By William G. Dennis

Even after the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the Japanese were still in a commanding position in the western Pacific. They still had more of every kind of military and naval resource, but the Solomon Island campaign that had begun in January 1942 would change that. By the end of the campaign, the Japanese would lose the initiative in the Pacific and would no longer have the strength to stop Allied advances. Bloody battles lay ahead, but now it was a different war.

There were a number of reasons for the eventual Allied victory. The Japanese made some terrible strategic and tactical mistakes. Overconfidence—“victory disease”—caused many. They were willing to fight in awkward circumstances and at the end of a painfully vulnerable supply line. At the same time, the Allies’ strength was growing as they deployed new units on the ground, at sea, and in the air and introduced new weapons, innovative tactics, and superior aircraft.

Allied losses during the campaign were painful, but Japanese losses were shattering. That was partly because Allied strategic and tactical moves were better thought-out than those of the Japanese. In addition, the Australian coastwatcher organization and the American “Black Cat” PBY Catalina flying boat squadrons made substantial contributions to minimizing Allied losses and ensuring that Japanese losses were ruinously high.

The coastwatchers were initially set up by the Australian government, which needed observers in Australia’s sparsely inhabited Northern Territory. Local volunteers were trained and given a “telaradeo,” which was capable of both voice and Morse code operations.

When the Australians gained control over the Solomons after World War I, they assigned district officers to represent the “Government.” Their administration was benevolent. Intervillage warfare and head hunting were suppressed. A system of medical practitioners was set up that provided the islanders with a modicum of medical support. On the whole, the natives were sincerely appreciative of that support and had a positive attitude toward the Australian administration.

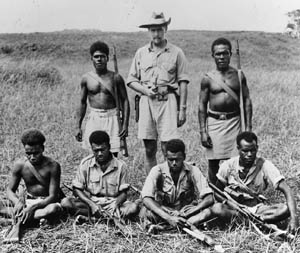

As war loomed, the coastwatcher system was extended into the Australian-controlled islands. District officers and selected planters and miners were enrolled—men who had been in the islands long enough to adapt to the heat and humidity. They were people who, as one historian put it, “knew how to live in the jungle, how to handle the natives, how to fend for themselves.” Events showed it was a sound policy.

It was also important to have old hands for the job because disease can make the islands a miserable place; yaws, dysentery, and blackwater fever are just some of the diseases that afflict people living there. When the Marines left Guadalcanal, 75 percent had malaria. There are also plenty of dangerous pests like the centipede that bit a chief scout on Rendova and left him in agony for two weeks.

At the beginning of the war, the coastwatcher operation was headed by Commander Eric Feldt, who had set up the network that extended throughout the Solomons, New Guinea, and the smaller islands north of it. Feldt codenamed the network “Ferdinand,” after the Walt Disney cartoon bull character that preferred smelling flowers to fighting.

Feldt wanted his people to be covert and not engage the Japanese if at all possible. He wanted information on Japanese movements and, as the air war picked up, weather reports. He felt that the information they could provide was far more important than any pinpricks they might inflict. He was correct; their warnings would have a decisive impact on the campaign.

There were never more than about 15 coastwatchers in the Solomons, plus a few American assistants; several watchers on the northern island of Bougainville were killed. Things could quickly get hairy even in the air. When coastwatcher Dick Horton was sent to reconnoiter the Ontong Java Atoll, north of the Solomons, he flew in a PBY. On the way back, a patrolling B-17 tried to shoot it down. The Japanese had captured a PBY, so Horton’s pilot was supposed to flash a recognition signal to the B-17 when the bomber challenged it. The PBY did not see the challenge, so the bomber opened fire.

The district officers continued to try to help the natives even as their control crumbled during the Japanese advance. When the coconut planters fled, they left hundreds of contract workers stranded, so the district officers made strenuous efforts to get those men back to their home islands.

On Bougainville they were not completely successful, and coastwatchers there purchased tracts of land from the local villages so the stranded men could plant kitchen gardens. In contrast to the Japanese, the watchers were also free with their medical supplies as long as they lasted.

When Japanese pressure forced the watchers still free on Bougainville to withdraw by submarine, the coastwatcher headquarters on Guadalcanal ordered one watcher to leave his native scouts and carriers on the island, as there was not sufficient room for them on the sub. He deliberately failed to rendezvous with the submarine. A second submarine trip had to be scheduled to retrieve him—a sub with room for all his party.

The missionaries in the islands were another group that had earned the natives’ respect because of the medical help they gave and their obvious good intentions, but generally they tried to stay neutral in the conflict. Japanese atrocities and random acts of cruelty directed at missionaries and natives alike made some side with the Allies.

Father Emery de Klerk on the south shore of Guadalcanal began by rescuing a downed American flyer. His resistance to further involvement dissolved when the Japanese wantonly slaughtered some elderly nuns. Before the Japanese evacuated the island, he was commanding his own small war band and wearing the uniform of a second lieutenant of the U.S. Army.

The coastwatchers could not have existed without the support of the natives. About 400 Melanesians served with the coastwatchers, another 680 with the Solomon Islands Protectorate Defense Force, and about 3,200 served as laborers. Most natives subsisted on produce from their communal gardens and the fish and other seafood they gathered.

Generally the people who wrote about the character of the natives were unstinting in their praise. When the Japanese landed on Guadalcanal at Lunga Point to build their airfield, the first detailed information about it came from one of the “police boys” who volunteered to serve in a Japanese kitchen.

Throughout the campaign natives took grave risks to rescue downed flyers and shipwrecked sailors. Then they often spent days of dangerous work getting them to a coastwatcher.

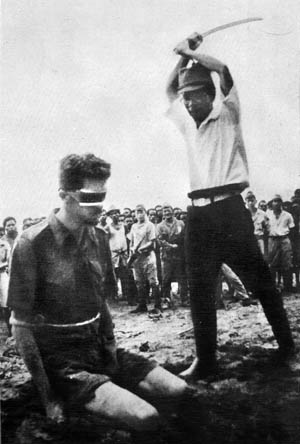

With a few exceptions they were encouraged to stay away from the Japanese, but that did not stop the Japanese from killing or capturing hundreds of natives. It was sometimes hard for the natives to see a reason for restraint when Japanese landing parties looted villages and pillaged gardens as happened one day when the Japanese sent eight men to set up their own coastwatcher station on the south coast of Guadalcanal. The depredations infuriated the local villagers, so they struck back a few nights later. They killed all but one radio operator, who fled into the jungle never to be seen again.

A particularly senseless atrocity prompted watcher Dick Horton to write, “This was not the only case in the Solomons in which the Japanese showed their cruelty and practiced their belief that anyone not a Japanese could be regarded as Kichibu, or beast.” Watchers and scouts were sorely tempted to ambush isolated parties.

Even when cruelty was not involved, there was friction between natives and the Japanese. The occupiers paid little for the supplies they commandeered and for the labor they demanded. Often they lived in such rough and squalid circumstances that the natives had little respect for them.

It was uncertain that the watchers could remain operational after the Japanese occupied the islands, but fallback positions, where provisions and gasoline were stored, were prepared in the jungle. The watchers on Bougainville—Jack Reed in the north and Paul Mason in the south—were able to fall back and keep apprising the Allies of Japanese movements. A few weeks before the Marine landing on Guadalcanal, they were ordered off the air to minimize any chance of their being put out of action before that landing.

The campaign that most clearly demonstrated the coastwatchers’ usefulness began with the battle for Guadalcanal. On August 7, 1942, a force of inadequately trained U.S. Marines landed in what they called Operation Shoestring because they had only a fraction of the supplies and equipment their leaders thought necessary. Their objective was to capture the Japanese airfield and surrounding area, finish building it, and turn it into an Allied air base.

The landing, however, managed to surprise and overwhelm the small Japanese force on the island, enabling the Marines to finish the airfield (Henderson Field) so it could be used by Marine and Army aircraft.

Over the next few months the Japanese made more landings in an effort to build up a force strong enough to expel the Americans. Finally, the Japanese effort collapsed, and the sick and starving remnants of the Japanese forces were withdrawn. Much the same sequence of events occurred on several other islands later in the campaign.

After Henderson Field on Guadalcanal became operational, Japanese naval surface forces avoided the island during the day, but after some sharp and expensive night engagements off the island the Allies ceded night control of those waters to the Japanese. This allowed the Japanese to bring in reinforcements and supplies to their troops via what was dubbed the “Tokyo Express.”

Groups of fast Japanese ships would form near the Shortland Islands and would time their voyages to put them within bomber range of Guadalcanal just before dusk, run in, offload, and try to be back out of range by dawn. Information supplied by the coastwatchers, patrolling aircraft, and signal intelligence made those runs harder and less effective.

There was enormous variation between the experiences of the several watchers. District officer and coastwatcher Martin Clemens hurried back to the islands from leave in Australia when he heard about Pearl Harbor. At his insistence, he was assigned as an assistant to Dick Horton, who was then stationed on Guadalcanal. They moved back into the hills when they got the first report of the Japanese occupying the nearby island of Tulagi

Another stay behind was District Officer Donald Kennedy, who set up shop at Segi Point near the south end of New Georgia Island. He had a talent for dealing with the natives and for keeping the primitive electronics of the day working. By the time the advancing Allies reached him, he had gained a reputation as a formidable warrior.

Kennedy had recruited a “half-caste” native medical practitioner named Geoffrey Kuper, the son of a German planter and his native wife. Initially Kuper worked on getting stranded contract workers back to their home islands. On his own he rescued an aviator from theaircraft carrier USS Enterprise,who was shot down during a strike on Tulagi.

His rescue work was so effective that Kennedy set him up with his own coastwatcher station. He established it on Tataba just in time for the big air battles as the Japanese attempted to knock out Henderson Field; over the next few weeks Kuper and his scouts rescued dozens of downed flyers.

Signal intelligence was of paramount importance in the vast spaces of the Pacific, but the coastwatchers were invaluable in the narrow seas around the Solomons. The Allies actually began to benefit from the coastwatchers before the invasion when Paul Mason reported Japanese ships heading for the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Japanese air attacks against Guadalcanal launched from fields around Rabaul would pass over Bougainville. Once the battle for Guadalcanal began, both Mason and Read began reporting on the Japanese bombers as they headed for that island. The Allied commanders showed that they understood the value of the coastwatchers by briefing their headquarters about planned operations so that the watchers could be placed to best advantage.

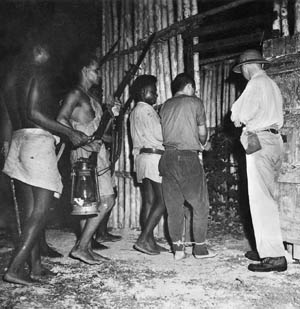

After the Marines landed on Guadalcanal, the coastwatchers at large on the island came into their perimeter and set up a Solomon Islands headquarters. Feldt sent his deputy, Lt. Cmdr. Hugh Mackenzie, to take charge of that headquarters.

But Japanese naval thrusts were getting past Bougainville and New Georgia unobserved, thus showing the need for more watchers, so teams slipped into the jungles of Vella Lavella and Choiseul. Nick Waddell, who had been stationed on Choiseul previously, and Carden Seton, a former planter in the islands, were chosen for that station, while Henry Josselyn and John Keenan established the post on Vella Lavella. There was too much Japanese air activity in the area to fly them, so the teams went in by submarine.

Josselyn and Keenan made it across the coral reef that ringed the island in spite of a leaking rubber raft and not being able to find a gap in the reef. Without making any contact with the natives, they made their way to the deserted Mundi Mundi plantation house and set up shop in a camouflaged lean-to on a nearby hill, only to have their teleradeo break down almost immediately. Fortunately, friendly natives happened by so they were able to arrange for relays of canoes to take Josselyn 150 miles to Kennedy’s post.

After requesting parts for the machine only to have them destroyed when dropped from an airplane, Kennedy gave Josselyn his own radio. He was sure he would be able to fix one he had pulled from a crashed Japanese plane. Eventually the natives returned Joselyn to Mundi Mundi, where the station became operational.

Waddell and Seaton had an exciting time getting to their station on Choiseul. As the submarine was moving into position to launch their rubber rafts, word came that the Tokyo Express, a fresh Japanes destroyer convoy, was running and the submarine was to take station to intercept the enemy. The submarine found the convoy, launched a torpedo attack, and was depth charged in return.

Eventually the submarine returned to the section of the coast where the men were to land. They fought their way across the fringing reef and onto shore, barely getting their supplies and the rafts under cover before daylight. The station was soon operational.

When the Japanese established a seaplane base on Santa Isabel Island, Guy Cooper and a team of native scouts were deployed to keep an eye on it. Scouts offered the Japanese at the base fish and other food and soon had the run of the whole facility. A second post was also established and manned on that island by J.A. Corrigan.

All of these posts were operational by March 1943, which put Japanese ship and air movements through the islands under almost constant surveillance. This allowed the Allies to mount attacks that seriously interfered with Japanese attempts to build up bases in the islands. When Japanese aircraft flew south from Rabaul, watchers on Bougainville could give Guadalcanal and ships in nearby waters about two hours’ warning of an impending raid.

Fortunately, even without coastwatcher warnings the time of day when Japanese aerial attacks on Guadalcanal could be expected was quite predictable. The range to their targets was such that there was no fuel or time to do anything but fly the most direct route. In order to return to base before dark, the raid had to reach Guadalcanal about noon.

These distances were a long way for a damaged aircraft to fly, and a great many Japanese aircraft went down somewhere along the “Slot,”—the strait between New Georgia and Santa Isabel. If the aircrew made it safely to the surface, there was a good chance they would end up in the hands of the natives. The lucky ones were turned over to a watcher and sent back to Guadalcanal, where they were a useful source of information.

To give them more flexibility in timing their raids and to give their flyers a better chance of making it back, the Japanese began building airfields in the northern Solomons. They expanded the one the Australians had begun on Buna and began building another one near Mason’s station on Matabita Hill. This forced him farther back from the coast, which interfered with some of his observations. It was also the beginning of serious Japanese efforts to capture him and Reed.

This was one of the few times the Japanese made determined efforts to eliminate coastwatchers; apparently they finally grasped the damage that Reed and Mason were doing. It was easy to see the relationship between coded messages from the interior of Bougainville soon after Japanese air raids passed overhead and the flights being intercepted as they neared Guadalcanal.

Reed’s and Mason’s positions were also more tenuous than those of most watchers. There were thousands of Japanese on Bougainville, and as the campaign progressed their bases were multiplying. This made Japanese claims plausible that the day of the white man in the islands was over and most of the villages were under Japanese guns.

Whatever motivated them, a number of villagers began cooperating with the Japanese, providing them with porters for their patrols and, more importantly, information on the watchers’ locations. Reed and Mason retaliated by calling for air attacks on the collaborators’ villages.

A watcher on Guadalcanal named McKenzie reinforced Reed with several more watchers, replacing the Australian commandos that had been in the bush since the beginning of the campaign. Reed used the new arrivals to reestablish his network, but by then the growing strength of the Japanese and the disaffection of the natives made it impossible to continue.

One by one the new posts were overrun and forced off the air. Several watchers and scouts were killed in the attacks and a number captured. Some were executed on the spot and others taken prisoner to be executed later.

The decision was made to evacuate the remaining watchers and scouts. They were no longer producing useful information, and other posts were now in position to substitute for them.

Injured flyers and the remaining missionaries and Chinese merchants were also evacuated by submarine. The decision was a sound one, although there were more casualties on the way to the coast.

Another station was set up when the Japanese began building another airfield at Vita on the south coast of Kolombangara. The American attack on the big base at Munda was in the offing, and there was considerable barge traffic through that area as the Japanese moved to reinforce it.

The men sent to run the station were not the old island hands Feldt liked to recruit. One of them, Arthur Evens, had been a purser on an inter-island steamer but had little experience on shore. The man sent to work with Evens, Frank Nash, seemed an even odder choice. An American Army Air Corps corporal, he had grown up on a ranch in eastern Colorado and had been so eager to get overseas that he was ready to volunteer for the infantry. Instead, he was assigned to a signals construction company that was sent to Guadalcanal to set up communications for Henderson Field. When the company was being withdrawn, he volunteered to stay and work for the coastwatchers.

The two men actually worked well together. They had their most memorable moment when they woke to find four Japanese destroyers offshore that had run into a newly laid American minefield. One had sunk, two were damaged, and the fourth was picking up survivors. Evens and Nash called in aircraft that sank the two damaged ships and shot up the fourth. They also had the distinction of being the watchers who made contact with John F. Kennedy and the crew of PT-109in August 1943.)

About the only criticism of their work was that the few natives in the area could not spare much food and the two were not up to foraging in the jungle; they subsisted mostly on Spam and C-rations.

In the early days of primitive radar, the difference between the available American and Japanese fighters made the coastwatchers’ warnings crucial to holding Guadalcanal. Japan’s dominant fighter in the campaign was the Mitsubishi Zero. It was a fast, agile aircraft that could climb quickly. To achieve this, it was built with a light airframe and was not constructed with armor or self-sealing gas tanks. Like most Japanese aircraft, the Zero was somewhat fragile and vulnerable to gunfire. The fragility of Japanese aircraft actually became a bigger problem as the war went on and metal shortages worsened.

America opted for sturdy airplanes that could take great punishment, equipping them with self-sealing gas tanks and some armor. Most of them were armed with multiple Browning .50-caliber machine guns, which outranged anything on Japanese airplanes.

In a typical engagement, the watchers on Bougainville would sight formations of bombers coming in from the fields around Rabaul, joined by fighters from the field on Buna. When the Japanese formations reached the vicinity of Guadalcanal, the Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters would dive out of the sun and rake the bombers. If a Zero got on a single Wildcat’s tail, the Wildcat’s pilot could go into a fast dive; if a Zero attempted to dive as fast as a Wildcat, its wings might tear off.

American aircraft regularly savaged Japanese raids. Typically the kill ratio in such an engagement was “wildly disproportionate” in favor of the Allies. Later in the Solomons campaign, the Wildcat was superseded by more modern aircraft like the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the Vought F4U Corsair that could outperform the Zero in every way but in making tight turns.

Few sources agree on how many Japanese aircraft were brought down during the first series of raids on August 6 and 7, 1942. Eric Feldt puts the casualties for the first unescorted raid at 23 of the 24 Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers making the attack. Reed and Mason, who had reported the oncoming raid as it passed over Bougainville, listened in on the chatter during the fight that took place just north of Guadalcanal. At one point about eight Japanese aircraft were simultaneously falling out of the sky. Hearing that the results were so dramatically in the Allies’ favor must have made Reed and Mason feel the risks they were taking were justified.

Whatever the actual losses, they were unsustainable, and after a few days the attacks ceased while the Japanese brought in additional aircraft from the Carolines. The Japanese would periodically renew the raids as they made another attempt to reconquer the island; the heavy losses would continue.

The coastwatchers assisted the Allies in a variety of other ways besides air raid warnings. They kept tabs on Japanese supply and reinforcement movements throughout the islands. During the first half of 1943, the campaign became a war of attrition for the Japanese as they suffered severe losses because of the intelligence coastwatchers supplied. Once the Allies began moving north, the coastwatchers moved in close to targeted bases to provide detailed information and even acted as guides for Allied troops.

Assistance with search and rescue of flyers and mariners was important at all stages of the campaign. Clemens on Guadalcanal began rescuing flyers before U.S. forces landed there. The most spectacular example was the rescue of 165 crewmen of the light cruiser USS Helena, whom the watchers hid until the Navy could rescue them.

There was one major exception to Ferdinand’s policy of avoiding contact with the Japanese: Donald Kennedy at Segi Point, who became very active in rescuing flyers. His station became the collecting point for downed flyers in much of the central Solomons. His central location also made him extremely effective in providing information on Japanese movements.

His base was no hut hidden in the jungle but rather a full camp, with mess hall, arsenal, and even a prisoner of war compound. His post could be in the open because it was hard to approach. It was backed by swamps, and naval charts warned mariners of unmapped reefs and shallows.

The Japanese decided to send small patrols to find Kennedy’s compound, but Kennedy knew that if the patrols did not return the secret of his location would be safe. Accordingly, he established a “forbidden zone” around his post and adopted a policy of ambushing the Japanese and killing or capturing all that came within it.

When a scout reported two Japanese supply barges tied up five miles away, Kennedy gathered a force of 23 men, including a downed flyer awaiting rescue, and attacked. All of the enemy crews were killed, weapons and supplies were taken, and the barges sunk in deep water. Presumably the Japanese never learned what happened to them.

Another mysterious disappearance took place when old and nearly blind Chief Ngatu learned of a Japanese post on an island 30 miles from Kennedy’s camp. With the Aussies’ permission, Ngato and six of his men slipped into the Japanese camp and slipped out with their rifles. The next morning Ngatu’s men used them to take the Japanese prisoner.

Action of this sort boosted Kennedy’s standing with the natives; Ferdinand might be a bit of an abstraction to them, but a good fight was always fun. The chief of the Mindi-Mindi Islands enlisted as a scout and was given a rifle. He ambushed enough Japanese and collected enough rifles to put 32 armed men at Kennedy’s service.

In this way Kennedy built up a force armed mostly with captured Japanese weapons and even more when PBYs came in to pick up Allied personnel; captured Japanese were flown out with rescued flyers. The combination of anger at the Japanese and Kennedy’s example encouraged natives to ambush any small enemy parties that came within reach.

The Japanese continued to push their net of bases farther south. But Kennedy did not move his base even when the Japanese set up an emergency airstrip and base a few miles away at Viru; he continued to ambush their patrols.

Another Japanese air base was established at Munda on the other end of New Georgia from Seti Point and had extremely tight operational security. It was hidden in a coconut plantation where Japanese engineers had wired the tops of coconut palms together and cut off the trunks where the runway was to be, thus suspending the tops in the air and preventing aerial reconnaissance from observing the activities beneath.

Initially, native scouts simply could not get close enough to find out what the Japanese were up to; it took weeks to finally penetrate the base. But their reports were not corroborated until the engineers got careless about replacing the coconut tree tops as they dried out, and sharp-eyed photo interpreters on Guadalcanal spotted the ruse.

Once it was clear that a major Japanese base was being built there, Dick Horton was sent to keep watch on it. From a spot on neighboring Rendova Island, he was able to provide detailed information about activities on the base. Eventually a Marine reconnaissance team slipped into his station. Their observations and the information supplied by the coastwatcher/scout team helped the Marines to plan a landing on beaches close to the base.

Kennedy’s problems with the base at Viru continued to increase. After several patrols and scouting vessels failed to return from trying to penetrate Kennedy’s forbidden zone, the Japanese prepared to send a whole battalion. Kennedy was forced to seek help, but by then he had been instrumental in saving so many flyers that he probably could have asked for anything he wanted.

Almost as soon as Kennedy asked for help, fast attack transports were loading Marine Raiders and an airfield engineering advance party. The move fit well with Allied strategy. Given the aggressive but disjointed Japanese response to the landing on Guadalcanal, it seemed a good plan to land on New Georgia, get an airfield up and running, and let the Japanese waste their strength trying to drive the Allies off. An airfield at Kennedy’s base at Segi Point and an attack on their base at Viru, seemed to be good ways to provoke them.

Construction crews and equipment were soon on the way; within 10 days of the arrival of the main body of engineering troops, aircraft were landing on the field.

The Marines’ attack on the Viru base met a spirited defense, but once it was captured the Allies used its field to pound the larger base at Munda until they were ready to assault it. As on Guadalcanal, once Munda was captured the Allies let the Japanese wear themselves out trying to drive the Allies off. They maintained enough of an offensive posture to keep the Japanese off balance while they strangled their supply lines. Eventually the Japanese tired of the pounding and abandoned the island.

The lumbering PBY flying boats built by Consolidated looked ungainly, so they quickly earned the nickname “Dumbo,” after the popular Walt Disney cartoon character—the elephant with huge ears that could fly. But this Dumbo—a very effective scout, rescue plane, and ship killer—was a workhorse.

The PBY Catalina squadrons based on and around Guadalcanal became an Allied resource that complemented the coastwatchers’ efforts. The PBY had two engines mounted on a wing above the fuselage. It cruised at a stately 90 knots while carrying a fair load of bombs or torpedoes and could do so for about 24 hours at a stretch.

Its crews had complete confidence in it, although its defensive armament was not heavy enough to make the Zeros keep their distance; a Zero could fly rings around a PBY. If caught by one, the best hope for a PBY was to dive for the water’s surface, turning repeatedly. A Zero diving on a PBY had great difficulty staying on target and stood a good chance of flying into the sea.

When they were first deployed to the Solomons, the PBYs were assigned a variety of duties such as spotting enemy artillery positions when Allied ships shelled Japanese bases. As Allied strength grew, the American squadrons concentrated on bombing and search and rescue operations. Australian squadrons handled a variety of duties and provided coastwatcher support.

As commerce raiders, the PBYs could be deployed well north of Guadalcanal—at least on moonlit nights. A veteran of the Catalinas told the author that if he had known they were going 600 miles behind Japanese lines he would not have gone! The same time and distance constraints that meant that Japanese raids on Guadalcanal arrived around noon meant that Japanese convoys that wanted to be in one of their protected anchorages by dawn would be passing through narrow straits at predictable times.

When signal intelligence or coastwatcher reports heralded the approach of a convoy to a PBY, the “Cat” would loiter above the narrow strait and try to spot the convoy.

Japanese sailors knew they were in for it when they heard a PBY’s engine noises and then those noises suddenly cut off. It had throttled back to glide down into a low-elevation release of a bomb or torpedo just before it passed over a ship. The crew of at least one plane scrounged up something to use for nonreflective coating to minimize the effectiveness of Japanese searchlights and make such an attack slightly less hazardous. The Navy was impressed, and shortly after the landings on Guadalcanal a more effective version of the PBY with a nonreflective paint job began appearing, making it perhaps the first “stealth” plane.

More importantly, the PBY came with radar good enough to spot ships and barges on dark nights. Dubbed the “Black Cats,” the radar-equipped PBYs made the aircraft an effective ship killer; one squadron destroyed 157,000 tons of Japanese shipping. The countermeasures the Japanese attempted—night fighter cover for convoys and patrol boats stationed to intercept Cats flying into a Japanese-controlled harbor—made it clear that they hurt the Japanese.

The Allies’ ability to predict the locations of Japanese conveys improved once Henry Josslyn and John Keenan slipped onto Vella Lavella and Nick Waddell and Carden Seton took up a post on Choiseul. Between the Black Cats, PT boats, and occasional forays by bigger ships, running the Tokyo Express became an expensive proposition. On average, Japanese destroyers assigned to the Solomons lasted about two months before they were sunk.

One Japanese countermeasure was to start moving much of their maritime traffic in barges and other small vessels. If they stayed close to land, they were hard to pick out on radar, and they were so small it was hard to put a bomb close enough to do damage.

The PBYs’ answer to the barges was a locally produced mount that added four Browning .50s to the two machine guns already in the nose. Barges were an ideal target for the quad .50s. Black Cats sank dozens of enemy barges. One Cat sank 25 in a single mission.

The Black Cats squadrons rotated between night bombing and other duties. Dumbo flights picking up downed Allied flyers were welcome, if nerve-wracking, missions. If a formation raided a Japanese target and a plane went down, there was usually another plane on the same raid that knew about it and could call for a PBY to pick up any crew that got out.

In other cases, damaged planes tried to limp back to base alone and went down without search and rescue having a clear idea where they were. But friendly natives, coastwatchers, and Black Cats kept these sorts of losses down. A Black Cat veteran proudly told the author that his squadron alone picked up 258 downed flyers.

When a crippled B-17 went down near Bagga Island, most of the crew got ashore, and the natives were there in minutes. A couple of hours later, coastwatcher Jack Keenan arrived with K rations and first aid supplies. As soon as it got dark, the crew was taken to Vella Lavella, where the chief of the village of Paramata had arranged for a hot meal and beds. The next day a PBY picked the men up there and took them to Guadalcanal.

When the coastwatchers got word to headquarters on Guadalcanal that they had people to be picked up, a PBY escorted by fighters would usually be there within a day or two. The wounded got even faster service, and an especially crucial squadron commander was back at Henderson Field the same day he was shot down.

On one occasion the survivors of a sunken destroyer were spotted by a Dumbo. It located another vessel close by and gave it directions to the site. Within an hour the men were picked up.

In a similar situation later in the war, a pilot assumed that there would be heavy losses by the time a surface vessel arrived, so the Dumbo landed and picked 114 shipwrecked sailors out of the water; the overloaded airplane sat there until a destroyer relieved it of its passengers.

On still another occasion, the call for help came in the aftermath of a raid on Kavieng Harbor on New Ireland. Before the mission was over, the PBY landed four times in the harbor, under Japanese shellfire, and on three of those occasions had to stop its engines to get the survivors into the aircraft. All told, 15 flyers were rescued.

Between the coastwatchers and the Dumbos, an airman who made it safely to the surface stood virtually a 100 percent chance of making it back to Allied lines. This had a tremendous impact on morale and helped make the wastage of trained, experienced people far smaller for the Allies than for the Japanese.

By mid-November 1942, the South Pacific was getting major air and sea reinforcements, and by that point in the campaign the coastwatchers were operating at maximum efficiency. They were keeping headquarters well informed and quickly picking up downed flyers and shipwrecked mariners. The Black Cats had shown that they could handle maritime targets from the smallest barge to the biggest capital ships. The Cactus Air Force, as the squadrons based on Guadalcanal were known, had grown to 200 airplanes, half of them fighters.

As the battle for Guadalcanal progressed, the relative strength of the adversaries shifted sharply in favor of the Allies. A look at the Japanese attempts to retake the island illustrates this point; the reinforcements usually took heavy casualties during their trips down the Slot.

After the battalion the Japanese sent on their first attempt to recapture Guadalcanal was destroyed, a regiment was committed. Later a brigade was sent. Finally a whole division, the 38th, was committed. The last attempt was made with the reinforced Hiroshima Division.

The Japanese force assembled off the south end of Bougainville. There were 61 ships there, including six cruisers, 33 destroyers, 17 transports, one large cargo liner, and many smaller vessels; another force of two battleships and escorts was also involved.

Signal intelligence warned of their coming, and the watchers on Bougainville spotted them on November 10, 1943. The coastwatchers and the Black Cats kept tabs on this force as it advanced down the Slot. There was a running fight all the way to the shore of Guadalcanal. Henderson Field was in the fight all day with planes shuttling from the field to the convoy and back again.

Both sides lost naval vessels. The U.S. Navy lost more vessels, but the Japanese lost more tonnage, including two irreplaceable battleships. The Japanese also lost 11 of their transports, and much of the Hiroshima Division drowned. Japanese destroyers picked up about 5,000 shocked, demoralized men without most of their uniforms and none of their weapons and equipment. Three of the transports were beached, and another, already on fire, attempted to beach. All the ships were taken under fire by Marine artillery and essentially destroyed.

This was really the end of Japanese hopes to hold Guadalcanal. A few weeks later, the evacuation began. For the rest of the campaign, the Allies would be moving north through the island chain.

The coastwatchers and the Black Cats, working in concert, played an important part in keeping Allied casualties disproportionately low. Both groups provided vital intelligence. Both inflicted significant casualties, the Cats directly and the coastwatchers by calling in aircraft. And, finally, both were directly involved in search and rescue.

Granted, Black Cats and coastwatchers were not the only reason Japanese losses were so hugely disproportionate to those of the Allies. Signal intelligence complemented the coastwatchers’ input, and cultural factors made the Japanese more willing to take losses; against Westerners, their infantry tactics were insanely aggressive.

The Allied leaders also consistently made good use of the mobility their naval and air strength gave them. The strategy of bypassing Japanese bases and giving the Japanese the choice of expensive evacuations or having their forces wither on the vine was used repeatedly.

Also, Japanese action on Guadalcanal seemed to suggest that if the Allies could build a perimeter on a major island the Japanese could be expected to take heavy casualties trying to break through it and drive them off. An effective Allied response involved limited attacks and choking off the enemy’s supplies. Eventually the Japanese would give up and withdraw. That strategy was used on Vella Lavella, New Georgia, and Bougainville. The Japanese never developed an effective counter to it.

Instead, Japanese leaders regularly put their troops in positions where they were nearly impossible to supply. As Emperor Hirohito put it, “I am tired of hearing that the troops fought heroically and then starved to death.”

Operation Shoestring gives lie to the myth that the Allies simply used their industrial power to bludgeon their way across the Pacific. But the main significance of the Solomon Islands campaign is the aforementioned change in the relative power of the Allies and their Japanese adversaries during that campaign.

Perhaps that change was least obvious on the ground. The Imperial Japanese Army began the war in the Pacific with around 50 battle-ready divisions. The Solomons campaign and the simultaneous fighting in the islands to the west whittled that down considerably. By late 1943, the building of a chain of air bases around Rabaul was complete; the Allies isolated it and took the troops there off the board, obviating the need for a bloody invasion.

Two Japanese divisions, two separate brigades, a tank regiment, a huge force of artillery, and a large number of service troops totaling about 100,000 men were trapped there and spent the rest of the war trying to grow enough vegetables to survive.

In and on the water the change in relative strength was more pronounced. Japan could not begin to replace the major fleet units it lost. Destroyers took less time to build than capital ships, and up to this point in the war 40 new Japanese destroyers joined its fleet—the same number they lost by the end of the campaign.

America lost the same number of destroyers but commissioned 200 new ones during that period. Moreover, using submarines and bombers to run supplies to Guadalcanal and destroyers to get critical parts and personnel to Rabaul removed them from the Japanese order of battle just as if they had been destroyed.

American ships were becoming more numerous and, more importantly, more capable. Take one narrow facet of naval power: the ability to locate one’s enemy at night and engage it effectively. Japan’s training program for night lookouts was unequaled and its equipment was first rate.

In a night fight between surface ships, the Japanese could open fire first and fire more accurately than comparable U.S. units. They could usually hit more effectively because the Long Lance torpedo was more accurate and longer ranged that the American equivalent. The Long Lance remained a formidable weapon, better than even improved versions of American torpedoes.

Radar reversed the balance in night combat. American ships could usually see farther than the Japanese, and the fall of their shells was controlled by the increasingly available SG radar. As Captain Hanima of the destroyer Amagiriput it, “U.S. forces were using radar and we were powerless to prevent them from approaching … guns blazing.”

With the deployment of radar-equipped aircraft, Americans could now see even farther at night, and aircraft could alert American vessels to the location of Japanese ships well over the horizon. The improvement was so pronounced that had it happened earlier the pattern of daytime American control of waters around Guadalcanal and Japanese control at night might not have developed.

The change was most pronounced in the air. The Japanese air arm was strained even before the beginning of the Solomons campaign. At Midway the Japanese had lost four aircraft carriers. The incursion into the Indian Ocean and attacks on British installations on Ceylon cost Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s air groups more pilots. The Battle of the Coral Sea had cost the Japanese an aircraft carrier, including pilots and the nonflying members of the air groups, and rendered still another carrier combat ineffective since it, too, had lost most of its pilots.

Whatever the total losses in Japanese bombers were in those first raids on Guadalcanal, it is clear that the rate of loss was unsustainable. After two days of raids there was a pause in the air activity while additional aircraft were flown in. On several occasions the air groups were temporarily stripped from the Combined Fleet, Japan’s main striking force. It, too, was gravely weakened. This was especially serious since training a pilot to be carrier qualified was so difficult. The last time the Japanese deployed carrier planes to Rabaul, they sent 173 aircraft of which only 53 returned.

By one account the Japanese lost 1,467 fighters and 1,199 torpedo and dive bombers during the campaign. Most of the aircrews were lost, too. It is fair to say Japan squandered its air assets by making so many long-range raids into the teeth of an effective American air defense.

As Japanese air power shriveled, American air power became increasingly dominant. At the beginning of the campaign, aircraft were sinking about one tenth of the Japanese supplies shipped; by the end, it was up to 25 percent. During October 1943 alone, Allied aircraft carried out about 5,600 sorties.

The Japanese policy of keeping an airman in combat until he was killed hurt their air arm gravely. American fighter pilots were in combat for a limited period of time. In the Army Air Forces, it was a certain number of missions. Navy squadrons were regularly broken up, and the surviving flyers were usually posted back stateside. There they were used to impart their experience to fledgling pilots. Not so the Japanese. The splendidly chosen and trained airmen were replaced by less qualified pilots.

As a result, when American forces assaulted the Caroline Islands a few months after the Solomons campaign, the combined Japanese fleet could not sortie. The same thing happened when MacArthur’s forces breached the Bismarck barrier farther west.

A few months later came the next attack in the Central Pacific and the Battle of the Philippine Sea. By this time American flyers who had been flying for two years before being assigned to a carrier air group were facing Japanese flyers whose training had been for three to six months and were stale from more months sitting idly in harbor.

The Americans were flying a new generation of aircraft with substantially better performance than the F4F, while Japanese industry had been unable to produce significant numbers of their planned followup to the Zero. The Americans calledthe Battle of the Philippine Sea the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.

From the beginning of the conflict, Japan’s only hope of winning in the Pacific was to make the cost in Allied lives so high that the Allies would accept a negotiated peace. Dumbos and coastwatchers were among the factors that helped keep the Allies’ human cost relatively low. Poor choices on where to fight and hyper-agressive infantry tactics resulted in high Japanese casualties. Clear strategic thinking by the Allies combined with innovative weapons and tactics also contributed to Japans horrendous casualties.

Japan’s ill-advised decision to fight in such unfavorable circumstances in the Solomons broke the back of its air power and seriously weakened its army and navy, thus paving the way for Allied victory in the battles to come,

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments