By Joseph M. Horodyski

During the dark daysof December 1941, when it seemed as if American and British bases were falling like dominoes across the Pacific, two incidents during the Japanese attack on the naval base at Pearl Harbor gave American morale a much needed boost.

One of these occurred when Army Air Corps lieutenants George Welch and Ken Taylor managed to get airborne in their two Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters from their base at Haleiwa Field and between them downed five enemy aircraft that Sunday morning, ending their attacks only when their ammunition and fuel were exhausted. But their exploits were not fully known until after the attack was over, they had been debriefed and their claims verified, and their story appeared in newspapers to a country hungry for positive war news. They achieved their exploits in the open skies over Hawaii, mostly unseen by those on the ground below.

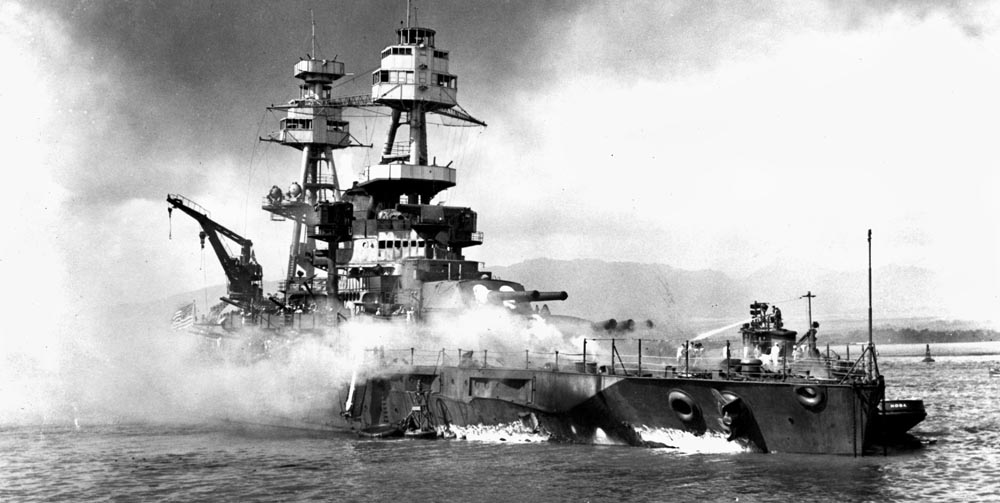

The second incident was more widely witnessed. The World War I-vintage battleship USS Nevada was the only capital ship that day that managed to get underway during the attack and attempt an escape from the confining waters of Pearl Harbor to the open sea; battered and heavily damaged, her captain chose to beach her on a nearby spit of land so she could be repaired and readied to fight another day. Though her run for the sea lasted barely 30 minutes, it was later claimed (rightfully or not) to have been witnessed, at least in part, by just about every serviceman present that Sunday at Pearl Harbor from numerous vantage points. It was photographed while it was happening and gave an immediate lift to the spirits of those resisting the Japanese onslaught. Because of the vast number of witnesses, the story of her dash to the sea began to spread, either by word of mouth or telephone, almost immediately after the attack. Yet her name is little known today by the general public, and the story of how she became the only ship that day to nearly escape the Japanese attack is even less known.

The USS Nevada was launched on July 11, 1914. As the lead ship of her class she boasted what were then three new features that later became standard among U.S. ships: three turrets with three guns each; oil fuel rather than coal; and heavy armor plating to protect her vital machinery spaces rather than lighter armor spread over the entire ship. In the parlance of the day she was known as a “super dreadnought.”

At 583 feet long, she boasted 14-inch guns as main weaponry, achieved a speed of 20 knots, held a crew of 1,500 men, and displaced some 30,000 tons. Her World War I career was brief, mostly consisting of Atlantic convoy duty. After the war she served in the Atlantic Fleet until 1930, representing the United States at the Peruvian Centennial Exposition in July 1921.

In 1930, she was modernized with the replacement of her “basket” masts for tripod masts, a reduction in her secondary 5-inch armament, a new superstructure, new steam turbines, two new catapults for her three spotter aircraft, and eight new 5-inch antiaircraft guns. At the conclusion of this overhaul, she joined the Pacific Fleet where she remained for the next 11 years.

On December 7, 1941, the Nevada and her sister ships were spending their first weekend in port in more than five months. Vice Admiral William Halsey had been given the task of reinforcing Wake Island’s Marine detachment with additional fighter aircraft. Halsey refused to take the slower battleships with him to try and keep up with his 30-knot fleet of aircraft carriers, and so they were resting at berth that Sunday morning instead of being out on patrol. Nevada’s position was on Battleship Row alongside Ford Island in the center of the harbor, immediately behind the USS Arizona, soon to become famous in her own right. But, unlike other battleships moored nearby that day Nevada was not paired next to an adjacent battleship and so was free to maneuver when the attack began.

At 0600 hours Lieutenant Lawrence Ruff, Nevada’s senior communications officer, rose from his bunk. He had opted to turn in early following the ship’s movie the previous evening. He had volunteered to escort the ship’s chaplain, Father Drinnan, in a motor launch over to the hospital ship USS Solace, where Father Drinnan was scheduled to hear confessions and perform Sunday morning services. Upon his transfer to the Nevada, Lieutenant Ruff had had an opportunity to bring his wife and family over to live the idyllic lifestyle of the Hawaiian Islands, but both had decided that in the rising tensions of the day it was a potentially dangerous location to bring a family. They were soon to have their fears confirmed. Just before 0700 the Nevada’s launch pulled alongside the Solace, and Ruff enjoyed coffee and a light breakfast in the officer’s lounge while Father Drinnan conducted the morning’s services.

At 0600 the assistant quartermaster of the watch roused Ensign Joseph K. Taussig Jr., who had the forenoon watch. Taussig, 21, was the son of a rear admiral who had for the last two years publicly warned of the possibility of a Japanese attack in the Pacific, and so was perhaps better informed of the international situation than his fellow sailors of the same age. Taussig, a junior officer assigned to Nevada’s antiaircraft section, was doubtful of any battleship’s ability to defend itself against attack from the air. He felt that though they were highly trained to man the guns, load, and fire “at a rate of speed which people not involved would not believe possible,” the quality of the overall marksmanship was such that “I can testify with vim, vigor and conviction that we couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn except at point-blank range.”

Being officer of the deck, especially on a quiet Sunday spent in port, was usually a boring affair, with little happening to break up the monotony. Taussig spent the first part of his watch trying to think of something to do. It occurred to him that only one boiler had been carrying the burden of powering the ship during the entire four days the Nevada had been in port. He therefore ordered another one lit. This seeming innocent act would have enormous consequences later that morning.

The Nevada’s captain, Francis W. Scanland, and her executive officer had both gone ashore that morning, leaving the ship in the care of its junior-grade officers. Scanland was visiting his wife in nearby Honolulu and had promised to spend the day with her. After all, it was expected to be a leisurely tropical Sunday; some of the crew was organizing a tennis tournament against sailors from some of the nearby battleships, while others were looking forward to a swim at nearby Aiea Beach. The Nevada, the northernmost ship in Battleship Row, was also the oldest in harbor that day but stuck to a very rigid tradition of presenting colors every morning while in port at precisely 0800, to the accompaniment of the “Star Spangled Banner” as performed by the ship’s band.

Ensign Taussig, as officer of the deck, was also in charge of the morning’s proceedings. But this was the first time Taussig had ever stood watch for the morning colors, and he was uncertain as to what size flag to fly. He quietly sent a sailor over to the Arizona at 0750 to find out which size flag they were flying. While everyone waited in the morning sun, some of the bandsmen later recalled spotting specks of aircraft in the sky far to the southwest. Band leader Oden MacMillan later recalled seeing planes diving on the far side of Ford Island and a lot of dirt and sand thrown upward, but thought it was all part of some elaborately staged drill. The sailor soon returned with the welcome news that they had the correct flag after all. The ceremonial group, now assembled at the ship’s fantail in splendid dress whites, was in the process of running the colors up on the flagstaff when the first Japanese planes began diving on Battleship Row.

According to acclaimed author Gordon Prange, the first bomb dropped nearby was actually aimed at the Arizona, not the Nevada. As the first reports of an attack began filtering up the chain of command, Mrs. John Earle, a neighbor of Admiral Husband Kimmel, the naval commander at Pearl Harbor, recalled watching the opening moments of the attack on her front lawn overlooking the harbor along with Admiral Kimmel, who had stepped outside to see for himself. She described him as staring “in utter disbelief and completely stunned.”

“I knew right away that something terrible was going on,” Kimmel later recalled. “This was not a casual raid by just a few stray planes. The sky was full of the enemy.”

“Gazing toward Battleship Row, they saw the Arizona lift out of the water, then sink back down—way down. Neither uttered a word; the scene was beyond speech,” wrote Prange. “The strike that had transfixed both Admiral Kimmel and Mrs. Earle may have come from the torpedo plane which, having dropped its missile aimed at the Arizona, angled upward over the Nevada’s stern at the exact moment the battleship’s 23-man band struck up the national anthem and the Marine color guard began to raise the flag. The Japanese rear gunner loosed a burst of machine-gun fire; by some freak of chance he missed a solid target of some 25 or 30 men, but ripped the flag as it slid along the pole. The bandsmen kept right on playing.” It had never occurred to band leader Oden MacMillan that once he started playing the “Star Spangled Banner” he could possibly stop. Another strafing run kicked up bits of the wooden deck nearby; the entire band paused and then started again in unison as if they had practiced it that way. Not one man broke formation and ran. “Not until they finished the last note did they break for cover and sped to their battle stations.”

Noted historian Walter Lord points out that the Nevada bandsmen calmly put their instruments away before reporting to their battle stations, “except one man who took along his cornet and excitedly threw it into a shell hoist along with some shells for the anti-aircraft guns above.”

Shortly after 0802, the Nevada went to battle stations and swung into action under the command of her senior officer present, Lt. Cmdr. Francis J. Thomas, with Ensign Taussig as acting air defense officer. Taussig pulled the alarm bell for general quarters. As the ship’s bugler began to blow the call, Taussig took the bugle and threw it overboard; instead he shouted over the ship’s public address system, “All hands to general quarters, this is no drill!” In spite of Taussig’s earlier doubts as to the ability of the Nevada’s antiaircraft gunners, the ship’s log states that at this point : “Machine guns opened fire on torpedo planes approaching on port beam. Members of crew state one enemy plane brought down by Nevada machine gun fire at 100 yards on port quarter.” This may well have been the first Japanese plane shot down that day. The Nevada’s gunners had quickly found the range.

Lieutenant Lawrence Ruff, still awaiting Mass aboard the Solace, heard the first bombs begin to explode nearby. He raced to the starboard side of the officer’s lounge and witnessed the Arizona erupting in a huge cloud of smoke and flame. The blast from the Arizona’s magazines blew gunner Carey Garnett and dozens of other men off the Nevada’s decks and into the water. As he watched, horrified, a Japanese plane flashed by, its red meatballs clearly visible on its wings. Ruff then knew exactly what was going on.

Father Drinnan immediately dismissed his flock; he and Ruff caught the launch to return to the Nevada. From their little boat afloat in the middle of the harbor they had an excellent vantage point from which to witness the attack. Ruff saw tracers arcing up toward the Japanese planes from all directions and found himself wondering, “What the hell is keeping those Jap planes up there?” He soon realized that the shells were exploding too far below the planes to do much damage; their fuses had all been set incorrectly in the haste to open fire. Alone and undefended in the middle of the attack, the Nevada’s launch was strafed only once, bracketed in the water by a passing fighter’s machine guns before they reached the relative safety of their ship. Ruff ordered the helmsman to swing the launch under the Nevada’s stern as protection from further Japanese attack. As soon as both men climbed aboard the Nevada, the launch returned to the Arizona to assist in removing the wounded.

Ruff served as Nevada’s communication officer. As soon as he boarded the ship he discovered that most of the Nevada’s senior officers were absent and that those present would have to assume duties for which they had not been trained. Ruff made his way to his station in the Nevada’s conning tower, where he checked on those personnel present and tested the communication circuits. Lt. Cmdr. Thomas was the most senior officer present. However, Thomas was several decks below at his duty station, close to an interior ladder that ran through a tube 80 feet up the height of the ship. As soon as they were able to communicate, they quickly agreed that Thomas should remain in charge of the ship below decks while Ruff took care of topside duties.

Ensign Charles Merdinger was just getting dressed when the first bombs fell. As he pulled on his clothes, he heard someone outside his stateroom yell, “It’s the real thing! It’s the Japs!” In his haste to complete dressing he remembered putting his foot completely through his sock.

A group of planes from the Japanese carrier Soryu soon began a bombing run on Battleship Row, scoring hits on both the Tennessee and West Virginia. A second group of five aircraft followed shortly, dropping five near misses in perfect echelon alongside the Nevada. Japanese strike commander Mitsuo Fuchida still had a group of high-level bombers orbiting in a great circle over Honolulu. He now brought them in, ordering them to make another run over Battleship Row. This time heavy smoke obscured the Nevada, Fuchida’s original target of choice, so the bombers shifted their attention to a ship alongside the inner row of battleships that appeared not to have been hit yet, the Maryland, scoring several hits in the process.

Below decks Warrant Machinist Donald Kirby Ross had just completed shaving when the attack began. It was the day before his 31st birthday. As a youngster he had spent his life moving among numerous foster homes. The Navy had given him a home, and he felt as if he had finally found his place in the world. At the first sounds of battle, Ross reported to his duty station at the forward dynamo room, which contained the controls for the large electrical generators that powered the battleship, fed power to the guns above, and illuminated the darkened passageways below. In an emergency, he reasoned, the Nevada might need power to get underway.

The difficulty in raising steam and getting underway that all capital ships of the day suffered from was also one of the chief causes of their destruction that December 7. It usually took a minimum of two hours to fire the huge boilers that powered a battleship, raise steam, and began turning the large screws that moved the fighting ships through the water. Such large ships then usually required the assistance of anywhere from two to four tugs to maneuver through the confines of a landlocked harbor, and the services of a civilian harbor pilot, an experienced and skilled captain, and a navigator.

Most battleships at port, sitting idle, usually kept no more than one of their four boilers lit, usually to power the generators that provided electricity needed for life aboard ship. Thanks to Ensign Taussig‘s foresight, two of the Nevada’s boilers were now fired up, the second having been online for nearly an hour. Two were normally insufficient to raise enough steam to move a ship out of harm’s way, but on that Sunday morning that was enough to make the difference between life and death. While the nearby Arizona mushroomed in a fireball from a direct hit to her magazines and bombs rained down across Battleship Row, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Edwin Hill led a hastily gathered crew to the wharf where Nevada was tethered. Below, thanks to Donald Ross’s efforts in the forward dynamo room, the Nevada was quickly coming to life.

Japanese Zero fighters swooped down out of the bright morning skies to continually strafe the Nevada’s decks. Oblivious to the danger, Hill managed to reach the pier and cast off the mooring lines. Just as the first attack wave ebbed, the big vessel slowly began to move away from the dock. Hill jumped from the pier and swam to the slowly moving battleship to help direct its escape. Time was quickly running out; an ocean of burning oil from the Arizona was slowly moving toward the Nevada’s bow, threatening to engulf her in flames.

Against all odds, Ruff began moving Nevada out of the harbor aided by excellent cooperation from the two engine rooms below and from helmsman Chief Quartermaster Robert Sedberry at the wheel. From his post high up in Nevada’s conning tower, Ruff selected two landmarks on Ford Island to help him navigate the 30,000-ton ship out into the main channel. He suddenly heard someone demanding to be let in and discovered that Francis Thomas had climbed the 80-foot ladder from below. Ruff and his men removed the floor gratings, opened the hatch, helped Thomas up, and briefed him on what Ruff was trying to do. Thomas quickly agreed with Ruff’s plan of action, and at 0840 the Nevada was officially underway with Thomas at the conn and Ruff acting as navigator in the conning tower.

By this time the starboard antiaircraft conveyor was now out of action, so men began passing ammunition to the battery by hand. As the Nevada crept past the smoldering wreck of the Arizona, intense heat from the fires forced some men to turn their backs and hug shells with their bodies to keep them from exploding. Someone threw a line to three Arizona survivors in the nearby water; they were pulled aboard and helped man one of the Nevada’s guns. Seeing the Arizona totally destroyed came as a “terrible shock” to Ruff, and in spite of the ongoing attack he could not help but speculate about the fate of many of his Naval Academy classmates and friends aboard her. They passed so close to the Arizona, Thomas felt he could have lit a cigarette from the blazing wreck.

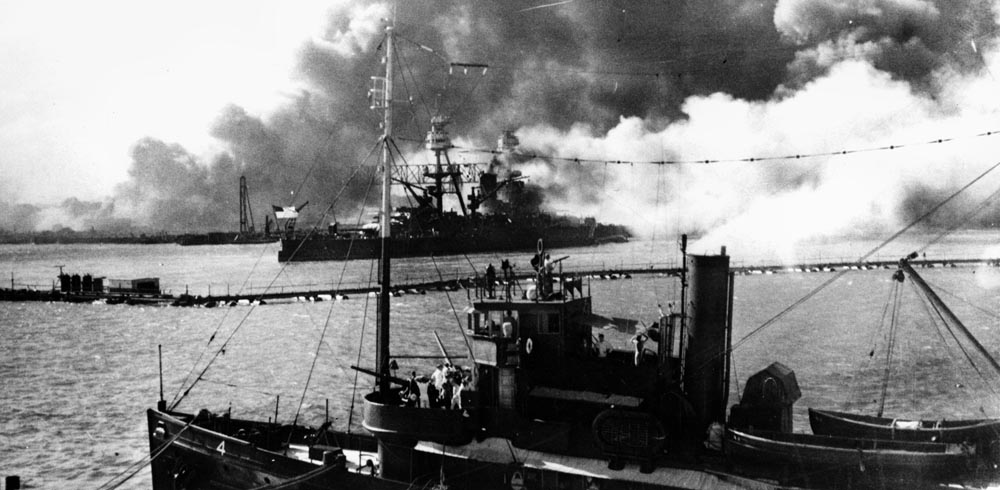

While Fuchida’s second wave began its assault on the helpless ships below, incredibly, under the guidance of junior grade officers and without the assistance from a single harbor tug, the old dreadnought backed out of its berth, away from the blazing hulk of the Arizona, and began steaming away from Ford Island, heading toward the open sea just outside the harbor. The Nevada had taken less than 45 minutes to get underway, a procedure that would normally have taken two full hours. It was a totally unexpected event, and men on all sides began cheering and waving their caps as the Nevada slowly built up speed, knot after agonizing knot, and passed the carnage that was being inflicted on Battleship Row, its battered stars and stripes proudly fluttering from its flagstaff.

A few of the smaller ships, such as tugs and ferries, blew their horns beneath the din of battle to speed the Nevada on its way. Baker First Class Emil Johnson aboard the minesweeper Tern saw Nevada slipping down the main channel and remembered thinking, “Well, there’s one that’s going to get away.” Many Pearl Harbor survivors later recalled the thrilling sight as an event that gave them not only pride but a renewed determination to resist the Japanese with whatever it took.

The Nevada’s effect on those watching could not be underestimated; it was immediate and electric. Photographer J.W. Burton watched from the Ford Island shore, snapping a series of historic photographs. Lt. Cmdr. Henry Wray stood transfixed, watching from 1010 dock. Quartermaster William Miller stood watching awestruck from the deck of the stores issue ship Castor in the Navy’s sub base. To most men she was the finest thing they saw that day. Through the thick, black smoke Seaman Thomas Malmin caught sight of the flag on her fantail and recalled that the “Star Spangled Banner” had been composed under similar conditions.

Ten minutes before getting underway, the Nevada took her first torpedo hit near frame 40. “The plane came in very close, about midway down the channel, dropped its torpedo and turned right,” recalled Ensign John L. Landreth, stationed in the antiaircraft directory. The torpedo jarred loose the director’s synchronizer from the range finder, forcing it to temporarily switch to local manual control. Landreth did not witness the attacker being shot down but understood it had been hit and riddled by one of Nevada’s machine gunners, crashing just astern of the ship. This may have been a Mitsubishi B5N Kate from the Japanese carrier Kaga, the Nevada’s second reported kill of the morning. The pilot struggled to get clear and floated face up past the ship until he was dispatched by a well-aimed shot.

Marine Private Payton McDaniel vividly recalled seeing the torpedo’s silver streak heading toward the port bow, just below the two main turrets. From pictures in magazines of other torpedoed ships he fully expected the Nevada to erupt in flames and break in two. He was more than a little surprised when all he felt was a slight shudder followed by a brief list to port.

Then a bomb dropped from a Japanese Aichi Val dive bomber struck near the starboard antiaircraft director. Joe Taussig was at his station there, standing in the doorway, when it hit. He was thrown against the solid steel deck by the explosion and was amazed to find his left leg tucked under his arm. “That’s a hell of a place for a foot to be,” he thought, then was surprised to hear Bostwain’s Mate Allen Owens, standing next to him, say the exact same thing. Either a bullet fragment or a piece of shrapnel had passed through his thigh and struck the ballistics computer in front of him. Dazed from shock, Taussig felt no pain; despite repeated attempts to remove him to a first aid casualty station, Taussig refused to leave and insisted on continuing his command of the antiaircraft station until the end of the attack.

“Isn’t this a hell of a thing,“ he said to Owens. “The man in charge lying flat on his back while everyone else is doing something.” Taussig survived his wounds, losing his leg in the process, but spent the rest of the war recovering in various hospitals. For him, at least, his contribution to World War II was over.

In the plotting room five decks down, Ensign Medringer felt like this was all part of a drill he had been though many times before. He realized things were different when he learned through the onboard phone circuits that his roommate Joe Taussig had been hit.

Down in the forward dynamo room, Chief Machinist Donald Ross finally was forced to order his men to leave when smoke, 140-degree heat, and escaping steam overwhelmed his position. He continued to perform their duties on his own a short while longer until he became virtually blind and fell unconscious, ensuring that the Nevada had the power necessary to enable her to continue the fight.

Nevada gradually passed West Virginia, which was slowly settling in the mud. Next came Oklahoma, now capsized, trapping scores of men within. Farther away came the flagship California, fully afire and settling on an even keel. Nevada cleared Battleship Row shortly before 0900. The slowly moving battleship now attracted nearly every Japanese bomber over Pearl Harbor; she became too good a target to pass up. Nevada was hit repeatedly and shaken by near misses, opening her forecastle deck, adding more leaks in her hull, and starting numerous gasoline fires forward and around her superstructure.

Just ahead lay a harbor dredge, the Turbine, still attached to the mainland by its pipeline. Easing between 1010 dock and the floating dredge would have been a real challenge on a normal day. Chief Sedberry recalled doing some “real twisting and turning” to maneuver around the dredge and avoid Japanese attacks at the same time. The Navy always forced Captain August Persson of the Turbineto unhook the pipeline every time a battleship entered or left port, claiming there was not enough room to pass. Persson had always claimed they could do it if they wanted. Now he had seen it with his own eyes. Japanese aircraft, currently diving on the drydocked Pennsylvania, now shifted over to the Nevada; if they could sink her in the channel they could bottle up the harbor for months.

Every available Japanese plane now converged on the Nevada. She was soon wreathed in smoke from her own guns, from numerous bomb hits, and from fires that raged out of control on her forward decks. One bomb penetrated and exploded in Nevada ’s stack, sending heat and acrid smoke throughout the ship’s ventilation system. Sometimes she disappeared entirely from view when near misses threw huge columns of water into the air. Ensign Victor Delano, on the West Virginia’s bridge, witnessed a tremendous explosion from somewhere within the ship that threw flames and debris into the air above her masts. The whole ship seemed to rise up and shake violently in the water.

Bosun’s Mate Howard C. French was in Ford Island’s administration building where he had a perfect view of the action. He watched anxiously as “one dive bomber after another peeled off and went after the Nevada. She hesitated and shuddered,” he recalled, “and I thought she was a goner, but she made it down channel.” Admiral Patrick Bellinger happened to be on the telephone to General Frederick Martin when the Nevada drew opposite the administration building. Like French, Bellinger also thought the battleship was “a goner” and broke into the conversation to exclaim, “Just a minute! I think there is going to be a hell of an explosion here!”

Ensign Landreth later estimated that 10 or 15 bombs missed the Nevada before the Japanese found the range. Then several bombs struck the forecastle in quick succession and exploded below decks, one or two near the crew’s galley, starting numerous fires both fore and amidships. “The bombs jolted all Hell out of the ship,” Ruff recalled. “I could see the Japanese bombs—big black things—falling and exploding all around us.” Ruff’s legs were black and blue for days afterward from being knocked about by the explosions.

Shrapnel and bomb fragments decimated those on deck; one gun crew after another was cut down at its post, but still Nevada continued to put up a murderous barrage. The trio of officers in command of the ship— Ruff, Thomas, and Sedberry—were convinced that the Nevada could make it to the open ocean. But a signal from Vice Admiral William S. Pye, the battle force commander, ordered the Nevada not to try for the outer channel, fearing the threat of Japanese submarines lurking beyond.

Thomas and Ruff reluctantly decided to nose Nevada into the mud off Hospital Point to avoid her being sunk in the channel. Nevada was by now a battered ship. Shortly after 0900 the outgoing current caught the Nevada, wrenching control from her navigators and swinging her completely around. Chief Boatswain’s Mate Edwin Hill rushed forward to drop the anchor and keep Nevada from being crushed against the rocks. Three Japanese bombs landed near the bow, and all trace of Hill vanished in the explosion.

Fires raged around the conning tower, threatening to cut the men off from the rest of the ship. Ruff relayed a plan to a sailor on the dangerously exposed fantail that he would wave a hat as a signal for the sailor to drop the stern anchor. Leaving the main channel between buoy No. 24 and floating drydock YFD-2, Ruff ordered the engines backed full, ran to the bridge wing, and gave the signal. With a clatter and a cloud of rust, the stern anchor plunged into the water and took hold on the bottom. It was 0910 hours on December 7, 1941. The Nevada was at rest at Hospital Point on an even keel.

Having accomplished the near impossible, Thomas now turned his attention to damage control. Ruff left the conning tower and made his way aft. There he briefed the skipper, Captain Francis Scanland, when he finally came aboard at 0915. Within five minutes two tugs were moored alongside, and all men who were not manning the guns keeping the Japanese at bay busied themselves fighting the numerous fires raging aboard. Casualties began to be transferred to the hospital ship Nevada or the nearby naval hospital.

The beaching of the Nevada at Hospital Point imposed an additional burden on the already overloaded hospital; a number of Nevada’s men simply dived off her and swam toward the hospital. Between wounds received in combat and the fires spreading throughout the harbor, many of these men could not walk the short distance to the hospital and collapsed; they were among the worst burn cases treated that day.

Ensign Landreth recalled looking around the now beached Nevada. “We couldn’t get communication with the guns, and everything was apparently abandoned on the boat deck. We had great casualties. The signal bridge was ablaze and had gone up the navbridge and came out on top of our own platform. This fire continued for quite some time and practically destroyed most of the structure up there.”

Despite her severe damage, the Nevada crew was never ordered to “Abandon Ship.” Most officers who had missed her sortie were now coming aboard and organizing firefighting parties despite the handicap of having no ready water on the boat deck. Most of the firefighting came from two tugs while the Nevada’s water mains were either spliced or repaired. “We were trying to get all the ammunition out of the ready boxes to keep them from exploding,” Landreth explained. “We got all the ammunition out of the port side, but on the starboard side one ready box did explode.” By this time other officers had come aboard and taken charge of Landreth’s antiaircraft battery.

Captain Scanland sent Ruff to Admiral Kimmel’s headquarters to report on the Nevada’s condition. Kimmel remained calm but was obviously “in a state of shock,” plying Ruff with questions as to when the battleship would be ready for sea again. But information arrived that the Nevada was in a far worse state than originally thought.

At least one torpedo and six bombs had hit Nevada, mostly forward, with additional damage from as many as a dozen near misses. In his report Scanland added, “It is possible as many as ten bomb hits were received, as certain damaged areas were of sufficient size to indicate that they were struck by more than one bomb.” Everything below decks was wrecked and filled with seawater. Engineering was flooded, salting the boilers and steam piping.

And now another problem loomed. With no bow anchors to hold her fast, Nevada might still slide backward and block the South Channel. At 1035, with the damage control situation stabilized, Captain Scanland prepared to move Nevada to a safer location well clear of the shipping lanes. The two tugs pushed her stern sideways until her bow slid free, then escorted her across the main channel to Waipio Point, where she grounded herself, stern first, at 1045. Her journey had finally come to an end. There she remained until she was refloated for repairs more than two months later.

The Nevada’s fires were reported under control by 1530, and 20 minutes later efforts to remove her dead, totaling two officers and 60 men, and more than 109 wounded out of a complement of 1,500 (two more men were to lose their lives during salvage operations) began. Fires broke out again around 1830 and were not finally extinguished until 2300. Meanwhile, Ruff had found shelter for Nevada’s uninjured survivors in a nearby open-air theater.

Thomas remained aboard, overseeing damage control. Captain Scanland’s after-action report highly praised Thomas, a naval reservist, not only for his skillful handling of the ship during the attack but also for his determined repair efforts. A full two days after the attack Thomas was still on duty, on the verge of collapse from almost continuous work with no sleep. In the months following the attack, both Donald Ross and Edwin Hill would receive the Medal of Honor for their actions that day; Hill’s was presented posthumously to his family.

As darkness fell over Pearl Harbor, rumors began to spread of Japanese landings at various points on Oahu. Almost everyone was certain the Japanese would return with the morning’s light. The men on Nevada were told to be doubly alert for any movement among the sugar cane that ran down to the shore near where the ship lay beached. However, no one remembered to tell the trigger-happy sailors that the ship’s own Marine detachment was patrolling the same area. As Private Payton McDaniel moved through the cane, a man aboard ship shouted that he saw movement. A spotlight was switched on, and Payton froze, hoping that it would not find him. Other Marines quickly understood the situation and passed the word not to open fire. But it was a terrifying moment, for McDaniel knew that this was a night when the men were inclined to shoot first and ask questions later.

Ruff admitted, “Actually I was more afraid of our jittery and trigger-happy American gunners that first night than I was of the Japanese during the morning attack.” Unlike most of his shipmates, Ruff did not believe that the Japanese would return. After surveying the scene of destruction around him, he could see no reason why they should come back.

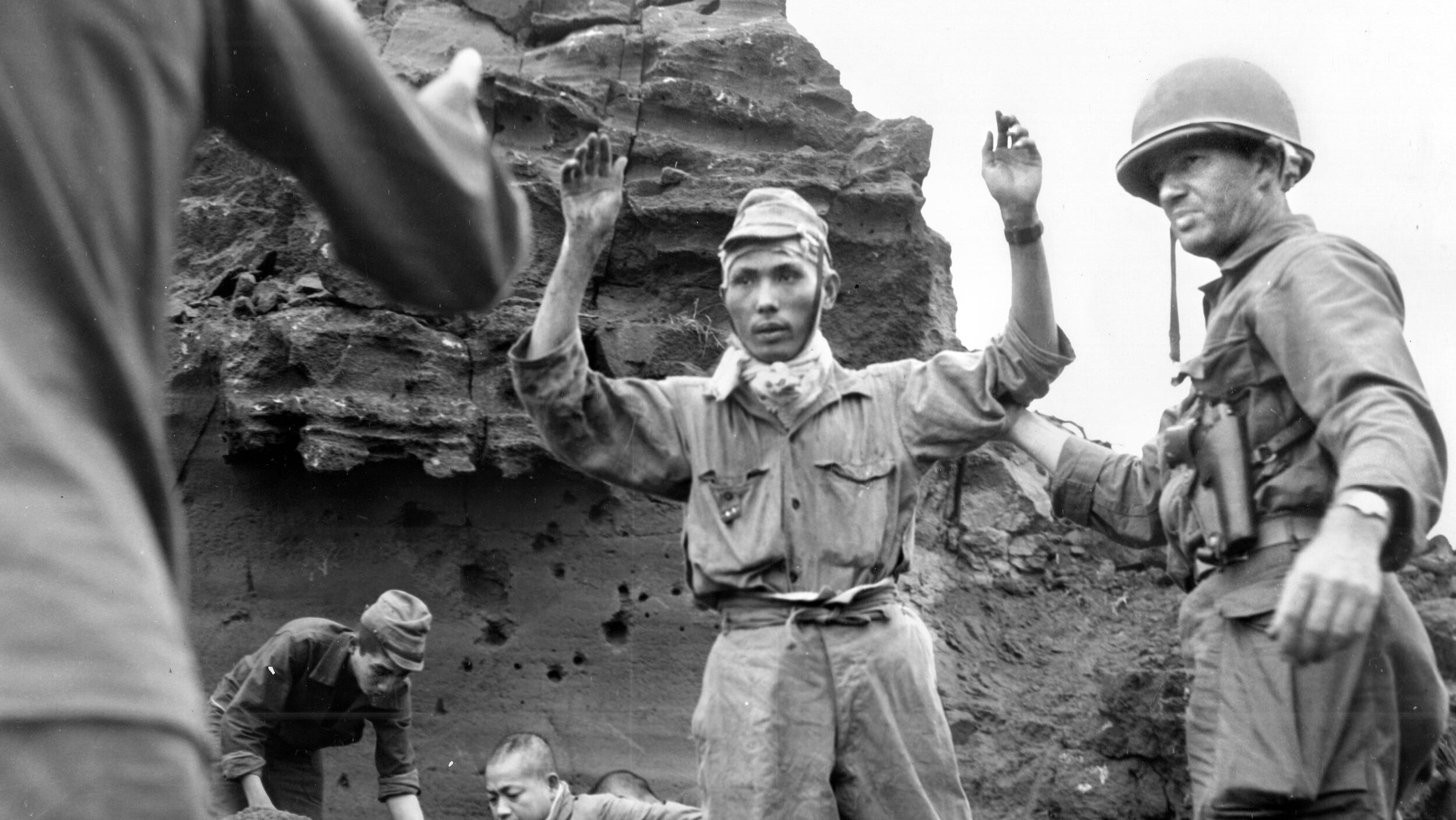

By the day after the Pearl Harbor attack the Nevada had settled to the bottom, still upright and in fairly shallow water, making later salvage and repair efforts that much easier. The Nevada was finally refloated on February 12, 1942, and underwent temporary repairs at Pearl Harbor that allowed her to steam to the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Washington State for major repairs and modernization, which lasted until October 1942. Nevada then sailed for the island of Attu in the Aleutians to provide fire support for the recapture of that island in May 1943. She then steamed for Norfolk for further work, which changed the old battleship’s appearance so that she more closely resembled those of the South Dakota class.

Nevada sailed on several convoy runs in the Atlantic until she headed for England in April 1944 to prepare for the Normandy invasion. June 6, 1944, found her off the beaches of France as flagship for the operation, providing close fire support for the troops struggling to gain a beachhead on the coast of Normandy. Her crew was praised for “incredibly accurate” fire in support of troops ashore, sometimes just 600 yards in front of the advancing Allied forces. She then headed to the Mediterranean to assist in the invasion of southern France from August to September 1944. She sailed to New York to have her gun barrels replaced and next saw action against the Japanese off both Iwo Jima and Okinawa in early 1945. She was hit by a kamikaze off Okinawa, which killed a further 11 men and wounded 49, while also knocking out both guns of her No. 3 turret.

She did a brief stint of occupation duty in Tokyo Bay at the conclusion of the war and then returned again to Pearl Harbor. At over 32 years old she was deemed too old to be kept in the postwar fleet and thus ended her life as a target ship for the first Bikini atomic bomb test of July 1946, in which she was painted an “ugly reddish-orange” to help the bombardier’s aim.

Tough old Nevada, which the Japanese tried so hard to sink, not only survived this nuclear test but a second as well. But by this point she was heavily damaged and found to be extremely radioactive. Nevada was towed back to Pearl Harbor one last time where she was formally decommissioned on August 29, 1946. After being thoroughly examined, her final sortie came on July 31, 1948, when the USS Iowaand two other warships used Nevada as a target for gunnery practice.

Still these three ships failed to send Nevada to the bottom; she was given a coup de grace with an aerial torpedo hit amidships, finally sinking about 65 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor. She proved in the end to be a lady as tough as the men who served aboard her.

Author and researcher Joseph M. Horodyski resides in Brook Park, Ohio.