By David A. Norris

As 18 elephant-drawn heavy guns of the British East India Company’s Bengal Artillery opened fire, Major John Fordyce’s troop of the Bengal Horse Artillery rushed their 9-pounders ahead of the infantry. They unlimbered between two mud- brick villages, with thick clay walls holding networks of houses and courtyards. Thought to be empty, the villages of Burra-Kalra and Chota-Kalra instead were held by Sikh troops. Their commander, Sher Singh, led the Khalsa, the army of the maharajah of the Punjab.

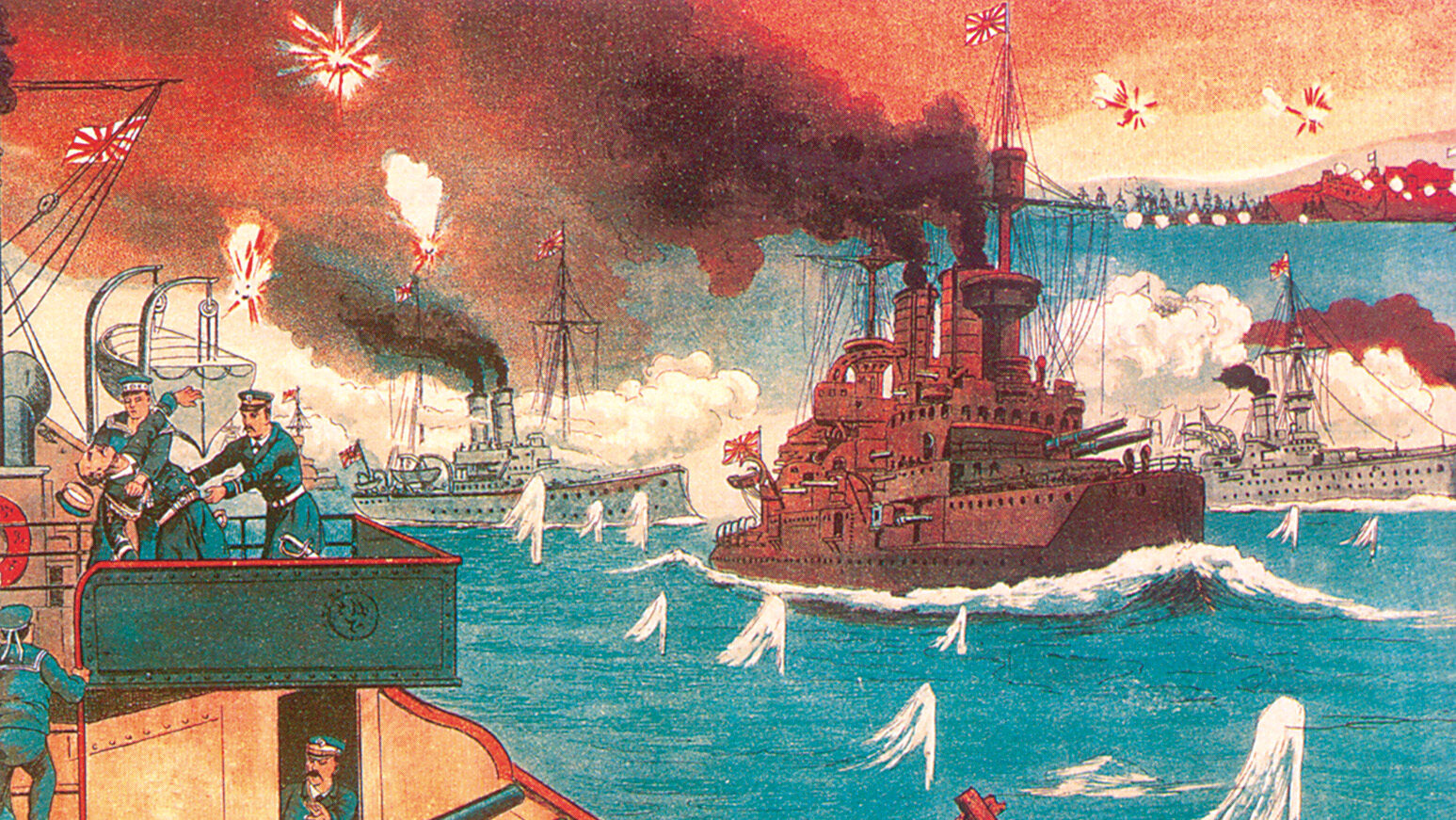

Firing from rooftops and loopholes bashed through the brick walls, Sikh foot soldiers poured fire into both flanks of the enemy battery. Horses and gunners fell, and the battery pulled back. The sudden withdrawal exposed the sepoys and British regulars holding the front line to enemy muskets and cannons. The reckless deployment of the British guns marked the beginning of the Battle of Gujrat, fought on February 21, 1849. The outcome of the pitched battle would decide whether the Sikh Empire of the Punjab would remain independent or would become the last region of India to come under British control.

India’s once powerful Mughal Empire was in its last years of decline by the 1840s. Most of the subcontinent was effectively under British control, either by direct rule or alliances with the monarchs of Indian states. These lands were ruled not directly by the British Crown, but by a vast private corporation, the British East India Company. The Company administered the government, ran a postal system, and also maintained armies that outnumbered most of those in Europe. Company territories were divided into three districts, called presidencies: Madras, Bengal, and Bombay. Each presidency had its own army, mainly of Indian troops with some regiments of Europeans. The majority of the Europeans were either British or Irish.

The last substantial section of India that was not under East India Company control was the Punjab. A district in northwest India, the Punjab lay strategically between the company-controlled Northwest Provinces and Afghanistan. During the 18th century, India’s Mughal Empire was in decline, and its control of the Punjab loosened. An alliance of Sikh rulers began to unify the region’s collection of Sikh, Muslim, and Hindu states into a single entity and sought independence.

At the turn of the 19th century, Maharaja Ranjit Singh consolidated power in the Punjab and ended Mughal control. Squeezed between the openly hostile Afghans and the quietly menacing British, the maharaja depended on his military force, an army known as the Khalsa.

Most soldiers originally had served as cavalry, the most prestigious arm of the Sikh military. The Sikhs undervalued infantry and artillery. The status of those serving in the two military branches was low, and they formed only small portions of the military.

All too aware of the power of the East India Company’s armies, Ranjit Singh launched an ambitious plan of modernization soon after 1800. While retaining large numbers of traditional Sikh cavalry, the maharajah built a new royal army patterned after the regulars of the East India Company and the European powers. At first he relied on former East India Company sepoys or Anglo-Indians with military experience. By the 1810s he hired European veterans of the Napoleonic Wars to train his regulars. His foundries made serviceable copies of British cannons for batteries of horse or bullock-drawn field artillery. Flintlocks replaced matchlock muskets among the regulars. By the late 1820s the maharaja’s regulars compared favorably with those of the European powers.

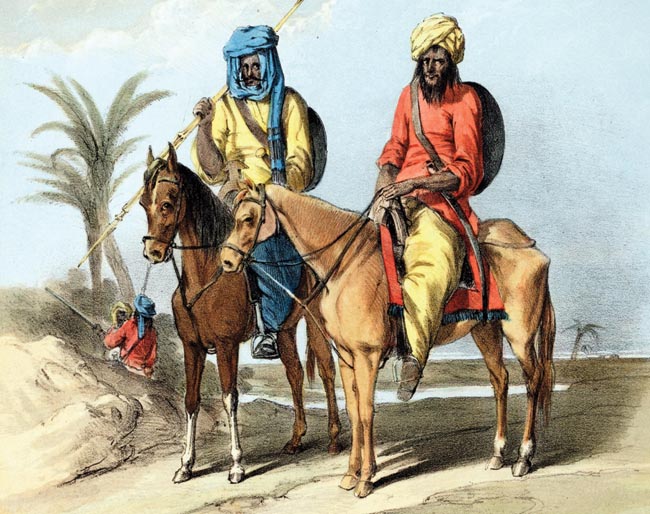

Although commanded by a Sikh monarch, the Khalsa included Muslim and Hindu troops, and some Ghurkas also served. Only the cavalry was completely Sikh. The Sikh cavalry was composed of regular regiments and gorchurras, which were irregular cavalry raised by aristocratic landowners. To balance potential power plays, the artillery was commanded by Sikh officers, but the gunners were Muslim.

With the aid of the Khalsa, Ranjit Singh ruled the last substantial portion of India not yet under British control or influence. Carefully maintaining neutrality with the British, the maharajah concentrated on his other rivals. He expelled the Afghans from his domains and captured Afghan-ruled territories, including Jammu and Kashmir, to add to his realm.

For a time, the British were much less worried about Ranjit Singh than they were about Afghanistan’s ruler, Emir Dost Mohammed Khan, whom they were convinced was plotting with the Russians to combine in an attack on India. With the consent of the Sikh regime, British forces passed through the Punjab on their way to invade the emir’s domains in the First Afghan War of 1839-1842.

Initially successful, the British captured the capital of Kabul and installed a new emir. But resurgent Afghans drove out the British and destroyed an army commanded by Maj. Gen. William Elphinstone in 1842. In retaliation, another British army recaptured Kabul. After destroying part of the city and freeing some prisoners, the British withdrew and Dost Mohammed regained his throne.

Stability ended in the Punjab with the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839. Several successors were murdered after brief reigns. Eventually Ranjit Singh’s five-year-old son Duleep Singh was installed as maharaja, with his mother Maharani Jind Kaur as regent.

The British, wary of the Punjab’s powerful army and the instability of the regime, bolstered their forces near the Punjabi border. Tensions rose until the First Anglo-Sikh War broke out from 1845-1846. After defeating the Sikh Army, the British demanded reparations and territorial concessions. The young Duleep Singh remained the nominal ruler, but his mother was ousted as regent and real control went to a British official known as the Resident. British troops were stationed in the Punjab. The Khalsa, once numbering more than 100,000 men, was ordered cut down to 32,000; that force was slashed yet again in a new treaty.

Conflict flared again after April 20, 1848, when Sikh troops at Multan killed two British officers. Multan was ruled by Diwan Mulraj, a Hindu vassal who owed allegiance to the Sikh maharajas. Governor-General James Andrew Broun Ramsay, Lord Dalhousie, sent a force under Maj. Gen. William Sampson Whish to Multan. Alongside Whish’s regulars and East India Company troops was a contingent of Sikhs under a high-ranking nobleman, Sher Singh.

In the northern Punjab, Sher Singh’s father Chattar Singh had been deposed as a provincial governor at British insistence. Chattar Singh began a revolt to overthrow the Punjab regime and establish a government without British influence. He persuaded Khalsa troops to join him, and many of the soldiers who had been forcibly dismissed from the service by the British joined his banner. The Sikh rebels made overtures to their old enemies, the Afghans. Messages also went from Chattar Singh to urge his son to join him.

On September 14 Sher Singh tossed in his lot with his father. He defected from Whish’s army, taking 4,500 men with him. With the defectors greatly strengthening the garrison of Multan, Whish halted siege operations to await reinforcements. Unable to come to agreement on an alliance with the ruler of Multan, Sher Singh withdrew his troops to join his father.

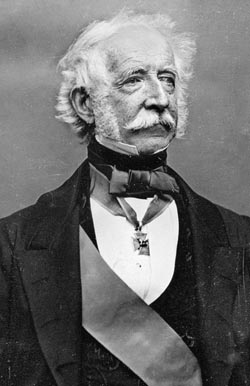

Lieutenant General Sir Hugh Gough, Great Britain’s commander in chief of India, took the field at the head of his army. Nearly 70 years old, the Irish-born Gough was a veteran of the Peninsular War and several British colonial wars. He made a point of sharing the dangers of battle. “I never ask the soldier to expose himself where I do not personally lead,” he wrote. On the battlefield, Gough was easily recognized by his long white hair and his flamboyant white battle coat. The coat made him conspicuous to the men he led under fire, despite the risk of drawing the aim of the enemy as well. Although Gough was popular among the rank and file, some officers deplored his recklessness in battle.

Gough and 20,000 troops crossed the Sutlej River on November 9 and entered Punjab. Sher Singh was known to be at Ramnagar, on the Chenab River. Dalhousie ordered Gough to wait until Multan fell before engaging the enemy, but Gough hastily moved to attack this Sikh force before it could unite with others.

On November 22, Gough’s army neared the south bank of the Chenab at Ramnagar. Some of the 14th Regiment of Light Dragoons dismounted. Searching for food, they started digging up a turnip field. They had little time to forage. Without waiting for a proper examination of the enemy defenses, Gough ordered the army to attack. A sergeant in the dragoons by the name of Clifton had just pulled up a large turnip; not wanting to lose it, he clapped it under his shako and rode off with his company.

As the battle unfolded, two heavy batteries of Sikh guns opened fire from the opposite bank, joined by another battery on an island in the river. Gorchurras, the Sikh irregular cavalry, crossed the Chenab.

Sikh regular cavalry resembled European dragoons or lancers, with Western-style military jackets and weapons topped off with Asiatic touches. The more numerous Sikh irregular cavalrymen wore their regular civilian clothing but often added protective armor of chain mail, plates, and heavily quilted clothing. Irregulars usually carried matchlocks as firearms, although they preferred using swords in combat. Lieutenant G.A. Bace of the 61st Foot noted how easy it was for the British to mistake the gorchurras for their own Bengal irregular cavalry.

Taking personal command of the British horse, Gough ordered the 14th Light Dragoons and the 5th Bengal Light Cavalry after them. Colonel William Havelock of the 14th led the charge, and the cavalry galloped all the way to the riverbank. Brig. Gen. Charles Robert Cureton, once an officer of the 14th Regiment, saw the cavalry was riding into a trap and rode to head them off. Cureton was shot dead before he could stop them, and Havelock was killed at the river. In the clashes with the Sikh cavalry, Sergeant Clifton took several sword cuts on his shoulders. His shako was slashed and hacked, but his head was safely protected by the turnip inside his headgear.

The Battle of Ramnagar ended with Gough holding the battlefield. Despite controlling the ground, he had accomplished very little. What is more, the attack cost him 150 men. Cureton and Havelock, both old veterans of the Peninsular War, were deeply respected officers who were sorely missed.

Heavily reinforced, Whish resumed his siege of Multan. The city fell on January 4, 1849, after heavy house-to-house fighting resulting in high death tolls of civilians and soldiers alike. Many of the regulars and Company troops who stormed into the city turned to looting and pillaging. The diwan and a few hundred soldiers remained defiant in the city’s battered citadel until January 22. Mulraj was sentenced to exile for the deaths of the two British officers the previous year.

Near the Jhelum River at Chillianwallah, Gough with 14,000 men encountered more than 30,000 men under Sher Singh on January 13, 1849. Officers interested in classical history knew that a dozen miles northeast of the battleground, Alexander the Great had crossed the Jhelum in 326 BC.

With a much larger army, the Sikh line overlapped both British flanks. Gough intended to launch an attack the next morning, but after the Sikh artillery opened fire in mid-afternoon, he ordered an immediate attack without waiting to assess the enemy position. His troops hacked their way through thick undergrowth to get at the enemy.

Lieutenant Colonel John Pennycuick’s brigade became separated from the other infantry. His regulars of the 24th Foot reached the Sikh lines. By some mistake, the 24th had been ordered to charge a Sikh artillery position by bayonet only, with orders not to fire. They broke through the enemy lines, but the Khalsa rallied and hurled them back with heavy losses. Pennycuick’s other regiments, the 24th and 25th Bengal Native Infantry, were also overwhelmed by the charging Sikhs. Pennycuick was killed in the fighting, as was his 17-year-old son Alexander, who was an ensign in the 24th. The brigade suffered 800 casualties. Each regiment lost at least one of its colors.

Some British successes elsewhere on the field were outweighed by the bungled attack of Lt. Col. Alexander Pope’s cavalry brigade. A semi-invalid, Pope had to be helped to mount a horse, and his vision was poor. He gave conflicting and confused orders until confronted by a Sikh cavalry charge. His misunderstood commands sent the brigade reeling in flight. Pope was mortally wounded.

Gough suffered heavy casualties in only three hours. His losses totaled 602 dead, 1,651 wounded, and 102 missing. His troops spiked several guns that could not be brought off and withdrew. Fortunately for him, the Sikhs also stopped the attacks and pulled back to the river.

Chillianwallah became a byword for failure. After the disastrous Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava on October 25, 1854, a worried Lt. Gen. George Charles Bingham, the Earl of Lucan, discussed the charge with Quartermaster-General Sir Richard Airey. The latter tried to reassure Lucan. “These sorts of things will happen in war,” he said. “It is nothing [compared] to Chillianwallah.”

Ramnagar had been bad enough, but Chillianwallah stirred a storm of criticism of Gough in the press and government circles. An effort was under way to replace Gough with a more deliberate and level-headed commander. Maj. Gen. Charles James Napier was appointed in Gough’s stead. Napier sailed for India to take up his new command.

Sher Singh tried without success to bait Gough into another battle. While the British commander bided his time, reinforcements joined the Khalsa. A booming 21-gun salute that startled the nearby British in their camp greeted the arrival of a Sikh force led by Sher Singh’s father, Chattar Singh. With them were 1,500 Afghan horsemen under a son of Emir Dost Mohammed Khan.

Soon it was the Sikh camp’s turn to hear an enemy 21-gun salute. On January 25 news reached the British that Multan had fallen. Whish’s troops, freed from the siege operations, would soon reinforce Gough’s army.

British estimates of the size of the combined Khalsa forces ran as high as 60,000 troops. It is probable this figure was highly exaggerated, but the Sikhs still outnumbered Gough and whatever troops might join him.

The soldiers of the Khalsa stripped the Chillianwallah region of food and began a 30-mile march east to the city of Gujrat on February 2. (This Gujrat, which is now located in Pakistan, is not to be confused with the Indian state of Gujarat). In the surrounding Gujrat district, they hoped to replenish the army’s rations in the countryside along the Chenab River. Ranjit Singh’s imperial capital of Lahore was only 75 miles from Gujrat. Taking the capital and its British garrison was a tempting goal for the army.

Gough followed the Khalsa into Gujrat; meanwhile, columns of British reinforcements marched to join him. On February 17 and 19 two brigades of Whish’s division joined the main army, followed by Whish’s third brigade on February 20.

This raised Gough’s army to 23,000 men. His cavalry division was commanded by Maj. Gen. Sir Joseph Thackwell. Whish, Sir Walter Raleigh Gilbert, and Sir Colin Campbell, each of whom held the rank of major general, commanded his three infantry divisions. Four regiments of cavalry and five regiments and a battalion of foot were British regulars. The bulk of the force was drawn from the Bengal Army, rounded out with some units from the Bombay Army. Most of these Company troops were Indian. All of the artillery belonged to the Bengal or Bombay Armies.

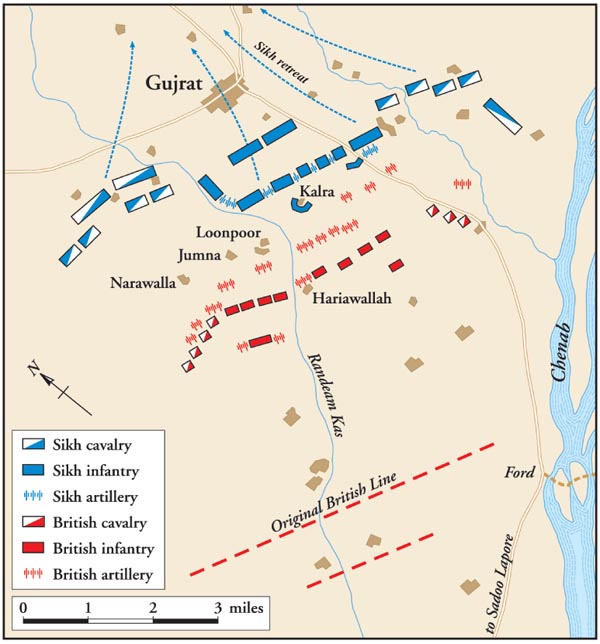

Mindful of the near disaster of Chillianwallah, Gough and his commanders spent February 20 planning the next day’s battle. Sher Singh held a line south of Gujrat (often spelled with variations such as Goojerat in contemporary accounts) about five miles west of the Chenab River. “This is a rich and beautifully fertile countryside,” wrote Ensign Daniel Augustus Sandford of the 2nd Europeans (the Bengal Army’s 2nd Light Infantry Regiment). “For miles and miles round there is nothing but luxuriant green corn fields.”

Sher Singh aligned his infantry between two nullahs (dry riverbeds), but neither presented a serious barrier to the attacking forces. On their right, the then-dry Dwala was described as “a deep sandy-bedded rivulet” by a British officer. The Katehlah, the nullah shielding the Khalsa left, had a shallow flow of water. Yet it was so insubstantial that a British observer thought that the left flank was in the air; that is, completely unprotected.

British officers later believed that the Khalsa was overconfident after the outcome of the Battle of Chillianwallah. The three miles of terrain between the nullahs was level plain, and little provision was made for defensive works. Most of the Khalsa heavy artillery had been sent elsewhere, but 59 guns remained for placement along the line of infantry. The Sikh cavalry was posted on the flanks, separated by the nullahs from the infantry.

W.G. Mainwaring, then a subaltern of the 1st Bombay European Regiment, recalled the preparations on the morning of February 21. “By 5 am the whole camp was alert and stirring—tents and baggage being packed in one direction [and] officers eating their breakfast on the ground in another—everything and everybody in a hurry, but at the same time little or no noise,” he wrote.

When Gough’s troops approached from the south, they heard drums beating within the Sikh lines. Far to the northeast, the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas overlooked the plain. “As the enemy’s masses very early had taken up their position, there was no dust of moving columns to cloud the purity of air and sky,” recalled staff officer Captain Henry Durand. “A looker-on might have thought the army drawn out on some gala occasion for the baggage being packed in safety … the force moved free of encumbrance, and the whole had the appearance of a grand review.”

The British force was divided by the Dwala. The larger portion to the right of the Dwala, with two brigades each from the divisions of Gilbert and Whish, would strike the Sikh left and center. They would push back the enemy onto their right, where the British left under Major Gen. Sir Joseph Thackwell would attack. Cavalry brigades, moving en echelon, protected the British flanks.

When the British line reached the village of Hariawallah, the Sikh batteries opened up. Firing at a range of 2,000 yards, the initial Sikh bombardment had little effect. The harmless firing revealed to the British gunners where the Sikh batteries were located.

As the British moved closer, the enemy fire took more effect. Sandford’s regiment advanced a quarter of a mile, and “round shot flew about us, and ploughed up the ground in all directions,” wrote Mainwaring. “All this time the fire was very hot upon us, carrying three men off at a time, shells bursting over us, or burying themselves in front, scattering the earth in our faces. There was a constant line of doolies from our regiment to the hospital, as, one after another, the men were carried off,” he wrote.

A doolie was a covered litter, used in India both for civilian travel as well as transporting the wounded. The doolie was fitted with a cot suspended from the long pole borne by the bearers. A cloth canopy and curtains protected the patient from heat and dust.

With large East India Company contingents from the Bombay and Bengal Armies, Gough had nearly twice as many guns as Sher Singh. At 9 am, the ground shook as nearly 100 Bengal and Bombay guns opened fire. Ten 18-pounders and eight 8-inch howitzers were brought up to close the distance to the enemy. Elephants pulled the big guns, and bullocks drew the ammunition carts.

Several troops of horse artillery rushed far ahead of the line and unlimbered closer to the enemy. One company from each foot regiment was assigned to move ahead and cover the gunners.

Shielding Sandford’s regiment was Major John Fordyce’s troop of the Bengal Horse Artillery. The troop’s 9-pounders took position ahead of the infantry between the fortified villages of Burra-Kalra (Great Kalra) and Chota-Kalra (Little Kalra), which were in advance of the Khalsa’s main line. Fordyce’s gunners “suffered dreadfully— every shot pitched right into them,” wrote Mainwaring. “Twice had they to retire to the rear for fresh horses and men.” In holding their position, Fordyce’s troop suffered the highest losses of any Bengal Artillery unit at Gujrat. Eight enlisted men and 25 horses were killed, and another 23 men and 13 horses were wounded.

To counter the Company’s heavy guns, the Khalsa had only two 16-pounders and one 18-pounder. The rest of their guns were smaller field pieces. The muzzles of some of the Sikh guns had been sawed off, enabling them to keep using pieces damaged in previous battles. For two and a half hours, Gough’s artillery tore gaps through the Sikh ranks and their artillery. Occasionally, a tumbril exploded, throwing up a puff of smoke visible from the British lines. Return fire gradually slackened as more and more of the Khalsa guns were knocked out of action.

The Khalsa troops pulled back to a new line closer to the city, behind Burra-Kalra and Chowta-Kalra. These villages, each a tight network of adobe houses and small courtyards divided by narrow streets, served as redoubts for Sher Singh’s army. After picking off Fordyce’s horses and gunners, they now waited for the main attack of the British and sepoy regiments.

For much of the morning, Gough held his forces in check. A tale would spread across British India that early in the morning Gough climbed a ladder into a tower to survey the battlefield. Expecting him to yield to the temptation to send his soldiers in before waiting for the artillery to soften up the enemy line, the staff officers took away the ladder. Gough was stranded in the tower long enough for the guns to finish their work. The story was disproven, but just the same, it catches something of the impression many officers had of Gough.

Gough pleasantly surprised some of the officers by leaving his gunners to their work for a good part of the morning before ordering two brigades to attack the fortified villages. Colonel Andrew Hervey’s brigade suffered 150 casualties while driving the enemy from Chota-Kalra. Burra-Kalra, a small village of a few dozen houses, saw some of the most intense fighting of the Battle of Gujrat. Lt. Col. Nicholas Penny’s brigade charged through the dry nullah. They fired a volley and then rushed into the village. Ensign Sandford of the 2nd Europeans saw many enemy troops hastily leaving Burra-Kalra. “Those who remained were shot or bayoneted on the spot,” he wrote. “There was no quarter given. A number of them shut themselves up in their houses, but our men beat down the doors, and poured in volley after volley, and sullenly and savagely they died, fighting to the last.”

“The left wing, climbing up the mud walls, sprang onto the roofs of the houses, many of them letting themselves down into the narrow and torturous streets, driving the enemy out at the further side. As soon as the [Sikh] artillery outside the village saw their comrades being overpowered, they elevated their guns so as to clear the tops of the houses, notwithstanding the British and Sikh soldiers were intermixed when they struggled for the mastery,” wrote a regimental historian.

Penny took 300 casualties in taking Burra-Kalra, half from the 2nd Europeans and the rest from two Indian regiments, the 31st and 70th Bengal Native Infantry. Two Khalsa colors were captured. The enemy soldiers defended their standards to the death.

Major John Kennedy McCausland of the 70th Bengal Native Infantry had a narrow escape from death. Having been wounded, he was placed in a doolie. As the bearers took him toward the rear, a cannon ball sliced through the cloth curtain at one end and passed safely over the major to tear an exit hole in the back of the doolie.

West of the Dwala, Campbell’s division with a mix of Bengal, Bombay, and regular troops held Gough’s left. They faced Khalsa troops holding the small villages of Narawalla, Jumna, and Loonpoor. Five batteries of Company artillery cleared the villages, and Campbell’s regiments pressed forward. This enabled their batteries to get close enough to enfilade the right flank of the Khalsa’s main line. The 14th Prince of Wales’ Scinde Irregular Horse of the Bombay Army charged and drove back the Sikh cavalry.

Cavalry on the British left captured a cannon, which turned out to be one of four guns lost at Chillianwallah by Captain Alfred Huish’s troop of the Bengal Artillery. Huish was so overjoyed at the return of his cannon that he actually hugged it.

The British respected the Khalsa’s artillery. One Briton watched a Sikh gun come under the concentrated fire of several British cannons. Only two gunners were left standing, but they continued to work the gun as the British advanced closer. One of the gunners fell, but the lone survivor stayed to load and fire two rounds before abandoning the piece to the onrushing soldiers.

A group of 30 horsemen wearing Indian clothing dashed around the British right. They rode toward the headquarters detachment, intent on capturing Gough. At the time there were detachments of irregular Indian cavalry under British officers, riding about on raids and scouting expeditions. For a few anxious moments, the approaching horsemen were taken for friendly troops.

The illusion was quickly dispelled when the horsemen tried to hack their way through the headquarters guard. The raiders were variously described as either Sikhs or Afghans wearing mail. “Our men finding their swords made no impression, sheathed them, and took to their firearms,” wrote one soldier. Another soldier wrote that Gough himself drew his pistols to fire at the attackers. The headquarters escort and staff wiped out the attackers. Lieutenant H.G. Stannus of the 5th Bengal Light Cavalry, who led Gough’s bodyguard, was severely wounded in the action.

As Sher Singh’s army reeled back, Markham’s brigade entered the city of Gujrat. All over the field, the Khalsa fell back in a fighting retreat. Redcoat infantry pressed them for two miles and then halted in a new line northeast of the city of Gujrat. Company and regular British cavalry continued the chase for another 15 miles.

An estimated 2,000 of Sher Singh’s men were lost in the battle. Soldiers taken in the city of Gujrat were reported as prisoners, but few were taken alive in the pursuit of the Khalsa. The Sikhs took no prisoners at Chillianwallah. At Gujrat it was the Anglo-Indian forces who as victors slaughtered potential prisoners of war. Fifty-three artillery pieces were taken as well as most of the Sikh army’s ammunition and baggage.

Gough’s camp followers plundered the Sikh tents, which were left standing when the army abandoned Gujrat. Desperate civilians fed themselves with the meat of dead horses and bullocks, which they butchered on the battlefield.

Gough’s losses were much lower than at Chillianwallah: 92 dead and 683 wounded. Half the casualties resulted from the attacks that cleared the enemy from Burra-Kalra and Chota-Kalra. A few casualties occurred after the battle. A soldier smoking a pipe set off a supply of abandoned gunpowder, killing or wounding several men. Accidents claimed other soldiers who were assigned to blow up captured munitions.

On the day after the battle, Gilbert continued after the Khalsa. His aggressive pursuit meant that Sher Singh could not halt to reorganize and replenish their rations. The Afghans who fought at Gujrat were pursued out of the Punjab.

On March 14, 1849, Sher Singh surrendered 16,000 troops to General Gilbert at Rawalpindi. Each Sikh sepoy was given one rupee, the equivalent of two shillings, by the East India Company, and allowed to return home.

Troops were posted to watch the fords of the Chenab. Sikh cavalrymen heading for their homes were stopped and released after their weapons were taken up. Among the river guards some officers of the irregular Company cavalry expressed the wish that they might recruit some of the veterans of the Khalsa. The Sikhs would form a loyal contingent for the British when rebellion flared in India in 1857. They had little love for the British, but neither did they trust the Mughals, whom the Sikhs saw as fomenting the Great Mutiny. Approximately 20 percent of the soldiers in the Indian Army were Sikhs by World War I.

Some Sikh leaders were kept in captivity for years. The father and son at the head of the rebellion were imprisoned until 1854. Pensioned after their release, they were never allowed to return to the Punjab. Chattar Singh died in Calcutta in 1855, and Sher Singh died in Benares three years later.

Gujrat revived Gough’s prestige. Every British military post in India fired a 21-gun salute in commemoration of the victory. When General Napier arrived in India to take Gough’s place, the Second Anglo-Sikh War was already over. Gough soon retired from field service and returned to Ireland. On June 4, 1849, he was pronounced Viscount Gough by Queen Victoria.

The so-called Last Treaty of Lahore, signed on March 29, 1849, officially ended the Second Anglo-Sikh War. Ten-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh was compelled to renounce his claim to the throne, and the Punjab was annexed by the East India Company.

Duleep Singh became a prisoner. Although isolated from his mother and all Indians other than servants for many years, he nevertheless was kept in lavish style. He was exiled to England in 1854. He was treated with the respect due to his being a foreign royal. Queen Victoria became fond of the lad when he spent time with the British royal family. Awarded a substantial pension, Duleep Singh could afford to live in splendid rented mansions and travel around Europe. He was allowed just two brief visits to India before his death in 1893.

By a provision of the 1849 treaty, the magnificent Koh-i-Noor Diamond was taken by the British. Once the property of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, the diamond was acquired by Ranjit Singh in 1813. Presented by an East India Company official to Queen Victoria in 1850, the Koh-i-Noor remains part of the crown jewels of Great Britain.