By Christopher Miskimon

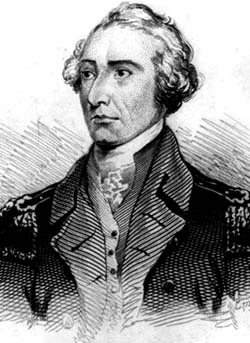

Francis Marion did not cut an impressive figure when he joined the Patriot army of Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates in July 1780. The 48-year-old officer stood slightly over five feet and weighed just 110 pounds. He had a narrow face, hooked nose, and his knees almost touched each other when he stood. “I have it from good authority that this great soldier, at his birth, was not larger than a New England lobster, and might easily have been put into a quart pot,” wrote Peter Horry, a fellow militia officer in South Carolina.

But by that time, Marion had become a well-respected military officer fighting the British during the American Revolutionary War. He was intelligent, brave, and ambitious. Although his manner could be harsh, it was largely a reflection of his unbending will. These traits, when combined with his talents as a tactician and strategist, made him a natural leader of men and gave him ample credibility with the raw militia who constituted the majority of the troops in the Patriot armies of the southern theater.

Marion was born in 1732, the same year as General George Washington, in Winyah, South Carolina. He was the youngest son of six children born to Gabriel Marion and Esther Cordes. His paternal grandparents were Benjamin and Judith Baluet Marion. Benjamin Marion was a French Huguenot who had fled France in 1690 for a new life in America free of religious persecution. When Benjamin Marion arrived, he received a 350-acre tract north of Charleston.

Marion’s father eventually discarded the occupation of a planter pursued by his father in favor of becoming a merchant. The family relocated to Georgetown, South Carolina. Unfortunately, Gabriel Marion went bankrupt, which forced his children to make their way in the world as best they could under the circumstances.

Young Francis signed on at the age of 15 as one of six crewmen aboard a merchant schooner bound for the West Indies. On the return leg of the voyage, a whale sank the schooner. He was one of only three who survived being adrift at sea for a week. The experience was sufficient to make him give up the life of a sailor. Marion eventually settled down near his brother Job along the Santee River where the long hours he spent hunting, trapping, and fishing in the region made him intimately familiar with the backwoods.

Twenty-four-year-old Marion joined the provincial militia in 1756 during the French and Indian War. Unable to defend the colony against the Cherokees, interim governor William Bull appealed to the British Army for military assistance. When British forces arrived in South Carolina, Marion noted the haughtiness of their officers.

Marion’s first exposure to war occurred in 1761 when Lt. Col. James Grant arrived in Charleston with 1,200 British regulars for a major expedition against the Cherokees. Captain William Moultrie recruited a regiment of provincial militia to supplement the British regulars, and Marion was made a first lieutenant.

Grant led his army north along the Santee and Congaree Rivers toward Cherokee country. When the army reached a defile where a previous force of regulars and militia had been ambushed, Grant chose Marion to disperse any Cherokees who were laying in ambush. Taking a group of 30 men, Marion fought a sharp action in which 21 of his men became casualties. The upshot of the June 10 skirmish was that Marion would not shrink in the face of a hazardous mission. Grant burned the Cherokee village at Echoe and carved a path of destruction through the Little Tennessee and Tuskegee Valleys. Marion learned many tactical lessons from the Cherokee War, such as the effectiveness of long-range rifles over muskets, the advantage of hit-and-run strikes, and the effectiveness of scorched-earth tactics.

In December 1774 Francis and his brother Job were elected as delegates to the First Provincial Congress of South Carolina. When the legislative body convened the following month, Marion’s brother Gabriel joined them from another parish. Despite their wealth and entrenched economic ties with England, the Marions were staunch Patriots. On April 21, 1775, Patriots in South Carolina seized weapons and ammunition from royal armories and powder magazines throughout the colony.

Marion could not resist the call to arms. The First and Second South Carolina Regiments were created on June 21. Moultrie was promoted to colonel and given command of the Second Regiment. Marion was one of the 10 captains in the regiment. He immediately embarked on a recruiting effort along the Santee, Black, and Peedee Rivers. He found 60 men keen to fight the British. He immediately began drilling his men. By September they were ready for battle.

On September 14 Marion led a detachment against Fort Johnson, which guarded the approach to Charleston Harbor. But when the Americans arrived, the British had withdrawn, leaving a detachment of five men to surrender the fort. For the next few months, the South Carolina Patriots guarded against Tory uprisings in the countryside and improved the defenses of Charleston. These preparations proved useful when the British appeared near the city in June 1776.

Lieutenant General Lord Charles Cornwallis had been preparing for an expedition to the Carolinas in Cork in the winter of 1775-1776. He embarked for the colonies aboard the flagship Bristol on February 12, 1776. The fleet was commanded by Admiral Sir Peter Parker. After a storm-tossed voyage, the fleet arrived off Cape Fear, North Carolina, on May 1. At that point, Cornwallis dispatched frigates and troop transports to Charleston. He gave command of the infantry to General Henry Clinton.

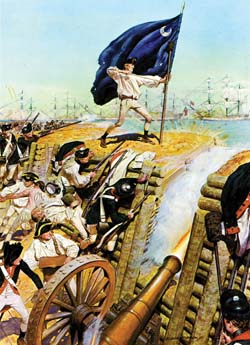

Clinton was determined to capture Sullivan’s Island at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. The Second Regiment manned a half-built fort on Sullivan’s Island with 400 men. The fort was made of palmetto logs and sand since there were no other materials available. Marion kept his men working on the defenses, and he even staged night drills to keep the men alert. Marion was rewarded for his hard work and dedication with a promotion to major on February 22, 1776.

Marion’s vigilance paid off when the British frigates attacked on June 28, 1776. The shells from the frigates had little effect because they were absorbed by the sand and soft logs that constituted the fort’s defenses. What is more, the British lost one of their frigates to American artillery fire. Marion commanded the left wing of the fort during the British amphibious assault. The stout-hearted Patriots repulsed the Redcoats. As a result, the British fleet sailed off to New York. Later that year Marion was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the Second Regiment.

The regiment spent the next two years in Charleston on garrison duty, a tedious time where Marion had to pay much attention to maintaining discipline among his bored men. In November 1778 he took full command of the regiment, albeit without promotion to colonel. The following month war returned to the southern theater.

On December 29 British Colonel Archibald Campbell led a 3,000-man force in a successful amphibious landing two miles below Savannah, Georgia. Since his troops greatly outnumbered American Maj. Gen. Robert Howe’s 850 militia force, Campbell easily captured the city.

The following summer the 15,000 Americans under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln holding Charleston were heavily reinforced by the arrival from the West Indies of 3,500 French troops under the command of Admiral Count Charles d’Estaing. The Franco-American army besieged Savannah in mid-September 1779 but received a bloody repulse in a major attack conducted on October 9. Marion’s Second Regiment participated in the ill-fated assault. As a result, the Americans retreated to Charleston.

When Marion suffered a severe injury to his ankle in early March 1780, he had to rest and recuperate. Because he did not have an active command, he was ordered to leave Charleston for the countryside. On March 29, 1780, Lt. Gen. Henry Clinton’s 10,000-strong British army invested Charleston. Lincoln, who commanded the Americans, had only 5,500 men. Following sustained bombardment, Lincoln surrendered the city on May 11 upon the advice of city officials who wanted to spare the city from the horror and destruction of an all-out assault.

The British, who were by that time focusing the bulk of their military operations against the Southern Colonies, added to their success when Cornwallis won a decisive victory over Maj. Gen. Gates’s army at Camden on August 16, 1780.

Marion was ordered to take charge of the militia along the Santee and Black Rivers north of British-occupied Charleston. He established a base on the upper Santee River from which to conduct operations. Despite the Patriots’ low fortunes, he did not hesitate to strike.

On August 23 Marion and his men drove off the guards from Murray’s Ferry. The following day he launched a bold night attack against a British outpost at an abandoned plantation that resulted in the rescue of 150 Patriot prisoners and the capture of 20 British guards. The assault was significant enough that Marion’s senior officers reported it with satisfaction to the Continental Congress. The British became concerned that South Carolina was not as pacified as they had hoped, which delayed their plan for marching north.

Marion sought to keep his command alive and do as much damage as he could. He won two more victories in his first month of campaigning. During the next few months he conducted a series of well-executed raids, skirmishes, and quick strikes. British troops and Tory militias pursued him, but he counterattacked them whenever possible.

Tragically, some pitiless leaders on both sides burned homes, hung men, and killed livestock in an attempt to punish their foe. Marion refrained from this behavior, finding it abhorrent and a punishment of the innocent, particularly women and children. He could not always stop his subordinates from doing so, but he actively discouraged it and reported occurrences to Gates, his commanding officer, in his correspondence.

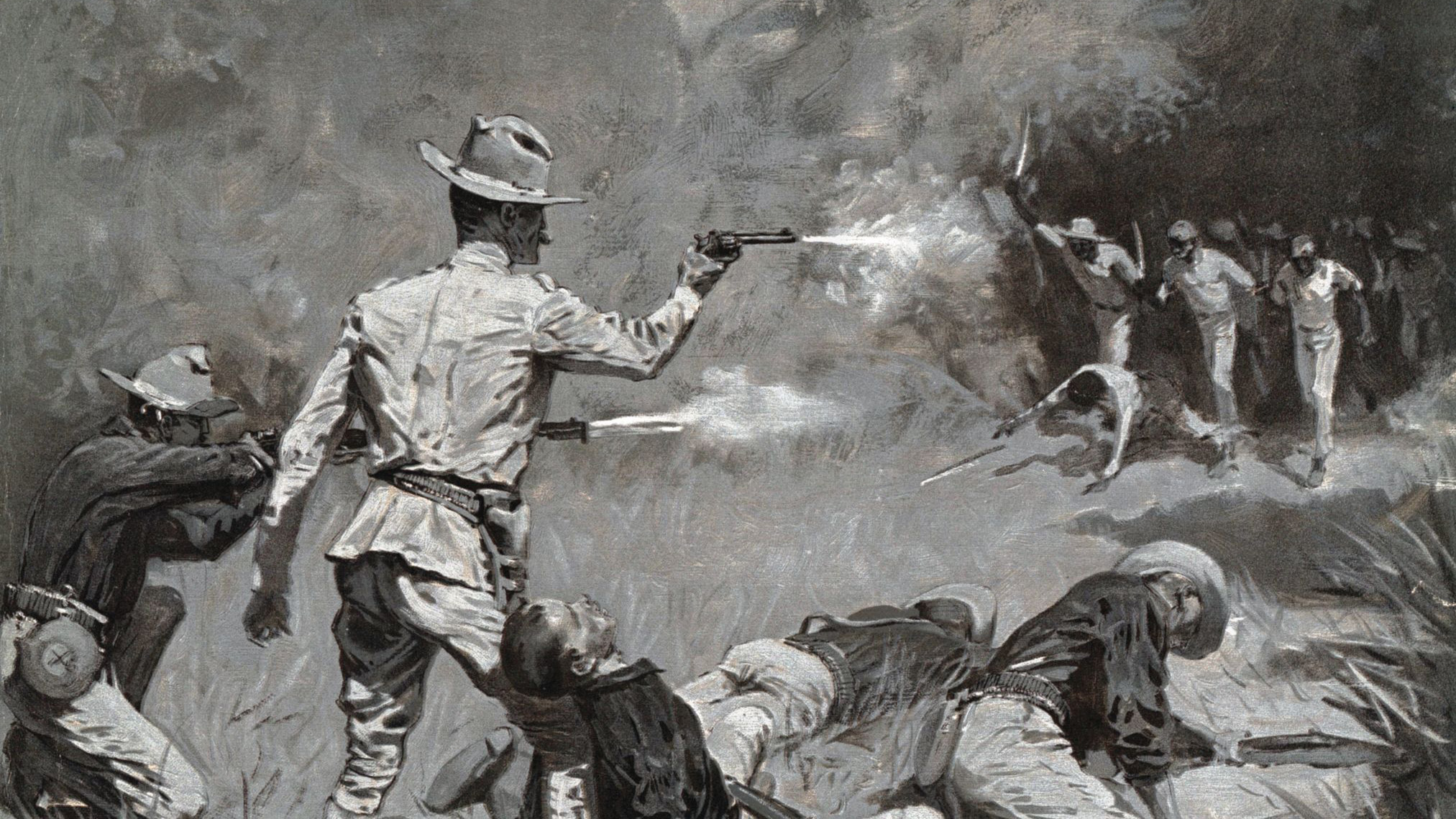

Marion’s aggressive tactics usually led to success. On September 4 at the Blue Savannah, an open sandy swale surrounded by a dense growth of scrub pines and thick underbrush, Marion’s 53-man force defeated a Tory force five times its size. The Patriots charged into the vanguard of 45 horsemen, which disrupted the main body of infantry behind it. The panicked Tories fled into the swamps.

On September 14, Marion’s Patriots routed a Tory force commanded by J. Coming Ball at Black Mingo Creek. Marion divided his command during the attack, sending it to strike both flanks of Coming’s Tory band. The routed Tories fled into the recesses of the swamp. Marion’s success compelled the irate Tories to retaliate by burning Patriot homes and plundering their farms.

The British continued to raise Tory militias to combat the Patriot groups. Marion heard of one group of 200 encamped near Tearcoat Swamp commanded by Colonel Samuel Tynes, a former Patriot who switched to the British side after the fall of Charleston. Marion, who had 150 men, launched a surprise attack on the Tories under cover of night on October 25. The confident Patriots quickly overran the sleeping Tories, inflicting 43 casualties and yet again watching as the survivors escaped into the swamp. Marion and his men confiscated the ammunition and supplies found in the enemy camp. They also rounded up 80 horses.

This string of victories frustrated Cornwallis. Eager to finish Marion quickly, Cornwallis dispatched Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton and his British Legion, a provincial unit whose troops were Tories drawn from New York and Pennsylvania. Tarleton is remembered primarily for brutal treatment of prisoners and his relentless pursuit of the enemy; however, in all fairness many leaders during this part of the war acted unduly harsh toward the enemy.

Tarleton set out after Marion with great gusto, and the two forces played a cat-and-mouse game. Each side laid ambushes for the other. Tarleton chased Marion until the tables turned and Tarleton was the one having to seek refuge in the local swamps. Tarleton eventually tired of the chase. “As for this damned old fox, the Devil himself could not catch him,” he wrote.

It was this statement that gave birth to Marion’s nickname, “Swamp Fox,” yet there is no clear evidence anyone ever called him that while he was alive. The first mention of it was in a biography published in 1809, more than a decade after his death.

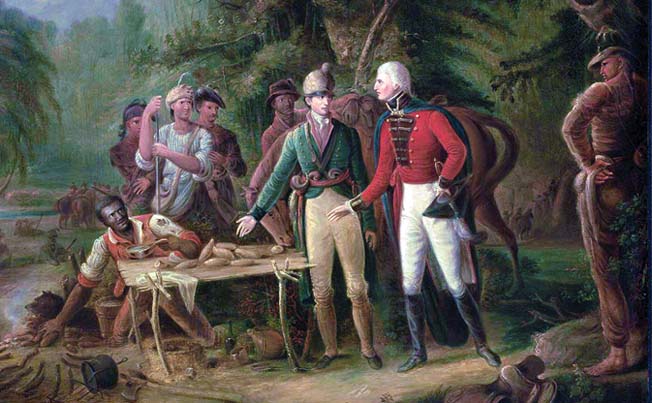

In December 1780 Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Greene replaced the incompetent Gates as commander of the Continental forces in the South. The army he inherited was small, poorly equipped, and unsuited for further action. Although Greene had to focus most of his energy on overhauling the army and preparing it for a showdown with Cornwallis, the Rhode Island Quaker took time to correspond regularly with Marion in an effort to help him as best he could. In return, Greene requested that Marion send him horses for his Continental cavalry units. Greene clearly saw the value in supporting Marion and knew that the crafty guerrilla leader was bearing the brunt of the effort against British forces in coastal South Carolina.

By January 1781 Marion was camped at Snow’s Island, running his operations from there. At times he operated with Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, the famed Continental cavalrymen, who led a legion similar to Tarleton’s. Marion and Lee enjoyed a harmonious relationship, although they had their fair share of arguments.

On January 24 they marched against the British garrison at Georgetown, a city 60 miles north of Charleston. Marion hoped to take it as this would deny the British yet another base, but as with other attempts to capture the town, this effort failed. It was a setback, but one that served to reinforce to the British the seriousness of the threat Marion posed to them.

Cornwallis dispatched Lt. Col. John Watson Tadwell-Watson to hunt down the Swamp Fox. Watson was unpopular with his fellow officers and chasing Marion was an independent command that got him away from them. He had 300 infantry, 150 Tory cavalry, and 20 dragoons along with a pair of 3-pounder cannon, something Marion’s men had never faced before. The two men met on March 8, staring at each other from horseback across a narrow causeway at Wiboo Swamp. Marion pulled his force back in an apparent retreat and the British pursued, only to discover it was a feint. The Patriots charged, but the British counterattacked with a bayonet charge supported by artillery. Marion was compelled to fall back.

This marked the beginning of a two-week running battle known as the Bridges Campaign. The culmination came at a bridge over the Black River where Marion’s riflemen took cover overlooking the bridge and a nearby ford. The bridge was wrecked and the riflemen soon took a fearful toll of the enemy. The British artillerymen could not depress their barrels sufficiently and the grapeshot went harmlessly overhead. Watson quit pursuing Marion afterward. The Swamp Fox had survived yet another attempt to eradicate him.

The next few months saw Marion conduct multiple raids against British garrisons and Tory bands. He conducted a skillful ambush at Parker’s Ferry that caused more than 100 enemy casualties at the cost of only four Patriot casualties.

Afterward, Marion’s Patriots joined Greene’s Continental army in the pitched battle fought on September 8, 1781, at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina. Greene set up his lines using the same method that the veteran campaigner, Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, had used in his decisive victory over Tarleton’s British army at Cowpens earlier in the year. This approach consisted of deploying militia in front with ranks of regulars behind them. The plan was for the militia to fire several sharp volleys before falling back through the Continental regulars stationed behind them. Marion commanded the militia line, which was composed of his troops and those from other commands throughout the Carolinas.

The 700 militiamen advanced to firing range under a sunny late summer sky. Marion’s men fired first followed by the other militia. After firing several volleys, the militiamen fired at will, shouting words of encouragement to steady each other. Most of the men averaged 17 volleys, an unprecedented number for militia. The North Carolina militia proved an exception, retreating after three volleys, but a portion of the Continental troops moved up to replace them.

The rest of the militia eventually fell back, too. At that point, the British began their methodical advance with fixed bayonets. The Redcoats ran into the second line of Maryland and Virginia Continentals who fired a sharp volley before counterattacking with bayonets. The Redcoats reeled under the counterattack. They were driven back through their camp, which the Americans seized.

Unfortunately, the American troops also seized a quantity of liquor, which some of the men proceeded to consume. The British took the opportunity to counterattack. The battle ended in a bloody stalemate. The British force held the field, but they were too weak to exploit the opportunity. Debate continues to this day over who won the battle, but Marion could boast that his brigade performed well either way.

Nevertheless, the war drew toward a conclusion with the stunning American victory on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virginia. As the conflict wound down, fighting continued in South Carolina until the British finally evacuated on December 14. Marion won his last battle at Wadboo Plantation near Charleston on August 29, 1782. Shortly afterward he returned to his plantation to await formal peace.

After the war Marion served three terms in the South Carolina Senate, served as commandant of Fort Johnson and served as a delegate to the state’s constitutional convention in 1790. Marion passed away at the age of 63 on February 27, 1795. He is revered as a hero not only in South Carolina but throughout the United States. Although reckless and at times brutal, Marion was a courageous, honorable, and passionate commander who possessed an excellent grasp of strategy and tactics. His successful guerrilla operations played an important role in the eventual victory of American forces in the southern theater.