By Nathan N. Prefer

To the Soviet military, it is known as the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation. Although it had no official name to the Japanese, it has become known in the West as Operation August Storm. It was the greatest defeat in Japanese military history, yet few outside the circles of Japanese and Soviet history are even aware that it occurred. It ensured the end of World War II as much as the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki did, yet it is often ignored in Western studies of the war.

More than one million Japanese soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians were killed or captured in a month’s bitter fighting in a far-off land that even today remains somewhat mysterious.

The seeds of the annihilation of four Japanese armies, each equal to an American field army, were planted in 1931. Japanese militarists saw the civil war in China between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Tse-tung’s Communists as an opportunity for a place at the imperialist table and a slice of the Chinese pie, and thus decided to invade China, Manchuria, and Korea.

The Imperial Japanese Army was particularly interested in showcasing its skills. They began by courting the Chinese warlord then in control of Manchuria. As the situation in China deteriorated, the Japanese Army used a series of staged provocations to eventually invade and seize Manchuria. This move, in the spring of 1931, set the stage for the Sino-Japanese War, which would last until Japan’s defeat and surrender in August 1945.

Although a giant in terms of land mass and population, China was viewed by most Japanese leaders in the 1930s and 1940s as a weak and largely defenseless area ripe for colonization and exploitation. Increasingly the Japanese militarists—primarily the Army but to a lesser extent along the coast, the Imperial Japanese Navy as well—increased their appetite for additional Chinese territory.

But these increasing violations of Chinese sovereignty brought a new player into the scenario: the Soviet Union. Premier Joseph Stalin became increasingly concerned that the Japanese were getting much too close to his own far eastern borders, and the already suspicious Russian leader began to fear their ultimate goals. This brought on the first armed clash between Russian and Japanese forces in late July 1938.

Known as the Changkufeng Incident by the Japanese and the Battle of Lake Khasan by the Russians, it would set the stage for all future conflicts between the two nations.

Essentially, a strong Russian force of about 20 infantry divisions massed on the border of Japan’s puppet state, Manchukuo—formerly Manchuria—to prevent any Japanese incursions. The Japanese, by now fully involved in the so-called “China Incident,” ignored the threat.

The Japanese had a low opinion of Russian military prowess, anyway. The Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, and the more recent Stalinist purges of his own military hierarchy, simply reinforced an already established prejudice.

When in 1938 there arose a dispute over the exact border between Manchuria, Korea, and the Soviet Union, a high-ranking Soviet defector brought much intelligence to the Japanese Kwantung Army. This defection prompted a local Soviet commander to occupy part of the disputed border line.

Even as diplomatic messages were being exchanged, the ever aggressive Kwantung Army began preparations to eject the Russian “trespassers,” and a Japanese infantry division was rushed to the area. The Russians countered, sending more troops as well. The Japanese were ready to attack and needed only the usually pro forma approval of their Emperor. But that approval did not come, infuriating the Kwantung Army leaders.

Repeated requests to begin the battle were denied, only to be followed by more urgent demands. Finally, the local Japanese division commander launched an attack on his own, claiming that the Russians were digging defensive positions within Japanese territory.

It was not the first, nor would it be the last time that the Kwantung Army started a war all on its own. Indeed, during this crisis the leaders of the Kwantung Army seriously discussed prospects of bringing down the current Japanese government should it interfere with their operations.

The Changkufeng battle was comparatively small. Fewer than 2,000 Japanese soldiers attacked in darkness and with surprise, overwhelming the Soviet defenders. The Japanese believed the issue settled. Not so the Russians.

General Grigori Shtern brought up his 49th Corps of the Red Banner Far Eastern Army, and repeated Soviet counterattacks drove the Japanese back, with heavy casualties on both sides. Diplomacy eventually settled the dispute, but the Japanese were unpleasantly surprised by the force and volume of the Russian military response. The result was a change of plans by the Kwantung Army regarding a possible invasion of eastern Russia. To prevent further Russian action, the Japanese ordered a more aggressive border security policy for all their units.

This policy resulted in the next incident, commonly known as the Nomonhan Incident. Repeated clashes between border-guard units finally erupted into open warfare on May 11, 1939. The Nomonhan Incident was much more like a full-scale war than Changkufeng.

Stalin decided that he had had enough of Japanese provocations. He ordered a heavy response and sent a new up-and-coming military leader, Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov (who would later distinguish himself at the Battles of Moscow, Stalingrad, and Berlin), to take command.

The resulting battles, which lasted into August 1939, cost the Japanese between 18,000 and 23,000 casualties and achieved nothing in terms of additional territory. Once again diplomacy resolved the issue but left the pot simmering. In April 1941, to cool the pot, a nonaggression pact was signed between the Soviet Union and Japan.

Within a year of the Nomonhan Incident, Japan’s leaders were trying to decide how to finally knock out China and end a war that seemed interminable. One choice was to attack the Soviet Union, thereby eliminating the northern threat and freeing up forces for the war in China.

Others argued for a strike to cut off all avenues of resources to China, starving her into submission. This, other voices said, might touch off a war with the United States, Great Britain, and Holland.

Already in the spring of 1940, German forces had overrun much of Western Europe and had pushed the British Expeditionary Force out of Dunkirk and back to Britain. In September 1940, Japan allied herself with Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany by signing the Tripartite Pact.

These seemingly easy successes in Europe whetted the Japanese leaders’ appetite for an aggressive strike against their perceived Western foes. The results, of course, were the 1941 attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Wake Island, and other American, British, French, and Dutch territories in the Pacific.

Between 1940 and 1945, the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria, which also had responsibility for Korea, remained relatively static. There were no significant incidents and no struggles with the Russians. But the Army itself was being bled by the needs of the Imperial Japanese Army rampaging across the Pacific. Several of the best combat divisions within the Army were called up to do battle in New Guinea, the Philippines, and the Central Pacific. This left the Kwantung Army with inadequately trained and equipped forces should any enemy suddenly appear.

That enemy indeed appeared as a result of the several Allied political leaders’ meetings during the course of the war. As the war rolled on, both the Americans and British were fully engaged in battle in North Africa, Italy, northwestern Europe, and the Pacific. (The British, after their early losses, had, relatively speaking, only token forces left in the Pacific.) The Western Allies, therefore, were anxious for some assistance in defeating Japan once Germany surrendered. Plans had to be made.

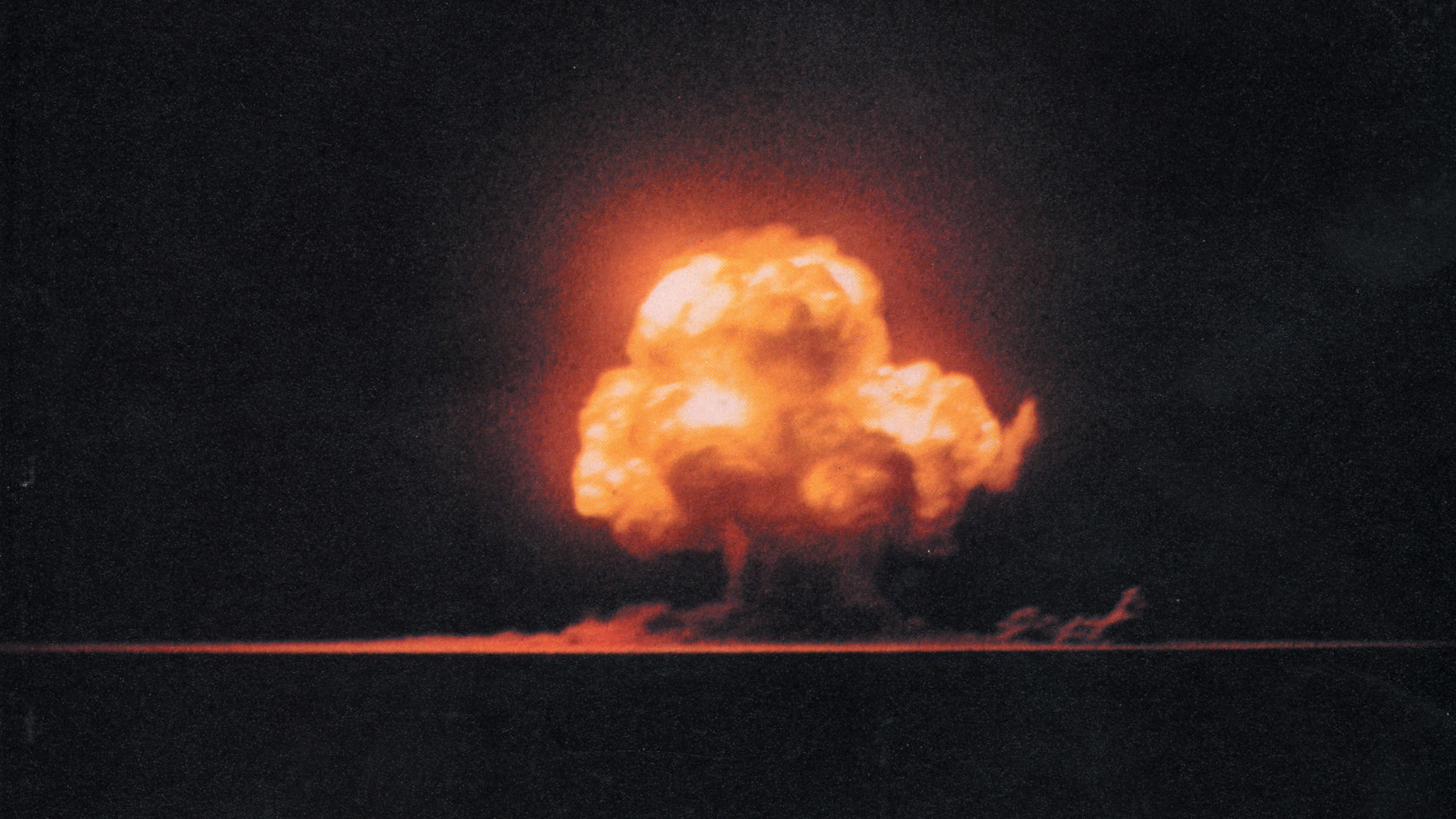

The joint U.S.-British effort to develop an atomic bomb was a well-kept secret, and there was no proof that it would work. Even if it did, it might not force Japan’s surrender without a full-scale invasion of the Home Islands. Many requests—at Tehran, Yalta, and most recently at Potsdam—had been made for Russia to enter the war against Japan.

Stalin had agreed in principle but had put off releasing any details. But, as the war continued and his spies in the British and American intelligence communities reported progress on the atomic bombs, Stalin became more interested in acquiring territory in the Far East before the war ended.

As a result, he agreed to declare war on Japan within three months after Germany surrendered. Originally planned for August 15, 1945, the Russian declaration was moved up when the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

In mid-1945, the Kwantung Army contained 24 infantry divisions, two tank divisions, five air squadrons, and totaled 780,000 officers and men. In addition, seven more infantry divisions with 260,000 personnel were in Korea and subject to joint operations.

The Kwantung Army commander was General Otozo (Ichikawa) Yamada, with headquarters located at Hsingking. Under his command were the First, Third, and Fifth Area Armies, with numerous independent units.

In addition, General Yamada had under his command armies of the puppet states of Manchukuo and Mengjiang, with 220,000 and 10,000 troops, respectively. Some sources have said that available Japanese defense forces totaled 1,100,000 officers and men.

There were also tens of thousands of Japanese civilians, men, women, and children, who had settled in Manchuria as colonists or worked for the Imperial Japanese Army.

Even as the Russians were about to battle for Berlin in April 1945, arrangements were made to release some major Red Army combat units for the coming war with Japan in the Far East. Beginning in March 1945, Stalin began transferring forces to the East, including the Karelian Front and the 2nd Ukrainian Front. (A Front was the Soviet equivalent of a U.S. Army Group and generally consisted of three to five armies—more than 100,000 men.)

These brought with them four army headquarters: the 5th, 39th, and 53rd Infantry and 6th Guards Tank Armies. These had not been chosen at random. Rather, each had some combat experience that would be needed in Manchuria. Some had fought in marshes and swampy terrain, while others had fought in the Carpathian Mountains—another feature they would face in Manchuria’s Grand Khingan Mountains.

In addition, a host of artillery, engineer, and tank regiments were also shipped east to reinforce the larger armies. Beginning in March and continuing through August 1945, some 20 to 30 trains per day were rolling east on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, carrying these and other reinforcements for the Far Eastern Army.

By August, Soviet strength in the Far East had doubled, from the former 40 divisions to 80 divisions with strong supporting forces. These troops were assembled in rear areas well out of view of the Japanese border guards, and as the time for the attack neared they were quietly moved forward under cover of darkness to their assault positions (much as Nazi Germany did prior to its 1941 sneak attack against the Soviet Union).

Manchuria itself covered 1.5 million square kilometers and encompassed mountain ranges, swamps, fertile valleys, and barren stretches. Its strategic importance stemmed from its geographic location, bordered on the south by Korea, on the east and north by the Soviet Far Eastern provinces, including Siberia, and on the west by Outer Mongolia.

Japan, China, and the Soviet Union had all viewed this area as a critical location for either defense or aggression against their neighbors, should that become necessary. But the area had a poor road network, and those roads were subject to deterioration under adverse weather conditions.

The key area to controlling Manchuria was its Central Valley region, where most of the population lived and where much of its agricultural production originated. Other key areas included the Barga Plateau and the Grand Khingan Mountains, which controlled, militarily speaking, the rest of the country.

The Japanese defenders consisted of two area armies, the rough equivalent of an American army group. The 1st Area Army, under the command of General Kita Seiichi, included the 3rd Army and the 5th Army, each with three infantry divisions.

Under Seiichi’s direct command at 1st Area Army were four more infantry divisions and one independent mixed brigade. Responsible for eastern Manchuria, the 1st Area Army counted 222,157 soldiers within its ranks by August 1945.

General Ushiroku Jun’s 3rd Area Army was the other major defending force in Manchuria. It included the 30th Army with four infantry divisions, one independent mixed brigade, and one tank brigade, as well as the 44th Army with three infantry divisions, one independent mixed brigade, and one tank brigade.

Under Jun’s control at 3rd Area Army were an additional infantry division and two independent mixed brigades. Responsible for central and western Manchuria, Jun had 180,971 men under his command.

A third force, Lt. Gen. Uemura Mikio’s 4th Separate Army, covered north-central and northwest Manchuria with three infantry divisions and four independent mixed brigades amounting to 95,464 soldiers. In reserve under direct Kwantung Army control was the 125th Infantry Division.

After hostilities with the Soviets began, Imperial Japanese Headquarters in Tokyo assigned to General Yamada the 34th Army, headquartered at Hamhung in northern Korea, with the 59th Infantry Division at Hamhung and the 137th Infantry Division at Chongpyong—a total of 50,104 additional troops.

The 17th Army in southern Korea, with another seven infantry divisions and two independent mixed brigades, was also assigned at this time. The Sungarian Naval Flotilla—a collection of small coastal supporting naval craft—was also a part of the defense.

In Manchuria alone, the Imperial Japanese Army mustered 713,724 soldiers, 1,155 tanks, 5,360 artillery pieces, and about 1,800 aircraft. The average Japanese infantry divisions had more men (about 12-16,000 troops) than the average Soviet division (with perhaps 10-12,000 troops).

Overall, the Kwantung Army seemed to be a formidable force with 31 infantry divisions, nine independent mixed brigades, two tank brigades, and one special-purpose brigade. But these figures were deceiving. Japanese armor was inferior to anything the Soviets possessed, even though the Russians were using, in some units, tanks that had been obsolete on the Western Front by 1941.

The Soviets also were masters in the use of artillery and outnumbered the Japanese in Manchuria nearly five-to-one in both tanks and artillery. In the air, the Japanese were outnumbered two to one. In manpower, the approaching Soviet juggernaut would be closer to equal, but even here the Japanese were about to be outnumbered more than two to one in numbers of troops.

The Japanese had adjusted their planning as time went by and the world’s circumstances changed with the developing war situation. Before 1944, the Japanese continued to plan for an aggressive attack against the Chinese and Soviets to advance their territorial goals in the Far East. By September 1944, those plans had changed to a strong defense of Manchuria at the borders.

Those plans were again changed to a defense-in-depth, with the borders lightly defended and the main Japanese resistance to be set at selected fortified locales within Manchuria and a final stand to be made in the Tunghua stronghold just above the Korea/China border.

Imperial General Headquarters ordered that the many border garrisons be combined and formed into eight new infantry divisions, numbered 121 through 128, plus four mixed brigades. These were to replace four regular divisions transferred to the Home Islands, the Philippines, and Central Pacific.

Headquarters in Tokyo also decreed that some 250,000 Japanese Army reservists be called up for the Kwantung Army. These would be organized into eight more divisions, numbered 134 through 139 and 148 and 149. Seven more brigades and supporting units were also to come out of the reservist callup.

But these measures actually weakened the Kwantung Army, replacing veteran troops with new troops in units that were badly in need of combat training.

The latest plans called for platoons and battalions to be left at the borders to delay the enemy while the main forces withdrew 40 to 70 kilometers to the fortified localities, which were each to be defended by one or more divisions.

The withdrawal was to be as slow and deliberate as possible and directed finally on the prepared defenses at Tunghua and Antu in a decisive defensive battle along the northern Korean border. About one-third of the Japanese forces were to defend the border while the remaining two-thirds were to withdraw into the fortified redoubts.

Japanese intelligence and Japanese diplomatic couriers using the Trans-Siberian Railway had reported seeing massive troop and equipment movements from west to east and noted the unusual recall of Soviet diplomats and their dependents from Japan.

An attack by the Soviet Union had been long expected, but it had been hoped that the Russians would, as one historian put it, “adopt a policy of ‘waiting for the ripe persimmon to fall,’ rather than shaking the tree and were expecting nothing before the end of August.”

This was even though, in April 1945, the Soviets had told the Japanese that they would not be extending their nonaggression pact, which still had a year to run.

The Russians were indeed preparing a strong attacking force to overcome the Japanese plans and forces. The senior command was the Far East Theater Headquarters, headed by Marshal of the Soviet Union Alexsandr Mikailovich Vasilevsky.

After joining the Red Army and becoming a company commander in 1918, Vasilevsky became a battalion commander. By 1936, he was attending the General Staff Academy, after which he was posted to the Soviet General Staff. He was in the operations division of the Soviet General Staff in 1940 and, within two years, was the chief of staff.

As Stalin’s personal representative, he participated in the Stalingrad, Kursk, and Belorussian operations before taking command of the 3rd Belorussian Front in East Prussia in 1945. That same year he was designated to command the Soviet Forces, Far East.

The first of Marshal Valislevsky’s operational armies was known as the Trans-Baikal Front. This army had under its command the 6th Guards Tank Army, the 17th, 36th, 39th, and 53rd Armies, and a Mongolian Cavalry-Mechanized Group, along with the 12th Air Army.

Its 640,040 men were divided into 30 rifle divisions, five cavalry divisions, two tank divisions, 10 tank brigades, and eight mechanized brigades; some 41 percent of the Soviet forces were within this group. Commanding the Trans-Baikal Front was Marshal of the Soviet Union Radion Yakovlevich Malinovsky, who had previously commanded a front in the Battles of Odessa, Budapest, and Vienna.

Malinovsky’s compatriot was 48-year-old Marshal of the Soviet Union Kirill Meretskov and his 1st Far Eastern Army, with the 5th Guards Army, 1st Red Banner Army, 25th and 35th Armies, 10th Mechanized Corps, and Chuguevsk Operational Group, supported by the 9th Air Army.

In total, Marshal Meretskov had 586,589 troops in 31 rifle divisions, one cavalry division, 12 tank brigades, and two mechanized brigades. Meretskov’s forces represented 37 percent of the total Soviet force.

The smallest of these combined Soviet armies was the 2nd Far Eastern Front with the 15th, 16th, and 2nd Red Banner Armies, 5th Separate Rifle Corps, and the Kuriles Operational Group, supported by the 10th Air Army. With 337,096 men, it represented only 21 percent of the total Soviet force in the East of 1.5 million men.

These combined armies were the result of the constant Soviet effort at updating and modernizing their forces as they learned from experience. A combined arms Soviet army at this stage of the war consisted of between 80-100,000 soldiers divided into 7 to 12 rifle divisions, one or two artillery brigades, a tank destroyer brigade, an antiaircraft brigade, a mortar regiment, signal regiment, engineer regiment, two or three tank brigades, and a tank or mechanized corps. These troops were armed with 320 to 460 tanks, 1,900-2,500 guns and mortars, and 100 to 200 self-propelled guns.

Soviet tactics against enemy defenses had also been articulated into military regulations. Superiority over the enemy forces on one particular axis needed to be achieved, then close tank-infantry cooperation, strongly supported by artillery and air power, would attack.

Mobile groups of tanks and mechanized troops would break through, creating an initial penetration at which time the entire attacking force would follow through and exploit that penetration, breaking up the remaining enemy defenders into smaller groups that were then defeated in detail. Meanwhile, airborne, reconnaissance, and partisan groups would disrupt the enemy’s rear areas, cutting lines of communication and supply.

For the Manchurian campaign, 50-year-old Marshal Vasilevsky planned a double envelopment of the Kwantung Army, attacking along three separate axes of advance. His objective was to destroy the Kwantung Army and secure the entire Manchurian territory for the Soviet Union as quickly as possible, before the end of the war halted all military operations.

To do this he had planned to launch Marshal Malinovsky’s army first, followed in a day or two by Marshal Meretskov’s, but on August 7—the day after the Americans dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima—Vasilevsky changed his mind and decided on a two-pronged simultaneous attack using all three armies.

On August 9, a second A-bomb wiped out Nagasaki. Still, the Japanese did not surrender.

On that same day, Vasilevsky directed the Trans-Baikal Front to strike east into western Manchuria while the 1st Far Eastern Front attacked west into eastern Manchuria. These attacks were to clear the Japanese out of Manchuria and to join with each other in the Mukden, Harbin, and Kirin areas of south central Manchuria.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Far Eastern Front would launch a supporting attack into northern Manchuria and also join with the others in the Harbin and Tsitsihan areas of Manchuria. Attacks planned against southern Sakhalin Island and the Kurile Islands would be delayed, depending upon the speed of the other operations.

The primary thrust was to be made by the Trans-Baikal Front, striking 350 kilometers into the Japanese-held interior by the 10th to 15th day of the attack. Led by Col. Gen. A.G. Kravchenko’s 6th Guards Tank Army with Lt. Gen. A.I. Danilov’s 17th and Col. Gen. I.I. Lyudnikov’s 39th Armies alongside, the object was to bypass the fortified regions around Halung-arsheen and advance upon Changchun.

The attack was designed to destroy the Japanese border defenders, cross the Grand Khingan Mountains, and occupy the central Manchurian Plain between Lupei and Solun as soon as possible.

According to the Soviet timetable, the 6th Guards Army would have to cross the deserts of Inner Mongolia, secure the passes through the Grand Khingan Mountains, and occupy Lupei by day five of the offensive. Subsidiary attacks by the Soviet-Mongolian Cavalry-Mechanized Corps would also cross the desert and strike for Kalgan. Lt. Gen. A.A. Luchinsky’s 39th Army was to cross the Argun River, secure Hailar, and prevent Japanese troop withdrawals through the Grand Khingan Mountains.

The 1st Far Eastern Army was to penetrate the Japanese border defenses or bypass them, after which they were to operate in the rear of the enemy forces in the fortified zones. Col. Gen. A.P. Beloborodov’s 1st Red Banner Army and Col. Gen. N.I. Krylov’s 5th Army, with the 10th Mechanized Corps, were to attack from northwest of Vladivostok toward Harbin and link up there with the Trans-Baikal Front, surrounding many Japanese main force units. They were to also secure Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula.

General M.A. Purkayev’s 2nd Far Eastern Front was to attack on a broad front across the Amur and Ussuri Rivers to keep maximum pressure on the Japanese and destroy those facing them. They were to also prevent a withdrawal of any enemy forces attempting to reinforce other Japanese forces.

General M.F. Terëkhin’s 2nd Red Banner Army was to attack toward Tsitsihar after crossing the Amur River. The 5th Separate Rifle Corps was to attack toward Bikin and secure Paoching, then move to Poli, where it was to link up with the 1st Far Eastern Front.

The Soviet plans called for speed, surprise, and mobility. Tanks would lead all attacks, closely supported by infantry, artillery, and air support. The objective was to prevent the enemy from bringing reinforcements from North China or Korea and then to destroy the Kwantung Army. The attack in all sectors was designed to tie down all the Japanese defenders so that no one area could reinforce another.

At two minutes after midnight on August 9, 1945, after a quick declaration of war against Japan, Soviet forces crossed the border. Advance units crossed both the Inner Mongolia and Manchuria borders, leading main force units behind them.

Initially, only Luchinsky’s 36th Army faced any resistance when that army’s routes passed through fortified Japanese border areas—most other advances were unopposed, a result of the most recent Japanese plans to withdraw into fortified localities.

On the right flank of the Trans-Baikal Front, Pliyev’s Soviet-Manchurian Cavalry-Mechanized Corps advanced with the 25th Mechanized Brigade and 43rd Separate Tank Brigade leading two columns forward. They swiftly advanced across the desert of Inner Mongolia, covering 55 miles on the first day.

To their east, Danilov’s 17th Army, led by the 70th and 82nd Tank Battalions, also entered Inner Mongolia unopposed; these columns moved 70 kilometers the first day. The spearhead of the Trans-Baikal Front—Kravchenko’s 6th Guards Tank Army—advanced into Inner Mongolia in two columns, each broken down further into multiple columns, stretching over an advancing front line some 20 kilometers wide.

The forward detachments usually consisted of a rifle regiment, a tank regiment, and an artillery battalion. Opposition was limited and progress remained rapid. By dark the forward elements were in the foothills of the critical Grand Khingan Mountains.

On Kravchenko’s right flank, Lyudnikov’s 39th Army attacked on a southern axis against the Japanese 107th Division. The Wuchakou fortified region was bypassed and, led forward by the 61st Tank Division, the 39th Army continued south, passing the 1939 battlefield of Nomohan (Khalkhin-Gol) to join the 94th Rifle Corps, whose two divisions were attacking the Hailar Fortified Region in support of the 36th Army. Small Japanese counterattacks, supported by Manchurian cavalry, were easily beaten off.

But in some cases, the terrain—more than the Japanese—slowed the Soviet advance. To keep the forward momentum going, many commanders organized new forward detachments built around self-propelled artillery battalions. With infantry and tanks along, these could move faster and farther than previous organizations.

The attackers continued to either overrun or obliterate Japanese defenses and their occupants. The 5th Army, with 12 divisions and 692 armored vehicles, overran the Japanese 124th Division by advancing quickly and penetrating the border at areas the Japanese had deemed impassible, moving swiftly and attacking unexpectedly.

On the left flank of the Trans-Baikal Front, General Luchinsky’s 36th Army sent two rifle regiments of the 2nd Rifle Corps across the swollen Argun River using amphibious vehicles. Lt. Gen. Mikio’s Fourth Separate (Japanese) Army defended Hailar with the 80th Independent Mixed Brigade and 119th Division, also supported by Manchurian Cavalry. These Japanese units were installed in the Hailar Fortified Region.

Undeterred, the Soviet 205th Tank Brigade managed to secure the bridges north of Hailar under cover of rain and fog before being ordered to conduct a night attack on the city. Supported by the 94th Rifle Division, the attack managed to surround the city by the next day, August 10.

Although the Soviets secured the outskirts of the town, the 80th Independent Mixed Brigade managed to hold the city center while the 119th Division withdrew to secure the passes through the Grand Khingan Mountains. Heavy fighting would continue in several areas such as these until after the official surrender.

The Japanese had expected a Soviet offensive into Manchuria but believed that it could not begin before autumn. The August 9 assault not only surprised them, but also caught them in the process of reorganizing their defenses and units. The result was a massive victory by the Soviets, despite fierce and dedicated resistance by many Japanese units.

Confusion quickly grew within Japanese ranks. General Ushiroku, commanding the 3rd Area Army, decided to withdraw his forces to defend Mukden, where most of his soldiers’ families resided. This was contrary to General Yamada’s plans and, of course, further disrupted the Japanese defensive scheme.

The Soviet advance continued to suffer from terrain and logistical problems, which caused more concern than Japanese resistance. In the 6th Guards Tank Army, for example, General Kravehenko had to replace one of his leading elements, the 9th Guards Mechanized Corps, because many of its tracked vehicles, including Lend-Lease American Sherman tanks, had broken down or were out of fuel.

Kravehenko moved up the 5th Guards Tank Corps on August 10 to lead his advance; the tracked vehicles handled the rough terrain better than his wheeled vehicles. This enabled him to cross the Grand Khingan Mountains with the 7th Guards Mechanized Corps using two roads and crossing at Mokotan on August 10-11. The 5th Guards Tank Corps, followed by the 9th Guards Mechanized Corps, crossed at Yukoto over one road at the same time.

The 5th Guards Tank Corps reached the high point in the mountains at 11 pm, August 10, and then moved rapidly downhill in the dark and rain, crossing the entire mountain range in just seven hours after covering 40 kilometers. The other corps, encumbered with wheeled vehicles, took longer but nevertheless made the crossing in good time.

By daylight on August 10, the 6th Guards Army had reached the central Manchurian plain; the followup units arrived the next day, August 11. Immediately they moved east to continue the advance.

The 5th Guards Tank Corps reached Lupei on August 11, and the 7th Guards Mechanized Corps seized Tuchuan on the 12th. The operation, planned for five days, had lasted barely four days. There had been no opposition to speak of; Japanese units had already begun to withdraw.

August 12 saw the first serious resistance by the Japanese 107th Division near Wuchakou. The Soviet attack dispersed the defenders, who lost considerably in arms and equipment.

That same day, the 221st Rifle Division accepted the surrender of General Houlin, commanding the Manchurian 10th Military District, along with more than 1,000 of his men. But the fight for Hailar continued unabated.

The Soviet command redeployed its forces, releasing the tanks and replacing them with more infantry. Eventually the Japanese of the 80th Independent Mixed Brigade were driven out of Hailar itself but took up positions overlooking the city and continued to deny it to the Red Army.

Similarly, the 94th and 393rd Rifle Divisions had their hands full with the Japanese 119th Division, still blocking certain access routes to the nearby Grand Khingan Mountains.

General Pliyev’s Soviet-Manchurian Cavalry-Mechanized Corps also had problems, crossing the Mongolian deserts opposed by Manchurian and Mongolian cavalry units—a civil war in miniature. Nevertheless, they pushed their way forward and seized Taopanshin in four days of fighting.

Another problem that gave the Soviets as much trouble as the Japanese was a fuel shortage. The 6th Guards Tank Army, leading the advance of the Trans-Baikal Front, had to stand down for two days, August 12-13, due to lack of fuel, which stemmed from logistical difficulties. The leading forces had advanced so far and so fast that the logistical tail could not keep up over the miserable roads in the area.

To address this issue, vehicles—including Sherman tanks, which used more fuel than the standard Russian tanks—were dropped out of the advance; the 453rd Aviation Battalion of the Red Air Force was used to fly gasoline and other fuels to the forward areas. Japanese kamikaze attacks on Russian supply lines contributed to the shortages.

Yet savage fighting continued. At the Wunoerh railroad station, the 275th Rifle Division spent August 13 and 14 eliminating a strong Japanese defensive position, while the 2nd Rifle Corps still fought for Hailar against the 119th Division. While all this continued, the Japanese government was trying to find a way out of the war.

On August 14, the Japanese government contacted the Allied powers for a clarification of surrender terms published earlier. In the interim, the Japanese Emperor ordered his forces to cease fire on August 14 pending further instructions.

Not unexpectedly, General Yamada countermanded the Emperor’s order, causing great consternation in his own ranks. The Japanese soldier had sworn an oath to his Emperor, which required unquestioning obedience, but it also required a no-surrender conviction.

Many Japanese were torn between obedience to the Emperor and obedience to the oath requiring no surrender. This confusion not only created factions within the Kwantung Army but further weakened its defensive efforts. Finally, on August 19, General Yamada agreed to a cease-fire.

Now it was Marshal Vasilevsky’s turn to ignore the cease-fire. Anxious to overcome Japanese resistance and uncertain if the cease-fire would result in a surrender—plus a desire to seize as much ground as he could before any such surrender—Vasilevsky continued with his offensive. Orders were issued for the capture of Mukden, Tsitsihar, and several other significant Manchurian cities.

On that same day, August 15, the Soviet-Manchurian Cavalry-Mechanized Corps ran into stiff opposition from the Inner Mongolian 3rd, 5th, and 7th Cavalry Divisions at Karibao. But two days of fierce fighting culminated in the surrender of the Mongolians and the capture of 1,635 prisoners of war.

When the Russians seized Harbin in central Manchuria they uncovered one of the most infamous war crimes of the century. There a Japanese doctor, Shiro Ishii, had created the top secret Unit 731. Here Japanese doctors and others tried to create new biological warfare weapons using human guinea pigs—mostly Chinese civilians and POWs, but also British and American POWs.

Hidden under the guise of a lumber mill, thousands of human beings were experimented upon, including live vivisections and injections of various diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis, typhoid, botulism, and a host of other deadly viruses. Like the Germans, the Japanese disposed of the bodies in a crematorium.

The Russians would later try as war criminals the Japanese staff they captured at Harbin, but those who escaped to Japan and were seized by the Americans, including Doctor Ishii, were never placed on trial.

Meanwhile, Tokyo continued in turmoil. The Emperor’s decision to surrender had been contested by many of his advisors, including the Imperial General Headquarters hierarchy and many junior officers who threatened violence against leading government officials if the war was not continued.

Even the second atomic bomb had not dissuaded them from continuing the war. But when reports from the Kwantung Army began to arrive, reporting significant Soviet penetration in Manchuria and the situation as “obscure,” objections to surrender were far less convincing.

Finally, on August 18, Japan officially announced the surrender of the Kwantung Army. On that same day, the Soviet-Manchurian Cavalry-Mechanized Corps symbolically crossed the Great Wall of China and marched toward Peking (today Beijing), joining en route the Chinese Communist 8th Route Army.

On this day as well, Hailar finally fell, producing 3,227 prisoners of war. Mukden was occupied on August 24, and on the 30th the last major Japanese force, the 107th Division, surrendered to the 94th Rifle Corps, which was mopping up rear areas. Another 7,858 POWs were sent to the prison camps.

Although such figures are suspect and have been repeatedly altered by the respective governments since their first publication, the Russians claimed the Japanese suffered 84,000 killed and 594,000 captured. Their own losses, since updated, are given as 12,103 killed and 24,550 wounded.

But these figures ignore the casualties of the Manchurian and Mongolian auxiliaries, as well as the undoubted thousands of Japanese reservists and civilians killed during the campaign.

Further, what is left out of these figures are the missing. Of the 2,726,000 Japanese nationals, two-thirds of whom were civilians, captured during the Manchurian Campaign, 254,000 died in Soviet captivity and a further 93,000 were listed as missing, fate unknown.

One Japanese estimate indicates that as many as 376,000 died or went missing in the first winter in captivity. Another source states that of 220,000 Japanese civilian settlers, 80,000 died, either having starved to death, committed suicide, or been killed by Chinese partisans. Only 140,000 survivors returned to Japan.

As had happened when the Red Army overran Germany, tens of thousands of Japanese—and Chinese—women were raped, many repeatedly, as the Soviets completed their conquest of Manchuria.

At one airfield where Japanese women had collected for safety, one later recorded, “Every day Russian soldiers would come in and take about 10 girls. The women came back in the morning. Some women committed suicide. The Russian soldiers told us that if no women came out, the whole hangar would be burnt to the ground, with all of us inside.”

The Soviets’ Manchurian Campaign, August Storm, destroyed the last vestige of Japanese military power outside Japan, and put the final nail in the coffin of those Japanese militarists who, even after suffering two atomic attacks, intended to continue the war to the death.

Only the most fanatical Japanese still wanted to continue what had become a war of annihilation. These few were either killed by the rational Japanese leaders or conveniently committed suicide. The Soviet invasion of Manchuria—which led to Japan’s greatest defeat—had helped to end the Pacific War.