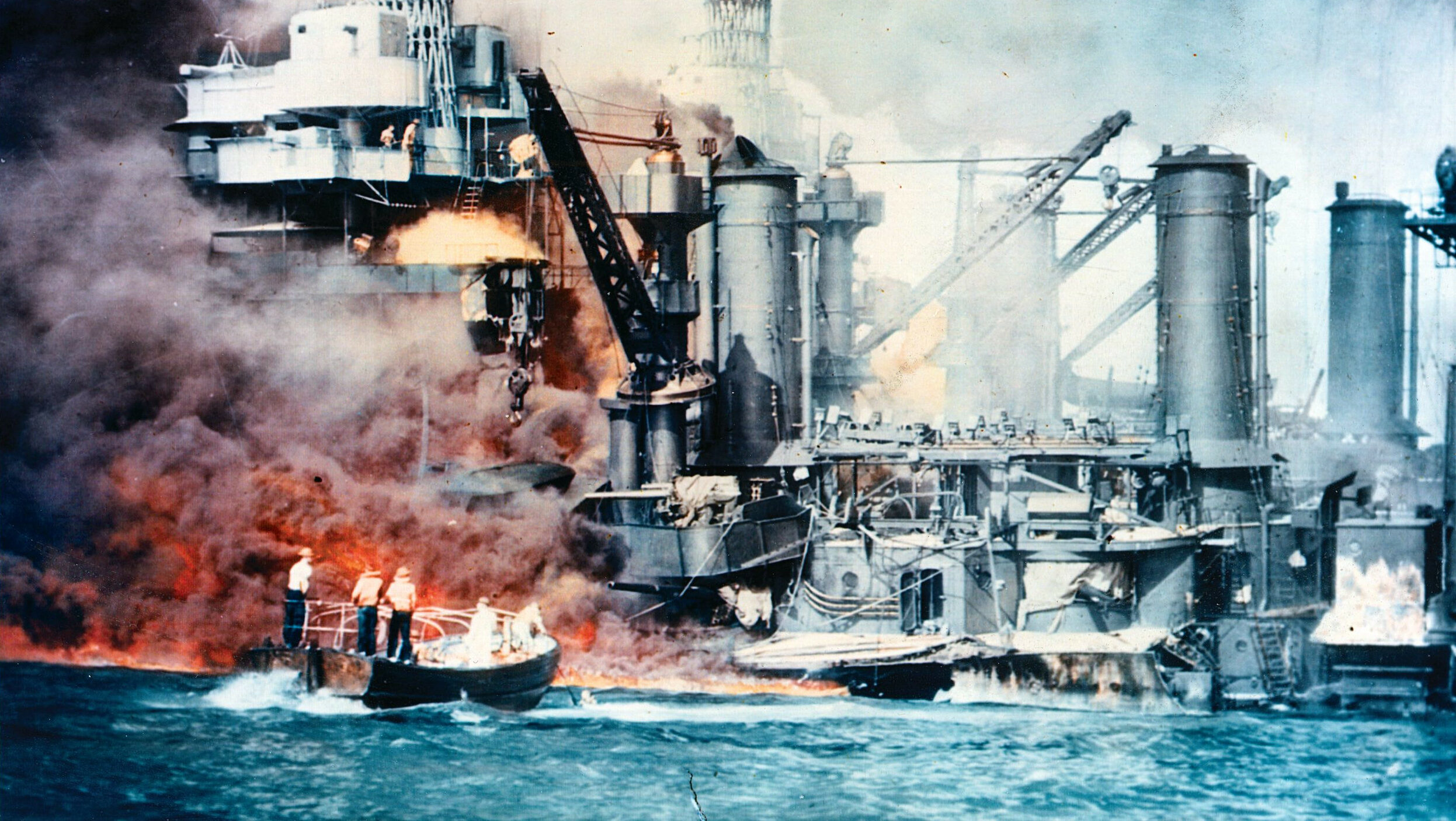

The Allied invasion of Southern France took place on August 15, 1944. Allied landing craft put ashore 66,000 soldiers and 6,500 tactical vehicles along a 30-mile stretch of the French Riviera between the cities of Toulon and Cannes. Another 9,000 paratroopers and glider troops were dropped 12 miles inland near the town of Le Muy.

The VI Corps had its beachhead firmly under control by nightfall with casualties numbering less than 500 men killed or wounded. Everyone who participated in the landings, from Maj. Gen. Truscott to the lowest-ranking foot soldier, remarked how easy it all seemed to be. Cartoonist Sergeant Bill Mauldin called Operation Dragoon “the best invasion I ever attended.”

Mauldin’s viewpoint was not shared by Nazi Germany’s supreme leader. “August 15th,” noted Adolf Hitler, “was the worst day of my life.” Hitler had ample cause to lament. The Allied thrust into Southern France threatened to maroon nearly 300,000 of his soldiers now caught between General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s rampaging armies in Normandy and the German frontier. Those troops had to be pulled back before enemy columns advancing from Normandy and the Riviera could close off their last routes of escape.

There was no time to lose. Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (or OKW, the German High Command) directed its forces stationed in Southern France to begin an immediate retreat. Units occupying the port cities of Marseilles and Toulon, however, were told to defend “to the last man.” Other outfits could not comply as they had already been wiped out by the Allied invaders.

The man responsible for executing the hazardous withdrawal of the German forces that might actually escape was General Friedrich Wiese, commander of the Nineteenth Army. From his headquarters in Avignon on the Rhône River, Wiese issued orders to the six infantry divisions under his command that were not affected by Hitler’s “last man” decree. Two of these divisions, the 148th and 157th, were to head east and seek safety astride the Franco-Italian border. The remaining four—the 189th, 198th, 338th, and 716th, all based west of the Rhône—were to concentrate near Avignon before moving north into Germany.

Wiese’s most powerful formation, the 11th Panzer Division, was also available for orders. Led by battle-tested Lt. Gen. Wend von Wietersheim, the “Ghost Division” was then billeted near Toulouse, 200 miles from the Allied landings on the French Riviera. It had been placed there to rest and reconstitute after a three-year tour of duty on the Eastern Front. And while Wietersheim was forced to send most of his Mark IV medium tanks to Normandy earlier that summer, the 11th Panzer Division had in operation 57 Panther tanks mounting superb 75mm main guns and ready to fight alongside the division’s veteran panzergrenadier, reconnaissance, and motorized artillery battalions by mid-August.

With invasion imminent, Wietersheim’s command set out on August 13 to join the rest of the Nineteenth Army at Avignon. To avoid the attention of prowling Allied fighter-bombers, all movement took place after dark whenever possible. It took the Ghost Division six nights to complete this road march, and another two to ferry its Panthers across the Rhône.

Despite dropped bridges, a crippling fuel shortage, and frequent interference from roving bands of French Resistance fighters, the Nineteenth Army initiated its retreat just as OKW ordered. Additional directives further specified its route of march north along the valley of the Rhône. The 11th Panzer, along with riflemen from the 198th Division, would serve as a powerful rear guard, keeping Allied attackers at a respectful distance from General Wiese’s main body.

OKW transmitted its comprehensive withdrawal plans for Nineteenth Army in a series of enciphered radio messages beginning on August 17. Wiese received them about the same time as did a team of British cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, England. Within hours, these technicians had decoded and sent forward to Southern France all this crucial intelligence. Allied ground commanders now knew every detail of what the foe was doing in response to their amphibious assault.

Task Force Butler Receives it Orders: Take the High Ground North of Montélimar

It was time for Maj. Gen. Truscott to launch the motorized exploitation force he had created for just such a contingency. He summoned Brig. Gen. Butler to his command post at mid-afternoon on the 17th. “You will proceed to Sisteron (a town on the Durance River 90 miles inland),” Truscott directed, “and from there, be prepared to continue north to seize Grenoble or to turn west and seize the high ground north of Montélimar.” Lead elements of Task Force Butler would pass through the 36th Infantry Division’s front lines at dawn.

Task Force Butler’s briefing took place later that evening at an assembly area near Le Muy. It was presented in a standard format familiar to all who attended, even though they had never before worked with one another. General Butler began by outlining their mission. Staff officers then covered coordinating details: routes of movement, fire support priorities, resupply and maintenance matters. Butler closed the conference with a few parting thoughts on speed. He had told General Truscott his unit would reach Sisteron in three days—possibly two—and fully intended to keep that promise.

The region in which TF Butler was to operate measured approximately 6,645 square miles. Bounded in the south by the Mediterranean coast, by the French Maritime Alps to the east, and in the west by the Rhône River, the city of Grenoble marked its northern limit. This so-called “Grenoble Corridor” consisted chiefly of rolling terrain with forests and farmland largely intermixed. Several small to medium watercourses cut the landscape. Of these, the Durance River represented a major impediment to travel if its bridges were down. Good, hard-surfaced roads connected a network of small hamlets and villages. Larger population centers included Digne, Draguignan, Gap, and Montélimar.

Special attention was given to the area around Montélimar. Here the broad Rhône River Valley, squeezed by steep cliffs north of town, narrowed into the Cruas Gorge—better known as the Gate of Montélimar. German military traffic passing through the 10-mile-long “gate” would have less room to maneuver and become far more vulnerable to Allied attacks. If VI Corps could beat the Germans to this chokepoint and somehow manage to block it, Nineteenth Army might well be destroyed in detail.

Butler’s infantrymen, tankers, gunners, and cavalry troopers rolled out at 0500 hours on August 18, but managed to advance only a few miles before coming to a sudden stop. His lead echelon had encountered a massive roadblock erected by friendly soldiers. It took 30 minutes of furious effort to clear that barricade and continue the movement north.

Troop C Receives a German Surrender in Aups

Troop C, meanwhile, scouted the road network on TF Butler’s right (eastern) flank. As 2nd Lt. Joseph L. Syms’ 3rd Platoon approached a hamlet known as Aups, it took heavy fire from the mouth of a nearby grotto. While an attached M5A1 light tank returned fire, Syms’ recon men dismounted to flank the enemy strongpoint. Sergeant Robert C. Lutz saw three German officers with a white flag approach his position. Their commander wished to give up, they said, but only to an American officer. Lieutenant Syms then came forward to accept the surrender of LXII Corps commander Lt. Gen. Ferdinand Neuling and his entire 400-man staff.

“We uncovered a lot of papers and maps showing the area and its defenses,” Syms recalled. His troopers also seized “cognac, cameras, five civilian cars, Luger pistols, [and] tins of cigarettes.” Neuling was taken to the town square in Draguignan, where Butler found him under guard and “seated on a park bench having a nice, quiet, dignified weep.”

After ordering the despondent Neuling back to a VI Corps POW cage, Brig. Gen. Butler called for a situation update. Reports from the west indicated heavy fighting in the road hub of Barjols, where Troop A’s 3rd Platoon was pinned down by enemy infantry and self-propelled guns. Outnumbered, the cavalrymen wisely withdrew to safer ground. A rifle battalion from the 45th Infantry Division relieved them later that day.

Butler Receives Help from the Maquis

Meanwhile, Butler’s main body began to pick up speed. Major Harold J. Samsel, the 117th Cavalry’s operations officer, described their progress: “The French civilians were delirious with joy as town after town was liberated. Their genuine welcome and high enthusiasm was a sight to behold. Older people wept unashamedly with tears of joy. The younger men and women showered the American liberators with wine, melons, fruits, and other gifts.”

Now making their presence known were the Maquis, resistance fighters belonging to the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI). Lightly armed but courageous beyond measure, these irregulars time after time proved their worth as guides, ad-hoc infantry, and sources of intelligence. “Without the Maquis,” General Butler reflected, “our mission would have been far more difficult, if indeed not possible.”

The 59th AFA put aloft two Stinson L-5 spotter planes, flown by Lieutenants Robert R. Freeman and Edward J. Ingram, as aerial reconnaissance scouts to locate obstacles and enemy troop concentrations. Butler recalled how each pilot “would buzz a road and give his report to the advance echelon commander who then could sweep on if an ‘all clear’ was the report or act with swiftness where trouble existed.”

Observation aircraft did discover one trouble spot south of Quincon, where the Verdon River bridge had been blown. As Butler’s men watched in amazement, hundreds of Maquisards and local townspeople quickly gathered to construct a ford by placing flagstones flat across the river bed. The Americans continued on to reach their destination at Riez by 1800 hours.

While combat troops and their Maquis auxiliaries set up defensive positions, logistics personnel pushed forward with badly-needed fuel (task force vehicles consumed 15,000 gallons of gasoline per day). Having already advanced out of radio range with VI Corps headquarters, General Butler sent a courier bearing situation reports back by jeep. He also held a late-night meeting with his subordinate commanders and resistance leaders to issue coordinating instructions for the next day’s advance.

French operatives reported a Wehrmacht battalion at Digne, on Butler’s right flank. These soldiers represented a serious threat to the column’s line of communications and supply, so at first light, Troop B, augmented by FFI fighters, light tanks, and M7 assault guns, headed out across mountainous terrain for a 15-mile ride to their objective.

At Mezel, a small commune eight miles outside of town, German snipers delayed the Allied advance for two hours. Dismounted American scouts eventually managed to enter Digne, but they hurriedly fell back under a flurry of small-arms and machine-gun fire. A second attack by the Maquis also failed. Digne’s 650-man garrison capitulated only after reinforcements, a company each of medium tanks and motorized infantry, added their weight to a late-afternoon assault.

In the meantime, Butler’s main body—preceded by Troop A and their “eyes in the sky”—struck out for Sisteron. By now, his tanks and trucks were advancing by bounds, dashing from cover to cover once fast-moving reconnaissance elements cleared the route. This saved both time and fuel, but it did not prevent two U.S. warplanes from inadvertently strafing the column, despite a display of yellow smoke meant as a recognition signal. Tragically, 13 men and three vehicles were lost in this friendly-fire incident.

Crossing the Durance River over a bomb-damaged bridge at La Brillane, Troop A reached its day’s objective—Sisteron—by 1800 hours. Following closely behind was the rest of TF Butler, with the 753rd Tank Battalion’s Lt. Col. Felber in tactical control. Those elements involved in the action at Digne came up later that night to rearm and refuel before joining the outpost line.

Phase I Was Accomplished, but Long-Range Communications Were Still a Grave Concern

General Butler had achieved the first phase of his mission ahead of schedule and with minimal losses, yet many fresh concerns occupied his mind. He had run off his maps, and while civilian roadmaps might suffice for cavalry and armor, they were wholly unsatisfactory for precision artillery fire missions. Also, his truck drivers now faced a 125-mile drive to reach the nearest supply dumps.

Worst of all, General Butler still could not talk with higher headquarters. At dusk, a liaison aircraft from VI Corps landed, its pilot delivering a brusquely-worded message written by Maj. Gen. Truscott the night before demanding that he speed up. Recognizing his boss was operating with outdated information, he ignored the note. The communications situation improved when a long-range SCR-299 radio finally arrived at Sisteron later that evening. Skilled signalmen promptly installed it, and in no time the Provisional Armored Group was transmitting regular situation reports back to headquarters.

What Butler really needed, though, were orders from Truscott telling him to either keep driving north on Grenoble or turn west toward Montélimar. At 0500 hours on August 20, he sent his operations officer, Major Kermit R. Hansen, back in the corps liaison plane to get those orders, but the radio remained silent all day, and there was no sign of Hansen.

Now operating 100 miles behind enemy lines, the Provisional Armored Group was exposed to attack from any direction. After sunrise, General Butler redeployed his main force to more defensible ground near a crossroads town named Aspres. Acting on the counsel of Maquis advisors, he also sent two reinforced cavalry troops into a pair of key mountain passes. Troop C took the Col de la Croix Haute north of Aspres, while Troop A headed northeast toward Col Bayard. Before Troop A could occupy Bayard Pass, however, it would first have to clear the town of Gap. Ominously, the FFI said, Gap was held by 1,000 Germans, a threat that could not stand unchallenged.

Capt. Omer Brown’s Bold Bluff

Troop A, under Captain Thomas C. Piddlington, reached the edge of town at 1600 hours. Accompanying the recon men were about 100 maquisards and a light tank platoon, as well as two 105mm assault guns from Troop E. Also along was Troop E’s commander, Captain Omer F. Brown, who the day before had glibly talked some enemy riflemen at Ampus into laying down their arms without needless bloodshed.

Displaying a flag of truce, Brown jeeped into Gap to parley with its garrison commander. He brazenly declared that Allied soldiers had the town completely surrounded, and that 60 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers were even then en route to carpet-bomb it. The German officer remained unconvinced, so Brown returned to Troop A’s command post determined to further persuade his foe with some high-explosive diplomacy.

The captain ordered his assault guns to fire a 40-round barrage targeting a large radio tower set up on a hilltop south of town. Their first salvo topped the antenna, which brought out a flurry of white surrender flags. Brown’s bluff worked, and the Americans and the Maquis moved in to seize Gap by 1830 hours.

Once in town, Piddlington and the 130 men under his command discovered they had just captured 1,100 enemy troops. Many of these men were conscripted Poles, happy to be finally released from duty with the Wehrmacht. The G.I.s, anxious to continue on toward Col Bayard, simply deputized their Polish POWs as impromptu prison guards and sent the lot marching back to Aspres.

Meanwhile, the 13,000 residents of Gap celebrated their liberation in fine style. General Butler, who witnessed this jubilee himself, said the population “literally had gone mad” with joy. He could not share in their exuberance, however. The ever-reliable FFI reported another 1,000 German soldiers advancing from Grenoble, 50 miles to the north. Troop A would need help to halt them, so later that evening, a detachment of motorized infantry and medium tanks went forward to reinforce Bayard Pass.

Butler’s task force found itself dispersed all across the Sisteron-Aspres-Gap region, deep in no-man’s land and still without orders. Hard-driving supply personnel somehow managed to rush forward ammunition, rations, and especially fuel, but communications remained a problem. The big SCR-299 radio was working only intermittently, and Major Hansen had returned from VI Corps HQ empty handed.

Nevertheless, things were beginning to develop. That night, Butler encountered the 36th Division’s assistant commander, Brig. Gen. Robert I. Stack, who told him a relief column was on its way to Sisteron. Truscott, now informed of the bigger picture by highly classified ULTRA intelligence intercepts, finally decided where to send his Provisional Armored Group.

A Long, Treacherous Road Ahead: Butler Receives His Orders

At 0400 hours the next morning, VI Corps operations officer Colonel Theodore J. Conway arrived at General Butler’s command post with orders directing him to “move at first light 21 August with all possible speed to Montélimar. Block enemy routes of withdrawal up the Rhône valley in that vicinity. The 36th Division follows you.” Furthermore, Truscott wanted his lead elements to arrive there before nightfall.

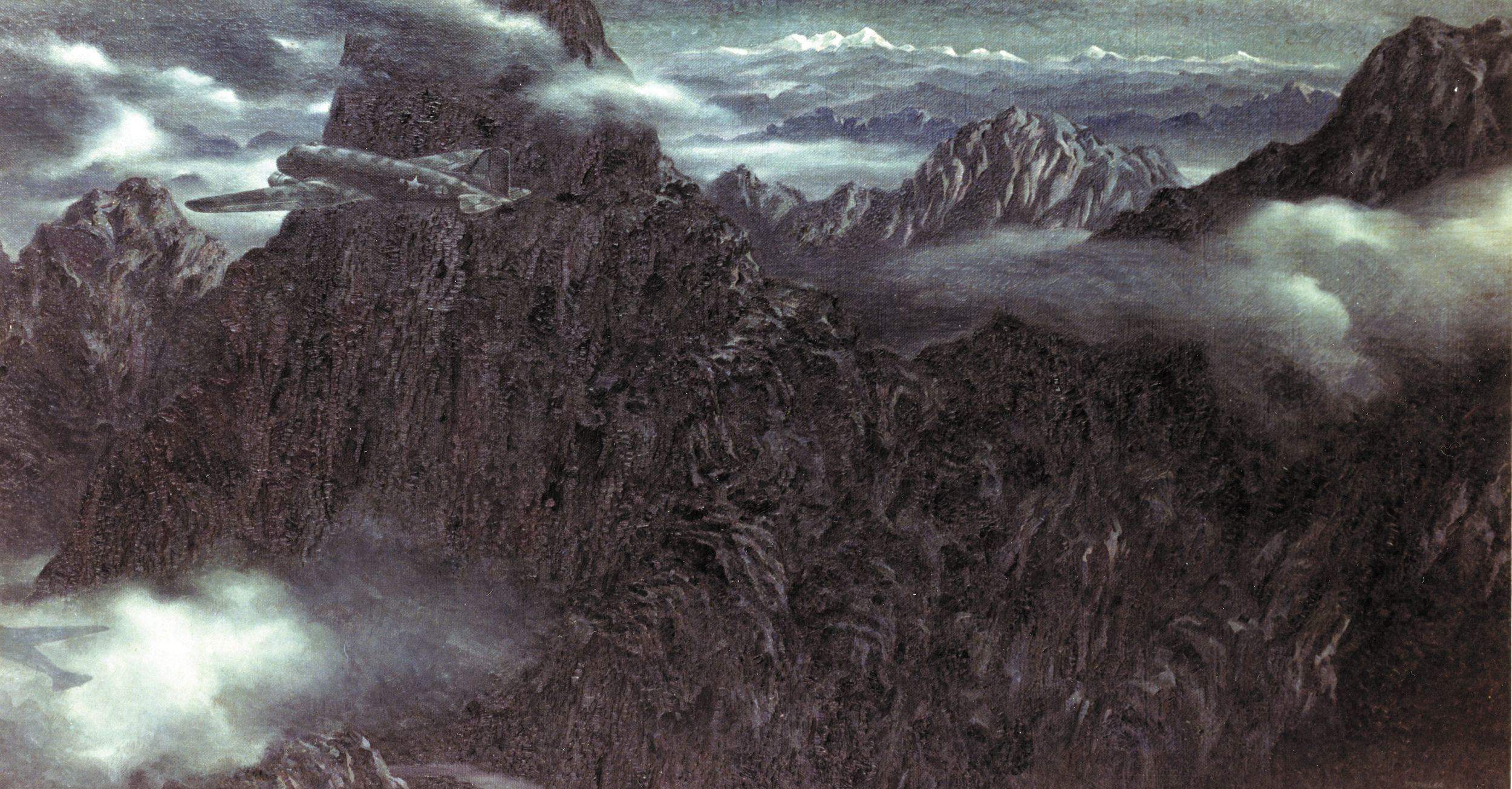

These instructions required American tanks, trucks, and howitzers to rapidly conduct a treacherous long-distance road march through hostile territory. “The route,” Butler remembered, “lay over a formidable mountain range with a twisty road cut into the side of the cliffs. Movement off the road would have been impossible. Our path could have been blocked in any one of scores of places, but no enemy action developed, nor had demolitions been emplaced.”

Troop B, under Captain John L. Wood, took the lead. By mid-afternoon, his men and vehicles had traveled nearly 90 miles to the outskirts of Montélimar. After dismounted scouts determined the town was too well defended for a hasty attack to succeed, Wood set up an outpost line and reported back to General Butler.

Next to deploy was Captain William E. Nugent’s Troop C, which followed the Drôme River to its confluence with the Rhône north of Montélimar. Near the village of Livron, Nugent’s troopers cut Route 7, the Nineteenth Army’s main avenue of retreat. The 2nd Platoon attacked a German supply column trying to ford the Drôme, while 1st Platoon raced north on Route 7 to overtake another enemy convoy. Troop C’s rampaging gun jeeps, light tanks, and armored cars destroyed at least 50 cargo trucks before a series of heavy counterattacks pushed them off the road at sunset.

As American combat forces approached the Rhône Valley, an abundance of lucrative targets greeted them. From three heavily-forested hilltops near Condillac, designated Hills 294, 300, and 430 for their elevation in meters, artillery spotters could cover a 15-mile stretch of highway overflowing with enemy foot soldiers and motor vehicles all fleeing the Allied advance. Butler’s tanks, set up along the mountain pass at la Coucourde, were even shooting at German planes operating from a nearby airfield.

Truscott’s “Cannae-like” exploitation maneuver had worked. Yet, as General Butler observed, “There is a vast difference between getting an advance guard of light, fast-moving armor into an enemy stronghold, and having a stranglehold on that enemy.” Could his small, thinly-spread command hold on until help arrived?

On August 22, TF Butler established itself in a 225-square mile “battle square” bordered by the Rhône River on its west edge, the Drôme in the north, and to the south by a small westward-flowing watercourse called the Rouibon. Enemy forces held Montélimar in the square’s southwestern corner, as well as two villages—Livron and Loriol—overlooking the mouth of the Drôme 15 miles northward. In between, all along the Gate of Montélimar, German and U.S. foot soldiers grappled for control of Hills 294, 300, and 430.

From those wooded heights, forward observers serving with Lt. Col. Joseph McCain’s 59th AFA saw before them “the dream of an artilleryman’s lifetime.” Hundreds of hapless horse-drawn wagons, bicycle troops, military motor transport, and commandeered French vehicles of every description clogged the roadways, easy targets for American 105mm howitzers. The 59th’s Stinsons, now employed in their intended role as aerial artillery spotters, directed fire onto a pair of northbound trains caught moving along the east bank of Cruas Gorge. Both trains, each carrying huge railroad cannon, were knocked out in short order.

All this sustained shooting left artillery ammunition stocks at dangerously low levels: 25 rounds per gun in most cases. Supply trucks were already on their way back to the beach for more, but that journey now totaled 470 miles round-trip. McCain had to forbid his gunners from firing after dark, making them conserve their precious munitions for the most dangerous targets.

out of hiding and taken prisoner.

The Ghost Division Heads for Butler’s Headquarters

One such threat was already making its presence known in the Montélimar battle square. Well-armed reconnaissance scouts from Lt. Gen. Wietersheim’s Ghost Division had on August 22 started to feel their way east along the Rouibon River. These soldiers, reinforced by five Panther tanks, tangled with Troop A near Cleon in mid-afternoon. Marauding Panthers quickly surrounded 3rd Platoon, forcing the men of Sergeant Mike Aun’s section to abandon their armored cars and escape on foot. The Germans then turned north, heading directly for General Butler’s headquarters at Marsanne.

Captain Piddlington, Troop A’s commander, was at that moment on his way back from Col Bayard with a column of armor and truck-borne infantry in tow. Mountainous terrain hindered FM radio communications, so one of the indispensable Stinsons dropped Piddlington a note of warning. He promptly deployed his outfit into battle formation and counterattacked.

In what Butler described as a “movie finish,” the two sides met in a fierce clash of arms near Puy St. Martin. “The German tanks which had crossed the Rouibon were destroyed,” he wrote, “the infantry were driven back and … several fires burned merrily where our guns had found trucks and light vehicles.”

Task Force Butler’s first duel with the 11th Panzer had ended in a victory for the overextended Americans. There was more good news: at 2200 hours, the 2nd Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment entered the battle square. These riflemen were the first of many 36th Division’s reinforcements to reach Montélimar. Two 155mm-equipped artillery battalions also came forward that night to provide additional long-range fire.

At 0900 hours on August 23, the commander of the 36th Division, Maj. Gen. John E. Dahlquist, arrived on the scene. This signified the end of General Butler’s mission, although Dahlquist asked him to remain in charge for the time being. By 1500 hours, though, the 36th had taken control of combat operations. One of Dahlquist’s first acts was to dissolve TF Butler and attach its units to his own command.

235 Miles, 3,500 German Prisoners, Dozens of Communities Liberated

The fighting near Montélimar would go on for another six days. At no time during this week-long battle did U.S. forces ever completely cut Nineteenth Army’s route of withdrawal. There were simply too many Germans and not enough Allied soldiers on the battlefield to fully accomplish Maj. Gen. Truscott’s grand vision. The Cruas Gorge was also just beyond range of friendly fighter-bombers, while chronic shortages of artillery ammunition, fuel, and trucks to carry those supplies considerably hampered VI Corps’ attempt to crush the retreating enemy.

Due in large part to the 11th Panzer’s well-executed delaying action, the Nineteenth Army extricated nearly 138,000 troops from the Allied trap at Montélimar. It did, however, have to abandon huge stockpiles of materiel and ordnance. In addition, thousands of irreplaceable cargo trucks, tactical vehicles, and artillery pieces had been smashed while trying to pass through the Cruas Gorge. These losses greatly diminished the combat power of Gen. Wiese’s army as it limped its way toward the German border.

In August 1944, a small but daring mounted command under Brig. Gen. Frederic Butler advanced 235 miles, captured 3,500 German prisoners, and liberated dozens of communities in Southern France during its four-day mission. Task Force Butler then won the race to Montélimar and contributed to the near-annihilation of an entire enemy field army. It is with good reason, then, that this epic gallop during the Allied invasion of France in the south has been characterized as “one of the most colorful and dashing ventures of the entire war.” (Dive deeply into the stories that defined the Second World War by subscribing to WWII History magazine.)

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer and historian who writes from his home in Scotia, New York.