By Susan Zimmerman

With war comes untold stories of unbroken spirits. These are universal stories without bounds and sides, some of which remain buried deep in psyches. Then there are those that must be written in order for the survivor to move on. In purging the horrors of war from the mind with words comes an inalienable freedom.

Peter Aage Jorgensen chose the latter some 70 years ago when the young Danish underground member wrote his liberating journal telling the story of his capture, torture, and survival in concentration camps at the hands of the Nazi Gestapo during World War II. The following entries were excerpted from his 32,000-word journal.

JORGENSEN’S JOURNAL

The account of my arrest and subsequent interrogation by Gestapo and imprisonment in concentration camps I wrote as a 19-year-old in 1945, not for the purpose of publishing; the sole reason for writing it all down was to get all the traumatic happenings which could threaten one’s sanity out of one’s system. I was convinced that by forcing oneself to look forward and not dwell on all the horrible, terrible things one had witnessed, and by writing them down, I boxed them in, an end of that.

The writing served its purpose; today I can think about and talk about the happenings without problems. Today I even view myself as having had the privilege to witness Nazi Germany’s collapse from the inside, also to have been imprisoned in concentration camps at a time when the German commander in Denmark, Dr. Werner Best, increased the number of executions dramatically, may have been lucky.

In 1944, the Germans executed, all in all, 42 Danish freedom fighters. In 1945, when they knew they had lost the war, the Germans executed 36 in the month of March alone and 26 in April. The 25th of April they executed nine, just 10 days before they capitulated. They were not executions, they were murders.

Dr. Best was condemned to death, and so was Børge Bendahl, the man who beat and tortured many, including me, but Denmark abandoned capital punishment before these death sentences were carried out and, after a number of years behind bars, they were both let out as free men (in August 2001).

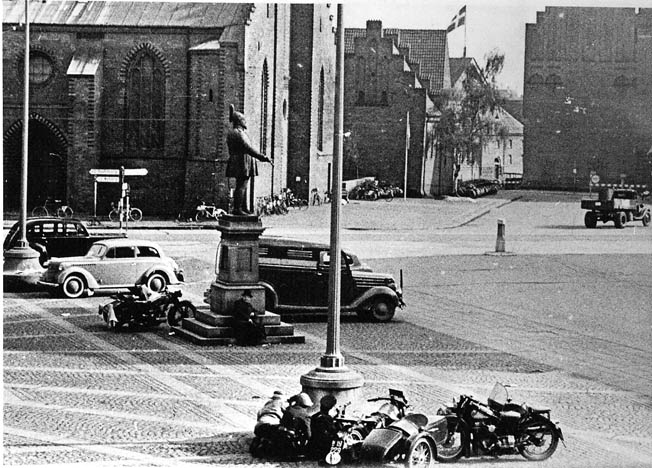

In 1939, just after the outbreak of World War II, my family moved from Sakskøbing to Nykøbing Falster and the first few years we lived in a rented house in Frisegade 19. The house was owned by two sisters of the famous explorer Peter Freuchen, whom I often saw––and looked up to! There I was awakened on the morning of April 9, 1940, together with the rest of the family, to look out on the street where the German soldiers were marching by, after having landed in Gedser. That day I will never forget.

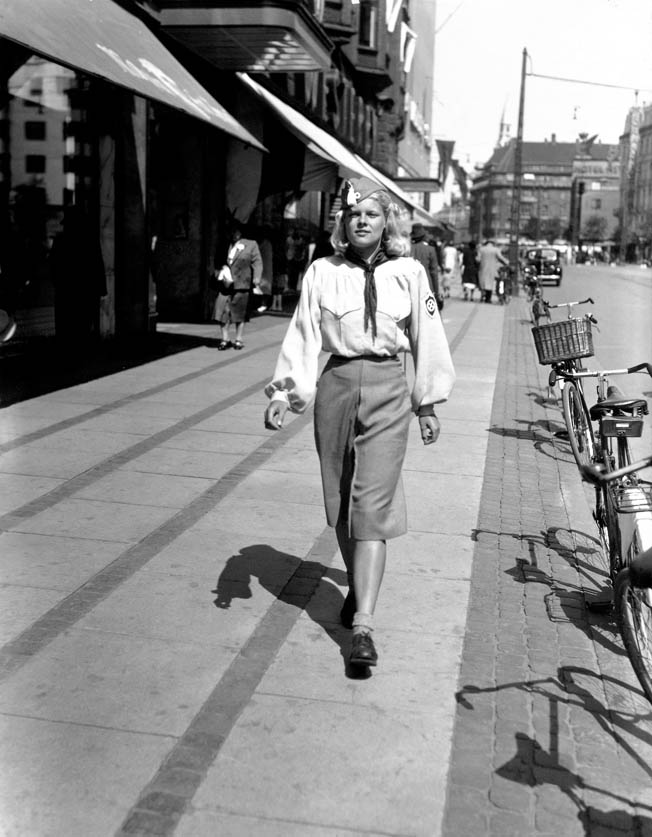

I was an enthusiastic Boy Scout and, through scouting, I gained lifelong friends. When our resistence group was formed, I was 17 years old, and I was accepted only because the group consisted solely of scouts who had grown up together.

After finishing high school (Præliminæreksamen) from Nykøbing Byskole, I became a trade and commerce apprentice at Dahl Bros. Dahl Bros. was located right across from Frisegade 19, where we lived. When two members from our group were arrested by the Gestapo, the remaining group members had to go “underground” in order to hide from the Gestapo. Hiding was easiest in Copenhagen, and that is where we were when the Gestapo caught the rest of us, two by two.

After the arrest and interrogation at Politigaarden (police headquarters) in Copenhagen and the following stays at Vestre Fængsel, Dachau concentration camp, Neuengamme concentration camp, Frøslev Camp, and finally Løderup in Sweden, I returned to Denmark. These are entries from my journal.

CAUGHT

It was in June 1944 that the group was formed. Actually, it had existed before the war, but now it became illegal, but where appearance was concerned, there was no change. We were six Scouts who had been inseparable from the time we joined the scouting movement, until now that we were all Rover Scouts in the “Danish Scout Corps.”

The members of the group are: Sjus, College student, age 21; Manne, Clerk, 21; Jens, Machinist, 22; Tarp, Photographer, 25; Poul, Teacher, 28; Myself, Apprentice, 19.

Poul was the leader of the group. We trained in the use of weapons and explosives and acted for a time as an intelligence group until Poul had to go underground because the Gestapo wanted him. After that the group became an explosives group with Tarp as its leader.

On the 3rd of November 1944, Tarp was arrested together with Fritz, another scouting friend, who was in another group. The rest of us went to Copenhagen, where we associated ourselves with Holger Danske, the Danish underground.

Jens and Sjus were arrested by the Gestapo on February 2 in Vordingborg, while in action. Meanwhile, Manne and I were waiting in Copenhagen. We phoned the hotel in Vordingborg and were told that they were still staying there. That was the 5th of February, and it was the Gestapo we were talking to, which we did not know.

Manne had gone into town that day to deliver a load of potatoes, and he came home with the truck around 5 o’clock. In the meantime, I had balanced the day’s sales and went out to help him unload the empty sacks from the truck.

While we were doing that, a big Buick drove up on the other side of the street and five plainclothesmen emerged. Because of the noise of the generator, we did not hear them, but Manne had the impression that something was wrong, which he intimated to me, after which he quietly went down the street and around the corner. I was, however, too busy to notice this, so I went into the courtyard with a bunch of sacks.

As I went through the portal to the courtyard, I encountered three men with flashlights. I lifted my cap, said hello, and asked them if they were looking for somebody. “Keep walking,” they answered, and I got a pistol in my back.

They did not have to tell me twice, and I went quietly into the warehouse, where I disposed of the empty sacks while I quickly considered all the possibilities.

The only way out was through the portal, and the three men were still there, while the fourth one was upstairs ringing the bell to the apartment. My only chance was to put all my eggs in one basket and try to bluff them.

I hoisted some empty crates on my shoulder and went through the portal. The three men blocked my way, but I said politely but firmly “bitte,” and I’ll be damned if they didn’t move out of the way.

Once in the street I tossed the crates into the truck and told the driver that the men were Gestapo and to get out of there as soon as I had turned the corner. I then went quietly around the other side of the truck, crossed the street, and disappeared around the corner. That, however, was the end of my composure. My legs were shaking under me as I ran down the street and caught a streetcar to the center of town.

During the evening I managed to get hold of Manne, and we arranged to meet at the Golden Cafe, where we discussed the situation over a snack and a beer. We agreed to contact headquarters and then disappear into the country for a while. No sooner said than done.

I went up to the apartment, where headquarters were located, leaving Manne in the street to stand guard. It was about 10:30 when the elevator stopped at the fifth floor, and when the door opened I stared into the mouth of a pistol while three big “Hipo” (a Danish auxiliary police corps) guys shouted, “Hands up, you big a——.”

I was escorted into the apartment, where everything had been upended––bullet holes in the walls and evidence of a great struggle. We later learned that the apartment had been raided the night before, during which the freedom fighters had shot their way out to the back stairs and escaped with the loss of one man. The rest of them reached Sweden in good shape.

My pockets were emptied with a speed and elegance that indicated that it was professionals I was dealing with. They were elated at finding two packages of Queensland cigarettes. My papers––e.g., false identification and streetcar pass in the name of Vagn Aage Jensen––were examined.

They asked me what I was doing there. “I came to buy a pair of skis, I don’t understand––what is going on?” They were convinced enough to ask me to sit down while they checked this bit of information. I was seated on a sofa with two other “innocents.” No doubt my explanation would never have stood up, but at that point the doorbell rang and my heart jumped into my throat.

While this was going on, Manne had been shadowing “Børge”––the Gestapo man mentioned in the foreword. Børge, however, had been shadowing Manne and, as luck would have it, Børge pulled the gun first and, when the door was opened, Manne entered with his arms raised, followed by Børge, who pointed his gun at me. He asked Manne if he knew me. It was hopeless to deny it, as Børge had seen us together before I entered the apartment building.

This was too much for one of the powerful Hipo guys. “Aha,” he said, “so you are full of lies.” He commanded me to stand up and, at the same time, he hit me in the face with the butt of his revolver and knocked me to the floor. In order to gain time to think, I feigned unconsciousness, or maybe it was to avoid further blows. I was, however, kicked back to life and given a lecture to the effect that, although I wasn’t going to live long, at least I was going to learn to speak the truth before I died.

They now passed around my Queensland, and as I saw my month’s ration go up in smoke I asked to have one too, so at least I could get a chance to share them. After all, it was my treat. Manne gave me a reproachful look, as if to say, “You don’t need to hasten your own end.” He was right. I had hoped to impress them with impudence, but got my ears boxed for my effort.

After that, we got half an hour with our arms raised and were then allowed to sit on a stool while only three Hipos watched over us, machine guns at the ready. The rest of them turned the apartment and attic upside down, in the process of which they found German uniforms, passes, and quite a tidy bunch of weapons. This was all packed in a couple of large suitcases.

It was midnight, and our hosts were hungry. Luckily, I had brought half a loaf of bread and some butter, and after raiding the refrigerator they made bacon and eggs. It was a wonderful smell as they took turns eating. To us they said, “You won’t get anything to eat now, for reasons you will soon find out.”

In the meantime, there arrived from the city jail an Opel Kadet car together with a couple of civil Gestapo, one of whom––a small man with unpleasant, piercing eyes––was said to be the chief from the city jail. Before we could exchange a pleasant “Hello,” he hissed: “Sie lugen jah Mench,” and we were handcuffed; the criminals had been caught.

Manne and I were cuffed together in such a way that we each had a hand free to carry a suitcase.

GESTAPO JAIL

On the way to the city jail, we crossed Raadhuspladsen—Copenhagen’s main square––and at the same time I noted that it was 1:35 am. I wondered if and when I might again walk across Raadhuspladsen as a free man.

Once we arrived at the jail, we were escorted up to an interrogation room by the chief and Børge. The chief sat down expectantly, while Børge began a further examination of our possessions. In my billfold he found kr.250.00, which he promptly transferred to his own.

Unfortunately, Manne carried on him a piece of paper with the description of a “sticker,” whom we were to have shadowed, and I thought that was the reason they asked him to remove his glasses. They moved me into an adjoining room after first having cuffed me, arms behind my back, with a pair of French handcuffs. These handcuffs had the excellent advantages that the more you moved your hands the tighter they got.

From the adjoining room came the frightening noises of the terrible beating Børge was giving to Manne. I managed to gather my thoughts long enough to note a growing hunger, as we had not eaten since early morning. I was fully aware that the intention was for me to be weakened from the sounds of Manne’s groans and Børge’s increasingly heavy blows and bad-tempered shouts. The groans were interspersed with half-choked screams as Børge got even more bestial.

By the light from the keyhole, I could see that the time was 3 am. (I still had my watch.) I started to orient myself a little. Two steps each way was all the room there was. I discovered that there were shelves on the end wall of the room, and as I examined it closer, I found a bottle, which I pulled to the edge of the shelf, after which I turned around, knocked it over with the help of my mouth, bit out the cork, and smelled it ––ahh––it was Calleric Punch. The bottle was half full, and I was empty. In no time at all, we had exchanged roles, and I had a much lighter outlook.

About 11/2 hours later, when things quieted down next door, I was fetched from the darkness. I became instantly sober as I looked around the interrogation room. Manne was gone, but the seat of the easy chair in the middle of the room was covered in blood, and there were pools of blood all over the floor.

Now followed an interrogation which I shall never forget. It lasted three hours, and it was one beating after the other. My face was decorated and my backside beaten to a pulp. Needless to say, it was my countryman Børge who carried out the beatings, and he did it with great care while the Germans merely watched approvingly.

Suddenly Børge stopped and asked me, ”How long have you known the Gisselbæks?”

(The Gisselbæks were my landlords in Charlottenlund.)

“From the day I rented a room from them in December.”

“That’s a lie, that’s a lie, we know it all,” Børge screamed. “How long have you had an affair with Mrs. Gisselbæk?”

“I really haven’t had an affair with Mrs. Gisselbæk,” I shot back, “considering that Mrs. Gisselbæk is 85 years old, and I am not yet 19, it did not occur to me.”

Børge did not answer but continued to massage my face. These gentlemen had no sense of humor, but the accusation was dropped.

The beatings continued, and the more they beat me the more lies I told until, in the end, I couldn’t remember my own lies. Finally Børge knocked me out, and when I came to I mumbled to Børge that it was possible to squeeze a lemon till there was no juice left. The German asked for a translation, and after that the interrogation was over.

It was 7 am; my watch was still ticking in spite of everything. I was now escorted down to the duty room where I had to turn over my pipe and tobacco as well as other unimportant items left over from my stay in the interrogation room. I kept my watch––and nobody noticed.

Then I was handed over to the custody of the police-soldiers and installed in cell 42 on the third floor. This was a so-called “Pipcelle” with no windows, four naked walls, two mattresses, and a chamber pot. A light bulb in the ceiling cast a sharp light both night and day.

I inspected the premises and greeted my cellmate––a young machinist taken in a street raid but actually innocent of any wrongdoing. He had been alone in the cell for four days and was glad to have company again.

I was hungry, and it suited me very well that the food was passed around at this time. We each got a bowl containing a small portion of rotten fish and a piece of raw gherkin. Added to this was a handful of half-rotten unpeeled potatoes. My appetite disappeared immediately, and I consumed only the few edible potatoes, leaving the rest.

My next concern was bed and sleep, but before this I rubbed the brass frame of the door peephole clean and used it as a mirror to inspect my damaged head. A gash in the upper lip, one eye swollen shut, and the whole head puffed up. I threw myself down on one of the mattresses and went quickly to sleep in spite of the light and my aching head.

Next morning around 9 o’clock we got two slices of bread and a mug of coffee––at 10 o’clock I was dispatched back to interrogation again.

The interrogation was conducted in the same way as yesterday’s. The first time my hands were handcuffed behind me; this time they put me in a straightjacket, placed me in a chair, and proceeded to again pound on my previously battered visage.

When they had tired of playing with me, they released me from the straightjacket more dead than alive, and Børge remarked, “Now you will be given a fair chance, you a——!” and sent for a Hipo man of heroic dimensions––a full head taller than me and with a width of shoulders and muscles like a bear.

At that moment I could barely manage to stay upright, and the fight could not be categorized as fierce. One blow dumped me on the floor in the opposite corner, and when I woke up in cell 42 my cellmate was in the process of cleaning my face with water from his drinking mug.

A couple of nondescript days passed by––interrupted by visits to the toilet morning and evening. Friday, two new captives joined us in the cell, a drummer from Peter Kreuder’s orchestra (a deserter from the German Army) and an antisocial individual suffering from gonorrhea.

On Saturday my first cellmate was released; he was so law abiding that he dared not phone a greeting from me to my family. The next day our antisocial element, including his gonorrhea, was transferred to the Danish department.

The atmosphere improved immediately. All that was left was me and the drummer singing Peter Kreuder melodies all day long. He was irrepressible; he believed in Germany’s right to expand but not in a dictatorship accomplishing it. A couple of days later he was executed as a deserter, but he left the cell singing.

The next day new guests arrived. Two prisoners from Neuengamme in Germany; they had originally been incarcerated as so-called anti-socials. Both had been picked up in a street roundup and sent on to Germany because of 15- to 20-year-old criminal records. One of them was feeble-minded and under the protection of the Danish Mental Health Authorities. Both had the ultimate hair cut (no hair), had flea bites all over, and suffered from dysentery. It did not take long to fill the chamber pot, and then the floor had to serve. The stench was unbelievable–– ventilation was nonexistent.

On February 11, Sjus appeared outside my cell door whispering that the Russians had bypassed Berlin and reached a point 26 kilometers farther to the west. I noted it carefully on the wall of my cell and thought: “In two weeks the war is over!” As it turned out, that was not the last time I had that thought.

Finally on Friday, February 16, the “Wachtmeister” yelled “Aage Jørgensen—alles mit nach Vestre!”––the magic shout which, if nothing else, would get me out of the stinking cell where I wandered seven steps back and forth like a lion in a cage. I got dressed in a hurry and arrived in the duty room where Manne already was waiting together with another prisoner.

[After a 12-day trip, Jorgensen entered the Dachau concentration camp outside Munich on March 2, 1945, with other Danes who had been in the resistance movement in Denmark.]

DACHAU

Dachau was known to several of us as one of the worst political concentration camps in Germany––it had been established in 1933.

The snow was being whipped along by strong winds. I was standing up in the [railroad] car––couldn’t sit down, but couldn’t keep standing, either. I was exhausted and cold and feared the worst. In the condition we were in, we might well freeze to death, but we fought on even though there seemed no hope of being let out before morning.

We had collapsed helter skelter on top of each other when the car doors were slid aside. The darkness outside was packed with police soldiers and illuminated by a lonely, faint platform light.

The transport leader yelled in true Prussian fashion, “If anybody tries to escape, you will all be shot immediately.” At that moment the man probably uttered the best joke of his life––we fell off the car more or less like cow plop and none of us were able to run even for 10 steps. We were ordered into formation four by four; at the rear were our sick, three of whom were dying, being carried and supported, while the rest of us took turns with our luggage.

The column started to move along at a slow pace prodded by police soldiers packing machine pistols. We had two kilometers to go to reach the concentration camp, and we practically dragged ourselves along through the snow and the withering cold.

Finally we stood at the gates to “KZ Dachau.” The gate opened up into a big barrack-like building and above it we saw the swastika and the German eagle meticulously crafted in bronze.

We were prodded and kicked through the gate and then counted four by four. If anybody lagged behind, a solid Prussian boot in the behind provided immediate encouragement.

When we had all passed through the gate, the first ranks were facing another gate, and the whole ceremony was repeated. Thus we passed several more gates, and each time we were counted (Germans are a very thorough and methodical people) to eventually pass through a large factory complex and reach the final gate leading into the living quarters compound. This was a little city in itself, at that time housing about 30,000 prisoners.

To get to this gate, one had to cross a perimeter minefield, which bordered a moat and a six-meter-high wall festooned with electrified barbed wire surrounding the entire area. Inside the wall was another 20-meters-wide minefield and then a six-meter-tall, high‑voltage barbed wire fence.

On the inside of this fence “Spanish Riders” [a barbed-wire entanglement installed low to the ground in order to trip potential escapees] had been installed (likewise electrified), and in front of these were a network of zigzag trenches where soldiers could take cover in case of mutiny among the prisoners. It should also be mentioned that tall stone watchtowers were located every 50 meters along the wall. The machine guns in these towers were manned night and day and effectively covered every inch of ground inside the compound. Furthermore, one had to consider that the factory complex totally surrounded the prison compound, so a successful escape from the compound left another five walls to go––with alert, well-armed guards and electrified barbed wire. Under these conditions, escape was doomed to failure.

While waiting in front of this last gate, some of us succumbed to our raging thirst by scooping up some snow to eat––we had had nothing to drink for three days. They were immediately warned that the snow was heavily contaminated with all kinds of bacteria.

Having passed the gate (and the inevitable tally), we trudged down one of the camp streets and entered a barrack used as a reception area for new prisoners. Here we deposited our sick comrades in one end of the room and stretched ourselves on the floor, enjoying the freedom of being able to lie flat again in spite of the cold. In several places the floors were covered with a layer of ill-smelling groundwater and, in spite of all the warnings, some weak souls could not resist drinking it.

Around 3 o’clock, the prisoners in the kitchen reported for duty and soon after a couple of inmates brought us a big keg of warm “coffee” and each a 200-gram hunk of rye bread.

We dug in with a vengeance, but I found to my horror that I simply could not chew the bread. My teeth had loosened so much that I could have plucked them out one by one, and my gums were very sore. I gave Manne half of my bread and crumpled up the remainder sufficiently to swallow without chewing.

Our old Nykøbing acquaintance Kjeld Staunstrup gave me a pair of stockings and a handkerchief. I had started this venture with no luggage at all, and my outfit was really in a sorry state.

I discovered that there were Lagerpolizei [camp police] present in the barrack hall. Only long-term prisoners were eligible for this exalted position. I struck up a conversation with one of them, and he turned out to be a pleasant chap, a young Dutchman who had been in Dachau for eight years. Our conversation was conducted in German, which was the international language of the camp.

He told me that, compared to two years ago, Dachau was now a regular paradise (I found that hard to believe), and he tipped me off on some current state-of-affairs conditions.

If one avoided falling ill, a normal human being could expect to survive only four months on the food allotments provided––unless, of course, the individual had been assigned a job in the kitchen, in the Lagerpolizei, or similar job allowing the scrounging of a bit more food on the side.

He also told me that the camp contained a bordello staffed with young Polish women––prisoners forced into degrading themselves. They were sterilized and, in most cases, were young girls from respectable Polish families. The bordello was reserved for Blockältester [the “elders” who were assigned to be in charge of each barrack] and similar gentlemen, a situation that did not worry me unduly.

Then he outlined the coming events. For the first three weeks we would be located in a quarantine barrack; if we managed that without getting ill, we would be moved to the regular barracks (by the way, a preponderance of the barracks were classified as either quarantine or hospital barracks) and start working in a factory or something similar from seven in the morning to seven in the evening, with 15 minutes for a dinner break.

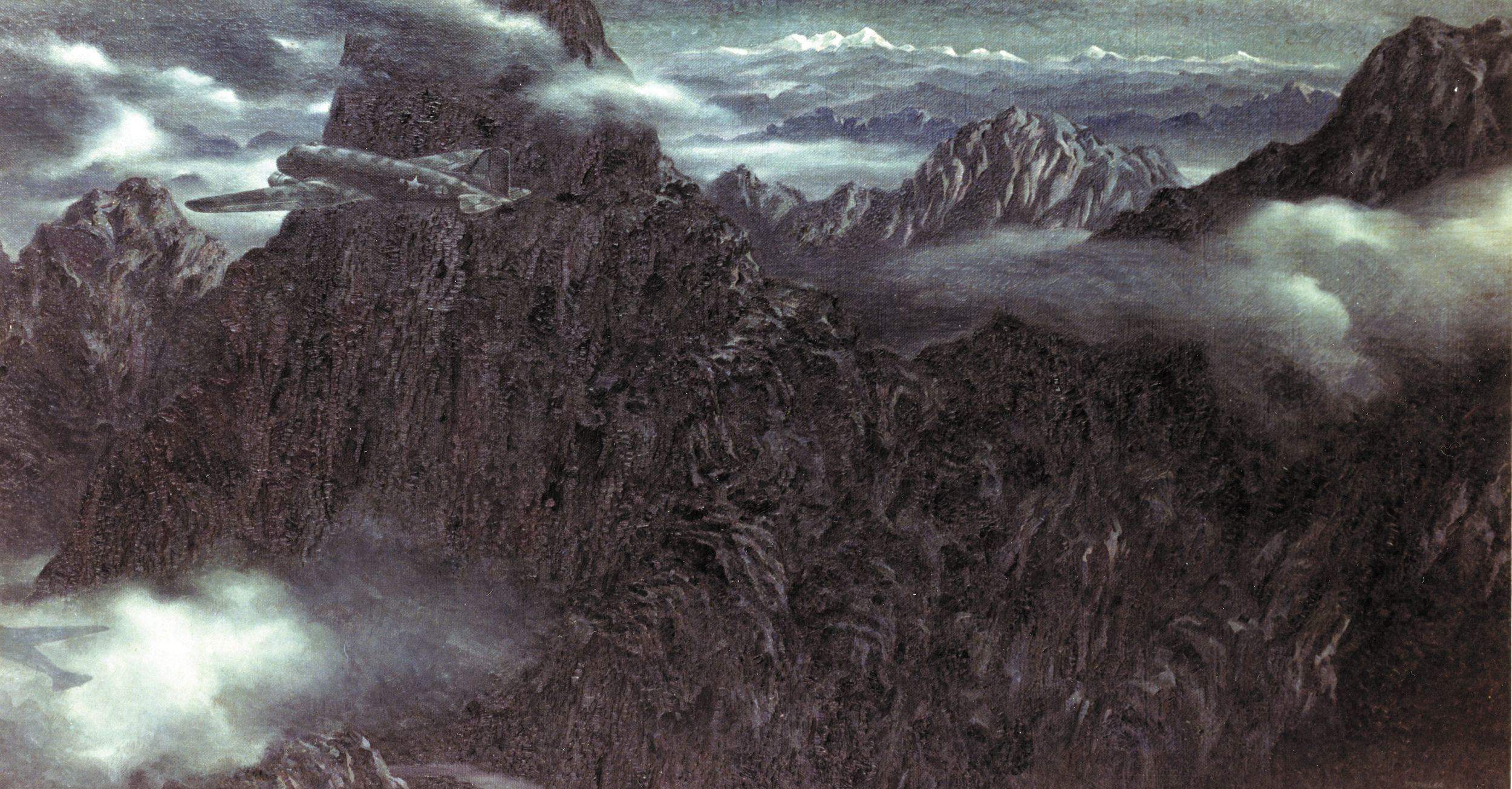

Among the factories there was one that produced spare parts for aircraft; most of the factories were engaged in the armaments end of things. During the quarantine period I could expect some coffee in the morning, a bowl of soup at noon, and some coffee and 200 grams of rye bread in the evening. Afterward, when working, the ration was increased to 350 grams of bread per day and a little more soup.

After all these explanations, he requested some tobacco, but I had to disappoint him with my story of the tobacco having run out a full week ago and that our last smoking venture consisted of 25 people sharing a pipe stuffed with the burnt-out remnants from all the pipes available.

By the way, he did supply a few tips regarding the work. It was paying work with remuneration in so-called Lagerpfennig to the tune of 1 to 4 pfennig per week depending on the nature of the work. One could purchase additional soup, some sour marmalade, and some 15 percent soap in the canteen (yes, they had one of those, too). I never did manage to experience all these wonders, seeing that I spent all my time in the camp under quarantine.

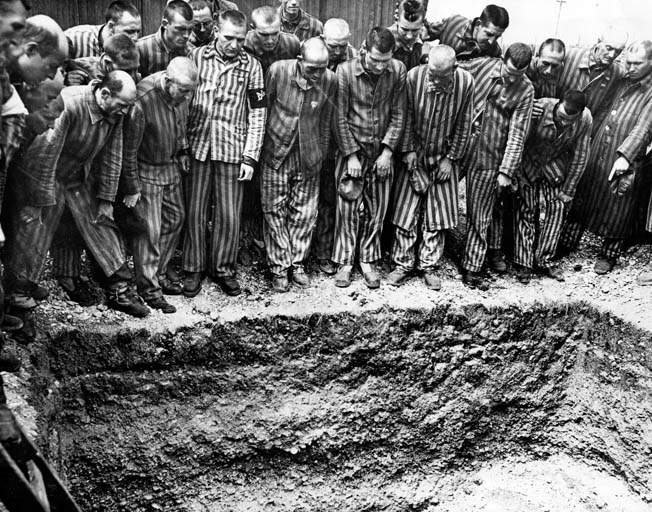

Dawn had arrived, and we noticed an L-shaped building across from us. The part of the building closest to us housed the combined communal bathing room and gas chamber; the other branch was the camp kitchen. Painted on the roof of the building in large letters was the message: “The only route to freedom is death.”

At 6 o’clock we observed a platoon of prisoners in their striped uniforms being marched in, and we got the first whiff of what was in store. Never had I seen such a group of emaciated, miserable beings. They hobbled along coughing and with their breath rattling in their throats. We had a couple of degrees of frost, and they were dressed in their thin prison uniforms. Many were barefooted, and the lucky ones wore open bath sandals. There were 10- to 11-year-old boys and oldsters in their 70s and 80s among them.

Our own senior [barracks elder] was 65 years old––Olsen, a retired mechanic from Odense––and we almost had to carry him on our hands to get him through all this alive. He had been taken as a hostage because they could not get hold of his son-in-law.

The prisoners were marched into the gas-cum-bath chamber through a door in one end of the building; inside, while passing an open window, they tossed their clothes out the window in a heap on the ground––we never saw them again.

At that moment, while we were in a mood of bleak despair, somebody shouted “Achtung!” By now we had a pretty good idea of the meaning of that particular phrase and tried to stand at attention as well as we could.

NEUENGAMME

[In March 1945, all Danish and Norwegian concentration camp inmates were sent to Neuengamme outside Hamburg in northern Germany; the prisoners were informed that they would soon be released to the Swedish Red Cross. This was a concession from SS leader Heinrich Himmler as part of a bargain with Count Folke Bernadotte, vice president of the Swedish Red Cross; Himmler was trying to save his own hide by performing this humanitarian deed.]

We marched past a huge roof-tile factory where the camp prisoners worked and then past some pretty barracks fronted with beds of flowers––“Not bad,” we thought––but these barracks were for the soldiers, and we just shuffled on.

Finally, we turned in through a wrought-iron gate flanked by low barrack buildings, were counted four at a time, and were now standing in the Neuengamme muster yard.

We took it easy, sat down on our parcels, and munched on some crackers and jam, and then “Jacob” arrived. Jacob was a young Dane with the common name of Erik Jacobsen—he had been elected spokesman for all Danes imprisoned in Neuengamme.

He greeted us and held a little speech describing all the activities that were on the forbidden list (it was a long list), and he ended with saying that the only way we could gain respect would be to ignore all rules––this was not advice but a request. He made a good impression, and we decided to honor his request; we were still in a sanguine mood, having been under the protection of the Swedes.

An SS man conducted the muster, and a command was given: “Fremad march,” and we were on our way to our new quarters: Block 18 in Neuengamme.

Block 18 was, if possible, even more sinister looking than Block 19 in Dachau. By nailing some boards together, an array of “sand boxes” had been built on the floor––no sand, of course, and with gangways between them.

Manne and I, plus 28 others, were assigned a box measuring three by five meters. The floor was covered with straw, and each man was given a blanket. In spite of the crowding, it was still preferable to Dachau––better headroom and air circulation and better opportunity for social contacts.

The block was one big room with a washroom attached to the rear, and behind that a room with a row of toilets. Both facilities could accommodate 10 men at a time––and of course there were “only” 300 of us in all.

The camp gallows was located in the block street, and its steps had been worn hollow by the multitude that had ascended them.

The Norwegians were housed in Block 19 on the other side of the street, farther up on the same street. Restricted by an additional barbed-wire fence lived the so-called antisocials (among them the son of police inspector Mellerup), as well as all prisoners who had been caught trying to escape. These prisoners wore red marks front and back targeting the heart; if they moved beyond established boundaries the guards had orders to shoot them on the spot.

Every Sunday three of them were executed by hanging; the day before our arrival had been a Sunday complete with its traditional executions. These executions were a ritual part of the Sunday festivities. Around noon the camp orchestra started off by playing martial marches, and at the conclusion of one of these the victims were hanged; then followed another inspirational piece of music.

[The camp orchestra consisted of about 30 prisoners, who were fed a little better than the remainder. They played every morning when the prisoners went to work and every evening when they returned. The day the Americans crossed the Rhine, they played “Wacht am Rhein.”]

After the hangings, the centerpiece (the gallows) was moved off stage to its resting place in the street, and they played football. All this happened in the mustering yard with all prisoners present and accounted for.

Like Dachau, we had to be kept in quarantine and could not leave the block street. Conditions for the sick were equally as bad as in Dachau, and in our barrack we had already many who had fallen ill. I had to lie down with an enflamed throat and was placed with other patients lying in a row against one of the sidewalls.

When we arrived the block was unbelievably dirty, but, helped by our Red Cross cigarette supply, we started a major renovation effort. We got the room disinfected and painted all over, and it became almost livable.

To begin with, we had to contend with German Blockälteste and Kapos [privileged prisoners who were appointed by the SS to administer corporal punishment and keep order in the barracks], but we managed to negotiate a deal permitting us to select these worthies from our own ranks. Pastor Madsen was elected as our Blockälteste by democratic means.

We were happy to find the flea and lice population to be much smaller than in Dachau, but we continued our daily attempts to hunt down the lice. We had escaped the typhoid epidemic in Dachau, but we had brought some carriers with us and the disease started to spread again, with people dying every day from this dreadful disease.

One day at 4 am we mustered in the block street with our few possessions, and the usual came to pass: we waited. The first event happened at 8 o’clock when the Swedes arrived with all their rolling stock and drove off with the sick and the old.

At the same time we were told the British were barely two kilometers away and that they had given the camp a deadline for its evacuation of 8 that evening. From 8 o’clock on, anything could happen. The Germans had placed artillery two kilometers away on the other side of the camp, thus placing us directly in the firing zone between the two front lines.

We were also put on notice that more transportation would arrive from Denmark but that there would not be room for all of us.

Around noon some white Danish buses arrived. In Denmark the buses had been taken off their regular runs, received a coat of whitewash, and been dispatched––all within 24 hours.

To avoid panic in securing seats on the buses, we needed a departure schedule and tried to find our trustees so one could be drawn up. None could be found; believe it or not, all these worthy individuals had departed on the first bus.

We managed to agree on a plan in a hurry, and all we young ones were left to be the last out.

Manne and I walked around weighing our options. We seriously considered hiding in a basement until the expected fighting had rolled past the camp area, a time span of, at most, 24 hours. We figured that we might prefer returning to Denmark via France and England rather than now, while “the green ones” [the Germans] still ruled the roost.

One of buses had brought an official from the Danish Foreign Service, Frans Hvass. He supervised the transport operation, saw to it that everybody got a seat, and did not leave Neuengamme until the last Dane and Norwegian had been taken care of.

With our departure postponed, Manne and I made a small fire in the middle of the street to fry some bacon, which we ate together with a couple of hunks of rye bread. We relaxed and waited for the moment when our bald heads again were to travel and see a little more of the world.

Throughout the afternoon buses continued to arrive, but Manne and I did not board them. Finally, at 8:05 pm, we left the camp on the last bus. Two hours later Neuengamme was in the hands of the Allied forces.

As we passed through the idyllic little village of Neuengamme in a Danish bus, with a Danish bus driver at the wheel, it suddenly occurred to me that this was April 20––the birthday of Hitler––and that we were on our way back to Denmark, and that our return offered a reasonable assurance that it would be Hitler’s last birthday.

It was already dark, and we drove only about 15 kilometers to reach a Swedish-owned property, Friedrichsruhe, where we spent the night in the woods under a clear sky. The Allies could not guarantee the safety of the transport during the night; therefore, we drove only during daylight.

Next morning we proceeded via Lübeck and Neumünster, seeing that Hamburg was in the process of being occupied by the British Army.

This trip gave us a good idea of how much the civilian population had suffered. They were ill‑clad and undernourished, and everywhere were children begging for scraps of food. Even those who had suffered the most under the German regime were reluctantly handing out food to the children. The children were not responsible for the war––but probably suffered more then anybody else.

In passing through a little village, we noticed everybody busy collecting flyers (air-dropped propaganda leaflets) and burning them in a forge. Believing that these leaflets were British, I managed to obtain one (I still have it). Actually they were a last desperate exhortation to the German people to resist the enemy, and they were being burnt in the village forge. Obviously there was no mood for further resistance. The content of the leaflets was typical of German Nazi propaganda; it will suffice to quote the fat headline “Kampf oder Sibirien! Standhaftigkeit oder Tod!” (“Fight––or Siberia! Steadfastness or death!”)

FREEDOM

Knowledge of the German capitulation arrived the evening of May 4, and we all wanted to get back home immediately, but that did not happen. On May 17, we finally returned and when we landed in Copenhagen the authorities provided us with money and ration coupons, enough to allow us to reach our homes without further assistance.

Aboard the ferry we said our goodbyes and wished each other good luck. I also met several other comrades who had obtained sanctuary in other parts of Sweden. Among them was a tram driver almost totally enclosed in bandages.

He told me that his bus from Neuengamme had been delayed to such an extent that they had had to risk driving at night to get away from the front line. Their bus had come under machine-gun fire and had burst into flames. They had all jumped straight out through the windows and only had two casualties, but the survivors had all been wounded by a combination of machine‑gun bullets and glass splinters. He had received a bullet in the back but was on the road to recovery.

I said a special goodbye to the “old” man, Olsen from Odense. He had survived in spite of his age and his affliction (erysipelas).

That was May 17. A week later I was back in the civilian life. My hair grew back, slowly but surely, and I was back to being my old self. Later, I visited several of the old comrades but only a few had recovered from our ordeal as well as I had. In too many cases there had been nervous breakdowns, serious cases of tuberculosis, etc., etc.

Well, we have peace again, and Denmark is a free land, so what is the preferred topic of discussion?

Reconstruction––no way, rather the next war! I wonder if the nations of the earth can keep the peace until such time that they can unite and declare war on the moon. I do not believe so, but this war has certainly not converted me to a militarist. If only it has had the same effect on the other survivors, one would assume that we are a step closer to a lasting peace.

But peace is, and will probably remain, as the interval between two wars. But at the moment we do have peace, and every hour of the day one should appreciate that fact. [Peace is] the most valuable thing we possess––and something that at any time can be lost again. (Written in Copenhagen, 1945.)

Today Børge was arrested!

For 11/2 years he has been hiding in a room rented from an elderly lady, who was not suspicious in spite of the fact that Børge, in all that time, never went out in the daytime, but let her do all his shopping for him.

But NOW he has been arrested––and only now is the war really over for my five friends and myself. Børge is in the City Jail––the same place where he tortured many people, including us. “Your time is up––and now you better answer OUR questions,” said the police sergeant, when Manne was at the city jail to identify him.

Postscript

After the war, Jorgensen’s torturer, Børge Bendahl, was sentenced to death. On June 28, 1951, the sentence was commuted to life in prison. (Bendahl served only seven years and was released in 1958; he then moved to Sweden.)

After returning to Copenhagen and finishing his apprenticeship, Peter Jorgensen attended school in London, returned again to Copenhagen, got married to his girlfriend Mette, had children, then in 1953 took a position in Montreal, Canada. On December 19, 1960, Jorgensen received kr. 874 ($126 Canadian) from the government of Germanyin compensation for his experiences. He started a company called Scandan, which sells Danish products and of which he is still the president while day-to-day operations are run by his son Steen. Peter, age 89, and Mette live in St. Lambert, Quebec.

Awesome reading, thanks to people like Peter who did more than most to bring peace.